Abstract

Hypertension is very prevalent among patients undergoing dialysis therapy: hemodialysis (HD) and peritoneal dialysis (PD). Although it is recognized as a great risk of cardiovascular mortality for these populations, how to regulate blood pressure (BP) is poorly understood. For HD patients, we should pay much attention to methods of measuring BP. Out-of-center BP levels and BP variability should be evaluated by ambulatory BP monitoring and home BP measurement because they are closely associated with cardiovascular mortality. Although target BP levels are not clear, several clinical guidelines suggest <140/90 mmHg. However, it must be determined for each individual patient with careful considerations about comorbidities. Based on the underling pathophysiology of hypertension in patients on dialysis, maintaining an appropriate volume of body fluid by dietary salt restriction and optimization of dry weigh should be considered as a first line therapy. Inhibitors for renin-angiotensin system may be suitable to reduce BP and mortality for those patients on dialysis. These drugs may also be effective for preserving residual renal function and peritoneal function for PD patients. β-blockers may have potentials to improve survival for HD patients and can be added to anti-hypertensive medications. Lacking large-scale and good quality clinical trials, there are many questions to be answered. Much effort should continuously be made to create evidences for better management of hypertension for patients on dialysis therapy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Hypertension is very prevalent in patients undergoing dialysis therapy [1, 2]. As is for general population, it is one of the major causes of cardiovascular mortality for those who take dialysis [3]. It is still challenging to treat hypertension in patients on dialysis because there are many unsolved problems and concerns for the management of hypertension, mainly due to few good quality clinical trials. In this review, these problems will be discussed according to therapy types of dialysis: hemodialysis (HD) and peritoneal dialysis (PD).

Management of hypertension for patients on HD

Concerns about blood pressure (BP) measurement

It is of note that any standard methods to measure BP have not yet been established. Most of clinical studies have used pre-HD BP for determining optimal BP levels or analyzing the effects of BP-lowering therapies [4]. However, there is a great concern about when or how to measure BP [5]. A major determinant of blood pressure in HD patients is body fluid volume. Therefore, individual patient’s BP varies even during an HD session as well as between sessions [6]. This inconsistence is considered as a part of reasons why the association of BP levels and clinical outcomes has been controversial. Although conventional BP measurements during HD sessions is certainly important for the purpose of volume assessment and safety, we should consider other methods to evaluate patient’s BP such as ambulatory BP monitoring (ABPM) and home BP (HBP) measurements. These “out-of-dialysis-unit” BP measurements have shown to be superior to conventional BP measurements as they are linearly associated to the mortality of HD patients. For example, in a prospective cohort study, a 44-h ABP recording or 1-week HBP recording has more predictive power for target organ damage and mortality than conventional BP recordings [7]. Thus, it is recommended to measure BP with multiple methods in clinical guidelines such as by Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative (K/DOQI) and Japanese Society for Dialysis Therapy (JSDT) [8, 9].

Target BP levels

It has been shown that there is a “U-shape” relationship between BP and mortality by several observational studies [10–12] and a prospective cohort study [13], meaning that BP below certain levels is even more harmful than high levels. This reverse epidemiology of BP and cardiovascular mortality makes it difficult to determine target BP levels when treating hypertension. However, we should be cautious to interpret the results because low BP in these observational studies does not necessarily mean the consequence of anti-hypertensive treatment. In other words, patients with severe cardiovascular comorbidities may be included in those who have low BP, contributing to the poor prognosis. A multicenter prospective cohort study has recently reported interesting results about the relationship between all-cause mortality and systolic BP (SBP) [14]. In the study, there is a “U-shape” association to “dialysis-unit” SBP. In contrast, “out-of-dialysis-unit” SBP has a linear association to the mortality. These results suggest that optimal target BP for treatment should be determined by ABPM and HBP, although no such target has established yet.

As a target, the guidelines such as by K/DOQI and JSDT recommend BP less than 140/90 mmHg at the beginning of the week, with a caution not to apply uniformly to all patients [8, 9]. The caution includes how to reach the target BP. Aggressive approach to control BP can be a risk of symptomatic intradialytic hypotension, which is a great hazard for HD patients [15].

Nonpharmacological management of hypertension in HD patients

As mentioned earlier, BP in patients on HD depends on the volume of body fluid. Sodium and volume excess is the most important cause of hypertension. They are often observed when patients have low adherence to restrict dietary salt and water. High salt intake has been shown to associate with high pre-dialysis SBP and cardiovascular death [16]. It is thus a key to maintain proper body fluid volume to manage hypertension in HD patients. For this purpose, providing a patient education to reduce dietary salt should be the first line therapy. Salt consumption stimulates osmotic thirst and water drinking, leading to expand body fluid. Conversely, as far as salt restriction is successfully achieved, water appetite is minimized. Thus, guidelines such as by Kidney Disease/Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) and JSDT clearly state the importance of salt restriction [9, 17]. According to these guidelines, dietary salt should be restricted to below 5–6 g/day. Increase in fluid volume can be monitored by body weight, and interdialytic weight gain should not exceed 0.8 kg/day.

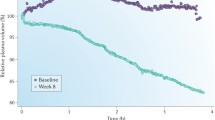

Another way to regulate the volume of body fluid is to set an appropriate dry weight (DW) for individual patient. In the dry-weight reduction in hypertensive hemodialysis patients (DRIP) trial, DW reduction by 1 kg at 8 weeks resulted in systolic and diastolic BP decrease by 6.6 and 3.3 mmHg, respectively [18]. This study clearly shows that the reduction of DW is a simple, efficacious, and well-tolerated maneuver to improve BP control. Despite the knowledge that to determine an appropriate DW is important for BP control, it is still challenging and sometimes needs “try and error.” Conventional ways to optimize DW utilize multiple parameters: physical signs of overhydration such as leg edema, cardio-thoracic ratio by chest X-ray, concentrations of serum natriuretic peptides, and so on. The problem is that these parameters are far from reliable. Recently, methods using bioimpedance analysis have been focused as reliable ways to estimate hydration status. Randomized control studies (RCTs) have demonstrated that optimization of DW by bioimpedance-guided methods are safe and capable of improving BP control [19, 20]. Thus, it is worthwhile applying these methods for DW setting.

Dialysis frequency also matters to BP regulation. The Frequent Hemodialysis Network Trial has compared the effect of a six-times-per-week dialysis regimen to the conventional three times weekly regimen [21]. As a result, the frequent HD significantly reduces BP. Another randomized cross-over study has demonstrated that short daily HD compared to conventional HD requires fewer anti-hypertensive medications to achieve the same BP [22]. These studies clearly show that frequent HD can improve BP control.

Hypoxemia by sleep apnea can be a cause of hypertension. In general population, obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is the frequent underlying disease of secondary hypertension and resistant hypertension [23]. It has been reported that patients with end-stage renal disease and with severe OSA are sevenfold more likely to have resistant hypertension than individuals in general hypertensive population [24]. Fluid overload is considered as a mechanism contributing to the pathogenesis of OSA in patients on dialysis [25]. Whether interventions to OSA can improve BP control and mortality is to be examined.

Treatment by anti-hypertensive drugs for HD patients

Most HD patients require anti-hypertensive drugs to control BP. Almost all patients have past history of hypertension before starting dialysis and have taken multiple anti-hypertensive medications. It has been reported by several cohort studies including JSDT registry [26] and meta-analyses [27, 28] that BP control by anti-hypertensive drugs leads to better cardiovascular outcomes. However, any optimal regimen to control BP and to reduce mortality has not yet been established.

Dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers (CCBs) are widely used to reduce BP for dialysis patients as well as general hypertensive population. They are effective for overhydrated state commonly observed in HD patients [29]. A randomized study demonstrated that amlodipine significantly reduced BP for subjects undergoing HD as compared with placebo [30]. Although there has been little evidence showing that CCBs reduce mortality, it is still considerable to add CCBs to anti-hypertensive medications.

Inhibitors of renin-angiotensin system (RAS) such as angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs) and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) have been widely used to reduce the cardiovascular mortality for chronic kidney disease (CKD) population as well as general population. As a consequence, most of patients have already been prescribed these RAS inhibitors before initiating dialysis therapy. Although no large scale RCTs have not yet been conducted, RAS inhibitors should be continued unless adverse effects are obvious. These agents are particularly beneficial for cardiac comorbidities generally seen in HD patients and have been effective for reducing left ventricular mass and mortality [31–34].

Hypertension and heart failure (HF) are the conditions frequently associated with CKD. In the pathophysiology of both conditions, sympathetic overactivity plays an important role [35]. With an ability to seize sympathetic activity, β-blockers may be suitable for treating both hypertension and HF in CKD [36]. A meta-analysis concluded that treatment with β-blockers improved all-cause mortality in patients with CKD and chronic HF [37]. They seem to be beneficial for HD patients as well. A retrospective cohort study analyzing the US Renal Data System (USRDS) has shown that β-blocker use was associated with a lower risk of new HF and cardiovascular mortality [38]. One prospective cohort study from Japan has also demonstrated that the use of β-blockers is significantly associated with reduced risk of mortality in HD patients [39]. Among β-blockers, there are many differences in pharmacological characteristics. Very recently, Weir and colleagues have provided a potentially important viewpoint regarding the dialyzability of β-blockers. They conducted a retrospective cohort study and found that “low-dialyzability” β-blockers are associated with lower mortality as compared with “high-dialyzability” β-blockers in elder HD patients [40]. Although not analyzed in Weir’s paper, carvedilol is one such β-blocker with “low-dialyzability.” It is the only β-blocker with evidence to reduce mortality rate in HD patients with dilated cardiomyopathy [41]. With these results, it can be a reasonable option to administrate potent β-blockers for HD patients to control BP.

Considerations for blood pressure variability (BPV)

There have been growing evidences showing that BPV is closely associated with worse outcomes in patients with hypertension [42–44]. BPV is also a great threat to patients on HD because they are always experiencing BP change in intra- and inter-HD sessions. It has been demonstrated that visit-to-visit BPV is extremely high in HD patients than non-HD populations and is a strong predictor for cardiovascular events [45]. Pre-dialysis systolic BPV is also associated with cardiovascular and all-cause mortality [46–48]. Not only pre-dialysis BPV but also intra- and post-dialysis BPV are related to adverse outcomes. A higher intradialytic BPV is independently associated with increased cardiovascular and all-cause mortality [49, 50]. Intradialytic BP rise is also a well-known complication of HD. Overhydration and activation of RAS and sympathetic nervous system are thought to underlie in the pathophysiology of this phenomenon [51]. It has been shown that an intra- or post-dialysis BP rise has been an independent predictor for cardiovascular death [52, 53]. Thus, it appears that BPV is a great risk of cardiovascular mortality for patients on HD. We should pay much attention not only to absolute BP values but also to pre- and inter-HD BPV. To detect and evaluate BPV, the importance of ABPM and HBP measurements is emphasized here again.

It becomes evident that BPV and cardiovascular damage are closely associated; however, whether there is causal relationship is still unclear. Among anti-hypertensive drugs, β-blockers or an antiadrenergic drug has been shown to abolish the excess risk for death and CV events associated with a high visit-to-visit SBP variability for CKD patients, not on HD [54]. This result suggests that BPV is indeed a cause of cardiovascular events and raises a hypothesis that these classes of drugs are effective to reduce BPV as well for patients undergoing HD. Nevertheless, clinical studies aiming to investigate whether any interventions to reduce BPV improve mortality will be needed.

Management of hypertension in patients on PD

Epidemiology

Hypertension in PD patients is as prevalent as in HD patients [55]. For BP evaluation, ABPM and HBP measurements are recommended because BP levels measured by these methods are closely associated with hypertensive end-organ damage such as left ventricular hypertrophy [56, 57]. A guideline published recently by International Society for Peritoneal Dialysis (ISPD) also recommends HBP measurement at least once a week [58]. As results from observational studies, relationship between BP and mortality is complex. One study showed that a SBP below 110 mmHg was associated with a high mortality [59]. Another study showed that a high BP was associated with a low mortality within the first year of PD initiation, then with a high mortality in the longer term [60]. There have been no RCTs to date to determine the optimal BP levels for PD patients. In the ISPD guideline [58], target BP below 140/90 mmHg is recommended based on data from general and CKD populations.

Nonpharmacological management of hypertension in PD patients

Salt and water excess is the most important determinant of raising BP in patients on PD [61, 62] as well as HD patients. It has been reported that hypervolemia evaluated by a bioimpedance analysis is indeed associated with high BP [62]. Conversely, dietary salt restriction contributes greatly to manage hypertension. A Turkish group has reported that a strict salt restriction (~4 g/day) significantly reduced BP and improved survival of the patients studied [63, 64]. Thus, as a first line strategy for BP management, dietary salt restriction is essential. ISPD guideline recommends salt restriction (<5 g/day) for all peritoneal dialysis patients unless contraindicated or patients show evidence of volume contraction or hypotension [58].

Considerations for residual renal function and peritoneal function

Residual renal function (RRF) has been shown to be an independent predictor for survival in dialysis patients including PD [65]. It becomes more difficult to maintain dialysis adequacy for PD patients as RRF declines. Therefore, preserving RRF is particularly important for patients on PD. For the purpose of RRF preservation, some strategies have been reported effective [66]. These include keeping proper body fluid volume and controlling BP. It has been widely accepted that RAS inhibition by ACEIs or ARBs is to be administrated to CKD patients because they have an ability to retard the rate of renal function loss [67]. RRF in PD patients can also be protected by these drugs as demonstrated by randomized clinical trials [68, 69]. Recently, a review by the Cochrane library concluded that ACEIs and ARBs have additional benefits of preserving RRF in patients on PD [70].

For patients on PD, peritoneal function is certainly important. Deterioration of peritoneal function has been characterized by neoangiogenesis and fibrosis. Among factors involved in this process, local RAS plays an important role [71]. All components of RAS can be produced locally in the peritoneal tissue and stimulate the signals leading to angiogenesiss and fibrosis [72]. In retrospective cohort studies, RAS inhibition was associated with the preservation of ultrafiltration and peritoneal transport rate [73–75], suggesting that administration of ACEIs or ARBs can be a way to slow the deterioration of peritoneal function.

As discussed above, RAS inhibition is beneficial for both preserving RRF and peritoneal function. One retrospective study suggested that use of ACEIs and ARBs improved the survival of PD patients [76]. Although high-quality evidence showing RAS inhibition for reduction of mortality does not exist [77], this strategy can be considered as a first line medication for hypertension in patients on PD.

Conclusions

Lacking large scale and good quality clinical trials, there are many questions to be answered. These include optimal methods to measure BP, target BP levels, appropriate regulations of body fluid volume, anti-hypertensive drugs to be used, and so on for patients on dialysis therapy. Currently, there is no means of treating hypertension with the best available knowledge, even if it is not perfect. But for the future, we should continue to make efforts to create better evidences about management of hypertension for those people.

References

Agarwal R, Nissenson AR, Batlle D, Coyne DW, Trout JR, Warnock DG. Prevalence, treatment, and control of hypertension in chronic hemodialysis patients in the United States. Am J Med. 2003;115(03):291–7. doi:10.1016/S0002-9343(03)00366-8.

Iseki K, Nakai S, Shinzato T, et al. Prevalence and determinants of hypertension in chronic hemodialysis patients in Japan. Ther Apher Dial. 2007;11(3):183–8. doi:10.1111/j.1744-9987.2007.00479.x.

Longenecker JC. Traditional cardiovascular disease risk factors in dialysis patients compared with the general population: the CHOICE study. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002;13:1918–27. doi:10.1097/01.ASN.0000019641.41496.1E.

Shafi T, Waheed S, Zager PG. Hypertension in hemodialysis patients: an opinion-based update. Semin Dial. 2014;27(2):146–53. doi:10.1111/sdi.12195.

Roberts M, Pilmore HL, Tonkin AM, et al. Challenges in blood pressure measurement in patients treated with maintenance hemodialysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2012;60(3):463–72. doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2012.04.026.

Kuipers J, Usvyat L a, Oosterhuis JK, et al. Variability of predialytic, intradialytic, and postdialytic blood pressures in the course of a week: a study of Dutch and US maintenance hemodialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2013;62(4):779–88. doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2013.03.034.

Agarwal R, Andersen MJ, Light RP. Location not quantity of blood pressure measurements predicts mortality in hemodialysis patients. Am J Nephrol. 2008;28(2):210–7. doi:10.1159/000110090.

K/DOQI. K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for cardiovascular disease in dialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2005;45(4):16–153. doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2005.01.019.

Hirakata H, Nitta K, Inaba M, et al. Japanese Society for Dialysis Therapy guidelines for management of cardiovascular diseases in patients on chronic hemodialysis. Ther Apher Dial. 2012;16(5):387–435. doi:10.1111/j.1744-9987.2012.01088.x.

Mc Causland FR, Waikar SS, Brunelli SM, et al. Reverse epidemiology of hypertension and cardiovascular death in the hemodialysis population: the 58th annual fall conference and scientific sessions. Nephron Clin Pr. 2009;113(3):62–8. doi:10.1681/ASN.2012080777.

Inaba M, Karaboyas A, Akiba T, et al. Association of blood pressure with all-cause mortality and stroke in Japanese hemodialysis patients: the Japan dialysis outcomes and practice pattern study. Hemodial Int. 2014;18(3):607–15. doi:10.1111/hdi.12156.

Carney EF. Dialysis: U-shaped associations between changes in blood pressure during dialysis and patient survival. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2013;9(8):431. doi:10.1038/nrneph.2013.112.

Robinson BM, Tong L, Zhang J, et al. Blood pressure levels and mortality risk among hemodialysis patients in the Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study. Kidney Int. 2012;82(5):570–80. doi:10.1038/ki.2012.136.

Bansal N, McCulloch CE, Rahman M, et al. Blood pressure and risk of all-cause mortality in advanced chronic kidney disease and hemodialysis: the chronic renal insufficiency cohort study. Hypertension. 2015;65(1):93–100. doi:10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.114.04334.

Davenport A, Cox C, Thuraisingham R. Achieving blood pressure targets during dialysis improves control but increases intradialytic hypotension. Kidney Int. 2008;73(6):759–64. doi:10.1038/sj.ki.5002745.

Mc Causland FR, Waikar SS, Brunelli SM. Increased dietary sodium is independently associated with greater mortality among prevalent hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int. 2012;82(2):204–11. doi:10.1038/ki.2012.42.

Levin NW, Kotanko P, Eckardt K-U, et al. Blood pressure in chronic kidney disease stage 5D-report from a kidney disease: improving global outcomes controversies conference. Kidney Int. 2010;77(4):273–84. doi:10.1038/ki.2009.469.

Agarwal R, Alborzi P, Satyan S, Light RP. Dry-weight reduction in hypertensive hemodialysis patients (DRIP): a randomized, controlled trial. Hypertension. 2009;53(3):500–7. doi:10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.125674.

Moissl U, Arias-Guillén M, Wabel P, et al. Bioimpedance-guided fluid management in hemodialysis patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;8(9):1575–82. doi:10.2215/CJN.12411212.

Onofriescu M, Hogas S, Voroneanu L, et al. Bioimpedance-guided fluid management in maintenance hemodialysis: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Am J Kidney Dis. 2014;64(1):111–8. doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2014.01.420.

Group TFT. In-center hemodialysis six times per week versus three times per week. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:2287–300.

Zimmerman DL, Ruzicka M, Hebert P, Fergusson D, Touyz RM, Burns KD. Short daily versus conventional hemodialysis for hypertensive patients: a randomized cross-over study. PLoS One. 2014;9(5):1–8. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0097135.

Kario K. Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome and hypertension: ambulatory blood pressure. Hypertens Res. 2009;32(6):428–32. doi:10.1038/hr.2009.56.

Abdel-Kadera K, Doharb S, Shaha N, et al. Resistant hypertension and obstructive sleep apnea in the setting of kidney disease. J Hypertens. 2012;30(5):960–6. doi:10.1097/HJH.0b013e328351d08a.

Lyons O, Chan C, Yadollahi A, Bradley T. Effect of ultrafiltration on sleep apnea and sleep structure in patients with end-stage renal disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;191(11):1287–94. doi:10.1164/rccm.201412-2288OC.

Iseki K, Shoji T, Nakai S, Watanabe Y, Akiba T, Tsubakihara Y. Higher survival rates of chronic hemodialysis patients on anti-hypertensive drugs. Nephron Clin Pr. 2009;113(3):c183–90. doi:10.1159/000232600.

Heerspink HJL, Ninomiya T, Zoungas S, et al. Effect of lowering blood pressure on cardiovascular events and mortality in patients on dialysis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Lancet. 2009;373(9668):1009–15. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60212-9.

Agarwal R, Sinha AD. Cardiovascular protection with antihypertensive drugs in dialysis patients: systematic review and meta-analysis. Hypertension. 2009;53(5):860–6. doi:10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.128116.

London GM, Marchais SJ, Guerin AP, et al. Salt and water retention and calcium blockade in uremia. Circulation. 1990;82(1):105–13. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2364508.

Tepel M, Hopfenmueller W, Scholze A, Maier A, Zidek W. Effect of amlodipine on cardiovascular events in hypertensive haemodialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2008;23(11):3605–12. doi:10.1093/ndt/gfn304.

Takahashi A, Takase H, Toriyama T, et al. Candesartan, an angiotensin II type-1 receptor blocker, reduces cardiovascular events in patients on chronic haemodialysis—a randomized study. Nephrol Dial Transpl. 2006;21(June):2507–12. doi:10.1093/ndt/gfl293.

Efrati S, Zaidenstein R, Dishy V, et al. ACE inhibitors and survival of hemodialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2002;40(5):1023–9. doi:10.1053/ajkd.2002.36340.

Matsumoto N, Ishimitsu T, Okamura A, Seta H, Takahashi M, Matsuoka H. Effects of imidapril on left ventricular mass in chronic hemodialysis patients. Hypertens Res. 2006;29(4):253–60.

Messa P, Cannella G. Left ventricular geometry and adverse cardiovascular events in chronic hemodialysis patients on prolonged therapy with ACE inhibitors. Am J Kidney Dis. 2002;40(4):728–36. doi:10.1053/ajkd.2002.35680.

Klein IHHT. Sympathetic nerve activity is inappropriately increased in chronic renal disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2003;14(12):3239–44. doi:10.1097/01.ASN.0000098687.01005.A5.

Bakris GL, Hart P, Ritz E. Beta blockers in the management of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2006;70:1905–13. doi:10.1038/sj.ki.5001835.

Badve SV, Roberts M a, Hawley CM, et al. Effects of beta-adrenergic antagonists in patients with chronic kidney disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58(11):1152–61. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2011.04.041.

Kevin CA, Fernando CT, Lawrence YA, Allen JT, George LB. Beta-blocker use in long-term dialysis patients. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:2465–71.

Nakao K, Makino H, Morita S, et al. Beta-blocker prescription and outcomes in hemodialysis patients from the Japan Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study. Nephron Clin Pr. 2009;113(3):c132–9. doi:10.1159/000232593.

Weir MA, Dixon SN, Fleet JL, et al. Beta-blocker dialyzability and mortality in older patients receiving hemodialysis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;26:987–96. doi:10.1681/ASN.2014040324.

Cice G, Ferrara L, D’Andrea A, et al. Carvedilol increases two-year survival in dialysis patients with dilated cardiomyopathy: a prospective, placebo-controlled trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;41(9):1438–44. doi:10.1016/S0735-1097(03)00241-9.

Kikuya M, Hozawa A, Ohkubo T, et al. Prognostic significance of blood pressure and heart rate variabilities: the Ohasama study. Hypertension. 2000;36:901–6.

Pringle E, Phillips C, Thijs L, et al. Systolic blood pressure variability as a risk factor for stroke and cardiovascular mortality in the elderly hypertensive population. J Hypertens. 2003;21(12):2251–7. doi:10.1097/01.hjh.0000098144.70956.0f.

Rothwell PM, Howard SC, Dolan E, et al. Prognostic significance of visit-to-visit variability, maximum systolic blood pressure, and episodic hypertension. Lancet. 2010;375(9718):895–905. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60308-X.

Rossignol P, Cridlig J, Lehert P, Kessler M, Zannad F. Visit-to-visit blood pressure variability is a strong predictor of cardiovascular events in hemodialysis: insights from FOSIDIAL. Hypertension. 2012;60(2):339–46. doi:10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.190397.

Shafi T, Sozio SM, Bandeen-Roche KJ, et al. Predialysis systolic BP variability and outcomes in hemodialysis patients. Jasn. 2014:1–11. doi:10.1681/ASN.2013060667

Selvarajah V, Pasea L, Ojha S, Wilkinson IB, Tomlinson LA. Pre-dialysis systolic blood pressure-variability is independently associated with all-cause mortality in incident haemodialysis patients. PLoS One. 2014;9(1), e86514. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0086514.

Chang TI, Flythe JE, Brunelli SM, et al. Visit-to-visit systolic blood pressure variability and outcomes in hemodialysis. J Hum Hypertens. 2014;28(1):18–24. doi:10.1038/jhh.2013.49.

Flythe JE, Inrig JK, Shafi T, et al. Association of intradialytic blood pressure variability with increased all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in patients treated with long-term hemodialysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2013;61(6):966–74. doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2012.12.023.

Park J, Rhee CM, Sim JJ, et al. A comparative effectiveness research study of the change in blood pressure during hemodialysis treatment and survival. Kidney Int. 2013;84(4):795–802. doi:10.1038/ki.2013.237.

Georgianos PI, Sarafidis PA, Zoccali C. Intradialysis hypertension in end-stage renal disease patients. Hypertension. 2015;66(3):456–63. doi:10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.115.05858.

Inrig JK, Oddone EZ, Hasselblad V, et al. Association of intradialytic blood pressure changes with hospitalization and mortality rates in prevalent ESRD patients. Kidney Int. 2007;71(5):454–61. doi:10.1038/sj.ki.5002077.

Yang C, Yang W, Lin Y. Postdialysis blood pressure rise predicts long-term outcomes in chronic hemodialysis patients: a four-year prospective observational cohort study. BMC Nephrol. 2012;13:12.

Mallamaci F, Minutolo R, Leonardis D, et al. Long-term visit-to-visit office blood pressure variability increases the risk of adverse cardiovascular outcomes in patients with chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2013;84(2):381–9. doi:10.1038/ki.2013.132.

Ortega LM, Materson BJ. Hypertension in peritoneal dialysis patients: epidemiology, pathogenesis, and treatment. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2011;5(3):128–36. doi:10.1016/j.jash.2011.02.004.

Cheigh JS, Kim H. Hypertension in continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis patients: what do we know and what can we do about it? Perit Dial Int. 1999;19 Suppl 2:S138–43. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10406508.

Terawaki H, Shoda T, Ogura M, et al. Morning hypertension determined by self-measurement at home predicts left ventricular hypertrophy in patients undergoing continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis. Ther Apher Dial. 2012;16(3):260–6. doi:10.1111/j.1744-9987.2012.01059.x.

Kang S, Kooman JP, Lambie M, Mcintyre C, Mehrotra R. ISPD cardiovascular and metabolic guidelines in adult peritoneal dialysis patients part I—assessment and management of various cardiovascular risk factors. Perit Dial Int. 2015;35(3):1–9. doi:10.3747/pdi.2014.00279.

Goldfarb-Rumyantzev AS, Baird BC, Leypoldt JK, Cheung AK. The association between BP and mortality in patients on chronic peritoneal dialysis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2005;20(8):1693–701. doi:10.1093/ndt/gfh856.

Udayaraj UP, Steenkamp R, Caskey FJ, et al. Blood pressure and mortality risk on peritoneal dialysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2009;53(1):70–8. doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2008.08.030.

Wang X, Axelsson J, Lindholm B, Wang T. Volume status and blood pressure in continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis patients. Blood Purif. 2005;23(5):373–8. doi:10.1159/000087194.

Chen W, Cheng LT, Wang T. Salt and fluid intake in the development of hypertension in peritoneal dialysis patients. Ren Fail. 2007;29(4):427–32. doi:10.1080/08860220701260461.

Gunal AI, Duman S, Ozkahya M, et al. Strict volume control normalizes hypertension in peritoneal dialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2001;37(3):588–93. doi:10.1053/ajkd.2001.22085.

Kircelli F, Asci G, Yilmaz M, et al. The impact of strict volume control strategy on patient survival and technique failure in peritoneal dialysis patients. Blood Purif. 2011;32(1):30–7. doi:10.1159/000323038.

Perl J, Bargman JM. The importance of residual kidney function for patients on dialysis: a critical review. Am J Kidney Dis. 2009;53(6):1068–81. doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2009.02.012.

Nongnuch A, Assanatham M, Panorchan K, Davenport A. Strategies for preserving residual renal function in peritoneal dialysis patients. Clin Kidney J. 2015;8(2):202–11. doi:10.1093/ckj/sfu140.

Casas JP, Chua W, Loukogeorgakis S, et al. Effect of inhibitors of the renin-angiotensin system and other antihypertensive drugs on renal outcomes: systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2005;366(9502):2026–33. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67814-2.

Li PK-T, Chow K, Wong TY-H. Effects of an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor on residual renal function in patients receiving peritoneal dialysis. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139:105–12. Available at: http://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&btnG=Search&q=intitle:Effects+of+an+Angiotensin-Converting+Enzyme+Inhibitor+on+Residual+Renal+Function+in+Patients+Receiving+Peritoneal+Dialysis#1.

Suzuki H, Kanno Y, Sugahara S, Okada H, Nakamoto H. Effects of an angiotensin II receptor blocker, valsartan, on residual renal function in patients on CAPD. Am J Kidney Dis. 2004;43(6):1056–64. doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2004.01.019.

Zhang L, Zeng X, Fu P, Hm W, Wu HM. Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor blockers for preserving residual kidney function in peritoneal dialysis patients (protocol). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;6.

Nessim SJ, Perl J, Bargman JM. The renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system in peritoneal dialysis: is what is good for the kidney also good for the peritoneum? Kidney Int. 2010;78(1):23–8. doi:10.1038/ki.2010.90.

Pletinck A, Vanholder R, Veys N, Van Biesen W. Protecting the peritoneal membrane: factors beyond peritoneal dialysis solutions. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2012;8(9):542–50. doi:10.1038/nrneph.2012.144.

Trošt Rupnik A, Pajek J, Guček A, et al. Influence of renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system-blocking drugs on peritoneal membrane in peritoneal dialysis patients. Ther Apher Dial. 2013;17(4):425–30. doi:10.1111/1744-9987.12091.

Jing S, Kezhou Y, Hong Z, Qun W, Rong W. Effect of renin-angiotensin system inhibitors on prevention of peritoneal fibrosis in peritoneal dialysis patients. Nephrology (Carlton). 2010;15(1):27–32. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1797.2009.01162.x.

Kolesnyk I, Noordzij M, Dekker FW, Boeschoten EW, Krediet RT. A positive effect of AII inhibitors on peritoneal membrane function in long-term PD patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2009;24(1):272–7. doi:10.1093/ndt/gfn421.

Fang W, Oreopoulos DG, Bargman JM. Use of ACE inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers and survival in patients on peritoneal dialysis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2008;23(11):3704–10. doi:10.1093/ndt/gfn321.

Akbari G, Ferguson D, McCormick B, Davis A, Biyani MAK. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers in peritoneal dialysis: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Perit Dial Int. 2009;29(5):554–61.

Acknowledgement

The author thanks Ms. Kumiko Shiota and Kaori Yoshida for their excellent secretarial assistance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The author declares that he has no competing interests.

Author’s contributions

YT wrote the entire manuscript and approved it.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Taniyama, Y. Management of hypertension for patients undergoing dialysis therapy. Ren Replace Ther 2, 21 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41100-016-0034-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41100-016-0034-2