Abstract

Background

Patient engagement in research refers to collaboration between researchers and patients (i.e., individuals with lived experience including informal caregivers) in developing or conducting research. Offering non-financial (e.g., co-authorship, gift) or financial (e.g., honoraria, salary) compensation to patient partners can demonstrate appreciation for patient partner time and effort. However, little is known about how patient partners are currently compensated for their engagement in research. We sought to assess the prevalence of reporting patient partner compensation, specific compensation practices (non-financial and financial) reported, and identify benefits, challenges, barriers and enablers to offering financial compensation.

Methods

We conducted a systematic review of studies citing the Guidance for Reporting the Involvement of Patients and the Public (GRIPP I and II) reporting checklists (October 2021) within Web of Science and Scopus. Studies that engaged patients as research partners were eligible. Two independent reviewers screened full texts and extracted data from included studies using a standardized data abstraction form. Data pertaining to compensation methods (financial and non-financial) and reported barriers and enablers to financially compensating patient partners were extracted. No formal quality assessment was conducted since the aim of the review is to describe the scope of patient partner compensation. Quantitative data were presented descriptively, and qualitative data were thematically analysed.

Results

The search identified 843 studies of which 316 studies were eligible. Of the 316 studies, 91% (n = 288) reported offering a type of compensation to patient partners. The most common method of non-financial compensation reported was informal acknowledgement on research outputs (65%, n = 206) and co-authorship (49%, n = 156). Seventy-nine studies (25%) reported offering financial compensation (i.e., honoraria, salary), 32 (10%) reported offering no financial compensation, and 205 (65%) studies did not report on financial compensation. Two key barriers were lack of funding to support compensation and absence of institutional policy or guidance. Two frequently reported enablers were considering financial compensation when developing the project budget and adequate project funding.

Conclusions

In a cohort of published studies reporting patient engagement in research, most offered non-financial methods of compensation to patient partners. Researchers may need guidance and support to overcome barriers to offering financial compensation.

Plain English summary

The term patient engagement in research is used to describe research that is conducted “with” patients, rather than “on” patients. It is important that researchers recognize patient partners for their time and expertise. In order to gain a better understanding of approaches to recognition for patient partners we reviewed published studies to: (1) assess how often financial compensation is reported, (2) identify how patient partners are reported as being compensated, and (3) understand what benefits, challenges, barriers and enablers might exist to offering financial compensation. We conducted a systematic review of articles citing the Guidance for Reporting the Involvement of Patients and the Public (GRIPP) guidelines. We included all study designs if patients were engaged as partners. Studies in which patients were participants only were excluded. Data collected included information about details of patient partner compensation (financial and non-financial practices) as well as challenges relating to financial compensation. Numerical data were analysed descriptively. Textual data were coded by two reviewers and collated into overarching themes. Our search identified 316 papers. Of these, 91% reported offering compensation to patient partners. Most common methods were acknowledgement (65%) and co-authorship (49%). Only 79 studies (25%) reported offering financial compensation to patient partners. Limited funding and lack of institutional guidance were identified as two key barriers that may be preventing researchers from offering financial compensation. Our review found that non-financial methods of compensation are reported more often than financial compensation. Researchers may require more support when offering financial compensation to patient partners.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Patient engagement in research—also commonly referred to as a patient and public involvement [1] or patient and public engagement [2]—refers to the active inclusion of individuals with lived experience of a health issue, including informal caregivers, family and friends [3], in the research process [4]. It is research carried out ‘with’ patients and not ‘on’, ‘about’ or ‘for’ them [5]. Patient engagement in research yields numerous benefits including improved study quality, better clinical trial recruitment, and alignment of research priorities with needs of the ultimate end user [6]. As a result, there is growing advocacy for patient engagement in health research [6,7,8].

Recognizing patient partner contributions by offering non-financial or financial compensation has been proposed as a strategy to encourage continued patient engagement and demonstrate that patient partner efforts are valued [9]. Feeling valued is crucial to fostering an inclusive team atmosphere, which plays a pivotal role in supporting sustained and active patient engagement in research [10, 11]. Patient partner recognition methods can be non-financial (e.g., co-authorship) or financial (e.g., honoraria). Financial compensation, in particular, can serve as a facilitator by addressing important barriers to engagement [12]. Without financial compensation, only patient partners with time and resources will be able to become patient partners. To support researchers in developing compensation strategies, several patient-oriented organizations have developed guidance documents encompassing both non-financial and financial methods [13,14,15,16]. In addition, some funding agencies have established guidelines to assist applicants in budgeting for engagement [15,16,17,18,19,20,21]. Despite available guidance and policies, little is known regarding how researchers recognize patient partners either non-financially or financially. Similarly, researcher attitudes on financial compensation including benefits, challenges, barriers and enablers remain unclear.

Given this significant knowledge gap, the aim of our systematic review was to answer the following research questions: How are researchers compensating patient partners for their contributions to research? What is the prevalence of reporting patient partner financial compensation? and What are researcher attitudes towards patient partner financial compensation, including perceived benefits, challenges, barriers and enablers to offering financial compensation? To address these research questions we assessed the prevalence of reporting patient partner compensation among published research that engaged patients as well as identified non-financial and financial methods of compensation, the monetary values of financial compensation, and any guidance documents reported as informing the approaches. The review findings provide a contemporary overview of compensation strategies to help researchers, and inform implementation strategies to better support patient partner compensation.

Methods

Our systematic review was conducted in accordance with methodology detailed in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions [22] and this report is prepared in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) reporting guidelines (Appendix 1) [23]. The protocol was published as part of a larger research program [24] and can be found on the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO ID: CRD42022303226). A patient partner (MS) was engaged in this study and engagement activities are reported using the Guidance for Reporting the Involvement of Patients and the Public (GRIPP2) [25] checklist (Appendix 2).

Search strategy and information sources

We identified studies that cited the Guidance for Reporting the Involvement of Patients and the Public (GRIPP 1 and 2) [25, 26] checklists to report engagement activities and outcomes. Using this forward citation search, we hypothesised that we were more likely to capture a cohort of studies that had engaged patients as partners than we would have with a broader search filter; previous studies have demonstrated a very low rate of reporting patient engagement in research overall [27], thus the specificity of a broad literature search would be exceedingly low rendering the review infeasible. Consequently, we chose studies that reference GRIPP or GRIPP2 as a specific, efficient, and targeted search strategy to identify a cohort of published studies that had engaged patients. The forward citation search was conducted using the Scopus and Web of Science databases on October 14, 2021. An information specialist (Lindsey Sikora, Health Sciences Research Librarian, University of Ottawa) was consulted when developing the forward citation search strategies. All included studies were necessarily published after the GRIPP I publication date (2011).

Eligibility criteria

We included studies that were written in English, reference the GRIPP checklists (I or II) [25, 26] and engaged or described engaging patients in health research, in which members of the public or patients (i.e., an individual with lived experience of a health condition as well as informal caregivers, including family, friends, or members of patient organizations) are engaged as partners (provided input, guidance, consultation on at least one element of the research process) [4].

Studies that engaged patients as partners as well as participants (i.e., subjects of research) were included in the review, while studies where patients were involved solely as research participants were excluded. Examples of research engagement include priority-setting, governance, developing the research question, identifying study outcomes, study design, informing statistical analysis, interpreting study findings and disseminating results [28]. We included all study designs (e.g., qualitative, quantitative, evidence synthesis, mixed-methods research). Studies that described the patient engagement in research component as a part of a larger research project were included. Studies that interviewed patients about their experiences as patient partners were excluded as patients were participants in the research [29]. Conference abstracts and commentaries were also excluded.

Selection process

All records identified by the literature search were uploaded to DistillerSR (a cloud-based software program that facilitates systematic reviews) (Evidence Partners Incorporated, Ottawa, Canada) [30]. After duplicate removal, reviewers (GF, TS, FA) independently screened full-text articles according to the pre-specified eligibility criteria. The screening process was piloted for the first 20 articles to ensure reliability between reviewers. A third reviewer (DAF or MML) was consulted if reviewers could not reach consensus. Reasons for exclusion were recorded using the PRISMA flow diagram.

Data collection process

Two reviewers (GF, TS) independently extracted data from studies included in the systematic review using a data extraction form in DistillerSR. Data extraction was piloted for the first five studies to ensure consistency. After piloting, the reviewers extracted data from sets of 20 studies and resolved conflicts between each set. A third reviewer (DAF or MML) was consulted if reviewers could not reach consensus. We did not contact authors for missing or additional information since the focus of this systematic review was on the reporting of patient partner compensation practices.

Data items

Extracted items included study characteristics (e.g., author information, source of funding), patient engagement characteristics (e.g., level of engagement, type of stakeholder engaged), details of patient partner compensation (e.g., non-financial and financial practices), and any reported benefits, challenges, barriers and enablers to financial compensation. The country of the corresponding author’s institutional location was also extracted. For the purposes of this review, we defined non-financial compensation as offering tokens of appreciation or services in exchange for patient partnership on a research project, and financial compensation as offering something of direct monetary value in exchange for their involvement [19, 31, 32]. Gifts or gift cards were considered financial compensation only when the value was informed by a formal conversion (i.e., 2 h of work at $25 per hour = $50 gift or gift card value) or where they were reported as being given as a substitute for monetary payment based on the work undertaken. Financial compensation practices were identified based on reports with no initial list of categories. Rather, categories were developed inductively based on the developing list of items. For example, financial compensation based on a fixed monetary value (irrespective of workload) was defined as honoraria. While reported variously as being paid cash, cheques or stipend, these approaches were grouped under the category of honoraria. Studies that explicitly reported offering a salary to patient partners were grouped under the category of salary. Patient engagement activities were categorized as Consult, Collaborate, and Empower levels of engagement in accordance with definitions developed by the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) [33]. It is important to note that studies could achieve more than one level of engagement if different activities took place at different stages of the same research study. Engagement activities were categorized as occurring at different stages of the research process (e.g., study design, data collection, data analysis), governance (i.e., member of a committee overseeing the research project), general priority setting (i.e., identifying research priorities to inform future research) or general outcome derivation (i.e., identifying outcomes to be captured in future studies). A full list of data extraction items can be found in Appendix 3.

Study risk of bias assessment

No formal quality assessment was conducted for included studies since the aim of the review is to describe the use and type of patient partner compensation.

Synthesis methods

Patient engagement and compensation details (e.g., stakeholders engaged, length of engagement, type of financial compensation offered) were created inductively and analyzed descriptively. Prevalence of reporting patient partner financial compensation was calculated. Qualitative data (reported benefits, challenges, barriers and enablers to patient partner compensation) were analyzed thematically in accordance with the 6-step approach developed by Braun and Clark [34]. Verbatim statements were extracted by two independent reviewers (GF, TS) and stored in an Excel file. Two independent reviewers (GF, SN) read through extracted verbatim statements and generated initial codes within each of the five domains (benefits, challenges, barriers, enablers, justification). Reviewers met regularly to resolve discrepancies between initial codes. Initial codes were collated into overarching themes and reoccurring themes were combined. The frequency of reported themes was recorded.

Subgroup analysis

Prespecified subgroup analyses of reporting patient partner financial compensation were performed according to funding (funded vs. non-funded) and level of engagement (Consult, Collaborate, Empower) [35]. Given that levels of engagement are ordered based on the level of impact that patient partners have on decision making, we compared studies based on the highest level of engagement reported. For example, studies that engaged patient partner’s at all three levels of engagement were in the same subgroup as studies that only engaged patient partners at the Empower level of engagement since both achieved Empower as the highest level of engagement. A post hoc subgroup analysis by country (comparing studies conducted in the United States, Canada and the United Kingdom with the remaining studies) was conducted following consultation with a group of patient partners (i.e., Ontario SPOR Support Unit Patient Partner Working Group). This was based on the hypothesis that studies conducted in the United States, Canada and the United Kingdom may be more likely to practice patient partner compensation given support from well-established national infrastructures (i.e., Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI), Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR), and National Institutes for Health and Care Research (NIHR) respectively). Subgroup proportions were compared using Chi-square tests.

Patient and public involvement

One patient partner (MS) informed project development (e.g. review proposals and protocols, identifying sources, research question generation) and provided feedback on project conduct (e.g., data extraction, interpretation). MS has a wealth of experience with various facets of patient engagement in research including experience with various methods of compensation. Monthly meetings occurred with MS to discuss research findings as the systematic review progressed. We co-developed a terms of reference document a priori to establish details of engagement (e.g., expectations, project goals, compensation). Our patient engagement in research plan was informed by INVOLVE’s Seven Core Principles of Engagement [36] and the CIHR Strategies for Patient Oriented Research (SPOR) Patient Engagement framework [3]. Co-authorship and financial compensation were agreed upon with the patient partner and offered as a method of acknowledgement according to the SPOR Evidence Alliance Patient Partner Appreciation Policy [13]. The aim of collaboration was to ensure that the patient perspective was considered throughout the project.

Results

Search results

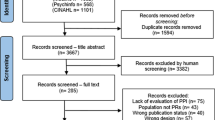

Our search retrieved 843 studies. After removing duplicates, 518 studies were screened and assessed for eligibility and a total of 316 studies were included in the systematic review. Screening results are presented using a PRISMA flow diagram (Fig. 1). A full list of included studies can be found in Appendix 4.

Study characteristics

Most corresponding authors were based in the United Kingdom (60%, n = 190) followed by Canada (16%, n = 51) and Denmark (5%, n = 15) (Appendix 5). Only one corresponding author was based in a Low- or Middle Income Country (LMIC) (South Africa). The earliest study was published in 2011 and the largest proportion of studies was published in 2020 (27%, n = 84), followed by 2021 (24%, n = 77) (Appendix 6). Most studies (84%, n = 265) were funded and 33 (12%) funded studies reported receipt of funding specifically to support patient engagement (Appendix 7A). Most funded studies received funding from government agencies (75%, n = 200) (Appendix 7B).

Patient engagement in research characteristics

Studies reported engaging a variety of stakeholders including patients (78%, n = 246), caregivers (35%, n = 111), and members of patient organizations (16%, n = 50) (Table 1). A median of five patient partners were reported for each study with a range of 1–705 patient partners. The study reporting 705 patient partners detailed three engagement efforts, including a conference event attended by patient partners [37].

Studies described engagement occurring at various stages across the research process including governance (24%, n = 76), funding acquisition (17%, n = 54), priority setting (17%, n = 52), study design (79%, n = 250), data collection (14%, n = 45), data analysis (43%, n = 137), dissemination of results (50%, n = 157), developing patient engagement plan (8%, n = 24), and ethics application development (0.3%, n = 1) (Table 2).We identified studies that engaged patient partners in general priority setting exercises (13%, n = 42) and general outcome derivation (5%, n = 16). Level of engagement in research reported were Consult (66%, n = 204), Collaborate (53%, n = 163), and Empower (14%, n = 44). We identified six studies (2%) that engaged patient partners at all three levels.

Reporting non-financial compensation practices

Of the 316 studies, 91% (n = 288) reported offering some type of compensation (i.e., non-financial or financial compensation) to patient partners. The most common reported method of non-financial compensation was informal acknowledgement on research outputs (e.g., acknowledgement section in publications, dissemination documents, presentations) (65%, n = 206) and co-authorship (49%, n = 156) (Table 3). Additional methods of non-financial compensation included facilitating patient partner attendance at conferences (7%, n = 2) and offering training opportunities (12%, n = 4). Twenty-eight (9%) studies reported not offering any form of non-financial compensation to patient partners.

Reporting financial compensation practices

Of the 316 studies, 25% (n = 79) reported offering financial compensation. Sixty-two (19%) reported offering financial compensation to all patient partners, 17 (5%) studies reported offering financial compensation to some patient partners, 32 (10%) explicitly reported that patient partners were not offered any form of financial compensation, and 205 studies (65%) did not report on financial compensation (Table 4).

We identified several reported methods of offering financial compensation including honoraria (e.g., cheques, stipend) (58%, n = 46), gift cards (16%, n = 13), salary (5%, n = 4) and scholarship (1%, n = 1). Sixteen (20%) studies reported offering task-based financial compensation (e.g., attended meeting, document review), while other studies used units of time (e.g., half-day meeting, per hour, full-time-equivalent salary rate) to inform the monetary value of financial compensation (14%, n = 11). Reported compensation rates ranged from $12 to $42 USD per hour or $31 to $94 USD for attendance at a half-day meeting (which at approximately 4 h would convert to $7.75–23.50 USD per hour) (Table 4). However, the majority of studies in which financial compensation was provided did not report the monetary value of financial compensation (72%, n = 57). In terms of payment frequency, thirteen (16%) studies reported providing financial compensation as a one-time payment, four (5%) studies paid patient partners immediately after completion of a task, and one (1%) study provided patient partners with an annual payment [38]. Most studies (77%, n = 61) did not report on payment frequency.

The most referenced documents used to inform financial compensation strategies were developed by the NIHR and INVOLVE (n = 22) including Payment and Recognition for Public Involvement [15], Policy on payment of fees and expenses for members of the public actively involved with Involve [39], and Recognition payments for public contributors [40]. Five studies used local minimum wage rates or national costs of living to inform the monetary value of financial compensation offered to patient partners.

Subgroup analysis

Studies that reported receipt of funding were significantly more likely to report financial compensation of patient partners when compared to studies that did not receive funding or did not report funding (\({\chi }^{2}\)=6.614, p < 0.01).Additionally, there was a significant difference in reporting patient partner financial compensation between studies that engaged patients at different levels (Consult, Collaborate and Empower) (\({\chi }^{2}\)= 42.41, p < 0.01). This finding suggests that reporting patient partner financial compensation and the level at which patients were engaged, are not independent of each other. Indeed, 42% (n = 47) of studies that achieved Consult as the highest level of engagement (n = 111) reported offering financial compensation to all or some patient partners, compared to 67% (n = 49) of studies that achieved Collaborate as the highest level of engagement (n = 73) and 95% (n = 18) of studies that achieved Empower as the highest level of engagement (n = 19).

A post-hoc subgroup analysis of studies where the corresponding author was based in Canada, United Kingdom and United States compared to studies where corresponding authors were based elsewhere found no significant difference in reporting patient partner financial compensation (\({\chi }^{2}\)=0.669, p = 0.41).

Benefits, challenges, barriers and enablers of financial compensation

A total of 32 studies (10%) reported benefits, challenges, barriers or enablers of financial compensation. The most common themes indicating benefits of financially compensating patient partners were “support patient partner participation” and “facilitate long term engagement across the research project”, since offering financial compensation can enable patient partners to allocate more time to the research project (e.g., attending more team meetings) (Table 5). One identified theme indicating a challenge to patient partner financial compensation was “financial payments can jeopardize disability or social security payments or impact income tax rates” since financial compensation can impact other income sources. Two themes indicating common barriers to offering financial compensation were “budget constraints” or “lack of funding for the study” and “lack of an institutional policy or guidance document” to inform compensation strategies.

Discussion

We conducted this systematic review to enhance our understanding of how patient partner recognition and compensation practices are reported, with the aim of providing valuable support to the research community in making informed decisions and formulating policies regarding patient compensation. We found that, among studies citing the GRIPP or GRIPP2 reporting guidelines, the majority of studies involving patients in research report non-financial compensation, while only a minority report financial compensation for patients.

The most common reported methods of non-financial compensation were informal acknowledgement and co-authorship. The level of reported co-authorship was much higher than levels reported in the literature, and was consistent with the highest levels of co-authorship reported in this journal [41]. Indeed, a review of systematic reviews published between 2011 and 2020 identified only 37 reviews that included a patient partner co-author [42]. Our results are, however, in line with previous research that found that acknowledgement was more common than co-authorship, even within the field of participatory research [43]. Although non-financial compensation (e.g. authorship or acknowledgements) was reported more frequently than financial compensation, we would also note drawbacks and potential threats to this approach. For instance, while there are academic career benefits from co-authorship for research team members, patient partners engage in research for different reasons and may not see the benefits or disadvantages of authorship in the same way. In some instances, co-authorship may even be refused by patient partners with lived experience of a stigmatized condition [44].

In terms of financial compensation, we identified substantial variation in the monetary value assigned, with reported compensation rates ranging from $12 to $42 USD per hour and $31 to $94 USD for attendance at a half-day meeting. We also found an association between the reported level of engagement (e.g., Consult, Collaborate, or Empower) and the reporting of financial compensation [35]. While we were unable to examine the extent to which the level of engagement was associated with the compensation rates reported, this would be consistent with recommendations from various compensation guidance documents that suggest different compensation rates based on the roles of patient partners in the research project [16, 18, 45,46,47].

Among the studies that did report financial compensation, researchers identified two key benefits: fostering long-term patient engagement in research and serving as a tangible means to express appreciation for patient partners' contributions. Moreover, barriers reported included “budget constraints” or “lack of funding for the study”. This is consistent with our subgroup analysis findings that suggest that studies reporting receipt of funding were significantly more likely to report financial compensation of patient partners. Notably, 12% of studies that received funding explicitly reported funding to support patient engagement.

While offering financial compensation to patient partners can have a positive impact on their engagement and is encouraged by most patient-oriented organizations, our review also identified potential barriers and challenges in implementing such compensation. A key barrier we identified is the lack of institutional policies and guidance, which limits research teams' ability to offer financial compensation to patient partners. This finding aligns with the barriers identified by individuals who have experience as patient partners in research. In their work, Richards et al. emphasized the crucial role of institutions in supporting patient partner compensation [48], particularly in developing or modifying existing contractual agreements to accommodate patient partnerships and logistics of processing payments. Therefore, it is important for institutions to adopt compensation guidelines and establish effective payment procedures, which can assist researchers in offering financial compensation to patient partners.

When developing a compensation strategy it is important to consider potential threats of financial compensation. Indeed, two studies in our review reported that they deliberately did not offer financial compensation to ensure patient partners were free to express their thoughts without any pressures associated with receiving payments. Keeping financial compensation at a level that reflects appreciation and is approved by patient partners may address this challenge. We also identified “jeopardization of disability or social security payments” as a significant risk of offering financial compensation, which further highlights the importance of considering patient partner preferences and circumstances. By carefully considering these benefits and threats of financial and non-financial compensation, researchers and patient partners can co-develop a compensation strategy that appropriately balances recognition, respect for autonomy, and potential threats associated with financial compensation.

Finally, we would suggest that it is imperative that researchers are transparent in reporting all aspects of their health research [49, 50] and reporting important details of patient engagement in research should be treated as no less important. Determining the essential patient engagement compensation elements to report, including financial aspects, requires further evaluation to incentivize reporting of patient partner compensation.

Limitations of the study

Our systematic review has certain limitations that should be acknowledged. First, our search strategy is limited to studies that cited the GRIPP reporting checklists, thus published patient engagement research that did not use the GRIPP checklists were not included. As stated above, it would not be feasible to conduct a broad literature search given the paucity of reporting patient engagement in health research [27]. Thus, it is crucial to consider that reporting of compensation practices may be different in studies that did not cite the GRIPP checklist. Second, the majority of included studies were written by researchers, which may introduce bias towards the researcher perspective. It is important to consider the experiences of patient partners themselves to better understand benefits, challenges, barriers and enablers to financial and non-financial compensation.

Conclusions

Our systematic review contributes to an area of patient engagement research where very little evidence exists. We found that non-financial compensation was more commonly reported than financial. Importantly, the details of financial compensation were rarely reported and highly variable although we did observe a signal that an increased level of engagement was associated with offering financial compensation. Our findings also suggest that adequate funding and budget guidance may support researchers in offering financial compensation to patient partners. Our work supports the need for the research community to better report patient engagement activities including patient compensation practices.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article and its additional files.

Abbreviations

- GRIPP:

-

Guidance for Reporting the Involvement of Patients and the Public

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses

- NIHR:

-

National Institutes for Health and Care Research

- CIHR:

-

Canadian Institutes of Health Research

- OSSU:

-

Ontario SPOR SUPPORT Unit

- SPOR:

-

Strategies for Patient-Oriented Research

References

Brett J, Staniszewska S, Mockford C, Herron-Marx S, Hughes J, Tysall C, et al. A systematic review of the impact of patient and public involvement on service users. Res Commun Patient. 2014;7(4):387–95.

Hickey G, Chambers M. Patient and public involvement and engagement: mind the gap. Health Expect Int J Public Particip Health Care Health Policy. 2019;22(4):607–8.

Government of Canada Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Strategy for Patient-Oriented Research—Patient Engagement Framework—CIHR [Internet]. 2014 [cited 2022 Jun 27]. Available from: https://cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/48413.html

Government of Canada Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Patient engagement—CIHR [Internet]. 2012 [cited 2022 Jun 15]. Available from: https://cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/45851.html

NIHR INVOLVE. Frequently asked questions: What is public involvement in research? [Internet]. Available from: https://www.nihr.ac.uk/health-and-care-professionals/engagement-and-participation-in-research/involve-patients.htm

Vat LE, Finlay T, Jan Schuitmaker-Warnaar T, Fahy N, Robinson P, Boudes M, et al. Evaluating the “return on patient engagement initiatives” in medicines research and development: a literature review. Health Expect. 2020;23(1):5–18.

Harrington RL, Hanna ML, Oehrlein EM, Camp R, Wheeler R, Cooblall C, et al. Defining Patient engagement in research: results of a systematic review and analysis: report of the ISPOR patient-centered special interest group. Value Health J Int Soc Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2020;23(6):677–88.

Fox G, Fergusson DA, Daham Z, Youssef M, Foster M, Poole E, et al. Patient engagement in preclinical laboratory research: a scoping review. EBioMedicine. 2021;70:103484.

Bellows M, Burns KK, Jackson K, Surgeoner B, Gallivan J. Meaningful and effective patient engagement: what matters most to stakeholders. Patient Exp J. 2015;2(1):18–28.

Smith E, Bélisle-Pipon JC, Resnik D. Patients as research partners; how to value their perceptions, contribution and labor? Citiz Sci Theory Pract. 2019;4(1):15.

An empirically based conceptual framework for fostering meaningful patient engagement in research-Hamilton-2018-Health Expectations-Wiley Online Library [Internet]. [cited 2022 Aug 4]. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/hex.12635

Richards DP, Jordan I, Strain K, Press Z. Patient partner compensation in research and health care: the patient perspective on why and how. Patient Exp J. 2018;5(3):6–12.

SPOR Evid Alliance 2019 Patient Partn Apprec Policy Protoc Tor SPOR Evid Alliance.

Government of Canada Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Considerations when paying patient partners in research-CIHR [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2022 Jun 15]. Available from: https://cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/51466.html

Payment and recognition for public involvement - INVOLVE [Internet]. [cited 2022 Jul 11]. Available from: https://www.invo.org.uk/resource-centre/payment-and-recognition-for-public-involvement/?print=print

Maritime SPOR SUPPORT Unit. Patient Partner Compensation and Reimbursement Policy. 2020.

US Department of Veterans Affairs. SERVE Toolkit for Veteran Engagement: Planning [Internet]. Available from: https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/for_researchers/serve/Section1-Planning.pdf

Strategy for Patient-Oriented Research (SPOR) SUPPORT Unit (AbSPORU). Patient Partner Appreciation Guidelines: Compensation in Research [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2022 Jul 19]. Available from: https://absporu.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Albertans4HealthResearch_Appreciation-Guidelines_Oct-2019_V6.0.pdf

SPOR Networks in Chronic Diseases and the PICHI Network. Recommendations on Patient Engagement Compensation [Internet]. 2018. Available from: https://diabetesaction.ca/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/TASK-FORCE-IN-PATIENT-ENGAGEMENT-COMPENSATION-REPORT_FINAL-1.pdf

PCORI. Financial compensation of patients, caregivers, and patient/caregiver organizations engaged in PCORI-funded research as engaged research partners [Internet]. 2015. Available from: https://www.pcori.org/sites/default/files/PCORI-Compensation-Framework-for-Engaged-Research-Partners.pdf

The Change Foundation. Should money come into it? A tool for deciding whether to pay patient-engagement participants [Internet]. 2015. Available from: https://hic.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/HIC-Should-money-come-into-it.pdf

Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions [Internet]. [cited 2022 Sep 3]. Available from: https://training.cochrane.org/handbook/current

The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews | The BMJ [Internet]. [cited 2022 Sep 3]. Available from: https://www.bmj.com/content/372/bmj.n71.long

Fox G, Lalu MM, Sabloff T, Nicholls S, Smith M, Stacey D, et al. Recognizing patient partner contributions to health research: a systematic review. Prep Submiss.

Staniszewska S, Brett J, Simera I, Seers K, Mockford C, Goodlad S, et al. GRIPP2 reporting checklists: tools to improve reporting of patient and public involvement in research. BMJ. 2017;2(358): j3453.

Staniszewska S, Brett J, Mockford C, Barber R. The GRIPP checklist: strengthening the quality of patient and public involvement reporting in research. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2011;27(4):391–9.

Fergusson D, Monfaredi Z, Pussegoda K, Garritty C, Lyddiatt A, Shea B, et al. The prevalence of patient engagement in published trials: a systematic review. Res Involv Engag. 2018;4:17.

Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Strategy for Patient-Oriented Research: Patient engagement [Internet]. 2019. Available from: https://cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/45851.html

Sharpening the focus: differentiating between focus groups for patient engagement vs. qualitative research | Research Involvement and Engagement | Full Text [Internet]. [cited 2022 Sep 8]. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40900-018-0102-6

DistillerSR [Internet]. [cited 2022 Sep 3]. DistillerSR | Systematic Review Software | Literature Review Software. Available from: https://www.evidencepartners.com/products/distillersr-systematic-review-software

Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Consideration when paying patient partners in research [Internet]. 2019. Available from: https://cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/51466.html

Greer AM, Buxton JA. A guide for paying peer research assistants: Challenges and opportunities [Internet]. 2016. Available from: https://pacificaidsnetwork.org/files/2016/05/A-guide-for-paying-peer-research-assistants-challenges-and-opportunities.pdf

INVOLVE. Briefing notes for researchers: public involvement in NHS, public health and social care research [Internet]. 2012 [cited 2022 Jul 18]. Available from: https://www.invo.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/9938_INVOLVE_Briefing_Notes_WEB.pdf

Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101.

International Association of Public Participation. Spectrum of Public Participation [Internet]. 2018. Available from: https://cdn.ymaws.com/www.iap2.org/resource/resmgr/pillars/Spectrum_8.5x11_Print.pdf

Organizing Engagement [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2022 Jun 27]. Core Principles for Public Engagement. Available from: https://organizingengagement.org/models/core-principles-for-public-engagement/

Kirwan JR, de Wit M, Frank L, Haywood KL, Salek S, Brace-McDonnell S, et al. Emerging guidelines for patient engagement in research. Value Health. 2017;20(3):481–6.

Vanderhout SM, Smith M, Pallone N, Tingley K, Pugliese M, Chakraborty P, et al. Patient and family engagement in the development of core outcome sets for two rare chronic diseases in children. Res Involv Engag. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40900-021-00304-y.pdf.

INVOLVE. Policy on payment of fees and expenses for members of the public actively involved with INVOLVE [Internet]. National Institute for Health Research; 2016 Feb [cited 2022 Jul 11]. Available from: https://www.invo.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/INVOLVE-internal-payment-policy-2016-final-1.pdf

Centre for Engagement and Dissemination—Recognition payments for public contributors [Internet]. [cited 2022 Jul 11]. Available from: https://www.nihr.ac.uk/documents/centre-for-engagement-and-dissemination-recognition-payments-for-public-contributors/24979

Oliver J, Lobban D, Dormer L, Walker J, Stephens R, Woolley K. Hidden in plain sight? Identifying patient-authored publications. Res Involv Engag. 2022;8(1):12.

Ellis U, Kitchin V, Vis-Dunbar M. Identification and reporting of patient and public partner authorship on knowledge syntheses: rapid review. J Particip Med. 2021;13(2): e27141.

Where Are the Missing Coauthors? Authorship Practices in Participatory Research-Sarna‐Wojcicki-2017-Rural Sociology-Wiley Online Library [Internet]. [cited 2023 Aug 9]. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/ruso.12156

Lessard D, Engler K, Toupin I, Routy JP, Lebouché B, I-Score Consulting Team. Evaluation of a project to engage patients in the development of a patient-reported measure for HIV care (the I-Score Study). Health Expect Int J Public Particip Health Care Health Policy. 2019;22(2):209–25.

CHILD-BRIGHT Network [Internet]. [cited 2022 Jul 19]. Compensation Guidelines. Available from: https://www.child-bright.ca/compensation-guidelines

BC Mental Health & Substance Use Services (BCMHSUS). Compensation and Remuneration for Patient/Client and Public Engagement with BCMHSUS [Internet]. 2021. Available from: http://www.bcmhsus.ca/allpageholding/Documents/Compensation%20Guidelines_Ver%203.pdf

Canadian Venous Thromboembolism Research Network (CanVECTOR). CanVECTOR Patient Partners Compensation Policy [Internet]. [cited 2022 Jul 19]. Available from: https://www.canvector.ca/platforms/patient-partners/canvector-pp-compensation-policy_v3-approved-march-2021.pdf

Richards DP, Cobey KD, Proulx L, Dawson S, de Wit M, Toupin-April K. Identifying potential barriers and solutions to patient partner compensation (payment) in research. Res Involv Engag. 2022;8(1):7.

Moher D. Guidelines for reporting health care research: advancing the clarity and transparency of scientific reporting. Can J Anaesth. 2009;56(2):96–101.

Moher D. Reporting research results: a moral obligation for all researchers. Can J Anaesth. 2007;54(5):331–5.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Lindsey Sikora (Health Sciences Research Librarian, University of Ottawa) for her help in developing the search strategies.

Funding

This study is supported by the Ontario SPOR Support Unit. The funding body played no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

GF coordinated the systematic review process, wrote the systematic review protocol, completed the PROSPERO registration, conducted the literature search, screened studies for eligibility, extracted data, analysed data and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. MML developed the initial idea for the study and supervised systematic review conduct. TS screened studies for eligibility and extracted data. SGN contributed to study design and analysed the data. MS contributed to study design and data interpretation. DS contributed to study design. FA screened studies for eligibility. DAF developed the initial idea for the study and supervised systematic review conduct. DAF and MML are the study guarantors and corresponding authors that contributed equally to this study. All authors reviewed, edited and approved the final version of the manuscript. All authors had full access to all the data in the study, and the corresponding authors had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication. The corresponding author attests that all listed authors meet authorship criteria and that no others meeting the criteria have been omitted.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1: PRISMA checklist

Section and Topic | Item # | Checklist item | Location where item is reported |

|---|---|---|---|

Title | |||

Title | 1 | Identify the report as a systematic review | 1 |

Abstract | |||

Abstract | 2 | See the PRISMA 2020 for Abstracts checklist | 3 |

Introduction | |||

Rationale | 3 | Describe the rationale for the review in the context of existing knowledge | 4 |

Objectives | 4 | Provide an explicit statement of the objective(s) or question(s) the review addresses | 4–5 |

Methods | |||

Eligibility criteria | 5 | Specify the inclusion and exclusion criteria for the review and how studies were grouped for the syntheses | 5, 6, 29 |

Information sources | 6 | Specify all databases, registers, websites, organisations, reference lists and other sources searched or consulted to identify studies. Specify the date when each source was last searched or consulted | 6 |

Search strategy | 7 | Present the full search strategies for all databases, registers and websites, including any filters and limits used | 6 |

Selection process | 8 | Specify the methods used to decide whether a study met the inclusion criteria of the review, including how many reviewers screened each record and each report retrieved, whether they worked independently, and if applicable, details of automation tools used in the process | 6 |

Data collection process | 9 | Specify the methods used to collect data from reports, including how many reviewers collected data from each report, whether they worked independently, any processes for obtaining or confirming data from study investigators, and if applicable, details of automation tools used in the process | 7 |

Data items | 10a | List and define all outcomes for which data were sought. Specify whether all results that were compatible with each outcome domain in each study were sought (e.g. for all measures, time points, analyses), and if not, the methods used to decide which results to collect | 7, 30 |

10b | List and define all other variables for which data were sought (e.g. participant and intervention characteristics, funding sources). Describe any assumptions made about any missing or unclear information | 7, 30 | |

Study risk of bias assessment | 11 | Specify the methods used to assess risk of bias in the included studies, including details of the tool(s) used, how many reviewers assessed each study and whether they worked independently, and if applicable, details of automation tools used in the process | 7 |

Effect measures | 12 | Specify for each outcome the effect measure(s) (e.g. risk ratio, mean difference) used in the synthesis or presentation of results | N/A |

Synthesis methods | 13a | Describe the processes used to decide which studies were eligible for each synthesis (e.g. tabulating the study intervention characteristics and comparing against the planned groups for each synthesis (item #5)) | 7, 8 |

13b | Describe any methods required to prepare the data for presentation or synthesis, such as handling of missing summary statistics, or data conversions | 7,8 | |

13c | Describe any methods used to tabulate or visually display results of individual studies and syntheses | 7, 8 | |

13d | Describe any methods used to synthesize results and provide a rationale for the choice(s). If meta-analysis was performed, describe the model(s), method(s) to identify the presence and extent of statistical heterogeneity, and software package(s) used | 7, 8 | |

13e | Describe any methods used to explore possible causes of heterogeneity among study results (e.g. subgroup analysis, meta-regression) | N/A | |

13f | Describe any sensitivity analyses conducted to assess robustness of the synthesized results | N/A | |

Reporting bias assessment | 14 | Describe any methods used to assess risk of bias due to missing results in a synthesis (arising from reporting biases) | N/A |

Certainty assessment | 15 | Describe any methods used to assess certainty (or confidence) in the body of evidence for an outcome | N/A |

Results | |||

Study selection | 16a | Describe the results of the search and selection process, from the number of records identified in the search to the number of studies included in the review, ideally using a flow diagram | 9 |

16b | Cite studies that might appear to meet the inclusion criteria, but which were excluded, and explain why they were excluded | 9, 31–47 | |

Study characteristics | 17 | Cite each included study and present its characteristics | 9, 31–47 |

Risk of bias in studies | 18 | Present assessments of risk of bias for each included study | N/A |

Results of individual studies | 19 | For all outcomes, present, for each study: (a) summary statistics for each group (where appropriate) and (b) an effect estimate and its precision (e.g. confidence/credible interval), ideally using structured tables or plots | 9–12, 19–23 |

Results of syntheses | 20a | For each synthesis, briefly summarise the characteristics and risk of bias among contributing studies | 9–12, 19–23 |

20b | Present results of all statistical syntheses conducted. If meta-analysis was done, present for each the summary estimate and its precision (e.g. confidence/credible interval) and measures of statistical heterogeneity. If comparing groups, describe the direction of the effect | 9–12, 19–23 | |

20c | Present results of all investigations of possible causes of heterogeneity among study results | N/A | |

20d | Present results of all sensitivity analyses conducted to assess the robustness of the synthesized results | N/A | |

Reporting biases | 21 | Present assessments of risk of bias due to missing results (arising from reporting biases) for each synthesis assessed | N/A |

Certainty of evidence | 22 | Present assessments of certainty (or confidence) in the body of evidence for each outcome assessed | N/A |

Discussion | |||

Discussion | 23a | Provide a general interpretation of the results in the context of other evidence | 12–13 |

23b | Discuss any limitations of the evidence included in the review | 13 | |

23c | Discuss any limitations of the review processes used | 13 | |

23d | Discuss implications of the results for practice, policy, and future research | 14–15 | |

Other information | |||

Registration and protocol | 24a | Provide registration information for the review, including register name and registration number, or state that the review was not registered | 5 |

24b | Indicate where the review protocol can be accessed, or state that a protocol was not prepared | 5 | |

24c | Describe and explain any amendments to information provided at registration or in the protocol | N/A | |

Support | 25 | Describe sources of financial or non-financial support for the review, and the role of the funders or sponsors in the review | 14 |

Competing interests | 26 | Declare any competing interests of review authors | 14 |

Availability of data, code and other materials | 27 | Report which of the following are publicly available and where they can be found: template data collection forms; data extracted from included studies; data used for all analyses; analytic code; any other materials used in the review | 14 |

Appendix 2: GRIPP II short form reporting checklist

Section and topic | Item |

|---|---|

1: Aim | Conduct a systematic review to assess the current landscape of reporting patient partner financial compensation and identifying current compensation practices. To partner with a patient partner throughout the development and conduct of the systematic review |

2: Methods | One patient partner (MS) was recruited to join the research team through personal referral. MS was involved in developing the protocol, defining compensation terms, identifying data items for extraction, analyzing systematic review results and contributed to edits of this paper. MS attended virtual team meetings and continued to meet with GF monthly. MS was offered financial compensation and co-authorship in recognition of her contributions to the research project |

3: Results | Patient engagement contributed to the study in several ways including: Informing the project proposal with the patient partner experience: MS is well integrated in the patient engagement field and has a wealth of experience being a patient partner for several organizations. MS has experience with various methods of compensation, barriers to financial compensation and the different perspectives that patient partners have on financial compensation Co-developed definitions for non-financial and financial compensation Categorizing methods of compensation as reimbursement, financial or non-financial compensation Identified opportunities to present the systematic review proposal and findings to larger panels of patient partners |

4: Discussion | Overall, patient engagement was successful in informing review development and conduct. Additionally, the research team learned a lot about the patient partner experience with financial compensation and institutions are recognizing patient partners for their expertise through discussions with MS about her unique experiences. It was helpful that MS was familiar with most team members before joining the research team and that members of the team had experience with patient engagement The systematic review was conducted within a year. At the beginning of the project, we co-developed a timeline and budget to reflect the number of hours that MS devoted to the project. In the future, we will refer back to this timeline at the mid-term mark to ensure that the number of hours budgeted for were accurate |

5: Reflections | Engagement was embedded within the research project and MS was a member of the research team. MS connected the research team with groups of patient partners who were interested in the systematic review findings. In turn, these connections yielded opportunities to connect with patient groups and disseminate review findings to an important stakeholder group. This would not have been possible without MS |

Appendix 3: Data extraction items

Data item | |

|---|---|

1. Corresponding author name, e-mail address, country of residence, and institutional affiliation at time of publication | |

2. Publication title | |

3. Year of publication | |

4. Journal/Source of publication | |

5. Funding details (e.g. source of funding, whether funding was received specifically to support patient engagement) | |

6. Type of stakeholder engaged (e.g. patients, caregivers, community member etc.) | |

7. Number of patient partners engaged | |

8. Length of engagement (i.e. whether patient partners were engaged once or multiple times throughout the project) | |

9. Research element where patient partners contributed (e.g. funding, priority-setting, governance, study design, data collection, data analysis, dissemination, ethics approval etc.) [2] | |

10. Level of patient partner engagement (as defined by Involve (33)) | |

11. Non-financial compensation offered to patient partners (e.g. co-authorship, gifts, refreshments etc.) | |

12. Did authors report on offering financial compensation to patient partners (patient partners need not accept)? (Yes or No) | |

13. Where are details of financial compensation reported in the manuscript? (e.g. methods, results, discussion) | |

(a) Type of financial compensation (e.g. honoraria, salary, cash etc.) | |

(b) Amount (rate and total) | |

(c) Payment frequency (e.g. bi-weekly, one-payment etc.) | |

(d) Reported guidelines or policies used to guide financial compensation | |

14. Stated reason for financially compensating patient partners or stated reason for not financially compensating patient partners | |

15. Reported benefits and challenges to financially compensating patient partners | |

16. Reported barriers and enablers to financially compensating patient partners |

Appendix 4: Included studies (n = 316)

-

1.

Zoellner, J. M. et al. Advancing engagement and capacity for rural cancer control: a mixed-methods case study of a Community-Academic Advisory Board in the Appalachia region of Southwest Virginia. Research Involvement and Engagement 7, (2021).

-

2.

Yu, R., Hanley, B., Denegri, S., Ahmed, J. & McNally, N. J. Evaluation of a patient and public involvement training programme for researchers at a large biomedical research centre in the UK. BMJ Open 11, (2021).

-

3.

Young, R. et al. Using nominal group technique to advance power assisted exercise equipment for people with stroke. Research Involvement and Engagement 7, (2021).

-

4.

Young, A. et al. The lived experience and legacy of pragmatics for deaf and hard of hearing children. Pediatrics 146, (2020).

-

5.

Woodford, J., Farrand, P., Hagström, J., Hedenmalm, L. & von Essen, L. Internet-administered cognitive behavioral therapy for common mental health difficulties in parents of children treated for cancer: Intervention development and description study. JMIR Formative Research 5, (2021).

-

6.

Williams, M. A. et al. Active treatment for idiopathic adolescent scoliosis (ACTIvATeS): A feasibility study. Health Technology Assessment 19, (2015).

-

7.

White, K. et al. Chronic Headache Education and Self-management Study (CHESS) - A mixed method feasibility study to inform the design of a randomised controlled trial. BMC Medical Research Methodology 19, (2019).

-

8.

Warner, G., Baghdasaryan, Z., Osman, F., Lampa, E. & Sarkadi, A. ‘I felt like a human being’—An exploratory, multi-method study of refugee involvement in the development of mental health intervention research. Health Expectations 24, 30–39 (2021).

-

9.

von Scheven, E., Nahal, B. K., Cohen, I. C., Kelekian, R. & Franck, L. S. Research Questions that Matter to Us: priorities of young people with chronic illnesses and their caregivers. Pediatric Research 89, 1659–1663 (2021).

-

10.

Vogsen, M., Geneser, S., Rasmussen, M. L., Hørder, M. & Hildebrandt, M. G. Learning from patient involvement in a clinical study analyzing PET/CT in women with advanced breast cancer. Research Involvement and Engagement 6, (2020).

-

11.

Vat, L. E. et al. Giving patients a voice: A participatory evaluation of patient engagement in Newfoundland and Labrador Health Research. Research Involvement and Engagement 6, (2020).

-

12.

Vanderhout, S. M. et al. Patient and family engagement in the development of core outcome sets for two rare chronic diseases in children. Research Involvement and Engagement 7, (2021).

-

13.

Van Schelven, F., Van Der Meulen, E., Kroeze, N., Ketelaar, M. & Boeije, H. Patient and public involvement of young people with a chronic condition: Lessons learned and practical tips from a large participatory program. Research Involvement and Engagement 6, (2020).

-

14.

van Rooijen, M. et al. How to foster successful implementation of a patient reported experience measurement in the disability sector: an example of developing strategies in co-creation. Research Involvement and Engagement 7, (2021).

-

15.

van Beinum, A., Talbot, H., Hornby, L., Fortin, M. C. & Dhanani, S. Engaging family partners in deceased organ donation research—a reflection on one team’s experience. Canadian Journal of Anesthesia 66, 406–413 (2019).

-

16.

Udayaraj, U. P. et al. Establishing a tele-clinic service for kidney transplant recipients through a patient-codesigned quality improvement project. BMJ Open Quality 8, (2019).

-

17.

Turner, G., Aiyegbusi, O. L., Price, G., Skrybant, M. & Calvert, M. Moving beyond project-specific patient and public involvement in research. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine 113, 16–23 (2020).

-

18.

Tsang, V. W. L., Fletcher, S., Thompson, C. & Smith, S. A novel way to engage youth in research: evaluation of a participatory health research project by the international children’s advisory network youth council. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth 25, 676–686 (2020).

-

19.

Troya, M. I. et al. Patient and Public Involvement and Engagement in a doctoral research project exploring self-harm in older adults. Health Expectations 22, 617–631 (2019).

-

20.

Treiman, K. et al. Engaging Patient Advocates and Other Stakeholders to Design Measures of Patient-Centered Communication in Cancer Care. Patient 10, 93–103 (2017).

-

21.

Tomlinson, J., Medlinskiene, K., Cheong, V. L., Khan, S. & Fylan, B. Patient and public involvement in designing and conducting doctoral research: The whys and the hows. Research Involvement and Engagement 5, (2019).

-

22.

Toledo-Chávarri, A. et al. Co-design process of a virtual community of practice for the empowerment of people with ischemic heart disease. International Journal of Integrated Care 20, 1–13 (2020).

-

23.

Toledo-Chávarri, A. et al. Toward a Strategy to Involve Patients in Health Technology Assessment in Spain. International Journal of Technology Assessment in Health Care 35, 92–98 (2019).

-

24.

Tierney, E. et al. A critical analysis of the implementation of service user involvement in primary care research and health service development using normalization process theory. Health Expectations 19, 501–515 (2016).

-

25.

Thomas, M. et al. Patient preferences to value health outcomes in rheumatology clinical trials: Report from the OMERACT special interest group✰. Seminars in Arthritis and Rheumatism 51, 919–924 (2021).

-

26.

Thomas, K. S. et al. Randomised controlled trial of silk therapeutic garments for the management of atopic eczema in children: The CLOTHES trial. Health Technology Assessment 21, 1–259 (2017).

-

27.

Tchajkova, N., Ethans, K. & Smith, S. D. Inside the lived perspective of life after spinal cord injury: a qualitative study of the desire to live and not live, including with assisted dying. Spinal Cord 59, 485–492 (2021).

-

28.

Taylor, J. et al. Making the patient voice heard in a research consortium: experiences from an EU project (IMI-APPROACH). Research Involvement and Engagement 7, (2021).

-

29.

Tallantyre, E. C. et al. Achieving effective patient and public involvement in international clinical trials in neurology. NEUROLOGY-CLINICAL PRACTICE 10, 265–272.

-

30.

Synnot, A. J. et al. Consumer engagement critical to success in an Australian research project: Reflections from those involved. Australian Journal of Primary Health 24, 197–203 (2018).

-

31.

Swaithes, L. et al. Understanding the uptake of a clinical innovation for osteoarthritis in primary care: a qualitative study of knowledge mobilisation using the i-PARIHS framework. Implementation Science 15, (2020).

-

32.

Stocker, R., Brittain, K., Spilsbury, K. & Hanratty, B. Patient and public involvement in care home research: Reflections on the how and why of involving patient and public involvement partners in qualitative data analysis and interpretation. Health Expectations 24, 1349–1356 (2021).

-

33.

Staniszewska, S. et al. Developing a Framework for Public Involvement in Mathematical and Economic Modelling: Bringing New Dynamism to Vaccination Policy Recommendations. Patient 14, 435–445 (2021).

-

34.

Staniszewska, S., Denegri, S., Matthews, R. & Minogue, V. Reviewing progress in public involvement in NIHR research: Developing and implementing a new vision for the future. BMJ Open 8, (2018).

-

35.

Staniszewska, S. et al. GRIPP2 reporting checklists: Tools to improve reporting of patient and public involvement in research. Research Involvement and Engagement 3, (2017).

-

36.

Staniszewska, S. et al. Developing the evidence base of patient and public involvement in health and social care research: The case for measuring impact. International Journal of Consumer Studies 35, 628–632 (2011).

-

37.

Staats, K., Grov, E. K., Husebø, B. & Tranvåg, O. Framework for patient and informal caregiver participation in research (PAICPAIR): Part 1. Advances in Nursing Science 43, E58–E70 (2020).

-

38.

Sohy, D. et al. Outside in–inside out. Creating focus on the patient–a vaccine company perspective. Human Vaccines and Immunotherapeutics 14, 1509–1514 (2018).

-

39.

Snooks, H. A. et al. What are emergency ambulance services doing to meet the needs of people who call frequently? A national survey of current practice in the United Kingdom. BMC Emergency Medicine 19, (2019).

-

40.

Snape, D. et al. Exploring areas of consensus and conflict around values underpinning public involvement in health and social care research: A modified Delphi study. BMJ Open 4, (2014).

-

41.

Snape, D. et al. Exploring perceived barriers, drivers, impacts and the need for evaluation of public involvement in health and social care research: A modified Delphi study. BMJ Open 4, (2014).

-

42.

Smits, D. W., Van Meeteren, K., Klem, M., Alsem, M. & Ketelaar, M. Designing a tool to support patient and public involvement in research projects: The Involvement Matrix. Research Involvement and Engagement 6, (2020).

-

43.

Smith, H. et al. Defining and evaluating novel procedures for involving patients in core outcome set research: Creating a meaningful long list of candidate outcome domains. Research Involvement and Engagement 4, (2018).

-

44.

Smith, A. B. et al. Patient and public involvement in the design and conduct of a large, pragmatic observational trial to investigate recurrent, high-risk non–muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Cancer (2021).

-

45.

Slåtsveen, R. E., Wibe, T., Halvorsrud, L. & Lund, A. Needs-led research: a way of employing user involvement when devising research questions on the trust model in community home-based health care services in Norway. Research Involvement and Engagement 7, (2021).

-

46.

Skovlund, P. C. et al. The impact of patient involvement in research: a case study of the planning, conduct and dissemination of a clinical, controlled trial. Research Involvement and Engagement 6, (2020).

-

47.

Skivington, K. et al. Development of the framework. HEALTH TECHNOLOGY ASSESSMENT 25, 1-+.

-

48.

Shields, G. E., Brown, L., Wells, A., Capobianco, L. & Vass, C. Utilising Patient and Public Involvement in Stated Preference Research in Health: Learning from the Existing Literature and a Case Study. Patient 14, 399–412 (2021).

-

49.

Shaw, L. et al. An extended stroke rehabilitation service for people who have had a stroke: the EXTRAS RCT. HEALTH TECHNOLOGY ASSESSMENT 24, 1-+.

-

50.

Sellars, E., Pavarini, G., Michelson, D., Creswell, C. & Fazel, M. Young people’s advisory groups in health research: Scoping review and mapping of practices. Archives of Disease in Childhood 106, 698–704 (2021).

-

51.

Seljelid, B. et al. Content and system development of a digital patient-provider communication tool to support shared decision making in chronic health care: InvolveMe. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making 20, (2020).

-

52.

Sehlbach, C. et al. Perceptions of people with respiratory problems on physician performance evaluation-A qualitative study. HEALTH EXPECTATIONS 23, 247–255.

-

53.

Seeralan, T. et al. Patient involvement in developing a patient-targeted feedback intervention after depression screening in primary care within the randomized controlled trial GET.FEEDBACK.GP. Health Expectations 24, 95–112 (2021).

-

54.

Schulte, F. S. M., Chalifour, K., Eaton, G. & Garland, S. N. Quality of life among survivors of adolescent and young adult cancer in Canada: A Young Adults With Cancer in Their Prime (YACPRIME) study. Cancer 127, 1325–1333 (2021).

-

55.

Scholz, B. & Bevan, A. Toward more mindful reporting of patient and public involvement in healthcare. Research Involvement and Engagement 7, (2021).

-

56.

Schmidt, A. M., Schiøttz-Christensen, B., Foster, N. E., Laurberg, T. B. & Maribo, T. The effect of an integrated multidisciplinary rehabilitation programme alternating inpatient interventions with home-based activities for patients with chronic low back pain: a randomized controlled trial. Clinical Rehabilitation 34, 382–393 (2020).

-

57.

Schilling, I. et al. Patients’ and researchers’ experiences with a patient board for a clinical trial on urinary tract infections. Research Involvement and Engagement 5, (2019).

-

58.

Sass, R. et al. Patient, Caregiver, and Provider Perspectives on Challenges and Solutions to Individualization of Care in Hemodialysis: A Qualitative Study. Canadian Journal of Kidney Health and Disease 7, (2020).

-

59.

Santer, M. et al. Adding emollient bath additives to standard eczema management for children with eczema: The BATHE RCT. Health Technology Assessment 22, 1–116 (2018).

-

60.

Sangill, C., Buus, N., Hybholt, L. & Berring, L. L. Service user’s actual involvement in mental health research practices: A scoping review. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing 28, 798–815 (2019).

-

61.

Sale, J. E. M. et al. Perspectives of patients with depression and chronic pain about bone health after a fragility fracture: A qualitative study. Health Expectations (2021).

-

62.

Sabey, A. & Hardy, H. Views of newly-qualified GPs about their training and preparedness: Lessons for extended generalist training. British Journal of General Practice 65, e270–e277 (2015).

-

63.

Sabey, A. & Hardy, H. Prepared for commissioning? A qualitative study into the views of recently qualified GPs. Education for Primary Care 24, 314–320 (2013).

-

64.

Rushton, A. et al. Patient journey following lumbar spinal fusion surgery (FuJourn): A multicentre exploration of the immediate post-operative period using qualitative patient diaries. PLoS ONE 15, (2020).

-

65.

Romsland, G. I., Milosavljevic, K. L. & Andreassen, T. A. Facilitating non-tokenistic user involvement in research. Research Involvement and Engagement 5, (2019).

-

66.

Rodgers, H. et al. Robot-assisted training compared with an enhanced upper limb therapy programme and with usual care for upper limb functional limitation after stroke: The ratuls three-group RCT. Health Technology Assessment 24, 1–232 (2020).

-

67.

Roche, P. et al. Valuing All Voices: refining a trauma-informed, intersectional and critical reflexive framework for patient engagement in health research using a qualitative descriptive approach. Research Involvement and Engagement 6, (2020).

-

68.

Robler, S. K. et al. Hearing Norton Sound: community involvement in the design of a mixed methods community randomized trial in 15 Alaska Native communities. Research Involvement and Engagement 6, (2020).

-

69.

Richards, D. P. et al. Guidance on authorship with and acknowledgement of patient partners in patient-oriented research. Research Involvement and Engagement 6, (2020).

-

70.

Retzer, A. et al. Development of a core outcome set for use in community-based bipolar trials—A qualitative study and modified Delphi. PLoS ONE 15, (2020).

-

71.

Racine, E. et al. 'It just wasn’t going to be heard’: A mixed methods study to compare different ways of involving people with diabetes and health-care professionals in health intervention research. Health Expectations 23, 870–883 (2020).

-

72.

Puggaard, R. S. et al. Establishing research priorities related to osteoarthritis care via stakeholder input from patients. Danish Medical Journal 68, 1–8 (2021).

-

73.

Price, J., Rushton, A., Tyros, V. & Heneghan, N. R. Expert consensus on the important chronic non-specific neck pain motor control and segmental exercise and dosage variables: An international e-Delphi study. PLoS ONE 16, (2021).

-

74.

Price, A. et al. SMOOTH: Self-Management of Open Online Trials in Health analysis found improvements were needed for reporting methods of internet-based trials. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 105, 27–39 (2019).

-

75.

Price, A. et al. Frequency of reporting on patient and public involvement (PPI) in research studies published in a general medical journal: A descriptive study. BMJ Open 8, (2018).

-

76.

Price, A. et al. Mind the gap in clinical trials: A participatory action analysis with citizen collaborators. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice 23, 178–184 (2017).

-

77.

Price, A. et al. Patient and Public Involvement in research: A journey to co-production. Patient Education and Counseling (2021).

-

78.

Price, A. et al. Patient and public involvement in the design of clinical trials: An overview of systematic reviews. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice 24, 240–253 (2018).

-

79.

Poolman, M. et al. Carer administration of as-needed subcutaneous medication for breakthrough symptoms in people dying at home: The cariad feasibility rct. Health Technology Assessment 24, 1–149 (2020).

-

80.

Pomey, M. P. et al. Assessing and promoting partnership between patients and health-care professionals: Co-construction of the CADICEE tool for patients and their relatives. HEALTH EXPECTATIONS 24, 1230–1241.

-

81.

Pollock, A. et al. Development of the ACTIVE framework to describe stakeholder involvement in systematic reviews. Journal of Health Services Research and Policy 24, 245–255 (2019).

-

82.

Pollock, A. et al. Stakeholder involvement in systematic reviews: A scoping review. Systematic Reviews 7, (2018).

-

83.

Poland, F., Charlesworth, G., Leung, P. & Birt, L. Embedding patient and public involvement: Managing tacit and explicit expectations. Health Expectations 22, 1231–1239 (2019).

-

84.

Poitras, M. E. et al. Decisional needs assessment of patients with complex care needs in primary care. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice 26, 489–502 (2020).

-

85.

Ploetner, C. et al. Understanding and improving the experience of claiming social security for mental health problems in the west of Scotland: A participatory social welfare study. Journal of Community Psychology 48, 675–692 (2020).

-

86.

Pezaro, S., Pearce, G. & Bailey, E. Childbearing women’s experiences of midwives’ workplace distress: Patient and public involvement. British Journal of Midwifery 26, 659–669 (2018).

-

87.

Patchwood, E. et al. Organising Support for Carers of Stroke Survivors (OSCARSS): a cluster randomised controlled trial with economic evaluation. BMJ Open 11, (2021).

-

88.

Paskins, Z. et al. Quality and effectiveness of osteoporosis treatment decision aids: a systematic review and environmental scan. OSTEOPOROSIS INTERNATIONAL 31, 1837–1851.

-

89.

Parslow, R. M. et al. Development of a conceptual framework to underpin a health-related quality of life outcome measure in paediatric chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalopathy (CFS/ME): prioritisation through card ranking. Quality of Life Research 29, 1169–1181 (2020).

-

90.

Parr, J. et al. Parent-delivered interventions used at home to improve eating, drinking and swallowing in children with neurodisability: The feeds mixed-methods study. Health Technology Assessment 25, 1–208 (2021).

-

91.

Parkash, V. et al. Assessing public perception of a sand fly biting study on the pathway to a controlled human infection model for cutaneous leishmaniasis. Research Involvement and Engagement 7, (2021).

-

92.

Pandya-Wood, R., Barron, D. S. & Elliott, J. A framework for public involvement at the design stage of NHS health and social care research: Time to develop ethically conscious standards. Research Involvement and Engagement 3, (2017).

-

93.

Østerås, N. et al. Improving osteoarthritis management in primary healthcare: results from a quasi-experimental study. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders 22, (2021).

-

94.

Ogourtsova, T. et al. Patient engagement in an online coaching intervention for parents of children with suspected developmental delays. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology 63, 668–674 (2021).

-

95.

Odgers, H. L. et al. Research priority setting in childhood chronic disease: A systematic review. Archives of Disease in Childhood 103, 942–951 (2018).

-

96.