Abstract

Background

Chronic diseases like hypertension need comprehensive lifetime management. This study assessed clinical and patient-reported outcomes and compared them by treatment patterns and adherence at 6 months among uncontrolled hypertensive patients in Korea.

Methods

This prospective, observational study was conducted at 16 major hospitals where uncontrolled hypertensive patients receiving anti-hypertension medications (systolic blood pressure ≥ 140 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure ≥ 90 mmHg) were enrolled during 2015 to 2016 and studied for the following 6 months. A review of medical records was performed to collect data on treatment patterns to determine the presence of guideline-based practice (GBP). GBP was defined as: (1) maximize first medication before adding second or (2) add second medication before reaching maximum dose of first medication. Patient self-administered questionnaires were utilized to examine medication adherence, treatment satisfaction and quality of life (QoL).

Results

A total of 600 patients were included in the study. Overall, 23% of patients were treated based on GBP at 3 months, and the GBP rate increased to 61.4% at 6 months. At baseline and 6 months, 36.7 and 49.2% of patients, respectively, were medication adherent. The proportion of blood pressure-controlled patients reached 65.5% at 6 months. A higher blood pressure control rate was present in patients who were on GBP and also showed adherence than those on GBP, but not adherent, or non-GBP patients (76.8% vs. 70.9% vs. 54.2%, P < 0.001). The same outcomes were found for treatment satisfaction and QoL (P < 0.05).

Conclusions

This study demonstrated the importance of physicians’ compliance with GBP and patients’ adherence to hypertensive medications. GBP compliance and medication adherence should be taken into account when setting therapeutic strategies for better outcomes in uncontrolled hypertensive patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Hypertension is one of the major causes of death and the leading risk factor for cardiovascular disease and mortality worldwide [1]. However, achieving and maintaining blood pressure (BP) goals in hypertension has been challenging. About one-third of hypertensive patients are unaware of this condition or, if aware, do not undergo treatment, and target BP values are seldom achieved. This failure to control BP is associated with persistent elevated cardiovascular risk [2]. Most guidelines are based on evidence from multiple randomized clinical trials (RCTs) and recommend that the clinician should continue to assess BP and adjust the treatment regimen until goal BP is reached. If goal BP is not reached, guidelines recommend increasing the dose of the initial drug or adding a second drug from one of the recommended classes [2,3,4,5,6].

In real-world practice, most clinicians often care for patients with numerous comorbidities or other challenging issues, making BP control more difficult and this may be one of the reasons that clinicians do not follow guideline-based practice (GBP). In addition, almost half of patients discontinue treatment leading to poor BP control [7]. Poor adherence to medication can lead to cardiovascular morbidity and mortality [8, 9]. It has been established that medication adherence and BP control to recommended goal lead to a decrease in hypertension-related morbidity and mortality in hypertensive patients resulting in satisfaction with care and improvement in health-related quality of life (QoL) [10,11,12].

This study aimed to assess treatment patterns and medication adherence and to compare clinical (BP control) and patient-reported outcomes (treatment satisfaction and QoL) by treatment patterns and medication adherence at 6 months among uncontrolled hypertensive patients.

Methods

Patients and study design

A non-interventional, prospective and observational study was conducted at 16 nationwide, tertiary hospitals. Study patients were enrolled during 2015 to 2016 and assessed for the following 6 months. Eligible patients were aged over 20 years with uncontrolled hypertension, determined by 2 to 3 repeated clinic BP measurements (systolic BP ≥140 mm/Hg or diastolic BP ≥90 mmHg) at the time of enrolment. Patients with resistant hypertension, secondary causes of hypertension, or those enrolled in another drug intervention study, were excluded. The total study period for each enrolled patient was 6 months and patients were assessed at their regular visit at 3 months and 6 months after receiving antihypertensive medications.

Data were collected through a review of medical records and face-to-face patient interviews. Demographic data included age, gender, smoking status, alcohol behavior, regular exercise, lipid lowering diet, and education level. BP was measured by the attending physician using a standardized protocol with a validated mercury sphygmomanometer and an appropriate cuff size for the arm circumference. Researchers reviewed electronic medical records for asymptomatic organ damage (albuminuria, left ventricular hypertrophy on electrocardiogram, retinopathy, and arterial stiffening) and hypertension-related underlying disease (renal disease, cerebrovascular disease, diabetes, peripheral arterial disease, heart failure, and coronary artery disease). Physicians prescribed antihypertensive medications at their discretion without the need to follow any regulations or protocols at each patient’s visit. Treatment patterns were used to examine whether physicians followed GBP, which was based on the Joint National Committee 8 guideline [6] and was defined if one of following criteria was met; (1) maximize the first medication before adding a second or (2) add a second medication before reaching the maximum dose of the first medication to control BP. All subjects gave informed consent and the study was conducted after approval from the institutional review board at each hospital.

Assessment of medication adherence and patient-reported outcomes

Among the various methods of assessing medication adherence, we evaluated adherence using the 8-item Morisky Medication Adherence Scale (MMAS-8) with three levels of adherence (high, medium, low) [13,14,15]. The Korean version of the MMAS-8 was used for data collection and licensure agreement with the survey provider, Donald E. Morisky (dmorisky@gmail.com), was obtained. After approval for its use, treatment satisfaction was assessed using the Korean version of the Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire for Medication, version 1.4 (TSQM 1.4), consisting of four domains (effectiveness, side effects, convenience, global satisfaction) [16]. TSQM 1.4 domain scores range from 0 to 100, with higher scores representing higher satisfaction in three of the domains (effectiveness, side effects, convenience) regarding patients’ antihypertensive medications. The “global satisfaction” domain was used to assess the overall level of satisfaction or dissatisfaction with medications. The Korean version of the EuroQoL-visual analog scale (EQ-VAS, Rotterdam, Netherlands) was used (with permission) to evaluate patient QoL regarding antihypertensive treatment. Patients were asked to indicate how good or bad their health state is and check the point on the scale numbered from 0 (worst) to 100 (best). MMAS-8 was assessed three times, at the recruitment visit and at both follow-up visits; TSQM 1.4 and EQ-VAS were assessed at the recruitment visit and at the end-of-study visit. Patients were categorized as (1) GBP and adherent group, (2) GBP and non-adherent group, and (3) non-GBP according to GBP status and medication adherent by MMAS-8.

Statistical analysis

This study compared clinical and patient-reported outcomes between GBP and non-GBP groups, and between adherent and non-adherent groups. For the description of patients’ characteristics, continuous variables were presented with basic statistics (the number of observations, means and standard deviations), whereas frequency and percentage (%) were reported for categorical variables. For two-group comparisons, the generalized estimating equation (GEE) method was performed to compare the rates of GBP and adherence and the BP control rate, at different observation periods. Likewise, the paired t-test was used to estimate differences in treatment satisfaction and QoL between baseline and 6-month follow-up. Three group comparisons were conducted with the chi-square test for BP control and with ANOVA and/or Kruskal-Wallis test for treatment satisfaction and QoL. Only patients who visited at each observational period and completed the survey were included in group comparisons. A multivariable logistic regression analysis was conducted for BP control while multivariable linear regression analyses were applied to treatment satisfaction and QoL. For the multivariable analyses, factors that were found to be present from univariate analysis with a significance level of 10% (P < 0.1), and clinically meaningful, were adjusted. SAS ver. 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) was used for all statistical analyses.

Results

Study subjects

Table 1 explains baseline characteristics of the study subjects. This study included a total of 600 uncontrolled hypertensive patients (mean age 58.6 ± 13.4 years, 55.7% male) (Table 1). The mean duration of hypertension from the first diagnosis was 7.4 ± 6.7 years and the mean duration of treatment for hypertension was 6.8 ± 6.7 years. One hundred and fifty patients (25%) had asymptomatic organ damage and 113 patients (18.8%) had hypertension-related underlying diseases (Table 1). Patient characteristics between GBP and non-GBP, and between adherent and non-adherent groups at 6 months are described in the Table S1.

Guideline-based practice, medication adherence and blood pressure control

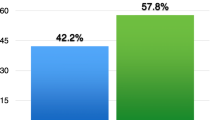

Overall, 23% of patients were treated based on GBP at 3 months, and the GBP rate increased to 61.4% at 6 months (P < 0.001 by GEE method) (Fig. 1). The percentage of adherent patients was 36.7% at baseline, increasing to 49.2% at 6 months (P < 0.001 by mixed model for repeated measurements). The proportion of BP-controlled patients increased during the study period, reaching 65.5% at 6 months (Table 2). In a multivariate analysis, BP control rate in the GBP and adherent group (odds ratio [OR] 2.65, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.58-4.42) and the GBP and non-adherent group (OR 1.67, 95% CI 1.02-2.76) was higher than in the non-GBP group (Table 3).

Guideline-based practice and medication adherence. a)Guideline-based practice (GBP) was based on the JNC 8 guidelines and defined as systolic BP (SBP) ≥140 mmHg or diastolic BP (DBP) ≥90 mmHg and with the treatment strategies for antihypertensive drugs meeting one of the following: (1) maximize first medication before adding second, (2) add second medication before reaching the maximum dose of the first medication, or (3) start with two medication classes separately or as a fixed-dose combination. If BP was controlled (either SBP < 140 mmHg or DBP < 90 mmHg) at the next visit, GBP was determined as the same treatment strategies were implemented. b) Adherence was defined as patients showing high adherence according to Morisky Medication Adherence Scale-8 and moderate and low adherent patients were categorized as non-adherent [13,14,15]. c) Indicates that a comparison of 2 values showed a significant difference at P < 0.001. P-values for visit effect by generalized estimating equation method

Guideline-based practice, medication adherence and patient-reported outcomes

Better treatment satisfaction was observed in the GBP and adherent group compared with the GBP and non-adherent, or non-GBP patients, in all domains (all P < 0.05) (Table 4). Patients who were treated according to GBP and adherent to their antihypertensive medications had better QoL than in both other groups of patients (P = 0.030) (Table 4).

Discussion

This multicenter, prospective, observational study demonstrated that physicians’ compliance with GBP and patients’ good adherence to prescribed medications are important to improve BP control, treatment satisfaction, and QoL. Overall, the GBP rate increased during the 6-month study period. Physicians tended to follow GBP throughout the study period and more patients showed better adherence at the end-of-study visit than at baseline (36.7% vs. 49.2%). Both physicians’ and patients’ good compliance to the treatment of hypertension led to an increase in BP control at 6 months in patients with uncontrolled hypertension. The non-GBP group, in which physicians did not follow GBP, showed the lowest BP control rate at 6 months and this was even lower than in the GBP but non-adherent group (70.9% vs. 54.2%). This result highlights the unfavorable effects of physician inertia (i.e., lack of therapeutic action when the patient’s BP is not controlled) in the treatment of hypertension in real-world practice [2]. In addition to this physician inertia, poor adherence to medication is the most important cause of poor BP control [17, 18]. After 6 months and 1 year, more than one-third and about one-half of patients, respectively, may stop their initial treatment [19]. In our non-interventional, observational study, adherence increased from about one-third of patients at baseline up to almost one-half of all patients at 6 months, mainly due to the GBP effect.

Patients’ satisfaction with their treatment is highly associated with compliant medication use, thereby affecting the clinical effectiveness and efficiency of medical care. Treated hypertensive patients with low treatment satisfaction may be more likely to have lower adherence to antihypertensive medications. Low satisfaction with treatment may be an important barrier to achieving high rates of treatment adherence [11]. There are several ways to assess patients’ satisfaction with their treatment. In the current study, we used TSQM which provides information to compare various medications used to treat a particular illness on the three primary dimensions of treatment satisfaction (effectiveness, side effects, convenience), as well as patients’ overall rating of global satisfaction based on the relative importance of these primary dimensions to patients [16]. We found that patients who were treated according to GBP and also adherent to their antihypertensive medications (GBP and adherent group) not only had a higher BP control rate, but also higher satisfaction with their treatment and better QoL than the other two groups of patients in the study.

In real life, poor adherence to antihypertensive medication leads to cardiovascular events and mortality [8, 9, 20]. In other words, poor adherence to antihypertensive therapy correlates with a higher risk of cardiovascular events [19, 20]. In contrast, it has been shown that good adherence to antihypertensive medications has positive impacts on clinical and patient-reported outcomes including treatment satisfaction and QoL [10,11,12]. Based on evidence from multiple RCTs, recent hypertension guidelines and meta-analyses recommend more intensive BP control in adult hypertensive patients to reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality [21,22,23]. To improve outcomes for hypertensive patients, physicians are recommended to make every effort to follow GBP and to improve adherence to antihypertensive treatment and BP control. However, the majority of treated hypertensive patients are unlikely to achieve recommended BP targets in real life.

Despite the meaningful findings in real-world healthcare settings, this study has a couple of limitations. First, caution is needed regarding the generalizability of the study results since the study only involved major tertiary hospitals which inevitably excluded patients who usually visit local clinics. Therefore, a study including various types of hospitals needs to be conducted for more clarification. Second, there might have been reporting bias resulting from recall bias of the responders regarding the nature of data collection. Measuring medication adherence was based solely on patients’ self-report which may have mistakenly underestimated or overestimated adherence. Objective methodology for the assessment of medication adherence may more clearly explain actual adherence levels in hypertensive patients.

Conclusions

This study demonstrated the importance of physicians’ compliance with GBP and patients’ adherence to prescribed antihypertensive medications to improve BP control, treatment satisfaction, and QoL. GBP compliance and medication adherence should be taken into account when setting therapeutic strategies in order to lead to better outcomes in patients with hypertension.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

Abbreviations

- BP:

-

Blood pressure

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- EQ-VAS:

-

EuroQoL-visual analog scale

- GBP:

-

Guideline-based practice

- GEE:

-

Generalized estimating equation

- MMAS-8:

-

8-item Morisky Medication Adherence Scale

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- QoL:

-

Quality of life

- RCTs:

-

Randomized clinical trials

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- TSQM 1.4:

-

Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire for Medication, version 1.4

References

Rahimi K, Emdin CA, MacMahon S. The epidemiology of blood pressure and its worldwide management. Circ Res. 2015;116:925–36.

Mancia G, Fagard R, Narkiewicz K, Redón J, Zanchetti A, Böhm M, et al. 2013 ESH/ESC guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: the task force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). J Hypertens. 2013;31:1281–357.

Shin J, Park JB, Kim KI, Kim JH, Yang DH, Pyun WB, et al. Korean Society of Hypertension guidelines for the management of hypertension. Part II-treatments of hypertension. Clin Hypertens. 2015;21:2.

Lindholm LH, Carlberg B. The new Japanese Society of Hypertension guidelines for the management of hypertension (JSH 2014): a giant undertaking. Hypertens Res. 2014;37:391–2.

Weber MA, Schiffrin EL, White WB, Mann S, Lindholm LH, Kenerson JG, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of hypertension in the community a statement by the American Society of Hypertension and the International Society of Hypertension. J Hypertens. 2014;32:3–15.

James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, Cushman WC, Dennison-Himmelfarb C, Handler J, et al. 2014 evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: report from the panel members appointed to the eighth joint National Committee (JNC 8). JAMA. 2014;311:507–20.

Van Wijk BL, Klungel OH, Heerdink ER, de Boer A. Rate and determinants of 10-year persistence with antihypertensive drugs. J Hypertens. 2005;23:2101–7.

Kim HJ, Yoon SJ, Oh IH, Lim JH, Kim YA. Medication adherence and the occurrence of complications in patients with newly diagnosed hypertension. Korean Circ J. 2016;46:384–93.

Kim S, Shin DW, Yun JM, Hwang Y, Park SK, Ko YJ, et al. Medication adherence and the risk of cardiovascular mortality and hospitalization among patients with newly prescribed antihypertensive medications. Hypertension. 2016;67:506–12.

Simpson SH, Eurich DT, Majumdar SR, Padwal RS, Tsuyuki RT, Varney J, et al. A meta-analysis of the association between adherence to drug therapy and mortality. BMJ. 2006;333:15.

Zyoud SH, Al-Jabi SW, Sweileh WM, Morisky DE. Relationship of treatment satisfaction to medication adherence: findings from a cross-sectional survey among hypertensive patients in Palestine. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2013;11:191.

Trevisol DJ, Moreira LB, Kerkhoff A, Fuchs SC, Fuchs FD. Health-related quality of life and hypertension: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. J Hypertens. 2011;29:179–88.

Morisky DE, Ang A, Krousel-Wood M, Ward HJ. Predictive validity of a medication adherence measure in an outpatient setting. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2008;10:348–54.

Berlowitz DR, Foy CG, Kazis LE, Bolin LP, Conroy MB, Fitzpatrick P, et al. Effect of intensive blood-pressure treatment on patient-reported outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:733–44.

Bress AP, Bellows BK, King JB, Hess R, Beddhu S, Zhang Z, et al. Cost-effectiveness of intensive versus standard blood-pressure control. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:745–55.

Atkinson MJ, Sinha A, Hass SL, Colman SS, Kumar RN, Brod M, et al. Validation of a general measure of treatment satisfaction, the treatment satisfaction questionnaire for medication (TSQM), using a national panel study of chronic disease. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2004;2:12.

Corrao G, Zambon A, Parodi A, Poluzzi E, Baldi I, Merlino L, et al. Discontinuation of and changes in drug therapy for hypertension among newly-treated patients: a population-based study in Italy. J Hypertens. 2008;26:819–24.

Krousel-Wood M, Joyce C, Holt E, Muntner P, Webber LS, Morisky DE, et al. Predictors of decline in medication adherence: results from the cohort study of medication adherence among older adults. Hypertension. 2011;58:804–10.

Naderi SH, Bestwick JP, Wald DS. Adherence to drugs that prevent cardiovascular disease: meta-analysis on 376,162 patients. Am J Med. 2012;125:882–7.e1.

Corrao G, Parodi A, Nicotra F, Zambon A, Merlino L, Cesana G, et al. Better compliance to antihypertensive medications reduces cardiovascular risk. J Hypertens. 2011;29:610–8.

Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, Casey DE Jr, Collins KJ, Dennison Himmelfarb C, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association task force on clinical practice guidelines. Hypertension. 2018;71:1269–324.

Bundy JD, Li C, Stuchlik P, Bu X, Kelly TN, Mills KT, et al. Systolic blood pressure reduction and risk of cardiovascular disease and mortality: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. JAMA Cardiol. 2017;2:775–81.

Ettehad D, Emdin CA, Kiran A, Anderson SG, Callender T, Emberson J, et al. Blood pressure lowering for prevention of cardiovascular disease and death: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2016;387:957–67.

Acknowledgments

The MMAS-8 scale, content, name and trademarks are protected by US copyright and trademark laws. Permission for use of the scale and its coding is required. A license agreement is available from Donald E. Morisky, ScD, ScM, MSPH, 294 Lindura Ct., USA; dmorisky@gmail.com. Editorial assistance was provided by David P. Figgitt, PhD, ISMPP CMPP™, Content Ed Net, with funding from Viatris Korea.

Funding

This study was sponsored by Viatris Korea Ltd., Seoul, Korea.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CJK, JHC, and YJK had substantial contributions to the conception and design of this study. ISS, CJK, BSY, BJK, JWC, DIK, SHL, WHS, DWJ, TJC, DKK, SHL, CWN, JHS, UK, JJK, JBP were contributed to the acquisition of the data for this work. JL and JC analyzed the data for this work. ISS was a major contributor in writing the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved prior to study conduction from institutional review board of each participating hospital. Written consent was obtained from each participant before study participation. The name of institutions which approved this study and reference number in the parentheses were followed. Kyung Hee University Hospital at Gangdong (2014-09-030), Wonju Severance Christian Hospital, Yonsei University Health System (2014-09-0019), Kangbuk Samsung Hospital, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine (2014-10-020), Eulji General Hospital (2014-11-001), Inje University Haeundae Paik Hospital (129792-2014-113), Severance Hospital, Yonsei University College of Medicine (4-2014-0776), Korea University Ansan Hospital (AS14134), National Health Insurance Service Ilsan Hospital (2014-10-002), Kosin University Gospel Hospital (2014-10-136), Inje University Busan Paik Hospital (2014-09-0030), Dankook University Hospital (2014-11-001), Keimyung University Dongsan Hospital (DSMC 2014-10-015), Ajou University Hospital (AJIRB-MED-SUR-14-350), Yeungnam University Hospital (2014-11-001-001), Inje University Ilsan Paik Hospital (IB-2-1411-051), Seoul National University Hospital (1410-016-616).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests. Jin-Hye Cha who is a full-time employee of Viatris Korea Ltd. and was not involved in the data analysis and making the decision to publish.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Table S1.

Patient characteristics at 6 months.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Sohn, I.S., Kim, C.J., Yoo, BS. et al. Clinical impact of guideline-based practice and patients’ adherence in uncontrolled hypertension. Clin Hypertens 27, 26 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40885-021-00183-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40885-021-00183-1