Abstract

Background

Formamides are common motifs of biologically-active compounds (e.g. formylated peptides) and are frequently employed as intermediates to yield a number of other functional groups. A rapid, simple and reliable route to [carbonyl-11C]formamides would enable access to this important class of compounds as in vivo PET imaging agents.

Results

A novel radiolabelling strategy for the synthesis of carbon-11 radiolabelled formamides ([11C]formamides) is presented. The reaction proceeded with the conversion of a primary amine to the corresponding [11C]isocyanate using cyclotron-produced [11C]CO2, a phosphazene base (2-tert-butylimino-2-diethylamino-1,3-dimethylperhydro-1,3,2-diazaphosphorine, BEMP) and phosphoryl chloride (POCl3). The [11C]isocyanate was subsequently reduced to [11C]formamide using sodium borohydride (NaBH4). [11C]Benzyl formamide was obtained with a radiochemical yield (RCY) of 80% in 15 min from end of cyclotron target bombardment and with an activity yield of 12%. This novel method was applied to the radiolabeling of aromatic and aliphatic formamides and the chemotactic amino acid [11C]formyl methionine (RCY = 48%).

Conclusions

This study demonstrates the feasibility of 11C-formylation of primary amines with the primary synthon [11C]CO2. The reactivity is proportional to the nucleophilicity of the precursor amine. This novel method can be used for the production of biomolecules containing a radiolabelled formyl group.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Positron emission tomography (PET) is a non-invasive imaging technique for the in vivo detection and monitoring of normal and abnormal molecular function in health and disease (Miller et al. 2008). PET relies on the administration of radiopharmaceuticals labelled with positron-emitting radionuclides (Miller et al. 2008; Antoni 2015; Conti and Eriksson 2016). Of all the available positron-emitting radionuclides, carbon-11 (11C) is a valuable choice due to the ubiquity of carbon atoms in biologically-active compounds (Miller et al. 2008; Conti and Eriksson 2016) and substituting a stable carbon atom with its positron-emitting isotope maintains the chemical and biological properties of the compound (Miller et al. 2008; Rotstein et al. 2013). However, the rapid radioactive decay of 11C (radioactive half-life t1/2 = 20.4 min) requires a rapid incorporation of carbon-11 into the target molecule to avoid activity losses during the synthesis procedure (Dahl et al. 2017). A constraint of currently used carbon-11 radiolabelling strategies is the limited choice of cyclotron-produced primary synthons available for radiolabelling (Miller et al. 2008) which are either [11C]carbon dioxide ([11C]CO2) or [11C]methane ([11C]CH4) when an oxidizing or reducing environment, respectively, are used during the proton irradiation of a nitrogen gas target (Miller et al. 2008). Despite its low chemical reactivity, [11C]CO2 has been utilized as a synthon for direct incorporation of carbon-11 into radiopharmaceuticals (Miller et al. 2008; Rotstein et al. 2013; Deng et al. 2019).

Novel [11C]CO2 direct radiolabelling strategies have been developed based on the electrophilicity of [11C]CO2, significantly improving its applicability as a synthon (Rotstein et al. 2013; Dahl et al. 2017; Deng et al. 2019; Taddei and Gee 2018; Bongarzone et al. 2017; Riss et al. 2012; Krasikova et al. 2009; van der Meij et al. 2003). These strategies include the use of: i) highly reactive nucleophiles (e.g. Grignard reagents or organolithium compounds) to form [11C]carboxylic acids (Rotstein et al. 2013; Krasikova et al. 2009; van der Meij et al. 2003); and ii) superbases, known as CO2-fixation agents, for the carboxylation of boronic esters, amines and alcohols (Rotstein et al. 2013; Dahl et al. 2017; Deng et al. 2019; Taddei and Gee 2018; Bongarzone et al. 2017; Riss et al. 2012). Superbases, such as 1,8-diazabicyclo[5.4.0]undec-7-ene (DBU) and 2-tertbutylimino-2-diethylamino-1,3-dimethyl-perhydro-1,3,2- diazaphosphorine (BEMP) (Dahl et al. 2017; Deng et al. 2019; Taddei and Gee 2018; Bongarzone et al. 2017), are capable of increasing [11C]CO2 solubility and reactivity by creating labile bonds with [11C]CO2 and have enabled the rapid and reliable synthesis of [11C]carboxylic acids (Riss et al. 2012), [11C]amides (Bongarzone et al. 2017; Aubert et al. 1997), [11C]ureas (Downey et al. 2018; Haji Dheere et al. 2013), [11C]isocyanates (Wilson et al. 2011), [11C]carbonates (Haji Dheere et al. 2018).

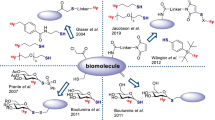

To date, direct formamide labelling is not accessible by current 11C-synthesis methods although the formamidic motif is found in several biologically-active molecules, such as the vitamin B1 analogue octotiamine, the thiamine analogue fursultiamine (Seddighi et al. 2015), and the chemotactic peptide formyl methionine (Schiffmann et al. 1975). Moreover, the formamidic group is a versatile intermediate due to its high chemical reactivity and can be used in electrophilic aromatic substitution to form aryl aldehydes (Downie et al. 1993) or to perform ring-closure reactions (Horkka et al. 2019; Schou and Halldin 2012). It is also a valuable reagent in the synthesis of isocyanides (Guchhait et al. 2013), quinolines (Jackson and Meth-Cohn 1995) and formamidines (Han and Cai 1997).

The availability of a simple and robust 11C-formamide radiolabelling method would enable access to formamide-containing PET imaging agents as well as carbon-11 labelled formamides as radiosynthetic intermediates.

Herein, we report a rapid one-pot radiosynthesis of [11C]formamides from primary amines and cyclotron-produced [11C]CO2 (Scheme 1) using [11C]CO2-fixation chemistry strategies. In the presence of BEMP as superbase and a primary amine, the reaction proceeds via the initial formation of a [11C]isocyanate intermediate as described by Wilson et al. (Wilson et al. 2011). [11C]CO2 is trapped in a solution of benzylamine and BEMP, initially forming the corresponding [carbonyl-11C]carbamate on the aminic function (Wilson et al. 2011). The addition of a superbase serves to deprotonate the primary amine (pKa BEMP = 27.6, pKa benzylamine = 8.82), making it more reactive towards the delivered [11C]CO2 and helping the trapping of activity in the reaction vial. The subsequent addition of phosphorus(V) oxychloride (POCl3) dehydrates the [11C]carbamate, yielding the [11C]isocyanate intermediate ([11C]1, Scheme 1) (Wilson et al. 2011) which is subsequently reduced by an excess of sodium borohydride (NaBH4), yielding the desired [11C]formamide derivative [11C]3 (Scheme 1). Aliphatic and aromatic amines were also tested to investigate the applicability of the method on different chemotypes. Furthermore, the radiolabelling of the chemotactic aminoacid [carbonyl-11C]formyl methionine ([11C]16, Scheme 2) (Schiffmann et al. 1975) is reported.

Proposed reaction scheme for the one-pot synthesis of [11C]formamides. Reaction conditions: a benzylamine (4.7 μmol, 1 equiv.), BEMP (3.7 equiv.), diglyme (75 μL), [11C]CO2, 0–20 °C, 2 min, followed by POCl3 (11.5 equiv.) in diglyme (75 μL), 0–20 °C, 2 min. b NaBH4 (5–15 equiv.), diglyme (50 μL), 0–60 °C, 2–15 min

Radiolabelling of [carbonyl-11C] formyl methionine tBu ester ([11C]15) and subsequent deprotection to form [carbonyl-11C] formyl methionine ([11C]16). Reaction conditions: a methionine tBu ester (4.7 μmol, 1 equiv.), BEMP (34.6 μmol, 7.4 equiv.), diglyme (75 μL), [11C]CO2, 0 °C, 2 min, then POCl3 (54.05 μmol, 11.5 equiv.) in diglyme (75 μL), 0 °C, 2 min. b NaBH4 (2.67 mg, 15 equiv.), diglyme (50 μL), 0 °C, 10 min. c TFA (200 μL), 20 °C, 2 min

Results and discussion

Initial experiments focused on studying the formation of [11C]1 following the method described by Wilson et al. (2011). By combining benzylamine (4.7 μmol, 1 equiv.), BEMP (3.7 equiv.), [11C]CO2 from the cyclotron target and POCl3 (11.5 equiv.) in diglyme (150 μL) at 20 °C for 4 min, [11C]1 was yielded in modest radiochemical yields (RCY = 63%) (Determined by radio-HPLC analysis of the crude product n.d.) together with the 11C-labelled symmetric urea as a byproduct ([11C]2, RCY = 31% Scheme 1). The cyclotron-produced [11C]CO2 was quantitatively trapped in the reaction mixture (trapping efficiency (TE) > 95%) (28). Trapping efficiency (TE) of cyclotron-produced [11C]CO2 into the reaction vial was calculated by dividing the activity of the reaction vial by the total activity delivered by the cyclotron (reaction vial + ascarite).

In order to improve the RCY of [11C]1, we opted to decrease the temperature of the reaction - as lowering the temperature might reduce the reactivity of [11C]1 towards the unreacted primary amine in solution (hence decreasing the formation of [11C]2). Indeed, decreasing the temperature from 20 to 0 °C significantly increased the RCY of [11C]1 from 63% to 81%.

Encouraged by the increased RCY of [11C]1, we focused on its reduction to [carbonyl-11C]benzyl formamide ([11C]3, Scheme 1, Table 1). As observed in previous non-radioactive work, the reduction of isocyanates (1 equiv.) is achieved using a high excess of lithium aluminium hydride (LiAlH4, 15 equiv.) (Finholt et al. 1953) or sodium borohydride (NaBH4, 15 equiv.) (Ellzey and Mack 1963) at high temperatures (> 160 °C). The reduction step was developed starting from the latter method as the milder reducing agent NaBH4 would allow broader substrate scope in the method applicability. When 15 equivalents of NaBH4 were used at 150 °C for 15 min, high amounts of the undesired [11C]2 (47%) and a polar unknown radioactive by-product (53%) were formed instead of [11C]3 (entry 1, Table 1). [11C]2 is not affected by these conditions and remains unchanged. The failure of the reduction might be due to the harsh conditions applied (15 equiv. of reducing agent, high temperature and long reaction time), thus milder conditions were tested by a concomitant decrease of the equivalents of NaBH4 (10 equiv.), temperature (20 °C) and reaction time (10 min). As a result, the desired [11C]3 was obtained in good yield (RCY = 33%, entry 2, Table 1).

With the aim to increase the RCY of [11C]3, a further optimization study was performed by varying a single parameter (equivalents of reducing agent, temperature, reduction time) per experiment (entries 3–9, Table 1). Lowering the equivalents of NaBH4 from 10 to 5 had a detrimental effect on the RCY of [11C]3 (33% in entry 2 versus 2% in entry 3, Table 1) which can be explained by the lower availability of hydride ions in solution to accomplish the reduction and is consistent with the high amount of unreacted [11C]1 found in the mixture (77%, entry 3, Table 1). On the other hand, increasing the amount of NaBH4 from 10 to 15 equivalents showed a modest increase in [11C]3 RCY from 33% to 57% (entry 2 versus entry 4, Table 1).

Next, we studied the effect of the temperature on the RCY of [11C]3. Increasing the temperature from 20 to 60 °C lowered the formation of [11C]3 from 57% to 42% (entry 4 versus entry 5, Table 1). A further increase in temperature to 150 °C did not yield [11C]3 (entry 1, Table 1). Lowering the temperature to 0 °C, instead, increased the RCY of [11C]3 from 57% to 80% (entry 4 versus entry 6, Table 1). Hence, [11C]formamide formation is temperature dependent and favoured at low temperatures whereas higher temperatures promote the formation of the undesired [11C]2 (9% at 0 °C, entry 6, 16% at 20 °C, entry 4, 38% at 60 °C, entry 5, 47% at 150 °C, entry 1, Table 1).

The influence of the reaction time on the RCY of [11C]3 was also explored by performing the reduction with NaBH4 for 2, 5 and 15 min. When the reaction was allowed to proceed for 15 min, no significant change on the RCY of [11C]3 was observed (79% versus 80%, entry 7 versus entry 6, Table 1). Decreasing the reduction time from 10 to 5 or 2 min still resulted in good yields of [11C]3 (60% and 60% at 5 or 2 min, respectively, entries 8 and 9, Table 1). After a reaction time of either 5 or 2 min, however, the reaction did not reach completion with the unreacted [11C]1 still being present in the mixture (14% and 8%, respectively, entries 8 and 9, Table 1).

In summary, this optimisation process allowed us to produce [11C]3 from benzyl amine and [11C]CO2 with good RCY (80%, entry 6, Table 1, Fig. 1) and high TE (> 95%) in 15 min from the release of [11C]CO2 from the cyclotron target and an activity yield of 12% and a molar activity (Am) of 5 ± 2 \( \frac{GBq}{\mu mol} \) (decay-corrected at end of bombardment (EOB) with an initial delivery of 300 MBq of [11C]CO2).Footnote 1

Radioactive traces of the analytical HPLC evaluation (entry 6, Table 1) a after [11C]1 synthesis; b after [11C]3 synthesis

To study the scope of the reaction, the aforementioned reaction conditions were subsequently applied to a number of amines (4, 6, 8 and 10) to produce the corresponding [carbonyl-11C] formamides ([11C]5, [11C]7, [11C]9 and [11C]11, Table 2).

Initially, the effect of the spacer between the amine group and the phenyl ring was investigated by adding one extra carbon on the alkyl chain of benzylamine. Correspondingly, 2-phenethylamine (4) was used as starting material. Whilst the TE was slightly lower than that observed with [11C]3 ([11C]3 > 95% and [11C]5 = 89 ± 5%, entry 1, Table 2), the product [11C]N-(phenethyl) formamide ([11C]5) was achieved with a higher RCY ([11C]3 = 80 ± 4% and [11C]5 = 84 ± 4%), which might be explained by the higher nucleophilicity of 4 (pKa benzylamine = 8.82 versus pKa 4 = 9.73).

The reactivity of a hindered primary amine was also studied by employing cyclohexylamine (6) as a substrate. As expected, both TE and RCY of [11C]N-cyclohexylformamide ([11C]7) were lower than other amines tested (TE = 67%; RCY = 73%, entry 2, Table 2) due to the lower nucleophilicity of the substrate and the steric hindrance that partly impede the reaction.

Aromatic amines were subsequently tested by using activated (p-toluidine, 8, pKa = 5.10) and deactivated (p-nitroaniline, 10, pKa = 1.01) aromatic rings. Testing these two amines would also reveal the effect of different substitution patterns on the reactivity of the substrate. When 8 was used as a substrate, the TE was significantly lower than previous entries (27%, entry 3, Table 2) and the respective [11C]p-formotoluidide ([11C]9) was obtained with low RCY (6%, entry 3, Table 2). Using deactivated aromatic rings such as 10 further lowered the TE (11%, entry 4) and did not yield any product. These results are in line with previous findings where aromatic amines had shown low [11C]CO2 trapping and reactivity (Wilson et al. 2011) and highlight the relevance of aromatic ring substituents, with activated rings being more reactive than deactivated aromatic systems. These experiments also highlight the importance of the basicity of the starting amine: precursors with higher basicity will bind the delivered [11C]CO2 with higher TE, resulting in higher RCY (Figure SI5, Supplementary Information). The radiolabelling of a secondary amine as a negative control was also tested (entry 5, Table 2) to confirm the reaction mechanism. The use of a secondary amine would indeed prevent the formation of the [11C]isocyanate intermediate, thus impeding the proceeding of the reaction. When N-benzylmethylamine (12) was used as a substrate, the product [11C]N-benzyl-N-methylformamide ([11C]13) was not formed.

Next, this novel radiolabelling strategy was applied to the synthesis of the chemotactic peptide [carbonyl-11C] formyl methionine (Scheme 2) by using the hydrochloric form of the tert-butyl (tBu) ester of methionine as starting material. The cyclotron-produced [11C]CO2 was delivered at 0 °C in the reaction vial containing methionine tBu-ester and BEMP. The subsequent addition of POCl3 and the reaction for 2 min at 0 °C formed the [11C]isocyanate analogue ([11C]14, Scheme 2). [11C]14 was then reduced with an excess of NaBH4 for 10 min to yield [carbonyl-11C]tBu-formylmethioninate ([11C]15, Scheme 2) in good RCY (57%). The tBu protecting group was subsequently removed by adding TFA (200 μL) at r.t. for 2 min, forming the desired [carbonyl-11C]formyl methionine ([11C]16, Scheme 2) with a RCY of 48% within 18 min from EOB.

Conclusions

In summary, this proof-of-concept study demonstrates the feasibility of direct 11C-formylation of aromatic and aliphatic primary amines using the primary synthon [11C]CO2. The reaction proceeds via the formation of a [11C]isocyanate intermediate via [11C]CO2 fixation chemistry. The [11C]isocyanate was subsequently reduced to the [11C]formamidic analogue. The total processing time was 15 min (EOB to end of synthesis (EOS)), with [11C]3 produced in high RCY (80%) and high TE (> 95%). To confirm the applicability of the developed method, an array of aliphatic and aromatic amines was tested. When aliphatic amines were used, the respective [11C]formamides were produced in high yields (RCYs = 74–83%), whereas aromatic amines showed little-to-no reactivity (RCYs = 0–6%). Thus, the reactivity is related to the nucleophilicity of the amine. The radiolabelling of a secondary amine as negative control was attempted, as well, resulting in no formation of the desired product and confirming the reaction mechanism. Furthermore, the radiolabelling of the biologically-relevant compound [carbonyl-11C]formyl methionine was successfully attempted with a RCY of 48% (Determined by radio-HPLC analysis of the crude product n.d.) in 18 min from EOB to EOS. This method could be applied to the radiolabelling of an array of formylated radiopharmaceuticals including the chemotactic peptide [11C]N-formylmethionine-leucyl-phenylalanine ([11C]fMLP) to study inflammation and [11C]formoterol for the imaging of β2 adrenergic receptors in pulmonary diseases.

Methods

Carbon-11 chemistry

N-benzylamine (99%), 2-tertbutylimino-2-diethylamino-1,3-dimethyl-perhydro-1,3,2-diazaphosphorine (BEMP), phosphorus(V) oxychloride (POCl3), sodium borohydride (NaBH4), benzyl isocyanate, N-formyl methionine, di-tert-butyl dicarbonate and anhydrous diethylene glycol dimethyl ether (diglyme, 99.5%) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Tert-butyl alcohol and N-benzyl formamide (99%) was purchased from Alfa Aesar. The purchased N-benzyl formamide and benzyl isocyanate were used as HPLC reference. N-formyl methionine was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, L-methionine t-butyl ester hydrochloride was purchased from ChemCruz.

The reactions were performed in oven-dried v-shaped vials (KX Microwave Vials, 5 mL) sealed with crimp caps (Fisherbrand, centre hole with 3.0 mm PTFE seal aluminum silver 20 mm, part #10132712). All gas transfer lines were fabricated from PTFE tubing (length: 10–30 cm, O.D.: 0.79 × 0.4 in., I.D.: 1/32 × 0.16 in.).

[11C]CO2 was produced using a Siemens RDS112 cyclotron by the 11 MeV proton bombardment of nitrogen (+ 0.5% O2) gas via the 14N(p,α)11C reaction. The cyclotron-produced [11C]CO2 was bubbled in a stream of helium gas with a flow rate of 60 mL/min post target depressurisation directly into an oven-dried v-shaped vial without further gas processing (time from end of bombardment (EOB) to end of delivery (EOD) = 1 min and 50 s).

The reactions were performed on a semi-automatic Eckert & Ziegler (E&Z) Modular-Lab radiochemistry synthesis module.

HPLC analysis was performed on an Agilent 1200 system equipped with a UV detector (λ = 214/254 nm) and a β+-flow detector coupled in series.

A P2O5 trap and a one-way valve (BRAUN, normally closed backcheck valve, part #415062) were placed before the vial. An ascarite® trap consisting of a cartridge (Supelco, Empty Reversible SPE Tube, non-fluorous polypropylene volume 1 mL) filled with ascarite (Sigma-Aldrich, 1310-73-2) was placed after the Vial to trap any unreacted [11C]CO2. A waste bag (Tedlar® gas sampling bag, 3.8 L capacity with septum) was placed at the outlet to prevent any gaseous emission.

The reaction vial containing N-benzylamine and BEMP in anhydrous diglyme was initially placed in the reactor and the temperature was set at 0 °C.

A cyclotron beam current of 5 μA was maintained for a bombardment time of 1 min for all reaction optimization experiments producing ~ 300 MBq of carbon-11. The cyclotron-produced [11C]CO2 was bubbled into the reaction vial in a stream of helium gas with a flow rate of 50–60 mL/min post target depressurisation. An ascarite trap and a waste bag were attached to the vial via a vent needle to avoid activity loss in the environment (Fig. 2).

At end of delivery (EOD), a solution of POCl3 (11.5 equiv.) in anhydrous diglyme was added in the reaction vial. The magnetic agitation was turned on and the reaction occurred for 2 min. A solution of NaBH4 (5–15 equiv.) in anhydrous diglyme was subsequently added to the main reaction vial, leaving it to react for 2–15 min (Fig. 2).

Graphical representation of the set-up used for the reaction. a The reaction vial is connected directly to the cyclotron target to allow the delivery of [11C]CO2. An ascarite trap and waste bag are placed after the reaction vial to trap any [11C]CO2 not fixed in the reaction vial. b The reaction vial is disconnected from the cyclotron target line and from the waste bag to avoid loss of [11C]CO2 during the reaction steps. Then POCl3 is added. c NaBH4 addition

The reaction was then quenched with 300 μL of mobile phase composed of water and acetonitrile (H2O:ACN) 60:40. To avoid overpressure of gases inside the vial due to free hydrogen production, a waste bag was attached to the vial via a vent needle.

The trapping of cyclotron-produced [11C]CO2 into the reaction vial was calculated by dividing the activity of the reaction vial by the total activity delivered from the cyclotron (reaction vial + ascarite).

An aliquot of the crude was injected in the radio-HPCL in order to determine the RCY.

Molar activity calculation for [11C]3

Eight samples of 3 at different concentrations (0.2–0.00039 mM) were analysed by HPLC to obtain a calibration curve of the peak area (mAU*s) versus μmol/mL (Figure SI4). The peak areas of 3 were averaged and plotted in function of the corresponding μmol/mL.

An aliquot of purified [11C]3 (20 μL) was analysed by analytical radioHPLC and the UV peak corresponding to 3 was integrated. The area of the UV peak was used to determine the μmol/mL of the associated 12C-carrier content for [11C]3 from the equation of the calibration curve. The molar activity (Am) of [11C]3 was calculated to be 4.57 ± 1.99 GBq/μmol (n = 3) decay-corrected at EOB with an initial delivery of 300 MBq.

Synthesis of tert butyl-formylmethioninate (13)

N-formyl methionine (1 equiv., 564 μmol) and tert-butyl alcohol (2 equiv., 1128 μmol) were mixed in an oven-dried v-shaped vial. The reaction vial was then put into an oil bath at a temperature of 45 °C. Subsequently, di-tert-butyl dicarbonate (0.7 equiv., 394.8 μmol) and magnesium chloride (0.1 equiv., 56.4 μmol) were added in the reaction mixture. The vial was crimped and the reaction stirred for 48 h at 45 °C (Scheme 3).

After, the crimped vial was cooled to room temperature and the reaction mixture was quenched with 10 mL of water. Three aliquots of 10 mL of dichloromethane were used to extract the product. The organic fractions were then washed with a saturated solution of sodium bicarbonate, dried on anhydrous magnesium sulphate and evaporated in vacuo.

The compound was characterized via reverse-phase HPLC using an analytical column (Phenomenex Luna, 5 μm C18, 150 × 4.6 mm) with a flow rate of 1 mL/min. The gradient was isocratic until 2:30 min (ACN:H2O, 20:80), linear between 2:30–10 min (up to ACN:H2O, 95:5), isocratic between 10 and 13 min (ACN:H2O, 95:5) and linear between 13 and 14 min to return to initial conditions (ACN:H2O, 20:80) which were kept isocratic until the end of the run (17 min). The detected retention time was tr = 8 min and 40 s (Figure SI5B).

1H-NMR was performed on Bruker AVANCE III HD 400 MHz.

1H-NMR of 13 (CDCl3): δ 1.20 (s, 9H), 1.42 (s, 3H), 2.00–2.09 (m, J = 8.67 Hz, 2H), 2.40–2.50 (m, J = 9.25, 2H), 3.52 (s, 1H), 7.20 (s, 1H).

13C-NMR of 13 (CDCl3): δ 14.81, 26.53, 32.04, 52.95, 81.28, 163.46, 170.16.

MASS (m/z): 234.10.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article (and its supplementary information files).

Notes

This work describes a method development study using short, low current, cyclotron irradiations where obtaining high Am were not the main focus. However, the associated carrier content of compound [11C]3 was in the range of 12–14 nmol in 3 mL. Assuming that the stable 12C carrier content would be in the same range for a standard clinical [11C]CO2 production, it is estimated that molar activities of 290–570 \( \frac{GBq}{\mu mol} \) would be obtained (decay-corrected at EOB).

Abbreviations

- 11C:

-

Carbon-11

- [11C]CH4 :

-

Carbon-11 labelled methane

- [11C]CO2 :

-

Carbon-11 labelled carbon dioxide

- Am :

-

Molar activity

- BEMP:

-

2-tert-butylimino-2-diethylamino-1,3-dimethylperhydro-1,3,2-diazaphosphorine

- DBU:

-

1,8-diazabicyclo [5.4.0] undec-7-ene

- EOB:

-

End of bombardment

- EOS:

-

End of synthesis

- NaBH4 :

-

Sodium borohydride

- PET:

-

Positron emission tomography

- POCl3 :

-

Phosphorus(V)oxychloride

- RCY:

-

Radiochemical yield

- TE:

-

Trapping efficiency

References

Antoni G. Development of carbon-11 labelled PET tracers—radiochemical and technological challenges in a historic perspective. J Labelled Comp Radiopharm. 2015;58(3):65–72.

Aubert C, Huard-Perrio C, Lasne M-C. Rapid synthesis of aliphatic amides by reaction of carboxylic acids, Grignard reagent and amines: application to the preparation of [11C]amides. J Chem Soc Perkin Trans. 1997;19:2837–42.

Bongarzone S, Runser A, Taddei C, Dheere AKH, Gee AD. From [11C]CO2 to [11C]amides: a rapid one-pot synthesis via the Mitsunobu reaction. Chem Commun. 2017;53(38):5334–7.

Conti M, Eriksson L. Physics of pure and non-pure positron emitters for PET: a review and a discussion. EJNMMI Phys. 2016;3(1):8.

Dahl K, Halldin C, Schou M. New methodologies for the preparation of carbon-11 labeled radiopharmaceuticals. Clin Transl Imaging. 2017;5(3):275–89.

Deng X, Rong J, Wang L, Vasdev N, Zhang L, Josephson L, et al. Chemistry for positron emission tomography: recent advances in (11) C-, (18) F-, (13) N-, and (15) O-labeling reactions. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2019;58(9):2580–605.

Determined by radio-HPLC analysis of the crude product. (n.d.).

Downey J, Bongarzone S, Hader S, Gee AD. In-loop flow [(11) C]CO2 fixation and radiosynthesis of N,N′-[(11) C]dibenzylurea. J Labelled Comp Radiopharm. 2018;61(3):263–71.

Downie IM, Earle MJ, Heaney H, Shuhaibar KF. Vilsmeier formylation and glyoxylation reactions of nucleophilic aromatic compounds using pyrophosphoryl chloride. Tetrahedron. 1993;49(19):4015–34.

Ellzey SE, Mack CH. Interaction of phenyl Isocyanate and related compounds with sodium borohydride. J Org Chem. 1963;28(6):1600–4.

Finholt AE, Anderson CD, Agre CL. The reduction of isocyanates and isothiocyanates with lithium aluminum hydride. J Org Chem. 1953;18(10):1338–40.

Guchhait SK, Priyadarshani G, Chaudhary V, Seladiya DR, Shah TM, Bhogayta NP. One-pot preparation of isocyanides from amines and their multicomponent reactions: crucial role of dehydrating agent and base. RSC Adv. 2013;3(27):10867–74.

Haji Dheere AK, Bongarzone S, Shakir D, Gee A. Direct incorporation of [11C]CO2 into asymmetric [11C]carbonates. J Chem. 2018;2018:4.

Haji Dheere AK, Yusuf N, Gee A. Rapid and efficient synthesis of [11C] ureas via the incorporation of [11C]CO2 into aliphatic and aromatic amines. Chem Commun. 2013;49(74):8193–5.

Han Y, Cai L. An efficient and convenient synthesis of formamidines. Tetrahedron Lett. 1997;38(31):5423–6.

Horkka K, Dahl K, Bergare J, Elmore CS, Halldin C, Schou M. Rapid and efficient synthesis of 11C-labeled Benzimidazolones using [11C] carbon dioxide. ChemistrySelect. 2019;4(6):1846–9.

Jackson A, Meth-Cohn O. A new short and efficient strategy for the synthesis of quinolone antibiotics. Chem Commun. 1995;(13):1319..

Krasikova RN, Andersson J, Truong P, Nag S, Shchukin EV, Halldin C. A fully automated one-pot synthesis of [carbonyl-11C]WAY-100635 for clinical PET applications. Appl Radiat Isot. 2009;67(1):73–8.

Miller PW, Long NJ, Vilar R, Gee AD. Synthesis of 11C, 18F, 15O, and 13N radiolabels for positron emission tomography. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2008;47(47):8998–9033.

Riss PJ, Lu S, Telu S, Aigbirhio FI, Pike VW. Cu(I)-catalyzed (11) C carboxylation of boronic acid esters: a rapid and convenient entry to (11) C-labeled carboxylic acids, esters, and amides. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2012;51(11):2698–702.

Rotstein BH, Liang SH, Holland JP, Collier TL, Hooker JM, Wilson AA, et al. 11CO2 fixation: a renaissance in PET radiochemistry. Chem Commun. 2013;49(50):5621–9.

Schiffmann E, Corcoran BA, Wahl SM. N-formylmethionyl peptides as chemoattractants for leucocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1975;72(3):1059–62.

Schou M, Halldin C. Radiolabeling of two 11C-labeled formylating agents and their application in the preparation of [11C]benzimidazole. J Labelled Comp Radiopharm. 2012;55(13):460–2.

Seddighi M, Shirini F, Mamaghani M. An efficient method for the synthesis of formamidine and formamide derivatives promoted by sulfonated rice husk ash (RHA-SO3H). J Iran Chem Soc. 2015;12(3):433–9.

Taddei C, Gee AD. Recent progress in [11C]carbon dioxide ([11C]CO2) and [11C]carbon monoxide ([11C]CO) chemistry. J Labelled Comp Radiopharm. 2018;61(3):237–51.

van der Meij M, Carruthers NI, Herscheid JDM, Jablonowski JA, Leysen JE, Windhorst AD. Reductive N-alkylation of secondary amines with [2-11C]acetone. J Labelled Comp Radiopharm. 2003;46(11):1075–85.

Wilson AA, Garcia A, Houle S, Sadovski O, Vasdev N. Synthesis and application of isocyanates radiolabeled with carbon-11. Chemistry. 2011;17(1):259–64.

Acknowledgements

Non applicable.

Funding

King’s College London and UCL Comprehensive Cancer Imaging Centre is funded by the CRUK and EPSRC in association with the MRC and DoH (England). The research was supported by the Wellcome’s Multi-User Equipment ‘A multiuser radioanalytical facility for molecular imaging and radionuclide therapy research’ [212885/Z/18/Z]. It was additionally supported by the Wellcome/EPSRC Centre for Medical Engineering at King’s College London [WT 203148/Z/16/Z] and the EPSRC Centre for Doctoral Training in Medical Imaging [EP/L015226/1].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Federico Luzi: Conception and design of the work, acquisition and analysis of the data, has approved the submitted version. He also has agreed both to be personally accountable for the author’s own contributions and to ensure that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work, even ones in which the author was not personally involved, are appropriately investigated, resolved, and the resolution documented in the literature. Antony Gee: Conception and design of the work, revision, has approved the submitted version. He also has agreed both to be personally accountable for the author’s own contributions and to ensure that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work, even ones in which the author was not personally involved, are appropriately investigated, resolved, and the resolution documented in the literature. Salvatore Bongarzone: Conception and design of the work, revision, has approved the submitted version. He also has agreed both to be personally accountable for the author’s own contributions and to ensure that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work, even ones in which the author was not personally involved, are appropriately investigated, resolved, and the resolution documented in the literature.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Non applicable.

Consent for publication

Non applicable.

Competing interests

Non applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Luzi, F., Gee, A.D. & Bongarzone, S. Rapid one-pot radiosynthesis of [carbonyl-11C]formamides from primary amines and [11C]CO2. EJNMMI radiopharm. chem. 5, 20 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41181-020-00103-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41181-020-00103-y