Abstract

This study investigated the effectiveness and dynamics of peer feedback in online and offline learning environments, focusing on English as a Foreign Language (EFL) students’ affective engagement and its impact on learning outcomes. Utilizing an explanatory sequential mixed methods design, the research divided participants into groups that studied through Zoom and traditional classrooms over 12 weeks, analyzing their engagement with peer feedback. Data were gathered from Likert-scale and open-ended questionnaires, along with performance scores on key tasks, and analyzed using descriptive statistics, t-tests, linear regressions, and thematic analysis. The findings indicated that students valued peer feedback in both settings, with online learners showing higher engagement levels. However, this engagement did not translate into improved writing skills, highlighting the need for further research into other factors that could enhance EFL writing proficiency.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The significance of peer feedback in ESL/EFL writing courses within higher education has been well-documented (Waluyo & Panmei, 2024; Zhang et al., 2022), yet there remains a notable deficiency in research concerning students’ affective engagement—namely, their emotional and motivational involvement—in the process of both providing and receiving peer feedback across varied learning environments (Astrid et al., 2021). Despite the acknowledged important role of peer feedback in enhancing linguistic skills, such as improving writing quality, content depth, organization, and grammatical precision, as identified by researchers (e.g., Fan & Xu, 2020; Xu et al., 2023), the emotional and motivational dimensions of student interactions within these feedback processes have not been extensively explored (Apridayani & Waluyo, 2022). This oversight extends to both traditional classroom settings and digitally mediated environments, where technological integration varies extensively. While this collaborative learning approach has been shown to significantly foster self-awareness among students about their writing deficiencies and enhance their command of the target language (Hyland & Hyland, 2019), student perceptions towards the credibility and utility of peer feedback diverge, particularly concerning the comparative reliability of peer versus instructor feedback (Saeli & Cheng, 2021).

Recent advancements in technology have infused the peer feedback process with innovative tools and platforms, such as Grammarly for real-time writing assistance and Google Docs for collaborative editing (Thi et al., 2023; Rahayu et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2023; Wu et al., 2022). These developments, along with the adoption of online environments like Wikis (Al Abri, 2021) and WriteAbout (Pratiwi & Waluyo, 2023; Waluyo et al., 2023) for feedback activities, represent a significant evolution in how peer feedback is facilitated. Nonetheless, this technological integration also brings to the forefront the critical gap in our understanding of how students’ affective engagements with peer feedback differ across the spectrum of learning environments in higher education. The emotional and motivational components of engagement play a crucial role in the feedback process, potentially influencing its effectiveness in varying educational modalities. To address this knowledge gap, the present study adopts an explanatory sequential mixed methods research design, focusing on a university in Thailand to explore the nuanced dynamics of peer feedback engagement across different learning contexts. This approach aims to elucidate the affective experiences of EFL students in peer feedback scenarios and assess the unique contributions of these activities to learning outcomes in both online and offline settings.

In this study, the following research questions are addressed:

-

1.

To what extent do the affective engagements of EFL students in peer feedback vary across diverse learning environments?

-

2.

How do peer feedback activities differentially contribute to the learning outcomes of EFL students in various learning environments?

Literature review

Peer feedback in Foreign/L2 writing

Peer feedback, encompassing a variety of practices such as peer review, editing, critiquing, and evaluation, has emerged as a fundamental collaborative pedagogical tool aimed at augmenting writing skills among ESL/EFL students. Since its adoption in the late 1980s (Berg, 1999), this method has gained prominence for its hands-on, reciprocal learning advantages, facilitating students’ roles as both authors and critics. This dual engagement fosters not only the improvement of writing skills through constructive criticism and dialogue but also the development of critical thinking and analytical abilities. Hu (2005) and Nguyen (2021) further substantiate this, presenting peer feedback as a catalyst for enhancing students’ writing competencies through interactive and reflective participation in their peer’s textual productions. Furthermore, Min (2016)’s investigation into the skill development during peer review sessions among college freshmen advocates for an integrated approach that combines mastery modeling with explicit corrective feedback, suggesting that such methodologies can significantly contribute to the refinement of academic writing skills.

The benefits of peer feedback extend beyond the mere mechanical aspects of writing to embrace emotional and cognitive growth, underpinned by increased self-awareness, confidence, motivation, and the fostering of social skills such as communication, empathy, and the ability to construct meaningful interpersonal relationships. Tian and Zhou (2020)’s exploration into the nuances of online peer feedback amongst Chinese EFL learners calls for a deeper comprehension of its dynamic nature, emphasizing its role in promoting a supportive learning environment conducive to personal and academic development. The empirical evidence presented by Huisman et al. (2020) through a meta-analysis of 24 quantitative studies corroborates the efficacy of peer feedback, illustrating a significant enhancement in writing performance amongst participants who engaged in peer feedback processes compared to those who did not or only engaged in self-assessment. Echoing this, Saeli and Cheng (2021)’s research within an Iranian EFL context further validates the positive impact of peer feedback, noting marked improvements in the quality of student writing. This body of research collectively stresses the multifaceted benefits of peer feedback, highlighting its critical role in the holistic development of language learners.

Despite its widespread acclaim, the application and impact of peer feedback in offline learning environments exhibit considerable variability across different educational contexts. While Tian and Li (2018) and Fan and Xu (2020) identify a general enthusiasm for both giving and receiving feedback, nuances in preferences and perceived efficacy suggest that the impact of peer feedback is contingent upon specific contextual factors. This is further evidenced by the mixed outcomes observed in various studies, with Majid and Islam (2021) reporting limited learning gains in Pakistan—pointing towards the potential need for integrating peer feedback with teacher evaluations—and Loan (2017) and Nguyen (2018) documenting positive receptions to peer-teacher feedback models in Thailand. These divergent findings accentuate the necessity of tailoring peer feedback practices to align with the unique cultural, educational, and individual needs of learners. Consequently, while peer feedback undeniably plays a crucial role in enhancing ESL/EFL students’ writing skills and fostering cognitive and affective development, its effectiveness and reception are significantly influenced by the specific learning environment and contextual dynamics.

Students’ affective engagement in peer feedback in offline and online settings

The exploration of students’ affective engagement in peer feedback within foreign/L2 writing contexts highlights the significance of emotional and motivational dimensions that underlie the process of exchanging critiques among peers. This engagement encompasses a range of feelings, attitudes, and perceptions, critically shaping students’ interactions with feedback mechanisms. Research across offline ESL/EFL writing environments reveals a complex interplay of cognitive, affective, and behavioral engagements in influencing writing performance outcomes. An empirical investigation by Jin et al. (2022) involving 88 postgraduate students identified a crucial correlation between these forms of engagement and improved writing performance, highlighting the essential role of the perceived utility of feedback comments. In contrast, Meletiadou’s (2021) study among Greek Cypriot EFL learners observed favorable enhancements in writing, notably in aspects such as mechanics, organization, and language use, attributing these improvements to the affective responses elicited by peer feedback. Further broadening the perspective, Vuogan and Li’s (2023) meta-analysis quantitatively affirmed the comprehensive benefits of peer feedback in L2 writing, equating its efficacy with that of teacher feedback and self-revisions, thereby accentuating the pivotal influence of affective engagement in the peer feedback process. These recent studies collectively emphasizes the intricate relationship between affective engagement and academic outcomes, stressing the role of emotional and motivational factors in the effectiveness of peer feedback in language learning environments.

Nonetheless, Wu and Schunn (2020) critically address the difficulty inherent in distinguishing between low-quality, vague feedback and high-quality, constructive comments, a challenge that poses a risk to the overall efficacy of feedback processes. Adding depth to this discussion, Shi (2021) explores the multifaceted complexity of learner engagement with feedback, highlighting how contextual and individual factors, as well as the interplay among various dimensions of engagement, influence the feedback experience. Wang (2014) further complicates the narrative by examining shifts in students’ perceptions of peer feedback’s usefulness over time, noting the development of potential negative attitudes. These studies point out the dynamics of student engagement with peer feedback, drawing attention to the comprehensive and often complex interrelations between the quality of feedback and affective responses. Such insights not only underline the nature of peer feedback in educational settings but also call for a sophisticated and critical examination of the methodologies and contexts that inform our understanding of this pedagogical interaction, particularly with respect to the affective engagements that significantly shape learning outcomes.

In the context of online learning environments, the dynamics and outcomes of peer feedback exhibit notable variation, with the efficacy of feedback being closely linked to its specificity and constructiveness. Kerman et al. (2022) delineate a clear distinction between successful and unsuccessful students based on the nature of feedback received; successful students benefit from problem-solving and constructive feedback that precisely identifies issues, thereby fostering significant improvements in writing. This finding features the predictive power of descriptive and solution-oriented feedback on student writing enhancement. However, a prevalent challenge arises as most students tend to concentrate solely on immediate tasks, often overlooking the provision of forward-looking suggestions or feedforward, which Latifi et al. (2021) identify as crucial for collaborative learning activities. Moreover, the interpersonal aspect of feedback in online settings is highlighted by Ma (2020), who observes that EFL students exhibit a tendency towards supportive and constructive interactions, with the nature of peer critiques serving as a predictor for course outcomes. Dressler et al. (2019) further contribute to this discussion by noting a preference among students for revising feedback that addresses surface-level issues over deeper, content-related feedback, and a similar trend is observed in the utilization of teacher-provided feedback. Despite these challenges, Al Abri et al. (2021) and Rezai (2022) report a generally positive attitude among EFL students towards engaging in peer feedback activities online, suggesting an overarching appreciation for the role of peer interactions in the learning process. Collectively, these studies indicate the interplay between feedback quality, affective engagement, and learning outcomes in online educational settings.

Online peer feedback mechanisms serve a dual role in enhancing the educational experience for both the providers and recipients of feedback, fostering engagement through various cognitive processes while facilitating reflective and higher-order thinking. According to Van Popta et al. (2017), Pham et al. (2020), and Zhan et al. (2023), this engagement not only supports the cognitive development of learners but also nurtures critical self-reflection and analytical skills. Further research by Lv et al. (2021) and Sha et al. (2022) indicates that the efficacy of online feedback is contingent upon several factors, including the source of feedback, the nature of the task, and the context within which teaching and learning occur. Notably, anonymity in feedback provision has been shown to encourage more comprehensive and reflective responses, incorporating metacognitive elements that enrich the feedback process. While both asynchronous and synchronous feedback modalities are valued by EFL learners, Shang (2017) highlights a preference for the asynchronous mode, suggesting its better alignment with learners’ needs for flexibility and reflection. Zhan et al. (2022) advocate for the strategic design of online peer feedback systems that prioritize formative, constructive feedback to maximize learning outcomes. Sun and Zhang (2022) introduce the concept of translanguaging within online feedback, demonstrating its superiority over monolingual (English-only) feedback in initial rounds of second language writing enhancement. This bilingual approach not only facilitates deeper comprehension and engagement but also offers distinct advantages in supporting the multifaceted improvement of second language writing capabilities, thereby underlining the complex interdependencies between feedback modality, cognitive and affective engagement, and language learning outcomes in online environments.

Comparison between online and offline learning

The exploration of peer feedback across online and offline learning environments previously attracted extensive scholarly attention, yet direct comparisons focusing on student engagement in these distinct settings were notably limited. Jongsma et al. (2022) undertook a meta-analysis that illuminated this gap, discovering that online peer feedback significantly surpassed offline peer feedback in terms of effectiveness, evidenced by an effect size of 0.33. This advantage became particularly evident in assessments of competency outcomes over self-efficacy in abilities. Despite the general positive disposition towards online peer feedback among students, they also pinpointed several disadvantages. Research by Ciftci and Kocoglu (2012) and Farahani et al. (2019) demonstrated that engagement in both forms of feedback led to student improvement. However, those participating in online peer feedback not only showed superior performance but also developed more favorable views of the technology-mediated feedback process. Lee and Evans (2019) revealed that online peer feedback positively influenced students’ writing self-efficacy, enhancing their perception of the value of giving feedback, which, in turn, directly and indirectly through a mediation effect involving self-regulatory efficacy and apprehension, led to improved writing outcomes.

Further investigations into the relationship between peer feedback and writing outcomes showed that students who received online feedback exhibited higher writing quality, as indicated by better grades and acceptance scores, along with a statistically significant increase in critical and directive comments, though the number of editing comments did not change. Critical feedback was found to correlate positively with learning outcomes, as Novakovich (2016) noted, stressing the critical importance of feedback quality in promoting deeper engagement and extending task duration. Novakovich and Long (2013) also emphasized the significance of feedback quality in fostering student engagement. Yang (2016) explored how students modified and developed their academic knowledge through online peer feedback, identifying essential strategies such as using keywords as scaffolds for understanding main ideas, observing the writing processes of higher proficiency peers for knowledge transformation, and tackling writing issues by revising their work upon receiving feedback, a process termed as knowledge construction. This collection of studies not only highlighted the differential impact of online versus offline peer feedback but also detailed the intricate relationship between feedback modality, student engagement, and academic achievement for the present study.

Method

Research design

This study utilized an explanatory sequential mixed methods research design, allowing the researchers to collect and connect quantitative and qualitative data progressively throughout the course of one study period (Creswell & Clark, 2007). With the addition of qualitative findings’ insights, the design provides the opportunity to explore quantitative results in greater depth, (Ivankova et al., 2006). Hence, the present study employed the design to collect quantitative data, consisting of survey and score data, and qualitative data, which were students’ perspectives and reflections on their learning experience of participating in offline or online peer review feedback activities.

Context and participant

The study was conducted at an autonomous university located in southern Thailand, where foreign English language lecturers from diverse countries, including Indonesia, India, Bhutan, the USA, the UK, the Philippines, and others, taught general English courses to first and second-year students. Most of these lecturers had obtained certification from the UK Professional Standards Framework (UKPSF) from Advance Higher Education, United Kingdom, and had published in Scopus-indexed journals.

The recruitment of participants in this study employed the convenient sampling method, which was chosen due to its non-random nature, as it allowed researchers to select individuals easily accessible to them (Sedgwick, 2013). A total of sixty-one second-year students, with a gender distribution of 14.8% male and 85.2% female, all majoring in Medical Technology, were chosen from the School of Allied Health Sciences. Among these participants, there were nine males and fifty-two females, aged between 20 and 22 years old, with an average age of 20.72 years (SD = 0.686). Prior to commencing their English course, all students underwent a standardized university English proficiency test that was aligned with the Common European Framework of Reference (CEFR). The majority of students (60.7%) belonged to the category of basic English users, specifically at the A2 level, followed by B1 (32.8%), and A1 (6.6%).

Subsequently, the research participants were randomly divided into two distinct groups: an online feedback group and an offline feedback group. The online feedback group consisted of thirty students, comprising 16.7% males and 83.3% females, aged between 20 and 21 years old. In contrast, the offline feedback group encompassed thirty-one students, with a gender distribution of 12.9% males and 87.1% females, whose ages ranged from 20 to 22 years old. The online group engaged in fully synchronous online classes facilitated through the Zoom application, while the offline students followed the traditional in-class approach for their entire 12-week learning period. This division between online and offline modes of instruction serves as a crucial foundation for the subsequent investigation into the impact of feedback delivery methods on the participants’ language learning outcomes. The participants received neither credit nor monetary compensation. Additionally, all participants were engaged from the inception to the conclusion of the course.

Feedback design and procedure

Feedback design

Over a 12-week period, participants attended weekly 2-hour sessions focused on survey research writing, encompassing the creation of questionnaires and reports. The curriculum emphasized hypothesis generation and the application of survey tools for validation. Key coursework involved the development of a survey questionnaire and the composition of both short and extensive survey reports. Following each assignment, the teacher distributed two distinct feedback forms to facilitate a peer review process. The first form aimed at evaluating surveys against criteria such as purpose, question clarity, grammar, question types, and overall construction, while the second targeted survey reports, focusing on purpose, target demographic, methodology, findings, discussions, conclusions, and grammatical accuracy. Additionally, students assigned scores based on their assessments and provided comments, guided by a concise orientation on utilizing the feedback forms effectively. This orientation clarified each criterion and offered practical advice on making constructive comments, thus equipping students for insightful peer feedback. The feedback process was documented through the forms illustrated in Appendices 1 and 2, ensuring a structured and informative peer review experience. Foreign English lecturers at the institution developed these two forms in accordance with the course objectives and assessment purposes. They were exclusively utilized internally for the course and subsequently validated by English lecturers at the institution.

Feedback procedures

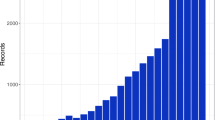

Two different procedures for giving peer review feedback were implemented. For the online peer feedback group, students were asked to post their assignments on the Facebook group created by the teacher since the first-class meeting. Then, the teacher assigned each student to read a specific student’s assignment and evaluate it using the peer review forms accordingly. After they finished their assessments, they would post their completed peer review form in the Reply button when his or her friend posted the assignment. Students conducted their peer reviews outside of class hours. These procedures were repeated for three assignments. It is important to note that students could see all their friends’ peer reviews posted in the Facebook group. Nonetheless, in the offline groups, students could only access their peers’ review results if they actively sought them out, and teachers actively encouraged them to share these results to facilitate collective learning among all students. Figure 1 is an example of the FB post for the peer review activities.

Meanwhile, for the offline feedback group, students were randomly paired and conducted their peer reviews using the forms accordingly. They were given 30 min of class time to assess and give feedback. When the time was over, each student gave his or her completed review forms to their friends accordingly. They were allowed to have a discussion if they had questions regarding their friends’ review results. In this group, other students could see all their friends’ review results, except the ones being evaluated. Students in both groups were randomly assigned to the peer that they were reviewing. All the students completed the same number of peers reviews.

It is crucial to recognize the variations in the time allocated for review tasks between the two groups. The offline feedback group had a strict 30-minute time limit during their in-class session, while the online feedback group enjoyed flexibility with no time constraints, completing their reviews outside of class. This distinction was made to align with the typical dynamics of English teaching and learning in higher education, where limited class hours necessitate time constraints for in-class activities, while online learners have more flexibility. Understanding these differences in review settings and allotted time is essential when interpreting the outcomes of this study, as they reflect the realities of various educational contexts. Below are samples of students’ peer review results (Fig. 2).

Instrument and measure

Likert-scale and open-ended survey questionnaires

The first instrument used in this study was a survey questionnaire. The survey consisted of three main sections. The first section collected information regarding students’ overall perceptions of the conducted peer feedback activities, students’ self-reported English proficiency and writing skills (3 items). Then, the second section measured students’ perceptions on the usefulness of reading and giving peer feedback based on research on peer review feedback (Latifi et al., 2021), as elaborated in the following paragraphs.

Reading peer feedback

This scale was intended to measure students’ perceptions of the usefulness of reading peer feedback. The scale included five items, such as “I found my classmates’ written comments useful.“; “My classmates’ written comments helped me enrich the content of my surveys and survey reports.“; “My classmates’ written comments helped me improve the organization of my surveys and survey reports.“; “My classmates’ written comments helped me improve the language (including grammar and vocabulary) of my surveys and survey reports.” “I benefited from my classmates’ written comments.” The responses range from 1 to 5, where “1” means “strongly disagree” and “5” means “strongly agree”. The Cronbach’s alpha was 0.961, indicating very high internal consistency.

Giving peer feedback

This scale was created to collect data on students’ experiences with and perceptions of giving peer feedback. In addition, the data on students’ preferences for giving feedback was also collected through this scale. The scale consisted of 7 items, such as “I like giving feedback to my friends’ surveys and survey reports.“, “When I give feedback to my friends’ surveys and survey reports, I try my best to help them improve their writings.“, “I always learn something after reading my friends’ surveys and survey reports.“, “I always hope that I can explain my feedback to my friends later in class.“, “Giving feedback to my friends’ surveys and survey reports helps me improve my grammar and vocabulary.“, “After giving feedback to my friends’ surveys and survey reports, I always know what I need to improve in my writings.” and “I prefer to be anonymous when giving feedback to my friends’ surveys and survey reports.” Similar to the first scale, the responses range from 1 to 5, where “1” = “strongly disagree” and “5” = “strongly agree”. The Cronbach’s alpha was 0.882, showing high internal consistency.

The last section required students to write short reflective responses on their learning experience from the peer review activities and their suggestions for future improvement. The responses were encouraged to be at least 50 words, either in English or Thai. The researchers translated all the Thai responses into English during the data analysis process. These self-reflective responses served as qualitative data in this study.

Task scores

Students’ scores from the three key assignments (developing a survey questionnaire, composing a short survey report, and composing an extended survey report) were collected as measures of learning outcomes. These were the scores from teachers. Each assignment was evaluated using specific assessment rubrics that students used for peer review activities (Figs. 1 and 2). Previous studies (e.g., Karim & Nassaji, 2020; Teng & Zhang, 2020) have utilized writing task scores as measures of writing learning outcomes, thereby suggesting the validity of employing them in the present study.

Data analysis

The collected data underwent an initial assessment for normality, following the skewness and kurtosis guideline of falling between − 2 and + 2 (George & Mallery, 2003). Since the results fell within this normal range, further analysis was conducted using parametric tests. Descriptive statistics, independent t-tests, and linear regressions were used to analyze the quantitative data, while the qualitative data were analyzed using a thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006; Braun et al., 2015). Thematic analysis is a methodical process used in qualitative research to identify, analyze, and report patterns within data. It begins with the researcher immersing themselves in the data to gain a comprehensive understanding. This is followed by systematically coding the data to highlight interesting features and organizing these codes into potential themes. These themes are then meticulously reviewed and refined to ensure they accurately represent the data, requiring sometimes to split, combine, or discard themes. The next step involves defining and naming the themes, focusing on clearly articulating the essence of each theme. The final stage is the production of a report that weaves together the analysis narrative, data extracts, and situates the findings within the broader research context and literature, offering a coherent and insightful exploration of the data. Figure 3 illustrates the thematic analysis process.

Results

Quantitative findings

Perceived usefulness of peer feedback, English proficiency and writing skills

The descriptive statistics showed that students in both online (M = 4.23, SD = 0.68) and offline groups (M = 3.90, SD = 0.79) perceived the peer feedback activities as useful and there was not statistically different on their perceived usefulness (t (2, 59) = 1.748, p = .086). Their self-reported English proficiency was at a good level (online: M = 3.90, SD = 0.68, offline: M = 3.45, SD = 0.72), but they believed their writing skill was at a moderate level (online: M = 3.37, SD = 0.77, offline: M = 3.26, SD = 0.68); nonetheless, there were no significant differences between the two groups in these criteria as presented in Table 1. These results demonstrate that both groups of students had equally positive perceptions of the usefulness of peer review and of their own self-perceived English proficiency levels and writing skills, allowing further statistical analyses for comparative purposes.

Engagements in peer feedback activities across learning environments

The first research question explored the differences of EFL students’ engagements in peer feedback activities across learning environments, focusing on the values of reading, and giving feedback. The results of independent t-tests unveiled that students involved online (M = 4.13, SD = 0.60) peer feedback activities had a higher appreciation of reading peer feedback that those engaged in offline (M = 3.77, SD = 0.72) feedback: t (2, 59) = 2.089, p = .04. The effect size was medium (Cohen’s d = (3.77–4.13) ⁄ 0.66 = 0.54). Similarly, online (M = 4.14, SD = 0.32) students also reported a higher appreciation of giving peer feedback than offline (M = 3.76, SD = 0.70) students: t (2, 59) = 2.715, p = .009. A medium effect size was also observed in the latter results (Cohen’s d = (3.76–4.14) ⁄ 0.54 = 0.70). Both online and offline students possessed high appreciation of reading and giving peer feedback in this study as indicated by the means in Table 2.

Differential contribution of peer feedback activities to the learning outcomes

The second research question examined the differential contribution of peer feedback activities to the learning outcomes of EFL students across different learning environments. The logic behind employing linear regression was to systematically assess the relationship between students’ engagement in peer feedback activities (specifically, reading and providing feedback) and their subsequent academic performance on writing tasks. Linear regression served as a statistical tool to determine whether students’ positive perceptions and active participation in peer feedback activities translated into measurable improvements in their writing abilities across different learning environments, including both online and offline settings. The construction of these models allowed for a precise examination of the impact of peer feedback activities on the learning outcomes. The data on students’ perceptions of reading and giving peer feedback were regressed on their 1st, 2nd, and final writing tasks. Surprisingly, the results revealed that despite their positivity in reading and giving peer feedback, none of those significantly (p > .05) contributed to their writing outcomes in both online and offline learning environment as measured by the three tasks, as presented in Table 3.

Qualitative findings

Students’ engagements in the online environment

The thematic analysis results of students’ responses on their online peer feedback engagements revealed four themes:

Theme 1: Improvement of writing skills

The participants expressed positive views on the activity, which they perceived as an opportunity to enhance their English proficiency, especially in writing. They appreciated receiving feedback on their tasks, which helped them identify and correct their grammatical errors and improve their explanatory skills. They also recognized the value of the activity for developing their report making skills, testing their understanding of data collection, and increasing their efficiency. The activity also enabled them to learn new things and broaden their perspectives.

“It is an excellent activity that promotes writing growth. The survey runs more smoothly when grammar is used correctly.” (S9)

“It aims to assess comprehension of data collection and report-writing skills. Receiving feedback from others makes me more conscious of my own errors and improves the efficiency of my work.” (S10)

Theme 2: Self and peer assessment

Students learned from peer review activities and applied their knowledge to their own writing. They recognized their own mistakes and appreciated different writing styles from their peers’ feedback. They also benefited from reviewing their friends’ works, as it helped them improve their grammar, vocabulary, and content. Moreover, they valued the mutual support and advice that peer review offered. The excerpts suggest that peer review was a useful and effective strategy for enhancing students’ writing skills.

“I am aware of my own mistakes, and I have observed a range of writing styles through peer assessments from friends.” (S12)

“I think it’s really valuable since when I’m analyzing my friends’ work, it also offers me a review of my grammatical and vocabulary material.” (S22)

Theme 3: Collaboration and exchange of ideas

Students highlight the benefits of peer feedback, such as learning from each other’s mistakes, exchanging opinions, improving the organization of information, and expressing their views on their own and others’ work. They also indicate that peer review activity fosters collaboration and mutual support among friends who can correct or complement each other’s work.

“I think it’s more of a social activity for friends to teach friends. We can communicate if there is a problem or if you wish to add more.” (S11)

“I believe it’s a worthwhile activity. I discussed with friends whether they were doing anything incorrectly or correctly in order to improve things and to assess if the task was done successfully or not.” (S24)

Theme 4: Language practice and development

Students appreciate the opportunity to exchange feedback and ideas with their peers, which they consider as a form of brainstorming. Additionally, they value the application of the knowledge gained from this course in real-life situations and the practice of using polite language and English grammar.

“In my perspective, peer review exercise is beneficial since it is likely a form of brainstorming, and two heads are better than one. Also, this can aid to improve writing faults and grammar.” (S15)

“A useful activity is peer review. It helps us to practice utilizing English more. Using nice terms to critique and criticize your friend’s works” (S25)

Students’ engagements in the offline environment

Students believe that peer feedback is helpful for improving one’s own writing and understanding of course material and they have positive attitudes towards peer feedback activities, finding them helpful and engaging. This theme is evident in comments such as:

“It aids in the recall of knowledge” (S12)

“Learn to write in English and try creating inquiries” (S27)

“That’s good because we can use what our friends say to develop” (S26)

Discussion

This study identified a lack of research specifically comparing students’ engagements in both online and offline learning environments in the EFL contexts. Thus, framed by an explanatory sequential mixed methods research design, it examined students’ engagements in different learning environments by focusing on the differences of EFL students’ engagements and the differential contribution of peer feedback activities to the learning outcomes. Three points worth discussing.

The usefulness of online and offline peer feedback activities

The results of this study are consistent with a considerable amount of existing research, providing strong evidence to support the agreement that peer feedback exercises are highly beneficial for students in both online and offline educational settings. These activities have been repeatedly documented in earlier research (Hu, 2005; Min, 2016; Nguyen, 2018, 2021; Tian & Li, 2018; Tian & Zhou, 2020; Loan, 2017) as factors that contribute to a variety of positive outcomes. The available research indicates that these tools play a role in improving students’ writing skills, supporting the acquisition of self- and peer-evaluation abilities, encouraging collaborative learning, facilitating the exchange of ideas, and fostering language proficiency and overall development.

The examination of students’ involvement with peer feedback aligns with the findings made by Fan and Xu (2020), providing insight into the varying effects of different forms of feedback. This study specifically emphasizes that the use of form-focused feedback resulted in increased levels of emotional, behavioral, and cognitive engagement. On the other hand, content-focused feedback led to relatively lower levels of cognitive and behavioral engagement. Nevertheless, our research also highlights the crucial viewpoint presented by Jin et al. (2022), which emphasizes the interconnection between the efficacy of peer feedback and the usefulness and applicability of the remarks given. This highlights the significant importance of the quality of comments in driving students’ advancement in writing skills.

Additionally, the findings from the quantitative study indicated a convergence in the perspectives of students belonging to both online and offline learning cohorts. The students unanimously regarded peer feedback activities as highly beneficial, with no statistically significant differences in their evaluations. It is noteworthy to mention that the students in question exhibited rather high levels of self-assessed English proficiency; however, they perceived their writing abilities to be of a moderate level. The similarities observed in the perceptions and self-assessments of both groups indicate that the advantages of peer review extend beyond the confines of the learning mode. The comprehensive examination of students’ perspectives and self-evaluations presented in this study contributes to a more nuanced comprehension of the broad-ranging benefits of peer feedback in various educational environments.

Online students are engaged more

The investigation of the involvement of English as a Foreign Language (EFL) students in peer feedback activities in various learning environments, with a specific emphasis on their perception of the value of reading and providing feedback, produced significant quantitative findings. The results of the t-tests indicated a statistically significant difference between students who participated in online peer feedback activities and those who engaged in offline peer feedback activities. In particular, students who engaged in online peer feedback activities demonstrated a notably greater level of appreciation for both the act of reading and the act of providing peer feedback in comparison to their peers who participated in offline activities. The significance of these distinctions should not be underestimated, as seen by the medium effect sizes. This indicates that online peer feedback activities may be more successful in including EFL students in the fundamental practice of peer feedback, which is a vital aspect of language acquisition.

Yet, it is crucial to stress that both students engaged in online and offline learning demonstrated considerable levels of value for peer evaluation. The shared characteristic highlighted in this context highlights the efficacy of both educational settings in facilitating active participation in peer feedback exercises, consistent with prior scholarly investigations (Ciftci & Kocoglu, 2012; Farahani et al., 2019; Pham et al., 2020; Van Popta et al., 2017; Vuogan & Li, 2023; Zhan et al., 2023). The aforementioned findings validate the notion that although online platforms may have some benefits in terms of peer feedback engagement, traditional offline settings continue to be favorable for conducting peer feedback activities. This offers educators a range of possibilities for incorporating peer feedback into their teaching practices.

Within the context of online learning, the study of students’ replies yielded four distinct themes that emerged prominently. Initially, the students articulated their perception that engaging in online peer evaluation activities offered a potential avenue for augmenting their English language ability, particularly in the domain of writing. The individuals expressed gratitude for the feedback they received regarding their jobs, as it aided them in recognizing and addressing grammatical faults while enhancing their ability to provide clear explanations. Furthermore, the individuals acknowledged the significance of engaging in these tasks as a means of refining their aptitude for generating reports, evaluating their comprehension of data gathering, and augmenting their general productivity. The participants also viewed the activities as a method of acquiring new knowledge and expanding their viewpoints.

The qualitative insights provided in this study serve to enhance the quantitative findings by providing a more comprehensive knowledge of the underlying mechanisms that contribute to student engagement and learning in online peer feedback activities. The qualitative data presented in this study are consistent with other scholarly works (Ma, 2020; Latifi et al., 2021; Waluyo & Bakoko, 2021; Wang et al., 2023), as they emphasize the beneficial effects of online peer feedback on the development of language proficiency and collaborative abilities. The findings of this study together highlight the various benefits of online peer feedback, stressing its ability to enhance both student engagement and significant learning outcomes.

No contribution to writing outcomes

The results of the quantitative analysis (Table 3) suggest that students’ perceptions of reading and giving peer feedback did not significantly contribute to their writing outcomes in both online and offline learning environments. These findings are unexpected given the positive effects of peer feedback on writing outcomes that have been reported in previous research (Jongsma et al., 2022; Novakovich, 2016; Novakovich & Long, 2013; Yang, 2016). One possible explanation for these results is that the quality of feedback provided by peers may not have been sufficient to impact students’ writing outcomes. Alternatively, other factors, such as the students’ level of English proficiency, motivation, or the type of feedback provided, may have influenced the relationship between peer feedback and writing outcomes. Students’ perceptions of the value of giving peer feedback boosted their writing self-efficacy directly and indirectly through a system including writing self-regulatory efficacy and apprehension, which might or might not lead to better writing results (Lee & Evans, 2019; Guo et al., 2023).

Implications

From the findings, there are three possible implications drawn:

-

1.

English teaching and learning

The findings of this study suggest that incorporating peer feedback activities in both online and offline learning environments can be an effective way to promote EFL students’ writing abilities, self and peer evaluation, cooperation and exchange of ideas, and language practice and growth. English teachers can use these findings to design and implement peer feedback activities in their classes to enhance their students’ writing skills and promote collaboration. Nevertheless, it is imperative to emphasize that students’ perceptions of the efficacy of peer feedback tend to diminish over time, even though this specific study does not explicitly mention it; however, teachers’ observations have noted this trend. Additionally, while an evaluation rubric can be applied to assess peers’ work, it’s noteworthy that Wang (2014) also documented instances of unfavorable impressions regarding peer feedback.

-

2.

Pedagogy in general

The study’s results indicate that online peer feedback activities may be more effective in engaging EFL students in the peer feedback process than offline peer feedback activities. Therefore, educators can consider integrating more online peer feedback activities in their teaching methods to enhance students’ engagement, interaction, and language learning. Additionally, teachers can use these findings to design more effective feedback techniques that encourage peer-to-peer collaboration and feedback that focus on form and content. Peer feedback assists students in becoming more aware of their writing errors and learning to use the target language effectively (Hyland & Hyland, 2019). However, students’ affective engagement with peer feedback was unfavorable in some situations because they perceived their teachers to be more reliable sources (Saeli & Cheng, 2021), but peer feedback can still be used as an effective supplementary aid to teacher feedback (Wu et al., 2022).

-

3.

Research development

This study provides insight into the importance of peer feedback in EFL learning and its effectiveness in both online and offline learning environments. Further research can explore the factors that affect the relationship between peer feedback and writing outcomes, such as the quality of feedback provided, students’ level of English proficiency, and motivation. Furthermore, future studies can also investigate the effectiveness of different types of feedback in promoting writing skills and language learning. It is, however, acknowledged that this study involved a small sample size and put more emphasis on quantitative research analysis. Thus, the findings may only be limited to the contexts that share similarities to the participants involved in this study.

Limitations

This research offers significant contributions to the understanding of how English as a Foreign Language (EFL) students engage with peer feedback in various educational settings. The study utilizes both quantitative and qualitative research methods to gather and analyze data. However, it is crucial to recognize specific constraints that could impact the applicability and understanding of our results. The sample size utilized in this study, although providing valuable insights, is somewhat small, which may pose limitations to the generalizability of our findings. There is a potential for sample bias to be present in this study, given the participants were selected only from specific courses or universities. It is worth noting that the students in this study participated voluntarily, which could suggest that they were inherently more motivated than the average student population. Being basic users of English (A2 levels), they might have limitations in providing qualitative responses compared to students with higher proficiency levels. This heightened motivation might have influenced their overall positive perception of the peer review process. The collection of self-reported data, which encompasses individuals’ perceptions of usefulness, English proficiency, and writing skills, may be influenced by social desirability bias. Consequently, it is important to use objective measurements in future research to mitigate this potential bias.

Furthermore, the study’s dependence on survey tools that were developed by the researchers themselves raises apprehensions regarding the reliability and validity of the findings. The qualitative data obtained from students who engage in offline learning, while possessing inherent value, may be subject to certain limitations in terms of its reach. Moreover, there is a lack of comprehensive exploration regarding contextual changes in both online and offline learning environments, as well as the impact of cultural influences on the dynamics of peer feedback. Furthermore, the study does not establish a causal relationship or determine the direction of influence between the variables under observation. To enhance our understanding of the involvement of English as a Foreign Language (EFL) students in peer feedback exercises and their influence on language acquisition results, it is imperative to address these constraints in future research endeavors.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this research aimed to examine students’ engagement in online and offline learning environments in EFL contexts. The results showed that both groups of students had equally positive perceptions of the usefulness of peer feedback and their self-perceived English proficiency levels and writing skills. However, online students showed a higher appreciation of reading and giving peer feedback than offline students. Despite this, none of the peer feedback activities significantly contributed to the writing outcomes of EFL students across different learning environments. These findings suggest that while peer feedback activities may be valued and perceived as useful by students, they may not have a significant impact on writing outcomes. Further research is needed to explore other factors that may contribute to the improvement of EFL writing skills.

Availability of data and materials

Data are available upon request.

References

Al Abri, A., Al Baimani, S., & Bahlani, S. (2021). The role of web-based peer feedback in advancing EFL essay writing. Computer-Assisted Language Learning Electronic Journal (CALL-EJ), 22(1), 374–390.

Apridayani, A., & Waluyo, B. (2022). Antecedents and effects of students’ enjoyment and boredom in synchronous online English courses. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2022.2152457.

Astrid, A., Rukmini, D., & Fitriati, S. W. (2021). Experiencing the peer feedback activities with teacher’s intervention through Face-to-face and Asynchronous Online Interaction: The impact on students’ writing development and perceptions. Journal of Language and Education, 7(2), 64–77.

Berg, E. C. (1999). The effects of trained peer response on ESL students’ revision types and writing quality. Journal of Second Language Writing, 8(3), 215–241.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

Braun, V., Clarke, V., & Terry, G. (2015). Thematic analysis. In P. Rohleder, & A. Lyons (Eds.), Qualitative research in clinical and health psychology (pp. 95–113). Palgrave MacMillan.

Ciftci, H., & Kocoglu, Z. (2012). Effects of peer e-feedback on Turkish EFL students’ writing performance. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 46(1), 61–84.

Creswell, J., & Plano Clark, V. (2007). Designing and conducting mixed methods research. Sage.

Dressler, R., Chu, M. W., Crossman, K., & Hilman, B. (2019). Quantity and quality of uptake: Examining surface and meaning-level feedback provided by peers and an instructor in a graduate research course. Assessing Writing, 39, 14–24.

Fan, Y., & Xu, J. (2020). Exploring student engagement with peer feedback on L2 writing. Journal of Second Language Writing, 50, 100775.

Farahani, A. A. K., Nemati, M., & Nazari Montazer, M. (2019). Assessing peer review pattern and the effect of face-to-face and mobile-mediated modes on students’ academic writing development. Language Testing in Asia, 9, 1–24.

George, D., & Mallery, P. (2003). SPSS for Windows step by step: A simple guide and reference, 11.0 update (4th ed.). Allyn & Bacon.

Guo, Y., Wang, Y., & Ortega-Martín, J. L. (2023). The impact of blended learning-based scaffolding techniques on learners’ self-efficacy and willingness to communicate. Porta Linguarum Revista Interuniversitaria De Didáctica De las Lenguas Extranjeras, 40, 253–273.

Hu, G. (2005). Using peer review with Chinese ESL student writers. Language Teaching Research, 9(3), 321–342.

Huisman, B., Saab, N., Van Driel, J., & Van Den Broek, P. (2020). A questionnaire to assess students’ beliefs about peer-feedback. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 57(3), 328–338. https://doi.org/10.1080/14703297.2019.1630294.

Hyland, K., & Hyland, F. (2019). Feedback in second language writing: Contexts and issues. Cambridge University Press.

Ivankova, N. V., Creswell, J. W., & Stick, S. L. (2006). Using mixed-methods sequential explanatory design: From theory to practice. Field Methods, 18(1), 3–20.

Jin, X., Jiang, Q., Xiong, W., Feng, Y., & Zhao, W. (2022). Effects of student engagement in peer feedback on writing performance in higher education. Interactive Learning Environments, Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2022.208120.

Jongsma, M. V., Scholten, D. J., van Muijlwijk-Koezen, J. E., & Meeter, M. (2022). Online versus offline peer feedback in higher education: A meta-analysis. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 61(2), 329–354. https://doi.org/10.1177/07356331221114181.

Karim, K., & Nassaji, H. (2020). The revision and transfer effects of direct and indirect comprehensive corrective feedback on ESL students’ writing. Language Teaching Research, 24(4), 519–539.

Kerman, N. T., Noroozi, O., Banihashem, S. K., Karami, M., & Biemans, H. J. (2022). Online peer feedback patterns of success and failure in argumentative essay writing. Interactive Learning Environments, 32(2), 614–626. https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2022.2093914.

Latifi, S., Noroozi, O., & Talaee, E. (2021). Peer feedback or peer feedforward? Enhancing students’ argumentative peer learning processes and outcomes. British Journal of Educational Technology, 52(2), 768–784.

Lee, M. K., & Evans, M. (2019). Investigating the operating mechanisms of the sources of L2 writing self-efficacy at the stages of giving and receiving peer feedback. The Modern Language Journal, 103(4), 831–847.

Loan, N. T. T. (2017). A case study of combined peer-teacher feedback on paragraph writing at a university in Thailand. Indonesian Journal of Applied Linguistics, 7(2), 253–262.

Lv, X., Ren, W., & Xie, Y. (2021). The effects of online feedback on ESL/EFL writing: A meta-analysis. The Asia-Pacific Education Researcher, 30(6), 643–653.

Ma, Q. (2020). Examining the role of inter-group peer online feedback on wiki writing in an EAP context. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 33(3), 197–216.

Majid, N., & Islam, M. (2021). Effectiveness of peer Assessment and peer feedback in Pakistani context: A case of University of the Punjab. Bulletin of Education and Research, 43(2), 101–122.

Meletiadou, E. (2021). Exploring the impact of peer Assessment on EFL Students’ writing performance. IAFOR Journal of Education, 9(3), 77–95.

Min, H. T. (2016). Effect of teacher modeling and feedback on EFL students’ peer review skills in peer review training. Journal of Second Language Writing, 31, 43–57.

Nguyen, T. T. L. (2018). The effect of combined peer-teacher feedback on Thai Students’ writing accuracy. Iranian Journal of Language Teaching Research, 6(2), 117–132.

Nguyen, C. D. (2021). Lexical features of reading passages in English-language textbooks for Vietnamese high-school students: Do they foster both content and vocabulary gain? Relc Journal, 52(3), 509–522. https://doi.org/10.1177/003368821989504.

Novakovich, J. (2016). Fostering critical thinking and reflection through blog-mediated peer feedback. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 32(1), 16–30.

Novakovich, J., & Long, E. C. (2013). Digital performance learning: Utilizing a course weblog for mediating communication. Journal of Educational Technology & Society, 16(4), 231–241.

Pham, T. N., Lin, M., Trinh, V. Q., & Bui, L. T. P. (2020). Electronic peer feedback, EFL academic writing and reflective thinking: Evidence from a confucian context. Sage Open, 10(1), 2158244020914554.

Pratiwi, D. I., & Waluyo, B. (2023). Autonomous Learning and the Use of Digital Technologies in Online English classrooms in Higher Education. Contemporary Educational Technology, 15(2), 1–16.

Rahayu, N. S., Mukminatien, N., & Sukarsono, U. M. (2022). Exploring EFL Students’ Writing Engagement Using Google Docs as a Peer Feedback Platform. Hong Kong Journal of Social Sciences.

Rezai, A. (2022). Cultivating Iranian IELTS candidates’ writing skills through online peer feedback: A mixed methods inquiry. Education Research International, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/6577979.

Saeli, H., & Cheng, A. (2021). Peer feedback, Learners’ Engagement, and L2 writing development: The case of a Test-Preparation Class. Tesl-Ej, 25(2), n2.

Sedgwick, P. (2013). Convenience sampling. Bmj, 347.

Sha, L., Wang, X., Ma, S., & Mortimer, T. A. (2022). Investigating the effectiveness of anonymous online peer feedback in translation technology teaching. The Interpreter and Translator Trainer, 16(3), 325–347.

Shang, H. F. (2017). An exploration of asynchronous and synchronous feedback modes in EFL writing. Journal of Computing in Higher Education, 29, 496–513.

Shi, Y. (2021). Exploring learner engagement with multiple sources of feedback on L2 writing across genres. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 758867.

Sun, P. P., & Zhang, J. L. (2022). Effects of translanguaging in online peer feedback on Chinese University English-as-a-foreign-language students’ writing performance. RELC Journal, 53(2), 325–341.

Teng, L. S., & Zhang, L. J. (2020). Empowering learners in the second/foreign language classroom: Can self-regulated learning strategies-based writing instruction make a difference? Journal of Second Language Writing, 48, 100701.

Thi, N. K., Nikolov, M., & Simon, K. (2023). Higher-proficiency students’ engagement with and uptake of teacher and Grammarly feedback in an EFL writing course. Innovation in Language Learning and Teaching, 17(3), 690–705. https://doi.org/10.1080/17501229.2022.2122476.

Tian, L., & Li, L. (2018). Chinese EFL learners’ perception of peer oral and written feedback as providers, receivers and observers. Language Awareness, 27(4), 312–330.

Tian, L., & Zhou, Y. (2020). Learner engagement with automated feedback, peer feedback and teacher feedback in an online EFL writing context. System, 91, 102247.

Van Popta, E., Kral, M., Camp, G., Martens, R. L., & Simons, P. R. J. (2017). Exploring the value of peer feedback in online learning for the provider. Educational Research Review, 20, 24–34.

Vuogan, A., & Li, S. (2023). Examining the effectiveness of peer feedback in second language writing: A metaanalysis. Tesol Quarterly, 57(4), 1115–1138.

Waluyo, B., & Bakoko, R. (2021). Vocabulary list learning supported by gamification: Classroom action research using quizlet. Journal of Asia TEFL, 18(1), 289–299.

Waluyo, B., & Panmei, B. (2024). Students’ peer feedback engagements in online English courses facilitated by a social network in Thailand. Journal of Technology and Science Education, 14(2), 306–323.

Waluyo, B., Apridayani, A., & Arsyad, S. (2023). Using writeabout as a Tool for Online writing and feedback. Teaching English as a second Language Electronic Journal (TESL-EJ), 26(3), n4.

Wang, W. (2014). Students’ perceptions of rubric-referenced peer feedback on EFL writing: A longitudinal inquiry. Assessing Writing, 19, 80–96.

Wang, Y., Wang, Y., Pan, Z., & Ortega-Martín, J. L. (2023). The predicting role of EFL students’ achievement emotions and technological self-efficacy in their technology acceptance. The Asia-Pacific Education Researcher, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-023-00750-0.

Wu, Y., & Schunn, C. D. (2020). When peers agree, do students listen? The central role of feedback quality and feedback frequency in determining uptake of feedback. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 62, 101897.

Wu, W., Huang, J., Han, C., & Zhang, J. (2022). Evaluating peer feedback as a reliable and valid complementary aid to teacher feedback in EFL writing classrooms: A feedback giver perspective. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 73, 101140.

Xu, Z., Zhang, L. J., & Parr, J. M. (2023). Incorporating peer feedback in writing instruction: examining its effects on Chinese English-as-a-foreign-language (EFL) learners’ writing performance. International Review of Applied Linguistics in Language Teaching, 61(4), 1337–1364. https://doi.org/10.1515/iral-2021-0078.

Yang, Y. F. (2016). Transforming and constructing academic knowledge through online peer feedback in summary writing. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 29(4), 683–702.

Zhan, Y., Wan, Z. H., & Sun, D. (2022). Online formative peer feedback in Chinese contexts at the tertiary level: A critical review on its design, impacts and influencing factors. Computers & Education, 176, 104341.

Zhan, Y., Yan, Z., Wan, Z. .H., Wang, X., Zeng, Y., Yang, M., & Yang, L. (2023). Effects of online peer assessment on higher-order thinking: A meta‐analysis. British Journal of Educational Technology, 54(4), 817–35.

Zhang, M., He, Q., Du, J., Liu, F., & Huang, B. (2022). Learners’ perceived advantages and social-affective dispositions toward online peer feedback in academic writing. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 973478.

Informed consent statement

Prior to their participation in this study, all students involved were fully informed about the research objectives and protocols. They provided voluntary consent to take part in the research, demonstrating their willingness to engage in the study activities. Their participation was entirely voluntary and free from any form of coercion or external pressure.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Budi Waluyo conducted the research, gathered and analyzed the data. B.D. wrote the main manuscript text. Tipaya Peungcharoenkun served as the research assistant who arranged data and wrote some assigned parts of the manuscript. B.D. and T.P. reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This research was conducted without formal ethical approval, as the opportunity to submit an Institutional Review Board (IRB) application was inadvertently missed. However, it is important to note that all research procedures adhered to the ethical principles commonly upheld in social science research. Additionally, the Head of Research at our institution was aware of and informed about this research study.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1

The peer review form for surveys

Appendix 2

The peer review form for Survey Reports

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Peungcharoenkun, T., Waluyo, B. Students’ affective engagements in peer feedback across offline and online English learning environments in Thai higher education. Asian. J. Second. Foreign. Lang. Educ. 9, 60 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40862-024-00286-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40862-024-00286-w