Abstract

Background

The Scleroderma Patient-centered Intervention Network (SPIN) developed an online self-management program (SPIN-SELF) designed to improve disease-management self-efficacy in people with systemic sclerosis (SSc, or scleroderma). The aim of this study was to evaluate feasibility aspects for conducting a full-scale randomized controlled trial (RCT) of the SPIN-SELF Program.

Methods

This feasibility trial was embedded in the SPIN Cohort and utilized the cohort multiple RCT design. In this design, at the time of cohort enrollment, cohort participants consent to be assessed for trial eligibility and randomized prior to being informed about the trial. Participants in the intervention arm are informed and provide consent, but not the control group. Forty English-speaking SPIN Cohort participants from Canada, the USA, or the UK with low disease-management self-efficacy (Self-Efficacy for Managing Chronic Disease Scale [SEMCD] score ≤ 7) who were interested in using an online self-management program were randomized (3:2 ratio) to be offered the SPIN-SELF Program or usual care for 3 months. Program usage was examined via automated usage logs. User satisfaction was assessed with semi-structured interviews. Trial personnel time requirements and implementation challenges were logged.

Results

Of 40 SPIN Cohort participants randomized, 26 were allocated to SPIN-SELF and 14 to usual care. Automated eligibility and randomization procedures via the SPIN Cohort platform functioned properly, except that two participants with SEMCD scores > 7 (scores of 7.2 and 7.3, respectively) were included, which was caused by a system programming error that rounded SEMCD scores. Of 26 SPIN Cohort participants offered the SPIN-SELF Program, only 9 (35%) consented to use the program. Usage logs showed that use of the SPIN-SELF Program was low: 2 of 9 users (22%) logged into the program only once (median = 3), and 4 of 9 (44%) accessed none or only 1 of the 9 program’s modules (median = 2).

Conclusions

The results of this study will lead to substantial changes for the planned full-scale RCT of the SPIN-SELF Program that we will incorporate into a planned additional feasibility trial with progression to a full-scale trial. These changes include transitioning to a conventional RCT design with pre-randomization consent and supplementing the online self-help with peer-facilitated videoconference-based groups to enhance engagement.

Trial registration

clinicaltrials.gov, NCT03914781. Registered 16 April 2019.

Similar content being viewed by others

Key messages regarding feasibility

-

What uncertainties existed regarding the feasibility?

An online, self-guided, self-management intervention to support self-efficacy for disease management in people with systemic sclerosis (SSc) was developed (SPIN-SELF Program). The planned full-scale randomized controlled trial (RCT) would be conducted using the novel cohort multiple RCT (cmRCT) design. In the cmRCT design, compared with conventional parallel-group RCT designs, randomization to the intervention or control arm is conducted prior to obtaining consent for the intervention, thus declining participation happens post-randomization. Uptake of the intervention offer has been low in previous studies with the cmRCT design. Thus, prior to testing for effectiveness in a full-scale RCT, we sought to (1) evaluate the offer uptake of the intervention as well as other aspects of feasibility of the planned trial methodology, and (2) assess whether the online intervention is user-friendly and acceptable to trial participants.

-

What are the key feasibility findings?

Forty participants were enrolled in the SPIN-SELF feasibility trial, and the randomization feature embedded in the Cohort platform functioned properly. Participants were able to easily connect to and use the online SPIN-SELF Program and found the program easy to use. Two key problems related to the feasibility of conducting a full-scale RCT of the SPIN-SELF Program were identified: (1) of 26 participants offered to try the SPIN-SELF Program, only 9 (35%) consented to use it, and (2) usage logs showed that use of the SPIN-SELF Program was low: 2 of 9 users (22%) logged into the program only once (median = 3), and 4 participants (44%) accessed none or only 1 of the 9 available modules in the program (median = 2).

-

What are the implications of the feasibility findings for the design of the main study?

The design of the main study needs to be adapted to improve enrollment in the SPIN-SELF Program as well as usage of the program among trial participants. Changes will include a transition from the cmRCT design to a conventional parallel-group RCT design and peer-facilitated online groups to support engagement with the SPIN-SELF Program will be organized in addition to the online self-guided program.

Background

Self-management programs are designed to support people with chronic medical conditions to improve their self-efficacy to manage their condition, maintain life roles, and cope with negative emotions. They are typically delivered in group formats and emphasize the development of problem-solving skills and effective collaboration with health care providers [1,2,3]. General and disease-specific self-management programs have been shown to improve self-efficacy for disease management, and health and quality of life outcomes (e.g., [4,5,6,7,8,9,10]), although self-guided online programs may not be effective [11]. Generic programs and programs developed for common conditions, however, do not address the unique challenges of people with rare diseases [12].

Rare diseases are defined as conditions that affect fewer than 1 in 2000 people. Cumulatively, 4–6% of people may have a rare disease [13]. Systemic sclerosis (SSc, or scleroderma) is a rare, chronic, autoimmune disease characterized by vasculopathy and excessive collagen production; it affects the skin and internal organs, including the lungs, gastrointestinal tract, and cardiovascular system [14]. Common problems include physical mobility and hand function limitations, gastrointestinal problems, fatigue, pain, sexual dysfunction, and body image distress from disfiguring changes in appearance [15, 16]. One randomized controlled trial (RCT; N = 267) tested a SSc internet-based self-management program but reported that it did not improve self-efficacy or other outcomes [17].

The Scleroderma Patient-centered Intervention Network (SPIN) is an international collaboration of researchers, clinicians, patient advocates, and people with SSc that develops, tests, and disseminates tools to support people living with SSc [18]. Patient collaborators prioritized the development of a self-management program and jointly designed the SPIN-SELF Program with SPIN investigators. It was designed as a self-guided, online intervention in order to facilitate access and dissemination of knowledge and resources in a rare disease environment, since many people with SSc do not live near specialized SSc treatment centers.

The aim of the SPIN-SELF feasibility trial was to inform necessary adjustments to the program and trial procedures prior to conducting a full-scale RCT by assessing trial procedures, required resources and management, scientific aspects, and participant acceptability of procedures and program content.

Methods

Design and setting

The SPIN-SELF Feasibility Trial was a parallel, two-arm feasibility cohort multiple RCT (cmRCT) conducted using the SPIN Cohort to identify and enroll eligible participants and ascertain outcomes. In the cmRCT design [19], participants are randomized to be offered an intervention or not based on eligibility criteria applied to their regular cohort assessments, prior to being notified about the trial. Those randomized to be offered the intervention must consent to receive it. Those not offered the intervention are not notified about the trial and only complete regular cohort measures. The trial was registered (NCT03914781), and a protocol was published [20]. Results are reported in accordance with the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) extension for randomized pilot and feasibility trials [21] and the CONSORT extension for trials using cohorts and routinely collected data [22]. There were no changes to the protocol after the trial commenced. Ethics approval for the SPIN Cohort was obtained from the Research Ethics Committee of the Centre intégré universitaire de santé et de services sociaux du Centre-Ouest-de-l'Île-de-Montréal (#MP-05-2013-150) and all participating SPIN centers. Approval for the SPIN-SELF Feasibility Trial was obtained from the Research Ethics Committee of the Centre intégré universitaire de santé et de services sociaux du Centre-Ouest-de-l’Île-de-Montréal (#2019-1146).

SPIN Cohort participants

The SPIN Cohort [18] has collected patient-reported outcomes at 3-month intervals via the internet since April 2014. Eligible participants must be classified as having SSc based on the 2013 American College of Rheumatology/ European League Against Rheumatism (ACR/EULAR) criteria [23], confirmed by a SPIN physician; ≥ 18 years old; and fluent in English, French, or Spanish. SPIN Cohort participants are recruited at 50 SPIN sites (https://www.spinsclero.com/en/cohort/sites) during regular medical visits, and written informed consent is obtained. Participants consent to (1) their data being used for observational studies; (2) their data being used to assess intervention trial eligibility and, if eligible, that they will be randomized; (3) if eligible and randomized to the intervention arm of a trial, to be contacted and offered access to the intervention; and (4) if eligible and randomized to the usual care arm of a trial, to not be notified about the trial but to use their regularly collected cohort data to evaluate trial outcomes. A medical data form is completed by the treating physician and submitted online to enroll participants. Approximately 1300-1500 active participants from 7 countries and 50 sites complete assessments in any 3-month period.

SPIN-SELF feasibility trial eligibility

Trial eligibility assessments occurred automatically via the online SPIN Cohort platform during participants’ regular SPIN Cohort assessments. Eligible participants were those who completed cohort measures in English, had low disease management self-efficacy (score ≤ 7 on the Self-Efficacy for Managing Chronic Disease Scale (SEMCD) [24]), and indicated high interest in using an online self-management intervention (≥ 6 on 0-10 scale).

Procedure: randomization, allocation concealment, consent, and blinding

We used simple randomization of participants with a 3:2 ratio to an offer to use the SPIN-SELF Program for 3 months versus usual care. A 3:2 ratio was used to attempt to enroll enough participants who would be offered the intervention to assess usage. Eligible participants were identified and randomized automatically as they completed regular SPIN Cohort assessments using a feature in the SPIN Cohort platform, which provides immediate centralized randomization and, thus, complete allocation sequence concealment.

Participants randomized to be offered the program received an automated email invitation including a link to the SPIN-SELF Program website and the consent form. At initial login, using their SPIN Cohort username and password, they were prompted to provide written consent to participate in testing the SPIN-SELF Program by verifying agreement with consent elements and providing their email address as electronic signature. Consented participants were automatically directed to the SPIN-SELF Program introduction page. Participants who logged out without consenting were returned to the consent page upon subsequent logins. Participants who accepted the offer could use the web link to enter the secure intervention site for 3 months.

SPIN personnel also contacted participants by phone, usually within 48 hours of sending the invitation email, to describe the study, review the consent form, and answer questions. A maximum of 5 attempts were made to contact participants within 10 days of sending the invitation email. If not successfully contacted, a sixth attempt was made approximately 20 days post-invite. Email and phone technical support were available to help participants with the consent process and use of the intervention site.

Participants assigned to usual care were not notified about the trial and completed their regular SPIN Cohort assessments as normal. Thus, participants offered the intervention were not blind to their status, whereas participants assigned to usual care were blind to their trial participation and assignment. This replicates actual practice, where patients are not typically advised about treatments that are not options and may reduce risk of disappointment bias [19, 25].

Intervention and comparator

The SPIN-SELF Program was designed based on key tenets of self-management skills that have been incorporated in successful self-management programs for chronic diseases, including problem solving, decision making, resource utilization, forming a patient–health care provider partnership, and taking action [26]. Input on modules, content, layout, and program navigation was obtained from focus groups with people with SSc and SPIN’s Patient Advisory Board [27].

Upon first use, instructions on how to navigate the program are provided in a website tour video. Participants are introduced to the concept of self-management by a physician with expertise in SSc and a patient sharing her experience with self-management. The program utilizes an engaging and easy-to-navigate web interface, and language of the modules is at an appropriate level for understanding based on input from members of SPIN’s Patient Advisory Board. Pages can be bookmarked, text can be enlarged, and captions for each video are available for download. There are 9 modules, and after the program introduction, users are directed to a 9-item quiz designed to guide them to modules most relevant to their symptoms and disease-management challenges. Based on the quiz score, links to the 3 most relevant modules appear on top, with links to the other 6 modules available below. The 9 modules target (1) coping with pain; (2) skin care, finger ulcers, and Raynaud’s; (3) sleep problems; (4) fatigue; (5) gastrointestinal symptoms; (6) itch; (7) managing emotions and stress; (8) coping with body image concerns due to disfigurement; and (9) effective communication with healthcare providers. Each module includes an educational component that provides background information on the topic and teaching of skills, as well as a goal-setting component.

In addition to the modules, the SPIN-SELF Program includes tools to support key self-management strategies, including education on goal setting, fillable goal-setting forms, and worksheets to help users integrate newly learned skills and techniques into daily routines. The online goal form encourages users to choose a number of days per week and total weeks to work on a goal, to reflect on why achieving the goal is important to them, and to write their reason in a text box. For each goal, users can input weekly progress, receive e-mail reminders to facilitate successful completion, and share goals and progress with friends and family. Worksheets are specifically tailored to each module and can be saved and printed for later use. The program incorporates social modeling through educational videos of people with SSc who describe their challenges and coping strategies, and of health professionals who teach key self-management techniques.

Feasibility outcomes

Feasibility outcomes included: [1] proportion of SPIN Cohort participants who met eligibility criteria [2]; functioning of automated eligibility assessment and randomization procedures [3]; proportion of eligible participants randomized to the intervention arm who consented to participate [4]; completeness of online data collection for each trial arm at 3-month follow-up [5]; completeness of intervention usage log data [6]; ability to successfully link data from the SPIN Cohort and SPIN-SELF platforms using person-level deterministic linkage with participant SPIN identification numbers [7]; personnel requirements to support consent and use of the program [8]; technological performance of the online SPIN-SELF Program; and [9] any other unanticipated challenges. Usage data provided detailed information on the number of logins, the number of modules accessed, and goals set. The data were linked to SPIN Cohort data using participants’ SPIN-ID numbers, which were used for both platforms. Study personnel tracked their activities and the time spent on an Excel spreadsheet.

To assess user acceptability and satisfaction, semi-structured interviews were conducted with consenting participants in the intervention arm, at 3 months post-randomization, using 27 items of the Patient Education Materials Assessment Tool for Audiovisual Materials (PEMAT) [28], which addresses program usability, understandability, organization, and clarity (see Appendix for the interview guide).

SPIN-SELF planned trial outcome measures

Measures of disease-management self-efficacy and functional health outcomes that will be used to evaluate the program in the full-scale trial were reported, although no hypothesis tests were conducted, consistent with the feasibility trial design [21, 29]. Outcomes were collected as part of each participant’s routine SPIN Cohort assessments 3 months post-randomization. The planned primary outcome for the SPIN-SELF full-scale trial is the SEMCD.

The 6-item SEMCD [24] measures respondent confidence to manage fatigue, pain, emotional distress, and other symptoms; to do things other than take medication to reduce illness impact; and to carry out tasks that may reduce the need to see a doctor. Items are rated on a 1 (not confident at all) to 10 (totally confident) scale. The total score is the mean of all items. The SEMCD was previously validated for SSc through the SPIN Cohort [30].

The 29-item Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS-29) profile version 2.0 [31] assesses 8 domains of health status (depression symptoms; anxiety symptoms; physical function; pain interference; fatigue; sleep disturbance; ability to participate in social roles and activities; pain intensity); there are 4 items in each of 7 domains plus a single item for pain intensity. Raw scores are converted into T-scores standardized from the general US population (mean = 50, standard deviation = 10). Higher scores indicate greater physical function and social role and activity participation but worse anxiety, depression, fatigue, sleep disturbance, pain interference, and pain intensity. The PROMIS-29 version 2.0 has been validated for SSc [32, 33].

Sample size

Guidance on the appropriate sample size for feasibility trials varies, with rules-of-thumb suggesting 12 to 30 participants or more per trial arm [34, 35]. In a previous SPIN feasibility trial of a hand exercises intervention, offer acceptance rate was approximately 60% [36]. We included a total of 40 SPIN Cohort participants with 3:2 randomization to support additional information needs from intervention arm participants.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to characterize the sample and feasibility outcomes, including personnel and time resources required, participant eligibility, recruitment numbers, percentages of participants who responded to follow-up measures, and frequency of logins and time spent using the program. The presence of floor or ceiling effects on outcome measures was assessed. Qualitative information on participant experiences was recorded.

Criteria for progression to full-scale trial

Feasibility outcomes were evaluated qualitatively, and no quantitative cut-offs for progression to full-scale trial (e.g., % consent) were pre-specified.

Results

Participant characteristics

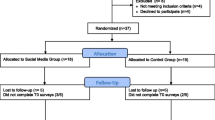

Enrollment began on July 6, 2019 and was completed on July 27, 2019. Of 40 participants, 26 (65%) were allocated to the intervention arm and 14 (35%) to the usual care arm (see Fig. 1 for SPIN Cohort participant flow through the SPIN-SELF feasibility trial). Demographic, disease characteristics, SEMCD Scale, and PROMIS-29 scores for both groups are shown in Table 1.

Feasibility outcomes

During the enrollment period, 177 SPIN Cohort participants completed cohort assessments and were evaluated for eligibility. Of these, 40 (23%) met trial eligibility criteria. One error in the automated eligibility assessment process was identified. Two enrolled participants had SEMCD scores > 7 (7.2 and 7.3) and, thus, were randomized despite not meeting eligibility criteria. This occurred because of a system programming error that rounded scores rather than including decimal places. A review of participant characteristics and assessment scores showed that all other eligible and ineligible cohort participants were correctly classified.

Total time spent by SPIN personnel on calls, including leaving voicemails, and emails with the 26 participants randomized to the intervention arm was 228 min (8.8 min per participant). Participants who attempted to log in were able to do so easily, so no troubleshooting outside of the protocol calls was needed. One participant reported difficulties using the program on their smartphone but was able to successfully use it on a computer without assistance.

Study personnel spent an additional 99 min on other tasks, including reviewing the randomization process, tracking enrollment and consent progress, and managing call logs. Mean time per day was less than 5 min. This did not include team meetings to review project progress and administration. One technical issue was identified on the first day of enrollment when intervention participants did not appear on the SPIN Cohort platform’s management page. Time spent to resolve this issue by information technology personnel was 35 min. No other challenges were reported by study personnel.

Consent and usage of the SPIN-SELF Program

Usage data from the SPIN-SELF platform and SPIN Cohort data were successfully linked 100% of the time. Of the 26 participants randomized to intervention, 15 (58%) did not log in to the consent page; 2 (8%) logged in but did not consent, and 9 (35%) consented. Of the 9 who consented, 2 (22%) logged in only once, 2 (22%) logged in twice, and the other 5 logged in 3 to 7 times (mean = 3.3; standard deviation = 2.0; median = 3).

After consent, 6 of 9 participants (67%) watched the expert introduction video, and 3 of these also watched the patient introduction (33%). Four participants (44%) used the website tour. All 9 participants completed the quiz to identify the modules most relevant to them. One participant (11%) did not access any module in the SPIN-SELF Program, and 3 participants (33%) accessed 1 of the 9 modules. Other participants accessed between 3 and 9 modules (overall mean = 2.7, standard deviation = 2.5, median = 2). Of the different modules, most participants (N = 6, 67%) accessed the fatigue module, 4 (44%) accessed the gastrointestinal symptoms module, and 3 participants (33%) accessed modules on sleep and pain. The modules addressing body image concerns, itch, and skin care were accessed by 2 participants each (22%), and the modules on effective communication with healthcare providers and managing emotions were accessed by 1 of the 9 participants (11%). Two participants (22%) created one or two goals, others did not use this feature.

Interview outcomes/user feedback

Of the 9 intervention arm participants who consented to use the program, 5 participated in post-trial interviews. Of the remaining 4 participants who were not interviewed, 2 did not respond to attempts to contact, and 2 declined to be interviewed (one reported they did not use the program enough, one indicated being unable to due to health issues). See PEMAT interview responses in Table 2. Overall, feedback of the 5 interviewed participants was very positive. The overall mean grade given by participants for the SPIN-SELF Program was 8.4/10. No concerns related to adverse events were reported.

SPIN-SELF planned trial outcome measures

Of the 40 participants, 35 (87.5%) completed their 3-month follow-up cohort assessments, including 23 in the intervention arm (88.5%) and 12 in the control arm (85.7%). Table 3 shows the SEMCD (planned primary outcome) and PROMIS-29 scores for both groups at baseline and 3-months follow-up, which are the planned trial outcome measures for the full-scale trial. The SPIN-SELF Feasibility Trial was not designed for hypothesis testing or effect size estimation, and the sample size was not appropriate to do so.

Discussion

Forty SPIN Cohort participants were successfully enrolled in the SPIN-SELF feasibility trial, and the randomization feature embedded in the Cohort platform functioned properly. However, the automated eligibility procedure allowed for two ineligible participants to be enrolled. This was caused by a system programming error that rounded down the participants’ mean scores on the SEMCD Scale. This system error will be fixed to ensure that only eligible participants are randomized for the full-scale trial. Overall, the required trial personnel resources for the trial were low and mainly spent on follow-up calls made to enrolled participants. Participants were able to easily connect to and use the program, thus required technical support was minimal. Although only 5 trial participants in the SPIN-SELF arm completed the semi-structured interview, overall, they reported high satisfaction with the trial procedures as well as the SPIN-SELF Program (average score 8.4/10). They found the program easy to use and said they would recommend it to other people with SSc. One participant suggested that there is a lot of information and would have liked more guidance on what to focus on. The satisfaction estimate should be interpreted with caution, as it might be biased and possibly overestimates satisfaction, as patients who participated in the interview might rate the program more favorably than the ones not participating. The majority of the feasibility trial participants in both arms completed the 3-months follow-up assessment (87.5%). Two major problems related to the feasibility of conducting a full-scale RCT of the SPIN-SELF Program were identified, however. These include (1) the low consent rate among participants who were offered the SPIN-SELF Program (35%) and (2) the low usage of the program among consented participants.

In the cmRCT design, compared with conventional parallel-group RCT designs, randomization to the intervention or control arm is conducted prior to obtaining consent for the intervention, thus decisions to accept or decline participation in the intervention arm happen post-randomization [22]. Although there are currently few published complete trials using the cmRCT design, the acceptance rate of the intervention offered in published trials has consistently been low (40-50%) [22, 37, 38]. This was also the case in a recently completed trial of SPIN’s online hand exercises program (N = 466; consent rate 61%), which similarly enrolled participants through the SPIN Cohort [39]. Although the uptake of the SPIN-HAND Program was somewhat higher than previously published studies and the present feasibility trial (35%), the percentage of participants with uptake of the intervention offer in other trials using the cmRCT design appears to be problematic generally. When the cmRCT design was introduced in 2010, it was suggested that cohort participants, in addition to assessing eligibility based on the presence of symptoms or problems, could be presented with a list of possible interventions, as part of regular cohort data collection. These so-called signaling items assess if they would agree to use an intervention if offered, as we did in the current feasibility trial. The results of the present study and our previous SPIN-HAND trial [39] suggest that, despite selecting patients based on their indicated interest in the cohort’s signaling item, uptake of the offer to try interventions and use among consenters remains low. In intention-to-treat (ITT) analyses, patients who do not accept the offer to try the SPIN-SELF Program are included in the intervention arm. This allows estimation of the effects associated with offering the intervention but does not provide an estimate of the effects among people who are interested in using the intervention, which may be the main effect of interest for some stakeholders [19, 40]. SPIN works with patient organizations to disseminate interventions post-trials, free-of-charge, via their websites, and they are interested in effects among people seeking such opportunities. While estimates of effectiveness among consenters could be improved by statistical approaches such as a complier average causal effect (CACE) analysis [41], this approach would not account for the low usage of the intervention.

We plan to make two major changes to the design of the planned SPIN-SELF Trial, which we will test in an additional feasibility trial with progression to a full-scale trial. First, rather than utilizing the cmRCT design, we will conduct a conventional parallel-groups RCT, utilizing the SPIN Cohort as well as external enrollment procedures to enroll participants. Thus, eligible SPIN Cohort participants, based on their regular assessments, will be contacted and asked to consent to participate in the SPIN-SELF Trial prior to enrollment and randomization. We will additionally increase our recruitment efforts by advertising the trial through social media (Twitter and Facebook) posts to generate interest in the trial from both SPIN Cohort and non-Cohort individuals with SSc.

Second, we will move from an individual self-guided program to a group-based program in which participants use the online SPIN-SELF Program as the curriculum in an interactive program. Low usage of self-guided, online psychological programs, as we encountered in our study, is a well-known problem across settings [42, 43]. While the optimal format and dose of guidance have not been established, there are indications that adding some form of guidance to online interventions improves usage attrition [44, 45]. Various models have been utilized for delivering self-management interventions, including in-person peer-led groups, such as in the Chronic Disease Self-management Program [3] and the Arthritis Self-management Program [46]. An online version of the Chronic Disease Self-management Program, which included email facilitation by peers, had a high level of participation (N = 249; 92% logged in at least once; mean logins 25.4, SD 1.7) [47]. Recently, SPIN conducted a trial of the COVID-19 Home-isolation Activities Together (SPIN-CHAT) Program during the first wave of COVID-19 (N = 172) [48, 49]. SPIN-CHAT was a 4-week (3 sessions per week) videoconference-based group intervention that provided (a) education and practice with mental health coping strategies and (b) social support to reduce isolation. Of the 86 participants allocated to an intervention group, 75 attended at least one session, and 66 (77%) attended at least 8 sessions. In addition to SPIN-CHAT, SPIN has also used videoconference-based intervention delivery successfully in an almost complete trial of a training program for peer support group leaders [50]. Thus, to address the low uptake of the SPIN-SELF Program, we will add peer-facilitated videoconference-based groups in the full-scale trial, where 8–10 people with SSc will be provided with a directed and interactive experience to support their use of the online SPIN-SELF Program. Intervention groups will be facilitated by trained peer support group leaders to be potentially scalable and because of patient preference for peer support.

The present study has limitations that should be considered in interpreting its results. First, the SPIN Cohort constitutes a convenience sample of SSc patients receiving treatment at a SPIN recruiting center, and patients at these centers may differ from those in other settings. Additionally, SSc patients in the SPIN Cohort complete questionnaires online, which may further limit the generalizability of findings, as all participants already have Internet access and are comfortable using it in a research setting. Third, we were only able to include English-speaking SPIN Cohort participants in this study. French-speaking patients were not included because there was a limited number of French-speaking SPIN Cohort participants at the start of this study, and we wanted to be able to assess feasibility aspects but be able to maximize the number of French participants eligible for the subsequent full-scale trial. At this moment, the SPIN-SELF Program is not yet available in Spanish, meaning we cannot include Spanish-speaking Cohort patients in the trial. Finally, we did not attempt to assess the reasons for not accessing the intervention in non-consenting participants, which might have given us additional insights into reasons for the low uptake.

In sum, the SPIN-SELF feasibility trial identified major problems, including low uptake of the intervention offer among participants randomized to intervention and low usage among those who did consent to try the intervention. This will lead to substantial changes that we will incorporate into a planned additional feasibility trial with progression to a full-scale trial. These changes include a transition from the cmRCT design to a conventional RCT design and a change in the mode of delivery to include additional peer-facilitated videoconference-based groups to the online program. The full-scale RCT will provide information on effectiveness of the SPIN-SELF Program. After the trial, it will be made available through patient organizations around the world to support people in their efforts to cope with living with SSc.

Availability of data and materials

All data extracted and analyzed for the present study are available from the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

- SPIN:

-

Scleroderma Patient-centered Intervention Network

- SSc:

-

Systemic sclerosis

- SPIN-SELF:

-

Scleroderma Patient-centered Intervention Network Self-management Program

- RCT:

-

Randomized controlled trial

- SEMCD:

-

Self-Efficacy for Managing Chronic Disease Scale SEMCD

- cmRCT:

-

Cohort multiple RCT

- CONSORT:

-

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials

- ACR:

-

American College of Rheumatology

- EULAR:

-

European League Against Rheumatism

- PEMAT:

-

Patient Education Materials Assessment Tool for Audiovisual Materials

- PROMIS-29:

-

Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System

- ITT:

-

Intention-to-treat

- CACE:

-

Complier average causal effect

References

Lorig K, Mazonson P, Holman H. Evidence suggesting that health education for self-management in patients with chronic arthritis has sustained health benefits while reducing health care costs. Arthritis Rheum. 1993;36:439–46.

Lorig K, Lubeck D, Kraines R, Seleznick M, Holman H. Outcomes of self-help education for patients with arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1985;28:680–5.

Lorig K, Sobel DS, Ritter PL, Laurent D, Hobbs M. Effect of a self-management program on patients with chronic disease. Eff Clin Pract. 2001;4:256–62.

Brady TJ, Murphy L, O’Colmain BJ, Beauchesne D, Daniels B, Greenberg M, et al. A meta-analysis of health status, health behaviors, and health care utilization outcomes of the chronic disease self-management program. Prev Chronic Dis. 2013;10:120112.

Sakakibara BM, Kim AJ, Eng JJ. A systematic review and meta-analysis on self-management for improving risk factor control in stroke patients. Int J Behav Med. 2017;24:42–53.

Zimbudzi E, Lo C, Misso ML, Ranasinha S, Kerr PG, Teede HJ, et al. Effectiveness of self-management support interventions for people with comorbid diabetes and chronic kidney disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Syst Rev. 2018;7:84.

Zhao Q, Chen C, Zhang J, Ye Y, Fan X. Effects of self-management interventions on heart failure: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Int J Nurs Stud. 2020;110:103689.

Captieux M, Pearce G, Parke HL, Epiphaniou E, Wild S, Taylor SJC, et al. Supported self-management for people with type 2 diabetes: a meta-review of quantitative systematic reviews. BMJ Open. 2018;8:e024262.

Jonkman NH, Westland H, Groenwold RH, Ågren S, Atienza F, Blue L, et al. Do self-management interventions work in patients with heart failure? An individual patient data meta-analysis. Circulation. 2016;133:1189–98.

Hodkinson A, Bower P, Grigoroglou C, Zghebi SS, Pinnock H, Kontopantelis E, et al. Self-management interventions to reduce healthcare use and improve quality of life among patients with asthma: systematic review and network meta-analysis. BMJ. 2020;370:m2521.

Shaw G, Whelan M, Armitage L, Roberts N, Farmer A. Are COPD self-management mobile applications effective? A systematic review and meta-analysis. NPJ Prim Care Respir Med. 2020;30:1–10.

Milette K, Thombs BD, Maiorino K, Nielson WR, Körner A, Peláez S. Challenges and strategies for coping with scleroderma: implications for a scleroderma-specific self-management program. Disabil Rehabil. 2019;41:2506–15.

Wakap SN, Lambert DM, Olry A, Rodwell C, Gueydan C, Lanneau V, et al. Estimating cumulative point prevalence of rare diseases: analysis of the Orphanet database. Eur J Hum Genet. 2020;28:165–73.

Allanore Y, Simms R, Distler O, Trojanowska M, Pope J, Denton CP, et al. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2015;1:1–21.

Bassel M, Hudson M, Taillefer SS, Schieir O, Baron M, Thombs BD. Frequency and impact of symptoms experienced by patients with systemic sclerosis: results from a Canadian National Survey. Rheumatology. 2011;50:762–7.

Thombs BD, van Lankveld W, Bassel M, Baron M, Buzza R, Haslam S, et al. Psychological health and well-being in systemic sclerosis: state of the science and consensus research agenda. Arthritis Care Res. 2010;62:1181–9.

Khanna D, Serrano J, Berrocal VJ, Silver RM, Cuencas P, Newbill SL, et al. Randomized controlled trial to evaluate an internet-based self-management program in systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Care Res. 2019;71:435–47.

Kwakkenbos L, Jewett LR, Baron M, Bartlett SJ, Furst D, Gottesman K, et al. The scleroderma patient-centered intervention network (SPIN) cohort: protocol for a cohort multiple randomized controlled trial (cmRCT) design to support trials of psychosocial and rehabilitation interventions in a rare disease context. BMJ Open. 2013;3. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen.

Relton C, Torgerson D, O’Cathain A, Nicholl J. Rethinking pragmatic randomized controlled trials: introducing the “cohort multiple randomized controlled trial” design. BMJ. 2010;340:c1066.

Carrier M, Kwakkenbos L, Nielson WR, Fedoruk C, Nielsen K, Milette K, et al. The scleroderma patient-centered intervention network self-management program: protocol for a randomized feasibility trial. JMIR Res Protoc. 2020;9:e16799.

Chan CL, Campbell MJ, Bond CM, Hopewell S, Thabane L, et al. CONSORT 2010 statement: extension to randomized pilot and feasibility trials. BMJ. 2016;355:i5239.

Kwakkenbos L, Imran M, McCall S, Mc Cord K, Fröbert O, Hemkens LG, et al. CONSORT extension for the reporting of randomized controlled trials conducted using cohorts and routinely collected data (CONSORT-ROUTINE): checklist with explanation and elaboration. BMJ. (in press).

Van Den Hoogen F, Khanna D, Fransen J, Johnson SR, Baron M, Tyndall A, et al. 2013 classification criteria for systemic sclerosis: an American College of Rheumatology/European league against rheumatism collaborative initiative. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65:2737–47.

Ritter PL, Lorig K. The English and Spanish self-efficacy to manage chronic disease scale measures were validated using multiple studies. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014;67:1265–73.

Zwarenstein M, Treweek S, Gagnier JJ, Altman DG, Tunis S, Haynes B, et al. Improving the reporting of pragmatic trials: an extension of the CONSORT statement. BMJ. 2008;337:a2390.

Lorig KR, Holman HR. Self-management education: history, definition, outcomes, and mechanisms. Ann Behav Med. 2003;26:1–7.

Patient Advisory Board. Available at: https://www.spinsclero.com/en/Team?teamID=f120d6a6-8bee-62ed-b515-ff0000ce1efe. Accessed 22 Nov 2020.

Shoemaker SJ, Wolf MS, Brach C. Development of the patient education materials assessment tool (PEMAT): a new measure of understandability and actionability for print and audiovisual patient information. Patient Educ Couns. 2014;96:395–403.

Kraemer HC, Mintz J, Noda A, Tinklenberg J, Yesavage JA. Caution regarding the use of pilot studies to guide power calculations for study proposals. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63:484–9.

Riehm KE, Kwakkenbos L, Carrier M, Bartlett SJ, Malcarne VL, Mouthon L, et al. Validation of the self-efficacy for managing chronic disease scale: a scleroderma patient-centered intervention network cohort study. Arthritis Care Res. 2016;68:1195–200.

Hays RD, Spritzer KL, Schalet BD, Cella D. PROMIS®-29 v2. 0 profile physical and mental health summary scores. Qual Life Res. 2018;27:1885–91.

Kwakkenbos L, Thombs BD, Khanna D, Carrier M, Baron M, Furst DE, et al. Performance of the patient-reported outcomes measurement information System-29 in scleroderma: a scleroderma patient-centered intervention network cohort study. Rheumatology. 2017;56:1302–11.

Hinchcliff M, Beaumont JL, Thavarajah K, Varga J, Chung A, Podlusky S, et al. Validity of two new patient-reported outcome measures in systemic sclerosis: patient-reported outcomes measurement information system 29-item health profile and functional assessment of chronic illness therapy–dyspnea short form. Arthritis Care Res. 2011;63:1620–8.

Sim J, Lewis M. The size of a pilot study for a clinical trial should be calculated in relation to considerations of precision and efficiency. J Clin Epidemiol. 2012;65:301–8.

Julious SA. Sample size of 12 per group rule of thumb for a pilot study. Pharm Stat. 2005;4:287–91.

Carrier M, Kwakkenbos L, Boutron I, Welling J, Sauve M, van den Ende C, et al. Randomized feasibility trial of the scleroderma patient-centered intervention network hand exercise program (SPIN-HAND): study protocol. J Scleroderma Relat Disord. 2018;3:91–7.

Viksveen P, Relton C, Nicholl J. Depressed patients treated by homeopaths: a randomized controlled trial using the “cohort multiple randomized controlled trial”(cmRCT) design. Trials. 2017;18:299.

Reeves D, Howells K, Sidaway M, Blakemore A, Hann M, Panagioti M, et al. The cohort multiple randomized controlled trial design was found to be highly susceptible to low statistical power and internal validity biases. J Clin Epidemiol. 2018;95:111–9.

Scleroderma Patient-centered Intervention Network (SPIN) Hand Program (SPIN-HAND). NCT03419208. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03419208?term=spin-hand&draw=2&rank=1. Accessed 19 Mar 2021.

McCoy CE. Understanding the intention-to-treat principle in randomized controlled trials. West J Emerg Med. 2017;18:1075–8.

Pate A, Candlish J, Sperrin M, Van Staa TP. Cohort multiple randomized controlled trials (cmRCT) design: efficient but biased?. A simulation study to evaluate the feasibility of the cluster cmRCT design. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2016;16:109.

Batterham PJ, Calear AL. Preferences for internet-based mental health interventions in an adult online sample: findings from an online community survey. JMIR Ment Health. 2017;4:e26.

Musiat P, Goldstone P, Tarrier N. Understanding the acceptability of e-mental health-attitudes and expectations towards computerised self-help treatments for mental health problems. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14:109.

Baumeister H, Reichler L, Munzinger M, Lin J. The impact of guidance on internet-based mental health interventions — a systematic review. Internet Interv. 2014;1:205–15.

Shim M, Mahaffey B, Bleidistel M, Gonzalez A. A scoping review of human-support factors in the context of internet-based psychological interventions (IPIs) for depression and anxiety disorders. Clin Psychol Rev. 2017;57:129–40.

Lorig K, Holman H. Arthritis self-management studies: a twelve-year review. Health Educ Q. 1993;20:17–28.

Lorig K, Ritter PL, Plant K, Laurent DD, Kelly P, Rowe S. The South Australia health chronic disease self-management internet trial. Health Educ Behav. 2013;40:67–77.

Thombs BD, Kwakkenbos L, Carrier ME, et al. Protocol for a partially nested randomized controlled trial to evaluate the effectiveness of the scleroderma patient-centered intervention network COVID-19 home-isolation activities together (SPIN-CHAT) program to reduce anxiety among at-risk scleroderma patients. J Psychosom Res. 2020;135:110132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2020.110132.

Thombs BD, Kwakkenbos L, Levis B, Bourgeault A, Henry RS, Levis AW, et al. Effects of a multi-faceted education and support program on anxiety symptoms among people with systemic sclerosis with at least mild anxiety during COVID-19: a two-arm parallel partially nested randomised controlled trial. Lancet Rheumatol. In press.

Thombs BD, Aguila K, Dyas L, Carrier M, Fedoruk C, Horwood L, et al. Protocol for a partially nested randomized controlled trial to evaluate the effectiveness of the scleroderma patient-centered intervention network support group leader EDucation (SPIN-SSLED) program. Trials. 2019;20:717.

Acknowledgements

The SPIN-SELF Program was made possible thanks to the hard work and dedication of SPIN Patient Advisory Board members including Catherine Fortuné, Ottawa Scleroderma Support Group, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada; Dominique Godard, Association des Sclérodermiques de France, Sorel-Moussel, France; Karen Gottesman, Scleroderma Foundation, Los Angeles, California, USA; Geneviève Guillot, Sclérodermie Québec, Montreal, Quebec, Canada; Catarina Leite, University of Minho, Braga, Portugal; Karen Nielsen, Scleroderma Society of Ontario, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada; Maureen Sauvé, Scleroderma Society of Ontario, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada; and Joep Welling, NVLE Dutch patient organization for systemic autoimmune diseases, Utrecht, The Netherlands.

The SPIN Investigators include:

Laura K. Hummers, Department of Rheumatology, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland, USA; Robert Riggs, Scleroderma Foundation, Danvers, Massachusetts, USA; Shervin Assassi, University of Texas McGovern School of Medicine, Houston, Texas, USA; Ghassan El-Baalbaki, Université du Québec à Montréal, Montreal, Quebec, Canada; Carolyn Ells, McGill University, Montreal, Quebec, Canada; Kim Fligelstone, Scleroderma & Raynaud’s UK, London, UK; Amy Gietzen, Scleroderma Foundation, Tri-State Chapter, Binghamton, New York, USA; Geneviève Guillot, Sclérodermie Quebec, Longueuil, Quebec, Canada; Daphna Harel, New York University, New York, New York, USA; Monique Hinchcliff, Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, Connecticut, USA; Christelle Nguyen, Université Paris Descartes, Université de Paris, Paris, France; François Rannou, Université Paris Descartes, Université de Paris, Paris, France, and Assistance Publique - Hôpitaux de Paris, Paris, France; Karen Nielsen, Scleroderma Society of Ontario, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada; Michelle Richard, Scleroderma Atlantic, Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada; Anne A. Schouffoer, Leiden University Medical Center, Leiden, The Netherlands; Christian Agard, Centre Hospitalier Universitaire - Hôtel-Dieu de Nantes, Nantes, France; Nassim Ait Abdallah, Assistance Publique - Hôpitaux de Paris, Hôpital St-Louis, Paris, France; Alexandra Albert, CHU de Québec - Université Laval, Quebec, Quebec, Canada; Marc André, Centre Hospitalier Universitaire Gabriel-Montpied, Clermont-Ferrand, France; Elana J. Bernstein, Columbia University, New York, New York, USA; Sabine Berthier, Centre Hospitalier Universitaire Dijon Bourgogne, Dijon, France; Lyne Bissonnette, Université de Sherbrooke, Sherbrooke, Quebec, Canada; Alessandra Bruns, Université de Sherbrooke, Sherbrooke, Quebec, Canada; Patricia Carreira, Servicio de Reumatologia del Hospital 12 de Octubre, Madrid, Spain; Marion Casadevall, Assistance Publique - Hôpitaux de Paris, Hôpital Cochin, Paris, France; Benjamin Chaigne, Assistance Publique - Hôpitaux de Paris, Hôpital Cochin, Paris, France; Chase Correia, Northwestern University, Chicago, Illinois, USA; Benjamin Crichi, Assistance Publique - Hôpitaux de Paris, Hôpital St-Louis, Paris, France; Robyn Domsic, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, USA; James V. Dunne, St. Paul's Hospital and University of British Columbia, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada; Bertrand Dunogue, Assistance Publique - Hôpitaux de Paris, Hôpital Cochin, Paris, France; Regina Fare, Servicio de Reumatologia del Hospital 12 de Octubre, Madrid, Spain; Dominique Farge-Bancel, Assistance Publique - Hôpitaux de Paris, Hôpital St-Louis, Paris, France; Paul R. Fortin, CHU de Québec - Université Laval, Quebec, Quebec, Canada; Brigitte Granel-Rey, Aix Marseille Université, and Assistance Publique - Hôpitaux de Marseille, Hôpital Nord, Marseille, France; Genevieve Gyger, Jewish General Hospital and McGill University, Montreal, Quebec, Canada; Eric Hachulla, Centre Hospitalier Régional Universitaire de Lille, Hôpital Claude Huriez, Lille, France; Ariane L Herrick, University of Manchester, Salford Royal NHS Foundation Trust, Manchester, UK; Sabrina Hoa, Centre hospitalier de l’Université de Montréal – CHUM, Montreal, Quebec, Canada; Alena Ikic, CHU de Québec - Université Laval, Quebec, Quebec, Canada; Niall Jones, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada; Nader Khalidi, McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada; Marc Lambert, Centre Hospitalier Régional Universitaire de Lille, Hôpital Claude Huriez, Lille, France; David Launay, Centre Hospitalier Régional Universitaire de Lille, Hôpital Claude Huriez, Lille, France; Hélène Maillard, Centre Hospitalier Régional Universitaire de Lille, Hôpital Claude Huriez, Lille, France; Nancy Maltez, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada; Joanne Manning, Salford Royal NHS Foundation Trust, Salford, UK; Isabelle Marie, CHU Rouen, Hôpital de Bois-Guillaume, Rouen, France; Maria Martin, Servicio de Reumatologia del Hospital 12 de Octubre, Madrid, Spain; Thierry Martin, Les Hôpitaux Universitaires de Strasbourg, Nouvel Hôpital Civil, Strasbourg, France; Ariel Masetto, Université de Sherbrooke, Sherbrooke, Quebec, Canada; François Maurier, Uneos - Groupe hospitalier associatif, Metz, France; Arsene Mekinian, Assistance Publique - Hôpitaux de Paris, Hôpital St-Antoine, Paris, France; Sheila Melchor, Servicio de Reumatologia del Hospital 12 de Octubre, Madrid, Spain; Mandana Nikpour, St Vincent’s Hospital and University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia; Louis Olagne, Centre Hospitalier Universitaire Gabriel-Montpied, Clermont-Ferrand, France; Vincent Poindron, Les Hôpitaux Universitaires de Strasbourg, Nouvel Hôpital Civil, Strasbourg, France; Susanna Proudman, Royal Adelaide Hospital and University of Adelaide, Adelaide, South Australia, Australia; Alexis Régent, Assistance Publique - Hôpitaux de Paris, Hôpital Cochin, Paris, France; Sébastien Rivière, Assistance Publique - Hôpitaux de Paris, Hôpital St-Antoine, Paris, France; David Robinson, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada; Esther Rodriguez, Servicio de Reumatologia del Hospital 12 de Octubre, Madrid, Spain; Sophie Roux, Université de Sherbrooke, Sherbrooke, Quebec, Canada; Perrine Smets, Centre Hospitalier Universitaire Gabriel-Montpied, Clermont-Ferrand, France; Vincent Sobanski, Centre Hospitalier Régional Universitaire de Lille, Hôpital Claude Huriez, Lille, France; Robert Spiera, Hospital for Special Surgery, New York City, New York, USA; Virginia Steen, Georgetown University, Washington, DC, USA; Evelyn Sutton, Dalhousie University, Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada; Carter Thorne, Southlake Regional Health Centre, Newmarket, Ontario, Canada; Pearce Wilcox, St. Paul's Hospital and University of British Columbia, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada; Angelica Bourgeault, Jewish General Hospital, Montreal, Quebec, Canada; Mara Cañedo Ayala, Jewish General Hospital, Montreal, Quebec, Canada; Andrea Carboni Jiménez, Jewish General Hospital, Montreal, Quebec, Canada; Marie-Nicole Discepola, Jewish General Hospital, Montreal, Quebec, Canada; Maria Gagarine, Jewish General Hospital, Montreal, Quebec, Canada; Julia Nordlund, Jewish General Hospital, Montreal, Quebec, Canada.

Funding

Funding for the SPIN-SELF Feasibility Trial was provided by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (TR3-119192; PJT-148504). In addition, SPIN has received funding for its core activities, including the SPIN Cohort, from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Arthritis Society, the Lady Davis Institute for Medical Research of the Jewish General Hospital, Montreal, Canada, the Jewish General Hospital Foundation, Montreal, Canada, McGill University, Montreal, Canada, the Scleroderma Society of Ontario, Scleroderma Canada, Sclérodermie Québec, Scleroderma Manitoba, Scleroderma Atlantic, the Scleroderma Association of BC, Scleroderma SASK, Scleroderma Australia, Scleroderma New South Wales, Scleroderma Victoria, and Scleroderma Queensland. Dr. Levis was supported by a Fonds de recherche du Québec - Santé Postdoctoral Training Fellowship. Dr. Johnson is supported by the Gurmej Kaur Dhanda Scleroderma Research Award, and then Scleroderma Association of British Columbia. Dr. Thombs was supported by a Tier 1 Canada Research Chair. Funders of the SPIN-SELF feasibility trial had no role in the study design, and/or writing and publishing decisions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

LK, MEC, WRN, MS, SJB, VLM, MDM, IB, LM, and BDT were responsible for the study conception and design. LK, MEC, WRN, CF, BL, JP, TF, SG, SRJ, PP, LJ, JG, LC, DB, KAT, JC, JW, CF, CL, KG, MS, TSRR, MH, ML, MESA, SJB, VLM, MDM, LM, and BDT contributed to content development. JP, TF, SRJ, JG, LC, TSRR, MH, ML, MDM, and LM were involved in recruitment for the SPIN Cohort. LK, MEC, CF, RSH, LT, KAT, JC, WvB, AB and BDT, were responsible for implementation of the trial or acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of trial data. LK, NØ and BDT were responsible for drafting the manuscript. All authors provided a critical review and approved the final manuscript. BDT is the guarantor.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The SPIN Cohort study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Jewish General Hospital, Montréal, Canada (number MP-05-2013-150) and by the research ethics committees of each participating centre. Ethics approval for the SPIN-SELF Feasibility Trial was obtained from the Research Ethics Committee of the Jewish General Hospital, Montreal, Canada (number 2019-1146).

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

All authors have completed the ICJME uniform disclosure form. Dr. Mouthon reported personal fees from Actelion/Johnson & Johnson, grants from LFB, non-financial support from Octapharma, and non-financial support from Grifols, all outside the submitted work. Dr. Bartlett is a member of the Board of the Directors of the PROMIS Health Organization. All other authors declare: no support from any organization for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organizations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years. All authors declare no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

SPIN-SELF Program participant interviews

Process

1. Did the initial invitation email provide you with the information you needed to understand how to sign up for the study?

Yes. No.

If No: What information was missing?

2. Did you find the follow-up telephone call you received within 48 hours of the invitation email to be helpful?

Yes. No.

If No: Why not?

Purpose

3. Did you understand the objective of the SPIN-SELF program?

Yes. No.

If No: How could the objective be clarified?

4. Did you find the information provided in the SPIN-SELF program relevant to you?

Yes. No.

If No: How could the information provided be made more relevant to you or other scleroderma patients?

Words and language

5. Did you find that the program used common, everyday language that was easy to understand?

Yes. No.

If No: Can you give an example of concept(s) or word(s) that you did not understand?

6. Did you understand all the medical terms or, if not, were they clearly explained in the SPIN-SELF program?

Yes. No.

If No: Can you give an example of medical term(s) that you did not understand?

Content, organization, navigation

7. Did you find that the SPIN-SELF program was broken down into manageable chunks or sections?

Yes. No.

If No: Which parts of the content weren’t broken down into manageable chunks or sections and how could we improve them?

8. Did you find the different pages or sections of the program clearly labelled?

Yes. No.

If No: What section(s) could be more clearly labeled?

9. Did you find it easy to navigate through the intervention and to understand where to go next?

Yes. No.

If No: How could the different steps to navigate the intervention be more clearly explained?

10. Did you consult the “More info” tab (Scleroderma 101, Patient Stories)?

Yes. No.

If No: Why not?

11. Did you experience any technical difficulties while using the program?

Yes. No.

If Yes: What type of technical problems? Did you request assistance from the SPIN team? If you did, was the SPIN team able to help you resolve them?

12. Did you use the website tour?

Yes. No.

If Yes: Was it helpful to learn to navigate the website? Why or why not?

13. Did you use the “My Bookmarks” feature?

Yes. No.

If Yes: Did you find it helpful for easily navigating to the pages you wanted? Why or why not?

Learning aids

14. Did the fact that the program was introduced by scleroderma experts and patients make the program more credible and relatable?

Why or why not?

15. Did you understand how to correctly use the techniques explained in the modules?

Yes. No.

If No: What would have helped you better understand how to correctly perform the techniques?

16. Were you able to clearly understand the people speaking in the videos?

Yes. No.

If No: Why couldn’t you understand the words in the videos? (e.g. too fast, too soft, mumbling, accent)? Are there any videos in particular that were more difficult to understand than others? If yes, which one(s)?

17. Did you look at the video transcripts?

Yes. No.

If Yes: Were the video transcripts helpful to you? Why or why not?

Actionability (worksheets, goal-setting, motivation)

18. Did you use the worksheets?

Yes. No.

If No: Why not? What could have been a better tool?

19. Did you set goals for yourself using the “My Goals” feature?

Yes. No.

Why or why not?

20. Did you use the option to share your goals with friends and family via email?

Yes. No.

If Yes: Did the option to share your goals with friends and family via email help you stick with your goals? Yes. No.

If No: What other motivational feature(s) might have been more helpful?

21. Did you incorporate the tools and techniques you learned into your planned routine and stick with it?

Yes. No.

If No: What were some obstacles you faced when trying to incorporate the tools and techniques into your routine? How could the SPIN-SELF program have helped you to overcome these obstacles?

22. Did you use the feature to track your progress?

Yes. No.

If Yes: Did having the option to track your progress week after week encourage you to continue performing the techniques? Yes. No.

If No: Why not? Did you use any other way to track your progress? If so, what did you do?

23. Did you set email reminders for yourself?

Yes. No.

If Yes: Did having the option set email reminders for yourself help you incorporate the techniques into your routine? Yes. No.

If No: Did you use another type of reminder?

Overall evaluation

24. How user-friendly on a 0–10 scale (0, being the worst and 10 being the best possible score) would you rate the SPIN-SELF program?

25. Would you recommend this program to someone with scleroderma?

Yes. No.

If no, why?

26. What grade (on a 0-10 scale, 0 being the worst and 10 being the best possible score) would you give the program?

0 (worst) to 10 (best).

27. Is there anything you want to give us feedback about that was not included in this interview?

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Kwakkenbos, L., Østbø, N., Carrier, ME. et al. Randomized feasibility trial of the Scleroderma Patient-centered Intervention Network Self-Management (SPIN-SELF) Program. Pilot Feasibility Stud 8, 45 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40814-022-00994-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40814-022-00994-5