Abstract

This study investigates the spatial and temporal variation of intertidal macroalgae along the eastern coasts of Qeshm Island, Persian Gulf, Iran. Monthly sampling of abundance, biomass, richness and diversity of macroalgae at three intertidal levels was carried out at two different sites during 1 year. The samples were collected every month using quadrats (0.5 × 0.5 m) from October 2012 to September 2013. The species dry weight was applied to examine changes in biomass and assemblage composition of intertidal macroalgae using univariate and multivariate analyses. A total of 42 seaweed species (10 Chlorophyta, 9 Phaeophyceae, and 23 Rhodophyta) were identified. The results confirmed a temporal pattern in the growth of the algal species which also showed a biomass zonation pattern from upper to lower intertidal. The annual mean biomass of macroalgae was highest in winter (29.3 ± 9.8 g dry wt m−2) and the lowest in autumn (17.3 ± 13.5 g dry wt m−2). The annual dominant species by biomass was Padina sp. followed by Padina australis. The most common species in the area, during the sampling period include Ulva intestinalis, Ulva lactuca, Palisada perforata and Padina sp. According to the similarity percentages analysis (SIMPER), the species Ulva intestinalis, Dictyosphaeria cavernosa (Chlorophyta), Padina australis (Phaeophyceae), Champia spp., Centroceras clavulatum and Palisada perforata (Rhodophyta) were responsible for the most dissimilarity of species composition between four seasons during the sampling period. BIOENV analysis indicated that the main environmental factors structuring macroalgal community at the study area were TDS and pH. The simple macroalgae community on the eastern coast of Qeshm Island and absence of slow-growing perennial macroalgae, such as members of the Sargassaceae, known from the lower shore at other intertidal localities along the island’s coast might relate to the predominantly unsuitable sandy-stony substrates unsuitable for their colonization and the unfavourable impact upon them of urbanization.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

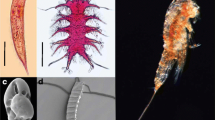

Marine macroalgae, also known as seaweeds, are the macrobenthic forms of marine algae that are found from intertidal to shallow subtidal zones. These macro-autotrophs include three major divisions: Chlorophyta (green algae), Ochrophyta, class Phaeophyceae (brown algae), and Rhodophyta (red algae) (Koch et al. 2013). Seaweeds along with seagrasses are part of the base of the food web in marine coastal ecosystems with a vital role in nutrient cycling processes. They also support the diverse assemblages of associated species by providing them a physical structure (Koch et al. 2013; Leopardas et al. 2014). Therefore, any changes in patterns of such habitat-forming species may create bottom-up changes in the food web and influence the associated fauna and flora (Bates and DeWreede 2007).

The Seasonal variation in rainfall, salinity, nutrients and light intensity could result in a kind of succession in the intertidal macroalgae. Consequently, the structure and composition of macroalgae assemblages fluctuate both in time and space in response to the extreme conditions in the Persian Gulf (Chapman and Underwood 1998; Sangil et al. 2011; John 2012). Understanding changes in their communities by detection and monitoring of local species, their distribution, and their availability is an indispensable part of a long term preservation and management of biodiversity in coastal waters (Trono 2003; Raffo et al. 2014). Additionally, it may lead to predict the ecological responses to environmental changes such as pollution and climate change that are mainly expressed as changes in species distribution, abundance, and diversity.

To date, few papers have published on the dynamics of macroalgae communities in coastal waters of the Persian Gulf and the Gulf of Oman. The previous studies have focused on the biomass variation and diversity of seaweeds among seasons, whereas the species composition in different seasons and the role of specific macroalgae in the variation of community were neglected. The only previous quantitative study on variation in biomass and seaweed diversity using univariate analysis was undertaken by Dadolahi-Sohrab et al. (2012). The purpose of this study, therefore, was to provide the first comprehensive quantitative investigation of vertical and seasonal changes in the composition and structure of macroalgae at a local scale with regard to community structure and composition. This study has three key objectives: (1) to determine temporal changes in composition and diversity of macroalgal assemblages and its relation to the environmental variables in the intertidal zone of two gently sloping shores; (2) to describe the zonation patterns of three groups of seaweeds in the study area (3) and; to identify the dominant species of every season in the study area.

Methods

Field study site

This study was carried out in the intertidal zone of the eastern coasts of Qeshm Island (an urbanized area) from October 2012 to September 2013. Qeshm is the largest island of the Iranian side of the Persian Gulf with an area of 1491 km2 (Aghajan Pour et al. 2013). Two locations were selected on the eastern coasts of the island: Zeitun Park (site 1) (26 ° 55' N, 56 ° 16' E) with a sandy-rocky substrate and Botanical Garden (site 2) (26 ° 58' N, 56 ° 15' E) with a sandy- stony substrate (Fig. 1). The intertidal zone of these areas was between 100 and 150 m wide with \slopes between 1 and 2° and the same tidal amplitude of semi-diurnal tides (0.12–3.37 m). The temperature, turbidity, salinity, TDS (total dissolved solid) and pH of surface water was measured every month during the year of sampling. In the sampling area, the temperature varied between 25 and 33 °C and salinity ranged between 42.3 and 43.7 ppt. during the temperate and warm seasons, respectively.

Sampling design

At each site, three line transects perpendicular to the waterline, were placed randomly to investigate vertical distribution of macroalgae. Three intertidal levels were sampled (high, middle and low) along each transect (including tidal pools) in which three quadrats (50 × 50 cm) were used systematically at each level to compare the changes on the algae community structure throughout the year. The sampling collection was performed monthly from October 2012 to September 2013. All macroalgae within each quadrat (total replicates = 324 quadrat for each site during the year) were removed, bagged, labeled by location and transported to the laboratory immediately. Voucher specimens of the collected algae were preserved in 3 % seawater-formaldehyde and left in darkness for identification. The different species of macroalgae within each quadrat were dried separately in an oven at 60 °C for 24 h., and weighed to the nearest 0.01 g using an analytical balance (Sartorius AG Germany LA120S). Macroalgae abundance was obtained as dry biomass (g) of each macroalgae species. Identification was done using the taxonomic keys and local checklists (De Clerck and Coppejans 1996; Sohrabipour and Rabiei 1999; Sohrabipour and Rabiei 2007; Sohrabipour et al. 2004; Trono 2003; Jha et al. 2009; Braune 2011) to the lowest possible taxonomic level. The names of species and their classifications were validated with AlgaeBase and updated when necessary. Finally, voucher specimens were deposited in Marine Herbarium of Hormozgan University, Bandar Abbas, Iran.

Statistical analyses

Species richness (S), Shannon-Wiener diversity (H′) and Pielou’s evenness (J′) (Jørgensen et al. 2005), for each season were calculated, using the PRIMER-5 (Plymouth Routines in Multivariate Ecological Research) statistical package (Clarke and Warwick 2001). ANOVA tests were then used to determine whether the diversity indices differed significantly between seasons (p < 0.05), pairwise comparisons were conducted with HSD Tukey post hoc test using SPSS 22. Spatial and temporal patterns in assemblage structure of macroalgae were visualized by cluster analyses based on Bray-Curtis similarity matrix applying the fourth root transformation of mean dry weight (g) of each species. Differences in macroalgae assemblages among seasons (spring, summer, autumn, winter) were examined by a one way ANOSIM test (in PRIMER-5) at a significance level of 5 % (p < 0.05). When differences were noticed among a season-group, the similarity percentages analysis (SIMPER) was performed to determine the taxa having the greatest contribution to the dissimilarity between each pair of seasons. This was used to distinguish the main macroalgae responsible for between-group dissimilarity. The relationship between the environmental variables and the macroalgal assemblage was assessed using the BIOENV analysis (PRIMER-5) which compares a biological similarity matrix with abiotic similarity matrices (Clarke and Warwick 2001).

Results

Distributional patterns and composition of seaweed assemblages

In the present study a total of 42 macroalgae taxa (10 Chlorophyta, 9 Ochrophyta, class Phaeophyceae, and 23 Rhodophyta) belonging to 18 families were identified across the three intertidal levels in four seasons and two localities (Table 1). Most of the specimens were determined to the species level. Dictyotaceae (brown algae) with six species was the most common family in the area followed by Rhodomelaceae and Cystocloniaceae with five species (red algae). Among the green algae Ulvaceae was the most abundant family in the area. In most seasons the most common species was Palisada perforata (Rhodophyta in site 1, and Ulva lactuca and Ulva intestinalis (Chlorophyta) in site 2. Different species of Padina were found in most seasons at both sites. The annual dominant species by biomass was an unidentified Padina (Padina sp.) followed by Padina australis. The low intertidal zone had the highest number of species whereas the high intertidal level showed the least number of species. All taxa were confined to one of the three defined zones except Ulva lactuca and U. intestinalis which dominated in each of the zones.

Variation of biomass

The highest and lowest mean total biomass of macroalgae in the study area was observed in winter (29.3 ± 9.8 g dry wt m−2) and autumn (17.3 ± 13.5) respectively. The highest mean total biomass was recorded in the low intertidal level in all seasons except autumn, when low intertidal and mid intertidal zones had almost the same biomass (Fig. 2).

The mean maximum biomass of green algae (17.76 g dry wt m−2) was recorded in winter and the minimum value (0.63) in summer. Whereas, the highest mean total biomass of brown algae (23.8) was observed in summer and the lowest value in spring. Red algae showed a maximum mean biomass of 2.11 g dry wt m−2 in spring and almost the same value (~1 g dry wt m−2) in other seasons. Furthermore, in comparison with red and brown algae, the mean total biomass of green algae in site 2 was considerably more than site 1 in all seasons except summer (Fig. 2).

Diversity indices

In both sites the highest value of the Shannon-Wiener diversity (H') was observed in spring, and the lowest value of richness was recorded in autumn. However, they showed a different seasonal pattern in the biomass, species richness and diversity. Macroalgae abundance and richness showed no significant differences among seasons at both sites, whereas in site 1, diversity was significantly higher in spring than in other seasons (p < 0.05). In contrast, a similar seasonal diversity (H') pattern was observed in site 2, with no significant differences (p > 0.05) (Fig. 3).

Spatial and temporal variation of seaweeds

Chlorophyta

In general, the highest mean total biomass of green algae was observed in the low intertidal level (Fig. 2). The cluster analysis for spatial variation confirmed the two tightly clustered groups which separated at a 77 % similarity threshold. This suggests that the three zones are not significantly different in distribution of green algae (Fig. 4).

Samples from winter-spring (group I) also clustered apart from autumn-summer (group II) at an 11 % similarity threshold, suggesting a significant difference between two season-group (Fig. 5).

ANOSIM test results also indicated difference between the communities of each pair of seasons: autumn-summer, spring-summer (Table 2). The SIMPER analysis indicated that the fluctuation in biomass of Ulva intestinalis and Dictyosphaeria cavernosa were relevant for this separation, respectively (Table 3). The results also outlined that Ulva intestinalis dominated the species assemblage structure in both autumn and winter whereas Ulva lactuca (6.1 ± 1.4 g dry wt m−2) dominated in spring. The mean biomass of green algae was almost zero in summer.

Ochrophyta (class Phaeophyceae)

During the study period the highest mean total biomass of brown algae was observed in the low intertidal level except in autumn site 2 in which the biomass expanded to mid intertidal (Fig. 2). The cluster analysis indicated that brown algae are not strongly clustered by zone, although they formed two groups based on similarities in their assemblage structure (Fig. 4).

In the case of seasonal variation, spring separated from other seasons and a subgroup characterized putting autumn and winter in a single group with nearly 84 % similarities in assemblage structure (Fig. 5).

Results of One-Way ANOSIM showed that brown algae assemblages in autumn were different from that of summer (Table 2). According to the SIMPER analysis the species’ seasonal differences were attributed to fluctuating biomass of Padina australis (Table 3). Furthermore, Colpomenia sinuosa (9 ± 3.8 g dry wt m−2) was the dominant species in the assemblage structure of Phaeophyceae in winter and Padina sp. dominated in other seasons.

Rhodophyta

The result of cluster analysis of red algae differed from that of green and brown algae in that the former showed the high intertidal level as a single group, while the latter indicated the low intertidal as a single group. The level of separation (20 % similarity) was also considerable in comparison with two other groups of seaweeds. This suggests that the low intertidal and mid intertidal levels have more similarity in assemblage structure of Rhodophyta (Fig. 4).

High similarity between seasons was found (67–86 %) (Fig. 5), denoting a low heterogeneity within assemblage structure of Rhodophyta during the sampling period. ANOSIM test results indicated differences between season-groups: autumn-spring, winter-summer and spring-summer (Table 2). As revealed by SIMPER analysis, Champia spp.,Centroceras clavulatum and Palisada perforata were the species with higher contribution to the dissimilarity between these groups, respectively (Table 3). Additionally, Champia spp. (0.5 ± 0.3 g dry wt m−2), Centroceras clavulatum (0.32 ± 0.02 g dry wt m−2), Laurencia spp. (0.75 ± 0.43 g dry wt m−2), and Palisada perforata (1 ± 0.2 g dry wt m−2) were the dominant species in autumn, winter, spring and summer sequentially.

Relationships between macroalgal assemblage and environmental variables BIOENV

The results of the BIOENV analysis revealed that in the study area the most important variables (among the five measured factors) structuring macroalgal communities were: TDS (0.83) and pH (0.79) (Table 4).

Discussion

The influence of time and space on ecological patterns is a major challenge in marine community ecology (Hewitt et al. 2007; Smale et al. 2010). This study provides the first assessment of macroalgae assemblages in Qeshm Island, Persian Gulf, with a quantification of diversity among different months.

Our results were in agreement with other ecological studies, where assemblage composition of macroalgae significantly differed among seasons (Raffo et al. 2014). These patterns are commonly related to the fluctuation of many ecological factors (Williams et al. 2013).

In this study, the highest diversity was recorded for Rhodophyta, which is characteristically diverse and abundant in the macroalgae flora of Iran (Kokabi and Yousefzadi 2015). However, the mean total biomass of red algae was dramatically lower than those of green and brown algae. This refers to the small filamentous morphology of most Rhodophyta species in the study area.

In spite of the obvious differences in biomass (N), richness (S) and diversity index (H′) among seasons at both sites, these changes were only significant for H′ at site 1 (Fig. 3). This resut is not unexpected and has been previously documented (Thongroy et al. 2007; Raffo et al. 2014). Moreover, the values of the Shannon-Wiener diversity index (H') obtained in this study (between 1.11 and 1.95) were considerably lower than those of Dadolahi-Sohrab et al., (2012) reported from the northern coasts of Persian Gulf in Bushehr province (between 2.28 and 2.87). Both urbanization and substratum can cause such a low diversity in the eastern coast of Qeshm Island. Few studies have addressed how physical and biological factors factors influence seaweed community dynamics in the Persian Gulf. However, the result of studies from other parts of the world revealed that abiotic factors such as substratum, nutrients, water motion, sedimentation, pollution and herbivores affect the structure and distribution of algal communities at a local scale (Dıez et al. 2003).

The macroalgal growth and biomass are directly controlled by nutrient availability in most temperate coastal waters (Pedersen et al. 2010; Martínez et al. 2012). In temperate coastal waters, nitrogen and phosphorus concentrations of seawater are high in winter and low in summer (Martínez et al. 2012). Furthermore, Hassanzadeh et al., (2011) reported that seawater is well mixed during winter in the Persian Gulf. Hence, the result of this study which showed the highest biomass of macroalgae in winter may be attributable to increased nutrient availability in this season. Dadolahi-Sohrab et al., (2012) also demonstrated that the period of maximum algal growth is late winter to mid-summer along the northern coasts of the Persian Gulf. In our study, the BIOENV analysis indicated chemical parameters (TDS and pH) as significantly influencing the macroalgal communities along the easthern cost of Qeshm Island.

As is evident in many studies, seaweeds have developed different strategies to cope with nutrient seasonal limitation. For example slow-growing perennials have low uptake rates of nutrient. These species accumulate large nutrient pools in winter, which support their growth in spring ⁄summer when light levels increase. Opportunistic algal forms, however, are fast-growing species which exhibit a high capacity for nutrient uptake to profit from conditions of nutrient enrichment. The high rate of nutrient uptake in this group drives their dominance in localities or seasons of high nutrient and light availability. Since these species do not develop significant storage pools, they become rapidly limited when the supply diminishes (Martínez et al. 2012; Vaz-Pinto et al. 2014). This can explain the dominance of Ulva species in this study during winter which led to the highest total biomass of green algae in this season along the eastern coast of Qeshm Island. Ulva species are among the fast-growing algae (Phillips and Hurd 2003) and showed differences over time, being abundant in winter and early spring then vanishing in summer, which may be attributable to the seasonal fluctuation of nutrient supplies in seawater in the study area.

Our results revealed that Padina spp. was the most important component of the macroalgae community among Phaeophyceae, in the study area. This species formed dense patches in mid-summer and gradually decreased in late autumn; but, never disappeared during the year from the study area. Padina reproduction occurs throughout the year which drives high recruitment rates for this species (Thongroy et al. 2007; Kim 2012). However, the strategies of annual seaweeds that develop during late spring to summer in periods of low nutrient supplies, are poorly investigated (Vaz-Pinto et al. 2014).

Among red algae (Rhodophyta) Centroceras clavulatum and Palisada perforata played an important role in changing the community composition. Palisada perforata which was scarce in site 1 is characteristic of oligotrophic waters (Moreira et al. 2006). Centroceras clavulatum (Ceramiaceae), on the other hand, is an annual alga resistant to the pollution (Dıez et al. 2003). Moreover, Caulerpa spp. and Ulva spp. (Chlorophyta) showed a higher contribution than other Chlorophyta to the dissimilarity among seasons. Although experimental studies are needed for a better interpretation, presence of the opportunistic seaweeds Ulva spp. along with Hypnea musciformis, Hypnea spinella, Acanthophora spicifera, Centroceras clavulatum and Gracilaria spp. in the macroalgae community of site 2 is indicative of a degraded state, which is characterized by nutrient enrichment, heavy metals and turbid conditions elsewhere in the world (Moreira et al. 2006; Orlando-Bonaca et al. 2008; Cox and Foster 2013)

In terms of vertical distribution, the lower intertidal level showed the highest abundance of macroalgae as it was reported by other studies (Scrosati and Heaven 2007; Kang and Kim 2012; Raffo et al. 2014). On a local scale the upward distribution of organisms is mainly limited by desiccation in the intertidal zones (Nybakken 1993; Ingo´ lfsson 2005). It appears the red algae are more usually confined to a single zone than the green and brown algae, usually limited to the lowermost zone sampled at the two sites and only poorly represented at the mid-tide level.

However, green and brown algae showed more homogeneity between three intertidal levels (Fig. 4). The differences of photosynthetic pigments of the three main groups of algae and their tolerance to desiccation may be important in coping with variation of light intensity and hence influencing their vertical distribution in the intertidal zone (Nybakken 1993).

Compared with other parts of the Qeshm Island, the macroalgae community on the eastern coast is very simple due to the absence of slow-growing perennial macroalgae such as Sargassaceae which have been reported from other localities in the Qeshm Island (Sohrabipour and Rabiei 1999; Fatemi et al. 2012). This could be related to the predominance of sandy-stony substrate and urbanization at our study area, in contrast to the other parts of the Island.

This study was an initial step toward understanding the seaweed community dynamics in the Persian Gulf as a sub-region of the Indian Ocean. Therefore, future research is required on the environmental factors such as nutrients affecting seaweed communities on different coastlines of this area to enhance our knowledge of ecosystem functioning and help to predict the ecological responses to environmental changes, both natural and anthropogenic. This study is a useful baseline that can be built on in future studies.

References

Aghajan Pour F, Shokri MR, Abtahi B. Visitor impact on rocky shore communities of Qeshm Island, the Persian Gulf, Iran. Environ Monit Assess. 2013;185:1859–71.

Bates CR, DeWreede RE. Do changes in seaweed biodiversity influence associated invertebrate epifauna? J Exp Mar Biol Ecol. 2007;344:206–14.

Braune W. Seaweeds a colour guide to common benthic green, brown and red algae of the world's oceans. Germany: Gantner verlag, A.R.G., KÖnigstein, K.G; 2011.

Chapman MG, Underwood AJ. Inconsistency and variation in the development of rocky intertidal algal assemblages. J Exp Mar Biol Ecol. 1998;224:265–89.

Clarke KR, Warwick RM. Change in Marine Communities: an approach to statistical analysis and interpretation. United Kingdom: Primer-E, Plymouth; 2001.

Cox TE, Foster MS. The effects of storm-drains with periodic flows on intertidal algal assemblages in ‘Ewa Beach (O‘ahu), Hawai‘i. Mar Pollut Bull. 2013;70:162–70.

Dadolahi-Sohrab A, Garavand-Karimi M, Riahi H, Pashazanoosi H. Seasonal variations in biomass and species composition of seaweeds along the northern coasts of Persian Gulf (Bushehr Province). J Earth Syst Sci. 2012;121:241–50.

De Clerck O, Coppejans E. Marine algae of the Jubail Marine Wildlife Sanctuary, Saudi Arabia. In: Krupp F, Abuzinada AH, Nader IA, editors. A marine wildlife sanctuary for the Arabian Gulf: environmental research and conservation following the 1991 Gulf War Oil Spill. Frankfurt: NCWCD, Riyadh and Senckenberg Research Institute; 1996. pp. 199–289.

Dıez I, Santolaria A, Gorostiaga J. The relationship of environmental factors to the structure and distribution of subtidal seaweed vegetation of the western Basque coast (N Spain). Estuar Coast Shelf Sci. 2003;56:1041–54.

Fatemi S, Ghavam MP, Rafiee F, Taheri MS. The study of seaweeds biomass from intertidal rocky shores of Qeshm Island, Persian Gulf. Int J Mar Sci Eng. 2012;2:101–6.

Hassanzadeh S, Hosseinibalam F, Rezaei-Latifi A. Numerical modelling of salinity variations due to wind and thermohaline forcing in the Persian Gulf. App Math Model. 2011;35:1512–37.

Hewitt JE, Thrush SF, Dayton PK, Bonsdorff E. The effect of spatial and temporal heterogeneity on the design and analysis of empirical studies of scale dependent systems. Am Nat. 2007;169:398–408.

Ingo´ lfsson A. Community structure and zonation patterns of rocky shores at high latitudes: an interocean comparison. J Biogeogr. 2005;32:169–82.

Jha B, Reddy CRK, Thakur MC, Rao MU. Seaweeds of India. 2009. Springer Science & Business Media.

John DM. Marine algae (Seaweeds) associated with coral reefs in the gulf. In: Riegl BM, Purkis SJ, editors. Coral Reefs of the Gulf: Adaptation to Climatic Extremes. Springer Science+Business Media; 2012. pp. 309–335. DOI:10.1007/978-94-007-3008-3_14.

Jørgensen SE, Costanza R, Xu FL. Handbook of ecological indicators for assessment of ecosystem health. New York: Taylor & Francis CRC press book; 2005.

Kang JC, Kim MS. Seasonal variation in depth-stratified macroalgal assemblage patterns on Marado, Jeju Island, Korea. Algae. 2012;27:269–81.

Kim SK. Handbook of Marine Macroalgae (Biotechnology and Applied Phycology). West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2012.

Koch M, Bowes G, Ross C, Zhang XH. Climate change and ocean acidification effects on seagrasses and marine macroalgae. Glob Chang Biol. 2013;19:103–32.

Kokabi M, Yousefzadi M. Checklist of the marine macroalgae of Iran. Bot Mar. 2015;58:307–20.

Leopardas V, Uy W, Nakaoka M. Benthic macrofaunal assemblages in multispecific seagrass meadows of the southern Philippines: variation among vegetation dominated by different seagrass species. J Exp Mar Biol Ecol. 2014;457:71–80.

Martínez B, Pato LS, Rico JM. Nutrient uptake and growth responses of three intertidal macroalgae with perennial, opportunistic and summer-annual strategies. Aquat Bot. 2012;96:14–22.

Moreira AR, Armenteros M, Gómez M, Leon AR, Cabrera R, Castellanos ME, Muñoz A, Suarez AM. Variation of macroalgae biomass in Cienfuegos Bay, Cuba. Rev Investig Mar. 2006;27:3–12.

Nybakken JW. Marine biology an ecological approach. New York: Harper Collins College Publishers; 1993. p. 10022.

Orlando-Bonaca M, Lipej L, Orfanidis S. Benthic macrophytes as a tool for delineating, monitoring and assessing ecological status: the case of Slovenian coastal waters. Mar Pollut Bull. 2008;56:666–76.

Pedersen MF, Borum J, Leck FF. Phosphorus dynamics and limitation of fast- and slow-growing temperate seaweeds in Oslofjord, Norway. Mar Ecol Prog Ser. 2010;399:103–15.

Phillips JC, Hurd CL. Nitrogen ecophysiology of intertidal seaweeds from New Zealand: N uptake, storage and utilisation in relation to shore position and season. Mar Ecol Prog Ser. 2003;264:31–48.

Raffo MP, Lo RV, Schwindt E. Introduced and native species on rocky shore macroalgal assemblages: zonation patterns, composition and diversity. Aquat Bot. 2014;112:57–65.

Sangil C, Sansón M, Afonso-Carrillo J. Spatial variation patterns of subtidal seaweed assemblages along a subtropical oceanic archipelago: thermal gradient vs herbivore pressure. Estuar Coast Shelf Sci. 2011;94:322–33.

Scrosati R, Heaven C. Spatial trends in community richness, diversity, and evenness across rocky intertidal environmental stress gradients in Eastern Canada. Mar Ecol Prog Ser. 2007;342:1–14.

Smale DA, Kendrick GA, Wernberg T. Assemblage turnover and taxonomic sufficiency of subtidal macroalgae at multiple spatial scales. J Exp Mar Biol Ecol. 2010;384:76–86.

Sohrabipour J, Rabiei R. A list of marine algae from seashores of Iran (Hormozgan Province). Qatar Univ Sci J. 1999;19:312–37.

Sohrabipour J, Rabiei R. The checklist of green algae of the Iranian coastal lines of the Persian Gulf and Gulf of Oman. Iranian Journal of Botany. 2007;13:146–9.

Sohrabipour J, Nejadsatari T, Assadi M, Rabiei R. The marine algae of the southern coast of Iran, Persian Gulf, Lengeh area. Iranian Journal of Botany. 2004;10:83–93.

Thongroy P, Liao LM, Prathep A. Diversity, abundance and distribution of macroalgae at Sirinart Marine National Park, Phuket Province, Thailand. Bot Mar. 2007;50:88–96.

Trono GC. Field guide and Atlas of the seaweed resources of the Philippines. Makati City: Bookmark, Inc.; 2003.

Vaz-Pinto F, Martínez B, Olabarria C, Arenas F. Neighbourhood competition in coexisting species: the native Cystoseira humilisvs the invasive Sargassum muticum. J Exp Mar Biol Ecol. 2014;454:32–41.

Williams SL, Bracken ME, Jones E. Additive effects of physical stress and herbivores on intertidal seaweed biodiversity. Ecology. 2013;94:1089–101.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks the Mangrove Forest Research Center of University of Hormozgan for financial support of this project.

Authors’ contributions

MK carried out the identification of macroalgae and monthly sampling. MY conceived of the study and participated in its design and coordination. MR participated in the design of the study and performed the statistical analysis. MAF cooperated in the identification and also the field studies. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Kokabi, M., Yousefzadi, M., Razaghi, M. et al. Zonation patterns, composition and diversity of macroalgal communities in the eastern coasts of Qeshm Island, Persian Gulf, Iran. Mar Biodivers Rec 9, 96 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41200-016-0096-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41200-016-0096-4