Abstract

Background

Due to a lack of data, no study has yet documented differences in adult life expectancy in India by education, caste, and religion.

Objective

To examine disparities in socioeconomic status (SES) in the adult mortality rate (40q30) and life expectancy at age 15 (e15) in India.

Data and methods

We estimated adult mortality by SES with the orphanhood method to analyze information related to the survival of respondents’ parents. We used data from the India Human Development Survey 2011–2012. SES was measured by education, caste, religion, and income of the either deceased adults or their offspring.

Results

A consistency analysis between orphanhood estimates and official statistics confirmed the robustness of the estimates. Mortality is higher among adults who are illiterate, belong to deprived castes or tribes, have children with a low level of education, and have a low level of household income. The adult mortality rate varies marginally by religion in India. Life expectancy at 15 (e15) is about 3.50 and 5.7 years shorter for illiterate men and women, respectively, compared with literate men and women. The parameter e15 also varies significantly by educational attainment of offspring. On average, parents of children educated to higher secondary level (and above) gain an extra 3.8–4.6 years of adult life compared to parents of illiterate children. Disparity in e15 by caste and religion is smaller than disparity by education or income.

Conclusion

The adult mortality burden falls disproportionately on illiterate adults and adults with less educated offspring. Thus, educational disparity in adult mortality appears to be prominent in Indian context. In the absence of adult mortality statistics by SES in India, we recommend that large-scale surveys should continue collecting data to allow indirect techniques to be applied to estimate mortality and life expectancy in the country.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With the advent of Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) in developing countries, numerous studies have assessed socioeconomic gradients in population health, including indicators related to child mortality, nutrition, immunization coverage, morbidities, and access to maternal and child health-care services (Caldwell and McDonald 1982 Wang 2003; Schell et al. 2007; Vikram et al. 2012). These studies repeatedly demonstrate that poor socioeconomic status (SES) is significantly associated with poor health outcomes and low access to health-care facilities, though the extent of disparity by SES varies greatly from one country to another (Houweling and Kunst 2009; Mackenbach et al. 2017). Unlike mortality studies of children under five in developing countries, studies on SES gradients in adult mortality are exceptionally limited due to the lack of a fully functional civil registration system.

Nevertheless, the need for empirical evidence on adult mortality in developing countries has been continuously on the rise. First, most developing countries are experiencing an unprecedented decline in mortality among children under age 5, with most premature deaths shifting to the adult age group. Secondly, the determinants and causes of adult mortality differ substantially from those of under-five mortality, as do SES disparities in adult mortality with regard to its extent and main causes. Careful and separate investigations are thus needed into the magnitude and nature of SES differentials in adult mortality. Thirdly, unlike self-reported health or morbidity, which suffer from reporting bias by socioeconomic characteristics (Dowd and Todd 2011), mortality is still the most objective measure for documenting social disparity in adult health. Finally, trends in adult mortality may not always display the kind of downward slope as it has been experienced by some countries of Sub-Saharan Africa, eastern Europe, and certain subpopulations of the USA (Bradshaw and Timaeus 2006; Guillot et al. 2013; Case and Deaton 2015). Therefore, adult mortality requires particular attention and needs continuous monitoring.

A review of the literature on adult mortality issues in developing countries reveals that researchers have conducted adult mortality studies in at least three different ways: (1) by applying indirect demographic methods such as the sibling survival method (Bicego 1997; Gakidou and King 2006), the orphanhood method (Blacker 1977; Timaeus 1991; Timæus and Jasseh 2004), the widowhood method (Malaker 1986; Saikia et al. 2013), or other census-based methods (Bhat 1998; Bradshaw and Timaeus 2006; (2) by analyzing official statistics on adult mortality wherever available (Saikia et al. 2011; Joubert et al. 2013; Ram et al. 2015); and (3) by using longitudinal data from Demographic Surveillance Systems (DSS) or large cross-sectional sample surveys (Barik et al. 2018; Luo and Xie 2014; Nikoi and Odimegwu 2013).

The first set of studies focused on the trends in adult mortality by age and sex, mostly in Sub-Saharan countries of Africa. We found one study (De Walque and Filmer 2013) that examined the trends and SES gradients in adult mortality in 46 developing countries, but it excluded China and India. The second group of studies is commonly seen on emerging countries like India, China, Brazil, and South Africa and use civil or sample registration system data. However, most of these studies addressed geographical variations in adult mortality rather than differentials by SES, because of the paucity of socioeconomic data. For instance, all studies based on Sample Registration System (SRS) data in India analyzed mortality inequality by type of residence and state, and district (Bhat 1987; Krishnaji and James 2002; Saikia et al. 2011; Ram et al. 2015). Finally, there are some studies on socioeconomic disparity in adult mortality in developing countries in large sample surveys. Using DSS data in African countries, a few studies documented a strong association between SES and adult mortality. Yet, these studies are not nationally representative studies because they are based on small population numbers with low case numbers (Nikoi and Odimegwu 2013; Ashenafi et al. 2017). Using nationally representative sample survey data, a few studies in China and India have documented the association between SES and adult or old-age mortality (Saikia and Ram 2010; Luo and Xie 2014; Barik et al. 2018). However, in these studies, the analysis was limited to show the statistical relationship between socioeconomic conditions and the adult mortality rate. For instance, Saikia and Ram (2010) demonstrated that the risk of death for adults belonging to households with at least one literate person was about 34% lower than in households without any literate person. Barik et al. (2018) found a strong negative relationship between economic status (measured by income, consumption, and ownership of consumer durables) and adult mortality. Yet, neither of these studies estimated mortality by socioeconomic characteristics, nor disparities in adult life expectancy across socioeconomic groups.

In the present study, we aim to extend this literature by estimating differences in adult mortality by SES in India in terms of life expectancy. India is the world’s second most populous country with an extreme demographic and socioeconomic heterogeneity across its subpopulations. To our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate adult mortality rate and adult life expectancy in India by distinct social characteristics. Moreover, our study is the first to use the orphanhood method to estimate adult mortality and life expectancy in India. The next section describes the data and methods we used for the analyses. The results are presented in Section 3, followed by a discussion in which we summarize our main results and conclusions.

Methods and data

Orphanhood method

The “orphanhood method” is based on the information whether the mothers and fathers of the survey respondents are still alive at the time of the interview. The proportion of respondents with mother and father alive is then transferred into a period survival probability from age 25 to age 25 plus a rounded number of years (n) based on the age group of the respondents (l25 + n/l25). A detailed description of the method can be found in Moultrie et al. (2013).

The orphanhood method is based on the assumption that the mortality of parents is not correlated with the mortality of their children. If they were correlated, then the level of adult mortality would be underestimated, as information on the survival of dead children’s parents at the time of the survey would not be reported. Previous studies, however, have found that the selection bias arising from this assumption is small (Palloni et al. 1984) unless the general population is affected by HIV epidemics. As the prevalence rate of HIV–AIDS is negligible in the general population of India, we expect this selection bias to have only a minimal effect.

The orphanhood method estimates the trend in mortality from data for different respondent age-groups. The older the respondent, the longer ago, on average, their parents died. The orphanhood method converts the series of measures of survivorship obtained from different age groups into a series of adult mortality estimates. As the underlying adult mortality levels and patterns are unknown in developing countries, the transformation is based on theoretical population models (Hill et al. 1983; Moultrie et al. 2013). Previous studies suggest that the Indian pattern of adult mortality has an appropriate fit to the South Asian pattern of mortality (Saikia et al. 2013). We thus performed this transformation on the basis of the South Asian pattern of the UN model life tables (United Nations 1982). The best-fitting survival function was used as an estimated life table for a specific period before the time of the survey. The reference period for this life table—i.e., the calendar year to which it is assumed to refer—is derived from the age of the respondents and the level of their parents’ mortality (Brass and Bamgboye 1981).

As respondents from each 5-year age group provide adult mortality estimates corresponding to different time periods, we performed a consistency analysis with official statistics (Sample Registration System) to choose the most suitable age group of the respondents (i.e., the orphanhood estimate that fits best to the official statistics) for our estimation of adult mortality.

Data description

We used data from the second round of the India Human Development Survey (IHDS), 2011–2012, conducted by researchers from the University of Maryland, USA, and the National Council of Applied Economic Research (NCAER), New Delhi, India. The IHDS II is a nationally representative, multi-topic survey of 42,152 households in 1503 villages and 971 urban neighborhoods across India. This data set is publicly available through the Inter-University Consortium for Political and Social Research (ICPSR). The IHDS conducted interviews in each household, on topics such as caste, consumption, income, agriculture, education, health, employment, and gender relations. Children aged 8–11 years completed short reading, writing, and arithmetic tests. In addition, village, school, and medical facility interviews are also available.

We used information available through the eligible women questionnaire. An eligible woman is defined as a woman aged 15–49 who has ever been married (an ever-married woman). The information includes the survival status of their biological parentsFootnote 1 and their parents’ highest educational qualification. The exact questions were (i) “Are your parents still alive?” and (ii) “How many standards/grades did your parents complete?”

To calculate mean age at childbearing for women, we used information on number of births in the last year from the census of 1981 (Additional file 1). Since census data does not give fertility information by income and education of offspring, we applied average age at childbearing for these categories. Further, using census 1981 data, we calculated the average age gap between spouses for the total population to be 6.32 years. To estimate average at childbearing for fathers, we used this gap in all population subgroups.

Variables

Measures for SES

SES can be broadly conceptualized as a person’s position in the social structure. Therefore, the SES of an individual can be measured by different social and economic factors that influence what positions individuals or groups hold within the structure of a society (Krieger et al. 1997; Lynch and Kaplan 2000). A vast body of literature in western countries has documented that SES can be measured through occupation, education, and income (Galobardes et al. 2006; Shavers 2007). Similarly, affiliation to a particular group that may suffer marginalization, such as membership of a majority or minority religion, particularly in developing countries, can also indicate an individual’s SES (Howe et al. 2012).

Yet, some measurements on SES can be unique or more likely to be used in specific countries or regions (Howe et al. 2012). The Indian social stratification system, commonly known as the “caste” system, is a specific measurement of SES in the Indian context. The “caste” or “Jati” is hereditary and cannot be changed across an individual’s life course. There are a large number of Jatis, which have been grouped into four broad categories (varnas): Brahmins (priests), Kshatriyas (warriors), Vaishyas (traders and merchants), and Shudras (menial jobs). Those outside the caste system are referred to as “Dalit,” previously called “untouchables,” and have the lowest social standing. For all governmental or administrative purposes, the castes are categorized into four groups, namely, Scheduled Castes (SCs), Scheduled Tribes (STs), Other Backward Classes (OBCs), and General Castes (non-disadvantaged castes). The SCs (Dalit) and STs (also known as Adivasi) are officially recognized as socially disadvantaged groups. The constitution of India gives these castes a special advantage in terms of improving their upward socioeconomic mobility. OBC is another Indian population group recognized by constitution of India as “socially and educationally backward classes,” yet of higher status than SCs and STs.

Following the literature review of the previous section and based on the availability of data in the IHDS, we measured SES by the following variables:

-

1)

Literacy status of respondents’ parents (illiterate and literate)

-

2)

Caste of respondents (general castes, other backward castes, scheduled castes, and scheduled tribes)

-

3)

Religion of respondents divided into majority (Hindu) and non-majority (non-Hindu) religion

-

4)

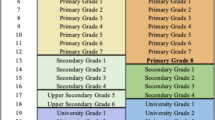

Educational attainment of respondents (illiterate, primary school, secondary school, and higher secondary and above)

-

5)

Per annum family income of respondents (less than 50,000 INRFootnote 2; 50,000–100,000 INR; and 100,000 INR or above)

Thus, all information refers to the SES of the ever-married women who were the respondents in the survey—except for the literacy status which refers directly to their parents. It is important to note that 95% of respondents said that their husbands’ caste was identical to their own. Nonetheless, to assure that respondents’ caste was the same as their parents’ caste, we restricted our analysis of mortality by caste to the data of those respondents with non-inter-caste marriagesFootnote 3.

Results

Sample description

Table 1 presents the sample description of the (female) respondents by age and parental survival status (IHDS data, 2011–2012). As to be expected, the percentage of respondents having a still living mother or father decreases with the age of the respondents. Moreover, the percentage of fathers still alive is lower than the percentage of still living mothers in all age groups. For instance, at age 45–49, half the respondents’ mothers are still alive compared to one-quarter of the respondents’ fathers.

Table 2 presents the share of respondent’s aged 15–49 with mother/father alive by socioeconomic indicators. The percentage of respondents with still living parents increases as the education level of the parents increases (illiterate mother 75.16%, literate mother 86.58%, illiterate father 51.02%, literate father 70.25%). Parental loss is more common among SC or ST respondents than among General or OBCs (e.g., for female, 79.09% respondents from general caste vs. 75.38 % from SC and ST). It is also observed that the proportion of parents alive is higher among mothers than among fathers. This is because husbands are typically older than their wives (see section 2.2.).

Similarly, parental survivorship among respondents that were not of the Hindu religion is slightly lower than among Hindu respondents. There is a clear positive gradient in parental survivorship when the education of the respondents rises from illiterate to higher secondary and above. The percentage of respondents belonging to the illiterate category with alive mother is about 1.24 times higher than that of respondents with at least higher-secondary education. By contrast, there is no substantial difference in maternal or paternal orphanhood by income level of the respondents’ family.

Consistency analysis of orphanhood estimates with SRS estimates

Table 3 compares life expectancy at age 15 (e15) estimated by the orphanhood method with official estimated from SRS, India. Note that while orphanhood estimates refer to a specific year, SRS estimates refer to a 5-year period (Table 3). Each of the orphanhood estimates is derived from the information about parental survival of respondents of a certain age. For females, the main inference from Table 3 is that e15 in 1998.5 obtained from the respondents aged 30–34 is higher than the estimates based on respondents aged 25–29 in 1999.6. These estimates (e15) obtained from respondents aged 30–34 are also higher than SRS estimates. Life expectancy estimates obtained from respondents aged 30–34 seem more reliable than from those aged 25–29 for theoretically.

Theoretically, orphanhood-based estimates of life expectancy should be higher than the estimates for the total population for several reasons (Luy 2012). Most importantly, orphanhood estimates refer exclusively to parous women and men (with surviving children) whose lower mortality compared to their nulliparous counterparts has been frequently described (e.g., Green et al. 1988; Doblhammer 2000; Hurt et al. 2006).

Moreover, childbearing occurs in India usually among married women and men. Previous literature documents that the mortality of married individuals is lower than that of non-married people because of health selection before marriage, healthier lifestyles during married life, and faster emergency help by the spouse when needed (Kaplan and Kronick 2006; Robards et al. 2012). Therefore, a higher estimate of e15 indicated an expected estimate in the Indian context.

Secondly, a downward trend in the estimates based on respondents aged under 30 suggested data from these ages is not representative to overall adult mortality, as it clearly contradicts the SRS trend. For both reasons, we infer SES disparity in female adult life expectancy obtained from the respondents aged 30–34. For the same reasons, we choose estimates for males based on respondents aged 25–34.

Adult mortality differential by socioeconomic status

Table 4 presents orphanhood estimates for females and males 40q30 (probability of deaths from age 30 to age 70 per 1000 persons) and e15 by SES for the period 1998–1999. The most significant finding in Table 4 is that mortality is substantially higher among disadvantaged groups, such as the illiterate, SC/ST, or non-Hindu population, and adults with less educated children (i.e., the respondents). The mortality ratio (40q30 of each category divided by 40q30 of reference category, as indicated in the table) for illiterate adults shows that 40q30 is higher than the corresponding rate for literate adults (females 3.2 times, males 1.6 times). On average, female adults belonging to SC/ST had a 1.6 times higher mortality rate than female adults belonging to the general caste. The difference in adult mortality by religious affiliation is negligible among men, but more distinct among women. The adult mortality differential by educational status of the respondents appears to be the greatest. As the education level of respondents increases, 40q30 among parents decreases. When we compare mortality differences by respondents’ literacy status (illiterate versus literate), we see a similar differential for both male and female adults.

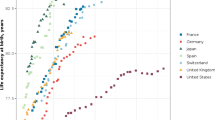

Table 4 and Fig. 1 present e15 by SES to illustrate these mortality differences in terms of life years after reaching adulthood (age 15). It is interesting to note that life expectancy is much higher among literates than illiterates (3.5 years for females and 5.7 years for males). The life expectancy differential is much smaller by caste or by religion. The indicator e15 increases sharply as the education of the respondents increases. Women who have offspring with high education have a 3.8-year-higher life expectancy than women with illiterate offspring. Among men, the corresponding difference is 4.6 years. The life expectancy of respondents’ parents also varies substantially by the respondents’ household income level. Adults with children in a high-income category live approximately 3 to 5 years longer than adults whose children have a low income.

Table 4 also shows adult mortality pattern by gender. Males experience higher mortality rate than female during their adulthood across all socio-economic subgroups. On average, females live one and half years longer than males (female 59.6, male 58.1) in the study period. The corresponding gap between female and male in SRS is about 3.1 years (females 56.3, males 53.2) (see Table 3).

Discussions and conclusion

Socioeconomic disparities in health and mortality have been of great concern to researchers and policymakers across the globe in recent decades. A person’s SES affects health through three important pathways, namely, health care, environmental exposure, and health behaviors (Adler and Newman 2002). At the same time, persistent stress associated with a lower SES also increases morbidity and mortality (Lazzarino et al. 2013). Though higher SES universally leads to lower adult mortality, studies for industrialized populations have shown that the magnitude of socioeconomic disparity varies immensely from one population to another (Caselli et al. 2017) or from one socioeconomic indicator to another within the same population (Luy et al. 2015). Although data are scarce, the same relationships and effects can be expected for developing countries. However, there may be differences with respect to the extent of these disparities, and also regarding which aspects of SES are the most relevant determinants of mortality differentials. In this paper, we have aimed to fill some of these knowledge gaps with regard to the population of India.

While there is a large literature on socioeconomic disparity in under-five mortality in India and other developing countries, lack of data on adult mortality led previous studies to focus on geographical differences in adult mortality. To the best of our knowledge, the present study provides the first empirical evidence of SES-specific disparities in adult life expectancy in India by applying an indirect estimation technique to a recent nationally representative survey data.

The findings of our study confirm that adult mortality varies markedly by SES measured both by adults’ own SES and the SES of their offspring. The most interesting finding of this investigation is that disparities in adult mortality appear to be highest in terms of the educational attainment of respondents or their children. Results show that being literate in India leads to an extended life expectancy of 4 to 6 years at early adulthood. This extent is consistent with previous studies conducted in advanced countries of the world (Luy et al. 2011; Murtin et al. 2017). A recent assessment of inequalities in longevity across education in 23 countries of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) reveals that, on average, the gap in life expectancy at age 25 between highly educated and poorly educated people is 8 years for men and 5 years for women (Murtin et al. 2017). Similarly, there is a substantial difference in adult mortality and corresponding life expectancy by educational attainment of children. This is because parents’ investment in the education of their offspring may yield significant returns for the parents themselves in later life (Friedman and Mare 2014; De Neve and Harling 2017). It may be also due to correlation between education of respondent and parent. Yet, it is found that the educational attainment of offspring has an independent effect on their parents’ mortality, even after controlling for parents’ own socioeconomic resources (Friedman and Mare 2014). It is worth to mention that education attainment of children has higher number of categories compared to other characteristics of the respondents or deceased.

The second largest disparity in adult mortality (40q30) appears by the income level of the married daughter’s family. Usually, Indian families adhere to a patriarchal ideology, follow the patrilineal rule of descent, and are patrilocal in nature. With the exception of a few tribes in Northeast India, daughters move to their husband’s house after marriage. There is therefore no reason to believe that parents’ survival status depends on the income level of a married daughter’s family. Yet, the economic condition of the married daughter’s family can be a proxy for a parent’s own economic condition because the majority of Indian marriages are either arranged marriages or marriages collectively decided by daughters and their parents with a focus on matching caste, income, education, food preferences, etc. (Allendorf and Pandian, 2016). Thus, the mortality differential by income level of a married daughter’s family may be the result of their own economic disparity. Both caste- and religion-based disparities in adult life expectancy are much lower than the disparity observed by level of education. This is consistent with the pattern observed in under-five mortality in India (IIPS and Macro 2007).

According to our results, adults belonging to the majority religion, namely Hindu, enjoy a marginally higher life expectancy than those belonging to a non-Hindu religion. This is in contrast to the religious differential observed in child mortality. Previous studies have shown that children belonging to the Hindu religion have higher mortality than children belonging to Islam, after controlling other socio-economic characteristics (IIPS and Macro 2007; Guillot et al. 2013). In this study, however, the non-Hindu sample includes adults from Islam, Christianity, Sikhism, and all other minority religions. It should be noted that all results presented in this study shows only gross differential in adult mortality by socio-economic characteristics. We could not estimate the life expectancy of social groups after controlling the effect of income or education.

Adult mortality estimates with the orphanhood method appear to be consistent with the official estimates provided by the Sample Registration System data. As seen in several studies in developing countries, indirect estimation techniques can provide robust mortality estimates when no reliable mortality statistics are available. Adding questions related to indirect demographic techniques in large surveys should be continued because they can provide important information about adult mortality at very low additional costs and efforts.

Naturally, the present study has some limitations. First, although the sample analyzed is nationally representative, the case numbers are still too low for a detailed analysis of each category. For instance, we have categorized education of the parents into only “illiterate” and “literate” because there were not enough adult women in middle or higher education categories. For the same reason, we cannot provide mortality estimates separately for scheduled castes and scheduled tribes. Secondly, as indirect estimation techniques provide retrospective estimates for a specific number of years before the survey was carried out. Our mortality estimates refer approximately to the period 1998–1999. Nonetheless, the estimates provided in this study are crucial, given that there were no efforts in past studies to understand adult mortality inequalities by SES. Thus, further studies could focus on whether the disparity has reduced or widened in the most recent period. There is also an additional uncertainty of e15 estimates as they are produced by extrapolating from mortality of middle-aged adults to mortality of adults of all ages. Thirdly, due to lack of information, we used constant mean age at child bearing for respondent’s characteristics (income and education). However, it was shown that the mortality estimates are not very sensitive to bias in this indicator (Moultrie et al. 2013). Finally, despite IHDS is a large sample survey representing the national population, the adult mortality rates presented here are representative only of adults with married daughters. We may therefore expect the mortality levels of the total population to be higher than those presented in this study. Nonetheless, this does not necessarily affect the estimated extent of differences in mortality by SES which was the main purpose of this study.

Notes

As IHDS data provides information on survival of the parents and parents-in-law of married women, we carried out an initial estimation of adult mortality using both sets of information. However, we did not observe any regular pattern in the estimates based on information about parents-in-law. This may be due to reporting bias on the survival of parents-in-law. We therefore restricted our analysis of adult mortality estimation to a respondent’s biological parents, rather than to her parents-in-law.

Approximately 76 INR equals to one euro.

Only about 5% of the total marriages are inter-caste marriages according to IHDS (2011–2012), and only 2.1% of marriages in India are inter-religious marriages, according to the National Family Health Survey (2005–2006) (IIPS and Macro, 2007). We can therefore assume the respondents’ caste and religion are the same as those of their parents.

References

Adler, N. E., & Newman, K. (2002). Socioeconomic disparities in health: pathways and policies. Health Affairs, 21(2), 60.

Allendorf, K., & Pandian, R. K. (2016). The decline of arranged marriage? Marital change and continuity in. India. Population and development review, 42(3), 435–464.

Ashenafi, W., Eshetu, F., Assefa, N., Oljira, L., Dedefo, M., Zelalem, D., et al. (2017). Trend and causes of adult mortality in Kersa health and demographic surveillance system (Kersa HDSS), eastern Ethiopia: verbal autopsy method. Population Health Metrics, 15(1), 22.

Barik, D., Desai, S., & Vanneman, R. (2018). Economic Status and Adult Mortality in India: Is the Relationship Sensitive to Choice of Indicators?. World development, 103, 176-187

Bhat, P. N. M. (1987). Mortality in India: levels, trends, and patterns. In A dissertation in demography. Ann Arbor: UMI.

Bhat, P. N. M. (1998). Demographic estimates for post-independence India: a new integration. Demography India, 27(1), 23–57.

Bicego, G. (1997). Estimating adult mortality rates in the context of the AIDS epidemic in sub-Saharan Africa: analysis of DHS sibling histories. Health Transition Review, 7(S2), 7–22.

Blacker, J. G. (1977). The estimation of adult mortality in Africa from data on orphanhood. Population Studies, 31(1), 107–128.

Bradshaw, D., & Timaeus, I. (2006). Levels and trends of adult mortality. In D. Jamison, R. Feachem, M. Makgoba, E. Bos, F. Baingana, K. Hofman, & K. Rogo (Eds.), Disease and mortality in Sub-Saharan Africa (pp. 31–42). Washington, DC: World Bank.

Brass, W., & Bamgboye, E. A. (1981). The time location of reports of survivorship: estimates for maternal and paternal orphanhood and the ever-widowed. Centre for Population Studies, Research Paper 81-1. London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine

Caldwell, J., & McDonald, P. (1982). Influence of maternal education on infant and child mortality: levels and causes. Health Policy and Education, 2(3–4), 251–267.

Case, A., & Deaton, A. (2015). Rising morbidity and mortality in midlife among white non-Hispanic Americans in the 21st century. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 112(49), 15078–15083.

Caselli, G., Drefahl, S., Wegner-Siegmundt, C., & Luy, M. (2017). Future mortality in low mortality countries (World Population and Human Capital in the Twenty-First Century: An Overview) (p. 5).

De Neve, J.-W., & Harling, G. (2017). Offspring schooling associated with increased parental survival in rural KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Social Science and Medicine, 176, 149–157.

De Walque, D., & Filmer, D. (2013). Trends and socioeconomic gradients in adult mortality around the developing world. Population and Development Review, 39(1), 1–29.

Doblhammer, G. (2000). Reproductive history and mortality later in life: a comparative study of England and Wales and Austria. Population Studies, 54(2), 169–176.

Dowd, J. B., & Todd, M. (2011). Does self-reported health bias the measurement of health inequalities in US adults? Evidence using anchoring vignettes from the Health and Retirement Study. Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 66(4), 478–489.

Friedman, E. M., & Mare, R. D. (2014). The schooling of offspring and the survival of parents. Demography, 51(4), 1271–1293.

Gakidou, E., & King, G. (2006). Death by survey: estimating adult mortality without selection bias from sibling survival data. Demography, 43(3), 569–585.

Galobardes, B., Shaw, M., Lawlor, D. A., Lynch, J. W., & Smith, G. D. (2006). Indicators of socioeconomic position (part 1). Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 60(1), 7–12.

Green, A., Beral, V., & Moser, K. (1988). Mortality in women in relation to their childbearing history. Bmj, 297(6645), 391–395.

Guillot, M., Gavrilova, N., Torgasheva, L., & Denisenko, M. (2013). Divergent paths for adult mortality in Russia and Central Asia: evidence from Kyrgyzstan. PLoS One, 8(10), e75314.

Hill, K., Zlotnik, H., & Trussell, J. (1983). Manual X (Indirect Techniques for Demographic Estimation). New York: United Nations.

Houweling, T. A., & Kunst, A. E. (2009). Socioeconomic inequalities in childhood mortality in low-and middle-income countries: a review of the international evidence. British Medical Bulletin, 93(1), 7–26.

Howe, L. D., Galobardes, B., Matijasevich, A., Gordon, D., Johnston, D., Onwujekwe, O., et al. (2012). Measuring socioeconomic position for epidemiological studies in low-and middle-income countries: a methods of measurement in epidemiology paper. International Journal of Epidemiology, 41(3), 871–886.

Hurt, L. S., Ronsmans, C., & Thomas, S. L. (2006). The effect of number of births on women’s mortality: systematic review of the evidence for women who have completed their childbearing. Population Studies, 60(1), 55–71.

IIPS, & Macro, O. R. C. (2007). National Family Health Survey (NFHS-3), 2005–2006. Mumbai: IIPS.

Joubert, J., Rao, C., Bradshaw, D., Vos, T., & Lopez, A. D. (2013). Evaluating the quality of national mortality statistics from civil registration in South Africa, 1997–2007. PLoS One, 8(5), e64592.

Kaplan, R. M., & Kronick, R. G. (2006). Marital status and longevity in the United States population. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 60(9), 760–765.

Krieger, N., Williams, D. R., & Moss, N. E. (1997). Measuring social class in US public health research: concepts, methodologies, and guidelines. Annual review of public health, 18(1), 341–378.

Krishnaji, N., & James, K. S. (2002). Gender differentials in adult mortality: with notes on rural-urban contrasts. Economic and Political Weekly, 37(46), 4633–4637.

Lazzarino, A. I., Hamer, M., Stamatakis, E., & Steptoe, A. (2013). Low socioeconomic status and psychological distress as synergistic predictors of mortality from stroke and coronary heart disease. Psychosomatic Medicine, 75(3), 311.

Luo, W., & Xie, Y. (2014). Socio-economic disparities in mortality among the elderly in China. Population Studies, 68(3), 305–320.

Luy, M. (2012). Estimating mortality differences in developed countries from survey information on maternal and paternal orphanhood. Demography, 49(2), 607–627.

Luy, M., Di Giulio, P., & Caselli, G. (2011). Differences in life expectancy by education and occupation in Italy, 1980–94: indirect estimates from maternal and paternal orphanhood. Population Studies, 65(2), 137–155.

Luy, M., Wegner-Siegmundt, C., Wiedemann, A., & Spijker, J. (2015). Life expectancy by education, income and occupation in Germany: estimations using the longitudinal survival method. Comparative Population Studies, 40(4), 399-436.

Lynch, J., & Kaplan, G. (2000). Socioeconomic position (Vol. 2000, pp. 13-35). Social epidemiology. New York: Oxford University Press.

Mackenbach, J. P., Bopp, M., Deboosere, P., Kovacs, K., Leinsalu, M., Martikainen, P., et al. (2017). Determinants of the magnitude of socioeconomic inequalities in mortality: a study of 17 European countries. Health and Place, 47, 44–53.

Malaker, C. R. (1986). Estimation of adult mortality in India: 1971–81. Demography India, 15(1), 126–136.

Moultrie, T. A., Dorrington, R. E., Hill, A. G., Hill, K., Timæus, I. M., & Zaba, B. (2013). Tools for demographic estimation: international union for the scientific study of population. Paris: International Union for the Scientific Study of Population.

Murtin, F., Mackenbach, J., Jasilionis, D., & d’Ercole, M. M. (2017). Inequalities in longevity by education in OECD countries: insights from new OECD estimates. OECD Statistics Working Paper No. 78. Paris: OECD Publishing.

Nikoi, C. A., & Odimegwu, C. (2013). The association between socioeconomic status and adult mortality in rural Kwazulu-Natal, South Africa. Oman Medical Journal, 28(2), 102.

Palloni, A., Massagli, M., & Marcotte, J. (1984). Estimating adult mortality with maternal orphanhood data: analysis of sensitivity of the techniques. Population Studies, 38(2), 255–279.

Ram, U., Jha, P., Gerland, P., Hum, R. J., Rodriguez, P., Suraweera, W., et al. (2015). Age-specific and sex-specific adult mortality risk in India in 2014: analysis of 0·27 million nationally surveyed deaths and demographic estimates from 597 districts. The Lancet Global Health, 3(12), e767–e775.

Robards, J., Evandrou, M., Falkingham, J., & Vlachantoni, A. (2012). Marital status, health and mortality. Maturitas, 73(4), 295–299.

Saikia, N., Jasilionis, D., Ram, F., & Shkolnikov, V. M. (2011). Trends and geographic differentials in mortality under age 60 in India. Population Studies, 65(1), 73–89.

Saikia, N., & Ram, F. (2010). Determinants of adult mortality in India. Asian Population Studies, 6(2), 153–171.

Saikia, N., Singh, A., & Ram, F. (2013). Adult male mortality in India: an application of the widowhood method. Asian Population Studies, 9(3), 244–263.

Schell, C. O., Reilly, M., Rosling, H., Peterson, S., & Mia Ekström, A. (2007). Socioeconomic determinants of infant mortality: a worldwide study of 152 low-, middle-, and high-income countries. Scandinavian Journal of Social Medicine, 35(3), 288–297.

Shavers, V. L. (2007). Measurement of socioeconomic status in health disparities research. Journal of the National Medical Association, 99(9), 1013.

Timaeus, I. (1991). Estimation of adult mortality from orphanhood before and since marriage. Population Studies, 45(3), 455–472.

Timæus, I. M., & Jasseh, M. (2004). Adult mortality in sub-Saharan Africa: evidence from Demographic and Health Surveys. Demography, 41(4), 757–772.

United Nations, Department of International Economic and Social Affairs. (1982). Model life tables for developing countries. New York: United Nations.

Vikram, K., Vanneman, R., & Desai, S. (2012). Linkages between maternal education and childhood immunization in India. Social Science and Medicine, 75(2), 331–339.

Wang, L. (2003). Determinants of child mortality in LDCs: empirical findings from demographic and health surveys. Health Policy, 65(3), 277–299.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the two anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments and criticisms which helped to improve the manuscript.

Funding

No funding was available for this study.

Availability of data and materials

All data are available publicly in the website https://www.icpsr.umich.edu/icpsrweb/DSDR/studies/22626

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

NS and ML conceptualized the paper. NS and JKB carried out the analysis. All authors interpreted and wrote the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional file

Additional file 1:

Mean age at childbearing by socio-economic status, India, 1981 (DOCX 17 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Saikia, N., Bora, J.K. & Luy, M. Socioeconomic disparity in adult mortality in India: estimations using the orphanhood method. Genus 75, 7 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41118-019-0054-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41118-019-0054-1