Abstract

Background

To compare a near decade of follow-up, newer control cohort data, use of both the societal and third party insurer cost perspectives, and integration of unilateral/bilateral therapy on the comparative effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of intravitreal ranibizumab therapy for neovascular, age-related macular degeneration (AMD).

Methods

Value-Based Medicine®, 12-year, combined-eye model, cost-utility analysis employing MARINA and HORIZON clinical trial data. Preference-based comparative effectiveness outcomes were quantified in (1) QALY (quality-adjusted life-year) gain, and (2) percent improvement in quality-of-life, while cost-effectiveness outcomes were quantified in (3) the cost-utility ratio (CUR) and financial return-on-investment (ROI) to society.

Results

Using MARINA and HORIZON trial data and a meta-analysis control cohort after 24 months, ranibizumab therapy conferred a combined-eye patient value (quality-of-life) gain of 16.3%, versus 10.4% found in 2006. The two-year direct ophthalmic medical cost for ranibizumab therapy was $46,450, a 33.8% real dollar decrease from 2006. The societal cost perspective CUR was −$242,920/QALY, indicating a $282,517 financial return-on-investment (ROI), or 12.3%/year to society for direct ophthalmic medical costs expended. The 3rd party insurer CUR ranged from $21,199/QALY utilizing all direct, medical costs, to $69,591/QALY using direct ophthalmic medical costs.

Conclusions

Ranibizumab therapy for neovascular AMD in 2015, considering treatment of both eyes, conferred greater patient value gain (comparative effectiveness) and improved cost-effectiveness than in 2006, as well as a large monetary return-on-investment to the Gross Domestic Product and nation’s wealth. The model herein integrates important novel features for neovascular age-related macular degeneration, vitreoretinal cost effectiveness analyses, including: (1) treatment of both eyes, (2) a long-term, untreated control cohort, and (3) the use of societal costs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Intravitreal ranibizumab therapy has been shown to be an effective treatment for minimally classic/occult [1, 2] and classic [3] subfoveal choroidal neovascularization occurring with neovascular age-related macular degeneration (NVAMD) in well designed and executed Level 1 [4] clinical trials. Ranibizumab (Lucentis®) is a recombinant humanized, IgG1 kappa isotype, monoclonal antibody fragment designed for intraocular use [5]. It binds to and inhibits the biologic activity of human vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGF-A), a molecule believed to be primarily responsible for the development of the choroidal neovascularization associated with NVAMD.

A number of healthcare economic studies, including cost-utility analyses, cost-effectiveness analyses and cost-benefit analyses, have addressed the use of ranibizumab for the treatment of NVAMD [6,7,8,9,10,11,12]. Unfortunately, even with sensitivity analyses [13], very few cost-utility analyses (also called cost-effectiveness analyses by some [13]) are comparable due to the use of different utilities, dissimilar utility respondents, differing cost perspectives, diverse costs bases, unlike discounting and so forth [14]. The Center for Value-Based Medicine® has estimated that over 27,000,000 different, input variable combinations can be used in a single cost-utility analysis [4]. Even one different input can make a major difference in the outcome [4, 14].

Value-Based Medicine® (VBM) [4, 14,15,16,17] is a methodology of cost-utility analysis employing standardized inputs to determine the patient value gain and financial value gain conferred by healthcare interventions. Patient value gain is quantified by improvement in length-of-life and/or quality-of-life; it is measured in QALY (quality-adjusted life-year) gain and percent patient value gain. The intervention which confers the greatest patient value has the greatest comparative effectiveness. VBM integrates financial value gain using the resources expended for the patient value gain in terms of the cost-utility ratio ($/QALY, or dollars expended per QALY gained), and the dollar return-on-investment (ROI) to society for the interventional, direct medical costs expended (cost-benefit ratio). VBM [4, 14,15,16,17] standardizes cost-utility analysis variables by typically utilizing: (1) time tradeoff utilities, (2) patient utility respondents, (3) the average national Medicare Fee Schedule, and (4) both societal and 3rd party insurer cost perspectives.

The Panel on Cost-Effectiveness in Health and Medicine [13, 18] has recommended that cost-utility analyses use the societal cost perspective. While the literature is replete with cost-utility analyses touting the cost-effectiveness of healthcare interventions, most do not address the entirety of societal costs affected by healthcare interventions [14].

Beauchamp and colleagues [19] have long advocated that medicine’s business is the production of patient value and economic return. We agree that healthcare economic analyses should ideally provide accurate assessments of, not only conferred patient value and the societal cost-utility, but also the financial ROI accrued to society and to the GDP (Gross Domestic Product) [14].

In 2008, we published a third party insurer, second-eye model, cost-utility analysis (using 2006 data and costs) on ranibizumab for the treatment of neovascular AMD utilizing MARINA (Minimally classic/occult trial of the Anti-VEGF antibody Ranibizumab In the treatment of Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration) Study data [9]. Longer treatment data, improved control cohort data [20] and societal cost data [21, 22], however, have since become available that dramatically alter the patient value gain. Financial ROI was not addressed in our 2008 report [9]. Thus, we believe it important to present these data in a cost-utility analysis demonstrating recent patient value gain and financial value gain for ranibizumab therapy for AMD. These will be compared with 2006 data [9] that are available.

Methods

The MARINA and HORIZON trials

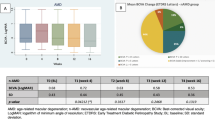

The MARINA Trial was a Phase III, 24-month, randomized clinical trial comparing intravitreal ranibizumab therapy with a 0.3 mg dose, a 0.5 mg dose, or sham therapy for neovascular AMD. The study parameters and cost-utility analysis assumptions utilized herein are shown in Table 1. We did not analyze 0.3 mg data since the 0.5 mg dose was the one approved for use by the Food and Drug Administration [5].

At randomization, mean vision in the MARINA Trial was 20/80 − 1 in both the 0.5 mg ranibizumab cohort and sham control cohort. By the end of 24 months, a mean 22 intravitreal ranibizumab injections were administered in the treatment cohort [1, 9]. At this time, the HORIZON (Open-Label Extension Trial of Ranibizumab for Choroidal Neovascularization Secondary to Age-Related Macular Degeneration) extension study of the MARINA Trial was utilized to model the ranibizumab treatment cohort from 25 to 48 months, after which a LOCF (last observation carried forward) methodology was used [23]. A mean 3.6 of injections were given from months 25 to 48. The timeline of the cost-utility model was 12 years, the average life expectancy of a participant in the MARINA Trial [1, 9]. The mean visions at different time intervals are shown in Table 2.

Control cohort

Sham cohort, MARINA trial [1], control data were used for 24 months, after which MARINA control cohort eyes were eligible for treatment with ranibizumab. Thus, control data for years 3–12 were derived from the meta-analysis of Shah and Del Priore [20], who used a double reciprocal (Lineweaver-Burke plot) methodology to assess the natural course of untreated subfoveal choroidal neovascularization associated with AMD. Shah and Del Priore plotted the variables of 1/(letters lost) versus 1/(time in months) (r2 = .9521) for the control groups of six major subfoveal, neovascular, AMD clinical trials [20]. The longest follow-up among these trials was 84 months. Shah and Del Priore [20] found the pattern of visual loss in eyes with subfoveal neovascular AMD to be uniform across the trials, with differences arising primarily from the time of entry into a trial.

Utilities

The time tradeoff vision utilities utilized herein, as in our previous report [9] were obtained with the approval of the Wills Eye Hospital Institutional Review Board from a cohort of over 1100 interviews of patients with ocular diseases. The utilities are reproducible and validated across age, level of education, ocular diseases, ethnicity, gender, income level, and the presence of comorbidities [24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31]. The disutilities from adverse events and their associated costs are integrated and treated in the same fashion as in our previous report [9].

Costs

Healthcare economic costs can be subdivided into: (1) direct medical costs (physician, facility and drug costs), (2) direct non-medical costs (caregiver, residence, and activities of daily living costs), and (3) indirect costs (decreased wages) [14]. In the previous ranibizumab cost-utility analysis [9] only 2006 U.S. nominal, direct ophthalmic medical costs were utilized. The current study uses 2015 U.S. societal costs in real dollars.

Direct non-ophthalmic medical costs

Not included previously [9], but included herein, are data from Javitt et al. [21] on Medicare’s excess, direct, non-ophthalmic medical costs associated with vision loss. These costs are attributable to increased depression, injury, SNF (skilled nursing facility) admissions, nursing home admissions, and other unexplained Medicare costs. They were adjusted to 2015 real dollars using the Medical Care component of the Consumer Price Index (CPI) [32]. These costs saved by ranibizumab therapy totaled $54,974 (Table 3).

Direct non-ophthalmic medical costs, direct non-medical costs and indirect medical costs only accrue for the second-eye model, since the first-eye model, fellow eye still has good vision. With Markov modeling (Treeage Software Inc., Williamstown, MA) and the data of Barbazetto et al. [33] 81.3% of the time during the 12-year model people have bilateral neovascular AMD (second-eye model). Thus the societal costs, excluding the direct ophthalmic medical costs, were all multiplied by 0.813. All direct ophthalmic costs are accrued, whether for the first eye or second eye treated.

Direct non-medical costs

Also absent in the previous report [9], but included herein, are the caregiver costs for AMD demonstrated by Schmier et al. [22] (Table 3). These were adjusted to 2015 U.S. dollars with the general CPI [22]. Schmier and colleagues [22] noted 27.7% of caregivers were paid and 72.3% were unpaid.

Salaries of previously unpaid caregivers freed-up to undertake paid employment as a result of ranibizumab therapy were treated as direct non-medical costs contributing to a gain in the GDP. The 27.7% of already paid caregiver salaries [22] decrease the GDP since these jobs are made unnecessary by better vision obtained from ranibizumab therapy. While displaced paid caregivers can obtain other jobs, we prefer a conservative analysis.

Indirect medical costs

The major, AMD indirect medical cost is loss of patient salary. Data from the Americans with Disabilities Household Economic Studies [34] show, between the decreased employment rate and decreased salary, a person with mild difficulty reading (vision <20/40) has an annual salary of $22,551, versus $18,915 for a person with severe difficult reading and $47,230 for a non-disabled person [35]. If a person with severe difficulty reading achieves >20/40 vision, the salary gain is ($47,230 − $18,913=) $28,317, while the gain from mild difficulty reading to >20/40 vision is ($47,230 − $22,551=) $24,679. Taking into account the proportions of people employed at different ages, the total salary gain from ranibizumab therapy was $9057.

Gross Domestic Product (GDP)

The GDP is a primarily a measure of the final goods and services produced within the country in a year [36]. It has four components: (1) consumer spending, (2) industry investment in new productive capabilities, (3) the excess of exports minus imports, and (4) the goods and services bought by the government. While a simplistic view, increasing the GDP increases the country’s wealth [36].

Net present value analysis

Net present value analysis weighs the costs versus the QALY gain, each reduced to present value by discounting. The Panel for Cost-Effectiveness in Health and Medicine [18] has recommended the 3% annual discount rate used herein.

Second-eye, first-eye and combined-eye models [9, 37]

The concept of first-eye and second-eye models was developed at the Center for Value-Based Medicine® based upon data from patients with ocular diseases. The first-eye model assumes vision in the fellow eye is normal; interventional patient value, or benefit, is usually not conferred until fellow eye vision deteriorates. The second-eye model assumes vision in first eye has already deteriorated. Thus, patient value gain is conferred from the initiation of therapy. The combined-eye model used for our base case is a weighted average of first- and second-eye models. Most ocular cost-utility models have used the second-eye model [6,7,8,9,10,11,12, 15, 17], suggesting a bias toward overstatement of patient value gains and greater cost-effectiveness.

Treeage Pro Healthcare, Excel Module 2014 software (Treeage Software Inc., Williamstown, MA) was utilized to assess the value gain for ranibizumab therapy in the first-eye and combined-eye models in our Sensitivity Analysis.

Results

Patient value gain

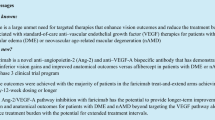

With the 12-year combined-eye model, the mean base case, patient value gain from intravitreal ranibizumab therapy utilizing the meta-analysis control cohort [20] from years 3 to 12 was 1.136 QALYs. This converted to a mean 16.3% quality-of-life improvement for the average patient, versus a 10.4% quality-of-life gain in 2006 [9]. The second-eye model accrued 1.372 QALYs, a 22.8% improvement in quality-of-life, versus 15.8% in 2006 [9].

Financial value gain

Direct ophthalmic medical costs

Our previous cost-utility analysis on MARINA data utilized a 3rd party insurer (direct ophthalmic medical costs) cost perspective with a 2006 average national Medicare Fee Schedule cost basis [9]. The 2006 direct ophthalmic medical cost was $52,652, while our comparable cost for the same drug and services in 2015 nominal dollars was $46,450, an 11.8% decrease since 2006. Adjusting for the Medical Care component of the CPI [32], the 2006 real dollar cost would be expected to rise to $70,161. Thus, over nine years from 2006 to 2015, adjusting with the Medical Care component of the CPI, the cost of two-year ranibizumab therapy in real dollars decreased by 33.8% (Table 4). Nonetheless, with the addition of ranibizumab treatment costs of $8120, simulating the HORIZON Trial in years 3 and 4 after baseline [23], and mean treatment costs of $24,287 for second eye conversion to neovascular AMD over 12 years [33], the total direct ophthalmic cost in 2015 is a more accurate $79,056.

Direct non-ophthalmic medical costs (Table 3)

The 12-year direct medical cost saved from the reduction of the depression, injury reduction, nursing home, SNF and so forth (Table 3) was $54,974 [21]. When this was subtracted from the direct ophthalmic medical cost of $79,056, the total direct medical cost was $24,082.

Direct non-medical costs. (Table 3)

The 12-year, direct non-medical cost saving for paid caregivers, who comprise 27.7% of caregivers, was $82,419 (Table 3). The $215,123 for unpaid caregivers corresponded to potential salary earned by freed-up, unpaid caregivers obtaining paid jobs [35]. This accrues to society and the GDP (Table 3).

Indirect medical costs: increased patient salaries (Table 3)

The 12-year cost associated with higher employment rates and improved salaries for ranibizumab-treated neovascular AMD patients with improved vision was $9057.

Total societal costs

The sum of costs accruing against the direct ophthalmic medical costs was (−$361,573). When the total direct ophthalmic medical cost of $79,056 was subtracted, the resultant dollars returned to society (or negative costs), primarily patients, was (−$282,517) (Table 3).

Physician fees

Physician fees in 2006 comprised 11.7% of direct ophthalmic medical costs and in 2015 comprised 5.6%. Ranibizumab costs in 2006 comprised 85.2% of costs, versus 91.9% of total costs in 2015 (Table 4).

Gross Domestic Product

The costs which contribute to the GDP are shown in Table 5 [36, 37]. Direct ophthalmic medical costs increase the GDP, but the direct non-ophthalmic medical costs obviated by ranibizumab therapy decrease the GDP. With the societal cost perspective, the overall contribution to the GDP over the 12 years of the model was $165,842, a 7.0% annual ROI referent to the $79,056 in direct medical costs expended for ranibizumab therapy. With the 3rd party insurer cost perspective, there was a negative ROI for the direct ophthalmic medical costs expended (Table 5).

Cost-utility analysis

An average cost-utility analysis compares an intervention to no therapy, while an incremental cost-utility analysis compares an intervention to other interventions [14].

Average CUR

The average, combined-eye, CUR with the MARINA Study societal cost perspective was (−$282,517/1.163=) (−243,921/QALY) (Table 5). A negative CUR indicates a dominant therapy in that it is less expensive than the alternative (observation) and at the same time it generates greater patient value than the alternative (observation herein). The CUR associated with the 3rd party insurer cost perspective using all direct medical costs (ophthalmic + non-ophthalmic) was ($24,082/1.136=) $21,199/QALY. With direct ophthalmic medical costs alone, the CUR was ($79,056/1.136=) $69,591/QALY. While the latter costs for NVAMD therapy over 12 years were higher than in 2006 [9], the earlier model did not include HORIZON trial and fellow eye treatment costs.

Incremental CURs

Incremental CURs are calculated from Value-Based Medicine®, published cost-utility data [15, 17] using a 3rd party insurer cost perspective (Table 6). The incremental CUR for ranibizumab therapy for NVAMD versus laser therapy was $20,643/QALY, while that referent to intravitreal pegaptanib was $3546/QALY and for photodynamic therapy was $16,044/QALY, all very cost-effective.

Sensitivity analysis

The sensitivity analyses were performed using the societal cost perspective, average cost-utility, and a 3% annual discount rate unless otherwise indicated (Table 7).

Eye models

The societal cost perspective, first-eye model conferred 0.680 QALY, a 9.8% improvement in quality-of-life, while the second-eye model conferred 1.372 QALYs, a 22.8% improvement in quality-of-life. The first-eye model, societal, CUR was (−$415,367)/QALY, while the second-eye model, societal, CUR was (−$205,971)/QALY. Since the costs were the same with each of these three variants, a less negative CUR indicates greater cost-effectiveness. In general, however negative CURs are not comparable, but rather indicate dominance.

Changes in cost

Increasing ranibizumab costs by 100%, the combined-eye, adding four additional ranibizumab injections annually and excluding caregiver costs all yielded cost-effective results (Table 7). Using costs from a treat-and-extend model [38], the 3rd party insurer cost perspective had a CUR of $45,995, similar to that of $48,036 using comparable costs in our current analysis.

Value gain

When the QALY gain decreased by 50% from years 5 to 12, the CUR was (−$462,960/QALY).

$50,000/QALY

For a societal cost perspective CUR of $50,000/QALY, the direct ophthalmic medical costs had to be increased to $339,317, a 329% increase over the current $$79,056. For a CUR of $100,000/QALY, the direct ophthalmic medical costs had to be increased to $432,021, a 401% increase over $79,056.

Comparisons

A comparison of patient value conferred by other drug classes, using a similar cost-utility model, shows the considerable value gain from ranibizumab therapy. Data from the Center for Value-Based Medicine® are shown in Table 8 [13, 16, 37, 39, 40]. Among the drug groups, only anti-depressants, β-blockers for glaucoma, and proton pump inhibitors match or exceed the patient value gain conferred by ranibizumab therapy for NVAMD. Ranibizumab value gain far exceeds that conferred by interventions for systemic arterial hypertension, hyperlipidemia, insomnia, erectile dysfunction, osteoporosis and allergy.

Discussion

Patient value

Our analysis demonstrates that ranibizumab therapy for NVAMD confers considerable patient value. This does not refer to cost, but rather the improvement in quality-of-life conferred by ranibizumab. Our previous analysis of patient value gain for the same intervention [9] demonstrated a 10.4% combined-eye model, value gain [9], versus 16.3% in the current analysis. With HORIZON trial data [23] and control cohort data from Shah and DelPriore [20], our 2015 analysis provides more reliable data than our 2006 data [9], which used a LOCF methodology from month 25 forward. It should be noted that ophthalmic patient utility gains tend to be similar in the United States, Canada and Europe [14, 24, 41, 42]. Utilities appear to be innate to human nature rather than one society [14]. Thus, the patient value gain data in this analysis can be integrated with the associated costs for ranibizumab therapy for NVAMD in another country and likely provide a valid cost-utility analysis for that country.

Costs

As used in the MARINA Study [1], intravitreal ranibizumab therapy yields a considerable financial return-on-investment to society and the GDP. The GDP is often regarded as a determinant of a nation’s wealth [36]. Ranibizumab therapy improves physical well-being, or human capital, which directly results in financial capital gain and also allows a dramatic decrease in caregiver costs.

The societal costs associated with many healthcare interventions are not well-defined, and only recently have those associated with vision loss and macular degeneration been identified [22, 23, 37, 39, 40, 43]. The majority of cost-utility analyses have not included caregiver costs, but they are especially relevant for untreated bilateral NVAMD [23].

Concerning employment and the decreased salary associated with disabilities, Americans with Disabilities Household Economic Studies data from the U.S. Census Bureau [34] are enlightening. Those with difficulty reading have lower mean earnings than those with hearing difficulty, a learning disability or in a wheelchair [34].

Cost-utility

The societal cost perspective generally produces an improved CUR for an intervention compared to the direct ophthalmic medical cost perspective [9, 37, 40]. This concept is demonstrated herein for ranibizumab (Table 5). Caregiver costs saved, improved salary and employment and direct medical costs obviated (depression, injury, facility admissions etc.) herein all accrue against the direct ophthalmic medical costs expended.

Cost-effectiveness standards

Healthcare interventions costing <$100,000/QALY are generally accepted as cost-effective in the U.S. [44] The World Health Organization [45] suggests an upper cost-effectiveness limit of 3× GDP per capita, or ~$164,000/QALY for the United States [46]. The use of ranibizumab in the societal cost perspective is very cost-effective by each of these criteria.

Potential study weaknesses

As with any analysis, there are potential inherent weaknesses in this study.

Neovascular AMD sub-types

The MARINA clinical trial assessed occult and minimally classic AMD variants, which together comprise 80% of neovascular AMD cases [47]. Ranibizumab therapy for classic neovascular AMD (20% of cases), as studied in the ANCHOR clinical trial [3], results in slightly greater, patient value gain than in the MARINA trial [1], suggesting the data in our analysis are actually conservative.

Absence of long-term clinical trial data

The absence of randomized clinical trial data after two years is a drawback, through HORIZON data provide treatment efficacy thru 48 months and Shah and DelPriore provide an excellent long-term control cohort [20]. The SEVEN-UP Study [48] followed ranibizumab-treated NVAMD patients for up to seven years, but the very small numbers of patients (~10% of those enrolled) likely introduce bias. Thus, we did not employ these data. The sensitivity analysis, however, demonstrates excellent cost-effectiveness even if ranibizumab loses 50% of its efficacy from months 49 to 144.

Unpaid caregiver costs

Unpaid caregivers may not obtain paid employment once freed-up to do so, but the sensitivity analysis addressed this as well. Even when all costs related to unpaid caregivers gaining paid employment are excluded, the CUR is still very cost-effective at $13,226/QALY.

Use of other drugs

Our intent herein was to compare the changes in preference-based comparative effectiveness and cost-utility for the same drug treating the same disease over a near decade. We thus did not perform cost-utility analyses on other VEGF inhibitors used for the treatment of NVAMD, such as aflibercept and bevacizumab.

Study strengths: differences from 2006 to 2015

Our paper utilized patient utilities and standardized VBM format [14]. In addition, four major changes were integrated into the current study that differentiate the results from our 2006 study costs [9]. These include: (1) a more reliable control cohort from Shah and DelPriore [20], (2) HORIZON extension trial treatment data [23], (3) societal costs from the studies of Javitt [21], Schmier [22] and Steinmetz [34], and (4) costs associated with the conversion of fellow eyes with atrophic AMD to NVAMD over the 12-year model time frame [33]. We are unaware that these unique parameters have been used together by other authors for assessing the cost-effectiveness of neovascular AMD therapy, especially in conjunction with primary utilities obtained from over 1100 ophthalmic patients. We believe they create a much more robust model than those used previously for the cost-effectiveness associated with treatment of NVAMD. As advances occur in healthcare interventions, they also take place in the economic evaluation of interventions. In this regard, it can be seen that a one-year cohort of 178,000 new neovascular AMD cases [49, 50] treated with ranibizumab will return over $50 billion to society over a 12-year period (Table 9).

Conclusions

In summary, the 2015 patient value gain conferred by, and costs associated with, ranibizumab therapy for NVAMD compare favorably with those from 2006. Longer-term treatment cohort follow-up, a more reliable control cohort, the inclusion of societal costs and a bilateral treatment model all result in a more robust 2015 analysis. The therapy provides great patient value than many common interventions across healthcare and also provides a considerable financial return-on-investment to society Changing patterns of therapy, such as increased use of a treat-and-extend model may result in more favorable cost-effectiveness yet for ranibizumab therapy.

Abbreviations

- VBM:

-

Value-Based Medicine

- AMD:

-

age-related macular degeneration

- NVAMD:

-

neovascular age-related macular degeneration

- GDP:

-

Gross Domestic Product

- LOCF:

-

last observation carried forward

- CUR:

-

cost-utility ratio

- ROI:

-

return on investment

- MARINA:

-

minimally classic/occult trial of the anti-VEGF antibody ranibizumab in the treatment of neovascular age-related macular degeneration

- VEGF:

-

vascular endothelial growth factor

- CPI:

-

consumer price index

References

Rosenfeld PJ, Brown DM, Heier JS, MARINA Study Group, et al. Ranibizumab for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. N Eng J Med. 2006;355:1419–31.

Boyer DS, Antoszyk AN, Awh CC, et al. MARINA Study Group. Subgroup analysis of the MARINA study of ranibizumab in neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology. 2007;114:246–52.

Brown DM, Kaiser PK, Michels M, Soubrane G, Heier JS, Kim RY, Sy JP. Schneider S; ANCHOR Study Group. Ranibizumab versus verteporfin for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1432–44.

Brown GC, Brown MM, Kertes P. Comparative effectiveness and cost-effectiveness analyses: 27,000,000 possible input variants. Evid Based Ophthalmol. 2011;12:52–7.

Lucentis (ranibizumab injection). Full Prescribing Information. South San Francisco, CA; Genentech; 2007. http://www.gene.com/gene/products/information/tgr/lucentis/insert.jsp. Accessed June 2015.

Cohen SY, Bremond-Gignac D, Quentel G, Mimoun G, Citterio T, Bisot-Locard S, Beresniak A. Cost-effectiveness sequential modeling of ranibizumab versus usual care in age-related macular degeneration. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2008;246:1527–34. doi:10.1007/s00417-008-0890-8 (Epub 2008 Jul 19).

Chakravarthy U, Harding SP, Rogers CA, for the IVAN Investigators, et al. A randomized controlled trial to assess the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of alternative treatments to Inhibit VEGF in age-related choroidal neovascularization (IVAN). Health Technol Assess. 2015;19:1–132.

Colquitt JL, Jones J, Tan SC, Takeda A, Clegg AJ, Price A. Ranibizumab and pegaptanib for the treatment of age-related macular degeneration: a systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess. 2008;12:iii-iv, ix-201.

Brown GC, Brown MM, Brown H, Peet JS. A value-based medicine analysis of ranibizumab (MARINA Study) for the treatment of subfoveal neovascular macular degeneration. Ophthalmology. 2008;115:1039–45.

Butt T, Lee A, Lee C, Tufail A, UK AMD EMR Study Group. The cost-effectiveness of initiating ranibizumab therapy in eyes with neovascular AMD with good vision: an economic model using real-world outcomes. BMJ Open. 2015;5(5):e006535. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006535.

Raftery J, Clegg A, Jones J, Tan SC, Lotery A. Ranibizumab (Lucentis) versus bevacizumab (Avastin): modeling cost effectiveness. Br J Ophthalmol. 2007;91:1244–6 (Epub 2007 Apr 12).

Fletcher EC, Lade RJ, Adewoyin T, Chong HV. Computerized Model of Cost-Utility Analysis for Treatment of Age-Related Macular Degeneration Corrected Proof, 20 October 2008. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2008.07.018. http://download.journals.elsevierhealth.com/pdfs/journals/0161-6420/PIIS0161642008007677.pdf. Accessed 25 Oct 2008.

Gold MR, Patrick DL, Torrance GW, Fryback DG, Hadorn DC, Kamlet MS, Daniels N, Weinstein MC. Identifying and valuing outcomes. In: Gold MR, Siegel JE, Russell LB, Weinstein MC, editors. Cost-effectiveness in health and medicine. New York: Oxford University Press; 1996. p. 82–134.

Brown MM, Brown GC, Sharma S. Evidence-based to value-based medicine. Chicago: AMA Press; 2005. p. 151–265.

Brown GC, Brown MM, Campanella J, Beauchamp GR, et al. The cost-utility of photodynamic therapy in eyes with neovascular age-related macular degeneration. A reappraisal with 5-year data. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;140:679–87.

Brown MM, Brown GC, Sharma S. Value-based medicine. A paradigm for quality pharmaceutical care. Drug Benefit Trends. 2006;18:285–9.

Brown GC, Brown MM, Brown HC, et al. A value-based medicine comparison of interventions for subfoveal neovascular macular degeneration. Ophthalmology. 2007;114:1170–8.

Siegel JE, Weinstein MC, Russell LB, Gold MR. Panel on cost-effectiveness in health and medicine: recommendations for reporting cost-effectiveness analyses. JAMA. 1996;276:1339–41.

Beauchamp GR, Bane MC, Stager DR, Berry PM, Wright WW. A value analysis model applied to the management of amblyopia. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1999;97:349–67 (discussion 367–72).

Shah AP, Del Priore LV. Progressive visual loss in subfoveal exudation in age-related macular degeneration: a meta-analysis using Lineweaver-Burke plots. Am J Ophthalmol. 2007;143:83–9.

Javitt JC, Zhou Z, Willke RJ. Association between visual loss and higher medical care costs in medicare beneficiaries. Ophthalmology. 2007;114:238–45.

Schmier JK, Halpern MT, Covert D, Delgado J, Sharma S. Impact of visual impairment on use of care giving by individuals with age-related macular degeneration. RETINA. 2006;26:1056–62.

Singer MA, Awh CC, Sadda S, Freeman WR, Antoszyk AN, Wong P, Tuomi L. HORIZON an open-label extension trial of ranibizumab for choroidal neovascularization secondary to age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology. 2012;119:1175–83. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2011.12.016 (Epub 2012 Feb 4).

Brown MM, Brown GC, Sharma S, et al. Utility values associated with blindness in an adult population. Br J Ophthalmol. 2001;85:327–31.

Brown GC. Vision and quality of life. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1999;97:473–512.

Brown GC, Sharma S, Brown MM, Kistler J. Utility values associated with age-related macular degeneration. Arch Ophthalmol. 2000;118:47–51.

Brown MM, Brown GC, Sharma S, et al. Quality of life with visual acuity loss from diabetic retinopathy and age-related macular degeneration. Arch Ophthalmol. 2002;120:481–4.

Sharma S, Brown GC, Brown MM, et al. Validity of the time trade-off and standard gamble methods of utility assessment in retinal patients. Br J Ophthalmol. 2002;86:493–6.

Brown GC, Brown MM, Sharma S. Difference between ophthalmologist and patient perceptions of quality-of-life associated with age-related macular degeneration. Can J Ophthalmol. 2000;35:27–32.

Brown MM, Brown GC, Sharma S, et al. Quality-of-life and systemic comorbidities in patients with ophthalmic disease. Br J Ophthalmol. 2002;86:8–11.

Brown GC, Brown MM, Sharma S, et al. The reproducibility of ophthalmic utility values. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 2001;99:199–203.

Bureau of Labor Statistics. Databases, tables and calculators by subject. Consumer Price Index, Medical Care. From the Internet. Accessed 05 July 15.

Barbazetto IA, Saroj N, Wong P, Ho AC, Freund KB. Incidence of new choroidal neovascularization in fellow eyes of patients treated in the MARINA and ANCHOR trials. Am J Ophthalmol. 2010;149:939–46.

Steinmetz E. Household economic studies. Current population reports. Americans with disabilities: 2002, U.S. Department of Commerce Economics and Statistics Administration. U.S. Census Bureau. http://www.bls.gov/news.release/ocwage.htm. DC, 2006, pp. 1–33.

Bureau of Labor Statistics. Occupational employment and wages news release. http://www.bls.gov/news.release/ocwage.htm. Accessed 6 July 2015.

Calculating GDP—The expenditure approach. http://www.mindtools.net/GlobCourse/formula.shtml. Accessed 14 Oct 08.

Brown MM, Brown GC, Brown HC, Irwin B, Roth Z. Comparative effectiveness and cost-effectiveness analyses of VEGF-A inhibitor and 90Sr brachytherapy for neovascular macular degeneration. Evid Based Ophthalmol. 2009;10:107–22.

Rayess N, Houston SK 3rd, Gupta OP, et al. Treatment outcomes after 3 years in neovascular age-related macular degeneration using a treat-and-extend regimen. Am J Ophthalmol. 2015;159:3–8.

Brown GC, Brown MM, Kertes P. Value-based medicine, cost-utility analysis the value of commonly-used pharmaceuticals. Evid Based Ophthalmol. 2009;10:107–22.

Brown GC, Brown MM, Menezes A, Busbee BG, Lieske HB, Lieske PA. Cataract surgery cost-utility revisited in 2012. A new economic paradigm. Ophthalmology. 2013;120:2367–76.

Sharma S, Oliver A, Bakal J, Hollands H, Brown GC, Brown MM. Utilities associated with diabetic retinopathy: results from a Canadian sample. Br J Ophthalmol. 2003;87:259–61.

Kobelt G, Jonsson B, Bergstrom A, Chen E, Linden C, Alm A. Cost-effectiveness analysis in glaucoma: what drives utility? Results from a pilot study in Sweden. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2006;84:363–71.

Brown GC, Brown MM, Lieske HB, Tran I, Turpcu A, Colman S. The societal costs associated with neovascular, age-related macular degeneration in the United States. RETINA 2015 Sep 29 (Epub ahead of print).

Laupacis A, Feeny D, Detsky AS, Tugwell PX. How attractive does a new technology have to be to warrant adoption and utilization? Tentative guidelines for using clinical and economic evaluations. CMAJ. 1992;146:473–81.

The World Health Organization. The World Health Report 2002—Reducing risks, promoting healthy life, pp 47–96. http://www.who.int/whr/2002/en/index.html. Accessed 18 March 2015.

Central Intelligence Agency. The World Factbook. Rank Order-GDP-per capita (PPP). https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-worldfactbook/rankorder/2004rank.html. Accessed 4 July 2009.

Olsen TW, Feng X, Kasper TJ, Rath PP, Steuer ER. Fluorescein angiographic lesion type frequency in neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology. 2004;111:250–5.

Bhisitkul RB, Desai SJ, Boyer DS, Sadda SR, Zhang K, SEVEN-UP Study Group. Seven-year outcomes in ranibizumab-treated patients in ANCHOR, MARINA, and HORIZON: a multicenter cohort study (SEVEN-UP). Ophthalmology. 2013;120:2292–9.

Klein R, Klein BEK, Tomany SC, et al. Ten-year incidence and progression of age-related maculopathy. The Beaver Dam Eye Study. Ophthalmology. 2002;109:1767–79.

Friedman DS, O’Colmain BJ, Munoz B, Eye Diseases Prevalence Research Group, et al. Prevalence of age-related macular degeneration in the United States. Arch Ophthalmol. 2004;122:564–72.

Authors’ contributions

Acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data: GCB, MMB, HBL. Drafting of manuscript and revising intellectual content: GCB, MMB, HBL, AT, YR. Final approval of manuscript: GCB, MMB, HBL, AT, YR. Accountable for manuscript accuracy and integrity: GCB, MMB. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

None.

Competing interests

Drs. G. Brown and M. Brown are stockholders in the Center for Value-Based Medicine®. Drs. A. Turpcu and Y. Rajput are employees of Genentech, Inc.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The MARINA trial received approval from the institutional review board at each of 96 study sites before the enrollment of patients. Patients provided written informed consent before determination of their full eligibility. The HORIZON study protocol was approved by the respective institutional review boards before study initiation, and all participating patients provided informed consent. The time tradeoff vision utilities utilized were obtained with the approval of the Wills Eye Hospital Institutional Review Board.

Funding

This study was funded through a grant from Genentech, Inc. to the Center for Value-Based Medicine.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Brown, G.C., Brown, M.M., Lieske, H.B. et al. The comparative effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of ranibizumab for neovascular macular degeneration revisited. Int J Retin Vitr 3, 5 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40942-016-0058-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40942-016-0058-3