Abstract

Background

A growing interest has centered on digital storytelling in health research, described as a multi-media presentation of a story using technology. The use of digital storytelling in knowledge translation (KT) is emerging as technology advances in healthcare to address the challenging tasks of disseminating and transferring knowledge to key stakeholders. We conducted a scoping review of the literature available on the use of patient digital storytelling as a tool in KT interventions.

Methods

We followed by Arksey and O’Malley (Int J Soc Res Methodol 8(1):19–32, 2005), and Levac et al. (Implement Sci 5(1):69, 2010) recommended steps for scoping reviews. Search strategies were conducted for electronic databases (Medline, CINAHL, Web of Science, ProQuest dissertations and theses global, Clinicaltrials.gov and Psychinfo). The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR) was used to report the review process.

Results

Of 4656 citations retrieved, 114 full texts were reviewed, and twenty-one articles included in the review. Included studies were from nine countries and focused on an array of physical and mental health conditions. A broad range of interpretations of digital storytelling and a variety of KT interventions were identified. Digital storytelling was predominately defined as a story in multi-media form, presented as a video, for selective or public viewing and used as educational material for healthcare professionals, patients and families.

Conclusion

Using digital storytelling as a tool in KT interventions can contribute to shared decision-making in healthcare and increase awareness in patients’ health related experiences. Concerns centered on the accuracy and reliability of some of the information available online and the impact of digital storytelling on knowledge action and implementation.

Plain English summary

Digital storytelling is a multi-media presentation of a story, often in the form of a narrated video. The use of digital storytelling of patient experiences with healthcare has gained attention in recent years, as a tool for sharing and understanding information among patients, caregivers, healthcare professionals and policy makers. A summary of the findings reported in studies looking at digital storytelling as a way of sharing information in healthcare is needed.

We searched literature that included the use of digital storytelling of patients’ healthcare experiences as a means of sharing and translating information, also referred to as knowledge translation or knowledge mobilization. There were 21 studies found from nine countries that used digital stories to look at experiences related to different physical and mental health conditions. A broad range of interpretations of digital storytelling and a variety of knowledge translation approaches were identified. The most common use of patients’ digital stories was educational material for healthcare professionals and other patients.

Using digital storytelling to translate knowledge can contribute to patients, caregivers, healthcare professionals and policy makers sharing the best available evidence when faced with making a health decision. Digital storytelling can help us understand patients’ health related experiences. Further work is needed to test the accuracy and reliability of some online information and how to best measure the impact of digital storytelling on knowledge translation activities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Sharing stories of healthcare experiences has become an approach to gain insight into a person’s perspective about their healthcare interactions, rather than focusing solely on an illness or condition [1]. Stories are a powerful tool for acquiring knowledge from patients about patients [2, 3]. Typically, patients tell their stories to others in oral or written form. The exchange of narratives between a patient and physician, described as narrative medicine, has been recognized as a model of care [2, 4]. As technology advances, stories are created and shared digitally, as a form of dissemination to a larger audience. Narrative medicine focuses on individual relationships between the healthcare provider and others, namely patients, other healthcare professionals, and society [4]. Patient narratives, as part of narrative medicine, have been used in clinical research and practice as a source of information, used as a tool for communication, engagement, persuasion, and health behavior change [5]. The focus and content of the narratives may differ, depending on the purpose within the clinical or research context [5, 6]. For example, the narrative may be an emotional account of receiving a diagnosis for a serious illness or could be a patient’s step by step account of daily insulin injections. Furthermore, the approach used to deliver stories will affect the reception from the audience [7]. For instance, using plain text as compared to a multi-media video with music and animations will impact the audience differently.

Digital storytelling has been defined as an arts-based multi-media presentation of a story, often in the form of a video [7]. It is also an accessible way of engaging patients within research, acknowledging the experiential knowledge they have to offer and creating connections with others including other patients, advocacy groups, caregivers, healthcare professionals and policy makers [3, 8,9,10]. Although limited research has employed patient digital storytelling in healthcare, it has been used as an educational tool for nursing students [11], healthcare intervention for patients with dementia [12], form of patient advocacy [9, 13], and method for communicating among women with HIV [14]. A systematic review protocol has outlined plans to examine methodological and ethical implications of digital storytelling in health research [10]. In spite of storytelling having a variety of uses not only at the micro level but also at the macro (policy) and meso (organizational) levels in healthcare. While no one theoretical model for digital storytelling has been embraced, Shaffer and colleagues [5] propose a Narrative Immersion Model that attempts to address the gaps in the literature by understanding the effects of health narratives on knowledge, attitudes and behavior. This theoretical model considers how narratives evoke different responses from other methods of sharing information. Here, we consider digital storytelling as a form of narrative. As such, we recognize that not all digital stories are equal, and we need to determine the purpose of using digital storytelling within individual studies to better understand the process and outcome of the stories [6]. Determining how or why digital storytelling is used within research is important to understand the outcomes and impact of this tool to minimize the knowledge-to-action gap.

The use of digital storytelling is a compelling approach for knowledge translation (KT) in healthcare because of how extensive, engaging and immediate the impact stories become when made accessible online [10, 15, 16]. Disseminating research findings to target audiences such as consumers and stakeholders is a complex task [17]. Successful KT activities requires planning and consideration of the knowledge providers and target audiences to ensure update of knowledge [18]. The use of digital stories to disseminate findings has not been explored. We conducted a scoping review to retrieve, review, and synthesize the current literature available [19] on digital storytelling as a tool to support different KT interventions in healthcare.

Methods

Prior to conducting this scoping review, the review protocol was registered with Educational and Research Archives (ERA) (https://doi.org/10.7939/r3-ks11-ze31). The scoping review process followed the five stages proposed by Arksey and O’Malley [20] and Levac et al. [21]: (1) identifying the broad research question, (2) finding relevant studies, (3) study selection, (4) charting the data, and (5) collating, summarizing and reporting results. The optional sixth stage, consultation, was not included in this review. Recommendations outlined by Levac and colleagues [21] were closely followed throughout all stages of the review. To provide transparency of the process, we used the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR) [22].

Stage 1: identifying the research question

The population identified for this review included patients, caregivers, healthcare professionals and policy makers, the intervention was digital storytelling, and the outcome included KT tools. While several terms have been used to describe mobilizing knowledge into action, knowledge translation, knowledge transfer, implementation science and research utilization are frequently used terms [17, 23]. All study designs were included, while commentaries, editorials, conference abstracts, and letters or responses to letters were excluded. The specific research question was: How are patients’ stories using digital storytelling as a KT tool used to inform other patients, caregivers, healthcare professionals and policy makers about health-related topics? We wished to identify the key concepts and characteristics related to digital storytelling of patients’ stories for KT research in the available literature including grey literature and no restriction of study designs.

Stage 2: identifying relevant studies

A library health information specialist developed and implemented the search for six electronic databases (MEDLINE, CINAHL, Web of Science, ProQuest dissertations and theses global, Clinicaltrials.gov, and PsycINFO). We narrowed the search to include literature published within the past 10 years (2009–2019) to May 16, 2019 based on technological advancements and secular trends. Digital storytelling has only recently been identified as a tool in healthcare [7, 8], and therefore, this time frame would sufficiently capture the most relevant information. The search terms included digital storytelling, personal narratives, multimedia, health research, healthcare, patient experience, patient engagement, knowledge dissemination and translation, as well as related terms with truncations [See Additional file 1 for detailed search strategy]. Citations were restricted to English only. Restricting the search to English studies was based on findings from systematic research evidence that reported no empirical evidence of bias seen if papers were written in languages other than English [24]. Grey literature from non-peer reviewed sources were searched specifically through the database ProQuest dissertations and theses global and included on a case-by-case basis, based on relevance to the research question.

Abstracts had to include digital storytelling focusing on health-related patient experiences. The inclusion criteria were based on research question and aim to identify and review research of digital storytelling for KT as defined by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR): “a dynamic and iterative process that includes synthesis, dissemination, exchange and ethically-sound application of knowledge to improve the health, provide more effective health services and products and strengthen the health care system” [25]. Knowledge translation strategies were identified and categorized as: educational materials, knowledge exchange, mass media, and community outreach [18, 26, 27]. Specifically, we identified current literature which used digital storytelling as a KT tool targeting patients, caregivers, healthcare professionals and policy makers [11, 28, 29]. To ensure a comprehensive review, we included all studies that had a KT component using digital stories regardless of whether it was explicitly stated as part of the methodology.

Stage 3: study selection

Citations were uploaded to Covidence [30], which is web-based software platform that streamlines the production of systematic reviews. Duplicate records were identified and removed at this stage. Titles and abstracts were independently reviewed by 2 reviewers (EP, SR) with reported “strong” (kappa = 0.82) inter-rater reliability agreement [31, 32]. Disagreements in study selection were resolved by discussion between the 2 reviewers, and when necessary, through third-party adjudication (MF, CAJ) if the reviewers did not arrive at consensus. Full text screening of included abstracts and titles was then completed by the same 2 reviewers.

Stage 4: charting the data

Data were extracted from the first five studies independently by both reviewers using a standardized extraction form. The reviewers discussed their findings and found a high level of consistency in the data extracted from the studies. After explicitly clarifying each of the data extraction points, one reviewer (EP) then completed data extraction for the remaining sixteen studies. Data based on the population, digital storytelling, KT intervention and study characteristics were extracted and documented in a Microsoft excel spreadsheet.

Stage 5: collating, summarizing and reporting results

After data extraction, the results were collated and summarized to include study characteristics based on the research question. The descriptive table presented the year of publication and country of origin, the purpose of the study, as well as the study design, target population, the rationale for using digital storytelling and the type of KT intervention. Key findings were outlined in the reported results and then synthesized and mapped based on the type of digital storytelling used, and the type of KT intervention.

Results

Study characteristics

Of the 4667 citations retrieved, 11 duplicates were removed, and the remaining 4656 citations were reviewed for eligibility. Based on the criteria outlined in Table 1, twenty-one studies were included in the review (Fig. 1). The majority of excluded studies (n = 50) did not include a KT component. Several studies were excluded because they were not research studies (n = 9), did not include digital storytelling (n = 13), or did not include patients (n = 8). Citations that did not have an available full text were excluded because they were conference abstracts (n = 5) or the authors did not respond to our full text request (n = 2).

Source: Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PRISMA Group (2009). Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med 6(7): e1000097. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed1000097

PRISMA flow chart.

Studies were from nine countries including seven from USA [33,34,35,36,37,38,39], five from Canada [13, 40,41,42,43], three from the United Kingdom [9, 15, 44], and one each from Australia [45], Dubai [46], Sweden [16], Italy [47], Germany [48] and Taiwan [49]. Nine studies were qualitative methods [15, 16, 34, 36,37,38, 41, 43, 49], four used mixed methods [35, 39, 42, 48], three were media reviews [40, 46, 47], two narrative reviews [9, 13], two descriptive studies [33, 44] and one was a scoping review [45]. Three studies were published graduate dissertations [9, 37, 38], with one being a narrative review [9] and two using qualitative methods [37, 38].

Study populations included children and youth [41, 42, 47] adults [15, 16, 34,35,36,37,38, 40, 48, 49], and older adults [43] with six studies not specifying the target population [9, 13, 33, 44,45,46]. Health related topics included health promotion [37, 38], dementia [43], chronic pain [42], mental health [45], infertility [40], inflammatory bowel disorder [36], post-traumatic stress disorder [16], chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder [33], diabetes [34, 46], and cancer [15, 35, 41, 47,48,49]. Four studies did not focus on a specific health condition [9, 13, 39, 44] but referred broadly to patients in healthcare settings (Table 2).

Digital storytelling terminology

While the interpretation of what is digital storytelling varied within these studies, the majority defined digital storytelling as a story in multi-media form, presented as a video, for selective or public viewing [9, 13, 15, 34, 35, 37,38,39,40,41, 47]. Other studies referred to digital storytelling as an exchange of information and communication using technology, such as through online patient forums and websites [33, 36, 44, 48, 49]. The target audience for the digital stories varied to include patients, caregivers, healthcare professionals and policy makers. For this review, all the stories were based on the patients’ experiences from the patients’ perspectives, although in some cases they were created in collaboration with healthcare professionals and researchers [9, 15, 35, 39, 42, 43].

Several types of digital storytelling were found including: (a) personal multi-media patient stories with a KT component such as digital stories created with researchers and patients in a workshop [9, 13, 15, 34, 35, 37,38,39, 41], (b) multiple resources with embedded stories such as health-related websites with patient stories [9, 33, 44, 46, 48], (c) interactive storytelling such as blog postings within online communities to share stories and information [16, 36, 45, 49], (d) audio/visual presentations such as YouTube videos or published documentaries with recordings of patient stories [40, 43, 47], and (e) digital educational resource for parents based on collective patient experiences such as an e-book [42].

The purpose of the stories also varied within the different forms of digital storytelling; yet, the primary reason for using digital storytelling in several studies was to inform and exchange knowledge [15, 33, 35,36,37, 39, 41,42,43,44, 46, 48]. Some stories served multiple purposes and, in several cases, digital stories were effective in engaging, comforting and informing the target audiences [16, 36, 40, 49]. In studies where health promotion or policy change was an objective, the digital stories served to engage and persuade the general public including policy makers and other stakeholders [34, 37, 38]. Digital storytelling was used in an array of KT strategies, predominantly for educational purposes.

Knowledge translation

Most studies used several KT strategies, except for six studies that used digital stories solely for relaying professional/patient education material [13, 15, 39, 41, 46]. Overall, digital storytelling was mainly used as a KT tool for educational purposes (n = 17) to inform healthcare professionals, patients and caregivers [9, 13, 15, 16, 33,34,35, 37,38,39, 41,42,43,44,45,46, 48]. A few studies, focused on health promotion to educate the general public [34, 37, 38]. In addition, KT strategies included information dissemination through mass media (n = 8) where social media and websites were used as platforms for KT of the digital stories [33, 36, 40, 44, 45, 47, 49]. Ten interactive sites provided opportunities for knowledge exchange, primarily for patients [16, 33, 35, 36, 40, 44, 45, 47,48,49]; however, five studies of these studies had overlap with mass media which permitted public access [36, 40, 44, 47, 49]. Community outreach (n = 6) focused on health behavior change, health promotion, and policy changes [33,34,35, 37, 38, 43].

Several studies discussed the power of patients’ digital stories to improve knowledge acquisition by being more accessible and engaging [15, 41, 43, 44]. Digital stories were easily retrieved by other patients, caregivers, healthcare professionals and the public, to complement or enhance the technical data presented as statistics [37, 44, 47]. The digital stories offer a deeper understanding of the patients’ healthcare experiences, including interactions with healthcare professionals and receiving assessments, education and treatment [45]. The knowledge included in digital stories were often compelling and persuasive to engage the audience and promote information retention [15, 34, 41,42,43]. Through digital storytelling, patients can provide perspectives to key stakeholders that may not have been otherwise, considered [15, 41].

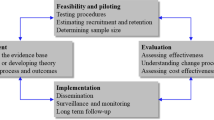

The digital storytelling types and KT interventions were mapped (see Fig. 2) to depict the different forms of digital storytelling used with different KT strategies. A majority of studies used digital stories as educational material for healthcare professionals, patients, caregivers and policy makers. The aims of these studies included training healthcare professionals [9, 13, 15, 35, 39, 41, 43, 45], analyzing the use of available social media and resources as educational tools for patients [16, 34, 45, 48], creating a database for healthcare researchers and patients to access [33, 44, 46], and using digital stories for public health education [34, 37, 38]. Mass media was used as a form of dissemination of information to a public audience, at times coinciding with digital stories as an educational resource. Patients have seized the opportunity to access this readily available information, and used social media platforms to interact with other patients and healthcare providers [36, 40, 49]. The use of interactive digital platforms for knowledge exchange may indicate a growing trend of acquiring knowledge through virtual communities, locally and internationally. These studies highlight patients’ desire to connect with other people who have similar experiences, appreciating the experiential knowledge they may offer [16, 33, 36, 49]. Another KT strategy, community outreach was used to examine health and social disparities, drawing on digital storytelling to bring communities together to promote awareness and to influence policy [34, 35, 37, 38].

Discussion

Findings from this review indicate that digital storytelling of patients’ health experiences is an emerging strategy for translating knowledge in healthcare. A large portion of the studies using digital storytelling for KT were published in the last five years (n = 16) which reflects the recent development of this approach for KT purposes. Digital storytelling used several different KT strategies for health research to enhance accessibility, education, and community building. Various forms of digital storytelling were discussed in our findings including an interactive exchange of stories, published videos, and patient stories embedded in websites about health conditions. In most cases, digital stories were part of educational resources for other patients, caregivers and healthcare professionals. Using a digital storytelling approach received a positive reaction by the target audiences as an engaging and powerful way of providing relevant and meaningful information.

Shared decision-making (SDM) and patient engagement have become an important elements of KT, in Canadian health research [50] and internationally [51]. In the past ten years, patients have been increasingly involved in KT research, as part of the CIHR initiative Strategies in Patient Oriented Research (SPOR), focused on patient involvement in health research [50]. An international organization, the International Patient Decision Aid Standards (IPDAS), consists of patients, clinicians, researchers, and policy makers, who have created and continue to update standards to ensure quality and effectiveness in the development and use of patient decision aids [51]. Patients want to be informed and aware of options available as well as be in a position to make choices based on reliable information [52, 53]. Patients may relay their stories of experience to contribute to the SDM process by providing other patients, caregivers, healthcare professionals and poly makers firsthand experiential knowledge. By sharing personal health experiences and hearing from other patients, the digital stories may help patients feel more confident to advocate for themselves. Health researchers recognize the need to offer opportunities for patients to be involved at various stages of research, to inform and support the decision making process [50, 51].

Healthcare professionals viewed digital storytelling as a viable KT tool in the form of interactive, knowledge exchange platforms for patients, caregivers and healthcare professionals to share knowledge and expertise. One concern of media-based digital storytelling is the quality or accuracy of information which is not typically monitored or substantiated by experts. Healthcare professionals have expressed concerns that patients do not have the expertise to provide reliable, evidence-based medical advice, creating a ripe opportunity to collaborate with patients and develop resources that are accessible and relatable. In spite of these concerns, patients appreciated the opportunity to share their stories with other patients and caregivers to provide support, insights and hope. Digital storytelling of patients’ experiences must include the voices of the patients while offering accurate and credible information. Drawing on resources from SPOR [50] and IPDAS [51] may provide patients and healthcare professionals with a guide to support collaboration and ensure reliability.

Our findings highlight the benefits of using digital storytelling in KT research including the use of the internet to improve access and engagement by patients and caregivers. Healthcare professionals were provided opportunities to gain a deeper understanding of their patients beyond their health conditions or diagnoses. For culturally diverse communities where health promotion and public health education may be more challenging, digital storytelling is a meaningful way to communicate and connect with community members. Inasmuch as no evidence-based framework for digital storytelling is endorsed within the literature, this review provided an overview of the extensive ways digital storytelling has been used. We also offered an outline of the different purposes and outcomes in the studies using digital storytelling as a KT tool, based on population and research questions. Synthesizing and mapping the evidence by type of digital storytelling, target population, and type of KT interventions offers a visual representation, summarizing the analysis in our scoping review.

Although methodological inclusivity allowed us to review diverse studies, limitations of this review included the inability to access some potentially relevant studies. Seven citations were excluded because the full texts were not available. The quality of the research of articles included was not assessed because of various types of research designs.

Measuring the impact of digital stories as a KT tool has not been investigated and is a gap in the available research. In many studies, the digital stories were publicly available online, but the impact on knowledge users was not evaluated. Those who accessed the digital stories, mainly patients and caregivers, reported that watching and hearing patient experiences was more appealing as compared to statistical or technical presentations. Evaluating the impact of digital storytelling in terms of knowledge acquisition, stakeholders’ understanding of patients’ experiences, and changes in behavior could provide rationale for supporting the use of digital storytelling with KT interventions in healthcare.

Implications

The use of technology, namely the media-based digital storytelling, allows patients and other stakeholders to access relevant information, but may lead to inaccurate or unsubstantiated material being distributed. Ensuring that appropriate healthcare professionals are aware of these resources and involved in knowledge dissemination could ensure the messages are corroborated and verified by trained specialists, while preserving the message being conveyed by patients.

This scoping review provides a synthesis of the digital storytelling literature used as a tool for KT interventions. Our findings highlight the benefits of using digital storytelling, including audience engagement and information retention, as well as facilitating patient involvement in the KT process. To maximize the potential of digital storytelling in KT activities, development of a framework would be helpful to guide the use of digital platforms and ensure consistency. Furthermore, it can support researchers and clinicians in making decisions of what types of digital storytelling to focus on, based on their desired outcomes and aims for KT.

Conclusions

The use of digital storytelling has emerged as a KT strategy in healthcare especially over the past five years; however, concerns with the accuracy and reliability of some of the available online information warrant further research. Evaluating the impact of digital stories in terms of knowledge transfer and implementation will provide valuable information as to the effectiveness of digital storytelling, particularly as different forms of digital storytelling emerge. There has been limited research on the extent of this impact, and how it may lead to changes in beliefs and/or behaviors warrants further investigation. Developing a framework to facilitate future research in this area would help patients, caregivers, health researchers, healthcare professionals and policy makers understand the types of digital storytelling and determine the most suitable option based on their KT goals.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- CHA/Ps:

-

Community health aid /professionals’

- CIHR:

-

Canadian Institutes of Health Research

- CINAHL:

-

The Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature

- Embase:

-

Bibliographic database for biomedical research

- ERA:

-

Educational and Research Archives

- IPDAS:

-

International Patient Decision Aid Standards

- KT:

-

Knowledge translation

- MEDLINE:

-

Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval System

- PRISMA-ScR:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for scoping reviews

- PsycINFO:

-

Psychological Information Database

- SDM:

-

Shared decision-making

- SPOR:

-

Strategies in patient oriented research

References

Frank AW. The wounded storyteller. 2nd ed. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 2013.

Charon R, Montello M. Stories matter: the role of narrative in medical ethics. New York: Routledge; 2002.

Gidman J. Listening to stories: valuing knowledge from patient experience. Nurse Educ Pract. 2013;13(3):192–6.

Charon R. The patient-physician relationship. Narrative medicine: a model for empathy, reflection, profession, and trust. JAMA. 2001;286(15):1897–902.

Shaffer VA, Focella ES, Hathaway A, Scherer LD, Zikmund-Fisher BJ. On the usefulness of narratives: an interdisciplinary review and theoretical model. Ann Behav Med. 2018;52(5):429–42.

Shaffer VA, Zikmund-Fisher BJ. All stories are not alike: a purpose-, content-, and valence-based taxonomy of patient narratives in decision aids. Med Decis Mak. 2013;33(1):4–13.

Lambert J, Hessler B. Digital storytelling: capturing lives, creating community. 5th ed. New York: Routledge; 2018.

Gubrium AC, Hill AL, Flicker S. A situated practice of ethics for participatory visual and digital methods in public health research and practice: a focus on digital storytelling. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(9):1606–14.

Hardy V: Telling tales: the development and impact of digital stories and digital storytelling in healthcare. 2016.

Rieger KL, West CH, Kenny A, Chooniedass R, Demczuk L, Mitchell KM, Chateau J, Scott SD. Digital storytelling as a method in health research: a systematic review protocol. Syst Rev. 2018;7(1):41.

Moreau KA, Eady K, Sikora L, Horsley T. Digital storytelling in health professions education: a systematic review. BMC Med Educ. 2018;18(1):208.

Stenhouse R, Tait J, Hardy P, Sumner T. Dangling conversations: reflections on the process of creating digital stories during a workshop with people with early-stage dementia. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2013;20(2):134–41.

Lal S, Donnelly C, Shin J. Digital storytelling: an innovative tool for practice, education, and research. Occup Ther Health Care. 2015;29(1):54–62.

Gray B, Young A, Blomfield T. Altered lives: assessing the effectiveness of digital storytelling as a form of communication design. Continuum. 2015;29(4):635–49.

Adams M, Robert G, Maben J. Exploring the legacies of filmed patient narratives: the interpretation and appropriation of patient films by health care staff. Qual Health Res. 2015;25(9):1241–50.

Salzmann-Erikson M, Hicdurmaz D. Use of social media among individuals who suffer from post-traumatic stress: a qualitative analysis of narratives. Qual Health Res. 2017;27(2):285–94.

Graham ID, Logan J, Harrison MB, Straus SE, Tetroe J, Caswell W, Robinson N. Lost in knowledge translation: time for a map? J Contin Educ Heal Prof. 2006;26(1):13–24.

Grimshaw JM, Eccles MP, Lavis JN, Hill SJ, Squires JE. Knowledge translation of research findings. Implement Sci. 2012;7(1):50.

Munn Z, Peters MDJ, Stern C, Tufanaru C, McArthur A, Aromataris E. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2018;18(1):143.

Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32.

Levac D, Colquhoun H, O’Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci. 2010;5(1):69.

Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, Moher D, Peters MDJ, Horsley T, Weeks L, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–73.

Straus SE, Tetroe J, Graham I. Defining knowledge translation. CMAJ. 2009;181(3–4):165–8.

Morrison A, Polisena J, Husereau D, Moulton K, Clark M, Fiander M, Mierzwinski-Urban M, Clifford T, Hutton B, Rabb D. The effect of English-language restriction on systematic review-based meta-analyses: a systematic review of empirical studies. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2012;28(2):138–44.

Knowledge Translation [https://cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/29418.html]

Jones CA, Roop SC, Pohar SL, Albrecht L, Scott SD. Translating knowledge in rehabilitation: systematic review. Phys Ther. 2015;95(4):663–77.

Scott SD, Albrecht L, O’Leary K, Ball GD, Hartling L, Hofmeyer A, Jones CA, Klassen TP, Kovacs Burns K, Newton AS, et al. Systematic review of knowledge translation strategies in the allied health professions. Implement Sci. 2012;7(1):70.

Gubrium A. Digital storytelling: an emergent method for health promotion research and practice. Health Promot Pract. 2009;10(2):186–91.

Park E, Owens H, Kaufman D, Liu L: Digital Storytelling and Dementia. In: Human Aspects of IT for the Aged Population Applications, Services and Contexts ITAP 2017. edn. Edited by Zhou J, Salvendy G: Springer International Publishing; 2017: 443–451.

Covidence systematic review software. In., www.covidence.org.edn. Melbourne, Australia: Veritas Health Innovation.

Belur J, Tompson L, Thornton A, Simon M. Interrater reliability in systematic review methodology: exploring variation in coder decision-making. Sociol Methods Res. 2018;50(2):837–65.

Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33(1):159–74.

Stellefson M, Paige SR, Alber JM, Stewart M. COPD360social online community: a social media review. Health Promot Pract. 2018;19(4):489–91.

Njeru JW, Patten CA, Hanza MM, Brockman TA, Ridgeway JL, Weis JA, Clark MM, Goodson M, Osman A, Porraz-Capetillo G, et al. Stories for change: development of a diabetes digital storytelling intervention for refugees and immigrants to Minnesota using qualitative methods. BMC Public Health. 2015;15(1):1311.

Cueva M, Kuhnley R, Lanier A, Dignan M, Revels L, Schoenberg NE, Cueva K. Promoting culturally respectful cancer education through digital storytelling. Int J Indig Health. 2016;11(1):34–49.

Frohlich DO. Inflammatory bowel disease patient leaders’ responsibility for disseminating health information online. Gastroenterol Nurs. 2019;42(1):29–40.

Halter AK: The power of storytelling: digital stories as a health promotion tool in the Yakima Valley. 2015.

Benson S. Exploring digital storytelling applications in the community. Washington: University of Washington; 2012.

Shapiro D, Tomasa L, Koff NA. Patients as teachers, medical students as filmmakers: the video slam, a pilot study. Acad Med. 2009;84(9):1235–43.

Kelly-Hedrick M, Grunberg PH, Brochu F, Zelkowitz P. “It’s totally okay to be sad, but never lose hope”: content analysis of infertility-related videos on Youtube in relation to viewer preferences. J Med Internet Res. 2018;20(5):e10199.

Laing CM, Moules NJ, Estefan A, Lang M. “Stories take your role away from you”: understanding the impact on health care professionals of viewing digital stories of pediatric and adolescent/young adult oncology patients. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 2017;34(4):261–71.

Reid K, Hartling L, Ali S, Le A, Norris A, Scott SD. Development and usability evaluation of an art and narrative-based knowledge translation tool for parents with a child with pediatric chronic pain: multi-method study. J Med Internet Res. 2017;19(12):e412.

Canning S, Phinney A. Data collection and knowledge translation through documentary film: they aren’t scary. Perspectives. 2015;38(1):6.

Ziebland S, Lavie-Ajayi M, Lucius-Hoene G. The role of the Internet for people with chronic pain: examples from the DIPEx International Project. Br J Pain. 2015;9(1):62–4.

De Vecchi N, Kenny A, Dickson-Swift V, Kidd S. How digital storytelling is used in mental health: a scoping review. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2016;25(3):183–93.

Marir F, Said H, Al-Obeidat F. Mining the web and literature to discover new knowledge about diabetes. Procedia Comput Sci. 2016;83:1256–61.

Clerici CA, Veneroni L, Bisogno G, Trapuzzano A, Ferrari A. Videos on rhabdomyosarcoma on YouTube: an example of the availability of information on pediatric tumors on the web. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2012;34(8):e329-331.

Engler J, Adami S, Adam Y, Keller B, Repke T, Fugemann H, Lucius-Hoene G, Muller-Nordhorn J, Holmberg C. Using others’ experiences Cancer patients’ expectations and navigation of a website providing narratives on prostate, breast and colorectal cancer. Patient Educ Counsel. 2016;99(8):1325–32.

Chiu YC, Hsieh YL. Communication online with fellow cancer patients: writing to be remembered, gain strength, and find survivors. J Health Psychol. 2013;18(12):1572–81.

Legare F, Stacey D, Forest PG, Coutu MF. Moving SDM forward in Canada: milestones, public involvement, and barriers that remain. Z Evid Fortbild Qual Gesundhwes. 2011;105(4):245–53.

Volk RJ, Llewellyn-Thomas H, Stacey D, Elwyn G. Ten years of the international patient decision aid standards collaboration: evolution of the core dimensions for assessing the quality of patient decision aids. BMC Med Inf Decis Mak. 2013;13:1–7.

Fraenkel L, McGraw S. What are the essential elements to enable patient participation in medical decision making? J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(5):614–9.

Stiggelbout AM, Van der Weijden T, De Wit MP, Frosch D, Legare F, Montori VM, Trevena L, Elwyn G. Shared decision making: really putting patients at the centre of healthcare. BMJ. 2012;344:e256.

Acknowledgements

We thank Sholeh Rehman, MSc. and Liz Dennett, MLIS for their assistance with this review.

Funding

EP was supported, in part, by a postdoctoral fellowship funded by Mitacs Accelerate, the Alberta Bone and Joint Health Institute (ABJHI) and the Faculty of Rehabilitation Medicine Postdoctoral Award at the University of Alberta.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

EP, MF, and CAJ contributed to the conception of this review. All authors contributed to its design. EP led and coordinated the development and writing of the paper. CAJ and MF participated throughout the development and writing of the review by contributing intellectual content and feedback on drafts of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

Medline Search Terms.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Park, E., Forhan, M. & Jones, C.A. The use of digital storytelling of patients’ stories as an approach to translating knowledge: a scoping review. Res Involv Engagem 7, 58 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40900-021-00305-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40900-021-00305-x