Abstract

Background

Antidiabetic medication adherence is a key aspect for successful control of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). This systematic review aims to provide an overview of the associations between socioeconomic factors and antidiabetic medication adherence in individuals with T2DM.

Methods

A study protocol was established using the PRISMA checklist. A primary literature search was conducted during March 2022, searching PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, as well as WorldCat and the Bielefeld Academic Search Engine. Studies were included if published between 1990 and 2022 and included individuals with T2DM. During primary screening, one reviewer screened titles and abstracts for eligibility, while in the secondary screening, two reviewers worked independently to extract the relevant data from the full-text articles.

Results

A total of 15,128 studies were found in the primary search, and 102 were finally included in the review. Most studies found were cross-sectional (72) and many investigated multiple socioeconomic factors. Four subcategories of socioeconomic factors were identified: economic (70), social (74), ethnical/racial (19) and geographical (18). The majority of studies found an association with antidiabetic medication adherence for two specific factors, namely individuals’ insurance status (10) and ethnicity or race (18). Other important factors were income and education.

Conclusions

A large heterogeneity between studies was observed, with many studies relying on subjective data from interviewed individuals with a potential for recall bias. Several socioeconomic groups influencing medication adherence were identified, suggesting potential areas of intervention for the improvement of diabetes treatment adherence and individuals’ long-term well-being.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

According to the International Diabetes Federation, the diabetes mellitus epidemic affected about 537 million adults aged 20–79 years worldwide in 2021 and about 90% of all diabetes cases are considered to be type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) cases [1]. The number is predicted to rise to 643 million by 2030 and 783 million by 2045, with the largest proportion based in low- to middle-income countries [1]. Among the causes of this rapidly growing epidemic, there are population ageing, economic advances, rise of obesity and sedentary lifestyle, as well as excessive consumption of sugar and fat [2, 3].

Adequate treatment of the disease is of great importance, as uncontrolled T2DM is strongly associated with cardiovascular risk factors, the number one cause of death for individuals with T2DM, contributing to the dysmetabolic syndrome [4]. Uncontrolled T2DM can also lead to diabetic kidney disease [5], diabetic retinopathy, neuropathy and an increased risk for periodontitis [1].

Therapeutic approaches are highly individualized and based on the severity of the disease, the estimated life expectancy and comorbidities [6,7,8,9]. An essential indicator of T2DM severity and efficacy of treatment is the glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) value [10]. Initial recommendations for reaching and maintaining a target HbA1c value include lifestyle modifications such as reducing sedentary lifestyle, increasing physical activity, smoking cessation, reduction in the alcohol consumption and, most importantly, reduction in the obesity and diet adjustments. If these changes do not suffice, medication treatment is recommended, starting with medications without risk of hypoglycaemia, followed by medication with risk of hypoglycaemia, up to administration of insulin [6,7,8,9].

Adherence to recommended medications plays a key role for a successful treatment strategy in terms of efficacy. Poor medication adherence is encountered frequently and is highly associated with increased morbidity, mortality, higher costs and more hospitalizations [11,12,13,14,15,16,17], and it may be affected by socioeconomic and demographic factors influencing individuals’ lives. A review looking at the association between ethnicities and migration background and non-adherence was conducted in 2009, but led to inconclusive results as the number of included studies was too small and differences in study conduction were substantial [18]. More recent studies focused on developing nations [19], low- to middle-income countries [20] or Asian countries [17]. A positive association between education and adherence was found in some studies [17, 20], while others found an association with non-adherence for both employed and individuals with low income [20]. In contrast, another review found that employment is not associated with a difference in adherence [17].

The inconsistences of earlier findings and the lack of more comprehensive reviews call for a systematic review aiming to provide a global perspective of the relationships between antidiabetic medication adherence and socioeconomic factors in individuals affected by T2DM. Specifically, socioeconomic factors of interest are all social determinants of health as defined by the World Health Organization which include all non-medical factors influencing health outcomes such as medication adherence. The current review proposes an up-to-date overview of the research conducted on the topic and related findings, and provides a classification of the results and the direction of the findings based on two major groups of socioeconomic factors (economic/social and ethnical/geographical). Finally, it aims to support practitioners to identify vulnerable populations of patients and needs for interventions and further research.

Materials and methods

The study aimed to retrieve all available evidence on the associations between socioeconomic factors and antidiabetic medication adherence in individuals with T2DM. Factors included in the literature review may have heterogeneous naming, definitions and categorizations, and the reporting of the results was based on an overall classification of socioeconomic factors, which divides them into economic/social or ethnical/geographical.

Additionally, medication use in published articles was referred to using terms such as ‘adherence’, ‘compliance’, ‘concordance’ and ‘persistence’. Some of these terms are used inconsistently or often interchangeably and are also dependent on the study design [14, 21, 22]. In this systematic review, adherence was used as an umbrella term according to Vries et al. (2012) and defined as a combination of a patient’s medication initiation, implementation, persistence and discontinuation [14].

A study protocol was established following the PRISMA checklist. A literature search was conducted using the major online databases containing biomedical and life sciences literature, namely PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, as well as on the grey/unpublished literature databases WorldCat and the Bielefeld Academic Search Engine (BASE). Free-text terms used for the search consisted of three main blocks: (diabetes mellitus type 2) AND (socioeconomic factors) AND (medication adherence). A full list of terms can be found in Supplementary Material, Appendix 1. Multiple synonyms and variations were used to supplement the main keywords to increase the probability of retrieving relevant articles. Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) terms and Emtree were utilized for labelled articles search. The systematic review included original articles investigating the association between socioeconomic factors and antidiabetic medication use in individuals with T2DM published in English between 1 January 1990 and the extraction date, 15 March 2022. Articles excluded were case studies/series, as well as literature reviews, and articles that did not clearly state whether the population was including individuals with T2DM.

All articles identified from the major online databases and the grey literature were extracted into a single EndNote library. EndNote was used to automatically remove duplicates while the remaining articles were manually screened. Titles and abstracts of the articles were primarily screened for eligibility by a first reviewer. In case of uncertainties, a second reviewer examined the articles to verify eligibility for the secondary screening. Additional articles were manually selected by the first reviewer, screening original articles and literature reviews found during the primary screening. Finally, the articles included in the secondary screening were searched for additional references.

The secondary screening was conducted in parallel and independently by the two reviewers. The full text was evaluated, and prespecified information was extracted including study design, type of data collection, definition of adherence used, type of medication (insulin/oral antidiabetic), socioeconomic factors influencing adherence, the direction of the association, study period, geographical setting, number of participants, special subpopulations studied and a quality assessment. The National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute of Health (NHLBI) quality assessment tool [23] was used since it is suitable for the evaluation of both experimental and observational studies. In case of inconsistencies in the data extraction, the two reviewers elaborated their points, and when no common ground could be found, a third reviewer was consulted to reach a final assessment.

The results from the systematic review were categorized into economic/social and ethnical/geographical factors, and within these two groups, factors were classified into additional main domains and subgroups. Finally, the included studies were grouped based on the direction of the reported associations between socioeconomic factors and antidiabetic medication adherence (increase, no association, decrease), and study design.

Results

The primary screening, in which only the title and the abstract of the articles were considered, was conducted by the first reviewer, and the complete PRISMA flowchart of the studies included/excluded is shown in Fig. 1. A total of 15,128 articles were retrieved from searching the different online databases. After automated removal of duplicates, 11,979 articles were left for primary manual screening, and after that, 186 articles remained eligible for the secondary screening conducted independently by the two reviewers.

PRISMA flowchart of the included studies [120].

In the secondary full-text screening, 102 articles were found to be eligible. The reasons for exclusion were that the articles were not T2DM-specific (n = 48), the studies were conducted using an excluded study design (n = 7), no socioeconomic factors were investigated (n = 10), only self-perceived factors were investigated (n = 5), adherence was not an outcome (n = 5), adherence differences between antidiabetic medication types were investigated (n = 2), or the studies were not on topic for other reasons (n = 4). Additionally, during the full-text screening 8 articles were not accessible, 1 article was retracted, 2 articles were not available in English, and 1 article was a duplicate.

In total, 73 of the articles included had a cross-sectional study design, 23 were cohort studies, 5 were experimental and 1 was a case–control study. Categorized by continent where the study was conducted, a total of 15 studies were in Africa, 42 in Asia, 4 in South America, 1 in Central America, 29 in North America, 5 in Europe and 6 in Oceania. In total, 67 studies were identified with fewer than 500 participants, 18 studies with more than 500 participants but less than 5000 and 17 studies with more than 5000 participants. A total of 72 studies looked at all types of medication used in T2DM, 26 studies investigated individuals using oral antidiabetic medication and 4 studies investigated individuals using insulin. Utilizing the NHLBI quality assessment tool [23] led to 25 studies rated as good, 53 studies rated as fair and 24 studies rated as poor.

Economic and social factors

A total of 70 studies investigated associations between medication adherence and one or more economic factors, while a total of 74 studies investigated social factors. The complete results with all references are given in Table 1 where the studies are reported by type of socioeconomic factor investigated, study design and direction of the association assessed (increase, no association, decrease).

Socioeconomic status and occupational status

Three studies conducted in Asia [24,25,26] and 1 conducted in Egypt [27] concluded that the socioeconomic status of an individual is positively associated with medication adherence. In contrast, 7 Asian studies [28,29,30,31,32,33,34] and 1 study from New Zealand [35] did not find any difference in adherence. Two studies conducted in Japan [52] and Germany [53] concluded that employed individuals were less likely to be adherent than non-employed individuals. Three studies from Libya [54], Ghana [55] and Nigeria [56] investigating the association between unemployment and adherence showed results in different directions. Retirement was associated with decreased adherence in a Malaysian [57] study, while stay-at-home housewives were more likely to be adherent to their medication, according to an Indian study [58]. A total of 18 studies did not find any association between occupation and medication adherence [25, 32, 36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51].

Income and housing type

Five Asian studies [42, 52, 61,62,63] as well as 4 studies from the USA [59, 60, 64, 65] found a positive association between income and medication adherence. Opposing this trend, a single Malaysian study [73] found a negative association between higher income and medication adherence, while 15 studies across the globe found no association in either direction [25, 37, 41, 44, 46, 51, 54, 58, 66,67,68,69,70,71,72]. An Indian study found a negative association between individuals being paid on a daily basis and their adherence to medication [31]. Six studies [74,75,76,77,78,79] found that individuals going through financial hardship were less likely to adhere to their medication regimen. Two studies conducted in Africa [67, 81] also found a negative association between higher medication cost and adherence, whereas a Papua New Guinean study found no association [80]. A US study found that homeless individuals were less likely to be adherent [83], while an Iranian study did not find any difference in adherence between homeowners and non-homeowners [45]. ‘Housing status’ was found to be associated with decreased adherence in a Sudanese study [82]; however, the study did not clearly define the term ‘housing status’.

Insurance status, economic support and transportation availability

Ten US studies found that individuals were less likely to be adherent when they had no insurance [65, 87, 89], had a capitated health plan [90], or were registered with Medicaid [77, 86,87,88] and Medicare [86, 88]. Also, higher co-payments were associated with less adherence in 5 US studies and 1 study conducted in Bosnia and Herzegovina [50, 65, 92,93,94,95]. Likewise, commercial insurance [58] and having health coverage [51] were associated with increased adherence in 2 US studies. In other countries, a similar trend was observed, i.e. having no insurance was associated with lower adherence in 3 studies conducted in Iran [45], Nigeria [67] and Mexico [76], while commercially insured individuals in Israel [91] and in the United Arab Emirates [42] were more likely to adhere to their medication plan. Individuals with T2DM receiving social security were less likely to be adherent according to 1 US study [71], as well as individuals relying on economic support provided by relatives in 1 Mexican study [76]. Transportation availability was not associated with a change in adherence in 1 study conducted in the United Arab Emirates [36].

Civil status and living arrangement

Five studies from different countries concluded that married individuals are more likely to be adherent to their medication [27, 53, 56, 101, 102]. Matching these results, 1 Iranian study reported lower adherence in divorced and widowed individuals [103] and 2 US studies reported less adherence for single individuals [71, 104]. One Brazilian study opposes these findings, reporting an association between married individuals and decreased adherence [70]. However, a total of 21 studies did not find any association between civil status and medication adherence [25, 29, 31, 36, 37, 39, 42, 45, 48, 50, 54, 62, 66, 75, 82, 83, 96,97,98,99,100], the majority conducted in Asia [25, 29, 31, 36, 42, 45, 54, 62, 75, 98,99,100] and Africa [37, 48, 82, 97, 115].

One Israeli study found that smaller family size was associated with higher medication adherence [91], 1 Iranian study concluded that individuals living alone were more likely to adhere to their medication regimen [45], and 4 Asian [30, 36, 52, 106] and 1 African study [105] did not find any association between living arrangement and medication adherence.

Education

Higher education was associated with higher adherence in 17 studies [24, 26, 27, 36, 38, 41, 42, 53, 55, 63, 64, 91, 100, 102, 115,116,117], of which 11 were conducted in Asia [24, 26, 36, 41, 42, 63, 91, 100, 102, 116, 117], 4 in Africa [27, 38, 55, 115], 1 in Europe [53] and 1 in the USA [64]. One study conducted in the USA found that higher education only had a positive association with adherence when the patient had an immigrant background [85]. Three studies from Iran [100], India [62] and Ghana [48] concluded that illiterate individuals were less likely to be adherent. One Cameroonian study found a negative association between higher education and adherence [74]. The majority [39] of the studies including education did not find any association between this factor and adherence [25, 28, 30, 31, 37, 43,44,45,46,47, 49,50,51,52, 54, 56, 59,60,61, 67, 70,71,72,73, 75, 81, 82, 85, 97, 98, 101, 106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114]. Twenty-two of these studies were conducted in Asia [25, 28, 30, 31, 43,44,45,46,47, 49, 52, 54, 61, 73, 75, 98, 101, 106, 107, 111, 113, 114], 6 in Africa [37, 56, 67, 81, 82, 97], 6 in the USA [51, 59, 60, 71, 72, 85], 3 in Europe [50, 110, 112], 2 in South America [70, 108] and 1 in Australia [109]. Two US studies found an association between numeracy skills and higher adherence [72, 118]. Health literacy was also associated with better adherence in 2 US studies [59, 72] and 1 Japanese study [119], while a third US study did not find any association [60]. One Indian study found that better disease knowledge was associated with better adherence [62], though one Nigerian [115], as well as one US study [71] did not find any association between these two factors.

Caste and religion

One Indian study concluded that there was no association between caste and medication adherence [46] while another Indian study found a positive association between being religious and adherence [33]. Opposing these findings, another Indian study found that Hindu beliefs were associated with reduced adherence [46], but 3 African studies [37, 48, 81], as well as 2 Asian studies [32, 36] did not find any association between religion and adherence.

Family support (social)

Individuals who received social support by their families were more likely to be adherent, according to 1 Egyptian study [27], while another study conducted in Ghana [115] did not find any association.

Ethnical and geographical factors

All studies looking at ethnical and geographical factors are given in Table 2 where the studies are reported following the same criteria used for Table 1.

Ethnicity/race

A total of 19 studies looked at ethnical and racial differences in antidiabetic medication adherence [35,36,37, 39, 43, 51, 60, 71, 72, 83, 85, 86, 88,89,90, 99, 101, 104, 107, 111, 121,122,123,124,125,126,127,128, 131]. Fifteen studies on racial differences in medication adherence were conducted in the USA [51, 60, 72, 83, 86, 88,89,90, 104, 121, 123, 124, 127, 128, 131]. Two of these studies concluded that there were no racial differences in medication adherence [72, 123], while the remaining 13 studies found lower adherence for non-white ethnicities [51, 60, 83, 86, 88,89,90, 104, 121, 124, 127, 128, 131]. This association was found in black [51, 83, 86, 88,89,90, 128] and African-American [127], as well as in Latin-American and Hispanic subpopulations [88, 121, 131]. Similar results were found in New Zealand where 5 studies reported that non-European ethnicities resulted in lower medication adherence [35, 37, 122, 124, 126]. Other studies compared adherence differences between ethnic majorities and minorities in their countries (Table 3).

Country of birth and acculturation

Two studies conducted in the USA investigated the association between country of birth and medication adherence [71, 85], 1 study determined that individuals born in the USA were less likely to be adherent [71], while the other found no difference in adherence between foreign- and local-born individuals with T2DM [85]. One Australian study found a positive association between a high degree of acculturation and adherence, and an inverse relation between beliefs in traditional Chinese medicine and medication adherence [39].

Accessibility to health care, area of residence and regional differences

A British study found that having higher indices of multiple deprivation (IMD) was associated with an increase in adherence [125], and these findings are in line with 1 US study on neighbourhood deprivation [77] and 1 New Zealand study [37]. Opposing these findings, another study conducted in New Zealand did not find any association between socioeconomic living area and medication adherence [126]. Three studies found that urban area of residence is associated with a decrease in adherence [45, 58, 104]; opposing these findings, 3 studies found that a greater distance to a healthcare provider is associated with a decrease in adherence [31, 61, 101]. Six studies found no difference in adherence by area of residence [31, 80, 98, 100, 122, 130]. Two studies from the USA found differences in adherence depending on the region of their home state [95, 104], while a Spanish and a Lebanese study found no association between the different regions in the country and medication adherence [41, 110].

Discussion

Findings in context

Previous reviews have concluded that many individuals with T2DM show poor adherence to their medication regimen [15,16,17].

A systematic review conducted by Azharuddin et al. (2021) found non-adherence to be more likely in employed individuals [20]. It should be noted that the review did not include studies where no association was found. In the current systematic review, 2 studies were found showing an association between employed individuals and decreased adherence [52, 53]. The majority [18] did not find any association between employment and medication adherence [25, 32, 36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51]. Other studies looking at antidiabetic medication adherence in unemployed [54,55,56], retired individuals [57] or housewives [33] led to inconclusive results, as the direction of associations were contradictory. These findings are in line with a systematic review conducted by Wibowo et al. (2022) that found no conclusive association between employment and level of adherence [17].

Azharuddin et al. (2022) also found that lower income was associated with less adherence [20]. In the current systematic review, 9 studies found a positive association between high income and higher adherence [42, 52, 59,60,61,62,63,64,65]. Fifteen studies [25, 37, 41, 44, 46, 51, 54, 58, 66,67,68,69,70,71,72] found no association between different levels of income and only 1 study [73] found an inverse association. The association trend between non-adherence and lower income was also supported by 6 studies [74,75,76,77,78,79] that found reduced adherence for individuals reporting financial hardship, as well as 2 studies [67, 81] concluding that higher medication cost was associated with lower adherence. In line with these findings, 4 studies [26,27,28,29] found individuals with higher socioeconomic status more likely to be adherent. To be noted is that for socioeconomic status 8 studies [28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35] found no association in either direction. Low income is also associated with low education, and it could be speculated that this may lead to poor disease knowledge and management.

Azharuddin et al. (2021) and Wibowo et al. (2022) found a positive association between higher education and better medication adherence in their reviews [17, 20]. In the current review, 40 of the studies investigating the association between education and antidiabetic medication adherence found no difference between the varying levels of education [25, 28, 30, 31, 37, 43,44,45,46,47, 49,50,51,52, 54, 56, 59,60,61, 67, 70,71,72,73, 75, 81, 82, 85, 97, 98, 101, 106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114]. A total of 17 studies [24, 26, 27, 36, 38, 41, 42, 53, 55, 63, 64, 91, 100, 102, 115,116,117] found a positive association between higher education and level of adherence, while only 1 study [74] reported a negative association. These findings were supported by studies where a tendency towards non-adherence in illiterate individuals was observed [48, 62, 100], as well as studies that found people with higher adherence more likely to have higher numeracy skills [72, 118] and better disease knowledge [62]. Lower education may be related to lower knowledge on the impact and severity of T2DM and the importance of adherence to medication regimens, suggesting that patients’ education should be considered as a relevant factor when trying to improve patients’ medication use.

Peeters et al. (2011) found no association between ethnicity/race and adherence in their systematic review [18]. Comparing their conclusions to the results found in the current systematic review, lower adherence may be associated with non-white ethnicity in the USA, which 13 [51, 60, 83, 86, 88,89,90, 104, 121, 124, 127, 128, 131] out of 15 studies [51, 60, 72, 83, 86, 88,89,90, 104, 121, 123, 124, 127, 128, 131] concluded. A similar association was found in New Zealand where all 5 studies conducted resulted in lower adherence for non-European ethnicities [35, 37, 122, 124, 126]. Ethnicity and race as a whole may be associated with lower income, lower socioeconomic status and lower education as well [132], which all are associated with lower adherence themselves. These results highlight the relevance of ethnicity when assessing individuals’ adherence to medication or more generally, to physicians’ recommendations. Hence, one could speculate that ethnicity does not only influence the biological mechanisms behind medication efficacy but also the way individuals access the healthcare system and manage their health conditions.

The current review showed that insurance status appeared to be associated with medication adherence in individuals with T2DM. This was shown by 10 studies including individuals with no [45, 65, 67, 76, 87, 89] or governmentally provided insurance [77, 86,87,88] which found associations with lower adherence. Supporting this tendency, 5 studies [65, 92,93,94,95] concluded that individuals with higher co-payments tend to have lower adherence and 1 study found that capitated health plans [90] are associated with lower adherence. Furthermore, 3 studies have shown that individuals with commercial insurance are more likely to have higher medication adherence [42, 58, 91]. One study [51] also concluded that having health coverage is associated with higher adherence. These findings are in line with a systematic review conducted in Asia [17]. Intuitively, insurance status is strongly related to socioeconomic aspects including educational level and income, particularly in countries where the access to care is not equally guaranteed to everyone. One could speculate that in such contexts disadvantaged socioeconomic groups are more prone to problematic medication adherence.

Area of residence may be associated with adherence to some degree as well, as 2 studies [45, 58] found lower adherence to be more likely in individuals living in urban environments, and 1 study [104] showed an association between living in a rural environment and higher adherence. Nonetheless, 6 studies [31, 80, 98, 100, 122, 130] did not find any association between antidiabetic medication adherence and area of residence. Additionally, distance to healthcare providers was investigated in 3 studies [31, 61, 101], all of which concluded that greater distances are associated with lower adherence.

Results related to other factors including housing type, economic support, transportation availability, caste, living arrangement, religion, family support (social), country of birth, acculturation and regional differences led to vague conclusions.

The literature investigating antidiabetic medication adherence and socioeconomic factors associated with it is quite extensive. A large heterogeneity of methodologies, study populations and designs were observed. Additionally, the same factor may be of different relevance depending on the social context in which the factor is viewed and considered. Furthermore, for socioeconomic factors such as income, education, ethnicity/race, as well as insurance status, it is important to highlight that they are associated with each other, and may also interact, particularly when the research interest lies in investigating life course epidemiology rather than cross-sectional associations. For example, a study conducted in the USA found that both income and race are independently associated with lower insurance coverage. It was also found that the combination of having low income and being part of a minority resulted in an considerably lower probability for being insured [133]. This socioeconomic construct should be thought of as a whole when practitioners consider whether an individual with T2DM would benefit from supportive measures for adherence improvement. Finally, multiple different self-perceived reasons for non-adherence were identified in other studies, those mainly being lack of faith in the effectiveness of their treatment [134], low perception of the consequences of diabetes [134, 135], forgetfulness [136], fear of injections [136] and embarrassment of public injections [137] (140).

The World Health Organization stated in its 2003 report on medication adherence that increasing the effectiveness of adherence may result in far greater impact on the health of the population than any improvement in specific medical treatments [11]. Despite the widespread prevalence of medication, non-adherence and its impact on patients’ well-being and life conditions, this aspect, which is ultimately related to medication efficacy, is often under-detected and undertreated. To enhance health and avoid complications in individuals with T2DM, it is of major public health relevance to detect non-adherence and improve treatment management. Generating evidence on associations between specific socioeconomic factors and antidiabetic medication non-adherence can help practitioners to target and intervene on individuals’ non-adherent behaviours, aiming to improve patients’ education with respect to T2DM course and management.

Strengths

The large number of free-text search terms used for this systematic review increased inclusivity allowing to find a vast number of articles focusing on socioeconomic factors influencing antidiabetic medication adherence in individuals with T2DM. The thorough search enabled this systematic review to include the majority of articles on the topic in a global perspective. To the best of the authors knowledge, this is the first systematic review conducted under a global perspective on socioeconomic factors and antidiabetic medication adherence. Furthermore, a broader range of socioeconomic factors was investigated compared to other reviews, increasing knowledge on their associations with individuals’ adherence to antidiabetic medication.

Limitations

The comparability of the studies found was limited by the non-uniformity of the factors investigated. Additionally, antidiabetic medication adherence was measured in different ways. Most studies found used a cross-sectional study design in which most often subjective measures of adherence were applied. The cross-sectional study design frequently comes with other sources of error as well, including small sample sizes, recall bias, as well as survey bias. Many cross-sectional studies found did not utilize a validated method for their questionnaire or interview, which may increase the bias further. Moreover, objective measures such as pill count or medication possession rate have their flaws, as they do not guarantee that the patient has actually taken the medication.

In terms of limitations concerning the methodology of the current systematic review, the quality assessment tool is open to some degree of subjective interpretation. Although two researchers conducted the quality assessment independently and discussed to reach a common agreement, the NHLBI’s tool does not provide a stringent rule for rating the studies.

Conclusions and clinical implications

A range of socioeconomic factors associated with antidiabetic medication adherence was found. These factors may be taken into consideration when designing interventions to increase adherence. The studies included in this review vary greatly in terms of methodology, as well as quality. The factors such as insurance status and ethnicity/race consistently showed associations with antidiabetic medication adherence. Future research should aim to reduce the heterogeneity of the findings via a common validated methodology, allowing comparability between different studies.

Income, education, ethnicity/race and insurance are factors associated with adherence differences between patient groups, and these factors are also tightly intertwined with each other. When recommending treatments to patients, socioeconomic status should be considered, since increased awareness about differences and vulnerable groups may help to improve T2DM treatment management as a feasible short-term outcome, which in turn leads to enhancement of patients’ life quality in the long term.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

References

IDF Diabetes Atlas—10th Edition: International Diabetes Federation. Available from: https://diabetesatlas.org/.

Thibault V, Bélanger M, LeBlanc E, Babin L, Halpine S, Greene B, et al. Factors that could explain the increasing prevalence of type 2 diabetes among adults in a Canadian province: a critical review and analysis. Diabetol Metab Syndr. 2016;8(1):71.

Chatterjee S, Khunti K, Davies MJ. Type 2 diabetes. Lancet. 2017;389(10085):2239–51.

Mayyas FA, Ibrahim KS. Predictors of mortality among patients with type 2 diabetes in Jordan. BMC Endocr Disord. 2021;21(1):200.

Hirakawa Y, Tanaka T, Nangaku M. Mechanisms of metabolic memory and renal hypoxia as a therapeutic target in diabetic kidney disease. J Diabetes Investig. 2017;8(3):261–71.

NICE - Type 2 diabetes in adults management: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng28.

Davies MJ, D’ Alessio DA, Fradkin J, Kernan WN, Mathieu C, Mingrone G, et al. Management of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes, 2018. A consensus report by the American diabetes association (ADA) and the European association for the study of diabetes (EASD). Diabetes Care. 2018;41(12):2669–701.

Araki E, Goto A, Kondo T, Noda M, Noto H, Origasa H, et al. Japanese clinical practice guideline for diabetes 2019. Diabetol Int. 2020;11(3):165–223.

Hemoglobin A1c targets for glycemic control with pharmacologic therapy for nonpregnant adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a guidance statement update from the American college of physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2018;168(8):569–76.

Little RR, Sacks DB. HbA1c: How do we measure it and what does it mean? current opinion in endocrinology. Diabetes Obes. 2009. https://doi.org/10.1097/MED.0b013e328327728d.

Sabaté E. Adherence to long-term therapies: evidence for action. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2003. p. 19–21.

Cutler RL, Fernandez-Llimos F, Frommer M, Benrimoj C, Garcia-Cardenas V. Economic impact of medication non-adherence by disease groups: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2018;8(1): e016982.

Rand CS. Measuring adherence with therapy for chronic diseases: implications for the treatment of heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia. Am J Cardiol. 1993;72(10):68D-74D.

Vrijens B, De Geest S, Hughes DA, Przemyslaw K, Demonceau J, Ruppar T, et al. A new taxonomy for describing and defining adherence to medications. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2012;73(5):691–705.

Krass I, Schieback P, Dhippayom T. Adherence to diabetes medication: a systematic review. Diabet Med. 2015;32(6):725–37.

Cramer JA. A systematic review of adherence with medications for diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(5):1218–24.

Wibowo M, Yasin NM, Kristina SA, Prabandari YS. Exploring of determinants factors of anti-diabetic medication adherence in several regions of Asia-a systematic review. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2022;16:19.

Peeters B, Van Tongelen I, Boussery K, Mehuys E, Remon JP, Willems S. Factors associated with medication adherence to oral hypoglycaemic agents in different ethnic groups suffering from Type 2 diabetes: a systematic literature review and suggestions for further research. Diabet Med. 2011;28(3):262–75.

Al-Lela OQB, Abdulkareem RA, Al-Mufti L, Kamal N, Qasim S, Sagvan R, et al. Medication adherence among diabetic patients in developing countries: review of studies. Syst Rev Pharm. 2020;11(8):270–5.

Azharuddin M, Adil M, Sharma M, Gyawali B. A systematic review and meta-analysis of non-adherence to anti-diabetic medication: evidence from low- and middle-income countries. Int J Clin Pract. 2021;75(11):13.

Andrade SE, Kahler KH, Frech F, Chan KA. Methods for evaluation of medication adherence and persistence using automated databases. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2006;15(8):565–74.

Bissonnette JM. Adherence: a concept analysis. J Adv Nurs. 2008;63(6):634–43.

Study Quality Assessment Tools 2013: National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI). Available from: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools.

Acharya AS, Gupta E, Prakash A, Singhal N. Self-reported adherence to medication among patients with type ii diabetes mellitus attending a tertiary care hospital of Delhi. J Assoc Phys India. 2019;67(4):26–9.

Aravindakshan R, Abraham SB, Aiyappan R. Medication adherence to oral hypoglycemic drugs among individuals with Type 2 diabetes mellitus—a community study. Indian J Commun Med. 2021;46(3):503–7.

Yuksel M, Bektas H. Compliance with treatment and fear of hypoglycaemia in patients with type 2 diabetes. J Clin Nurs. 2021;30(11–12):1773–86.

Shams MEE, Barakat EAME. Measuring the rate of therapeutic adherence among outpatients with T2DM in Egypt. Saudi Pharm J. 2010;18(4):225–32.

Chandrika K, Das BN, Syed S, Challa S. Diabetes self-care activities: a community-based survey in an urban slum in Hyderabad, India. Indian J Commun Med. 2020;45(3):307–10.

Gopichandran V, Lyndon S, Angel MK, Manayalil BP, Blessy KR, Alex RG, et al. Diabetes self-care activities: a community-based survey in urban southern India. Natl Med J India. 2012;25(1):14–7.

Kowsalya P, Karthika, Krishna Kumar R, Joyce S, Thivya N. A study to assess the compliance to medication among type 2 diabetic patients at selected rural community in kanchipuram district, tamil nadu. Med Legal Update. 2020;20(2):128–31.

Olickal JJ, Chinnakali P, Suryanarayana BS, Saya GK, Ganapathy K, Subrahmanyam DKS. Medication adherence and glycemic control status among people with diabetes seeking care from a tertiary care teaching hospital, south India. Clin Epidemiol Glob Health. 2021;11:100742.

Pattnaik S, Ausvi SM, Salgar A, Sharma D. Treatment compliance among previously diagnosed type 2 diabetics in a rural area in Southern India. J Fam Med Prim Care. 2019;8(3):919–22.

Rao CR, Kamath VG, Shetty A, Kamath A. Treatment compliance among patients with hypertension and type 2 diabetes mellitus in a coastal population of southern India. Int J Prev Med. 2014;5(8):992–8.

Shams N, Amjad S, Kumar N, Ahmed W, Saleem F. Drug non-adherence in type 2 diabetes mellitus; predictors and associations. J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad JAMC. 2016;28(2):302–7.

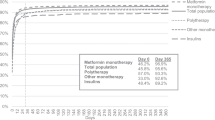

Horsburgh S, Barson D, Zeng J, Sharples K, Parkin L. Adherence to metformin monotherapy in people with type 2 diabetes mellitus in New Zealand. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2019;158:13.

Al-Haj Mohd MM, Phung H, Sun J, Morisky DE. The predictors to medication adherence among adults with diabetes in the United Arab Emirates. J Diabetes Metab Disord. 2015;15:30.

Bonger Z, Shiferaw S, Tariku EZ. Adherence to diabetic self-care practices and its associated factors among patients with type 2 diabetes in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2018;12:963–70.

Demoz GT, Wahdey S, Bahrey D, Kahsay H, Woldu G, Niriayo YL, et al. Predictors of poor adherence to antidiabetic therapy in patients with type 2 diabetes: a cross-sectional study insight from Ethiopia. Diabetol Metab Syndr. 2020;12(1):8.

Eh KX, McGill M, Wong J, Krass I. Cultural issues and other factors that affect self-management of Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2D) by Chinese immigrants in Australia. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2016;119:97–105.

Gomez-Peralta F, Perez JAF, Molinero A, Barrancos IMS, Martinez EA, Martinez-Perez P, et al. Adherence to antidiabetic treatment and impaired hypoglycemia awareness in type 2 diabetes mellitus assessed in Spanish community pharmacies: the ADHIFAC study. BMJ Open Diab Res Care. 2021;9(2):10.

Iqbal Q, Bashir S, Iqbal J, Iftikhar S, Godman B. Assessment of medication adherence among type 2 diabetic patients in Quetta city, Pakistan. Postgrad Med. 2017;129(6):637–43.

Koprulu F, Bader RJK, Hassan N, Abduelkarem AR, Mahmood DA. Evaluation of adherence to diabetic treatment in northern region of United Arab Emirates. Trop J Pharm Res. 2014;13(6):989–95.

Nasir NM, Ariffin F, Yasin SM. Physician-patient interaction satisfaction and its influence on medication adherence and type-2 diabetic control in a primary care setting. Med J Malaysia. 2018;73(3):163–9.

Pratama IPY, Andayani TM, Kristina SA. Knowledge, adherence and quality of life among type 2 diabetes mellitus patients. Int Res J Pharm. 2019;10(4):52–5.

Rezaie F, Laghousi D, Alizadeh M. Medication adherence and associated factors among type II diabetic patients in East Azerbaijan, Iran. Turk J Endocrinol Metab. 2019;23(3):158–67.

Roy S, Reang T. Adherence to treatment among type 2 diabetes patients attending tertiary care hospital in Agartala city—a cross-sectional study. J Evol Med Dent Sci-JEMDS. 2018;7(10):1223–7.

Sajith M, Pankaj M, Pawar A, Modi A, Sumariya R. Medication adherence to antidiabetic therapy in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2014;6(SUPPL. 2):564–70.

Sefah IA, Okotah A, Afriyie DK, Amponsah SK. Adherence to oral hypoglycemic drugs among type 2 diabetic patients in a resource-poor setting. Int J Appl Basic Med Res. 2020;10(2):102–9.

Zairina E, Nugraheni G, Sulistyarini A, Mufarrihah, Setiawan CD, Kripalani S, et al. Factors related to barriers and medication adherence in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a cross-sectional study. J Diabetes Metab Disord. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40200-021-00961-6.

Horvat O, Poprzen J, Tomas A, Kusturica MP, Tomic Z, Sabo A. Factors associated with non-adherence among type 2 diabetic patients in primary care setting in eastern Bosnia and Herzegovina. Prim Care Diabetes. 2018;12(2):147–54.

Trief PM, Kalichman SC, Wang D, Drews KL, Anderson BJ, Bulger JD, et al. Medication adherence in young adults with youth-onset type 2 diabetes: iCount, an observational study. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2022;184: 109216.

Suzuki R, Saita S, Nishigaki N, Kisanuki K, Shimasaki Y, Mineyama T, et al. Factors associated with treatment adherence and satisfaction in type 2 diabetes management in Japan: results from a web-based questionnaire survey. Diabetes Ther. 2021;12(9):2343–58.

Raum E, Krämer HU, Rüter G, Rothenbacher D, Rosemann T, Szecsenyi J, et al. Medication non-adherence and poor glycaemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2012;97(3):377–84.

Ashur ST, Shah SA, Bosseri S, Morisky DE, Shamsuddin K. Illness perceptions of Libyans with T2DM and their influence on medication adherence: a study in a diabetes center in Tripoli. Libyan J Med. 2015. https://doi.org/10.3402/ljm.v10.29797.

Bruce SP, Acheampong F, Kretchy I. Adherence to oral anti-diabetic drugs among patients attending a Ghanaian teaching hospital. Pharm Pract. 2015. https://doi.org/10.18549/pharmpract.2015.01.533.

Adisa R, Alutundu MB, Fakeye TO. Factors contributing to nonadherence to oral hypoglycemic medications among ambulatory type 2 diabetes patients in Southwestern Nigeria. Pharm Pract (Granada). 2009;7(3):163–9.

Maruan K, Isa KAM, Sulaiman N, Karuppannan M. Adherence of patients with type 2 diabetes to refills and medications: a comparison between “telephone and collect” and conventional counter services in a health clinic. Drugs Ther Perspect. 2020;36(12):590–7.

Gibson TB, Song X, Alemayehu B, Wang SS, Waddell JL, Bouchard JR, et al. Cost sharing, adherence, and health outcomes in patients with diabetes. Am J Manag Care. 2010;16(8):589–600.

Fan JH, Lyons SA, Goodman MS, Blanchard MS, Kaphingst KA. Relationship between health literacy and unintentional and intentional medication nonadherence in medically underserved patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Educ. 2016;42(2):199–208.

Huang YM, Shiyanbola OO, Smith PD. Association of health literacy and medication self-efficacy with medication adherence and diabetes control. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2018;12:793–802.

Mannan A, Hasan MM, Akter F, Rana MM, Chowdhury NA, Rawal LB, et al. Factors associated with low adherence to medication among patients with type 2 diabetes at different healthcare facilities in southern Bangladesh. Glob Health Action. 2021;14(1):7.

Mukherjee S, Sarkar BS, Das KK, Bhattacharyya A, Deb A. Original articlecompliance to anti-diabetic drugs: observations from the diabetic clinic of a medical college in Kolkata, India. J Clin Diagn Res. 2013;7(4):661–5.

Al-Majed HT, Ismael AE, Al-Khatlan HM, El-Shazly MK. Adherence of type-2 diabetic patients to treatment. Kuwait Med J. 2014;46(3):225–32.

Kirkman MS, Rowan-Martin MT, Levin R, Fonseca VA, Schmittdiel JA, Herman WH, et al. Determinants of adherence to diabetes medications: findings from a large pharmacy claims database. Diabetes Care. 2015;38(4):604–9.

Ngo-Metzger Q, Sorkin DH, Billimek J, Greenfield S, Kaplan SH. The effects of financial pressures on adherence and glucose control among racial/ethnically diverse patients with diabetes. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(4):432–7.

Afaya RA, Bam V, Azongo TB, Afaya A, Kusi-Amponsah A, Ajusiyine JM, et al. Medication adherence and self-care behaviours among patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus in Ghana. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(8):14.

Ajibola SS, Timothy FO. The influence of national health insurance on medication adherence among outpatient type 2 diabetics in Southwest Nigeria. J Patient Exp. 2018;5(2):114–9.

Irani M, Yazdi MS, Irani M, Sistani SN, Ghareh S. Evaluation of adherence to oral hypoglycemic agent prescription in patients with type 2 diabetes. Rev Diabetic Stud RDS. 2020;16:41–5.

Kurlander JE, Kerr EA, Krein S, Heisler M, Piette JD. Cost-related nonadherence to medications among patients with diabetes and chronic pain: factors beyond finances. Diabetes Care. 2009;32(12):2143–8.

Saraiva EMS, Coelho JLG, dos Santos Figueiredo FW, de Souto RP. Medication non-adherence in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus with full access to medicines. J Diabetes Metab Disord. 2020;19(2):1105–13.

Garcia ML, Castaneda SF, Allison MA, Elder JP, Talavera GA. Correlates of low-adherence to oral hypoglycemic medications among Hispanic/Latinos of Mexican heritage with type 2 diabetes in the United States. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2019;155:10.

Nandyala AS, Nelson LA, Lagotte AE, Osborn CY. An analysis of whether health literacy and numeracy are associated with diabetes medication adherence. Health Lit Res practice. 2018;2(1):e15–20.

Chew BH, Hassan NH, Sherina MS. Determinants of medication adherence among adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus in three Malaysian public health clinics: a cross-sectional study. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2015;9:639–48.

Aminde LN, Tindong M, Ngwasiri CA, Aminde JA, Njim T, Fondong AA, et al. Adherence to antidiabetic medication and factors associated with non-adherence among patients with type-2 diabetes mellitus in two regional hospitals in Cameroon. BMC Endocr Disord. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12902-019-0360-9.

Arifulla M, John LJ, Sreedharan J, Muttappallymyalil J, Basha SA. Patients’ adherence to anti-diabetic medications in a Hospital at Ajman, UAE Malaysian. J Med Sci. 2014;21(1):44–9.

Bermeo-Cabrera J, Almeda-Valdes P, Riofrios-Palacios J, Aguilar-Salinas CA, Mehta R. Insulin adherence in type 2 diabetes in Mexico: behaviors and barriers. J Diabetes Res. 2018;2018:7.

Billimek J, August KJ. Costs and beliefs: understanding individual- and neighborhood-level correlates of medication nonadherence among Mexican Americans with type 2 diabetes. Health Psychol. 2014;33(12):1602–5.

Wabe NT, Angamo MT, Hussein S. Medication adherence in diabetes mellitus and self management practices among type-2 diabetics in Ethiopia. N Am J Med Sci. 2011;3(9):418–23.

Yusuff KB, Obe O, Joseph BY. Adherence to anti-diabetic drug therapy and self management practices among type-2 diabetics in Nigeria. Pharm World Sci. 2008;30(6):876–83.

Pihau-Tulo ST, Parsons RW, Hughes JD. An evaluation of patients’ adherence with hypoglycemic medications among Papua New Guineans with type 2 diabetes: influencing factors. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2014;8:1229–37.

Rwegerera GM. Adherence to anti-diabetic drugs among patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus at Muhimbili National Hospital, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania-a cross-sectional study. Pan Afr Med J. 2014;17:252.

Badi S, Abdalla A, Altayeb L, Noma M, Ahmed MH. Adherence to antidiabetic medications among Sudanese individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a cross-sectional survey. J Patient Exp. 2020;7(2):163–8.

Kreyenbuhl J, Dixon LB, McCarthy JF, Soliman S, Ignacio RV, Valenstein M. Does adherence to medications for type 2 diabetes differ between individuals with VS without schizophrenia? Schizophr Bull. 2010;36(2):428–35.

Zairina E, Nugraheni G, Sulistyarini A, Mufarrihah, Setiawan CD, Kripalani S, et al. Factors related to barriers and medication adherence in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a cross-sectional study. J Diabetes Metab Disord.10.

Parada H, Horton LA, Cherrington A, Ibarra L, Ayala GX. Correlates of medication nonadherence among Latinos with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Educ. 2012;38(4):552–61.

Beltran S, Arenas DJ, Lopez-Hinojosa IJ, Tung EL, Cronholm PF. Associations of race, insurance, and zip code-level income with nonadherence diagnoses in primary and specialty diabetes care. J Am Board Fam Med. 2021;34(5):891–7.

Wei W, Jiang J, Lou Y, Ganguli S, Matusik MS. Benchmarking insulin treatment persistence among patients with type 2 diabetes across different U.S. payer segments. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2017;23(3):278–90.

Beltrán S, Elle L, Cronholm PF. Nonadherence labeling in primary care: bias by race and insurance type for adults with type 2 diabetes. Am J Prev Med. 2019;57(5):652–8.

Trief PM, Izquierdo R, Eimicke JP, Teresi JA, Goland R, Palmas W, et al. Adherence to diabetes self care for white, African-American and Hispanic American telemedicine participants: 5 year results from the IDEATel project. Ethn Health. 2013;18(1):83–96.

Pawaskar M, Burch S, Seiber E, Nahata M, Iaconi A, Balkrishnan R. Medicaid payment mechanisms: impact on medication adherence and health care service utilization in type 2 diabetes enrollees. Popul Health Manag. 2010;13(4):209–18.

Simon-Tuval T, Shmueli A, Harman-Boehm I. Adherence of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus to medications: the role of risk preferences. Curr Med Res Opin. 2018;34(2):345–51.

Barron J, Wahl P, Fisher M, Plauschinat C. Effect of prescription copayments on adherence and treatment failure with oral antidiabetic medications. Pharm Ther. 2008;33(9):532–40+53.

Colombi AM, Yu-Isenberg K, Priest J. The effects of health plan copayments on adherence to oral diabetes medication and health resource utilization. J Occup Environ Med. 2008;50(5):535–41.

Henk HJ, Lopez JMS, Bookhart BK. Novel type 2 diabetes medication access and effect of patient cost sharing. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2018;24(9):847–55.

Malmenäs M, Bouchard JR, Langer J. Retrospective real-world adherence in patients with type 2 diabetes initiating once-daily liraglutide 1.8 mg or twice-daily exenatide 10 μg. Clin Ther. 2013;35(6):795–807.

Asalde CAB, De Bonilla ORL, Lozada ICR, Carrasco VB, Pizarro DNB, Huamani LC, et al. Barriers to accessing quality health coverage and their association with medication adherence in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus at a hospital in Peru. Pak J Med Health Sci. 2020;14(2):853–9.

Berhe KK, Demissie A, Kahsay AB, Gebru HB. Diabetes self care practices and associated factors among type 2 diabetic patients in Tikur Anbessa specialized hospital, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia-a cross sectional study. Int J Pharm Sci Res. 2012;3(11):4219–29.

Halepian L, Saleh MB, Hallit S, Khabbaz LR. Adherence to insulin, emotional distress, and trust in physician among patients with diabetes: a cross-sectional study. Diabetes Ther. 2018;9(2):713–26.

Lee CS, Tan JHM, Sankari U, Koh YLE, Tan NC. Assessing oral medication adherence among patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus treated with polytherapy in a developed Asian community: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2017;7(9):7.

Mirahmadizadeh A, Delam H, Seif M, Banihashemi SA, Tabatabaee H. Factors affecting insulin compliance in patients with type 2 diabetes in South Iran, 2017: we are faced with insulin phobia. Iran J Med Sci. 2019;44(3):204–13.

Abdul Salam M, Farheen SA. Socio-demographic determinants of compliance among type 2 diabetic patients in Abha, Saudi Arabia. J Clin Diagn Res. 2013;7(12):2810–3.

Prathap RF, Suresh M, Rajeev MM, Saji JC, Bharanidharan SE, Vellaichamy G. A descriptive cross-sectional study on medication adherence of oral antidiabetic agents in diabetes mellitus patients and an overview on clinical pharmacist’s role in medication adherence in government headquarters hospital Tiruppur. J Diabetol. 2021;12(2):164–71.

Mirahmadizadeh A, Khorshidsavar H, Seif M, Sharifi MH. Adherence to medication, diet and physical activity and the associated factors amongst patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Ther. 2020;11(2):479–94.

Egede LE, Gebregziabher M, Hunt KJ, Axon RN, Echols C, Gilbert GE, et al. Regional, geographic, and ethnic differences in medication adherence among adults with type 2 diabetes. Ann Pharmacother. 2011;45(2):169–78.

Jackson IL, Adibe MO, Okonta MJ, Ukwe CV. Medication adherence in type 2 diabetes patients in Nigeria. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2015;17(6):398–404.

Xie Z, Liu K, Or C, Chen J, Yan M, Wang H. An examination of the socio-demographic correlates of patient adherence to self-management behaviors and the mediating roles of health attitudes and self-efficacy among patients with coexisting type 2 diabetes and hypertension. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):1227.

Ahmad NS, Ramli A, Islahudin F, Paraidathathu T. Medication adherence in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus treated at primary health clinics in Malaysia. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2013;7:525–30.

Arrelias CCA, Faria HTG, Teixeira CRD, dos Santos MA, Zanetti ML. Adherence to diabetes mellitus treatment and sociodemographic, clinical and metabolic control variables. Acta Paul Enferm. 2015;28(4):315–22.

Gomez-Peralta F, Fornos Pérez JA, Molinero A, Sánchez Barrancos IM, Arranz Martínez E, Martínez-Pérez P, et al. Adherence to antidiabetic treatment and impaired hypoglycemia awareness in type 2 diabetes mellitus assessed in Spanish community pharmacies: the ADHIFAC study. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjdrc-2021-002148.

Jannoo Z, Khan NM. Medication adherence and diabetes self-care activities among patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Value Health Reg Iss. 2019;18:30–5.

Pinto DM, Santiago LM, Mauricio K, Silva IR. Health profile and medication adherence of diabetic patients in the Portuguese population. Prim Care Diabetes. 2019;13(5):446–51.

Shlash RA, Rabeea IS. Evaluation of diabetic-medications adherence among diabetic type 2 patients. Indian J Forensic Med Toxicol. 2021;15(2):1920–7.

Farsaei S, Sabzghabaee AM, Zargarzadeh AH, Amini M. Adherence to glyburide and metformin and associated factors in type 2 diabetes in Isfahan, Iran. Iran J Pharm Res. 2011;10(4):933–9.

Huang YM, Shiyanbola OO, Chan HY. A path model linking health literacy, medication self-efficacy, medication adherence, and glycemic control. Patient Educ Couns. 2018;101(11):1906–13.

Afaya RA, Bam V, Azongo TB, Afaya A, Kusi-Amponsah A, Ajusiyine JM, et al. Medication adherence and self-care behaviours among patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus in Ghana. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(8): e0237710.

Benrazavy L, Ali K. Medication adherence and its predictors in type 2 diabetic patients referring to urban primary health care centers in kerman city, southeastern iran. Shiraz E Med J. 2019;20(7).

Hosseini-Marznaki Z, Tabari-Khomeiran R, Taheri-Ezbarami Z, Kazemnejad E. Adherence to treatment and its predictive factors among adults with type 2 diabetes in northern Iran. Mediterr J Nutr Metab. 2019;12(1):45–59.

Ueno H, Ishikawa H, Suzuki R, Izumida Y, Ohashi Y, Yamauchi T, et al. The association between health literacy levels and patient-reported outcomes in Japanese type 2 diabetic patients. SAGE Open Med. 2019;7:2050312119865647.

Lopez JM, Bailey RA, Rupnow MF, Annunziata K. Characterization of type 2 diabetes mellitus burden by age and ethnic groups based on a nationwide survey. Clin Ther. 2014;36(4):494–506.

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372: n71.

Nelson LA, Ackerman MT, Greevy RA, Wallston KA, Mayberry LS. Beyond race disparities: accounting for socioeconomic status in diabetes self-care. Am J Prev Med. 2019;57(1):111–6.

McGovern A, Hinton W, Calderara S, Munro N, Whyte M, de Lusignan S. A class comparison of medication persistence in people with type 2 diabetes: a retrospective observational study. Diabetes Ther. 2018;9(1):229–42.

Juarez DT, Tan C, Davis JW, Mau MM. Using quantile regression to assess disparities in medication adherence. Am J Health Behav. 2014;38(1):53–62.

Shenolikar RA, Balkrishnan R, Camacho FT, Whitmire JT, Anderson RT. Race and medication adherence in Medicaid enrollees with type-2 diabetes. J Natl Med Assoc. 2006;98(7):1071–7.

Horsburgh S, Sharples K, Barson D, Zeng J, Parkin L. Patterns of metformin monotherapy discontinuation and reinitiation in people with type 2 diabetes mellitus in New Zealand. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(4): e0250289.

Kharjul MD, Cameron C, Braund R. Using the pharmaceutical collection database to identify patient adherence to oral hypoglycaemic medicines. J Prim Health Care. 2019;11(3):265–74.

Gebregziabher M, Lynch CP, Mueller M, Gilbert GE, Echols C, Zhao Y, et al. Using quantile regression to investigate racial disparities in medication non-adherence. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2011;11:88.

Fernandez A, Quan J, Moffet H, Parker MM, Schillinger D, Karter AJ. Adherence to newly prescribed diabetes medications among insured Latino and White patients with diabetes. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(3):371–9.

Reeves R, Rodrigues E, Kneebone E. Five evils: multidimensional poverty and race in America. Washington D.C.: Brookings Institution; 2016.

Fernández A, Quan J, Moffet H, Parker MM, Schillinger D, Karter AJ. Adherence to newly prescribed diabetes medications among insured Latino and White patients with diabetes. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(3):371–9.

Chepulis L, Mayo C, Morison B, Keenan R, Lao C, Paul R, et al. Metformin adherence in patients with type 2 diabetes and its association with glycated haemoglobin levels. J Prim Health Care. 2020;12(4):318–26.

Lee D-C, Liang H, Shi L. The convergence of racial and income disparities in health insurance coverage in the United States. Int J Equity Health. 2021;20(1):96.

Onwuchuluba EE, Oyetunde OO, Soremekun RO. Medication adherence in type 2 diabetes mellitus: a qualitative exploration of barriers and facilitators from socioecological perspectives. J Patient Exp. 2021;8:23743735211034336.

Broadbent E, Donkin L, Stroh JC. Illness and treatment perceptions are associated with adherence to medications, diet, and exercise in diabetic patients. Diabetes Care. 2011;34(2):338–40.

Nelson LA, Wallston KA, Kripalani S, LeStourgeon LM, Williamson SE, Mayberry LS. Assessing barriers to diabetes medication adherence using the information-motivation-behavioral skills model. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2018;142:374–84.

Peyrot M, Barnett AH, Meneghini LF, Schumm-Draeger PM. Insulin adherence behaviours and barriers in the multinational global attitudes of patients and physicians in insulin therapy study. Diabetes Med A J Br Diabet Assoc. 2012;29(5):682–9.

Davies MJ, Gagliardino JJ, Gray LJ, Khunti K, Mohan V, Hughes R. Real-world factors affecting adherence to insulin therapy in patients with type 1 or type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review. Diabet Med. 2013;30(5):512–24.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Karolinska Institute. This work and LP were supported by FORTE, Swedish Research Council for Health, Working Life and Welfare with a Junior Research Grant (project no. 2021–01080) to LP.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The author CMS conducted the primary screening (titles and abstracts) of the literature retrieving the articles which are included in this work. The secondary full-text screening of the articles was conducted by CMS and LP independently, and when agreement could not be reached, ML provided external input. CMS and LP drafted the manuscript, and ML critically revised and added contributions to the drafted manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

ML reports participation in research projects funded by pharmaceutical companies, all regulator-mandated phase IV studies, all with funds paid to the institution where she was employed (no personal fees) and with no relation to the work reported in this paper. The other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Appendix 1.

Exact searches of individual databases conducted on the 15.03.2022.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Studer, C.M., Linder, M. & Pazzagli, L. A global systematic overview of socioeconomic factors associated with antidiabetic medication adherence in individuals with type 2 diabetes. J Health Popul Nutr 42, 122 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41043-023-00459-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41043-023-00459-2