Abstract

Background

Human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-DR is a classical major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II molecule encoded by five genes: HLA-DRA, HLA-DRB1, HLA-DRB3, HLA-DRB4 and HLA-DRB5. The current study aimed to investigate the role of these genes in gliomas by analyzing microarray data.

Methods

We enrolled 305 patients with histologically confirmed gliomas, and performed microarray data analysis along with studying their clinical characteristics. A new variable, termed HLA-DR score, was defined to explain the expression information of all five HLA-DR genes by factor analysis. HLA-DR scores in each grade of glioma and normal brain tissue were compared using one-way ANOVA. Lastly, correlations of HLA-DR scores with progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) were analyzed with Kaplan-Meier and Cox analysis.

Results

Our study indicated that an increased HLA-DR score, i.e. overexpression of HLA-DR genes, was correlated with a more aggressive glioma tumor grade (p < 0.001, One-way ANOVA). Moreover, the HLA-DR score was significantly higher in astrocytic tumors than oligodendroglial tumors (−0.718 ± 3.177 versus −2.975 ± 2.662, t-test) in low-grade gliomas (LGGs). Kaplan-Meier analysis of both PFS (p = 0.046, log-rank test; p = 0.021, Breslow test) and OS (p = 0.029, Breslow test) showed significant differences in the clinical outcomes between LGG patients with high versus low HLA-DR scores. Finally, the HLA-DR score was further identified to be an independent prognostic factor of clinical outcomes by multivariate analysis (p = 0.042 and p = 0.025, for PFS and OS, respectively) in LGG patients.

Conclusion

Expression of HLA-DR genes can be used to predict the tumor grade in gliomas, and the histological subtype in LGG. Furthermore, they are also an independent predictor for LGG patient survival.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Glioma, which accounts for approximately 81% of all primary malignant brain tumors, is the most common and aggressive form of primary brain cancer in adults [1, 2]. According to the World Health Organization (WHO) classification [3], gliomas can be classified into four grades based on histopathological criteria: WHO grade I are often benign and curable with gross total resection; WHO grade II and grade III gliomas often display more aggressive biological behaviors and eventually progress to high grade malignancies; and WHO grade IV tumors, also referred to as glioblastomas (GBMs), are the most frequent and lethal form. Despite current treatments, the median survival of patients with GBMs remains dismal [4]. Additionally, gliomas can also be classified as either astrocytic tumors or oligodendroglial tumors, based on their histopathological appearance [3]. In recent decades, there has been a substantial increase in the general understanding of glioma development and progression. However, there are still many issues which need further investigation, including the role of the host immune system in glioma development/biology.

Tumor-related immune surveillance evasion, and host immune suppression, have been widely accepted as typical characteristics of human cancers, but how the host immune system affects tumor development and progression has remained a challenge in the field of immunology [5, 6]. In this context, Schreiber et al. have first proposed the concept of cancer immunoediting, and suggested that the immune system played a dual role in cancer development and progression, i.e. in both the suppression and promotion of cancer [7, 8]. Gliomas is a disease carries profound genomic alterations, and a variety of tumor-specific genetic changes have been identified as prognostic indicators and/or therapeutic targets in glioma [9,10,11]. However, there are few papers regarding the roles of immune-related genetic changes in gliomas [12].

The human major histocompatibility complex (MHC), i.e. human leukocyte antigen (HLA), comprises of a set of genes which play an essential role in immune modulation. It is a 4000 kb gene complex on chromosome 6 [13], and can be divided into three groups based on the DNA sequence: HLA class I, HLA class II, and HLA class III. Aberrant expression of HLA genes has been identified in many human cancers. For instance, overexpression of HLA-G (subtype of HLA class I) has been demonstrated in various human malignancies, such as melanoma, breast cancer, and ovarian cancer [14,15,16,17]. Moreover, correlation of HLA-G overexpression with poor prognosis in low-grade gliomas (LGGs) has also been demonstrated previously by our group [18].

HLA-DR is a classical MHC class II molecule, with a αβ heterodimer anchored in the membrane. Its genetics are complex, and it is encoded by several genes with different functions. The α-chain is encoded by the HLA-DRA gene, while the β-chain is mainly encoded by 4 genes, including HLA-DRB1, HLA-DRB3, HLA-DRB4 and HLA-DRB5 [19]. Recently, a study reported that glioma patients with high HLA-DR expression had a significantly lower survival rate [20]. This finding was unanticipated and piqued our interest. As HLA-DR has been known as the antigen which is most responsible for graft loss during the first 6 months, whereas HLA-B is more important during the first 2 years, and HLA-A is associated with long-term survival [21]. Overexpression of these molecules is supposed to increase tumor immunogenicity, and thus slow or even prevent tumor growth. However, this study suggested otherwise and showed that overexpression of HLA-DR led to decreased survival in glioma patients [20]. Additionally, this study had some limitations, such as a small cohort of 60 patients, and the survival analysis was performed in patients with all grades of gliomas grouped together. In our view, the conclusions of this study may not accurately reflect the differences of HLA-DR distribution in different glioma grades. Thus, in this study we aimed to assess the mRNA expression levels of five HLA-DR genes using a large cohort, and specifically explore their potential correlation with the clinical outcome in gliomas of each grade.

Methods

Study population

A total of 305 patients who had undergone neurosurgical operations at Beijing Tiantan Hospital were enrolled. All patients had histological confirmation of gliomas along with mRNA microarray analysis. Histopathologic evaluation was performed independently by two experienced neuropathologists [3]. The clinical information of all patients was collected from the Chinese Glioma Genome Atlas database (http://www.cgga.org.cn). Among 305 patients, only six were lost in follow-up evaluation, and no patient deaths were recorded due to other diseases or unexpected events. The average follow-up length was 42.8 ± 35.5 months (median, 27.4 months; range, 0.7-111.4 months). In addition, tissue from five normal brains were surgically resected from trauma patients for use as negative controls. The present study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Beijing, Tiantan Hospital.

RNA extraction and whole genome gene profiling

RNA isolation and microarray analysis was carried out as previously described [22]. Briefly, tissue samples from patients were immediately snap frozen in liquid nitrogen following resection, and stored at −80 °C. Later, the frozen tumor samples were processed, and assessed based on cell morphology following hematoxylin and eosin-staining. Samples containing more than 20% of normal cells were excluded from RNA extraction to reduce the effects of contamination. Total RNA was isolated using MirVana miRNA Isolation kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, USA). Subsequently, quantification of exacted total RNA was performed with a NanoDrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies, Wilmington, USA).

The microarray data analysis was performed using an Agilent Whole Human Genome Array (Agilent, California, USA). First, an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer was used to determine total RNA integrity, then cDNA and biotinylated cRNA were isolated from the total RNA and hybridized onto microarrays. Next, the Agilent G2565BA Microarray Scanner System and Agilent Feature Extraction Software were used for data acquisition. The normalization of probe intensity was performed with Gene Spring GX 11.0 software.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using the IBM SPSS software, version 19.0. Continuous data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD), and a p value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. First, the mRNA expression of five HLA-DR genes in gliomas of each grade and normal brain tissue were compared using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Next, to evaluate the consistency of HLA-DR gene expression trends, a Pearson correlation matrix was created, and the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO, criterion: > 0.5) and Bartlett’s test for sphericity (criterion: p < 0.05) were used to test the adequacy of the correlation matrix. To eliminate the interference of multicollinearity, a second factor analysis was performed to define the new variable, which can represent the expression characteristics of the entire HLA-DR gene group. Patients with different tumor grades were classified into two subgroups for further analysis, based on their values of the defined variable (cut off at 50% of the entire group). Univariate analysis was carried out with the chi-square test for dichotomous variables. The log-rank test and Breslow test were both used to explore correlations of the defined variable with progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) in each glioma grade. PFS was defined as time from surgical resection until tumor recurrence (diagnosed by magnetic resonance (MR) imaging) or date of last follow-up, while OS was defined as the time from surgical resection until death or date of last follow-up. Finally, a Cox proportional hazards model was used to generate the multivariate model that described the correlation of prognostic factors with clinical outcomes.

Results

Patient characteristics

Among the 305 glioma patients enrolled in the current study, 126 were characterized as LGGs, 51 as anaplastic gliomas (AGs), and 128 as GBMs, according to the 2007 WHO classification. Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of the cohort.

Expression of five HLA-DR genes in gliomas

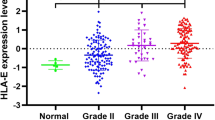

First, the mRNA expression levels of HLA-DR genes between normal brain tissue and gliomas of each grade were assessed using one-way ANOVA. Significant differences were observed in the mRNA expression of all five HLA-DR genes among normal brain tissues and different grades of gliomas (Fig. 1, p < 0.001 for all five HLA-DR genes, One-way ANOVA). Moreover, overexpression of those genes was associated with higher tumor grade (Fig. 1, normal brain tissue < LGGs < AGs < GBMs, mean). The expression of all five HLA-DR genes in normal brain tissue have been summarized in Additional file 1: Table S1.

Factor analysis and HLA-DR score calculation

Next, the consistency of HLA-DR gene expression in all 310 samples was confirmed by Pearson correlation analysis and the correlation matrix shown in Table 2. This correlation matrix in combination with a KMO index of 0.867 and a p-value less than 0.001 in the Bartlett test was appropriate for factor analysis, which was performed to avoid multicollinearity issues in regression analysis. The results are summarized in Table 3, and the Gravel Map (Fig. 2) indicated that the cumulative contribution rate of the first principal component eigenvalue is 94.952% for the total variance.

Under normal circumstances, when the cumulative contribution eigenvalue of the first k principal component is over 85%, there is enough information of all the original factors. Therefore, the information provided by the first component in our analysis was equivalent and representative of the entire HLA-DR gene group, and we defined it as the HLA-DR score. According to the component score coefficient matrix, the factor score of each HLA-DR gene was calculated (Table 4). Finally, the detailed method to determine the HLA-DR score was as follows:

Analysis of HLA-DR score in different grades of gliomas

The HLA-DR scores were compared in gliomas from different grades and normal brain tissue (Fig. 3). There was a significant difference (p < 0.001, One-way ANOVA) in HLA-DR scores between test groups, and higher HLA-DR scores were associated with increased tumor grade. Next, patients with different tumor grades were further divided into two subgroups according to their HLA-DR score. A chi-square test was subsequently used to analyze the associations between the HLA-DR scores and clinicopathological features (Table 5). A significant association was observed between the HLA-DR score and histological subtype of LGG (p < 0.001, chi-square test). Subsequently, a Student’s t-test was used to further analyze these associations, and we observed that in LGGs, the HLA-DR score in astrocytic tumors was significantly higher compared to oligodendroglial tumors (−0.718 ± 3.177 versus −2.975 ± 2.662, p < 0.001, t-test; Fig. 4).

Comparison of HLA-DR scores between low-grade glioma (LGG) tumor samples with different histological subtypes. The astrocytic tumors displayed an average HLA-DR score of −0.718 ± 3.177, while oligodendroglial tumors displayed an average of −2.975 ± 2.662. The difference was significant between the two subtypes (p < 0.001, t-test)

Correlation of HLA-DR score with glioma patient survival

Finally, the correlations of the HLA-DR score with clinical outcomes were examined using Kaplan-Meier analysis. The mean follow-up time was 42.8 ± 35.5 months (median, 27.4 months; range, 0.7-111.4 months) and 176 patients died (60.8% males) during the follow-up time. For PFS, significant differences (p = 0.046, log-rank test; p = 0.021, Breslow test; Fig. 5a) were found in LGG patients when high and low HLA-DR scores were compared. However, for OS, the Breslow test showed significance between the two subgroups (p = 0.029, Fig. 5b), while the log-rank test did not confirm this difference (p = 0.053, Fig. 5b). Based on this, we further analyzed the correlations of the HLA-DR score with clinical outcomes in astrocytic and oligodendroglial tumors. For patients with oligodendroglial tumors, a low HLA-DR score was associated with significantly improved PFS (p = 0.023, log-rank test; p = 0.024, Breslow test; Fig. 5c) and OS (p = 0.020, log-rank test; p = 0.021, Breslow test; Fig. 5d). For patients with astrocytic tumors, a low HLA-DR score also seemed to indicate better survival, but these data were not statistically significant (Fig. 5e and f). Overall, LGG patients with low HLA-DR scores appeared to have a better clinical outcome. In contrast, no significant difference was found in either PFS or OS between AG and GBM patients with high and low HLA-DR scores (Additional file 1: Figure S1).

Kaplan-Meier survival analysis. a Comparison of the PFS between high and low HLA-DR score groups in patients with LGGs (p = 0.046, log-rank test; p = 0.021, Breslow test). b Comparison of the OS between the two groups in patients with LGGs (p = 0.053, log-rank test; p = 0.029, Breslow test). c Comparison of the PFS between the two groups in patients with LGG oligodendroglial tumors (p = 0.023, log-rank test; p = 0.024, Breslow test). d Comparison of the OS between the two groups in patients with LGG oligodendroglial tumors (p = 0.020, log-rank test; p = 0.021, Breslow test). e Comparison of the PFS between the two groups in patients with LGG astrocytic tumors (p = 0.377, log-rank test; p = 0.078, Breslow test). f Comparison of the OS between the two groups in patients with LGG astrocytic tumors (p = 0.205, log-rank test; p = 0.092, Breslow test). PFS Progression-free survival; OS overall survival; LGG low-grade glioma

Furthermore, we also performed multivariate progression analysis to evaluate the independent value of the HLA-DR score and other variables for predicting PFS and OS in patients with LGGs. The HLA-DR score was enrolled into the Cox model as a continuous variable, and we observed the HLA-DR score to be an independent predictor of patient survival for LGGs (p = 0.042 and p = 0.025 for PFS and OS, respectively; Table 6).

Discussion

HLA-DR is the most abundant form of MHC class II antigens and it can inhibit tumor growth through two possible mechanisms. In the first immunological mechanism, HLA-DR contributes to the recognition of tumor-associated antigens by CD4+ T cells, which subsequently produce specific cytokines, such as interleukins and interferon-γ, which eventually results in tumor suppression [23]. The second mechanism is non-immunological, where HLA-DR is directly involved in the regulation of antitumor action by interferon-γ [24]. Overexpression of HLA-DR has been demonstrated in a variety of human malignancies including thyroid carcinoma, gastric carcinoma, colorectal cancer and cervical cancer [25,26,27,28]. However, in other tumors like breast cancer and ovarian cancer, HLA-DR was found to be downregulated, and correlated with immune response evasion and tumor aggressiveness [29,30,31]. These results suggested that the regulatory mechanisms of HLA-DR differed among different types of cancers.

It has been indicated by neuro-immunologists that HLA-DR antigens are expressed on glioma cells [32]. One study has reported that MHC class II antigens, mainly HLA-DR and DQ, are important for lymphocyte response, and transfection of these genes could increase the immunogenicity of glioma cells [33]. Consistently, we also observed higher mRNA expression of five HLA-DR genes that were linked with increased tumor grade. In addition, the HLA-DR score, which defined the expression of all HLA-DR genes, showed that a higher value was correlated with an increased tumor grade. Interestingly, we also observed that astrocytic tumors, which are the more aggressive histological subtype of LGGs, had a significantly higher HLA-DR score in comparison to oligodendroglial tumors.

The relationship of HLA-DR expression with patient survival in cancer was first described in large bowel carcinoma in 1993, where strong HLA-DR expression was correlated with good prognosis [34]. Since then, multiple studies in many cancers (colorectal, gastric and breast) showed a similar pattern, where tumors that were HLA-DR positive had a better prognosis [26, 28, 35]. However, our data in glioma patients was conflicting with these observations, as the glioma patients with high HLA-DR scores, i.e. high mRNA expression of HLA-DR genes, had a poor clinical outcome. Furthermore, the HLA-DR score was demonstrated to be an independent predictor for survival of LGG patients. A previous study that analyzed the protein levels of HLA-DR in glioma patients was consistent with our result [20].

Here seemed to be a contradiction. Theoretically, tumors with higher HLA-DR expression should show stronger immunogenicity, thus appear to be less aggressive and have a better prognosis. However, according to the current study, gliomas with high HLA-DR scores were precisely those with poor immunogenicity, few characterized cancer antigens, and more invasive characteristics [36], and in LGGs, patients with high HLA-DR scores had a poor survival rates. This contradictory observation regarding the correlation of a high HLA-DR score with poor clinical outcome can be attributed to the complex mechanisms of glioma immunogenicity, which have only been partially elucidated. Despite HLA-DR playing a role in shaping tumor immunogenicity, we speculate that the positive effects have been offset by much stronger negative effects. For instance, at least two principle HLA-related mechanisms of immune escape have been proposed. One is associated with overexpression of HLA-G, which we have previously demonstrated and has been found to contribute to GBM immune escape [18, 37]. The second is the complete loss or downregulation of classical HLA class I molecules, which we need to investigate further, but has been reported in other cancers [38]. Moreover, we cannot rule out the possibility of other specific yet unknown mechanisms involved in enhancing/decreasing the immunogenicity of gliomas.

In recent years, immunotherapy has become one of the major options for anti-cancer therapy. Based on the results of our survival analysis, we may initially extrapolate to determine the type of glioma patient suitable to receive immunotherapy. Our survival analysis results suggested no significant difference in the prognosis of subgroups with high and low HLA-DR scores in AGs or GBMs patients. This can be explained by the fact that the interaction between the immune system and tumor is a relatively slow process, and the rapid progression of these high-grade gliomas did not allow the immune system enough time to exert its influence. Therefore, the efficacy of immunotherapy may be limited in patients with high-grade gliomas. In addition, it has been reported that several months of Bacille Calmette-Guerin (BCG) immunotherapy, could induce a strong level of HLA-DR expression in bladder cancer [39]. Another study showed that BCG-treated patients with absent or low expression of HLA-DR had a prolonged disease-free survival in melanoma [40]. Accordingly, immunotherapy may show better efficacy on LGG patients with low HLA-DR expression.

Conclusion

In the current study, data from 305 patients having histologically confirmed gliomas were retrospectively analyzed, and we observed that the mRNA expression levels of five HLA-DR genes were higher in different grades of gliomas compared to normal brain tissue. In addition, we defined a new variable, termed the HLA-DR score, to represent the expression of the entire HLA-DR gene group. We observed that a higher HLA-DR score was correlated with both the higher tumor grade in gliomas and the more aggressive histological type in LGG. Furthermore, the HLA-DR score was also an independent predictive factor of clinical outcomes in LGG patients. Considering the complex interaction between the HLA system and gliomas, these results are just the tip of the iceberg. Further investigation into the roles of other HLA molecules in gliomas are still required, and these studies may further reveal the interaction between gliomas and the immune system.

Abbreviations

- AG:

-

Anaplastic glioma

- GBM:

-

Glioblastoma

- HLA:

-

Human leukocyte antigen

- LGG:

-

Lower-grade glioma

- MHC:

-

Major histocompatibility complex

- OS:

-

Overall survival

- PFS:

-

Progression-free survival

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Ohgaki H, Kleihues P. Epidemiology and etiology of gliomas. Acta Neuropathol. 2005;109(1):93–108. doi:10.1007/s00401-005-0991-y.

Ostrom QT, Bauchet L, Davis FG, Deltour I, Fisher JL, Langer CE, Pekmezci M, Schwartzbaum JA, Turner MC, Walsh KM, Wrensch MR, Barnholtz-Sloan JS. The epidemiology of glioma in adults: a “state of the science” review. Neuro-Oncology. 2014;16(7):896–913. doi:10.1093/neuonc/nou087.

Louis DN, Ohgaki H, Wiestler OD, Cavenee WK, Burger PC, Jouvet A, Scheithauer BW, Kleihues P. The 2007 WHO classification of tumours of the central nervous system. Acta Neuropathol. 2007;114(2):97–109. doi:10.1007/s00401-007-0243-4.

Stupp R, Mason WP, van den Bent MJ, Weller M, Fisher B, Taphoorn MJ, Belanger K, Brandes AA, Marosi C, Bogdahn U, Curschmann J, Janzer RC, Ludwin SK, Gorlia T, Allgeier A, Lacombe D, Cairncross JG, Eisenhauer E, Mirimanoff RO, European Organisation for R, Treatment of Cancer Brain T, Radiotherapy G, National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials G. Radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide for glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(10):987–96. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa043330.

Vesely MD, Kershaw MH, Schreiber RD, Smyth MJ. Natural innate and adaptive immunity to cancer. Annu Rev Immunol. 2011;29:235–71. doi:10.1146/annurev-immunol-031210-101324.

Vesely MD, Schreiber RD. Cancer immunoediting: antigens, mechanisms, and implications to cancer immunotherapy. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2013;1284:1–5. doi:10.1111/nyas.12105.

Manjili MH. Revisiting cancer immunoediting by understanding cancer immune complexity. J Pathol. 2011;224(1):5–9. doi:10.1002/path.2865.

Schreiber RD, Old LJ, Smyth MJ. Cancer immunoediting: integrating immunity's roles in cancer suppression and promotion. Science. 2011;331(6024):1565–70. doi:10.1126/science.1203486.

Yan H, Parsons DW, Jin G, McLendon R, Rasheed BA, Yuan W, Kos I, Batinic-Haberle I, Jones S, Riggins GJ, Friedman H, Friedman A, Reardon D, Herndon J, Kinzler KW, Velculescu VE, Vogelstein B, Bigner DD. IDH1 and IDH2 mutations in gliomas. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(8):765–73. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0808710.

Eckel-Passow JE, Lachance DH, Molinaro AM, Walsh KM, Decker PA, Sicotte H, Pekmezci M, Rice T, Kosel ML, Smirnov IV, Sarkar G, Caron AA, Kollmeyer TM, Praska CE, Chada AR, Halder C, Hansen HM, McCoy LS, Bracci PM, Marshall R, Zheng S, Reis GF, Pico AR, O'Neill BP, Buckner JC, Giannini C, Huse JT, Perry A, Tihan T, Berger MS, Chang SM, Prados MD, Wiemels J, Wiencke JK, Wrensch MR, Jenkins RB. Glioma groups based on 1p/19q, IDH, and TERT promoter mutations in Tumors. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(26):2499–508. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1407279.

Zacher A, Kaulich K, Stepanow S, Wolter M, Kohrer K, Felsberg J, Malzkorn B, Reifenberger G. Molecular diagnostics of gliomas using next generation sequencing of a glioma-tailored gene panel. Brain Pathol. 2016. doi:10.1111/bpa.12367.

Vauleon E, Tony A, Hamlat A, Etcheverry A, Chiforeanu DC, Menei P, Mosser J, Quillien V, Aubry M. Immune genes are associated with human glioblastoma pathology and patient survival. BMC Med Genet. 2012;5:41. doi:10.1186/1755-8794-5-41.

Klein J, Sato A. The HLA system. First of two parts. N Engl J Med. 2000;343(10):702–9. doi:10.1056/NEJM200009073431006.

Ugurel S, Rebmann V, Ferrone S, Tilgen W, Grosse-Wilde H, Reinhold U. Soluble human leukocyte antigen--G serum level is elevated in melanoma patients and is further increased by interferon-alpha immunotherapy. Cancer. 2001;92(2):369–76.

Jeong S, Park S, Park BW, Park Y, Kwon OJ, Kim HS. Human leukocyte antigen-G (HLA-G) polymorphism and expression in breast cancer patients. PLoS One. 2014;9(5):e98284. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0098284.

Ben Amor A, Beauchemin K, Faucher MC, Hamzaoui A, Hamzaoui K, Roger M. Human leukocyte antigen G polymorphism and expression are associated with an increased risk of non-small-cell lung cancer and advanced disease stage. PLoS One. 2016;11(8):e0161210. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0161210.

Andersson E, Poschke I, Villabona L, Carlson JW, Lundqvist A, Kiessling R, Seliger B, Masucci GV. Non-classical HLA-class I expression in serous ovarian carcinoma: correlation with the HLA-genotype, tumor infiltrating immune cells and prognosis. Oncoimmunology. 2016;5(1):e1052213. doi:10.1080/2162402X.2015.1052213.

Fan X, Wang Y, Zhang C, Liu X, Qian Z, Jiang T. Human leukocyte antigen-G overexpression predicts poor clinical outcomes in low-grade gliomas. J Neuroimmunol. 2016;294:27–31. doi:10.1016/j.jneuroim.2016.03.015.

Marsh SG, Albert ED, Bodmer WF, Bontrop RE, Dupont B, Erlich HA, Geraghty DE, Hansen JA, Hurley CK, Mach B, Mayr WR, Parham P, Petersdorf EW, Sasazuki T, Schreuder GM, Strominger JL, Svejgaard A, Terasaki PI, Trowsdale J. Nomenclature for factors of the HLA system, 2004. Tissue Antigens. 2005;65(4):301–69. doi:10.1111/j.1399-0039.2005.00379.x.

Diao J, Xia T, Zhao H, Liu J, Li B, Zhang Z. Overexpression of HLA-DR is associated with prognosis of glioma patients. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015;8(5):5485–90.

Solomon S, Pitossi F, Rao MS. Banking on iPSC--is it doable and is it worthwhile. Stem Cell Rev. 2015;11(1):1–10. doi:10.1007/s12015-014-9574-4.

Wang Y, Fan X, Li H, Lin Z, Bao H, Li S, Wang L, Jiang T, Fan Y, Jiang T. Tumor border sharpness correlates with HLA-G expression in low-grade gliomas. J Neuroimmunol. 2015;282:1–6. doi:10.1016/j.jneuroim.2015.02.013.

Armstrong TD, Clements VK, Ostrand-Rosenberg S. Class II-transfected tumor cells directly present endogenous antigen to CD4+ T cells in vitro and are APCs for tumor-encoded antigens in vivo. J Immunother. 1998;21(3):218–24.

Dredge K, Marriott JB, Todryk SM, Dalgleish AG. Adjuvants and the promotion of Th1-type cytokines in tumour immunotherapy. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2002;51(10):521–31. doi:10.1007/s00262-002-0309-z.

Sridama V, Hara Y, Fauchet R, DeGroot LJ. Association of differentiated thyroid carcinoma with HLA-DR7. Cancer. 1985;56(5):1086–8.

Hilton DA, West KP. An evaluation of the prognostic significance of HLA-DR expression in gastric carcinoma. Cancer. 1990;66(6):1154–7.

Madeleine MM, Brumback B, Cushing-Haugen KL, Schwartz SM, Daling JR, Smith AG, Nelson JL, Porter P, Shera KA, McDougall JK, Galloway DA. Human leukocyte antigen class II and cervical cancer risk: a population-based study. J Infect Dis. 2002;186(11):1565–74. doi:10.1086/345285.

Matsushita K, Takenouchi T, Shimada H, Tomonaga T, Hayashi H, Shioya A, Komatsu A, Matsubara H, Ochiai T. Strong HLA-DR antigen expression on cancer cells relates to better prognosis of colorectal cancer patients: possible involvement of c-myc suppression by interferon-gamma in situ. Cancer Sci. 2006;97(1):57–63. doi:10.1111/j.1349-7006.2006.00137.x.

Tamiolakis D, Kotini A, Venizelos J, Jivannakis T, Simopoulos C, Papadopoulos N. Prognostic significance of HLA-DR antigen in serous ovarian tumors. Clin Exp Med. 2003;3(2):113–8. doi:10.1007/s10238-003-0013-0.

da Silva GB, Silva TG, Duarte RA, Neto NL, Carrara HH, Donadi EA, Goncalves MA, Soares EG, Soares CP. Expression of the classical and nonclassical HLA molecules in breast cancer. Int J Breast Cancer. 2013;2013:250435. doi:10.1155/2013/250435.

Huang A, Zhang B, Wang B, Zhang F, Fan KX, Guo YJ. Increased CD14(+)HLA-DR (−/low) myeloid-derived suppressor cells correlate with extrathoracic metastasis and poor response to chemotherapy in non-small cell lung cancer patients. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2013;62(9):1439–51. doi:10.1007/s00262-013-1450-6.

Piguet V, Diserens AC, Carrel S, Mach JP, de Tribolet N. The immunobiology of human gliomas. Springer Semin Immunopathol. 1985;8(1-2):111–27.

Yoshida S, Takahashi H, Tanaka R. Expression of MHC class II antigens on human glioma cells modulated by transfection with genes encoding these antigens. Neurol Med Chir. 1991;31(10):623–8.

Andersen SN, Rognum TO, Lund E, Meling GI, Hauge S. Strong HLA-DR expression in large bowel carcinomas is associated with good prognosis. Br J Cancer. 1993;68(1):80–5.

Sheen-Chen SM, Chou FF, Eng HL, Chen WJ. An evaluation of the prognostic significance of HLA-DR expression in axillary-node-negative breast cancer. Surgery. 1994;116(3):510–5.

Cohen-Inbar O, Zaaroor M. Immunological aspects of malignant Gliomas. Can J Neurol Sci. 2016;43(4):494–502. doi:10.1017/cjn.2016.34.

Wiendl H, Mitsdoerffer M, Hofmeister V, Wischhusen J, Bornemann A, Meyermann R, Weiss EH, Melms A, Weller M. A functional role of HLA-G expression in human gliomas: an alternative strategy of immune escape. J Immunol. 2002;168(9):4772–80.

Hicklin DJ, Marincola FM, Ferrone S. HLA class I antigen downregulation in human cancers: T-cell immunotherapy revives an old story. Mol Med Today. 1999;5(4):178–86.

Prescott S, James K, Busuttil A, Hargreave TB, Chisholm GD, Smyth JF. HLA-DR expression by high grade superficial bladder cancer treated with BCG. Br J Urol. 1989;63(3):264–9.

Brocker EB, Suter L, Czarnetzki BM, Macher E. BCG immunotherapy in stage I melanoma patients. Does it influence prognosis determined by HLA-DR expression in high-risk primary tumors? Cancer Immunol Immunother. 1986;23(2):155–7.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Yuling Yang for tissue sample collection and clinical data retrieval.

Availability of data and material

All data generated or analyzed in this study are included in this published article [and its Additional file 1].

Funding

This work was supported by funding from the National Key Research and Development Plan (No. 2016YFC0902500), and Beijing Science and Technology Plan (No. Z131100006113018).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conception and design: TJ, XF. Data collection: JL, ZW. Statistical analysis: XF, XS. Manuscript writing: XF. Critically revising the article: HQ. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

We declare that this study has been approved by the ethics committee of Beijing Tiantan Hospital, and has been performed in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors have no actual or potential conflicts of interest related to this manuscript.

Additional file

Additional file 1: Table S1.

Expression levels of the five HLA-DR genes in negative controls (5 normal brain samples). Figure S1. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis for patients with AGs and GBMs. (A) Comparison of the PFS between high HLA-DR scores and low HLA-DR scores in patients with AGs (p = 0.711, log-rank test; p = 0.865, Breslow test). (B) Comparison of the OS between high HLA-DR scores and low HLA-DR scores in patients with AGs (p = 0.838, log-rank test; p = 0.658, Breslow test). (C) Comparison of the PFS between high HLA-DR scores and low HLA-DR scores in patients with GBMs (p = 0.940, log-rank test; p = 0.947, Breslow test). (D) Comparison of the OS between high HLA-DR scores and low HLA-DR scores in patients with GBMs (p = 0.906, log-rank test; p = 0.651, Breslow test). AG, anaplastic gliomas; GBMs, glioblastomas. (DOC 108 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Fan, X., Liang, J., Wu, Z. et al. Expression of HLA-DR genes in gliomas: correlation with clinicopathological features and prognosis. Chin Neurosurg Jl 3, 27 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41016-017-0090-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41016-017-0090-7