Abstract

Background

Participation in ultra-endurance races may lead to a transient decline in cardiac function and increased cardiovascular biomarkers. This study aims to assess alterations in biventricular function immediately and five days after the competition in relation to elevation of high-sensitivity cardiac Troponin I (hs-cTnI) and N-terminal-pro-brain-natriuretic-peptide (NT-proBNP).

Methods and Results

Fifteen participants of an ultramarathon (UM) with a running distance of 130 km were included. Transthoracic echocardiography and quantification of biomarkers was performed before, immediately after and five days after the race. A significant reduction in right ventricular fractional area change (FAC) was observed after the race (48.0 ± 4.6% vs. 46.7 ± 3.8%, p = 0.011) that persisted five days later (48.0 ± 4.6% vs. 46.3 ± 3.9%, p = 0.027). No difference in left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) was found (p = 0.510). Upon stratification according to biomarkers, participants with NT-proBNP above the median had a significantly reduced LVEF directly (60.8 ± 3.6% vs. 56.9 ± 4.8%, p = 0.030) and five days after the race (60.8 ± 3.6% vs. 55.3 ± 4.5%, p = 0.007) compared to baseline values. FAC was significantly reduced five days after the race (48.4 ± 5.1 vs. 44.3 ± 3.9, p = 0.044). Athletes with hs-cTnI above the median had a significantly reduced FAC directly after the race (48.1 ± 4.6 vs. 46.5 ± 4.4, p = 0.038), while no difference in LVEF was observed. No alteration in cardiac function was observed if hs-cTnI or NT-proBNP was below the median.

Conclusion

A slight decline in cardiac function after prolonged strenuous exercise was observed in athletes with an elevation of hs-cTnI and NT-proBNP above the median but not below.

Key Findings

-

Participation in an ultra-endurance marathon with a running distance of 130 km is associated with a transient decline in cardiac function in those athletes with markedly increased N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide and high-sensitivity cardiac troponin I after the race.

-

This alteration in cardiac function is not found in athletes with only a minor elevation of these biomarkers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Physical activity with low to moderate intensity is associated with reduced cardiovascular morbidity and overall mortality [1, 2]. By contrast, ultra-endurance races such as ultra-marathons (UM) with a running duration of substantially more than 42 kms (km) are associated with potential adverse effects on cardiac function [3,4,5]. Previous studies suggest that ultra-endurance competitions might be associated with a transient alteration of right (RV) and left ventricular (LV) function, including an increase in RV size and biventricular systolic dysfunction after the race [3, 4]. In addition, increased biomarkers indicative of myocyte necrosis, cardiac congestion and inflammation are reported in participants of ultra-endurance events [6, 7]. However, elevation of markers of cardiovascular stress, including high-sensitivity cardiac troponin I (hs-cTnI) and N-terminal-pro-brain-natriuretic-peptide (NT-proBNP), is only detected in some participants, potentially identifying individuals with significant changes of cardiac function during and after the race [6, 8, 9]. So far, data on potential alterations of left and right ventricular function in association with an increase of cardiovascular biomarkers after an ultramarathon are limited [9, 10]. Moreover, it is unclear if changes in cardiac function after an UM are transitory and only present directly after the event, or if theses alterations persist during the days thereafter as well. Thus, the hypothesis of the present study is to investigate if potential acute effects of an UM (130 km) on left and right ventricular function are in relation to an increase of hs-cTnI and NT-proBNP after the competition.

Methods

Study Design

The study design has been described previously [6, 7]. This is a prospective, observational study including non-professional athletes. All participants competed in an UM event with a running distance of 130 km. Athletes were invited for three study visits: a baseline visit within five days before the running event; a post-race visit immediately after race, and a follow-up visit five days after the event. Each study visit included a full medical check-up including physical examination, blood sampling, resting 12-lead electrocardiogram, and echocardiography (Fig. 1). The BORG 6–20 scale was used to assess post-race fatigue [11]. Apart from the study visit immediately after the race, all were conducted at the 3rd Medical Department with Cardiology and Intensive Care Medicine, Clinic Ottakring, Vienna.

Individuals were eligible for study inclusion if they were at least 18 years old and had no previous history of cardiac or pulmonary disease (including myocardial infarction, heart failure, valvular disease, congenital heart disease and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease). Potential candidates were required to have previously participated in a regular marathon or ultramarathon. Participants completed the ultra-marathon (“Rundumadum”, Vienna, https://www.wien-rundumadum.at/), which was held in October 2016 and covered 130 km with elevation gains of 1170 m. The track was of asphalt and trail. The time limit given by the organizers to complete the race were 25 h. Written informed consent was obtained from all study participants before any study procedure was performed. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the local ethics committee (EK-16-057-VK, 11/05/2016). Wegberger et al. [6] and Kaufmann et al. [7] previously reported data of this study cohort with respect to biomarkers of cardiovascular stress, iron homeostasis and inflammation. Norm values for NT-proBNP are 0–125 ng/L. The upper reference limit (99th percentile) of hs-cTnI is 0.045 ng/mL. The present study resembles a post-hoc analysis investigating the cardiac function by echocardiography of all participants and their association with cardiac biomarkers.

Study Population

Study recruitment was performed by an open invitation letter published on the official website and regular newsletters of the organizers of the “Rundumadum” Vienna run. Athletes replied voluntarily to the announcement of our study and were invited to the baseline visit if fulfilling all inclusion criteria, being ≥ 18 years, of good health without significant comorbidities and prior participation in a regular marathon or an UM.

Echocardiographic Exam

A standardized resting echocardiographic exam was performed in left lateral decubitus position at all study visits by experienced operators. Echocardiographic examination was performed using two portable echocardiographs (Vivid iq, General Electrics, WI, USA), equipped with a M4S 1.5–4.0 MHz transducer. Post-exam analyses were performed using a dedicated software (EchoPac, GE, USA). Left atrial volume was assessed using the end-systolic four- and two-chamber views and were indexed to the body surface area (LAVI). Left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) was calculated by the Simpson equation using apical four and two-chamber views. Averaged left ventricular global longitudinal strain (GLS) was measured from apical two-, three- and four-chamber views. For right heart assessment a modified apical four-chamber view was acquired. Right ventricular fractional area change (FAC) was measured using end-diastolic and end-systolic areas. Right ventricular global longitudinal free wall strain (GFWS) was assessed using a four-chamber view. All parameters were assessed over three cardiac cycles and then averaged.

Statistical Analysis

Categorical variables are depicted as counts and percentage. Parametric variables are depicted as mean and standard deviation (SD). The Shapiro–Wilk test was used to check for normality. For comparison of echocardiographic parameters obtained before the UM, immediately and five days after the race, repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) was applied. Fisher’s least significant difference method was used as a post-hoc test for pairwise comparison. The study population was stratified according to the median plasma levels of hs-TnI and NT-proBNP to compare cardiac function in participants with or without substantial biomarker elevation. All statistical analyses were 2-tailed, and a p-value < 0.05 was required for statistical significance. All statistical analyses were performed with SPSS 27.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

A total of 16 athletes provided informed consent and were recruited for this study. One participant had to be excluded from the final analysis due to non-completion, resulting in a final study population of 15 athletes for full analysis. The mean age of the study population was 42.9 ± 8.0 years with one (6.7%) female participant. All athletes were amateur marathon runners, but had previously completed several UM (n = 11.9 ± 7.8). Participants were in healthy clinical condition without prior cardiovascular or pulmonary comorbidities and no history of smoking. Athletes completed the UM in a mean of 956 min (± 131 min) time with an average speed of 8.0 ± 1.3 km/h, respectively. The level of fatigue quantified with the BORG scale was 15.8 ± 1.6 for the UM (Table 1).

Changes in Echocardiographic Parameters after the Ultramarathon

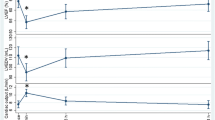

The mean LVEF of the study population before the UM was 57.0 ± 6.7%, with a mean GLS of − 19.0 ± 1.8 and a LAVI of 28.4 ± 7.3 ml/m2. No significant change in left ventricular function or LAVI was observed after the UM (Table 2). Right ventricular function quantified as FAC was significantly reduced directly after the UM (48.0 ± 4.6 vs. 46.7 ± 3.8, p = 0.030), whereas GFWS (− 26.4 ± 2.4 vs. − 24.8 ± 2.7, p = 0.766) was similar before and after the UM. The exercise-induced reduction in FAC persisted five days after the UM (48.0 ± 4.6 vs. 46.3 ± 3.9, p = 0.027), while GFWS remained unchanged (− 26.4 ± 2.4 vs. − 27.0 ± 2.7, p = 0.150).

Echocardiographic Parameters in Relation to Cardiovascular Biomarkers

A significant increase in hs-cTnI and NT-proBNP was observed directly after the UM, which normalised within the following five-day period as previously shown [6]. Participants were stratified according to the median biomarker concentration of hs-cTnI (0.056 ng/ml [IQR: 0.022–0.104] and NT-proBNP (723 ng/L [IQR: 378–1152] assessed immediately after the UM (Table 3 and 4). Participants with plasma levels above the median NT-proBNP had a significantly reduced LVEF (60.8 ± 3.6% vs. 56.9 ± 4.8%, p = 0.030) directly after the UM that persisted until day five (60.8 ± 3.6% vs. 55.3 ± 4.5%, p = 0.007). Right ventricular function in terms of FAC was not significantly altered in the overall comparison of the three measurements (p = 0.184, Table 4), but a significant reduction in FAC was observed five days after the race compared to the baseline value in patients with NT-proBNP above the median (48.4 ± 5.1% vs. 44.3 ± 3.9%, p = 0.044). No significant changes in GLS, GFWS or LAVI were observed in relation to NT-proBNP (Tables 3 and 4).

Participants with plasma levels of hs-cTnI above the median had a significantly reduced FAC directly after the race compared to the baseline visit (48.4 ± 5.1% vs. 46.5 ± 4.3%, p = 0.038), which was not observed in the overall comparison of the three measurements (p = 0.108). No significant difference in left ventricular function, GFWS or LAVI was observed in relation to plasma levels of hs-cTnI (Tables 3 and 4, Fig. 2).

Stratified to the median finish time of 999 min, participants with a finish time below the median had no different levels of NT-proBNP (812 ± 588 vs. 815 ± 523, p = 0.992) or hs-cTnI (0.123 ± 0.125 ng/ml vs. 0.045 ± 0.024, p = 0.128) compared to athletes with a finish time above the median.

Discussion

The main finding of the present study was that only participants of an UM with a biomarker elevation above the median of hs-cTnI and NT-proBNP experienced a decline in cardiac function after the race which was not observed in athletes with biomarker levels below the median. These findings indicate a biomarker-associated impact of prolonged strenuous exercise on cardiac function, which may only be present in participants with a substantial elevation of hs-cTnI or NT-proBNP after the race.

Previous studies indicated that participation in endurance competitions with high cardiac workload over a substantial period may be associated with a transient decline in cardiac function immediately after the race [3,4,5]. A slight decrease in LVEF and a significant impact on right ventricular function with a reduction of FAC and right ventricular strain was reported in participants of ultra-endurance races, although these findings were not confirmed in other studies [4, 5, 12, 13]. More recently, a study by Cavigli et al. reported no significant changes in biventricular function in participants of an UM of 50km [12]. However, data on potential alterations of right or left ventricular function in participants of an ultra-endurance race in association with an elevation of biomarkers of cardiovascular stress are limited [10, 13].

It is well established that prolonged strenuous exercise may lead to an elevation of cardiovascular biomarkers such as hs-cTnI and NT-proBNP [6, 14,15,16]. Zebrowska et al. demonstrated in participants of a 24-h ultramarathon that cTnI and NT-proBNP were significantly elevated directly and one day after the race [17]. Systolic left or right ventricular function was not different comparing pre- to post-race evaluation in this analysis, although a significant change in diastolic function was observed [17]. Christensen et al. reported significantly elevated plasma levels of hs-cTnI in participants of a 63-km ultramarathon which was inversely associated with a significant decrease in post-race LVEF [10]. While a significant increase in hs-cTnI and NT-proBNP was seen in the present study [6], reduced cardiac function was not observed in participants with plasma levels of hs-cTnI or NT-proBNP below the median. On the contrary, a decline in right and left ventricular function was only seen in participants with concentrations of NT-proBNP or hs-cTnI above the median as assessed directly after the UM. This finding may indicate that a significant elevation of hs-cTnI and NT-proBNP directly after the race is associated with exercise-induced impairment of cardiac function. Prolonged strenuous exercise may only impact cardiac function in participants with a substantial elevation of hs-cTnI or NT-proBNP after the race.

Increased levels of hs-cTnI can be observed in various clinical conditions leading to cardiac injury, ranging from type 1 myocardial infarction, to tachyarrhythmias or hypertensive emergencies [18]. Prolonged strenuous exercise may lead to elevated hs-cTnI via a similar pathway of cardiac injury [18]. However, Tahir et al. demonstrated that elevation of cTnI after completion of a triathlon was not associated with detectable myocardial oedema by cardiac magnetic resonance imaging [19], indicating that post-exercise elevation of hs-cTnI may be secondary to benign leakage in contrast to myocyte injury or necrosis [19]. In the present study, patients with NT-proBNP levels above the median had a significant reduction of LVEF and FAC after the UM. Potential mechanisms of the transient alterations in cardiac function are not yet fully clarified [20], but may be related to a relative volume overload of the right and left ventricle during prolonged endurance exercise. Increased plasma levels of NT-proBNP may reflect an activation of the cardiac neuroendocrine system secondary to continuous hemodynamic overload [21]. This may explain why the alteration in LVEF and FAC in the present study was more pronounced in relation to NT-proBNP as compared to hs-cTnI. Additional factors may include an increase of markers of systemic stress and a downregulation of cardiac beta-adrenergic receptors after prolonged endurance exercise which might contribute to a transient decline in LVEF and FAC [22,23,24].

The exercise-induced alteration of LVEF in relation to NT-proBNP in the present study persisted over the early recovery period of five days. Potential long-term effects of these changes in cardiac function are not fully clarified yet, as a few studies reported persistent alterations up to four weeks after prolonged strenuous exercise [25, 26]. Nevertheless, in regards to clinical implications it is important to note that the participants of the present study completed several UM before the conduction of this analysis and retained normal left and right ventricular function. In addition, biomarker elevation normalised within a few days after the event. Thus, a potential impact on long-term cardiac function may be unlikely, although further research is warranted with this respect.

Limitations

Several important limitations of this study need to be acknowledged. The relative small sample size of the present study and the underrepresentation of female athletes limit the generalizability of the findings and warrant confirmation in larger and more comprehensive study populations. This might be relevant as small effect sizes or potential confounding factors could be outside the reliability of the measures or not big enough to be detected with the power of this study. In addition, this analysis utilized a data-driven cut off (median elevation of biomarkers after the UM) in the lack of established reference values for NT-proBNP and hs-cTnI elevation in this particular setting. Adjustment for multiple comparison was not performed considering the exploratory nature of this study. Some echocardiographic parameters were not available in all athletes at all study visits (Table S3). A requirement for study participation was prior participation in a regular marathon or an UM. However, data on prior participation of an UM is missing in five of the 15 participants (supplementary Table S1). Furthermore, the present study investigated acute effects of ultra-endurance exercise, but no long-term follow-up data is available to draw conclusions on potential long-term effects.

Conclusions

Participation in ultra-endurance competitions with prolonged strenuous exercise was associated with a slight decline in right and left ventricular function in athletes with an elevation of hs-cTnI or NT-proBNP above the median. This alteration was not observed in participants with hs-cTnI or NT-proBNP levels below the median. Potentially, substantial elevation of hs-cTnI and NT-proBNP directly after an UM is associated with exercise-induced impairment of cardiac function.

Availability of Data and Materials

The underlying data of this study are available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

- FAC:

-

Fractional area change

- GFWS:

-

Right ventricular global longitudinal free wall strain

- GLS:

-

Global longitudinal strain

- hs-cTnI:

-

High-sensitivity cardiac Troponin I

- km:

-

Kilometres

- LAVI:

-

Left atrial volume index

- LV:

-

Left ventricular

- LVEF:

-

Left ventricular ejection fraction

- NT-proBNP:

-

N-terminal-pro brain natriuretic peptide

- RV:

-

Right ventricular

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- UM:

-

Ultramarathon

References

Shiroma EJ, Lee IM. Physical activity and cardiovascular health: lessons learned from epidemiological studies across age, gender, and race/ethnicity. Circulation. 2010;122(7):743–52.

Moore SC, Patel AV, Matthews CE, Berrington de Gonzalez A, Park Y, Katki HA, Linet MS, Weiderpass E, Visvanathan K, Helzlsouer KJ, Thun M, Gapstur SM, Hartge P, Lee IM. Leisure time physical activity of moderate to vigorous intensity and mortality: a large pooled cohort analysis. PLoS Med. 2012;9(11):e1001335.

Wolff S, Picco JM, Díaz-González L, Valenzuela PL, Gonzalez-Dávila E, Santos-Lozano A, Matile P, Wolff D, Boraita A, Lucia A. Exercise-induced cardiac fatigue in recreational ultramarathon runners at moderate altitude: insights from myocardial deformation analysis. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2021;8:744393.

Lord R, Somauroo J, Stembridge M, Jain N, Hoffman MD, George K, Jones H, Shave R, Haddad F, Ashley E, Oxborough D. The right ventricle following ultra-endurance exercise: insights from novel echocardiography and 12-lead electrocardiography. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2015;115(1):71–80.

Oxborough D, Shave R, Warburton D, Williams K, Oxborough A, Charlesworth S, Foulds H, Hoffman MD, Birch K, George K. Dilatation and dysfunction of the right ventricle immediately after ultraendurance exercise: exploratory insights from conventional two-dimensional and speckle tracking echocardiography. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2011;4(3):253–63.

Wegberger C, Tscharre M, Haller PM, Piackova E, Vujasin I, Gomiscek A, Tentzeris I, Freynhofer MK, Jäger B, Wojta J, Huber K. Impact of ultra-marathon and marathon on biomarkers of myocyte necrosis and cardiac congestion: a prospective observational study. Clin Res Cardiol: Off J German Card Soc. 2020;109(11):1366–73.

Kaufmann CC, Wegberger C, Tscharre M, Haller PM, Piackova E, Vujasin I, Kassem M, Tentzeris I, Freynhofer MK, Jäger B, Wojta J, Huber K. Effect of marathon and ultra-marathon on inflammation and iron homeostasis. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2021;31(3):542–52.

Urhausen A, Scharhag J, Herrmann M, Kindermann W. Clinical significance of increased cardiac troponins T and I in participants of ultra-endurance events. Am J Cardiol. 2004;94(5):696–8.

Scott JM, Esch BT, Shave R, Warburton DE, Gaze D, George K. Cardiovascular consequences of completing a 160-km ultramarathon. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2009;41(1):26–34.

Christensen DL, Espino D, Infante-Ramírez R, Cervantes-Borunda MS, Hernández-Torres RP, Rivera-Cisneros AE, Castillo D, Westgate K, Terzic D, Brage S, Hassager C, Goetze JP, Kjaergaard J. Transient cardiac dysfunction but elevated cardiac and kidney biomarkers 24 h following an ultra-distance running event in Mexican Tarahumara. Extreme Physiol Med. 2017;6(1):3.

Borg GA. Psychophysical bases of perceived exertion. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1982;14:377–81.

Cavigli L, Zorzi A, Spadotto V, Gismondi A, Sisti N, Valentini F, Anselmi F, Mandoli GE, Spera L, Di Florio A, Baccani B, Cameli M, D’Ascenzi F. The acute effects of an ultramarathon on biventricular function and ventricular arrhythmias in master athletes. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2022;23(3):423–30.

Tulloh L, Robinson D, Patel A, Ware A, Prendergast C, Sullivan D, Pressley L. Raised troponin T and echocardiographic abnormalities after prolonged strenuous exercise—The Australian Ironman Triathlon. Br J Sports Med. 2006;40(7):605–9.

Perrone MA, Macrini M, Maregnani A, Ammirabile M, Clerico A, Bernardini S, Romeo F. The effects of a 50 km ultramarathon race on high sensitivity cardiac troponin I and NT-proBNP in highly trained athletes. Minerva Cardioangiol. 2020;68(4):305–12.

Ohba H, Takada H, Musha H, Nagashima J, Mori N, Awaya T, Omiya K, Murayama M. Effects of prolonged strenuous exercise on plasma levels of atrial natriuretic peptide and brain natriuretic peptide in healthy men. Am Heart J. 2001;141(5):751–8.

Cantinotti M, Clerico A, Giordano R, Assanta N, Franchi E, Koestenberger M, Marchese P, Storti S, D’Ascenzi F. Cardiac troponin-T release after sport and differences by age, sex, training type, volume, and intensity: a critical review. Clin J Sport Med. 2022;32(3):e230–42.

Żebrowska A, Waśkiewicz Z, Nikolaidis PT, Mikołajczyk R, Kawecki D, Rosemann T, Knechtle B. Acute responses of novel cardiac biomarkers to a 24-h ultra-marathon. J Clin Med. 2019;8(1).

Collet JP, Thiele H, Barbato E, Barthélémy O, Bauersachs J, Bhatt DL, Dendale P, Dorobantu M, Edvardsen T, Folliguet T, Gale CP, Gilard M, Jobs A, Jüni P, Lambrinou E, Lewis BS, Mehilli J, Meliga E, Merkely B, Mueller C, Roffi M, Rutten FH, Sibbing D, Siontis GCM. 2020 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation. Eur Heart J. 2021;42(14):1289–367.

Tahir E, Scherz B, Starekova J, Muellerleile K, Fischer R, Schoennagel B, Warncke M, Stehning C, Cavus E, Bohnen S, Radunski UK, Blankenberg S, Simon P, Pressler A, Adam G, Patten M, Lund GK. Acute impact of an endurance race on cardiac function and biomarkers of myocardial injury in triathletes with and without myocardial fibrosis. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2020;27(1):94–104.

Knechtle B, Nikolaidis PT. Physiology and pathophysiology in ultra-marathon running. Front Physiol. 2018;9:634.

Scharhag J, Herrmann M, Urhausen A, Haschke M, Herrmann W, Kindermann W. Independent elevations of N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide and cardiac troponins in endurance athletes after prolonged strenuous exercise. Am Heart J. 2005;150(6):1128–34.

Hart E, Dawson E, Rasmussen P, George K, Secher NH, Whyte G, Shave R. Beta-adrenergic receptor desensitization in man: insight into post-exercise attenuation of cardiac function. J Physiol. 2006;577(Pt 2):717–25.

Scott JM, Esch BT, Haykowsky MJ, Isserow S, Koehle MS, Hughes BG, Zbogar D, Bredin SS, McKenzie DC, Warburton DE. Sex differences in left ventricular function and beta-receptor responsiveness following prolonged strenuous exercise. J Appl Physiol. 2007;102(2):681–7.

Bizjak DA, Schulz SVW, John L, Schellenberg J, Bizjak R, Witzel J, Valder S, Kostov T, Schalla J, Steinacker JM, Diel P, Grau M. Running for Your Life: Metabolic Effects of a 160.9/230 km Non-Stop Ultramarathon Race on Body Composition, Inflammation, Heart Function, and Nutritional Parameters. Metabolites. 2022;12(11).

Neilan TG, Yoerger DM, Douglas PS, Marshall JE, Halpern EF, Lawlor D, Picard MH, Wood MJ. Persistent and reversible cardiac dysfunction among amateur marathon runners. Eur Heart J. 2006;27(9):1079–84.

La Gerche A, Connelly KA, Mooney DJ, MacIsaac AI, Prior DL. Biochemical and functional abnormalities of left and right ventricular function after ultra-endurance exercise. Heart. 2008;94(7):860–6.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This research was supported by Association for the Promotion of Research on Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology (ATVB); Ludwig Boltzmann Cluster for Cardiovascular Research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All study authors contributed to the conduction and analysis of this study’s data, to the writing of this manuscript and approved the submission, as shown in detail below. The authors take full responsibility for this work. ALB: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data Curation, Writing—Original Draft, Visualization. CW: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data Curation, Writing—Review & Editing. MT: Conceptualization, Methodology, Data Curation, Writing—Review & Editing, Supervision, Project administration. CCK: Conceptualization, Methodology, Data Curation, Writing—Review & Editing. MM: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing—Review & Editing. EP: Conceptualization, Methodology, Data Curation, Writing—Review & Editing, Supervision, Project administration. MKF: Conceptualization, Methodology, Data Curation, Writing—Review & Editing, Supervision, Project administration. AS Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing—Review & Editing. KH Conceptualization, Methodology, Resources, Writing—Review & Editing, Supervision, Funding Acquisition, project administration. BJ Conceptualization, Methodology, Resources, Data curation, formal analysis, Writing—Review & Editing, Supervision, project administration.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

Written informed consent was obtained from all study participants before any study procedure was performed. The study was conducted in accordance with the standards of ethics outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. The study was approved by the local ethics committee of the city of Vienna (EK-16-057-VK).

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors report no conflict of interest, neither in financial, professional or personal interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Burger, A.L., Wegberger, C., Tscharre, M. et al. Impact of an Ultra-Endurance Marathon on Cardiac Function in Association with Cardiovascular Biomarkers. Sports Med - Open 10, 67 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40798-024-00737-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40798-024-00737-1