Abstract

Background

Musculoskeletal conditions are a leading contributor to disability worldwide. The treatment of these conditions accounts for 7% of health care costs in Germany and is often provided by physiotherapists. Yet, an overview of the cost-effectiveness of treatments for musculoskeletal conditions offered by physiotherapists is missing. This review aims to provide an overview of full economic evaluations of interventions for musculoskeletal conditions offered by physiotherapists.

Methods

We systematically searched for publications in Medline, EconLit, and NHS-EED. Title and abstracts, followed by full texts were screened independently by two authors. We included trial-based full economic evaluations of physiotherapeutic interventions for patients with musculoskeletal conditions and allowed any control group. We extracted participants' information, the setting, the intervention, and details on the economic analyses. We evaluated the quality of the included articles with the Consensus on Health Economic Criteria checklist.

Results

We identified 5141 eligible publications and included 83 articles. The articles were based on 78 clinical trials. They addressed conditions of the spine (n = 39), the upper limb (n = 8), the lower limb (n = 30), and some other conditions (n = 6). The most investigated conditions were low back pain (n = 25) and knee and hip osteoarthritis (n = 16). The articles involved 69 comparisons between physiotherapeutic interventions (in which we defined primary interventions) and 81 comparisons in which only one intervention was offered by a physiotherapist. Physiotherapeutic interventions compared to those provided by other health professionals were cheaper and more effective in 43% (18/42) of the comparisons. Ten percent (4/42) of the interventions were dominated. The overall quality of the articles was high. However, the description of delivered interventions varied widely and often lacked details. This limited fair treatment comparisons.

Conclusions

High-quality evidence was found for physiotherapeutic interventions to be cost-effective, but the result depends on the patient group, intervention, and control arm. Treatments of knee and back conditions were primarily investigated, highlighting a need for physiotherapeutic cost-effectiveness analyses of less often investigated joints and conditions. The documentation of provided interventions needs improvement to enable clinicians and stakeholders to fairly compare interventions and ultimately adopt cost-effective treatments.

Key Points

-

Several high-quality economic evaluations of physiotherapeutic treatments for the back and knee exist

-

Economic evaluations of other joints are rare

-

Physiotherapeutic interventions are often cost-effective over treatments provided by other health professionals

-

The description of provided interventions in cost-effectiveness analyses needs improvement, to allow fair treatment comparisons

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Rationale

Globally about 1.71 billion people suffer from a musculoskeletal condition [1]. Most adults in rehabilitation within Germany present with this diagnosis [2]. These patients have an increased risk of developing additional chronic diseases and mental health problems, which further increase the patients’ burden [3, 4]. Rehabilitation programs, aiming at reducing these patients' burden and their duration of sick leave, are often planned, and implemented by physiotherapists. Their and other therapeutic services account for 7% of the health expenditures in Germany (2021) and thus cause a financial burden for society [5].

Physiotherapeutic treatments have been used before clinical studies were conducted, but in the last decades, several interventions for specific diseases have been evaluated regarding their clinical effectiveness—although some intervention-disease-combinations remain yet unexplored. In recent years, besides their clinical effectiveness, the costs involved with a treatment have become additionally important to the stakeholders. The combined information supports their decision on whether a treatment should be implemented or de-implemented [6]. Full economic evaluations furnish this information on the anticipated costs along with the expected clinical outcomes of an intervention, enabling comparisons between various disease interventions and by this providing insight into possible cost savings. The costs presented in such analyses consider either healthcare costs alone or both healthcare costs and societal costs [6].

Several studies have already demonstrated that physiotherapists offer treatments worth the money [7, 8]. One review provides an overview of economic evaluations for treatments of neurological conditions offered by physiotherapists [9] and another review evaluates the cost-effectiveness of physical exercise, which is one of the treatment modalities offered by physiotherapists, for various health conditions [10]. However, an overview of existing economic evaluations of different physiotherapeutic treatment modalities for patients with musculoskeletal conditions is missing. Such an overview allows physiotherapists to easily identify relevant publications. Furthermore, it enables policymakers to easily identify relevant studies and researchers to plan future investigations.

Objectives

In this review, we therefore aim to:

-

provide an overview of existing full economic evaluations of interventions for patients with musculoskeletal conditions offered by physiotherapists.

-

shed light on the cost-effectiveness of physiotherapeutic interventions for specific musculoskeletal health conditions.

-

highlight for which health conditions further research is needed.

Methods

Protocol and Registration

A protocol for this review was published and additionally registered at Prospero (CRD42021276050) [11]. We followed our protocol but decided to report the findings of the identified trial and model-based economic evaluations separately. This allows us to fully account for and address the heterogeneous aspects of the two study types. Here we present our findings from the trial-based publications. We report our results following the PRISMA statement.

Eligibility Criteria

We included full economic evaluations of physiotherapeutic interventions for patients with musculoskeletal conditions. To specify our inclusion and exclusion criteria, we used the PICOS acronym (population, intervention, control group, outcome, study type).

Our population of interest suffered from a musculoskeletal condition. If the majority had another primary disease or if the participants had intellectual disabilities, we excluded the publication.

We included publications where physiotherapists provided one of the intervention/control group treatments alone. We excluded publications if the treatment of interest was offered by an interdisciplinary team, non-healthcare professionals, or mostly by a different profession. If the physiotherapeutic treatment of interest was combined with another treatment, this needed to be provided in a comparator group as well. Thus, an isolated incremental effect evaluation of a physiotherapeutic intervention needed to be possible. Economic evaluations of E-intervention were excluded.

We allowed any type of control group including wait-and-see, usual care, placebo, and alternative treatments, and excluded publications where no control group was considered.

Our outcome needed to be the result of a full health economic evaluation, including cost-effectiveness ratios, and cost-utility ratios.

Economic evaluations based on models and clinical trials were included during the screening process. We excluded Delete 'study types like' conference abstracts, reviews, books, and articles with no access and studies without results, e.g. protocols. In this publication, we additionally excluded model-based studies during the full-text screening, to reduce heterogeneity of included studies and allow a fair comparison of the study quality.

Finally, the economic evaluation needed to be published in Danish, English, or German.

Information Sources

We searched for relevant publications in the databases Medline (through PubMed), EconLit, and NHS-EED (can only be searched up to March 2015). The initial search was performed at the end of January 2022 and the final update was performed on the 8th of December 2023.

Search Strategy

We used the three main search terms ‘economic evaluation’, ‘physiotherapy’, and ‘orthopedic’ to develop a search matrix. For each of the main search terms we collected synonyms and combined them with an ‘OR’ in a search. Afterwards, we merged the three synonym searches with two ‘AND’. Utilizing asterisks reduced the number of search terms but allowed identifying relevant articles. Our search string in PubMed consequently was: ((((economic analy*) OR (cost analy*) OR (cost benefit*) OR (cost utility) OR (cost effectiveness) OR (economic evaluation))) AND (((orthopaedic rehabilitation) OR (physical rehabilitation) OR (exercise therap*) OR (conservative therap*) OR (conservative management) OR (conservative treatment) OR (exercise training) OR (physiotherap*))) AND (((muskuloskeletal) OR (chirur*) OR (orthop*) OR (osteoarthritis) OR (back pain)))). "Details on the PubMed search" are also available in Additional file 1: Table S1.

Selection Process

After removing duplicates, we applied a two-step study selection process. In the first step, we screened the title and abstracts for our inclusion and exclusion criteria. In the second step, we evaluated the full texts. Both steps were conducted by two independent reviewers at any time (LB, WF, BK). After each step, the involved authors compared their results and resolved disagreements via discussions or consulting a third reviewer (HHK) if needed.

Data Collection Process

The spreadsheet for data extraction was independently tested on three included publications by two authors (LB, BK). The authors discussed uncertainties, adjusted the labeling in the spreadsheet, and repeated the process. The authors agreed in the second round and LB proceeded with the data extraction. WF became involved in the data extraction process after she compared the data extraction results of three publications with LB, and no disagreement occurred.

Data Items

In total, we extracted the following items per publication: authors, year of publication, sample size, mean age, the proportion of female sex, health condition, location, type of economic analysis, cost perspective, economic effect measure, time horizon, study design, setting, and frequency, intensity, duration as well as the type of intervention, further control intervention, cost-effectiveness results, and finally the author’s conclusion. If the modalities of an intervention were not presented in a publication, but a reference was mentioned, we extracted the information from the cited publication. Further, in articles with several physiotherapeutic intervention or control groups, we ordered the interventions of interest as primary, secondary and so on. We prioritized basic interventions as primary, meaning interventions which could be most easily provided by physiotherapists—without further training.

Critical Appraisal of the Included Publications

We utilized the Consensus on Health Economic Criteria checklist for evaluating the quality of the included articles [12]. This tool consists of 19 questions which can be answered with ‘yes’ or ‘no’ each. Each ‘yes’ indicates good quality, whereas a ‘no’ indicates limited quality.

Two authors (LB and HHK) independently assessed the quality of three articles. After discussing uncertainties LB proceeded with the evaluation. WF got involved in the assessment after she and LB agreed on the quality of three, independently evaluated, articles.

Synthesis of Results

We provide a descriptive overview of the available literature. We categorized the economic evaluations based on the affected body parts. Afterwards, we grouped all cost-effectiveness comparisons, which are partly between two physiotherapeutic interventions, and partly between a physiotherapeutic and another intervention, of the included articles according to the four quadrants of a cost-effectiveness plane (I. more costly, more effective; II. more costly, less effective (dominated); III. less costly, less effective; IV. less costly, more effective (dominant)). The IV. quadrant is always assumed to be cost-effective, and the II. quadrant is always dominated, hence not cost-effective in the performed comparison. However, whether the interventions are cost-effective in the other two quadrants (I. and III.), depends on the stakeholder’s willingness to pay for an extra benefit in a health outcome. As an example, if a health system is not willing to pay the additional costs for the gain in health outcomes in the comparison group, our (primary) interventions in the III. quadrant would be cost-effective. However, if the healthcare system is willing to pay the additional costs to achieve the additional benefit in the health outcome, our (primary) interventions grouped in the I. quadrant would be cost-effective. Thus, to determine if interventions of the I. and III. quadrants are cost-effective, we would need to know the amount of money the healthcare system or society is willing to pay for a one-unit gain in the respected health outcome. However, this is beyond the scope of this review. For comparisons between two physiotherapeutic interventions, we defined one intervention as the primary intervention of interest. These primary physiotherapeutic interventions were more likely offered solely by physiotherapists and required least additional training/courses for the physiotherapists.

Results

Selection of Publications

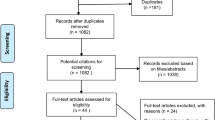

Our search findings and the study selection process are visualized in the flowchart Fig. 1. In total, we identified 5141 eligible publications of which 83 met our inclusion criteria. A list of the publications excluded during the full-text screening process including an indication of the reason for exclusion is provided in Additional file 2: Table S2.

Characteristics of the Economic Evaluations

Table 1 summarizes our included 83 articles which were based on 78 clinical trials [13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95]. Niemistö et al., Barker et al., Skargren et al. as well as Hurley et al. published two articles each building on one trial [17, 18, 51, 52, 72, 81, 82, 96]. Abbott et al. and Pinto et al. utilized data from the MOA RCT [13, 74]. All articles were published between 1994 and 2023 (Fig. 2). The majority of the 78 clinical trials were RCTs (n = 71) and 71 of the articles originated from the Western world. The UK (n = 23) and the Netherlands (n = 22) contributed more than 50% of the articles (Fig. 3). The time horizon of the economic evaluations varied between 5 days and 36 months. In Table 1 the included articles are grouped by their addressed body parts: spine (n = 39), upper limb (n = 8), lower limb (n = 30), and other conditions (n = 6). The most frequently investigated conditions were low back pain (n = 25) and hip and knee osteoarthritis (n = 16). In most included samples the mean age was between 45 and 65 and the distribution of female and male participants was between 40 to 60%. If a sample deviated from this, the mean age and female percentage were added in Table 1.

The outcomes of the included studies needed to involve a clinical outcome as well as the economic outcome costs. The latter was evaluated from a health-payer perspective in 50 cases and in 36 cases from a societal perspective (Table 1). As the numbers indicate, some studies presented costs for both perspectives. The most frequently utilized clinical outcomes were quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs), which were assessed via the EQ-5D (n = 39) and the SF6 or SF12 (n = 9). Disease-specific disability scores were assessed second most often (n = 9), e.g. via the Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire. Finally, pain intensity was used in five publications. The remaining publications used individual outcome measures such as bothersomeness of symptoms, a stair climbing task, and blood pressure (Table 1).

In Table 2, we present details on the interventions and highlight our defined primary intervention. The articles involved 150 comparisons between physiotherapeutic interventions and comparators. Figures 4 and 5 display the results in terms of differences in costs and effects grouped qualitatively according to the four quadrants of the cost-effectiveness plane. Eighty-one comparisons involved one treatment provided by a physiotherapist versus another non-physiotherapeutic intervention (Fig. 4), while 69 of the comparisons were between two physiotherapeutic treatments (Fig. 5).

Cost-effectiveness plane of any physiotherapeutic intervention versus another non-physiotherapeutic intervention. BH, behavior; ED, education; EX, exercises; H, home; IN, injection; MD, medical doctor; MT, manual therapy; MX, mixed; OT, others; PT, physiotherapy; SU, surgery; b, booster session; eb, evidence-based; g, group; i, individual; p, placebo; s, stratified care; u, usual; w, written; 2×, twice, *physiotherapeutic intervention, #no significant differences in the health outcome, ‘no significant differences in the costs

Cost-effectiveness plane of a primary physiotherapeutic intervention vs another physiotherapeutic intervention. BH, behavior; ED, education; EX, exercises; H, home; IN, injection; MD, medical doctor; MT, manual therapy; MX, mixed; OT, others; PT, physiotherapy; SU, surgery; b, booster session; eb, evidence-based; g, group; i, individual; p, placebo; s, stratified care; u, usual; w, written; 2×, twice; *physiotherapeutic intervention, #no significant differences in the health outcome, ‘no significant differences in the costs

Critical Appraisal of the Included Articles

More than two-thirds of the included 83 trials-based economic evaluations were of high quality with sum-yes-scores of 17 (n = 13), 18 (n = 16), or 19 (n = 31) on the Consensus on Health Economic Criteria checklist (Additional file 3: Table S3). The lowest score was 11 which was observed in two articles. Scores of 12, 13, and 14 were observed in two articles each. The scores 15, and 16 were reached by five and ten articles, respectively. The three items “Is a well-defined research question posed in answerable form?”, “Is the actual perspective chosen appropriate?”, and “Are all outcomes measured appropriately?” were evaluated with a ‘Yes’ for all the articles. The lowest sum of positive evaluation was observed for the item “Does the article indicate that there was no potential conflict of interest of study researchers and funders?” (n = 58). Limitations were also observed in 23 articles when it comes to the performance of incremental analyses of the costs and outcomes of alternatives. Fifty-nine publications met the criteria regarding sensitivity analyses to account for uncertain variable values. Nonetheless, the overall article quality was high.

Results of Syntheses Grouped by Body Parts

Spine

Of our 39 articles dealing with spine-related conditions four address the back in general [17, 18, 71, 84], 25 deal with the low back [14,15,16, 21, 26,27,28,29, 32, 38, 39, 43, 45, 46, 50, 55, 57, 59, 72, 73, 77, 83, 87, 93, 95], six with the neck [24, 62,63,64, 68, 94] and four include mixed patients [34, 67, 81, 82] (Tables 1, 2).

The four articles on general back conditions [17, 18, 71, 84] built on three clinical trials. The sessions varied between 1 and 36 over a time horizon of 1 to 24 weeks. Most interventions were conducted 1–2 times per week. The duration if indicated varied between 60 and 90 min. The intervention and control groups contained individual and group-based exercise therapy, manual therapy, and education as well as usual care (Table 2). Group exercise therapy was deemed cost-effective over usual care [71] and interpatient exchange group meetings were cost-effective over increasing the frequency of traditional therapy according to the authors [84]. The articles from Barker et al. considered three interventions provided by physiotherapists [17, 18]. The findings of all cost-effectiveness comparisons can be found in Figs. 4 and 5.

The 25 articles on low back pain were built on 24 clinical trials [14,15,16, 21, 26,27,28,29, 32, 38, 39, 43, 45, 46, 50, 55, 57, 59, 72, 73, 77, 83, 87, 93, 95]. Niemistö et al. published two articles based on the same clinical trial [72, 73]. Patients received between 1 and 46 sessions lasting between 20 and 120 min, spread out over a maximum of 30 weeks. Sessions were most often offered 1 to 3 times a week. The treatments in the intervention and control groups included mostly group and individual exercise therapy, individual physiotherapeutic treatments, and education. Additional manual therapy, McKenzie-based treatments, behavioral graded activity, behavior change techniques, a walking program, visits at the workplace, yoga, usual care, chiropractic treatment, and a massage chair were provided (Table 2). Fritz et al. compared individual physical therapy following evidence-based guidelines to physical therapy not following those guidelines and found that following evidence-based guidelines is cost-effective [38]. The articles on low back pain included a total of 67 comparisons of interventions of which 34 were between a physiotherapeutic intervention and another treatment (Figs. 4, 5).

Of the 6 articles on neck conditions all addressed neck pain [24, 62,63,64, 68, 94]. One to 24 sessions were offered. They lasted between 20 and 60 min and were spread over up to 12 weeks. Most treatments were offered 1–2 times per week. The intervention contained exercises, cognitive behavioral treatment, behavior-graded activity, manual therapy, individual therapy, and advice. The control group received exercises, usual care involving physiotherapeutic treatments, and written information (Table 2). The articles involve 12 treatment comparisons. Five highlighted better outcomes at higher costs for the physiotherapeutic intervention, and three were dominant. In the four dominated investigations three of the comparison interventions were offered by physiotherapists (Figs. 4, 5).

Two of the four articles with a mixed spine population originated from the same study. These studies did not differentiate between neck and back pain [34, 67, 81, 82]. Participants received up to 8 sessions. One article focused on physiotherapeutic care in comparison to traditional medical referral care, another compared the McKenzie treatment concept to the individual solution-finding approach, and the remaining two, from the same study, compared physiotherapeutic to chiropractic care (Table 2). Considering only the effectiveness, all articles favored the intervention offered by physiotherapists, although not significantly in the articles by Skargren et al. [81,82]. In the article of Manca et al. the psychotherapeutic treatments involved higher costs [67]; dominance of the physiotherapeutic treatment was found in the remaining articles [34, 81, 82] (Figs. 4, 5).

Upper Limb

The seven papers addressing the upper limb dealt with carpal tunnel syndrome [37], epicondylitis lateralis [61, 86], and shoulder complaints [23, 41, 53] involving a rotator cuff disorder [48]. The number of intervention and control group sessions varied between 3 and 18. Patients were treated 1–2 times a week for 20 to 60 min. All but three articles involved one intervention and one control group. The exceptions involved three different intervention groups. The provided interventions contained manual therapy, education, exercises, and physiotherapeutic treatments such as friction, ultrasound, and massage. The control groups received surgery, injections, braces, and usual care. One study also included a wait-and-see approach (Table 2). The articles involve 14 treatment comparisons. The physiotherapeutic treatment for carpal tunnel syndrome was dominant [37]. The remaining comparison of physiotherapeutic interventions, but one, may as well be cost-effective, depending on the willingness to pay (Figs. 4, 5).

Lower Limb

The included 30 articles built on 28 clinical trials dealing with the lower limb. Of these trials, four addressed the hip [40, 42, 56, 88], nineteen the knee [20, 22, 35, 47, 49, 51, 52, 54, 58, 60, 69, 70, 75, 78, 80, 85, 88, 92], and five a mixed population [13, 25, 31, 36, 66, 74]. Nineteen of the clinical trials dealt with osteoarthritis including the last therapy option of a joint replacement [13, 22, 25, 31, 36, 40, 47, 49, 56, 58, 60, 69, 70, 75, 76, 78, 80, 85, 88].

Among the hip-related clinical trials, three dealt with osteoarthritis and one addressed the femoroacetabular impingement syndrome [42]. Patients participated in 1 to 12 sessions. The duration of a session ranged from 30 to 60 min. The frequency varied between twice a day in the inpatient setting and one time in 2 weeks. The treatments offered contained individual as well as group exercises and education. The control groups received the usual care or an arthroscopy. Besides that, Fusco et al. compared the cost-effectiveness of a treatment with or without limiting hip motion [40] (Table 2). They conclude that not limiting hip motions after a hip replacement is dominant. Similarly, Griffin et al. and Juhakoski et al. highlight dominance of the physiotherapeutic treatment [42, 56]. However, Tan et al. found, that the physiotherapeutic intervention involved cost savings but was also less effective [89] (Figs. 4, 5).

The 19 knee complaint clinical trials bear 20 included articles. Two articles built on one clinical trial dealing with chronic knee pain [64, 65]. One article deals with patellofemoral pain [89], one with ACL tears [35], two with meniscal tears [90, 92], and two with knee pain [20, 54]. The remaining twelve articles investigated treatments for knee osteoarthritis. Patients participated in 1 to 18 sessions spread out mostly over 12 weeks (minimum 6 weeks, maximum 12 months). Inpatients were treated up to twice a day and all patients were treated at least once a month. The intervention for knee pain patients lasted the longest—24 months. Interventions contained mainly individual as well as group-based exercise therapy and education, but manual therapy was also offered in some clinical trials. The control groups received usual care, injections, surgery, education, and physiotherapeutic treatments (Table 2). In total the articles include 40 treatment comparisons (Figs. 4, 5).

Of the five trials on mixed lower limb conditions, we included five articles dealing with hip and knee osteoarthritis [13, 25, 31, 36, 74], and one article on ankle fractures [66]. The patients participated in 6 to 18 sessions spread out over 3 to 12 weeks. Inpatients again received treatments up to twice a day, but most interventions were offered 1–2 times a week. The sessions lasted between 50 and 75 min and contained individual physiotherapeutic treatments, manual therapy, and individual and group-based exercises. The control groups received information, usual care, and individual physiotherapeutic treatments (Table 2). Three articles favored a physiotherapeutic treatment. The remaining articles compared different physiotherapeutic treatments with each other. It was highlighted by the authors, that exercise therapy (individual and group) and education were more cost-effective than usual physiotherapeutic care [25], and that individual physiotherapy alone is cost-effective compared to individual physiotherapy combined with manual therapy [66] (Figs. 4, 5).

Other Conditions

Other conditions evaluated in cost-effectiveness studies included the complex regional pain syndrome [19], musculoskeletal problems [33], rheumatoid arthritis [91], and mixed patients [44, 65, 79] consisting of older adults, sedentary adults, and orthopedic outpatients. Patients participated in 5 to 60 sessions over a maximum of 24 months. The interventions contained individual pain exposure therapy, physiotherapeutic care, education, manual therapy, and group exercises. The control groups received usual care and exercises (Table 2). In each of the six articles only one cost-effectiveness comparison was performed (Figs. 4, 5).

Summary

The provided details on the delivered treatments varied widely between articles. A type of treatment was mentioned in all, however three articles only named “physiotherapy” as treatment without further explanations. Information on the frequency of the treatment was given in 67 articles; 16 provided no information. Similarly, the intensity was mentioned in 53 articles and missing in 30 articles. However, 28 of the 53 articles providing information on the intensity only mention that it was increased during the intervention or tailored to the patient without further explanation. Finally, the dose was mentioned in 55 and lacking in 28 articles (Table 2).

Due to the limited description of the interventions and the heterogeneity of treatment combinations in the intervention and control groups, summarizing comparisons based on interventions was largely restricted.

Nonetheless, in the 81 comparisons between a physiotherapeutic intervention and any other intervention we found the following insights [13, 14, 19, 20, 23, 26, 29, 30, 33,34,35, 37, 39, 41, 42, 45,46,47,48,49, 51,52,53, 55,56,57, 59, 61,62,63, 65, 67, 68, 72, 74, 76, 79,80,81,82, 84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92, 95,96,97]: 27 comparisons were performed between a physiotherapeutic intervention (without care provided by a medical doctor) and an intervention involving care from a medical doctor (Fig. 4) [13, 23, 26, 33, 34, 41, 46, 47, 49, 51, 52, 56, 62, 65, 72,73,74, 88, 91]. Of those about 50% (n = 13) were dominant [13, 34, 46, 47, 49, 51, 56, 62, 72, 74], two were dominated [52, 91], one involved lower costs and lower effects [88], and 11 had better outcomes but involved higher costs [13, 23, 26, 33, 41, 52, 74, 96]. Seven comparisons involved surgery in the control group [35, 37, 42, 85, 92], most of these (n = 6) were more expensive than the physiotherapeutic intervention [35, 37, 42, 85, 92]. The clinical outcome of the physiotherapeutic interventions was better in three of the comparisons [37, 42, 92]. Additionally, we found three comparisons between an intervention provided by a physiotherapist with one provided by a chiropractor [29, 81, 82]. Two originate from the same study and found physiotherapeutic care to be dominant, however, in the third comparison physiotherapeutic care was dominated. Injections were compared to solely other treatments in five comparisons stemming from three studies [30, 48, 53]. In three of these comparisons, physiotherapeutic care was more expensive but led also to better effects [30, 53]. In the remaining two comparisons (from the same study) physiotherapeutic care was cheaper but also less effective (Fig. 4).

Among the 69 comparisons between two physiotherapeutic interventions [13,14,15,16,17,18, 21, 22, 24,25,26,27,28, 31, 32, 38, 40, 43, 44, 48, 50, 52, 54, 57, 58, 60, 62,63,64, 66, 69,70,71, 74, 75, 77, 78, 80, 83, 86, 93, 94], we found 57 mentioning exercises as a treatment modality [13,14,15,16,17,18, 21, 22, 25,26,27,28, 31, 32, 48, 54, 57, 58, 60, 63, 64, 69,70,71, 74, 75, 78, 80, 83, 94, 93], however, it should be noted that if usual physiotherapy was provided this could also include exercises. Nonetheless, since it was not explicitly mentioned we do not consider “usual physiotherapy” as any intervention involving exercises. Of those comparisons 22 mentioned exercises for both comparators. Twenty-four of the comparisons involved manual therapy as part of an intervention, four in both groups [13, 16,17,18, 24, 26, 62,63,64, 66, 74, 75, 94]. Again, it should be noted that individual physiotherapy could have included manual therapies as well but this was not mentioned. Overall, there was no clear trend regarding the cost and the clinical outcomes observed. Having a closer look at comparisons between group-based and individual physiotherapeutic interventions, we found no clear trend regarding cost-effectiveness. This can partly be explained by the mixed treatments that were involved in these interventions as well, hindering clear comparisons.

Discussion

Key Results

Several good quality cost-effectiveness evaluations of physiotherapeutic interventions for patients with musculoskeletal conditions exist. Low back and knee conditions are frequently evaluated, however, for conditions addressing other joints none to few studies are available, here further research is needed. Unfortunately, the description of investigated interventions is often limited in detail and the combination of treatments varies widely. This restricted the ability to fairly compare different treatments.

In the comparisons between a physiotherapeutic intervention and those provided by other health professionals, a minor indication of physiotherapy was found to be cost-effective. Of the 42 comparisons between physiotherapeutic care and care provided by a chiropractor or a medical doctor involving surgeries and injections, we found that 18 were dominant and only four were dominated. For the 14 comparisons with higher costs and better effects, as well as for the 6 with a lower effect and lower costs the willingness to pay is crucial for deciding if the treatment should be considered cost-effective or not. The identification of which physiotherapeutic interventions are cost-effective was hindered by clear descriptions of the provided interventions and similar comparisons of treatment combinations.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first review summarizing the findings of cost-effectiveness evaluations of physiotherapeutic interventions for musculoskeletal conditions. The earliest full-economic evaluation of a physiotherapeutic intervention for a musculoskeletal condition was published in 1994. However, since 2003 at least one new trial-based economic evaluation article has been released each year. This long inclusion period should be noticed when evaluating the relevance of a specific recommended treatment. The physiotherapeutic care and also the comparison treatments could have been enhanced during this time, meaning careful consideration of the (albeit often limited) intervention details is necessary before implementation.

Similarly, when utilizing and comparing the individual study findings of this review the underlying context of the study, the clinical outcome measures, and the findings of the Health Economic Criteria checklist should be considered. Different healthcare systems, as well as the culture of clinicians and patients could influence the cost-effectiveness. As an example, while in some countries like the Netherlands, Great Britain, and Sweden the patients may proceed directly to the physiotherapist, in other countries like Germany they have to consult a medical doctor first—this of course affects the overall cost-effectiveness and should be considered when studies from different countries are compared. Similarly, summarizing and comparing studies that utilized different health outcome measures is challenging. Of course, it is most important that the clinical outcomes are relevant to the patient, however, if different health outcome measures are utilized the comparison of the studies is limited, as the cost-effectiveness might change with a different health outcome. Finally, attention should be given to the evaluation of the Health Economic Criteria checklist of the individual studies/comparisons, which we do not indicate in the cost-effectiveness plane.

The availability of economic evaluation studies in our work mirrors the prevalence of the conditions, which is in line with previous reviews [9, 98]. We found that osteoarthritis was frequently studied. Similarly, a review of orthopedic surgery interventions found that joint arthroplasty, which is the last treatment option for patients with hip and knee osteoarthritis, was commonly investigated in related cost-effectiveness analyses [98]. Additionally, like our work, a review on physical exercise found most cost-effectiveness studies involved back conditions, osteoarthritis, and knee pain [10]. Single studies were also found for the musculoskeletal disorders of the shoulder and the neck [10].

That review [10] on physical exercise in the treatment of various diseases overlaps partly with our study. It includes 28 studies on musculoskeletal conditions of which we included 12 as well. However, the investigators focused on exercises as an intervention while we focused on treatments delivered by physiotherapists.

Interestingly, exercise was the most studied physiotherapeutic treatment in our work. Unfortunately, the treatments like exercise considered in our review were often combined with other treatments such as education, which often leaves the effectiveness of one specific treatment modality open. Furthermore, the treatments were rarely described sufficiently. For exercises e.g. they often lacked at least one dimension of frequency, intensity, time, and type of exercises e.g. aerobic vs. anaerobic or group vs individual therapy. Some articles even mentioned physiotherapy as provided treatment only. However, physiotherapy is not a treatment but a profession [99]. Consequently, several of the described interventions lack details, which leaves practitioners with the intention to implement cost-effective treatments with uncertainty and limits the ability to compare between different physiotherapeutic treatments.

The lack of provided details of the provided physiotherapeutic intervention is present in several studies and in clinical practice. Some initiatives aim to improve the documentation of provided treatments [100, 101]. However, they often apply to one specific treatment only such as exercises or the McKenzie treatment method [102]. Therefore, their applicability to other physiotherapeutic treatments is limited and therapists without special training sometimes do not understand the documentation. Hence, a specific but detailed documentation system for the provision of physiotherapeutic treatments is yet to the best of our knowledge missing.

Interestingly the provided treatments were similar across different body parts. This might suggest that the ideal treatment for a painful joint does not depend on the location. However, studies with more detailed treatment descriptions and with mixed population groups need to prove this hypothesis.

Future Research

The findings of our study indicate that there is a lack of economic evaluations for musculoskeletal conditions affecting joints other than the back and knee. Furthermore, conditions other than osteoarthritis such as fractures were rarely investigated and need further attention. Finally, systematic reviews of economic evaluations for physiotherapeutic treatments of back and knee complaints may be indicated, if not already covered by available reviews [103,104,105,106]. Additionally, a systematic review of the cost-effectiveness of preventive interventions could be interesting, since our focus was on studies dealing with patients with musculoskeletal conditions, thus excluding primary preventions.

Strength and Limitations

The major limitation of our study relates to the investigated interventions. First, defining the inclusion and exclusion criteria for an intervention was challenging. We aimed to include physiotherapeutic interventions, however, there is a large body of treatments such as tai chi, yoga, behavior change techniques, etc. which can be offered by physiotherapists but require further training. This training is open to non-health professionals as well. Some treatments e.g. behavior change techniques can also be offered by other health professionals who may be better qualified and thus more likely to provide a specific treatment. Furthermore, we decided to take a rather narrow approach regarding the inclusion criteria to ensure that the intervention was offered by physiotherapists. Second, we excluded conference abstracts, reviews, and model-based studies, which might involve the exclusion of relevant publications. Finally, our systematic search could have been broadened by additional search terms and the involvement of an additional database. This could have identified additional relevant publications since two of the included publications were only identified through the recommendation of experts in the field. The major strength of this overview is its transparency. Besides publishing a protocol and providing details on the conduct of our study and using the PRISMA statement, we also provide a list of the excluded full-text publications. The qualitative completeness of this review is underpinned by the quality evaluation of the individual articles and the provision of a cost-effectiveness plane. Consequently, we provide insights on the availability and quality of available articles and in this way highlight knowledge gaps in the literature.

Conclusions

Several high-quality trial-based economic evaluations of physiotherapeutic interventions for patients with musculoskeletal disorders exist and demonstrate cost-effectiveness. However, most articles address low back and knee conditions, and evaluations concerning other joints are limited. Finally, the documentation of provided interventions needs improvement to enable clinicians and stakeholders to fairly compare and finally to implement cost-effective treatments.

Availability of Data and Materials

All data involved data in this article are available online through the original articles. Where there is uncertainty, the authors are happy to provide details on the analyses on request.

Abbreviations

- QALY:

-

Quality-adjusted life-year

- RCT:

-

Randomized controlled trial

References

World Health Organization. Musculoskeletal health. 2022, 2023. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/musculoskeletal-conditions#:~:text=A%20recent%20analysis%20of%20Global,and%20rheumatoid%20arthritis%20(1). Accessed 7 Mar 2023.

Kapitel 5.3.2 Inanspruchnahme [Gesundheit in Deutschland, 2015], 2024. https://www.gbe-bund.de/gbe/abrechnung.prc_abr_test_logon?p_uid=gast&p_aid=0&p_knoten=FID&p_sprache=D&p_suchstring=25752. Accessed 10 Feb 2024.

Williams A, Kamper SJ, Wiggers JH, et al. Musculoskeletal conditions may increase the risk of chronic disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. BMC Med. 2018;16:1–9.

Björnsdóttir S, Jónsson S, Valdimarsdóttir U. Mental health indicators and quality of life among individuals with musculoskeletal chronic pain: a nationwide study in Iceland. Scand J Rheumatol. 2014;43(5):419–23.

Gesundheitsausgaben nach Leistungsarten. 2021; https://www.destatis.de/DE/Themen/Gesellschaft-Umwelt/Gesundheit/Gesundheitsausgaben/Tabellen/leistungsarten.html.

Turner HC, Archer RA, Downey LE, et al. An introduction to the main types of economic evaluations used for informing priority setting and resource allocation in healthcare: key features, uses, and limitations. Front Public Health. 2021;9:722927.

Grønne DT, Roos EM, Ibsen R, Kjellberg J, Skou ST. Cost-effectiveness of an 8-week supervised education and exercise therapy programme for knee and hip osteoarthritis: a pre–post analysis of 16 255 patients participating in good life with osteoArthritis in Denmark (GLA: D). BMJ Open. 2021;11(12):e049541.

Mazzei D, Ademola A, Abbott J, Sajobi T, Hildebrand K, Marshall D. Are education, exercise and diet interventions a cost-effective treatment to manage hip and knee osteoarthritis? A systematic review. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2021;29(4):456–70.

García-Álvarez D, Sempere-Rubio N, Faubel R. Economic evaluation in neurological physiotherapy: a systematic review. Brain Sci. 2021;11(2):265.

Roine E, Roine RP, Räsänen P, Vuori I, Sintonen H, Saarto T. Cost-effectiveness of interventions based on physical exercise in the treatment of various diseases: a systematic literature review. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2009;25(4):427–54.

Baumbach L, König H-H, Kretzler B, Hajek A. Economic evaluations of musculoskeletal physiotherapy: protocol of a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2022;12(2):e058143.

Evers S, Goossens M, De Vet H, Van Tulder M, Ament A. Criteria list for assessment of methodological quality of economic evaluations: consensus on health economic criteria. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2005;21(2):240–5.

Abbott JH, Wilson R, Pinto D, Chapple CM, Wright AA. Incremental clinical effectiveness and cost effectiveness of providing supervised physiotherapy in addition to usual medical care in patients with osteoarthritis of the hip or knee: 2-year results of the MOA randomised controlled trial. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2019;27(3):424–34.

Aboagye E, Karlsson ML, Hagberg J, Jensen I. Cost-effectiveness of early interventions for non-specific low back pain: a randomized controlled study investigating medical yoga, exercise therapy and self-care advice. J Rehabil Med. 2015;47(2):167–73.

Ankjaer-Jensen A, Manniche C, Nielsen H. [Postoperative rehabilitation of patients operated for lumbar disk prolapse. An analysis of the socioeconomic consequences]. Ugeskr Laeger. 1994;156(5):647–52.

Apeldoorn AT, Bosmans JE, Ostelo RW, de Vet HC, van Tulder MW. Cost-effectiveness of a classification-based system for sub-acute and chronic low back pain. Eur Spine J. 2012;21(7):1290–300.

Barker KL, Newman M, Stallard N, et al. Exercise or manual physiotherapy compared with a single session of physiotherapy for osteoporotic vertebral fracture: three-arm PROVE RCT. Health Technol Assess. 2019;23(44):1–318.

Barker KL, Room J, Knight R, et al. Outpatient physiotherapy versus home-based rehabilitation for patients at risk of poor outcomes after knee arthroplasty: CORKA RCT. Health Technol Assess. 2020;24(65):1–116.

Barnhoorn K, Staal JB, van Dongen RT, et al. Pain exposure physical therapy versus conventional treatment in complex regional pain syndrome type 1-a cost-effectiveness analysis alongside a randomized controlled trial. Clin Rehabil. 2018;32(6):790–8.

Barton GR, Sach TH, Jenkinson C, Doherty M, Avery AJ, Muir KR. Lifestyle interventions for knee pain in overweight and obese adults aged >=45: economic evaluation of randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2009;339:b2273.

Bello AI, Quartey J, Lartey M. Efficacy of behavioural graded activity compared with conventional exercise therapy in chronic non-specific low back pain: implication for direct health care cost. Ghana Med J. 2015;49(3):173–80.

Bennell KL, Ahamed Y, Jull G, et al. Physical therapist-delivered pain coping skills training and exercise for knee osteoarthritis: randomized controlled trial. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2016;68(5):590–602.

Bergman GJD, Winter JC, van Tulder MW, Meyboom-de Jong B, Postema K, van der Heijden GJMG. Manipulative therapy in addition to usual medical care accelerates recovery of shoulder complaints at higher costs: economic outcomes of a randomized trial. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2010;11:200.

Bosmans JE, Pool JJM, Vet HCWd, van Tulder MW, Ostelo RWJG. Is behavioral graded activity cost-effective in comparison with manual therapy for patients with subacute neck pain? An economic evaluation alongside a randomized clinical trial. Spine. 2011;36(18):E1179–86.

Bulthuis Y, Mohammad S, Braakman-Jansen LM, Drossaers-Bakker KW, van de Laar MA. Cost-effectiveness of intensive exercise therapy directly following hospital discharge in patients with arthritis: results of a randomized controlled clinical trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59(2):247–54.

Burton. United Kingdom back pain exercise and manipulation (UK BEAM) randomised trial: cost effectiveness of physical treatments for back pain in primary care. BMJ. 2004;329(7479):1381.

Canaway A, Pincus T, Underwood M, Shapiro Y, Chodick G, Ben-Ami N. Is an enhanced behaviour change intervention cost-effective compared with physiotherapy for patients with chronic low back pain? Results from a multicentre trial in Israel. BMJ Open. 2018;8(4):e019928.

Carr JL, Klaber Moffett JA, Howarth E, et al. A randomized trial comparing a group exercise programme for back pain patients with individual physiotherapy in a severely deprived area. Disabil Rehabil. 2005;27(16):929–37.

Cherkin DC, Deyo RA, Battié M, Street J, Barlow W. A comparison of physical therapy, chiropractic manipulation, and provision of an educational booklet for the treatment of patients with low back pain. N Engl J Med. 1998;339(15):1021–9.

Coombes BK, Connelly L, Bisset L, Vicenzino B. Economic evaluation favours physiotherapy but not corticosteroid injection as a first-line intervention for chronic lateral epicondylalgia: evidence from a randomised clinical trial. Br J Sports Med. 2015;50:1400–5.

Coupé VM, Veenhof C, van Tulder MW, Dekker J, Bijlsma JW, Van den Ende CH. The cost effectiveness of behavioural graded activity in patients with osteoarthritis of hip and/or knee. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66(2):215–21.

Critchley DJ, Ratcliffe J, Noonan S, Jones RH, Hurley MV. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of three types of physiotherapy used to reduce chronic low back pain disability: a pragmatic randomized trial with economic evaluation. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2007;32(14):1474–81.

Daker-White G, Carr AJ, Harvey I, et al. A randomised controlled trial. Shifting boundaries of doctors and physiotherapists in orthopaedic outpatient departments. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1999;53(10):643–50.

Denninger TR, Cook CE, Chapman CG, McHenry T, Thigpen CA. The influence of patient choice of first provider on costs and outcomes: analysis from a physical therapy patient registry. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2018;48(2):63–71.

Eggerding V, Reijman M, Meuffels DE, et al. ACL reconstruction for all is not cost-effective after acute ACL rupture. Br J Sports Med. 2021;56:24–8.

Fernandes L, Roos EM, Overgaard S, Villadsen A, Søgaard R. Supervised neuromuscular exercise prior to hip and knee replacement: 12-month clinical effect and cost-utility analysis alongside a randomised controlled trial. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2017;18(1):1–11.

Fernández-de-Las-Peñas C, Ortega-Santiago R, Díaz HF, et al. Cost-effectiveness evaluation of manual physical therapy versus surgery for carpal tunnel syndrome: evidence from a randomized clinical trial. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2019;49(2):55–63.

Fritz JM, Cleland JA, Speckman M, Brennan GP, Hunter SJ. Physical therapy for acute low back pain: associations with subsequent healthcare costs. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2008;33(16):1800–5.

Fritz JM, Kim M, Magel JS, Asche CV. Cost-effectiveness of primary care management with or without early physical therapy for acute low back pain: economic evaluation of a randomized clinical trial. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2017;42(5):285–90.

Fusco F, Campbell H, Barker K. Rehabilitation after resurfacing hip arthroplasty: cost-utility analysis alongside a randomized controlled trial. Clin Rehabil. 2019;33(6):1003–14.

Geraets JJXR, Goossens MEJB, Bruijn CPCd, et al. Cost-effectiveness of a graded exercise therapy program for patients with chronic shoulder complaints. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2006;22(1):76–83.

Griffin DR, Dickenson EJ, Achana F, et al. Arthroscopic hip surgery compared with personalised hip therapy in people over 16 years old with femoroacetabular impingement syndrome: UK FASHIoN RCT. Health Technol Assess (Winchester, England). 2022;26(16):1–236.

Hahne AJ, Ford JJ, Surkitt LD, et al. Individualized physical therapy is cost-effective compared with guideline-based advice for people with low back disorders. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2017;42(3):E169–76.

Heij W, Sweerts L, Staal JB, et al. Implementing a personalized physical therapy approach (Coach2Move) is effective in increasing physical activity and improving functional mobility in older adults: a cluster-randomized, stepped wedge trial. Phys Ther. 2022;102:138.

Herman PM, Szczurko O, Cooley K, Mills EJ. Cost-effectiveness of naturopathic care for chronic low back pain. Altern Ther Health Med. 2008;14(2):32–9.

Hlobil H, Uegaki K, Staal JB, de Bruyne MC, Smid T, van Mechelen W. Substantial sick-leave costs savings due to a graded activity intervention for workers with non-specific sub-acute low back pain. Eur Spine J. 2007;16(7):919–24.

Ho-Henriksson C-M, Svensson M, Thorstensson CA, Nordeman L. Physiotherapist or physician as primary assessor for patients with suspected knee osteoarthritis in primary care - a cost-effectiveness analysis of a pragmatic trial. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2022;23(1):260.

Hopewell S, Keene DJ, Heine P, et al. Progressive exercise compared with best-practice advice, with or without corticosteroid injection, for rotator cuff disorders: the GRASP factorial RCT. Health Technol Assess. 2021;25(48):1–158.

Huang SW, Chen PH, Chou YH. Effects of a preoperative simplified home rehabilitation education program on length of stay of total knee arthroplasty patients. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2012;98(3):259–64.

Hurley DA, Tully MA, Lonsdale C, et al. Supervised walking in comparison with fitness training for chronic back pain in physiotherapy: results of the SWIFT single-blinded randomized controlled trial (ISRCTN17592092). Pain. 2015;156(1):131–47.

Hurley MV, Walsh NE, Mitchell H, Nicholas J, Patel A. Long-term outcomes and costs of an integrated rehabilitation program for chronic knee pain: a pragmatic, cluster randomized, controlled trial. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2012;64(2):238–47.

Hurley MV, Walsh NE, Mitchell HL, et al. Economic evaluation of a rehabilitation program integrating exercise, self-management, and active coping strategies for chronic knee pain. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;57(7):1220–9.

James M, Stokes EA, Thomas E, Dziedzic K, Hay EM. A cost consequences analysis of local corticosteroid injection and physiotherapy for the treatment of new episodes of unilateral shoulder pain in primary care. Rheumatology. 2005;44(11):1447–51.

Jessep SA, Walsh NE, Ratcliffe J, Hurley MV. Long-term clinical benefits and costs of an integrated rehabilitation programme compared with outpatient physiotherapy for chronic knee pain. Physiotherapy. 2009;95(2):94–102.

Johnson RE, Jones GT, Wiles NJ, et al. Active exercise, education, and cognitive behavioral therapy for persistent disabling low back pain: a randomized controlled trial. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2007;32(15):1578–85.

Juhakoski R, Tenhonen S, Malmivaara A, Kiviniemi V, Anttonen T, Arokoski JP. A pragmatic randomized controlled study of the effectiveness and cost consequences of exercise therapy in hip osteoarthritis. Clin Rehabil. 2011;25(4):370–83.

Karjalainen K, Malmivaara A, Pohjolainen T, et al. Mini-intervention for subacute low back pain: a randomized controlled trial: LWW. Spine. 2003;28(6):533–40.

Kigozi J, Jowett S, Nicholls E, Tooth S, Hay EM, Foster NE. Cost-utility analysis of interventions to improve effectiveness of exercise therapy for adults with knee osteoarthritis: the BEEP trial. Rheumatol Adv Pract. 2018;2(2):rky1018.

Kim G, Kim WS, Kim TW, Lee YS, Lee H, Paik NJ. Home-based rehabilitation using smart wearable knee exercise device with electrical stimulation after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Medicine (Baltimore). 2020;99(20):e20256.

Knoop J, Esser J, Dekker J, de Joode JW, Ostelo RW, van Dongen JM. No evidence for stratified exercise therapy being cost-effective compared to usual exercise therapy in patients with knee osteoarthritis: economic evaluation alongside cluster randomized controlled trial. Braz J Phys Ther. 2023;27(1):100469.

Korthals-de Bos IB, Smidt N, van Tulder MW, et al. Cost effectiveness of interventions for lateral epicondylitis: results from a randomised controlled trial in primary care. Pharmacoeconomics. 2004;22:185–95.

Korthals-de Bos IBC, Hoving JL, van Tulder MW, et al. Cost effectiveness of physiotherapy, manual therapy, and general practitioner care for neck pain: economic evaluation alongside a randomised controlled trial. BMJ (Clin Res Ed). 2003;326(7395):911.

Leininger B, McDonough C, Evans R, Tosteson T, Tosteson AN, Bronfort G. Cost-effectiveness of spinal manipulative therapy, supervised exercise, and home exercise for older adults with chronic neck pain. Spine J. 2016;16(11):1292–304.

Lewis M, James M, Stokes E, et al. An economic evaluation of three physiotherapy treatments for non-specific neck disorders alongside a randomized trial. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2007;46(11):1701–8.

Lilje SC, Persson UB, Tangen ST, Kåsamoen S, Skillgate E. Costs and utilities of manual therapy and orthopedic standard care for low-prioritized orthopedic outpatients of working age: a cost consequence analysis. Clin J Pain. 2014;30(8):730–6.

Lin C-WC, Moseley AM, Haas M, Refshauge KM, Herbert RD. Manual therapy in addition to physiotherapy does not improve clinical or economic outcomes after ankle fracture. J Rehabil Med. 2008;40(6):433–9.

Manca A, Dumville JC, Torgerson DJ, et al. Randomized trial of two physiotherapy interventions for primary care back and neck pain patients: cost effectiveness analysis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2007;46(9):1495–501.

Manca A, Epstein DM, Torgerson DJ, et al. Randomized trial of a brief physiotherapy intervention compared with usual physiotherapy for neck pain patients: cost-effectiveness analysis. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2006;22(1):67–75.

McCarthy CJ, Mills PM, Pullen R, et al. Supplementation of a home-based exercise programme with a class-based programme for people with osteoarthritis of the knees: a randomised controlled trial and health economic analysis. Health Technol Assess. 2004;8(46):iii–iv, 1–61.

Mitchell C, Walker J, Walters S, Morgan AB, Binns T, Mathers N. Costs and effectiveness of pre- and post-operative home physiotherapy for total knee replacement: randomized controlled trial. J Eval Clin Pract. 2005;11(3):283–92.

Müller G, Pfinder M, Clement M, et al. Therapeutic and economic effects of multimodal back exercise: a controlled multicentre study. J Rehabil Med. 2019;51(1):61–70.

Niemistö L, Lahtinen-Suopanki T, Rissanen P, Lindgren K-A, Sarna S, Hurri H. A randomized trial of combined manipulation, stabilizing exercises, and physician consultation compared to physician consultation alone for chronic low back pain. Spine. 2003;28(19):2185–91.

Niemistö L, Rissanen P, Sarna S, Lahtinen-Suopanki T, Lindgren K-A, Hurri H. Cost-effectiveness of combined manipulation, stabilizing exercises, and physician consultation compared to physician consultation alone for chronic low back pain: a prospective randomized trial with 2-year follow-up: LWW. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2005;28(19):2185–91.

Pinto D, Robertson MC, Abbott JH, Hansen P, Campbell AJ. Manual therapy, exercise therapy, or both, in addition to usual care, for osteoarthritis of the hip or knee. 2: economic evaluation alongside a randomized controlled trial. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2013;21(10):1504–13.

Pryymachenko Y, Wilson R, Sharma S, Pathak A, Abbott JH. Are manual therapy or booster sessions worthwhile in addition to exercise therapy for knee osteoarthritis: Economic evaluation and 2-year follow-up of a randomized controlled trial. Musculoskelet Sci Pract. 2021;56:102439.

Rhon DI, Kim M, Asche CV, Allison SC, Allen CS, Deyle GD. Cost-effectiveness of physical therapy vs intra-articular glucocorticoid injection for knee osteoarthritis: a secondary analysis from a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(1):e2142709.

Rivero-Arias O, Gray A, Frost H, Lamb SE, Stewart-Brown S. Cost-utility analysis of physiotherapy treatment compared with physiotherapy advice in low back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2006;31(12):1381–7.

Sevick MA, Bradham DD, Muender M, et al. Cost-effectiveness of aerobic and resistance exercise in seniors with knee osteoarthritis. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2000;32(9):1534–40.

Sevick MA, Dunn AL, Morrow MS, Marcus BH, Chen GJ, Blair SN. Cost-effectiveness of lifestyle and structured exercise interventions in sedentary adults: results of project ACTIVE. Am J Prev Med. 2000;19(1):1–8.

Sevick MA, Miller GD, Loeser RF, Williamson JD, Messier SP. Cost-effectiveness of exercise and diet in overweight and obese adults with knee osteoarthritis. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2009;41(6):1167–74.

Skargren EI, Carlsson PG, Öberg BE. One-year follow-up comparison of the cost and effectiveness of chiropractic and physiotherapy as primary management for back pain: subgroup analysis, recurrence, and additional health care utilization. Spine. 1998;23(17):1875–83.

Skargren EI, Öberg BE, Carlsson PG, Gade M. Cost and effectiveness analysis of chiropractic and physiotherapy treatment for low back and neck pain: six-month follow-up. Spine. 1997;22(18):2167–77.

Smeets RJ, Severens JL, Beelen S, Vlaeyen JW, Knottnerus JA. More is not always better: cost-effectiveness analysis of combined, single behavioral and single physical rehabilitation programs for chronic low back pain. Eur J Pain. 2009;13(1):71–81.

Søgaard R, Bünger CE, Laurberg I, Christensen FB. Cost-effectiveness evaluation of an RCT in rehabilitation after lumbar spinal fusion: a low-cost, behavioural approach is cost-effective over individual exercise therapy. Eur Spine J. 2008;17(2):262–71.

Stan G, Orban H, Orban C. Cost effectiveness analysis of knee osteoarthritis treatment. Chirurgia (Bucur). 2015;110(4):368–74.

Struijs PA, Korthals-de Bos IB, van Tulder MW, van Dijk CN, Bouter LM, Assendelft WJ. Cost effectiveness of brace, physiotherapy, or both for treatment of tennis elbow. Br J Sports Med. 2006;40(7):637–43 (discussion 643).

Suni JH, Kolu P, Tokola K, et al. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of neuromuscular exercise and back care counseling in female healthcare workers with recurrent non-specific low back pain: a blinded four-arm randomized controlled trial. BMC Public Health. 2018;18(1):1376.

Tan SS, Teirlinck CH, Dekker J, et al. Cost-utility of exercise therapy in patients with hip osteoarthritis in primary care. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2016;24(4):581–8.

Tan SS, van Linschoten RL, van Middelkoop M, Koes BW, Bierma-Zeinstra SM, Koopmanschap MA. Cost-utility of exercise therapy in adolescents and young adults suffering from the patellofemoral pain syndrome. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2010;20(4):568–79.

van de Graaf VA, van Dongen JM, Willigenburg NW, et al. How do the costs of physical therapy and arthroscopic partial meniscectomy compare? A trial-based economic evaluation of two treatments in patients with meniscal tears alongside the ESCAPE study. Br J Sports Med. 2020;54(9):538–45.

van den Hout WB, Jong Zd, Munneke M, Hazes JMW, Breedveld FC, Vliet Vlieland TPM. Cost-utility and cost-effectiveness analyses of a long-term, high-intensity exercise program compared with conventional physical therapy in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;53(1):39–47.

van der Graaff SJ, Reijman M, Meuffels DE, Koopmanschap MA. Cost-effectiveness of arthroscopic partial meniscectomy versus physical therapy for traumatic meniscal tears in patients aged under 45 years. Bone Joint J. 2023;105(11):1177–83.

van der Roer N, van Tulder M, van Mechelen W, de Vet H. Economic evaluation of an intensive group training protocol compared with usual care physiotherapy in patients with chronic low back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2008;33(4):445–51.

van Dongen JM, Groeneweg R, Rubinstein SM, et al. Cost-effectiveness of manual therapy versus physiotherapy in patients with sub-acute and chronic neck pain: a randomised controlled trial. Eur Spine J. 2016;25(7):2087–96.

Whitehurst DG, Lewis M, Yao GL, et al. A brief pain management program compared with physical therapy for low back pain: results from an economic analysis alongside a randomized clinical trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;57(3):466–73.

Niemistö L, Rissanen P, Sarna S, Lahtinen-Suopanki T, Lindgren KA, Hurri H. Cost-effectiveness of combined manipulation, stabilizing exercises, and physician consultation compared to physician consultation alone for chronic low back pain: a prospective randomized trial with 2-year follow-up. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2005;30(10):1109–15.

Fernandes L, Roos EM, Overgaard S, Villadsen A, Søgaard R. Supervised neuromuscular exercise prior to hip and knee replacement: 12-month clinical effect and cost-utility analysis alongside a randomised controlled trial. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2017;18(1):5.

Brauer CA, Neumann PJ, Rosen AB. Trends in cost effectiveness analyses in orthopaedic surgery. Clin Orthop Relat Res®. 2007;457:42–8.

Jull G, Moore AP. Physiotherapy is not a treatment technique. Musculoskelet Sci Pract. 2021;56:102480.

Slade SC, Dionne CE, Underwood M, Buchbinder R. Consensus on exercise reporting template (CERT): explanation and elaboration statement. Br J Sports Med. 2016;50(23):1428–37.

Vreeman DJ, Taggard SL, Rhine MD, Worrell TW. Evidence for electronic health record systems in physical therapy. Phys Ther. 2006;86(3):434–46.

May S. Classification by McKenzie mechanical syndromes: a survey of McKenzie-trained faculty. J Manip Physiol Ther. 2006;29(8):637–42.

Andronis L, Kinghorn P, Qiao S, Whitehurst DG, Durrell S, McLeod H. Cost-effectiveness of non-invasive and non-pharmacological interventions for low back pain: a systematic literature review. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2017;15:173–201.

Miyamoto GC, Lin C-WC, Cabral CMN, van Dongen JM, van Tulder MW. Cost-effectiveness of exercise therapy in the treatment of non-specific neck pain and low back pain: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2019;53(3):172–81.

Pinto D, Robertson MC, Hansen P, Abbott JH. Cost-effectiveness of nonpharmacologic, nonsurgical interventions for hip and/or knee osteoarthritis: systematic review. Value Health. 2012;15(1):1–12.

Woods B, Manca A, Weatherly H, et al. Cost-effectiveness of adjunct non-pharmacological interventions for osteoarthritis of the knee. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(3):e0172749.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. No sources of funding were used to assist in the preparation of this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LB: conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing. WF: methodology, formal analysis, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing. BK: conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, writing—review and editing. AH: conceptualization, methodology, writing—review and editing. HHK: conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, writing—review and editing. All authors read and approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

No ethic approval was required for this review article. This review was registered at Prospero with the ID “CRD42021276050”.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflicts of interest with the content of this review.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

Details on the PubMed search.

Additional file 2.

Overview of excluded full text articles.

Additional file 3.

Evaluation of the study quality with the Consensus on Health Economic Criteria checklist.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Baumbach, L., Feddern, W., Kretzler, B. et al. Cost-Effectiveness of Treatments for Musculoskeletal Conditions Offered by Physiotherapists: A Systematic Review of Trial-Based Evaluations. Sports Med - Open 10, 38 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40798-024-00713-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40798-024-00713-9