Abstract

Companies’ communications about Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) have become increasingly prevalent yet psychological reasons for why those communications might lead to positive reactions of the general public are not fully understood. Building on theories on impression formation and social evaluation, we assess how CSR communications affect perceived morality and competence of a company. We theorize that the organization’s CSR activities would positively impact on perceived organizational morality rather than on perceived organizational competence and that this increase in perceived organizational morality leads to an increase in stakeholders’ support. Two experimental design studies show support for our theorizing. We cross-validated the robustness and generality of the prediction in two countries with different business practices (UK (N = 203), Russia (N = 96)). We demonstrated that while the general perceptions of companies and CSR differ between the UK and Russia, the underlying psychological mechanisms work in a similar fashion. By testing our predictions in western, educated, industrialized, rich, and democratic (WEIRD) and in non- WEIRD countries, we also extend current socio-psychological insights on the social evaluation of others. We discuss theoretical and practical implications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Introduction

Almost every day on the news people read about positive actions of various companies such as promoting diversity or working on environmentally friendly production solutions (Corporate Social Responsibility or CSR activities). People become increasingly aware of the importance of CSR including addressing environmental issues (Sabherwal et al., 2021). Corporate communications about those type of activities are increasingly prevalent and it became an important topic in academic research across different disciplines (e.g. Aguinis & Glavas, 2012). Will this affect your perceptions of the company and why? While there is a large body of evidence that suggests that you would be positively affected by such corporate communications, the reasons behind why this is the case are not fully understood (Aguinis & Glavas, 2012; Jamali & Karam, 2018; Simpson & Aprim, 2018).

In the present research, we address the identified research need and we contribute to the current literature in several ways. First, we apply the insights from Social Identity Theory (Tajfel, 1974; Tajfel & Turner, 1979, 1986) and theories on social evaluation of others (Abele et al., 2021; Abele & Wojciszke, 2007; Hack et al., 2013; Wojciszke et al., 1998) to explain the relationship between CSR activities and stakeholders’ reactions (i.e. reactions of actual or potential employees or customers of a company), thus extending prior micro- or individual level CSR literature (Aguinis & Glavas, 2019; Jamali & Karam, 2018). By applying theories of social evaluation to people’s assessments of companies, we extend the emerging theory on how people develop impressions of non-human subjects (Ashforth et al., 2020; Epley et al., 2007; Gawronski et al., 2018). Second, we provide empirical evidence to our theorizing by conducting experimental design studies in two countries (Russia and UK) with different business practices (e.g. Russia is ranked at the bottom of the corruption index offered by Transparency International (137 out of 180 countries), and the UK (12 out of 180)), which can impact on development and perceptions of CSR. We propose and demonstrate that while country-specific conditions can indeed influence both the types of CSR activities (Awuah, et al., 2021; Ervits, 2021) and stakeholders’ reactions to CSR activities (Grabner-Kräuter et al., 2020; Jamali & Karam, 2018), the socio-psychological mechanisms explaining the relationship between CSR and stakeholders’ support work in similar fashion in two countries with different business practices (Cuddy et al., 2009). Finally, in the social psychological and organizational behavior literature there are growing concerns about the potential lack of generalizability of study results, as most of the theory is supported by the empirical evidence obtained in Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, Democratic (WEIRD) countries (Cheon et al., 2020; Henrichet al., 2010b). This is particularly problematic since WEIRD-based research accounts for over 90% of the psychological research, while only 12% of the world lives in WEIRD countries (Henrich et al., 2010a). Thus, by explicitly testing our theorizing in both WEIRD and non-WEIRD samples, we extend current socio-psychological insights on the social evaluation of others.

Morality and competence as key dimensions for social evaluation of others

Individuals assess others on the basis of two key dimensions. Although different approaches have emphasized slightly different aspects of these dimensions and use different labels, the two key dimensions can generally be interpreted as referring to task ability (competence/agency) vs. interpersonal intentions (morality/communion/warmth) (Fiske et al., 2007; Goodwin et al., 2014; Leach et al., 2007; Wojciszke, 1994). We know that those key dimensions capture distinct behavioral features of various targets (Wojciszke, 1994).

Importantly, researchers have started to apply dimensions of social evaluation of other human targets to the emerging theory on how people develop impressions of non-human subjects such as companies and brands (Kervyn et al., 2012; Shea & Hawn, 2019). Similarly, we apply those two dimensions of social evaluation to people’s perceptions of companies, thus building on this latest trend in the organizational behavior literature to leverage on the findings from social psychology as people tend to anthropomorphize non-human targets, including organizations (Ashforth et al., 2020; Epley et al., 2007).

We know that, generally speaking, CSR activities imply that a company is focusing on something above and beyond of what is strictly speaking required by law (McWilliams & Siegel, 2001). One of the recognized key goals of the company is to make a profit. When organizations engage in CSR, this generally cannot be explained from profit-making motives, or from legal requirements. Examples of CSR activities include introducing additional measures to attract minority groups or better accommodating employees or customers with disabilities. Behaving responsibly is generally seen as ethical (Carroll, 2016; Mitnick et al., 2023) or ‘morally good’, and hence this might improve the perceived morality of a company. To date, the specific relationship between displays of CSR and perceptions of organizational morality, or perceived trustworthiness (Leach et al., 2015) of companies, has been proposed in mainly been established with survey-based studies (e.g., Ellemers et al., 2011; Farooq et al., 2014; Hillenbrand, et al., 2013). Accordingly, we would expect that learning about companies’ CSR activities would increase the perceived organizational morality of a company. We use experimental design studies that allow us to draw causal conclusions (Shadish et al., 2002), thus providing a strong test of our prediction. Our work speaks to the classic admonition that in research there is “no causation without manipulation” (Holland, 1986).

-

Hypothesis 1: Learning about companies’ CSR activities would increase the perceived organizational morality of a company.

Organizational morality as a source of stakeholders’ support

The fact that morality and competence, as two key dimensions of impression formation, account for over 80% of the variance in our impressions of others (Wojciszke et al., 1998), means that any information that would positively impact any of those two dimensions would result in a positive overall impression of other evaluative targets. Since we apply morality and competence to the evaluation of companies, this implies that any information about a company that would positively impact any of those two dimensions would result in a positive overall impression of a company or in the overall increase in stakeholders’ support for a company. In a business context, competence is clearly important. It seems evident that if a company is perceived more competent, for example, because it has better products than its competitors, then such a company would get more support from customers or would be better positioned to attract and retain employees. Why an increase in perceived organizational morality would also positively impact stakeholders’ support in a business context can be explained by Social Identity Theory (Tajfel, 1974; Tajfel & Turner, 1979, 1986).

Based on Social Identity Theory (Tajfel, 1974; Tajfel & Turner, 1979, 1986), it has been argued and shown that the perceived characteristics of an organization determine its subjective attractiveness, and drive the willingness of individuals to associate with that organization (Ashforth and Mael 1989; Ellemers et al., 2004; Haslam et al., 2009; Haslam et al., 2000). Furthermore, people tend to identify with companies not only as employees but also as consumers (Fennis & Pruyn, 2007; MacInnis & Folkes, 2017; Stokburger-Sauer et al., 2012; Tuškej et al., 2013). Over the years, research, inspired mostly by reasoning based on social identity theory, has demonstrated that morality is particularly important for our assessment of other people, especially when these others somehow relate to the self (Abele et al., 2021; Goodwin et al., 2014; Leach et al., 2007; Wojciszke et al., 1998). Recent theory posited that both employees and customers tend to evaluate companies by interpersonal standards (Ashforth et al., 2020). That means that since both employees and consumers tend to identify with companies – even in a business context – the perceived morality of an organization would have an impact on the evaluations of companies by both employees and customers. Moreover, perceptions of organizational morality have been found to be at least as important as perceptions of organizational competence in attracting and committing the support of relevant stakeholders (van Prooijen & Ellemers, 2015; van Prooijen et al., 2018). Thus, we propose that in business contexts as well, an increase in perceived organizational morality should lead to an increase in the desire to associate the self with the company i.e. to increased intentions to buy companies’ products or to work for a company. Since we argue that CSR activities enhance the perceived morality of the company (Hypothesis 1). We also propose that the perceived morality of the company should mediate the relationship between learning that a company is engaged in CSR activities and stakeholders’ support for this company.

-

Hypothesis 2: We predict that informing participants about CSR activities of a company should increase stakeholders’ support for that company.

-

Hypothesis 3: Perceived organizational morality is a mediator for the relationship between CSR activities and stakeholders’ support.

CSR perceptions in Russia

The examination of CSR in developing countries is an emerging field of study (Boubakri et al., 2021; Jamali & Mirshak, 2007; Khojastehpour & Jamali, 2021; Kolk & van Tulder, 2010). The economic and institutional differences between developing and developed countries raise questions about the applicability of some of the general CSR findings to emerging markets contexts and make this a topic worthy of investigation (Jamali & Karam, 2018). For example, prior work demonstrates that the differences in economic inequality can impact on how people behave in business contexts (König et al., 2020). Research shows that cultural traditions can impact on stakeholders’ reactions to CSR (Wang et al., 2018). Similarly, the differences in business practices related to different levels of perceived corruption between countries can result in differences in CSR approaches (Barkemeyer et al., 2018) or, which might mean that people have different views and different perceptions of CSR between a country with a relatively high level of corruption (e.g. Russia) and a country with a relatively low level of corruption (e.g. the UK).

Even within the limited research field focused on CSR in developing countries, some regions or countries have benefited from more attention than others. On a comparative basis, while in recent years CSR researchers have examined the situation in China and Africa, meriting even review research (Idemudia, 2011; Moon & Shen, 2010), CSR in the developing economies of Central and Eastern Europe and Russia in particular, which experienced radical redevelopment of economic and corporate governance systems (Aluchna et al., 2020; Tkachenko & Pervukhina, 2020) has attracted minimal research efforts. So far, not surprisingly, there is some evidence that the forms of CSR visible in Central and Eastern Europe and in Russia are affected by the historical socialist or central planning legacy (Fifka & Pobizhan, 2014; Koleva et al., 2010). For example, during Soviet times, in Russia, companies used to take care of their employees by providing kindergartens, health and recreation facilities, which was valuable to employees in the absence of public social security system (Fifka & Pobizhan, 2014). Thus, in the past, Russian companies were strong in, what can be considered as CSR activities towards their employees. On the other hand, historically, Russian companies did not view customers or clients as important stakeholders to consider in their business decisions and for CSR activities (Alon et al., 2010; Fifka & Pobizhan, 2014). While historical circumstances suggest that there might be differences in CSR approaches between the UK and Russia, the limited amount of available research does not reveal whether Russians perceive CSR differently than their UK-based counterparts. For example, one study, looking at the attitudes of Russian managers towards CSR, concluded that, in contrast to Western managers, Russian managers do not view CSR as a positive way to influence consumers’ perceptions about a company (Kuznetsov et al., 2009). On the other hand, a different line of research revealed that many Russian firms do provide some CSR information to external stakeholders (Preuss & Barkemeyer, 2011). This suggests that the managers of at least those companies think providing such information might somehow be beneficial for their companies.

In sum, the limited amount of research about CSR in Russia does not provide us with an answer to how the Russians would perceive CSR activities. Thus, we propose to turn to the insights about basic social psychological mechanisms that are likely to play a role across different countries and contexts, to inform our views about stakeholders’ perceptions of CSR activities in Russia.

We note that morality and competence are among the few social psychological concepts which were tested in multiple countries. In fact, some of the first conclusions about morality and competence were drawn based on Polish samples (Wojciszke, 1994; Wojciszke et al., 1998). These two dimensions were later tested in the US context (Cuddy et al., 2007; Fiske et al., 2002), in Dutch context (Leach et al., 2007) and in Polish and German settings (Abele & Wojciszke, 2007). An impressive cross-cultural collaboration showed the applicability of those two key dimensions across ten nations, including such countries as Spain, Germany, France, the UK, Japan, and South Korea (Cuddy et al., 2009).

While those dimensions have not yet been tested in Russia, we argue, based on the robust evidence for the cross-cultural relevance of those two dimensions of impression formation, that those dimensions should be equally applicable in both UK and Russian contexts. Thus, we propose that while there are multiple factors that could make the evaluation of CSR activities to be different between the UK and Russia (Jamali & Karam, 2018; Jamali & Mirshak, 2007), the psychological process at work would be the same as in the UK. Consequently, we argue that we will find support for our theorizing also in the Russian sample, providing further empirical support to our Hypotheses 1,2 and 3.

Current research

In two experimental studies, we assessed how CSR communications of a company affected perceived morality, perceived competence and stakeholders’ support for the company (as a customer or prospective employee). In both studies, we focused on evaluations of companies by the general public. Members of the general public are the key target, whom companies try to reach (e.g., as prospective clients, employees, or investors) by communicating about their CSR activities. Perceptions of the general public are shown to be a good predictor of key positive outcomes for companies (e.g. an increase in the shareholders’ value, Raithel & Schwaiger, 2015). In Study 1, we tested our hypotheses in the UK. In Study 2 (Russia), we replicated the results of Study 1. We cross-validated the robustness and generality of the relations we predicted between CSR, perceived morality and stakeholders’ support by examining whether this would hold across these two very different business contexts.

This research was pre-approved by the University’s Ethics Committee.

Study 1

Method

Participants and design

All participants for Study 1 were based in the UK and approached via Prolific. 249 participants completed the survey. We retained 203 participants (127 female), M age = 36 (SD = 12). M work experience = 15 (SD = 12), excluding participants who failed an attention check (participants were asked to tick a certain number and to select if they read about Company A or X). Please note we checked the results, including all participants who completed the questionnaire, and the main patterns remained the same.

Participants were randomly divided into two groups. Both groups received some neutral company information: “Company A is a mid-size IT advisory company based in the UK. It delivers websites, web-based IT systems, and computing as a service. It also provides information technology, research and consulting services.”

Thereafter, the control group proceeded directly to the dependent variables. The experimental condition group first read that the company was engaged in CSR activities (via a short press release about CSR activities). It was stated that Company A issued a CSR report detailing the company’s progress on environmental, social and governance initiatives. No specific reason for engaging in CSR activities was stated. After receiving this information and the participants proceeded to the dependent variables. Finally, all participants were thanked, debriefed and compensated.

Dependent variables

We assessed morality and competence with the items developed by (Leach et al., 2007). We have asked the participants to answer the following question: “We would like to get an impression of how you view Company A. Please have a look at the list of various traits and rank to what extent you view Company A as…” Items comprising this scale were presented to participants in a randomized order. Factor analysis confirmed that these items indicate morality and competence as two different constructs in line with (Leach et al., 2007):morality, 3 items: honest, trustworthy, sincere (ɑ = 0.91), competence, 3 items: intelligent, competent, skillful (ɑ = 0.86).

We evaluated support of various stakeholders such as clients and employees i.e. stakeholders’ support for a company using the following questions: ‘Please rate your intentions to buy products/services of Company A’, ‘Please imagine you can apply for a job in company A. Do you feel motivated to work for Company A?’ (ɑ = 0.81. The two items we used to evaluate the support of two key types of stakeholders’ such as potential customers/clients and potential employees. Those two types of stakeholders are often the focus of CSR research (e.g. Baskentli et al., 2019; Bauman & Skitka, 2012). We utilized a 7-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree), asking participants to indicate how well each of these items reflected their own position. Likert-type scale ranging from 1 to 7 was used to measure participants’ reactions in all studies unless stated otherwise.

Results

To guard against capitalization on chance, we conducted a MANOVA with communication about CSR activities of Company A (yes/no) as the between-subjects variable and morality, competence and stakeholders’ support, as dependent variables, which revealed a multivariate significant effect F (3,200) = 5.20, p = 0.002. We then examined univariate effects on morality, competence stakeholders’ support, separately.

Morality and competence

Consistent with Hypothesis 1, participants who read that Company A was engaged in CSR activities viewed Company A as more moral (morality M csr = 5.07 SD = 0.97) than participants who didn’t read anything about CSR activities of Company A (morality M no csr = 4.68, SD = 1.07), F (1, 202) = 7.70, p = 0.006. The effect of the experimental condition on competence was not significant F (1,202) = 0.02, p = 0.89. These results show that the experimental manipulation improved the perceived morality of the company. The fact that we did not find an effect of our experimental manipulation on perceived competence shows that CSR information does not just improve the general impression people have of the company. If that were the case, we would have expected improved perceptions of both morality and competence. This is not what we observed. Instead, our manipulation only improved the perceived morality of the company.

Stakeholders’ support

The univariate effect on stakeholders’ support was significant, F (1,202) = 5.54, p = 0.02. Consistent with Hypothesis 2, participants who read that Company A was engaged in CSR activities expressed higher stakeholder’ support for Company A (M csr = 5.14, SD = 1.04) than participants who didn’t read about CSR activities of Company A (M no csr = 4.76, SD = 1.23).

Mediation

We then assessed whether the effect of the experimental condition on the stakeholders’ support for Company A was mediated by the perceived morality. We were able to infer morality mediation thanks to the temporal order in our experimental design (Shea & Hawn, 2019). A mediation model analysis was conducted using PROCESS macro (Hayes, 2017) for SPSS based on 10,000 bootstrap resamples.

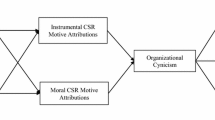

As is depicted in Fig. 1, communications about CSR activities indirectly influenced stakeholders’ support through its effect on the perceived morality of a company. The participants, who read about CSR activities, perceived Company A to be more moral and they also showed more support for the company. The confidence interval for the indirect effect was above 0. Thus, in line with predictions, the analysis provided support for our reasoning that morality (b = 0.286, SE = 0.108; CI = LL: 0.0.095; UL: 0.515, 10,000 bootstrap resamples), accounts for the relationship between CSR activities and stakeholders’ support. Thus, the results are consistent with Hypothesis 3, that morality mediates the relationship between CSR activities and stakeholders’ support.

Mediation model Study 1 c is total effect, it shows that there is an effect of X on Y that may be mediated. Path c' is called the direct effect. The mediator has been called an intervening or process variable. We can see that there is a mediation, as variable X no longer affects Y after M (perceived company’s morality) has been controlled, making path c' statistically non-significant

Study 2

Method

Participants and design

All participants in Study 2 were based in Russia. One of the co-authors approached Psychology and Applied Psychology students from a university, to participate in the research. One hundred eighteen participants completed the quantitative part of the study, out of which twenty-two participants failed the attention check, which asked participants to tick a certain number and to select if they read about Company A or X. When checking the results, including all participants, the main patterns remained the same. The final sample we used to analyze the quantitative data for this study consisted of 96 participants (80% female), M age = 21 (SD = 2.7), M work experience = 2 (SD = 2.9).

Similar to Study 1, participants were randomly assigned to the control and experimental groups. Both control and experimental groups received the same information as in Study 1; we only changed the description specifying that the company was a Russian company to fit this specific context. Participants in the experimental group read a short text about CSR and information about Company A being active in CSR, similar to Study 1 this was presented as a press release from Company A. Participants of both groups completed the dependent variables. The participants received no monetary compensation.

Dependent variables

Morality and Competence

We assessed perceptions of organizational morality (ɑ = 0.84) and competence (ɑ = 0.76) with items we use in Study 1 (Leach et al., 2007).

Stakeholders’ support

We decided to expand on the two items we used in Study 1 by adding two supplementary questions. We evaluated stakeholders’ support for the company with the following items: ‘Please imagine that you are a client of Company A. How likely is it that you would purchase Company A’s products?’, ‘How likely is it that you would want to recommend Company A’s products?’, ‘Please imagine that you can apply for a job at Company A. Would you feel motivated to apply for a job at Company A?’, ‘Would you feel motivated to work for Company A?’ (ɑ = 0.86).

Results

We conducted a MANOVA with communication about CSR activities of Company A (yes/no) as the between-subjects variable and dependent variables. This revealed a multivariate significant effect of the experimental manipulation F (3,93) = 2.73, p = 0.048. We then examined univariate effects on morality, competence and stakeholders’ support separately.

Morality and competence

Consistent with Hypothesis 1, participants who read that Company A was engaged in CSR activities viewed Company A as more moral (morality M csr = 4.51, SD = 0.95) than participants who didn’t read anything about CSR activities of Company A (morality M no csr = 4.00, SD = 1.17), F (1, 95) = 5.30, p = 0.024. Like in Study 1, the effect of the experimental condition on competence was not significant F (1,95) = 1.11, p = 0.30, countering the alternative explanation that information about CSR activities improves the overall impression of the company.

Stakeholders’ support

The univariate effect on stakeholders’ support was significant, F (1,95) = 5.30, p = 0.024. Consistent with Hypothesis 2, participants who had read that Company A was engaged in CSR activities expressed higher stakeholder’ support for Company A (M csr = 4.67, SD = 1.21) than participants who didn’t read about CSR activities of Company A (M no csr = 4.10, SD = 1.22).

Mediation

A mediation model analysis was conducted using PROCESS macro (Hayes, 2017) for SPSS based on 10,000 bootstrap resamples.

The model shows that communications about CSR activities indirectly influenced stakeholders’ support through its effect on the perceived morality of a company. The participants, who read about CSR activities, perceived Company A to be more moral and they also showed more support for the company. The confidence interval for the indirect effect was above 0. Thus, in line with predictions, the analysis provided support for our reasoning that morality (b = 0.28, SE = 0.13; CI = LL: 0.0.05; UL: 0.58, 10,000 bootstrap resamples), accounts for the relationship between CSR activities and stakeholders’ support. Thus, the results are consistent with Hypothesis 3, that morality mediates the relationship between CSR activities and stakeholders’ support.

Cross-country comparison: additional analysis comparing the results of Study 1 (the UK) and Study 2 (Russia)

Results

To check whether the hypothesized effects are robust across both national contexts, we additionally compared the results of the two studies.

We conducted a 2 × 2 MANOVA with a CSR experimental condition (CSR communication vs. control) and country (the UK vs. Russia) as the between-subjects variables and perceived morality, competence and stakeholders’ support as dependent variables. This revealed significant multivariate main effects of country (F (3,296) = 9.01, p < 0.001) and the CSR experimental condition (F (3,296) = 6.57, p < 0.001). There was no interaction effect (F (3,296) = 0.23, p = 0.88), indicating that our experimental manipulations had parallel effects in both countries. The fact that there is no interaction means that the theorized processes worked similarly in both countries.

At the univariate level, the effect of country was significant for morality (F (1,298) = 23.23, p < 0.001), stakeholders’ support (F (1,298) = 13.35, p < 0.001), and competence (F (1,298) = 5.32, p = 0.42). The relevant means show that participants in the UK perceived the company as more moral (M UK = 4.87, SD = 1.04, M Russia = 4.23, SD = 1.10) and more competent than in Russia (M UK = 5.30, SD = 0.96, M Russia = 5.01, SD = 0.98). UK participants also expressed more support for the company (M UK = 4.95, SD = 1.16, M Russia = 4.40, SD = 1.23) than Russian participants. This shows that, there were differences in people’s perceptions between those two countries, where UK perceptions were overall more positive that the perceptions of Russian participants.

At the univariate level, across the two national samples, the effect of CSR experimental condition was significant for morality (F (1,298) = 12.32, p = 0.001) and stakeholders’ support (F (1,298) = 9.60, p = 0.002). There was no significant univariate effect for competence (F (1,298) = 0.86, p = 0.34).

The relevant means show that in the experimental condition participants perceived the company as more moral (M csr = 4.90, SD = 0.99; M control = 4.45, SD = 1.15) than in the control condition. They also expressed more support for the company (M csr = 5.00, SD = 1.11, M control = 4.56, SD = 1.23) in the experimental condition compared to the control condition.

These results provide support to Hypotheses 1 and 2. We show that, regardless of the overall difference in evaluations between the countries, the manipulation had the same effect in both countries: there was an overall main effect of the manipulation and no interaction effect.

Mediation analysis

As a next step, we carried out a mediation analysis with total participants from both studies. The confidence interval for the indirect effect was above 0. Thus, in line with predictions, the analysis provided support for our reasoning that morality (b = 0.298, SE = 0.087; CI = LL: 0.1348; UL: 0.478, 10,000 bootstrap resamples), accounts for the relationship between CSR activities and stakeholders’ support. Thus, the results are consistent with Hypothesis 3, that morality mediates the relationship between CSR activities and stakeholders’ support.

Discussion

Theoretical contributions

Several theoretical implications follow from our work. First, building on Social Identity Theory (Tajfel, 1974; Tajfel & Turner, 1979, 1986) and theories on social evaluation of others (Abele & Wojciszke, 2007; Hack et al., 2013; Wojciszke, et al., 1998), we theorize and demonstrate in two experimental design studies that learning that a company is engaged in CSR activities leads to an increase in perceived morality of that company. The perceived organizational morality, in turn, increases stakeholders’ support. Thus, we also expand current understanding of the mechanisms which impact the relationship between CSR and stakeholders’ support (Aguinis & Glavas, 2012; Hillenbrand et al., 2013). By applying theories of social evaluation to people’s assessments of companies, we extend the emerging theory on how people develop impressions of non-human subjects (Ashforth et al., 2020; Epley et al., 2007; Gawronski et al., 2018; Mishina et al., 2012).

Second, our work extends current insights on strategic CSR and international management. We test our theorizing in two different countries: the UK and Russia. Most CSR work to date has been carried out in a single country context (Lim et al., 2018). As companies become more global, there is an increased demand for more cross-country CSR research (Scherer & Palazzo, 2011), which we address in the present research.

Furthermore, experiment based CSR research is often dominated by WEIRD samples (e.g. (De Vries et al., 2015; Ellemers et al., 2011; Chopova & Ellemers, 2023; see also Ellemers & Chopova, 2021). We, on the other hand, test our theorizing in two countries with different business practices, which can impact on development and perceptions of CSR. We find mean level differences between perceptions reported by participants in those two countries, showing that, overall, our study participants in Russia are more critical and less supportive of the company than participants in the UK. Responding to the call to devote more academic attention to CSR in developing countries (Jamali & Karam, 2018; Jamali & Mirshak, 2007), we were able to demonstrate that the impact of CSR on perceived organizational morality and stakeholders’ support remains the same across study samples obtained in the UK and Russia.

Furthermore, we address the identified need in the social psychology for testing support for general theory both in WEIRD and non-WEIRD countries, as most of the current research is carried out in WEIRD countries, while most of the world lives in non-WEIRD countries (Henrich et al., 2010a). While it is encouraging to note that some recent work has been aiming to address this issue (Pagliaro et al., 2021), those attempts remain rare. Thus, we extend current insights in social psychology on morality as a key dimension in social judgment by demonstrating that SIT (Tajfel, 1974; Tajfel & Turner, 1979, 1986) and theories on social evaluations of others (Abele & Wojciszke, 2007; Hack et al., 2013; Wojciszke et al., 1998) are also applicable in a non-WEIRD country.

Practical implications

Our work also has clear practical implications. First, experimental research is the key to understand what people can do to alter stakeholders’ responses to a company in terms of practical interventions. Thus, we provide strong evidence that communicating about CSR enhances perceived organizational morality and stakeholders’ support.

Second, there seems to be some testimony in the literature that morality is not always seen by businesses as important for CSR communications (Norberg, 2018). Our research shows that managers should not shy away from explaining that companies engage in CSR for moral or ethical reasons. These observations are also supported by a different line of work, where it was shown that the focus on the business case solely was detrimental to managers’ inclinations to engage in CSR as these managers experienced weaker moral emotions when confronted with ethical problems (Hafenbradl & Waeger, 2017). Our recommendations are also in line with the reported evolution of concept CSR in the literature and the statements that business interests can go together with sustainability efforts (Porter & Kramer, 2011; Porter & Kramer, 2018; Latapí Agudelo et al., 2019; Matten & Moon, 2020).

Finally, there seems to be a notion among some practitioners that CSR might be less important in emerging economies. For example, in 2016, the Netherlands Enterprise Agency, on a commission from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Netherlands, published a fact sheet about Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) in Russia for companies wishing to work in the Russian Federation. This stated that “there is still limited support for CSR in [Russian] society”. This sweeping statement does not specify what is meant by “society”, or how they reached this conclusion. We hope that our work can inspire practitioners working in developing countries and in Russia, in particular, to take note that while there can be differences in perceptions of CSR between countries, CSR activities and the perceived moral image of a company are important for stakeholders’ support.

Limitations

In this research, we see that Russian participants, in general, evaluate the company more negatively than UK-based participants. We have not addressed why this could be the case, which can be seen as a limitation. However, we would like to point out that this was not the focus of our research. Nevertheless, we demonstrated that shifts in perceived morality are possible due to specific communications, regardless of higher vs. lower levels of overall perceived morality. In fact, we propose that the fact this causal relationship could be demonstrated in both countries, regardless of the significant differences in the evaluations between the countries, speaks to the strength of the mechanisms we examine in our research.

Furthermore, we used an “unknown” mid-size IT consultancy company as a basis for experimental studies. It can be argued that people generally are less likely to have strong views about IT consultancy companies, which can perhaps be seen as a limitation, as people usually have views and associated with certain industries or products (e.g. banking, tobacco, Coca-Cola). To this, we would like to highlight that our aim was to show how the processes work in general. Thus, we explicitly chose to have a company that people are less likely to have preconceived views about.

Future directions

In this research, we specifically focused on a company with a relatively neutral image with respect to CSR. It is known, that some industries, such as the financial sector or tobacco, are negatively evaluated by the general public in the moral domain in particular. We know that a negative moral image is more difficult to repair, and it is particularly problematic for people working in those types of industries (Ashforth & Kreiner, 2014; Chopova & Ellemers, 2023). Moral disengagement (Bandura, 1999) can be a potential response of current investors and employees to the experience of social identity threat when the moral standing of their organization or their professional group is called into question. Future research might want to study how CSR communications affect morality and stakeholders’ support in industries with a priori negative moral image (Hadani, 2023).

We apply prior social psychological findings to non-human targets, thus building on the fact that humans can anthropomorphize non-human targets (Ashforth et al., 2020; Epley et al., 2007). In our work, we used a broad definition of CSR, including both human-focused (e.g. employees’ focused) and non-human focused (environmental protection) activities, which, we hope, improves the generalizability of our findings. We showed that this broad CSR definition leads to an increase in the perceived organizational morality. Future research might want to study to which extent the type of CSR activity impacts on the perception of organizational morality. Historically, western religious and ethical thinking was mainly human-centric, where human actions affecting non-humans were not perceived as morally relevant (Pandey et al., 2013). Hence, it is possible that people would tend to see human-focused CSR activities as more moral than environmentally focused activities. Additionally, prior work showed that people have different personal tendencies to anthropomorphize non-human targets (Waytz et al., 2010). Further research might want to examine to what extent this variable can be a moderator for the relationship between learning that a company is engaged in CSR activities, perceived organizational morality and stakeholders’ support.

Conclusion

Our paper has multiple implications for CSR and social psychological literature. Namely we demonstrate in two experimental design studies that corporate CSR communications lead to an increase in the perceived organizational morality, which in turn leads to an increase in stakeholders support. We build on social psychological literature, we explain the processes underlying this relationship. We show that morality is a relevant dimension for evaluation of companies by stakeholders, thus, extending prior findings about the importance of morality for evaluations of human targets to non-human targets. We empirically test our theory in both WEIRD (the UK) and in non-WEIRD (Russia) country. We believe that our findings are particularly relevant in the current context where various politicians and media suggest that psychological differences are too large to be able to compare people from a country such as the UK and to people from Russia. While we only focus on CSR perceptions and subsequent stakeholders’ support, our work suggests that in that area the underlying psychological mechanisms work in a similar fashion in both countries.

Availability of data and materials

The data is available at the university depository (public access can be requested).

Abbreviations

- M:

-

Mean

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- LL:

-

Lower limit

- UL:

-

Upper limit

References

Abele, A. E., Ellemers, N., Fiske, S. T., Koch, A., & Yzerbyt, V. (2021). Navigating the social world: Toward an integrated framework for evaluating self, individuals, and groups. Psychological Review, 128(2), 290.

Abele, A. E., & Wojciszke, B. (2007). Agency and Communion From the Perspective of Self Versus Others. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 93(5), 751–763. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.93.5.751

Aguinis, H., & Glavas, A. (2012). What We Know and Don’t Know About Corporate Social Responsibility: A Review and Research Agenda. Journal of Management, 38(4), 932–968. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206311436079

Aguinis, H., & Glavas, A. (2019). On Corporate Social Responsibility, Sensemaking, and the Search for Meaningfulness Through Work. Journal of Management, 45(3), 1057–1086. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206317691575

Alon, I., Lattemann, C., Fetscherin, M., & li, S., & Schneider, A. M. (2010). Usage of public corporate communications of social responsibility in Brazil, Russia, India and China (BRIC). International Journal of Emerging Markets, 5(1), 6–22. https://doi.org/10.1108/17468801011018248

Aluchna, M., Idowu, S.O., Tkachenko, I. (2020). Exploring the Issue of Corporate Governance in Central Europe and Russia: An Introduction. In: Aluchna, M., Idowu, S.O., Tkachenko, I. (eds) Corporate Governance in Central Europe and Russia. CSR, Sustainability, Ethics & Governance. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-39504-9_1

Ashforth, B. . E., & Mael, F. (1989). Social Identity Theory and the Organization. Academy of Management Review, 14(1), 20–39.

Ashforth, B. E., Schinoff, B. S., & Brickson, S. L. (2020). My company is friendly”, “mine’s a rebel”: Anthropomorphism and shifting organizational identity from “what” to “who. Academy of Management Review, 45(1), 29–57. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2016.0496

Ashforth, B. E., & Kreiner, G. E. (2014). Dirty Work a n d Dirtier Work: Differences in Countering Physical, Social, a n d M o r a l Stigma. Management and Organization Review, 10(1), 81–108. https://doi.org/10.1111/morc.l2044

Awuah, L. S., Amoako, K. O., Yeboah, S., Marfo, E. O., & Ansu-Mensah, P. (2021). Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR): Motivations and challenges of a Multinational Enterprise (MNE) subsidiary’s engagement with host communities in Ghana. International Journal of Corporate Social Responsibility, 6(1), 1–13.

Bandura, A. (1999). Moral disengagement in the perpetration of inhumanities. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 3(3), 193–209.

Barkemeyer, R., Preuss, L., & Ohana, M. (2018). Developing country firms and the challenge of corruption: Do company commitments mirror the quality of national-level institutions? Journal of Business Research, 90(April), 26–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.04.025

Baskentli, S., Sen, S., Du, S., & Bhattacharya, C. . B. (2019). Consumer reactions to corporate social responsibility : The role of CSR domains. Journal of Business Research, 95, 502–513. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.07.046

Bauman, C. W., & Skitka, L. J. (2012). Corporate social responsibility as a source of employee satisfaction. Research in Organizational Behavior, 32, 63–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.riob.2012.11.002

Boubakri, N., El Ghoul, S., Guedhami, O., & Wang, H. H. (2021). Corporate social responsibility in emerging market economies: Determinants, consequences, and future research directions. Emerging Markets Review, 46, 100758.

Carroll, A. B. (2016). Carroll’s pyramid of CSR: Taking another look. International Journal of Corporate Social Responsibility, 1(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40991-016-0004-6

Cheon, B. K., Melani, I., & Hong, Y. Y. (2020). How USA-Centric Is Psychology? An Archival Study of Implicit Assumptions of Generalizability of Findings to Human Nature Based on Origins of Study Samples. Social Psychological and Personality Science. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550620927269

Chopova, T., & Ellemers, N. (2023). The importance of morality for collective self-esteem and motivation to engage in socially responsible behavior at work among professionals in the finance industry. Business Ethics, the Environment & Responsibility., 32(1), 401–414.

Cuddy, A. . J. . C., Fiske, S. . T., Kwan, V. . S. . Y., Glick, P., Demoulin, S., Leyens, J. .-P., & Ziegler, R. (2009). Stereotype content model across cultures: towards universal similarities and some differences. The British Journal of Social Psychology / the British Psychological Society, 48(Pt 1), 1–33. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466608X314935

Cuddy, A. J. C., Fiske, S. T., & Glick, P. (2007). The BIAS map: Behaviors from intergroup affect and stereotypes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92(4), 631–648. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.92.4.631

De Vries, G., Terwel, B. W., Ellemers, N., & Daamen, D. D. L. (2015). Sustainability or profitability? How communicated motives for environmental policy affect public perceptions of corporate greenwashing. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 22(3), 142–154. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.1327

Ellemers, N., Kingma, L., van de Burgt, J., & Barreto, M. (2011). Corporate Social Responsibility as a Source of Organizational Morality, Employee Commitment and Statisfaction. Journal of Organisational Moral Psychology, 1(2), 97–124.

Epley, N., Waytz, A., & Cacioppo, J. . T. (2007). n Seeing Human : A Three-Factor Theory of Anthropomorphism. Psychological Review, 114(4), 864–886. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.114.4.864

Ellemers, N., & Chopova, T. (2021). The social responsibility of organizations: Perceptions of organizational morality as a key mechanism explaining the relation between CSR activities and stakeholder support. Research in Organizational Behavior, 41, 100156.

Ellemers, N., De Gilder, D., & Haslam, S. A. (2004). Motivating individuals and groups at work: A social identity perspective on leadership and group performance. Academy of Management Review, 29(3), 459–478. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMR.2004.13670967

Ervits, I. (2021). CSR reporting by Chinese and Western MNEs: Patterns combining formal homogenization and substantive differences. International Journal of Corporate Social Responsibility, 6(1), 1–24.

Farooq, O., Payaud, M., Merunka, D., & Valette-Florence, P. (2014). The Impact of Corporate Social Responsibility on Organizational Commitment: Exploring Multiple Mediation Mechanisms. Journal of Business Ethics, 125(4), 563–580. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-013-1928-3

Fennis, B. M., & Pruyn, A. T. H. (2007). You are what you wear: Brand personality influences on consumer impression formation. Journal of Business Research, 60(6), 634–639. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2006.06.013

Fifka, M. S., & Pobizhan, M. (2014). An institutional approach to corporate social responsibility in Russia. Journal of Cleaner Production, 82, 192–201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2014.06.091

Fiske, S. T., Cuddy, A. J. C., & Glick, P. (2007). Universal dimensions of social cognition: Warmth and competence. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 11(2), 77–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2006.11.005

Fiske, S. T., Cuddy, A. J. C., Glick, P., & Xu, J. (2002). A model of (often mixed) stereotype content: Competence and warmth respectively follow from perceived status and competition. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82(6), 878–902. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.82.6.878

Gawronski, B., Rydell, R. J., Houwer, J. De, Brannon, S. M., Ye, Y., Vervliet, B., & Hu, X. (2018). Contextualized Attitude Change. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology (1st ed., Vol. 57). Elsevier Inc. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.aesp.2017.06.001

Goodwin, G. P., Piazza, J., & Rozin, P. (2014). Moral character predominates in person perception and evaluation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 106(1), 148–168. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0034726

Grabner-Kräuter, S., Breitenecker, R. J., & Tafolli, F. (2020). Exploring the relationship between employees’ CSR perceptions and intention to emigrate: Evidence from a developing country. Business Ethics, the Environment & Responsibility, 30, 87–102.

Hack, T., Goodwin, S. A., & Fiske, S. T. (2013). Warmth Trumps Competence in Evaluations of Both Ingroup and Outgroup. International Journal of Science, Commerce and Humanities, 1(6), 99–105. https://doi.org/10.1530/ERC-14-0411.Persistent

Hadani, M. (2023). The impact of trustworthiness on the association of corporate social responsibility and irresponsibility on legitimacy. Journal of Management Studies, 61(4), 1266-1294.

Hafenbradl, S., & Waeger, D. (2017). Indeology and the Micro-Foundations of CSR: Why Executives Believe in the Business Case for CSR and How This Affects Their CSR Engagements. Academy of Management Jou, 60(4), 1582–1606. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2014.0691

Haslam, S. A., Jetten, J., Postmes, T., & Haslam, C. (2009). Social identity, health and well-being: An emerging agenda for applied psychology. Applied Psychology, 58(1), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-0597.2008.00379.x

Haslam, S. A., Powell, C., & Turner, J. C. (2000). Social identity, self-categorization, and work motivation: Rethinking the contribution of the group to positive and sustainable organisational outcomes. Applied Psychology, 49(3), 319–339. https://doi.org/10.1111/1464-0597.00018

Hayes, A. . F. . (2017). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford publications.

Henrich, J., Heine, S. . J., & Norenzayan, A. (2010a). Most people are not WEIRD. Nature, 466(7302), 29–29. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X0999152X

Henrich, J., Heine, S. J., & Norenzayan, A. (2010b). The weirdest people in the world? Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 33(2–3), 61–83. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X0999152X

Hillenbrand, C., Money, K., & Ghobadian, A. (2013). Unpacking the Mechanism by which Corporate Responsibility Impacts Stakeholder Relationships. British Journal of Management, 24(1), 127–146. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8551.2011.00794.x

Holland, P. W. (1986). Statistics and causal inference. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 81(396), 945–960. https://doi.org/10.1080/01621459.1986.10478354

Idemudia, U. (2011). Corporate social responsibility and developing countries: Moving the critical CSR research agenda in Africa forward. Progress in Development Studies, 11(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1177/146499341001100101

Jamali, D., & Karam, C. (2018). Corporate Social Responsibility in Developing Countries as an Emerging Field of Study. International Journal of Management Reviews, 20(1), 32–61. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijmr.12112

Jamali, D., & Mirshak, R. (2007). Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR): Theory and practice in a developing country context. Journal of Business Ethics, 72(3), 243–262. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-006-9168-4

Kervyn, N., Fiske, S., & Malone, C. (2012). NIH Public Access. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 22(2). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcps.2011.09.006.Brands

Khojastehpour, M., & Jamali, D. (2021). Institutional complexity of host country and corporate social responsibility: Developing vs developed countries. Social Responsibility Journal, 17(5), 593–612.

Koleva, P., Rodet-Kroichvili, N., David, P., & Marasova, J. (2010). Is corporate social responsibility the privilege of developed market economies? some evidence from central and eastern europe. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 21(2), 274–293. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585190903509597

Kolk, A., & van Tulder, R. (2010). International business, corporate social responsibility and sustainable development. International Business Review, 19(2), 119–125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2009.12.003

König, C. . J., Langer, M., Fell, C. . B., Pathak, R. . D., Bajwa, N., ul, H., Derous, E., & Ziem, M. (2020). Economic Predictors of Differences in Interview Faking Between Countries: Economic Inequality Matters, Not the State of Economy. Applied Psychology, 70(3), 1360–1379. https://doi.org/10.1111/apps.12278

Kuznetsov, A., Kuznetsova, O. ., & Warren, R. (2009). CSR and the legitimacy of business in transition economies: The case of Russia. Scandinavian Journal of Management, 25(1), 37–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scaman.2008.11.008

Latapí Agudelo, M. A., Jóhannsdóttir, L., & Davídsdóttir, B. (2019). A literature review of the history and evolution of corporate social responsibility. International Journal of Corporate Social Responsibility, 4(1), 1–23.

Leach, C. . W., Ellemers, N., & Barreto, M. (2007). Group virtue: The importance of morality (vs. competence and sociability) in the positive evaluation of in-groups. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 93(2), 234–249. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781107415324.004

Leach, C. W., Bilali, R., & Pagliaro, S. (2015). Groups and Morality. APA Handbook of Personality and Social Psychology, 2, 123–149.

Lim, R. E., Sung, Y. H., & Lee, W. N. (2018). Connecting with global consumers through corporate social responsibility initiatives: A cross-cultural investigation of congruence effects of attribution and communication styles. Journal of Business Research, 88(February), 11–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.03.002

MacInnis, D. J., & Folkes, V. S. (2017). Humanizing brands: When brands seem to be like me, part of me, and in a relationship with me. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 27(3), 355–374. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcps.2016.12.003

Matten, D., & Moon, J. (2020). Reflections on the 2018 decade award: The meaning and dynamics of corporate social responsibility. Academy of Management Review, 45(1), 7–28.

McWilliams, A., & Siegel, D. (2001). Profit maximizing corporate social responsibility. Academy of Management Review, 26(4), 504-505.

Mishina, Y., Block, E. . S., & Mannor, M. (2012). he Path Dependence of Organizational Reputation: How Social Judgement Influences Asessements of Capability and Charecter. Strategic Management Journal, 477, 459–477. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj

Mitnick, B. M., Windsor, D., & Wood, D. J. (2023). Moral CSR. Business & Society, 62(1), 192–220.

Moon, J., & Shen, X. (2010). CSR in China research: Salience, focus and nature. Journal of Business Ethics, 94(4), 613–629. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-009-0341-4

Norberg, P. (2018). Bankers Bashing Back : Amoral CSR Justifications. Journal of Business Ethics, 147, 401–418. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-015-2965-x

Pagliaro, S., Sacchi, S., Pacilli, M. G., Brambilla, M., Lionetti, F., Bettache, K., ... & Zubieta, E. (2021). Trust predicts COVID-19 prescribed and discretionary behavioral intentions in 23 countries. PloS one, 16(3), e0248334.

Pandey, N., Rupp, D. .E., & Thornton, M. (2013). The morality of corporate environment sustainability: A psychological and philosophical perspective. In A. H. Huffman S. R. Klein (Eds.). Green Organizations: Driving Change with I-O. New York: NY: Routledge. Psychology.

Porter, M. . E., & Kramer, M. . R. (2011). Creating shared value. Harvard Business Review. January-February.

Porter, M. E., & Kramer, M. R. (2018). Creating shared value: How to reinvent capitalism—And unleash a wave of innovation and growth. Managing sustainable business: An executive education case and textbook (pp. 323–346). Springer, Netherlands.

Preuss, L., & Barkemeyer, R. (2011). CSR priorities of emerging economy firms: Is Russia a different shape of BRIC? Corporate Governance, 11(4), 371–385. https://doi.org/10.1108/14720701111159226

Raithel, S., & Schwaiger, M. (2015). The effects of corporate reputation perceptions of the general public on shareholder value. Strategic Management Journal, 36(6), 945–956.

Sabherwal, A., Ballew, M. T., van Der Linden, S., Gustafson, A., Goldberg, M. H., Maibach, E. W., ... & Leiserowitz, A. (2021). The Greta Thunberg Effect: Familiarity with Greta Thunberg predicts intentions to engage in climate activism in the United States. Journal of Applied Social Psychology.

Scherer, A. . G., & Palazzo, G. (2011). The New Political Role of Business in a Globalized World: A Review of a New Perspective on CSR and its Implications for the Firm, Governance, and Democracy. Journal of Management Studies, 48, 4. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2010.00950.x

Shadish, W. . R., Cook, T. . D., & Campbell, D. . T. (2002). Experimental and quasi-experimental designs for generalized causal inference/William R. Shedish, Thomas D. Cook, Donald T. Campbell. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Shea, C. T., & Hawn, O. (2019). Microfoundations of Corporate Social Responsibility and Irresponsibility. Academy of Management Journal, 62(5), 1609–1642.

Simpson, S. N. Y., & Aprim, E. K. (2018). Do corporate social responsibility practices of firms attract prospective employees? Perception of university students from a developing country. International Journal of Corporate Social Responsibility, 3(1), 1–11.

Stokburger-Sauer, N., Ratneshwar, S., & Sen, S. (2012). Drivers of consumer-brand identification. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 29(4), 406–418. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijresmar.2012.06.001

Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. C. (1979). An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. In W. G. Austin & S. Worchel (Eds.), The social psychology of intergroup relations (pp. 33–47). Monterey, CA: Brooks/Cole.

Tajfel, H. (1974). Social Identity and Intergroup Behaviour. Information (international Social Science Council), 13(2), 65–93.

Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. C. (1986). The Social Identity Theory of Intergroup Behavior. In S. Worchel & W. G. Austin (Eds.), Psychology of Intergroup Relation (pp. 7–24). Hall Publishers.

Tkachenko, I., & Pervukhina, I. (2020). Stakeholder value assessment: Attaining company-stakeholder relationship synergy. Corporate Governance in Central Europe and Russia: Framework, Dynamics, and Case Studies from Practice, 89–105.

Tuškej, U., Golob, U., & Podnar, K. (2013). The role of consumer-brand identification in building brand relationships. Journal of Business Research, 66(1), 53–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2011.07.022

van Prooijen, A.-M., & Ellemers, N. (2015). Does it pay to be moral? How indicators of morality and competence enhance organizational and work team attractiveness. British Journal of Management, 26(2), 225–236. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8551.12055

van Prooijen, A.-M., Ellemers, N., Van der Lee, R., & Scheepers, D. (2018). What seems attractive may not always work well : Evaluative and cardiovascular responses to morality and competence levels in decision-making teams. Group Processes and Intergroup Relations. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430216653814

Wang, X., Li, F., & Sun, Q. (2018). Confucian ethics, moral foundations, and shareholder value perspectives: An exploratory study. Business Ethics, 27(3), 260–271. https://doi.org/10.1111/beer.12186

Waytz, A., Cacioppo, J., & Epley, N. (2010). Who sees human? The stability and importance of individual differences in anthropomorphism. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 5(3), 219–232.

Wojciszke, B. (1994). Multiple meanings - competence morality. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 67(2), 222–232.

Wojciszke, B., Bazinska, R., & Jaworski, M. (1998). On the Dominance of Moral Categories in Impression Formation. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. https://doi.org/10.1177/01461672982412001

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

NWO Spinoza grant to Naomi Ellemers.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Authors contributed equally to the paper. Dr Chopova is corresponding author.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The research has been approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Utrecht. The research complies with institutional standards on research involving Human Participants and Informed Consent.

We have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Competing interests

None.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Company A is engaged in Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) activities. Its CSR activities are focused on the role the company plays in the community where it operates, on the company’s impact on the environment and on creating a diverse workforce. Please see below the extract from the latest press release about Company A’s Corporate Social Responsibility activities (Fig.

2).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chopova, T., Ellemers, N. & Sinelnikova, E. Morality matters: social psychological perspectives on how and why CSR activities and communications affect stakeholders’ support - experimental design evidence for the mediating role of perceived organizational morality comparing WEIRD (UK) and non-WEIRD (Russia) country. Int J Corporate Soc Responsibility 9, 10 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40991-024-00088-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40991-024-00088-w