Abstract

Background

Populations of Eastern Whip-poor-will (Antrostomus vociferous) appear to be declining range-wide. While this could be associated with habitat loss, declines in populations of many other species of migratory aerial insectivores suggest that changes in insect availability and/or an increase in the costs of migration could also be important factors. Due to their quiet, nocturnal habits during the non-breeding season, little is known about whip-poor-will migration and wintering locations, or the extent to which different breeding populations share risks related to non-breeding conditions.

Results

We tracked 20 males and 2 females breeding in four regions of Canada using geolocators. Wintering locations ranged from the gulf coast of central Mexico to Costa Rica. Individuals from the northern-most breeding site and females tended to winter furthest south, although east-west connectivity was low. Four individuals appeared to cross the Gulf of Mexico either in spring or autumn. On southward migration, most individuals interrupted migration for periods of up to 15 days north of the Gulf, regardless of their subsequent route. Fewer individuals showed signs of a stopover in spring.

Conclusions

Use of the southeastern United States for migratory stopover and a concentration of wintering locations in Guatemala and neighbouring Mexican provinces suggest that both of these regions should be considered potentially important for Canadian whip-poor-wills. This species shows some evidence of both “leapfrog” and sex-differential migration, suggesting that individuals in more northern parts of their breeding range could have higher migratory costs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

At high latitudes, over 80% of bird species are migratory [1]. Migration increases exposure to novel challenges, including pathogens, predators, and anthropogenic threats at geographically disparate locations [1, 2]. Cumulatively the energetic, time, and fatality costs associated with these long journeys can account for most annual mortality for some species [3,4,5] and can influence survival and productivity in subsequent seasons [6,7,8,9]. Depending on the relative costs and benefits [5, 10, 11], individual strategies relating to the timing and speed of migration, migratory routes, and winter destinations vary widely both within [12,13,14] and between species [15,16,17]. Some birds build up large reserves of fat to fuel long flights across inhospitable habitats or barriers [18, 19], while others employ fly-and-forage strategies that allow lower weight burdens and reduced time spent at stopover locations [20]. Crossing barriers, such as large bodies of water, likely increases the time required to build up fuel reserves and increases risks associated with abrupt changes in weather, but may help migrants to avoid predation and reduce transit time associated with longer over-land detours [21].

Migratory strategies that allow individuals to track seasonal variation in resources may be particularly important for temperate breeding aerial insectivores (i.e., birds that specialize in catching and eating flying insects while they themselves are also in flight). In temperate climates, insect flight periods are ultimately limited by seasonal changes in temperature [22]. While some insectivorous birds that pursue dormant prey in sheltered hiding places can overwinter in temperate regions (e.g., woodpeckers), most aerial insectivores must migrate to ensure an adequate supply of flying insects. Even when prey is abundant, this foraging strategy is sensitive to the high energetic costs of flight for both predator and prey during inclement weather. Unseasonably cold, or extreme, weather can kill or make prey less accessible to predators [23, 24]. This sensitivity to weather could increase selective pressure on the timing, migration routes, and choice of winter habitat [11, 25].

Population declines among many temperate breeding aerially insectivore birds may be partially due to recent increases in the frequency of extreme weather events [26], interacting with existing costs of migration and a reliance on weather-sensitive prey [27,28,29,30]. For example, long-term decreases in body mass found in a declining swallow population, which could not be explained by changes in breeding habitat quality, suggest a carry-over of change in migration or wintering conditions [31]. In addition, the degree of connectivity between populations on the breeding and wintering grounds can buffer or exacerbate a loss of habitat at other locations used throughout the annual cycle [32,33,34]. Therefore, to understand and mitigate threats to aerial insectivores, it is important to identify the year-round geographic and habitat requirements, migratory routes, and temporal constraints of individuals belonging to threatened populations [35, 36].

Nightjars may be especially sensitive to inclement weather, because they are limited to foraging on flying insects only at dawn and dusk, or on moonlight nights, when there is adequate light to see their prey [37, 38]. The only two species of Neotropical migrant nightjars that occur at high latitudes in North America differ in foraging strategy, migratory distance, and breeding site fidelity, and still both are listed as threatened. The Eastern Whip-poor-will (Antrostomus vociferous) is a sally-foraging, medium-distance migrant, with high breeding site fidelity, whose populations appear to be declining range-wide. Due to their quiet, nocturnal habits during the non-breeding season, little is known about when and where changes in food availability could influence this population. We seek to fill this knowledge gap by identifying wintering locations, migratory routes and stopovers, and variation in timing of movements, with respect to breeding origin and sex. This is not only the first examination of these parameters for Eastern Whip-poor-wills, but the first for any Neotropical migrant nightjar.

Methods

Study locations/sites

We deployed light-logging geolocation tags (Fig. 1), hereafter “geolocators”, in four regions spanning a 1000 km stretch of the species’ range in Ontario, Canada: Rainy River District, Norfolk County, Muskoka District Municipality, and Frontenac County (Fig. 2). The Rainy River site (48° 49–59’N 94° 0–21’W) consisted of a 40000-hectare mosaic of agriculture, poplar (Populus sp.), coniferous forests, logged areas, and wetlands. The Norfolk County site (42° 42’N 80° 21–28’W) was St. Williams Conservation Reserve, which consists of two forest patches totaling 1035 hectares of pine-oak sand barrens and pine reforestation in a zone of intensive agriculture. The Muskoka district sites (including portions of neighbouring Parry Sound District and Simcoe County; 44° 22–56’N 79° 08–47’W) contained extensive pine-oak rock barrens. The Frontenac County site (44° 28–34’N 76° 20–25’W) was Queen’s University Biological Station, which consists of over 3200 hectares of deciduous forest and abandoned farmland in various stages of succession, both with scattered small rock barrens.

Median estimated wintering location and interquartile ranges for whip-poor-wills from four breeding sites in Canada. Map covering southeastern North America and Central America from ‘mapdata’ package in R [90], with a shaded area representing the breeding range of Eastern Whip-poor-wills [53]. Colours indicate breeding origin (blue: Rainy River, green: Muskoka, red: Frontenac, orange: Norfolk), and shapes indicate sex (open squares: male, filled circles: female)

Field methods/geolocator deployment

We captured and banded adult/after hatch-year whip-poor-wills between 5 May and 25 July in 2011–2013. We captured male whip-poor-wills at night using mist nets and song playback at all sites. We only targeted females in Frontenac, where we captured them on nests by placing a soft mesh fishnet over them while they were incubating. All birds received a numeric aluminum leg-band issued by the Canadian Wildlife Service.

Geolocator tags record and store time and light-level data that can be used to estimate latitude and longitude based on sunrise and sunset timing. Birds must be recaptured to retrieve the tags and download the data. We deployed 65 LightBug geolocator tags (Lotek, Newmarket, Ontario, Canada; Fig. 1) during the 2011 and 2012 breeding seasons. We fitted tags to individual birds using a leg loop harness [39] made of 2.5 mm Teflon ribbon and secured with a cyanoacrylate-glued square knot. Total weight of the tag and gear was approximately 2.7 g. We deployed 59 tags on males (Rainy River: 5, Norfolk: 14, Muskoka: 24, Frontenac: 16) and 6 on females. Six returning males received tags in two consecutive years. Whip-poor-wills captured in this study weighed 46.7–67.5 g (mean = 57.8 g), but no birds weighing < 54 g were fitted with geolocators. Geolocators with harnesses amounted to 4–5% of body mass [40, 41]. An additional 36 birds weighing > 54 g were banded, but did not receive geolocators (Rainy River: 10, Norfolk: 2, Frontenac: 24).

Recapture/return rates

We compared the combined effect of survival and site fidelity for banded birds with and without geolocators. We attempted to recapture birds at all sites and banding locations where birds had been fitted with geolocator tags the previous year, but effort varied in duration, date, moon phase, and weather between sites and years. To retrieve tags from females, we searched for nests on all territories on which females were tagged in the previous year. We also attempted to capture birds in territories adjacent to those where geolocators had been deployed the previous year. We were unable to recapture all birds occupying sites where geolocators had been deployed the previous year; therefore, we estimated return rates only for territories on which individuals of the same sex were successfully captured in two consecutive years.

Geolocator analysis/data processing

LightBug geolocators were programmed to record the intensity of blue light every 8 min for up to one year. Horizon clutter and clouds affect blue light less than other wavelengths [42]. Using Lotek’s LAT Viewer Studio Software, these recorded light values were compared with a template of how blue light levels should change at twilight and location estimates were produced along with an error estimate based on the fit of the data [43]. The template fit method is less sensitive to daily variation in cloud cover and ambient light intensity than the threshold method [41,44,, 43–45]. This method also allows for the possibility of estimating latitude during the equinox, although with greater error than at other times of the year. The template fit method is still sensitive to short term fluctuations in light conditions, including those resulting from the behaviour of crepuscular animals like whip-poor-wills [44]. Because our tags used a proprietary data format and our light-level data was extremely noisy (making it necessary to manually select which peaks qualified as true sunrises or sunsets for most analysis packages), we could not easily apply recent advances in movement modeling, such as FlightR, to our data [45]. Our template fit method instead provided an objective way of assessing reliability of individual light curves by incorporating deviations from a smooth curve into error estimates [46].

We used a series of criteria to filter the daily latitude and longitude estimates to exclude points with limited precision or that were biologically impossible. Latitude and longitude were analyzed independently because they respond to noise in the light signals differently [43, 47]. First, we included only location estimates within the species’ plausible geographic range (between 0° and 58° latitude and –60° and –110° longitude). This resulted in average exclusion of 26% of latitude estimates and 4% of longitude estimates. Second, we excluded points with error estimates (provided by LAT Viewer) of > 15° and > 5° for latitude and longitude respectively. We used different thresholds because estimates of latitude have more error than estimates of longitude [43, 47]. These thresholds excluded another 20% percent of plausible estimates. Third, we removed estimates that required birds to travel > 800 km in a day (similar to Fraser et al. 2012). We chose 800 km as a cut-off distance because it allows for some error beyond the maximum average migration rate recorded for small birds of 500–600 km day−1 [48, 49]. Finally, we excluded estimates that required a redundant movement of 800 km (i.e., movements of 800 km away from and back to average weekly longitude or latitude) even when daily movements were < 800 km. The resulting proportion of missing days per bird per year averaged 31% (range: 4–72%) for longitude and 62% (range: 37–93%) for latitude. To evaluate the accuracy of these location estimates we compared capture locations with average longitude and latitude values obtained for the breeding season (15 May to 31 Aug). The average difference between median of breeding season estimates and the actual capture location was -0.20° (-2.96°–0.93°) for longitude and –0.43° (–7.90°–2.17°) for latitude [see Additional file 1: Figure S1].

Wintering range

A qualitative examination of latitude and longitude estimates plotted independently against time (see [Rakhimberdiev et al. 2016] for example plots) provided no evidence that whip-poor-will used multiple wintering sites (i.e. no shifts away from the median value that consistently exceeded the variance in our estimates). Therefore, we defined wintering location of each bird as the median latitude and longitude estimates obtained between 15 Dec (the latest date individuals arrive on their wintering grounds, see Results) and 28 Feb (day before the earliest estimated start of spring migration, see Results). We illustrate the uncertainty in this estimate using interquartile ranges.

Migratory behaviour

For Ontario whip-poor-wills, departure from both breeding and wintering grounds occurs near the equinoxes, so longitude data were used to estimate the start of migratory behaviour for birds from the more eastern study sites (Norfolk, Muskoka, and Frontenac). The two Rainy River birds were not included in this analysis because their tags did not detect any longitudinal movement at the start of autumn migration and both tags stopped collecting data prior to spring migration. Latitude data were used in estimating the end dates of migration only when the wintering/breeding latitude was reached after reaching the wintering/breeding longitude.

Due to variation in the number of retained location estimates, and the variance in the precision of these estimates, we used a range of dates to estimate migratory transitions. We defined the start of migration as the mid-point between the last day in a series of 2 consecutive samples (< one week apart) that are within 1 standard deviation of the mean breeding ground longitude (68% probability that the bird is still at the breeding ground longitude) and the day prior to first 2 consecutive samples that are in the direction of subsequent movement and outside 1 standard deviation (68% probability that the bird is no longer at breeding ground longitude). Similarly, arrival on the wintering grounds was defined as the midpoint between the last day in a series of 2 consecutive samples that are in the direction of previous movement and outside 1 standard deviation of the wintering longitude and latitude (68% probability that the bird is not yet at the wintering longitude) and the first 2 consecutive samples that are within 1 standard deviation of mean wintering longitude (68% probability that the bird has reached wintering longitude). This threshold produces a larger and more conservative range of estimates for departure/arrival dates than a 95% probability threshold. The degree of uncertainty in each of these estimates was defined as the number of days between the two dates used to calculate each midpoint. For statistical analysis, we excluded those estimates with > 7 days uncertainty.

While the lack of latitude estimates for many days during this migratory period makes identification of precise migratory routes impossible, broad patterns in the duration of migration, stopover use, and route around the Gulf of Mexico were identifiable for some individuals. We defined duration of migration as the time between the estimated start and end of autumn and spring migrations, including any time spent at stopover locations. Duration estimates derived from start and end dates with total combined uncertainty of > 14 days were excluded from further analysis. Stopovers were identified by visual inspection of temporal changes in longitude to identify periods of at least 4 days without any consecutive days with forward progress of > 2° longitude.

At least 3 days would be required for a bird flying at a maximum of 500 km/day (487 km/day was maximum rate estimated for another nightjar Caprimulgus europaeus [50]) to travel the 1500 km of the gulf shoreline that lies furthest west, between 95° and 98°W. Therefore, flight over some portion of the Gulf of Mexico was assumed to have occurred where mean wintering latitude was south of 25°N and east of 95°W, and when < 3 consecutive samples during the migratory period were west of 95° and any periods of missing data during this stage of migration were also < 3 days.

In total, we were able to estimate: timing of departure from breeding longitude for 11 individual annual cycles (Norfolk: 1, Frontenac: 7, Muskoka: 3), arrival at winter longitude for 15 (Frontenac: 8, Muskoka: 7), duration of autumn migration for 11 (Frontenac: 7, Muskoka: 4), departure from wintering longitude for 7 (Norfolk: 1, Frontenac: 2, Muskoka: 4), duration of spring migration for 11 (Norfolk: 1, Frontenac: 5, Muskoka: 6), and arrival at breeding longitude for 15 (Norfolk: 1, Frontenac: 7, Muskoka: 7). We were able to estimate the location and time spent at stopover sites for 12 autumn (Frontenac: 6, Muskoka: 6) and 4 spring migrations (Norfolk: 1, Frontenac: 2, Muskoka: 1), and to determine whether individuals crossed or travelled around the Gulf of Mexico for 12 autumn (Frontenac: 5, Muskoka: 7) and 10 spring migrations (Frontenac: 3, Muskoka: 7).

Statistical analysis

We examined i) the correlation between the wintering latitudes and longitudes with the breeding origins for all males (if data were obtained for two years we used the year with more winter locations), ii) sex differences in winter latitude and longitude using data from birds captured in central Ontario (Muskoka and Frontenac sites that share similar latitude and habitat types), and iii) interannual variation in wintering latitude for males tracked twice. For all tracks with sufficient daily resolution (see Migratory Behaviour), we classified migratory routes qualitatively and estimated duration of stopovers. Finally, we estimated i) the variation among individual males in the departure, arrival, and duration of autumn and spring migration (when timing did not differ significantly between years, we pooled inter-individual variation in migratory timing across years), and ii) interannual variation in the timing of migration for males tracked twice. We report raw differences in timing between the sexes, but do not apply statistical tests due to the small sample sizes. We used non-parametric statistical tests (Kendall rank correlation or Wilcox rank sum tests) in R [51].

Results

Return rates

We captured territorial males at 45 of the 59 sites where a geolocator was deployed in the previous year, and in 23 of those 45 cases we recaptured the same individual. We retrieved two additional tags: one two years after it was deployed, and one from a male that had moved to an adjacent territory. We captured a territorial male at 19 of the 36 sites where males weighing > 54 g were banded but did not receive geolocators; 12 of these were returning males. A combination of annual survival and territory fidelity resulted in territory specific return rates of 51% (23 of 45) for males with geolocators and 63% (12 of 19) for banded males without geolocators (chi-square = 0.68, df = 1, p = 0.41). We only captured females on 3 territories in which females were tagged the previous year and 2 (67%) were returning females.

Wintering range

Light data were recorded on 24 of 25 geolocator tags retrieved from males, and both tags retrieved from females. Four males were tracked successfully for two consecutive years. Therefore, we determined the winter locations for 22 individual birds [see Additional file 2: Table S1]. These locations ranged from the gulf coast of central Mexico to Costa Rica (Fig. 2). Median wintering latitudes for 20 males ranged from 10° to 30°N (10° to 24°N for 15 males with > 20 estimates). Males from more northern breeding sites wintered further south (Kendall’s rank correlation tau = -0.33 z = -2, p = 0.04, N = 20). Female median wintering latitudes were 9° and 10°N, which are both farther south than all but one male from similar breeding latitude (Wilcox rank sum W = 3, p = 0.03, N = 15, 2). Median wintering longitudes ranged from –86° to –98°, were not related to breeding longitude for males (Kendall’s rank correlation tau =–0.005, z =–0.03, p = 1, N = 20), and did not differ between the sexes (Wilcox rank sum W = 24, p = 0.2, N = 15, 2). Three of the four males tracked in two years appeared to overwinter in the same location; interquantile ranges for both latitude and longitude estimates overlap between years (Fig. 3). The winter site fidelity of the remaining male was uncertain because we only obtained estimates of its winter location for 7 days in 2012/13.

Winter location for three males each with two years with > 20 days of winter latitude and longitude estimates (squares: 2011, triangles: 2012) displayed over country and shoreline boundaries [90]

Migratory route and stopovers

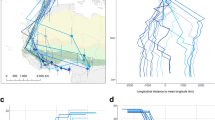

In autumn, ten individual males (including both years for one bird) and both females, all from central Ontario populations, appeared to stop migrating for between 4 and 15 days along the north coast of the Gulf of Mexico between 83° and 96°W (pooled median = 30°N, 89°W; Fig. 4a). After these stopovers, one male crossed the gulf, another continued west to winter on the gulf coast of Mexico (19°N, 98°W; QU907), 8 individuals travelled southwest around the gulf and then east into southwestern Mexico or Central America, and for two the path was uncertain. Another male crossed the Gulf of Mexico during southward migration without stopping for a detectable length of time (4 days). One female and 1 male appeared to stopover a second time south of the Gulf of Mexico (26–13°N, 91–94°W) before continuing south another ~5° latitude.

Stopover locations (median with interquartile ranges) for all birds that halted longitudinal progress for ≥ 4 days during either migratory period. We estimate latitude for individuals where possible, or based on pooled estimates for all individuals showing signs of stopover during the same time period. Map outlines [90], colours indicating breeding origin (green: Muskoka, red: Frontenac, orange: Norfolk), and shapes indicating sex (open squares: male, filled circle: female) are the same as in Figure 2

In spring, one female appeared to stop on the Yucatan Peninsula for 10 days (1–11 Mar) and showed evidence of a 6-day stopover north of the Gulf (1–7 May), but it was unclear whether she crossed or circumnavigated the Gulf. Three males, at least one of which circumnavigated the Gulf, showed evidence of a stopover north of the Gulf for between 7 and 12 days at a median of 30°N and 90°W (start: 2–22 Apr 2012; end: 8–29 Apr 2012; Fig. 4b). Two males crossed the Gulf without evidence of any stopovers.

Variation in timing

Across all males, variation in timing of migratory behaviour was much less (<18 days) for both departure from and arrival at breeding longitudes than for arrival at and departure from wintering longitudes (>38 days; Fig. 5), but overall duration of spring and autumn migration was not different (autumn: median = 42.5, range = 26.5–68; spring: median = 37, range = 23–58; W = 31, p = 0.4). Arrival dates on both wintering and breeding grounds were not correlated with timing of departure, or wintering latitude or longitude (all p > 0.2).

Mean male dates of departure from the breeding grounds, departure from the wintering grounds, and return to the breeding grounds did not differ between years (N ≥ 6 and 2, p ≥ 0.1). However, males arrived at their wintering longitude later in 2012 than 2011 (mean = 1 Dec and 9 Nov respectively, N = 10 and 4, p = 0.02). Only one individual (Frontenac 898 in Fig. 3) had reliable timing estimates for both years; he left the breeding grounds earlier (3–9 days), but arrived on (7–15 days) and left from (1–33 days) the wintering grounds later in the 2012/2013 non-breeding season than in the previous year. In contrast, this male appeared to arrive on the breeding grounds on the same day in both years (range: 5 days later to 7 days earlier).

In autumn, male whip-poor-wills departed from breeding longitudes in Ontario between 25 Sept and 11 Oct (mean = 2 Oct, N = 9). They arrived on wintering longitudes between 2 Nov and 3 Dec (mean = 16 Nov, N = 12). The minimum duration of travel was 27 (± 4) days for a male from Frontenac, which wintered in central Mexico (19.11°N, 97.91°W), covering an estimated minimum distance of 2260 km at a rate of 135 km/day. The next shortest duration of 32 (± 1) days belonged to a male from Muskoka, which wintered furthest south of all males with reliable duration estimates at (13.9°N, 90.25°W), requiring a minimum travel distance of 3637 km, and yet also travelled an average of 135 km/day. We could not assess whether males that crossed the gulf spent less time on migration, because no birds with ≤ 14 days uncertainty in duration appeared to cross the Gulf.

In spring, male whip-poor-wills departed from wintering longitudes between 1 Mar and 9 Apr (mean = 21 Mar, N = 7). Arrival at breeding longitude ranged from 19 Apr to 7 May (mean = 1 May, N = 13). The shortest migration time was 23 (± 2) days for a Muskoka male that wintered in Campeche, Mexico and travelled west around the Gulf covering an estimated 4160 km at a mean rate of 180 km/day. Of two males that crossed the Gulf, the only male with accurate timing estimates took only 24 (± 4) days to cover a minimum of 3650 km for an average travel rate of 152 km/day.

Sex differences

The two females from which we retrieved geolocators appear to have departed later than males (1 Oct and 13 Oct), spent more time on autumn migration (53 and 58 days versus mean of 45 days for males), arrived later on wintering grounds (28 Nov and 5 Dec), and departed earlier from winter longitude (27 Feb and 17 Mar). The two females also took on average 30 days longer (56 and 75 days vs. mean = 36.1, N = 8, SD = 12.6 for males) and arrived at breeding longitudes after 10 May in contrast to a mean arrival of 30 Apr for males (N = 12, SD = 5.65). Neither female appeared to cross the Gulf in either season.

Discussion

Winter location and connectivity

Our results suggest that whip-poor-wills breeding in the more northern parts of their breeding range may experience different wintering conditions and have higher migratory costs, in terms of energy expenditure, novel threats, and ability to adjust arrival time to track breeding ground conditions [52], than more southern breeding populations. Whip-poor-wills from sites across their Ontario breeding range showed some evidence of “leapfrog”, and perhaps sex-differential, migration. More northerly breeding individuals and females wintered to the south of more southerly breeding individuals, and the vast majority of males. While most individuals wintered within the well-established winter range for this species [53], 3 birds (including both females) wintered south of the Honduras-Nicaragua border, a latitude where whip-poor-wills are described as only “a casual to very rare winter resident” [54]. Given that Ontario is on the northern edge of the breeding range, this pattern is reinforced by these 3 birds appearing to winter south of the usual winter range, and not finding any birds overwintering within the most northern portions of the known winter range (with the possible exception of a single bird with only 9 days of winter latitude data). In contrast, both eastern and western-most breeding individuals wintered together, concentrated in Guatemala and neighbouring provinces of Mexico, suggesting low connectivity between breeding longitude and wintering location [33, 55]. Although population data for whip-poor-wills lacks the precision to effectively compare regional population trajectories, given that there are regional differences in population trends for other aerial insectivores [56], leapfrog migration patterns may help explain regional differences in breeding ground population trends that are not obviously linked to local changes in habitat.

Both inter-population leapfrog migration patterns and differential migration between sexes have been attributed to differences in the importance of arrival timing, asymmetric competition, or differences in cold tolerance due to body size differences [52]. Males often experience higher net benefits of early arrival on the breeding grounds [57,58,59,60] and may therefore accept higher costs of wintering further north [52]. Likewise, populations breeding further south may benefit more from being able to track spring phenology more closely [61]. The earlier spring arrival and shorter migration times we found for male whip-poor-wills suggest that early arrival on breeding grounds is more beneficial for males, potentially allowing occupation of higher quality territories. Females could be forced to migrate further by lower competitive abilities, or to exploit more abundant resources at lower latitudes [52]. However, more information on winter territoriality and resource use by whip-poor-wills is required before these hypotheses could be fully developed and tested.

For a few individuals, our geolocator data suggest biologically impossible wintering locations that are over the open ocean. Wintering locations estimated using the timing of dusk and dawn could be biased for two reasons: i) Steep mountain slopes could consistently skew sunrise or sunset by shading from the terrain [47, 62]. This could explain the aberrant points if the three southern-most birds were wintering on a west-facing slope of the continental divide in Central America, where sunrise was skewed later, causing them to appear further west and north than the actual wintering location. ii) Abrupt changes in light levels can cause smoothed light curves to appear steeper than if shading remained constant. However, this cannot explain our southern-most points, because this would cause the true winter latitude would be closer to the equator (by up to 1.4°) than the estimated location, placing the actually winter location even further into the ocean [44].

Variation in migratory route and stopover

It is generally assumed that most whip-poor-wills travel overland through Mexico and Central America [53]. Our data, however, suggest that flights across some portion of the Gulf of Mexico were undertaken by at least two individuals in autumn and two different individuals in the spring. That at least some whip-poor-wills attempt Gulf crossings is supported by vagrant records for Cuba and the Caribbean islands [53, 63] and by one e-bird (http://ebird.org/) record from off-shore in the Gulf from 12 Oct 2011.

Similar numbers of Gulf crossings in both seasons are somewhat surprising given that loop migrations in which spring migration routes are west of autumn routes seem to be most common in both Neotropical [17, 21, 64, 65] and Afro-Palaearctic migrants [14,67,68,, 36, 66–69], although the reverse is seen as well [17,71,, 70–72]). It has been suggested that these patterns are a response to prevailing winds and/or availability of resources along the different routes. The choice to cross the Gulf of Mexico is likely less risky in autumn when passing cold fronts provide tailwinds, while in spring such a cold front would be a substantial obstacle and cannot be easily anticipated when setting out from the Yucatán [73]. As a result, the dominant pattern for species migrating between eastern North America and South and Central America seems to involve more frequent over-ocean flights in autumn and more individuals taking longer over-land routes around the western side of the Gulf of Mexico in spring, with an increasing tendency to circumnavigate with more westerly breeding longitudes [49, 65, 74, 75].

Species often show within population variation in migration patterns with respect to large bodies of water [14, 21, 36, 69, 74]. Individuals tracked over multiple years, often show considerable variation in route choice [21, 49, 67, 69]. What causes individuals to make different choices in different seasons remains unclear, but could relate to individual differences in physiological condition, age, resource availability at stopover sites, or local weather patterns [76,77,78,79].

Migratory stopovers appeared to be more frequent and were of longer duration in autumn than in spring. Due to low resolution for both migration timing and route, we cannot link stopover behaviour with timing or Gulf-crossing behaviour [80]. But evidence from swallows in Europe suggest that even diurnal aerial insectivores, which employ a fly-and-forage migration strategy, use stopovers before crossing major ecological barriers [81]. In autumn, more than half of whip-poor-wills appeared to stop for up to 15 days somewhere near the north coast of the Gulf of Mexico (median = 30°N). Stopovers of similar length by northbound Catharus thrushes in Columbia have been shown to allow for sufficient fat storage to fuel direct flights across both the Caribbean and the Gulf of Mexico [19]. In spring, fewer individual whip-poor-wills showed evidence of stopovers that were of sufficient length to be detected, and those that did appeared to stop further north (~37°N). In fact, all evidence of spring stopovers by males occurred in 2012, which was a much earlier spring (by the end of March, e-bird records reach 39°N in 2012 and 35°N in 2013), suggesting that whip-poor-wills may track spring phenology and adjust timing of arrival by adding or lengthening stopovers depending on the conditions they find en route. Whether these stopovers were used to accumulate fat to fuel rapid travel through inhospitable habitats (e.g., Gulf crossings), or to wait for better weather conditions, the temporal and energetic demands associated with migration may make populations exceptionally sensitive to even minor alterations in habitat quality or food abundance at these sites.

Temporal variability in the annual cycle

Across individuals, similarity in duration and variability between autumn and spring migratory timing contrasts with the expectation of greater time-constraint in pre-breeding movements [67, 82, 83]. The much larger variability in timing of departure from the wintering grounds than in arrival on the breeding grounds could largely be the result of differences in geographic spread between breeding and wintering sites (< 3° versus > 15° latitude respectively) rather than evidence of an increase in time pressure with proximity to breeding and a selective advantage to early or synchronous arrival [84, 85]. Likewise, although timing of migratory transitions have been found to be related to timing of previous events within the annual cycle for many species of migratory birds [14, 15, 21, 49], we found no evidence of any relationship suggesting either a unique lack of population-level time-limitation, or that conditions vary between individual migration routes and at different wintering sites [86, 87].

Most studies that track individuals over multiple years have found much less variation in timing than in route choice [21, 49, 67]. While we have little data to assess intra-individual differences in timing of migration, we did find that for a single individual arrival date on breeding grounds was the same in both years despite differences between years in the timing of all other transitions. Also, consistent with increasing time pressure in spring, the fastest migration rate we observed was 180 km/day in spring by a male that circumnavigated the Gulf. Still, given our expectation that migratory aerial insectivores would experience time constraints in their annual cycle, high variability in timing of migration could represent evidence of either phenotypic plasticity or genetic variation, either of which could be beneficial under a changing climate [88].

Conclusion

With increases in activity during the critical dusk and dawn periods, light-based geolocation might appear an unlikely tool for tracking movements of a crepuscular bird [44]. However, we were able to identify wintering areas, migratory routes and stopovers, and to document the variability in timing of migratory movements for a threatened nightjar population. Migratory stopovers in the southeastern and central United States and wintering locations in southern Mexico and Central America both appear important for Eastern Whip-poor-will’s at the northern edge of their range, such as those we studied in Canada. Determining the precise location of these sites, and how they are used by whip-poor-wills, will soon be possible using new technologies like archival GPS tags [89]. Ultimately, we hope protection of habitat and insect populations throughout the whip-poor-will’s range, including at migratory stopover locations, may help a higher proportion of individuals survive the pressures of long migrations and a changing climate. Regardless, our results will help to better target both research and conservation efforts for this enigmatic species.

References

Newton I. Bird migration. London: Collins; 2010.

Palacín C, Alonso JC, Martín CA, Alonso JA. Changes in bird migration patterns associated with human-induced mortality. Conserv Biol. 2017;31:106–15.

Sillett TS, Holmes RT. Variation in survivorship of a migratory songbird throughout its annual cycle. J Anim Ecol. 2002;71:296–308.

Klaassen RHG, Hake M, Strandberg R, Koks BJ, Trierweiler C, Exo K-M, et al. When and where does mortality occur in migratory birds? Direct evidence from long-term satellite tracking of raptors. J Anim Ecol. 2014;83:176–84.

Lok T, Overdijk O, Piersma T. The cost of migration: spoonbills suffer higher mortality during trans-Saharan spring migrations only. Biol Lett. 2015;11:20140944.

Smith RJ, Moore FR. Arrival fat and reproductive performance in a long-distance passerine migrant. Oecologia. 2003;134:325–31.

Newton I. Can conditions experienced during migration limit the population levels of birds? J Ornithol. 2006;147:146–66.

Drake A, Rock CA, Quinlan SP, Martin M, Green DJ. Wind speed during migration influences the survival, timing of breeding, and productivity of a Neotropical migrant, Setophaga petechia. PLoS One. 2014;9:e97152.

Latta SC, Cabezas S, Mejia DA, Paulino MM, Almonte H, Miller-Butterworth CM, et al. Carry-over effects provide linkages across the annual cycle of a Neotropical migratory bird, the Louisiana Waterthrush Parkesia motacilla. Ibis. 2016;158:395–406.

Bell CP. Seasonality and time allocation as causes of leap-frog migration in the Yellow Wagtail Motacilla flava. J Avian Biol. 1996;27:334.

Buehler DM, Piersma T. Travelling on a budget: predictions and ecological evidence for bottlenecks in the annual cycle of long-distance migrants. Philos Trans R Soc B Biol Sci. 2008;363:247–66.

Bächler E, Hahn S, Schaub M, Arlettaz R, Jenni L, Fox JW, et al. Year-round tracking of small trans-Saharan migrants using light-level geolocators. PLoS One. 2010;5:e9566.

Contina A, Bridge ES, Seavy NE, Duckles JM, Kelly JF. Using geologgers to investigate bimodal isotope patterns in Painted Buntings (Passerina ciris). Auk. 2013;130:265–72.

Lemke HW, Tarka M, Klaassen RHG, Ãkesson M, Bensch S, Hasselquist D, et al. Annual cycle and migration strategies of a trans-Saharan migratory songbird: a geolocator study in the great reed warbler. PLoS One. 2013;8:e79209.

Callo PA, Morton ES, Stutchbury BJM. Prolonged spring migration in the Red-eyed Vireo (Vireo olivaceus). Auk. 2013;130:240–6.

Jahn AE, Cueto VR, Fox JW, Husak MS, Kim DH, Landoll DV, et al. Migration timing and wintering areas of three species of flycatchers (tyrannus) breeding in the great plains of north America. Auk. 2013;130:247–57.

La Sorte FA, Fink D, Hochachka WM, Kelling S. Convergence of broad-scale migration strategies in terrestrial birds. Proc R Soc B Biol Sci. 2016;283:20152588.

Bayly NJ, Gómez C, Hobson KA, González AM, Rosenberg KV. Fall migration of the Veery (Catharus fuscescens) in northern Colombia: determining the energetic importance of a stopover site. Auk. 2012;129:449–59.

Bayly NJ, Gómez C, Hobson KA. Energy reserves stored by migrating Gray-cheeked Thrushes Catharus minimus at a spring stopover site in northern Colombia are sufficient for a long-distance flight to North America. Ibis. 2013;155:271–83.

Alerstam T. Optimal bird migration revisited. J Ornithol. 2011;152:5–23.

Stanley CQ, MacPherson M, Fraser KC, McKinnon EA, Stutchbury BJM. Repeat tracking of individual songbirds reveals consistent migration timing but flexibility in route. PLoS One. 2012;7:e40688.

Sparks TH, Yates TJ. The effect of spring temperature on the appearance dates of British butterflies 1883–1993. Ecography. 1997;20:368–74.

Brown CR, Brown MB. Intense natural selection on body size and wing and tail asymmetry in Cliff Swallows during severe weather. Evolution. 1998;52:1461–75.

Newton I. Weather-related mass-mortality events in migrants. Ibis. 2007;149:453–67.

Both C, Van Turnhout CAM, Bijlsma RG, Siepel H, Van Strien AJ, Foppen RPB. Avian population consequences of climate change are most severe for long-distance migrants in seasonal habitats. Proc R Soc B Biol Sci. 2010;277:1259–66.

Peterson TC, Zhang X, Brunet-India M, Vázquez-Aguirre JL. Changes in North American extremes derived from daily weather data. J Geophys Res Atmospheres. 2008;113:D07113.

Stokke BG, Møller AP, Sæther B-E, Rheinwald G, Gutscher H. Weather in the breeding area and during migration affects the demography of a small long-distance passerine migrant. Auk. 2005;122:637–47.

Nebel S, Mills A, McCracken JD, Taylor PD. Declines of aerial insectivores in North America follow a geographic gradient. Avian Conserv Ecol. 2010;5:1.

Smith AC, Hudson M-AR, Downes CM, Francis CM. Change points in the population trends of aerial-insectivorous birds in North America: synchronized in time across species and regions. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0130768.

Michel NL, Smith AC, Clark RG, Morrissey CA, Hobson KA. Differences in spatial synchrony and interspecific concordance inform guild-level population trends for aerial insectivorous birds. Ecography. 2016;39:774–86.

Paquette SR, Pelletier F, Garant D, Bélisle M. Severe recent decrease of adult body mass in a declining insectivorous bird population. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2014;281:20140649.

Esler D. Applying metapopulation theory to conservation of migratory birds. Conserv Biol. 2000;14:366–72.

Webster MS, Marra PP. The importance of understanding migratory connectivity and seasonal interactions. In: Greenberg R, Marra PP, editors. Birds Two Worlds Ecol Evol Migr Baltimore. Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press; 2005. p. 199–209.

Taylor CM, Norris DR. Population dynamics in migratory networks. Theor Ecol. 2010;3:65–73.

Martin TG, Chadès I, Arcese P, Marra PP, Possingham HP, Norris DR. Optimal conservation of migratory species. PLoS One. 2007;2:e751.

Hewson CM, Thorup K, Pearce-Higgins JW, Atkinson PW. Population decline is linked to migration route in the common cuckoo. Nat Commun. 2016;7:12296.

Mills AM. The influence of moonlight on the behavior of goatsuckers (Caprimulgidae). Auk. 1986;103:370–8.

Jetz W, Steffen J, Linsenmair KE. Effects of light and prey availability on nocturnal, lunar and seasonal activity of tropical nightjars. Oikos. 2003;103:627–39.

Naef-Daenzer B. An allometric function to fit leg-loop harnesses to terrestrial birds. J Avian Biol. 2007;38:404–7.

Gaunt AS, Oring LW, Able KP, Anderson DW, Baptista LF, Barlow JC, et al. Guidelines to the use of wild birds in research. Washington: The Ornithological Council; 1997.

Bridge ES, Kelly JF, Contina A, Gabrielson RM, MacCurdy RB, Winkler DW. Advances in tracking small migratory birds: a technical review of light-level geolocation. J Field Ornithol. 2013;84:121–37.

Ekstrom PA. Blue twilight in a simple atmosphere. 2002. p. 73–81.

Ekstrom PA. An advance in geolocation by light. Mem Natl Inst Polar. 2004;58:210–26.

Cresswell B, Edwards D. Geolocators reveal wintering areas of European Nightjar (Caprimulgus europaeus). Bird Study. 2013;60:77–86.

Rakhimberdiev E, Winkler DW, Bridge E, Seavy NE, Sheldon D, Piersma T, et al. A hidden Markov model for reconstructing animal paths from solar geolocation loggers using templates for light intensity. Mov Ecol. 2015;3:1–15.

Ekstrom P. Error measures for template-fit geolocation based on light. Deep Sea Res Part II Top Stud Oceanogr. 2007;54:392–403.

Lisovski S, Hewson CM, Klaassen RHG, Korner-Nievergelt F, Kristensen MW, Hahn S. Geolocation by light: accuracy and precision affected by environmental factors. Methods Ecol Evol. 2012;3:603–12.

McKinnon EA, Fraser KC, Stutchbury BJM. New discoveries in landbird migration using geolocators, and a flight plan for the future. Auk. 2013;130:211–22.

Fraser KC, Stutchbury BJM, Kramer P, Silverio C, Barrow J, Newstead D, et al. Consistent range-wide pattern in fall migration strategy of purple martin (progne subis), despite different migration routes at the gulf of Mexico. Auk. 2013;130:291–6.

Norevik G, Åkesson S, Hedenström A. Migration strategies and annual space-use in an Afro-Palaearctic aerial insectivore – the European Nightjar Caprimulgus europaeus. J. Avian Biol. 2017;in press.

R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2015.

Bell CP. Inter- and intrapopulation migration patterns. In: Greenberg R, Marra PP, editors. Birds Two worlds. Baltimore: JHU Press; 2005. p. 41–52.

Cink CL. Eastern Whip-poor-will (Antrostomus vociferus). In: Poole A, Gill F, editors. Birds N Am Online Ithaca. New York: Cornell Lab of Ornithology; 2002.

Stiles FG, Skutch AF. Guide to the birds of Costa Rica. New York: Comstock Publishing Associates, Ithaca; 1989.

Webster MS, Marra PP, Haig SM, Bensch S, Holmes RT. Links between worlds: unraveling migratory connectivity. Trends Ecol Evol. 2002;17:76–83.

Shutler D, Hussell DJT, Norris DR, Winkler DW, Robertson RJ, Bonier F, et al. Spatiotemporal patterns in nest box occupancy by tree swallows across north America. Avian Conserv Ecol. 2012;7:3.

Tøttrup AP, Thorup K. Sex-differentiated migration patterns, protandry and phenology in North European songbird populations. J Ornithol. 2007;149:161–7.

Canal D, Jovani R, Potti J. Multiple mating opportunities boost protandry in a Pied Flycatcher population. Behav Ecol Sociobiol. 2011;66:67–76.

Morbey YE, Coppack T, Pulido F. Adaptive hypotheses for protandry in arrival to breeding areas: a review of models and empirical tests. J Ornithol. 2012;153:207–15.

McKellar AE, Marra PP, Ratcliffe LM. Starting over: experimental effects of breeding delay on reproductive success in early-arriving male American redstarts. J Avian Biol. 2013;44:495–503.

Lundberg S, Alerstam T. Bird migration patterns: conditions for stable geographical population segregation. J Theor Biol. 1986;123:403–14.

McKinnon EA, Stanley CQ, Fraser KC, MacPherson MM, Casbourn G, Marra PP, et al. Estimating geolocator accuracy for a migratory songbird using live ground-truthing in tropical forest. Anim Migr. 2013;1:31–8.

Garrido OH, Kirkconnell A. Field guide to the birds of Cuba. Ithaca: Comstock Pub; 2000.

Ross JD, Bridge ES, Rozmarynowycz MJ, Bingman VP. Individual variation in migratory path and behavior among Eastern Lark Sparrows. Anim Migr. 2014;29–33.

Hobson KA, Kardynal KJ, Wilgenburg SLV, Albrecht G, Salvadori A, Cadman MD, et al. A continent-wide migratory divide in North American breeding Barn Swallows (Hirundo rustica). PLoS One. 2015;10:e0129340.

Klaassen RHG, Strandberg R, Hake M, Olofsson P, Tøttrup AP, Alerstam T. Loop migration in adult Marsh Harriers Circus aeruginosus, as revealed by satellite telemetry. J Avian Biol. 2010;41:200–7.

Vardanis Y, Klaassen RHG, Strandberg R, Alerstam T. Individuality in bird migration: routes and timing. Biol Lett. 2011;7:502–5.

Willemoes M, Strandberg R, Klaassen RHG, Tøttrup AP, Vardanis Y, Howey PW, et al. Narrow-front loop migration in a population of the common cuckoo cuculus canorus, as revealed by satellite telemetry. PLoS One. 2014;9:e83515.

Trierweiler C, Klaassen RHG, Drent RH, Exo K-M, Komdeur J, Bairlein F, et al. Migratory connectivity and population-specific migration routes in a long-distance migratory bird. Proc R Soc B Biol Sci. 2014;281:20132897.

Tøttrup AP, Klaassen RHG, Strandberg R, Thorup K, Kristensen MW, Jørgensen PS, et al. The annual cycle of a trans-equatorial Eurasian–African passerine migrant: different spatio-temporal strategies for autumn and spring migration. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2011;279:1008–16.

Schmaljohann H, Buchmann M, Fox JW, Bairlein F. Tracking migration routes and the annual cycle of a trans-Sahara songbird migrant. Behav Ecol Sociobiol. 2012;66:915–22.

Mellone U, López-López P, Limiñana R, Piasevoli G, Urios V. The trans-equatorial loop migration system of Eleonora’s falcon: differences in migration patterns between age classes, regions and seasons. J Avian Biol. 2013;44:417–26.

Rappole JH, Ramos MA. Factors affecting migratory bird routes over the Gulf of Mexico. Bird Conserv Int. 1994;4:251–62.

Fraser KC, Silverio C, Kramer P, Mickle N, Aeppli R, Stutchbury BJM. A trans-hemispheric migratory songbird does not advance spring schedules or increase migration rate in response to record-setting temperatures at breeding sites. PLoS One. 2013;8:e64587.

Stanley CQ, McKinnon EA, Fraser KC, Macpherson MP, Casbourn G, Friesen L, et al. Connectivity of Wood Thrush breeding, wintering, and migration sites based on range-wide tracking. Conserv Biol. 2015;29:164–74.

Gauthreaux SA. A radar and direct visual study of passerine spring migration in southern Louisiana. Auk. 1971;88:343–65.

Schmaljohann H, Naef-Daenzer B. Body condition and wind support initiate the shift of migratory direction and timing of nocturnal departure in a songbird. J Anim Ecol. 2011;80:1115–22.

Woodworth BK, Mitchell GW, Norris DR, Francis CM, Taylor PD. Patterns and correlates of songbird movements at an ecological barrier during autumn migration assessed using landscape- and regional-scale automated radiotelemetry. Ibis. 2015;157:326–39.

Deppe JL, Ward MP, Bolus RT, Diehl RH, Celis-Murillo A, Zenzal TJ, et al. Fat, weather, and date affect migratory songbirds’ departure decisions, routes, and time it takes to cross the Gulf of Mexico. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2015;112:E6331–8.

Alerstam T. Detours in bird migration. J Theor Biol. 2001;209:319–31.

Rubolini D, Gardiazabal Pastor A, Pilastro A, Spina F. Ecological barriers shaping fuel stores in Barn Swallows Hirundo rustica following the central and western Mediterranean flyways. J Avian Biol. 2002;33:15–22.

McNamara JM, Welham RK, Houston AI. The timing of migration within the context of an annual routine. J Avian Biol. 1998;29:416.

Conklin JR, Battley PF, Potter MA. Absolute consistency: individual versus population variation in annual-cycle schedules of a long-distance migrant bird. PLoS One. 2013;8:e54535.

Kokko H. Competition for early arrival in migratory birds. J Anim Ecol. 1999;68:940–50.

Gunnarsson TG, Gill JA, Sigurbjörnsson T, Sutherland WJ. Pair bonds: arrival synchrony in migratory birds. Nature. 2004;431:646.

Tøttrup AP, Thorup K, Rainio K, Yosef R, Lehikoinen E, Rahbek C. Avian migrants adjust migration in response to environmental conditions en route. Biol Lett. 2008;4:685–8.

Conklin JR, Battley PF, Potter MA, Fox JW. Breeding latitude drives individual schedules in a trans-hemispheric migrant bird. Nat Commun. 2010;1:67.

Nussey DH, Postma E, Gienapp P, Visser ME. Selection on heritable phenotypic plasticity in a wild bird population. Science. 2005;310:304–6.

Hallworth MT, Marra PP. Miniaturized gps tags identify non-breeding territories of a small breeding migratory songbird. Sci Rep. 2015;5:11069.

Brownrigg R, Becker RA, Wilks AR. Mapdata: Extra map databases. R package version 2.2-6. 2016.

Acknowledgements

We thank the numerous field assistants and volunteers who supported the deployment and retrieval of geolocator tags including: M Conboy, M Timpf, E Suenaga, C Freshwater, E Dobson, A Zunder, E Purves, T Willis, Z Southcott, D Okines, and M Falconer. We also appreciate the comments and suggestions of three reviewers that helped to improve the final version of this manuscript.

Funding

Funding and material support was provided by the Canadian Wildlife Service and Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry (OMNRF) Species at Risk Research and Stewardship grants (SARRFO6-10-SFU and 114-11-QUEENSU), NSERC Postgraduate Doctoral Fellowship (PAE), NSERC Discovery Grants (JJN and DJG), NSERC Early Career Researcher Supplement (JJN), the OMNRF Science and Research Branch, Environment and Climate Change Canada, and Simon Fraser University.

Availability of data and materials

The raw data analyzed during this study are available on Movebank (movebank.org, study name “Eastern whip-poor-will migrations data from English et al. 2017”) and are published in the Movebank Data Repository with DOI 10.5441/001/1.66jq0844.

Authors’ contributions

PAE, MDC and AMM conceived the idea, with contributions to study design from all authors. AMM, PAE, AEH and GJR supervised deployment of geolocators. PAE, DJG and JJN analyzed data and wrote paper. JJN and MDC provided majority of funding for equipment. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

Capture and tagging of birds followed the safety protocols of the Ornithological Council and was approved by Environment Canada (sub-permit #10759 AG) and the Simon Fraser University Animal Care Committee (protocol #1001B-11).

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional files

Additional file 1: Figure S1.

Variation in accuracy of geolocation estimates on breeding grounds as illustrated by median and interquartile ranges in latitude and longitude estimates between 15 May and 31 Jul. Black dots: locations where geolocator tags were deployed. The absolute error averaged across all sites was 1.3° for latitude and 0.56° for longitude. (PDF 55 kb)

Additional file 2: Table S1.

Non-breeding location estimates for 22 eastern whip-poor-wills breeding in Ontario, Canada. M and F in the bird ID indicates males and females. (PDF 45 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

English, P.A., Mills, A.M., Cadman, M.D. et al. Tracking the migration of a nocturnal aerial insectivore in the Americas. BMC Zool 2, 5 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40850-017-0014-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40850-017-0014-1