Abstract

Background

High blood pressure or hypertension has become one of the main health problems, worldwide. A number of studies have proven that an increased intake of salt was related to an increased prevalence of cardiovascular diseases. Of late, its relationship with high salt intake has received a lot of attention. Studies in Malaysia have shown both rising hypertension over time as well as high salt consumption. Actions to reduce salt intake are essential to reduce hypertension and its disease burden. As such, we carried out a study to determine associations between knowledge, attitude and behaviour towards salt intake and hypertension among the Malaysian population.

Methods

Data obtained from the Malaysian Community Salt Survey (MyCoSS) was used partially for this study. The survey used a cross-sectional two-stage sampling design to select a nationally representative sample of Malaysian adults aged 18 years and above living in non-institutional living quarters (LQ). Face-to-face interviews were done by trained research assistants (RA) to obtain information on sociodemography, medical report, as well as knowledge, attitude and behaviour of the respondents towards salt intake and blood pressure.

Results

Majority of the respondents have been diagnosed with hypertension (61.4%) as well as knowledge of the effects of high salt intake on blood pressure (58.8%). More than half of the respondents (53.3%) said they controlled their salt intake on a regular basis. Those who knew that a high salt diet could contribute to a serious health problem (OR=0.23) as well as those who controlled their salt intake (OR=0.44) were significantly less likely to have hypertension.

Conclusion

Awareness of the effects of sodium on human health, as well as the behaviour of controlling salt intake, is essential towards lowering the prevalence of hypertension among Malaysians.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Hypertension is a common condition, which if not detected and treated early, can lead to myocardial infarction, stroke, renal failure, and premature death [1]. With over 9.4 million deaths worldwide, it has been predicted that there will be up to 75% increment of global cardiovascular disease burden by the year 2020 [2,3,4]. The relationship between cardiovascular diseases and elevation in blood pressure in relation to salt is currently a major focus of scientific research [5]. According to Parmar et al. [6], the most important factor causing elevation of human blood pressure is salt intake. Consuming excessive dietary salt contributes to high blood pressure [7, 8]. Zhang et al. [9] suggest that the best way to control hypertension is by increasing awareness of this disease and promoting healthy salt intake behaviour.

In Malaysia, a few studies have reported that the average salt intake exceeds that recommended for health by the World Health Organization (WHO) [10, 11]. It is recommended to take not more than 5 g of salt every day in order to reduce the number of deaths related to hypertension, cardiovascular diseases as well as stroke [12]. In view of efforts to reduce salt consumption, it is imperative to find out the level of awareness among Malaysians on this issue. More importantly, we also need to investigate if awareness has any association with diagnosis of hypertension. Thus, the objective of this study was to determine knowledge, attitude, and behaviour related to salt intake, and their associations with hypertension in the Malaysian population. This information is important as a baseline for monitoring purposes and also for developing new strategies and promotional activities on salt reduction in the country.

Methods

The data for this study was drawn from the Malaysian Community Salt Survey (MyCoSS), a nationwide cross-sectional study, conducted among Malaysian adults aged 18 years and above living in non-institutional living quarters (LQ). The sample size was calculated by assessing population prevalence based on the most recent salt study in Malaysia [13]. It was ensured to cover both urban and rural areas as well as proportionate to the size of the population according to states in Malaysia (Fig. 1). The estimated sample size was 1440 participants. Exclusion criteria of this study were those who were pregnant, recently began diuretic therapy (<4 weeks), having menses and diagnosed with kidney disease, heart failure disease or liver disease. Diagnosis of hypertension was based on medical report questions in Module C of the questionnaire (Fig. 2).

Knowledge, attitude and behaviour

The knowledge, attitude and behaviour on salt intake questionnaire which was translated into Malay language and back-translated to English to ensure the quality of the translation, was adapted from the World Health Organization/Pan American Health Organization protocol for population-level sodium determination [14]. The flow chart in Fig. 2 shows the respondent feedback on the knowledge, attitude and behaviour towards dietary sodium intake. The data collection was carried out by trained interviewers via face-to-face interview. All interviewers were trained at the central level.

Sociodemographic information

Interviewer-administered questionnaires were used to collect information on sociodemography and medical report of the respondents. Variables such as gender, age, occupation, ethnicity, as well as individual income were selected for use in this study.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was carried out using STATA Ver 15.0. The complex sample design of the study and weights were taken into account by using the svy suite for all analysis. Variance estimation was carried out using the Taylor series linearization method, and bivariate analysis was carried out using the Rao-Scott F test. Subpopulation analysis was carried out on the groups with diagnosed hypertension. Design-adjusted Wald test was used to evaluate the significance of each variable in the logistic regression model. All analysis was described using 95% confidence intervals and statistical significance at p-value of less than 0.05.

Results

The total number of respondents in MyCoSS was 1440. After excluding based on the exclusion criteria, the total number was reduced to 1047 (72.7%). Table 1 shows the age, ethnic background, marital status, education and income level of the respondents. Most of the respondents were female (59.1%), aged between 55 to 64 years old (23.3%), Malay (63.2%) and married (72.7%). The majority had at least attained secondary education (48.0%), and 21.8% had higher education. Most of the respondents were housewives (28.5%), and most reported a household income of less than RM 1000/month (31.0%), and the number of respondents with diagnosed hypertension was 339 (34.1%).

Table 2 shows associations between selected sociodemographic characteristics and diagnosed hypertension status among respondents. Compared to those who claimed to have no knowledge, a significantly higher proportion (83.0%, 95% CI 64.19, 92.99) of respondents who said yes to having knowledge that a high salt diet can cause health problems have diagnosed hypertension (p = 0.012). Among those who said they do not take regular measures to control their salt intake, 70.1% have had a hypertension diagnosis compared to 53.3% among those who say they do regularly control their salt intake (p = 0.025).

Table 3 shows the odds ratio between sociodemographic characteristics and diagnosed hypertension among respondents. A lower likelihood of having diagnosed hypertension was found for respondents with knowledge of high salt diet causing a serious health problem (OR= 0.23, 95% CI 0.06, 0.85), those who practise controlling salt intake (OR= 0.44, 95% CI 0.21, 0.91) and those with household income of RM 2000 to RM 2999 (OR= 0.28, 95% CI 0.13, 0.62).

Discussion

Hypertension is a common and serious worldwide public health problem that can lead to high mortality and morbidity rates. It has been identified as one major risk factor for cardiovascular diseases and chronic kidney disease. This study revealed that the prevalence of hypertension was about 34.1%. The prevalence obtained in this study seems to be similar closer to 32.7% as cited by NHMS 2011 but lower than the WHO 2008 estimate (34.0%) in the South-East Asia region [15]. The difference in the WHO 2008 estimate may be due to the wider scope and population covered in the WHO study.

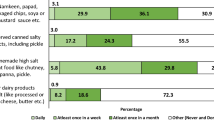

From several previous studies, it is known that knowledge, attitude and behaviour toward hypertension and salt intake play a significant role in controlling blood pressure and as a preventive measure for hypertension [16, 17]. In this study, majority of the respondents (83.0%) had good knowledge of salt intake as they agreed that a high salt diet could contribute to serious health problems. On the other hand, the findings also indicated that some respondents did not have basic exposure to information on hypertension and salt intake. This finding of widespread awareness coincides with several other studies which found a good level of exposure and knowledge about hypertension and salt intake in their study populations [18,19,20,21]. However, despite knowing the facts, 60.9% of respondents perceived lowering their salt intake as not at all important. This is indicative of a poor attitude. Furthermore, almost 30.0% of respondents (total from n=993) did not take any regular measures to control salt or sodium intake. Even more disappointing, a majority of those who did not control their salt intake have had hypertension diagnosed. Three studies in Nigeria and Bangladesh showed comparable results to ours whereby a majority of their respondents had good knowledge but poor practice related to hypertension and salt intake [22,23,24]. It is possible that the poor attitude in our study population on the importance of lowering salt or sodium intake may be due to lack of awareness. The MySalt 2015 study in Malaysia showed a contrasting result, as the respondents involved were health staff, that there were good knowledge and attitude towards salt intake as well as moderate to good practise on salt control or sodium intake [13].

For risk assessment, our study identified respondents’ household income and knowledge of salt intake as the lifestyle risk factor associated with hypertension. Compared to other studies that showed age as an important non-modifiable risk factor for hypertension [25,26,27], our study showed a contrasting result, where the age of respondents was not a significant predictor for hypertension. From the data analysis, we found that respondents with a monthly household income of RM 2000 to RM 2999 had lower odds of getting hypertension compared to respondents with a household income of less than RM 1000. Based on NHMS 2011 findings, the lower (< RM 400) and higher (RM 3000 to RM 3999) household income levels had higher odds of getting hypertension [28]. Previous studies revealed that the association between respondents’ economic status, whether in terms of wealth index or household asset, and the prevalence of hypertension was controversial [29]. This may be due to differences in study population or other confounding factors such as cultural and sociobehavioural factors.

Low awareness towards salt intake is considered as a risk factor for hypertension [21]. The knowledge that high salt consumption could cause a serious health problem is related to diagnosed hypertension. A study conducted in Nigeria demonstrated that inadequate hypertension-related knowledge was an independent risk factor for hypertension [17]. Pandit et al. [30] revealed that educational status and level of knowledge about hypertension were important to help in controlling blood pressure levels especially among patients with diagnosed hypertension. Hence, knowledge of hypertension and salt intake is very important for the general population so that they could be aware as well as evaluate their general health status [31].

Moreover, practising healthier dietary behaviour requires one to possess both knowledge and skill since the sodium intake is not fully determined by knowledge, attitude and behaviour of consumer but other roles such as cultures. Delivering education to population should not be limited to information on health and sodium but also provide both practical and culturally appropriate to improve their diet [32]. People should be made aware of hidden sodium and other sources of sodium in their diet. Furthermore, campaigns on using low sodium condiments or alternative forms of flavouring should be introduced and recommended [11].

The barriers of poor awareness, attitude and behaviours should be a concern and be given attention in hypertension preventive efforts. Educational and awareness programmes should be developed based on the demands of the society in order to improve the knowledge, change the attitude and enhance the behaviour within the general population towards hypertension and salt intake. Besides, gaps between knowledge, attitudes and behaviours should be identified as it is crucial to formulate and implement clear strategies by which the knowledge and positive attitudes can be converted into beneficial behaviours [6].

Limitations

Knowledge, attitudes and behaviour questionnaire is based on limited questions and self-reported data. Therefore, the questions may have been misunderstood by the respondent. The tendency of having social desirability bias is also high. Moreover, question with choices lack of flexibility due to fixed choices given. This study was based on MyCoSS which was the first study in Malaysia related to salt intake, hence, not enough data to compare with.

This study is a cross-sectional study. Hence, we cannot determine the relationship between respondents’ knowledge of the amount of salt in the diet and diagnosed hypertension as a causal relationship. This study was based on MyCoSS which was the first study in Malaysia related to salt intake, hence, not enough data to compare with.

Conclusions

In conclusion, having the knowledge of the amount of salt in the diet and the effect of salt towards human health, as well as the behaviour of regulating the intake of salt, is related to hypertension among the Malaysian population. This important information could be the baseline information towards future studies as well as in enabling steps to be taken towards reducing salt consumption among Malaysians.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable requests.

Abbreviations

- MyCoSS:

-

Malaysian Community Salt Survey

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

References

James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, Cushman WC, Dennison-Himmelfarb C, Handler J, et al. 2014 evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: report from the panel members appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8). Jama. 2014;311(5):507–20.

Dhemla S, Varma K. Worldwide consumption of sodium and its impact on human health. Int J Recent Innov Trends Comput Commun. 2017;5(6):62–7.

Lim SS, Vos T, Flaxman AD, Danaei G, Shibuya K, Adair-Rohani H, et al. A comparative risk assessment of burden of disease and injury attributable to 67 risk factors and risk factor clusters in 21 regions, 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380(9859):2224–60.

Gupta R. Trends in hypertension epidemiology in India. J Hum Hypertens. 2004;18(2):73.

Ha SK. Dietary salt intake and hypertension. Electrolytes Blood Pressure. 2014;12(1):7–18.

Parmar P, Rathod GB, Rathod S, Goyal R, Aggarwal S, Parikh A. Study of knowledge, attitude and practice of general population of Gandhinagar towards hypertension. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. Appl. Sci. 2014;3(8):680–5.

Mente A, O’Donnell M, Rangarajan S, Dagenais G, Lear S, McQueen M, et al. Associations of urinary sodium excretion with cardiovascular events in individuals with and without hypertension: a pooled analysis of data from four studies. Lancet. 2016;388(10043):465–75.

Graudal N, Jürgens G, Baslund B, Alderman MH. Compared with usual sodium intake, low-and excessive-sodium diets are associated with increased mortality: a meta-analysis. Am J Hypertens. 2014;27(9):1129–37.

Zhang Y, Moran AE. Trends in the prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension among young adults in the United States, 1999 to 2014. Hypertension. 2017;70(4):736–42.

Mahat D, Isa ZM, Tamil AM, Mahmood MI, Othman F, Ambak R. The association of knowledge, attitude and practice with 24 hours urinary sodium excretion among Malay healthcare staff in Malaysia. Int J Public Health Res. 2017;7(2):860–70.

Amarra MS, Khor GL. Sodium consumption in Southeast Asia: an updated review of intake levels and dietary sources in six countries. In: Preventive Nutrition. Cham: Springer; 2015. p. 765–92.

World Health Organization. Reducing salt intake in populations: report of a WHO forum and technical meeting. Paris, France; 2007. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/43653/9789241595377_eng.pdf.

Institute for Public Health (IPH). Determination of dietary sodium intake among the Ministry of Health staff 2015 (MySalt 2015). Kuala Lumpur: Ministry of Health; 2016.

World Health Organization. WHO/PAHO Regional Expert Group for Cardiovascular Disease Prevention through Population wide Dietary SaltReduction: Protocol for population level sodium determination in 24 hours urine samples. Geneva: 2010. https://www.paho.org/hq/dmdocuments/2013/Final-Report-Regional-Expert-Group-Nov-2011-Eng.pdf.

World Health Organization. Global status report on noncommunicable diseases 2010. Geneva; 2011. https://www.who.int/nmh/publications/ncd_report_full_en.pdf.

Sarmugam R, Worsley A, Wang W. An examination of the mediating role of salt knowledge and beliefs on the relationship between socio-demographic factors and discretionary salt use: a cross-sectional study. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2013;10(1):25–33.

Abah IO, Dare BM, Jimoh HO. Hypertension prevalence, knowledge, attitude & awareness among pharmacists in Jos, Nigeria. West Afr. J. Pharm. 2014;25(2):98–106.

Oliveria SA, Chen RS, McCarthy BD, Davis CC, Hill MN. Hypertension knowledge, awareness, and attitudes in a hypertensive population. Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(3):219–25.

Addo J, Amoah AG, Koram KA. The changing patterns of hypertension in Ghana: a study of four rural communities in the Ga district. Ethn Dis. 2006;16(4):894–9.

Kusuma YS, Gupta SK, Pandav CS. Knowledge and perceptions about hypertension among settled migrants in Delhi, India. CVD Prev Control. 2009;4(2):119–29.

Demaio AR, Otgontuya D, De Courten M, Bygbjerg IC, Enkhtuya P, Meyrowitsch DW, et al. Hypertension and hypertension-related disease in Mongolia; findings of a national knowledge, attitudes and practices study. BMC Public Health. 2013;13(1):194.

So A, Kurmi R. Awareness, practices, and prevalence of hypertension among rural Nigerian women. Arch Med Health Sci. 2014;2(1):23–8.

Bollu M, Nalluri K, Prakash A, Lohith M, Venkataramarao N. Study of knowledge, attitude and practice of general population of Guntur toward silent killer disease: hypertension and diabetes. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2015;8(4):74–8.

Rahman M, Alam S, Mia M, Haque M, Islam K. Knowledge, attitude and practice about hypertension among adult people of selected areas of Bangladesh. MOJ Public Health. 2018;7(4):211–4.

Addo J, Smeeth L, Leon DA. Hypertension in sub-saharan Africa: a systematic review. Hypertension. 2007;50(6):1012–8.

Musinguzi G, Nuwaha F. Prevalence, awareness and control of hypertension in Uganda. PLoS One. 2013;8(4):e62236.

Raja TK, Muthukumar T, Anisha M. A cross sectional study on prevalence of hypertension and its associated risk factors among rural adults in Kanchipuram district, Tamil Nadu. Int J Community Med Public Health. 2018;5(1):249–54.

Institute for Public Health. National Health and Morbidity Survey 2011 (NHMS 2011). Vol II: non-communicable diseases. Kuala Lumpur: Ministry of Health Malaysia; 2011.

Olack B, Wabwire-Mangen F, Smeeth L, Montgomery JM, Kiwanuka N, Breiman R. Risk factors of hypertension among adults aged 35-64 years living in an urban slum Nairobi, Kenya. BMC Public Health. 2015;15(1):1251.

Pandit AU, Tang JW, Bailey SC, Davis TC, Bocchini MV, Persell SD, et al. Education, literacy, and health: mediating effects on hypertension knowledge and control. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;75(3):381–5.

Kilic M, Uzuncakmak T, Ede H. The effect of knowledge about hypertension on the control of high blood pressure. Int J Cardiovasc Acad. 2016;2(1):27–32.

Land M-A, Webster J, Christoforou A, Johnson C, Trevena H, Hodgins F, et al. The association of knowledge, attitudes and behaviours related to salt with 24-hour urinary sodium excretion. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2014;11:47. https://doi.org/10.1186/1479-5868-11-47.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the Director General of Health Malaysia for permission to publish this paper. Appreciation goes to the Department of Statistics, Malaysia, in the sampling process. Acknowledgement also goes to the Ministry of Health Malaysia (Nutrition Division, Non-Communicable Disease Section, State Health Departments, Liaison Officers and Scouts) in the preparation and during the data collection. Our sincere appreciation also goes to all participants and data collectors.

About this supplement

This article has been published as part of Journal of Health, Population and Nutrition Volume 40 Supplement 1, 2021: Malaysian Community Salt Survey 2017-2018 (MyCoSS). The full contents of the supplement are available online at https://jhpn.biomedcentral.com/articles/supplements/volume-40-supplement-1.

Funding

Publication costs are funded by the Newton-Ungku Omar Fund: UK–Malaysia Bilateral Health Research Collaboration for Non-Communicable Diseases with the grant number of MR/P012590/1 (joint funding from the Academy of Sciences Malaysia, Malaysian Industry-Government Group for High Technology and the Medical Research Council, UK). The funders had no role in the study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation or writing of the article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RA, FJH, FO, CSM, VM, NAMZ, SMS, LP and NSAA were responsible for the concept and project development. RA and FO supervised the project’s progress. RA and FJH designed the outline of the manuscript. RA, FJH and FO were responsible for the concept and project development. AB designed the outline of the manuscript and constructed the draft manuscript. SSG analysed the data. All authors contributed to the preparation and approval of the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approvals for the study were obtained from the Medical Research Ethics Committee (MREC), Ministry of Health Malaysia (NMRR-17-423-34969) and Queen Mary (University of London) Research Ethics Committee (QMERC2017/14) prior to conducting the study. Informed written consent was collected from all respondents at the beginning of the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Baharudin, A., Ambak, R., Othman, F. et al. Knowledge, attitude and behaviour on salt intake and its association with hypertension in the Malaysian population: findings from MyCoSS (Malaysian Community Salt Survey). J Health Popul Nutr 40 (Suppl 1), 6 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41043-021-00235-0

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41043-021-00235-0