Abstract

Background

Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) has experienced an unprecedented mining boom since the mid-2000s with unknown effects on sexual and reproductive health (SRH). This study takes the essential first steps of summarizing the available literature regarding SRH in mining contexts in LAC, identifying critical gaps in knowledge, and discussing main implications for future research.

Methods

We conducted a scoping review with a systematic search of health literature in four databases, reference lists of selected papers, and citations in Google Scholar.

Results

The systematic search yielded 592 primary references and 16 articles from LAC. The 11 papers finally selected were conducted in gold-mining contexts in Brazil, Venezuela, Guyana, Peru, and Colombia, between 1995 and 2016. Ten studies centered on measuring HIV/STD prevalence among mineworkers and other populations; few examined associated risk factors. Eight studies reported high HIV/STD prevalence in the study population. None of the studies explored broader SRH issues.

Conclusions

Available research is scarce and provides limited evidence on SRH in LAC mining contexts. Critical gaps include little knowledge on (1) broader SRH impacts besides HIV/STDs, (2) SRH in settings different from gold-mining contexts in Amazon countries, (3) mechanisms shaping SRH in LAC mining contexts, and (4) effective interventions in these scenarios. Future research must consider the distinctive demographic, environmental, socioeconomic, and gender dynamics triggered by the mining economy in the analysis of the relationship between mining and SRH, particularly in a period of extractive boom.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Consistent evidence characterizes mining as one of the world’s most hazardous activities because of the high risk of occupational accidents and toxicological exposure among mineworkers and communities [1]. Conversely, the current knowledge about the relationship between mining and sexual and reproductive health (SRH) is limited. The existing literature has been almost solely concerned with the spread of HIV, mostly in sub-Saharan Africa, where studies have observed that mining communities had a higher prevalence of HIV and other sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) than the general population [2, 3]. Some investigations found associations between having HIV/STDs and individual risk factors in mining contexts; these factors include single status, alcohol and drug use, history of previous STDs, partnership or sex with a mineworker, multiple sexual partners, paying for sex, transactional sex, and non-use of condoms [4,5,6,7,8]. While these studies focused mainly on groups considered at high-risk (typically mineworkers and sex workers), high prevalence of HIV/STDs and associations with similar risk factors have been described among other population groups in mining communities [4, 7, 9]. In general, this literature recognizes a relationship between the mining context and the dynamics of the HIV/STDs spread. Labor migration—linked to single-sex lodging and isolation and separation of miners from families—has been strongly associated with HIV transmission [2, 9,10,11]. Besides the spread of HIV/STDs, only a handful of studies have explored broader impacts of mining on SRH such as early marriage, increased fertility, short birth intervals, and lack of reproductive decision-making among local women [12,13,14].

Mining boom in Latin America and the Caribbean

The study of the relationship between mining and SRH in Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) is pertinent, as the region has experienced an unprecedented mining boom since the mid-2000s. The increased global demand for and rising prices of minerals [15], along with national mining laws favoring foreign investment [16], fueled the recent mining boom in the region. Between 2005 and 2010, the prices of coal, nickel, and copper doubled, and the price of gold increased five times between 2002 and 2011 [17]. In the same period, LAC received 24% of the global mining exploration budget, the largest investment for a single region [18]. As a result, mining production increased significantly, leading to a reactivation and intensification of operations in towns with established mining activities and, more significantly, the arrival of new mining endeavors in non-mining areas. Despite 50 to 70% of the regional mining production coming from industrial mining, most of the mining operations corresponded to artisanal and small-scale mining (ASM), which employed the majority of the region’s mining workforce [19]. In particular, illegal gold mining, predominantly of small scale, was estimated to employ directly around 350,000 people in Amazon countries and sustain about 500,000 people only in Bolivia and Peru [20].

Despite the high dividends from the mining sector commonly reported in the region (benefits for national economies remain debatable) [15, 21, 22], the mining boom has been associated with environmental, social, and health impacts at the local level, particularly affecting vulnerable populations. Studies and reports examining the impacts of mining in LAC have described environmental crises [20, 23, 24]; social conflicts and mobilization against extractive operations [25]; human rights violations to indigenous and Afro-descendant groups across the region [26]; child labor, sexual violence, sexual exploitation, and human trafficking linked to illegal gold mining in the Amazon [27, 28]; and environmental health effects, mental health impacts, and increased risks of infectious diseases, including STDs [29].

Sexual and reproductive health in Latin America and the Caribbean

The mining boom in LAC takes place in a scenario of pending challenges in SRH. Estimations of either intimate partner violence or non-partner sexual violence against women vary between 24% in the Southern LAC and 41% in the Andean LAC—higher than the global estimation of 35% [30]. The region has the second highest rate of adolescent childbearing worldwide, 73 births per 1000 women aged 15–19 [31], and the highest estimated incidence of abortion and unsafe abortion, 44 and 31 abortions per 1000 women aged 15–44, respectively [32]. Most importantly, regional figures hide profound disparities in SRH between social groups. Lack of access to contraception, reproductive health services or maternal care, maternal mortality and morbidity, and sexual violence are higher among rural, low-income, low-educated, and ethnic minority women, principally indigenous and Afro-descendants, than the general population [31].

The recent mining boom in the region, in a scenario of profound SRH inequities, provides a strong rationale for examining to what extent the mining dynamics have impacted SRH at the local level. To this end, it is necessary to establish first what is currently known about the relationship between mining and SRH in the region. This scoping literature review takes the essential first steps of examining and summarizing the available literature regarding SRH in LAC mining contexts, identifying critical gaps in knowledge, and discussing primary implications for future research.

Methods

A scoping review is a systematic process intended to explore the extent and nature of research on a particular topic, identify gaps in knowledge, and summarize and disseminate findings [33]. One of the key purposes of a scoping review is to provide an evidence background to guide future research, practice, and decision-making on the subject of interest [34]. A scoping review is particularly relevant when there is not a clear picture of the existing evidence regarding a field of research. That is, scoping reviews are useful to address emergent or unexplored topics.

We conducted a scoping review with a systematic search of health literature during May 2017, in PubMed and PaHO-VHL (Pan American Health Association-Virtual Health Library), and two LAC databases, LILACS (Latin American and Caribbean Health Sciences) and SciELO (Scientific Electronic Library Online). We scanned reference lists and citations of the selected papers in Google Scholar to identify additional studies.

For the search strategy, we used combinations of two groups of terms in English and Spanish (only English in PubMed). First, “mining” and “mining industry.” Second, “sexual health,” “reproductive health,” “maternal health,” “HIV,” “sexually transmitted diseases,” “sexually transmitted infections,” “fertility,” and “sexual behavior.” To narrow the search in PubMed and PaHO-VHL, we used the term of exclusion “data mining.”

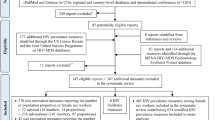

We included only references placed in LAC countries, with no limitation by the date of publication. We excluded articles addressing exclusively environmental and occupational health (e.g., exposure to pollutants, even regarding reproductive health outcomes), health issues different from SRH (e.g., children’s health), and non-health issues. We excluded non-primary research papers (e.g., reports, editorial comments, and letters to the editor). The selection process included the elimination of duplicates, selection of references based on titles and abstracts, identification of full-text papers, selection of additional studies from reference lists and citations in Google Scholar, and final selection of full-text primary research articles (Fig. 1).

Finally, we summarized and discussed the selected articles based on the country and sub-region of the study, key features of the mining operations (minerals, scale, and formality/legality), the purpose of the study, population and sample size, and main findings on SRH.

Results

The scoping review yielded 592 primary references and retrieved 16 articles placed in LAC countries that focused on SRH (Fig. 1). We eliminated one article without full text and four non-primary papers, which included two recent reviews on health impact assessment related to extractive industries and hydroelectric projects in the region [29, 35]. We finally selected 11 primary research articles for analysis. Table 1 shows the main findings of the scoping review.

General characteristics of the studies: places, times, and populations

The 11 studies reviewed, conducted between 1995 and 2016 [36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46], were set in gold-mining contexts in South American countries, nine in Amazon areas. One study was set in a period previous to a mining exploitation phase [37] and one in a period of mining decline [39]. The other nine were set in periods of full mining operations. Except for the study by Orellana et al. [40], the investigations used quantitative methods and cross-sectional designs, collecting data through surveys and biological samples for HIV and STDs tests. None of the studies used a longitudinal approach to incorporate temporality in the analyses. However, the study by Astete et al. [37] considered temporality and provided a baseline in a pre-exploitation period to evaluate the health impacts of mining during the subsequent phases. Three studies sampled mostly or exclusively male miners [41, 43, 44], one included only women [39] and one focused on indigenous population [40]. The rest of the studies were sampled from the general population.

Purposes and main SRH findings of the studies

The 11 studies centered on HIV/STDs as the only SRH concern. The ten quantitative studies focused on measuring the prevalence of HIV and STDs. The study by Castro-Arroyave et al. [46] showed a low prevalence of HIV but a high prevalence of syphilis in a period of mining exploitation; the HIV prevalence contrasts with the high prevalence of HIV found by the rest of the quantitative studies in a similar stage of mining production. Astete et al. [37] described a low prevalence of HIV/STDs in a stage of pre-exploitation. Some studies identified a high prevalence of HIV/STDs among mineworkers [42], sex workers [38, 42], and health care workers [38] than the general population. Three investigations evidenced significant associations between HIV/STDs and individual risk factors such as having lived in a gold-miners camp [45], having history of STDs [43, 44], and not having used a condom with last casual sex partner [43]. Most of the quantitative studies suggested labor migration and mobility as major factors involved in HIV/STD transmission in mining places. Nevertheless, only Souto et al. [45] provided actual evidence on the association between STDs and mobility.

Two studies developed HIV prevention interventions [38, 46]. They used behavioral change approaches aimed to increase knowledge, change attitudes, and reduce stigma about HIV/STDs. Castro-Arroyave et al. [46] found change in perceptions and increases in knowledge among community leaders and other community members who participated in the program.

The study by Orellana et al. [40] provided unique insights into the links between mining and SRH. Qualitative in-depth data enabled the researchers to identify and discuss emerging themes such as population mobility and mixing, sociocultural factors (early sexual initiation, sexual identity, and gender roles), and interpersonal and behavioral factors (forced sex, unprotected sex, and transactional sex among poor women and young indigenous men). Authors concluded that “poverty, cultural beliefs related to health and sexual behaviors, gender inequality, lack of educational and employment opportunities, resource-extraction activities, and population mobility and mixing” interact and shape risk environments for the HIV/STD spread among indigenous communities ([40]: p. 1246).

Discussion

The literature reviewed about SRH in LAC mining contexts is scarce and provides limited evidence in this area of research in the region. The increased prevalence of HIV/STDs among mineworkers, sex workers, or other population groups that most of the studies showed, along with the reported associations with individual risk factors, match findings from other regions [2, 3]. The low prevalence of HIV/STDs that Castro-Arroyave et al. [46] found in a gold-mining community in Colombia, however, contrasts with the global findings. Two studies provided evidence on the role of labor migration and mobility on the spread of HIV/STDs in LAC mining contexts [40, 45]. Although they are limited, similar findings have been reported globally [2, 9,10,11].

Based on the findings of this scoping review, we identify four critical gaps in the current knowledge on SRH in LAC mining contexts. First, there is no empirical research that examines SRH broadly beyond the spread of HIV/STDs. No studies have explored SRH issues related to sexual violence against women, adolescents, and children; intimate partner violence; reproductive decision-making; use of contraception; early marriage; teenage pregnancy; abortion; maternal health; or access and use of SRH services. As discussed by Vargas-Riaño et al. in regard to maternal health research in the region [47], the dominant focus on HIV issues seems to respond primarily to research funding interests and not to the health needs of the LAC population. This gap in knowledge is also characteristic of the global research on this matter. Second, there is no empirical research regarding SRH issues in settings different from gold-mining contexts and from Mexico and Central America, the Southern LAC, and the Caribbean. The lack of studies in these other contexts is salient since numerous communities throughout Latin America have experienced the extractive boom [15, 29] with unknown effects on their SRH. Third, there is no empirical research that explores the mechanisms or pathways through which SRH is shaped in LAC mining contexts, particularly in periods of extractive boom. Finally, there is a dearth of investigations about effective SRH interventions in LAC mining contexts. In light of these needs, we discuss two key areas to consider in future research: the mining context and the production of risk in these scenarios.

The mining context revisited

The study of the relationship between mining and SRH in LAC has overlooked the context where mining takes place. For most of the studies reviewed, the construct mining referred either to the setting that delimits the location of research (the mining community, the mining camp) or an individual sociodemographic variable (the mineworker occupation). Astete et al. [37] and Miranda et al. [39] also considered the stage of mining production in their research approach, suggesting differential effects of the time of mining on SRH. Nevertheless, only Orellana et al. [40] explored and reflected on mining and other resource-extraction activities as contextual factors that interact with others to determine a “risk environment” for the spread of HIV/STDs.

The mining context in a period of extractive boom has been commonly characterized by disruptive demographic, environmental, socioeconomic, and gender dynamics triggered by the mining economy. Significant workforce migration to mining places (predominantly male) and high mining wages in mining communities relate to increases in the local demand and prices of land, housing, basic goods, and services, as described in countries like Peru [48]. The increased cost of living and high expectations of short-term returns from the mining economy pull people from rural settings to engage in mining activities and displace traditional livelihoods [49, 50]. Living conditions of migrant workers in camps and mining towns—including single-sex accommodation, isolation, and separation from families—along with large amounts of disposable cash among men have been associated with high demand for alcohol, drugs, and sex services [5, 51]. These factors have in turn been linked to an increase in the number of bars, nightclubs, and brothels [40, 52], as well as rising levels of crime and violence, particularly sexual violence, as observed in gold camps in Surinam [28] and Peru [53].

These dynamics determine a context of unbalanced gendered power relations, where women are disproportionally vulnerable to the environmental, socioeconomic, and health impacts of mining [52]. As reviewed by Jenkins [52], the mining sector often establishes a displacement from subsistence economies towards cash economies controlled by men. Women shift away from their traditional roles to become mineworkers (mainly restricted to processing tasks) or providers of services—including sex. Female mineworkers are paid less than males, even when they are performing heavy tasks like those performed by men [27, 54]. Extreme poverty may lead young girls to get involved in prostitution, bonded labor, and sexual exploitation in places of ASM and informal mining, as described in Amazon countries [27, 28]. Some studies in mining settings worldwide observed that women might engage in transactional sex as a supplementary source of income, basic goods, or favors [4, 8]. Orellana et al. [40] reported transactional sex practices among poor women and indigenous teenage boys in the Peruvian Amazon. In general, women have little access to the economic benefits of mining and become highly dependent on men, resulting in a degradation of their social status and a reinforcement of male privileges [52].

The production of SRH risk in mining contexts

The simultaneous dynamics often described in mining contexts challenge the way we address the links between mining and SRH in research and intervention. Some studies in South African mining settings showed that prevention interventions typically based on biomedical and behavioral approaches had little impact in reducing or even controlling the spread of HIV [1, 4, 8, 55]. Based on these findings, Desmond et al. [8] argued that conventional approaches—restricted to the individual level of analysis—do not represent adequately the complexity of the social and sexual networks that take place in mining contexts. Instead, Desmond et al. [8] proposed the use of a high-risk environment approach which enables structural-level analyses and interventions. The study by Orellana et al. [40] coincides with this perspective as it focused on the structural and contextual production of risk. The authors examined ecosocial levels of influence and discussed the risk environment as an appropriate category of analysis about the spread of HIV/STDs among indigenous communities. Even though the authors did not explore broad aspects of the SRH—likely occurring in these same risk environments, this approach serves as a point of reference for further exploration about the way SRH is shaped in LAC mining contexts.

Implications for future research

To address the gaps in knowledge identified, new research efforts must consider key conceptual and methodological challenges. First, they require comprehensive approaches for SRH that include, in addition to the study of HIV and STDs, broader SRH aspects related to sexual violence against women, adolescents and children, intimate partner violence, reproductive decision-making, use of contraception, early marriage, adolescent pregnancy, abortion, maternal health, and access and use of SRH services. Second, future studies must consider the mining context as a critical component of analysis, by examining the demographic, environmental, socioeconomic, and gender dynamics triggered by the mining economy, involved in the production of SRH risk. This also requires taking into account the particularities of the mining operations, i.e., minerals of extraction, stages of mining, scales, and status of formality/legality. Empirical research should consider the use of categories like risk environment instead of high-risk population, as proposed by Desmond et al. [8] and Orellana et al. [40]; the use of qualitative methods and longitudinal designs for quantitative studies; and the use of multilevel approaches to examine structural, contextual, interpersonal, and individual factors and pathways of influence involved. Finally, future research requires integrating a gender perspective for the examination of the gender roles and gender relations in mining contexts. A gender approach would facilitate the exploration and understanding of phenomena such as the unbalanced gendered power relations as determinants of SRH.

Limitations

We conducted a scoping literature review looking for peer-reviewed publications. We did not examine gray literature, e.g., dissertations, technical reports, or conference papers. Despite potential drawbacks on availability and quality, gray literature might provide insights on how other researchers and stakeholders (international, government, industry, and civil organizations) have approached the relationship between mining and SRH in LAC. For instance, Organización Internacional del Trabajo, Gobierno de Chile, and SEREMI Tarapacá [56] presented a survey on knowledge, perceptions of risk, attitudes, and practices regarding HIV among mobile mineworkers (n = 300), in the copper region of Tarapacá, Chile. Mineworkers showed high levels of knowledge in HIV issues, high demand for commercial sex (during life, 33.1%; during the past year, 13.4%), and little access to condoms (81.4% referred non-availability of condoms in the mining place). These findings, similar to those from Seguy et al. [43], also targeting male mineworkers, provide a background for further research on SRH in mining communities in Chile. At the same time, these results confirm the gaps in knowledge in the LAC region regarding the restricted interest on HIV and individual risk factors associated, as well as the lack of attention to the demographic, environmental, socioeconomic, and gender dynamics linked to the mining economy as key factors determining SRH.

Conclusions

This scoping review clarifies the current knowledge about SRH in LAC mining contexts and joins the recent reviews by Drewry, Shandro, and Winkler [29] and Pereira et al. [35] towards the understanding and assessment of the health impacts of the extractive industries in the region. We found that available research is scarce and provides limited evidence on SRH in LAC mining contexts. This is significant considering the numerous communities along LAC that have experienced a mining boom during the past decade, with unknown effects on their SRH. The critical gaps identified include little knowledge on (1) broader SRH impacts besides HIV/STDs, (2) SRH in settings different from gold-mining contexts in Amazon countries, (3) mechanisms shaping SRH in LAC mining contexts, and (4) effective interventions in these scenarios. We expect these findings stimulate LAC research teams, stakeholders, and communities interested in sexual and reproductive health and rights, gender equity, environmental justice, occupational health, and community health to advocate for and conduct new investigations on this critical but neglected topic of public health research.

References

Stephens C, Ahern M. Worker and community health impacts related to mining operations internationally. A rapid review of the literature. In: Mining and minerals for sustainable development project, vol. 25. London: International Institute for Environment and Development; 2001.

Carney JG, Gushulak BD. A review of research on health outcomes for workers, home and host communities of population mobility associated with extractive industries. J Immigr Minor Health. 2016;18(3):673–86.

Dawson AJ, Homer CS. How does the mining industry contribute to sexual and reproductive health in developing countries? A narrative synthesis of current evidence to inform practice. J Clin Nurs. 2013;22:3597–609.

Clift S, Anemona A, Watson-Jones D, Kanga Z, Ndeki L, Changalucha J, Gavyole A, Ross DA. Variations of HIV and STI prevalences within communities neighbouring new goldmines in Tanzania: importance for intervention design. Sex Transm Infect. 2003;79:307–12.

Lightfoot E, Maree M, Ananias J. Exploring the relationship between HIV and alcohol use in a remote Namibian mining community. Afr J AIDS Res. 2009;8:321–7.

JJ X, Wang N, Lu L, Pu Y, Zhang GL, Wong M, ZL W, Zheng XW. HIV and STIs in clients and female sex workers in mining regions of Gejiu City, China. Sex Transm Dis. 2008;35(6):558–65.

Auvert B, Ballard R, Campbell C, Carael M, Carton M, Fehler G, Gouws E, MacPhail C, Taljaard D, Van Dam J, et al. HIV infection among youth in a South African mining town is associated with herpes simplex virus-2 seropositivity and sexual behaviour. AIDS. 2001;15:885–98.

Desmond N, Allen CF, Clift S, Justine B, Mzugu J, Plummer ML, Watson-Jones D, Ross DA. A typology of groups at risk of HIV/STI in a gold mining town in north-western Tanzania. Soc Sci Med. 2005;60(8):1739–49.

Corno L, De Walque D. Mines, migration and HIV/AIDS in Southern Africa. J Afr Econ. 2012;21:465–98.

Rees D, Murray J, Nelson G, Sonnenberg P. Oscillating migration and the epidemics of silicosis, tuberculosis, and HIV infection in South African gold miners. Am J Ind Med. 2010;53(4):398–404.

Weine SM, Kashuba AB. Labor migration and HIV risk: a systematic review of the literature. AIDS Behav. 2012;16:1605–21.

D’Souza M, Karkada S, Somayaji G, Venkatesaperumal R. Women’s well-being and reproductive health in Indian mining community: need for empowerment. Reprod Health. 2013;10:1–12.

D’Souza M, Karkada S, Somayaji G. Factors associated with health-related quality of life among Indian women in mining and agriculture. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2013;11:1–9.

D’Souza M, Somayaji G, Subrahmanya N. Determinants of reproductive health and related quality of life among Indian women in mining communities. J Adv Nurs. 2011;67:1963–75.

Monaldi FJ. The mining boom in Latin America. ReVista (Cambridge). 2014;13(2):6.

Chaparro Ávila E. La pequeña minería y los nuevos desafíos de la gestión pública [Small-scale mining and the new challenges of governance], vol. 70. Santiago: Comisión Económica para América Latina y el Caribe (CEPAL) - UN; 2004.

IMF Primary Commodity Prices [http://www.imf.org/external/np/res/commod/index.aspx].

Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean. Natural resources: status and trends towards a regional development agenda in Latin America and the Caribbean. Santiago: Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC) - UN; 2013.

Walter M. Extractives in Latin America and the Caribbean: the basics. Washington DC: Inter-American Development Bank; 2016.

Sociedad Peruana de Derecho Ambiental. La realidad de la minería ilegal en países amazónicos [The reality of illegal mining in Amazon countries]. Lima: Sociedad Peruana de Derecho Ambiental (SPDA); 2014.

Delgado Ramos GC. La gran minería en América Latina, impactos e implicaciones [The large-scale mining in Latin America, impacts and implications]. Acta Sociol [Mexico]. 2010;54:17–47.

Gómez ET, González ML. Auge minero y desindustrialización en América Latina [Mining boom and deindustrialization in Latin America]. Revista de Economía Institucional. 2017;19(37):133-46.

Porto M. A tragédia da mineração e do desenvolvimento no Brasil: desafios para a saúde coletiva [The tragedy of mining and development in Brazil: public health challenges]. Cad Saude Publica. 2016;32(2):e00211015. https://doi.org/10.1590/0102-311X00211015.

Cordy P, Veiga MM, Salih I, Al-Saadi S, Console S, Garcia O, Mesa LA, Velásquez-López PC, Roeser M. Mercury contamination from artisanal gold mining in Antioquia, Colombia: the world’s highest per capita mercury pollution. Sci Total Environ. 2011;410:154–60.

Bebbington A (ed.). Social conflict, economic development and the extractive industry: evidence from South America. London: Routledge; 2012.

Comisión Interamericana de Derechos Humanos. Pueblos indígenas, comunidades afrodescendientes y recursos naturales: protección de derechos humanos en el contexto de actividades de extracción, explotación y desarrollo [Indigenous peoples, Afro-Colombian communities and natural resources: human rights protection in the context of mining activities, exploration and development]. Washington DC: Comisión Interamericana de Derechos Humanos (CIDH); 2015.

International Labour Organization. Girls in mining: research findings from Ghana, Niger, Peru and United Republic of Tanzania. Geneva: International Labour Organization (ILO); 2007.

Heemskerk M. Self-employment and poverty alleviation: women’s work in artisanal gold mines. Hum Organ. 2003;62:62–73.

Drewry J, Shandro J, Winkler MS. The extractive industry in Latin America and the Caribbean: health impact assessment as an opportunity for the health authority. Int J Public Health. 2017;62(2):253–62.

Garcia-Moreno C, Pallitto C, Devries K. Global and regional estimates of violence against women: prevalence and health effects of intimate partner violence and non-partner sexual violence. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2013.

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. The Millennium Development Goals Report 2015. New York: United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division; 2015.

Sedgh G, Bearak J, Singh S, Bankole A, Popinchalk A, Ganatra B, Rossier C, Gerdts C, Tunçalp Ö, Johnson BR. Abortion incidence between 1990 and 2014: global, regional, and subregional levels and trends. Lancet. 2016;388:258–67.

Arksey H, O'Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32.

Daudt HM, van Mossel C, Scott SJ. Enhancing the scoping study methodology: a large, inter-professional team’s experience with Arksey and O’Malley’s framework. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2013;13(1):48.

Pereira CA, Périssé AR, Knoblauch AM, Utzinger J, de Souza Hacon S, Winkler MS. Health impact assessment in Latin American countries: current practice and prospects. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 2017(65):175–85.

González N, Rodríguez-Acosta A. Epidemiología de las enfermedades de transmisión sexual en la zona minera Las Claritas, estado Bolívar, Venezuela. Investig Clin. 2000;41(2):81–91.

Astete J, Gastañaga MC, Fiestas V, Oblitas T, Sabastizagal I, Lucero M, Abadíe JM, Muñoz ME, Valverde A, Suarez M. Enfermedades transmisibles, salud mental y exposición a contaminantes ambientales en población aledaña al proyecto minero Las Bambas antes de la fase de explotación, Perú 2006 [Comunicable diseases, mental health and exposure to environmental pollutants in population living near Las Bambas mining project before exploitation phase, peru 2006]. Rev Peru Med Exp Salud Publica. 2010;27:512–9.

Faas L, Rodríguez-Acosta A, Echeverría de Pérez G. HIV/STD transmission in gold-mining areas of Bolívar State, Venezuela: interventions for diagnosis, treatment, and prevention. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 1999;5:58–65.

Miranda AE, Merçon-de-Vargas PR, Corbett CE, Corbett JF, Dietze R. Perspectives on sexual and reproductive health among women in an ancient mining area in Brazil. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2009;25(2):157–61.

Orellana ER, Alva IE, Cárcamo CP, García PJ. Structural factors that increase HIV/STI vulnerability among indigenous people in the Peruvian Amazon. Qual Health Res. 2013;23(9):1240–50.

Palmer CJ, Validum L, Loeffke B, Laubach HE, Mitchell C, Cummings R, Cuadrado RR. HIV prevalence in a gold mining camp in the Amazon region, Guyana. Emerg Infect Dis. 2002;8(3):330–1.

Santos E, Loureiro E, de Jesus I, Brabo E, da Silva R, Soares M, Câmara V, de Souza M, Branches F. Diagnóstico das condições de saúde de uma comunidade garimpeira na região do Rio Tapajós, Itaituba, Pará, Brasil, 1992 [Diagnosis of the health conditions of a gold mining community in the Tapajós River region, Itaituba, Para, Brazil, 1992]. Cad Saude Publica. 1995;11:212–25.

Seguy N, Denniston M, Hladik W, Edwards M, Lafleur C, Singh-Anthony S, Diaz T. HIV and syphilis infection among gold and diamond miners—Guyana, 2004. West Indian Med J. 2008;57:444–9.

Souto FJ, Fontes CJ, Gaspar AM. Prevalence of hepatitis B and C virus markers among malaria-exposed gold miners in Brazilian Amazon. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2001;10:388–94.

Souto FJ, Fontes CJ, Gaspar AM, Lyra LG. Hepatitis B virus infection in immigrants to the southern Brazilian Amazon. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1998;92:282–4.

Castro-Arroyave D, Patino S, Gómez N, Gómez L, Ospina D, Osorio JD, Galvis R, Rojas C. Formación de líderes para la prevención del VIH: percepciones y conocimientos sobre el virus en un contexto minero de Colombia. Desacatos. 2016;52:128–43.

Vargas-Riaño E, Becerra-Posada F, Tristán M, Becerril-Montekio V. Maternal health research outputs and gaps in Latin America: reflections from the mapping study. Glob Health. 2017;13(1):74.

Ward B, Strongman J, Eftimie A, Heller K. Gender-sensitive approaches for the extractive industry in Peru: improving the impact on women in poverty and their families—guide for improving practice. Washington, DC: World Bank; 2011.

Siegel S, Veiga MM. The myth of alternative livelihoods: artisanal mining, gold and poverty. Int J Environ Pollut. 2010;41:272–88.

Maconachie R. Re-agrarianizing livelihoods in post-conflict Sierra Leone? Mineral wealth and rural change in artisanal and small-scale mining communities. J Int Dev. 2011;23(8):1054–67.

Hinton J, Veiga M, Beinhoff C. Women and artisanal mining: gender roles and the road ahead. In: Hilson G, editor. The socio-economic impacts of artisanal and small-scale mining in developing countries. Avereest: AA Balkema, Sweets Publishers; 2003.

Jenkins K. Women, mining and development: an emerging research agenda. Extractive Ind Soc. 2014;1:329–39.

Kuramoto JR. Artisanal and informal mining in Peru. London: International Institute for Environment and Development; 2001.

Chaparro Avila E, Lardé J. El papel de la mujer en la industria minera de Centroamérica y el Caribe [The role of women in the mining industry of Central America and the Caribbean], vol. 144. Santiago de Chile: Comisión Económica para América Latina y el Caribe (CEPAL) - UN; 2009.

Campbell C, Williams B. Beyond the biomedical and behavioural: towards an integrated approach to HIV prevention in the southern African mining industry. Soc Sci Med. 1999;48(11):1625–39.

Organización Internacional del Trabajo, Gobierno de Chile, SEREMI Tarapacá: Informe y análisis de la encuesta Vida de mineros: Condiciones de trabajo y salud sexual de mineros chilenos en la región de Tarapacá [Report and analysis of the survey life of miners: working conditions and sexual health of Chilean miners in the region of Tarapacá]. Santiago de Chile: Organización Internacional del Trabajo (OIT); 2015.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge Todd M. Bear, PhD, MPH, for his constructive comments on the manuscript.

Funding

The authors declare that this study did not receive any specific funding.

Availability of data and materials

No datasets were generated or analyzed for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Both authors participated in conceiving and designing the study, as well as in the interpretation of findings. JWG carried out the database search and collection and analysis of references and drafted the manuscript. PD reviewed the papers selected and critically reviewed the manuscript for important intellectual content and editing. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Wilches-Gutierrez, J., Documet, P. What is known about sexual and reproductive health in Latin American and Caribbean mining contexts? A systematic scoping review. Public Health Rev 39, 1 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40985-017-0078-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40985-017-0078-z