Abstract

Background

Engaging in physical activity increases energy expenditure, reducing total body fat. Time spent in sedentary behaviours is associated with overweight and obesity, and adequate sleep duration is associated with improved body composition. This systematic review aimed to analyse the relationship between compliance with the 24-h movement guidelines and obesity indicators in toddlers, children and adolescents.

Methods

A systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted. PubMed, Web of Science and Scopus were searched from inception to December 2021. Cross-sectional and prospective studies that analysed the relationship between 24-h movement guidelines and overweight and obesity written in English, French, Portuguese or Spanish were included. PROSPERO registration number is CRD42022298316.

Results

The associations between meeting the 24-h movement guidelines and standardised body mass index were null in the two studies for toddlers. Seven studies analysed the relationship between compliance with the 24-h movement guidelines and overweight and obesity among preschool children. Of these seven studies, six found no association between compliance with 24-h movement guidelines and body composition. Among children and adolescents, 15 articles were analysed. Of these 15 studies, in seven, it was found that children and adolescents who meet the 24-h movement guidelines were more likely to have lower risks of overweight and obesity. The meta-analysis yielded a pooled OR = 0.80 (95% CI = 0.68 to 0.95, p = 0.012, I2 = 70.5%) in favour of compliant participants. Regarding participants’ age groups, compliance with 24-h movement guidelines seems to exert greater benefits on overweight and obesity indicators among children-adolescents (OR = 0.62, p = 0.008) compared to participants at preschool (OR = 1.00, p = 0.931) and toddlers (OR = 0.91, p = 0.853).

Conclusion

Most included studies have not observed a significant relationship between compliance with the 24-h movement guidelines and overweight and obesity in toddlers, children and adolescents.

Similar content being viewed by others

Key Points

-

There are no associations between meeting 24-h movement guidelines and overweight and obesity for toddlers and preschool children.

-

Among children and adolescents, the results are inconclusive. Some children and adolescents who met the 24-h movement guidelines were more likely to have lower risks of being overweight or obese.

Introduction

The health benefits of engaging in physical activity, getting the recommended amount of sleep and reducing sedentary behaviour, mainly screen time, are well documented [1]. Several recommendations regarding physical activity, sedentary behaviour and sleep duration for toddlers, children and adolescents are available in the literature [1,2,3,4]. In 2016, the 24-h movement guidelines for children and youth aged 5–17 years were published in Canada for the first time [5]. One year later, guidelines were published for the early (0–4) years [6]. Briefly, these 24-h recommendations state that toddlers and preschoolers should accumulate at least three hours of physical activity (for preschoolers, at least one hour should be at moderate to vigorous intensity), ≤ 1 h/ day of screen time and 10 to13 hours of sleep [5, 6]. Children and adolescents should accumulate at least one hour of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity, ≤ 2 h of recreational screen time and 9–11 h of sleep (5–13 years old) or 8–10 h of sleep (14–17 years old) [5, 6]. These recommendations are an advance on existing guidance for physical activity [1, 2, 7], screen time [3] and sleep duration [4] because they integrate three different behaviours in a single recommendation. Its acceptance in the scientific and professional community occurred quickly and it began to be adopted in several countries and regions, such as Australia, New Zealand, South Africa and the Pacific region [8].

One of the health benefits of children and adolescents engaging in physical activity is preventing or treating obesity [1, 9]. Daily physical activity increases energy expenditure, contributing to a negative caloric balance and naturally reducing total body fat [10]. On the other hand, time spent in sedentary behaviours, mainly screen time, is associated with overweight and obesity [10, 11]. More time spent on screens is associated with more meal episodes, usually high-calorie snacks, which can explain the relationship between screen time and overweight and obesity [12]. Reducing screen time is also a strategy to prevent overweight and obesity. In addition, adequate sleep duration is associated with improved body composition [13, 14]. Children and adolescents who sleep less than recommended are more likely to be obese [14]. This means that sleep time must be respected as a physiological need of the body and as a behaviour that prevents various mental [15] and metabolic diseases [16, 17].

Although there is some evidence that physical activity, screen time and sleep duration are individually related to overweight and obesity [17,18,19,20,21], there is still discussion about how these behaviours interact and impact overweight and obesity in different age groups. Over the last decade, researchers have begun investigating the simultaneous associations of these three behaviours with health indicators [17, 22,23,24]. A previous review concluded that meeting 24-h movement guidelines has implications for health [25]. Therefore, the present systematic review aimed to evaluate the results of published studies that analyse the relationship between compliance with the 24-h movement guidelines [5] and overweight and obesity in toddlers, children and adolescents.

Methods

Registration

Before starting, the review protocol was registered in the International Prospective Register of Ongoing Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) with ID number CRD42022298316. The developed protocol follows the standards for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses [26].

Eligibility Criteria

The population, interventions, comparisons, outcomes and study design (PICOS) [27] framework was used to identify the studies following the objectives of the systematic review. Articles were required to analyse the relationship between 24-h movement guidelines and overweight and obesity. The following eligibility criteria were applied:

Population

It was expected to identify studies involving toddlers (1–4 years), children (5–12 years) and adolescents (13–17 years).

Exposure (Intervention)

Studies were included if they had reported the three behaviours of the Canadian 24-h movement guidelines for children and youth: physical activity, time spent in sedentary behaviour, specifically screen time, and sleep time [5]. For physical activity, studies were included if its assessment was self-reported, reported by parents or device based. For the assessment of screen time, the included studies could have assessed it by self-report or parent reporting for toddlers and younger children. The included studies would have to assess the duration of time spent sleeping by self-report, parent reporting or device based.

Comparison

According to the aim of the systematic review, potential studies did not have to be experimental or case–control. For this reason, the comparator or control group was not required for inclusion.

Outcomes

Overweight and obesity indicators were the primary outcomes. The outcomes could be body fat percentage using bioelectrical impedance analysis, body mass index z-scores, waist circumference and/or waist-to-height ratio or other objective measures of body composition assessment (e.g. using DEXA or plethysmography).

Study Design

Studies were observational or experimental to be included in the review. Case studies were excluded. Within these study designs, there were no further restrictions.

Search Strategy

Articles published until 31 December 2022 were located by the authors using PubMed, Web of Science and Scopus databases. Keywords included combinations of: (obes* OR weight* OR overweight OR “body composition” OR fat* OR adiposity OR BMI OR body OR fitness*) AND (“24-Hour Movement” OR “Canadian guideline*” OR “physical activity guideline*” OR “physical activity recommendation*” OR “sedentary behaviour guideline*” OR “sedentary behavior guideline*” OR “sedentary behaviour recommendation*” OR “sedentary behavior recommendation*” OR “sleep guideline*” OR “sleep recommendation*” OR “screen time guideline*” OR “screen time recommendation*”). These terms were searched for the title and abstract of scientific articles. Additionally, the cross-referencing search was performed in the full-text read of potentially included articles.

To be included in the current review, articles were required to meet the following criteria: (1) analysed the relationship between 24-h movement guidelines and overweight and obesity and (2) written in English, French, Portuguese or Spanish languages. Articles from the grey literature were excluded.

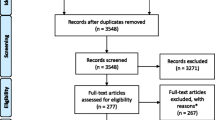

Study Selection

After searching each database, all studies were imported into Endnote 20, and duplicate records were eliminated. Two authors (AM and HS) analysed the titles and abstracts and selected the articles that would potentially enter the analysis. The same authors fully read all selected articles. There had to be a consensus for the articles to be included in the analysis. In the case of disagreement, an analysis was performed between the two authors (PM and EG), and a third author acted as moderator (VL). For an article to be excluded, it was necessary to present the reason.

Data Extraction

After defining the articles that would enter the analysis, an Excel form was created for data extraction. From each article, information was extracted on authorship, publication year, the country where the study was carried out, the methodological design, the sample characteristics, the instruments and procedures for the assessment of overweight and obesity indicators (outcome), physical activity, screen time and sleep (exposures) and the main conclusions. In addition, information was extracted on the prevalence of toddlers, children and adolescents who complied with the total recommendation and the prevalence of those who did not comply with the recommendation in any of the behaviours.

Methodological Quality Assessment

The methodological quality of the studies was assessed using the study quality assessment tool adapted from the National Institutes of Health/National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools). The quality of each reviewed study was reported as poor, fair or good. The methodological quality of the articles was evaluated by one reviewer (HS) and confirmed by the larger review team. Disagreements were resolved by discussion among the team members.

Quantitative Synthesis

The Comprehensive Meta-Analysis program (version 2; Biostat, Englewood, NJ, USA) was used. A minimum of three studies reporting the same outcome were required to perform the meta-analysis. The main outcome for the meta-analysis was overweight/obesity (e.g. BMI z-scores as a continuous outcome) relationship with 24-h movement guidelines compliance. Associations for weight status as a categorical outcome were not included.

To account for heterogeneity across studies, the weights of trials were proportional to their standard errors by applying an inverse variance using the DerSimonian and Laird random-effects model [28], computing meta-analyses reporting odd ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs). Heterogeneity was assessed using the I2 statistic, with values of < 25%, 25–75% and > 75% considered to represent low, moderate and high levels of heterogeneity, respectively [29].

Results

Literature Search

A flow diagram of citations summarising the systematic review process is displayed in Fig. 1. The systematic literature search yielded a total of 242 potentially relevant publications. Of these records, 81 were identified in PubMed, 79 in Scopus and 82 in Web of Science. After excluding duplicates (n = 125), 117 publications were screened for inclusion in the review. A total of 28 articles were rejected at the title and abstract levels because they did not meet the inclusion criteria. Consequently, 89 potentially relevant citations were obtained. From these 89 articles, 71 were eliminated after a complete reading. Reasons for excluding articles were: review article (n = 1), different outcomes than overweight and obesity (n = 13), isotemporal analysis (n = 1) and not reporting a combination of physical activity, screen time and sleep duration (n = 56). Eighteen articles were identified as relevant. In addition to the 18 articles, six more were identified through the bibliography of consulted articles. In the end, the number of articles was 24.

Study Characteristics

The study characteristics are summarised in Table 1. Of the 24 included articles, 20 were cross-sectional, two were prospective, one was a randomised controlled trial and one was cross-sectional and prospective. All studies were published in 2017 or later. The participants of two studies were toddlers [30, 31], seven studies were conducted among preschool children [13, 19, 32,33,34,35,36], and the other 15 included school-age children and adolescents. The number of study participants was 215,148 (353 toddlers, 6020 preschool children, 208,775 school-aged children and adolescents). The studies’ participants were from several different countries, two from Australia [31, 37], three from Canada [13, 30, 38], five from China (one from the mainland and two from Hong Kong) [18, 34, 39,40,41], one from the Czech Republic [42], one from Finland [35], two from Japan [19, 43], one from New Zealand [36], one from Spain [44], one from Sweden [32] and four from the USA [21, 45,46,47]. The remaining three studies analysed several countries: Belgium, Bulgaria, Germany, Greece, Poland and Spain [33]; Thailand, China, Malaysia, South Korea, Japan and Taiwan [48]; and Australia, Brazil, Canada, China, Colombia, Finland, India, Kenya, Portugal, South Africa, UK and USA [20].

The outcome variable for overweight and obesity was the body mass index z-score in 20 studies. Only two studies used body fat percentage to assess overweight and obesity, one via bioelectrical impedance analysis [48] and one via dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry [36]. Accelerometers or pedometers were used to assess physical activity in two studies with toddlers [30, 31], seven studies with preschool children [13, 19, 32,33,34,35,36] and seven studies with children and adolescents [20, 21, 37,38,39, 42, 43]. Self-reported physical activity was used in eight studies with children and adolescents [18, 40, 41, 44,45,46,47,48]. Screen time was reported by parents in the studies with toddlers and preschool children and self-reported in studies with adolescents. Parents reported sleep time in studies with toddlers and preschool children. Among children and adolescents, sleep time was self-reported in most studies. Parents reported sleep time in two studies [43, 44], and in one, it was only objectively measured [39].

None of the studies was considered to be of weak methodological quality. Six studies with children and adolescents were of fair quality [18, 38, 40, 41, 44, 48], and the other 18 were of good quality (Additional files 1 and 2). Most studies did not report whether the outcome was blinded to the exposure status of participants.

Main Findings

For toddlers, the associations between meeting the 24-h movement guidelines and body mass index z-score were null in both studies that analysed this relationship [30, 31].

Seven studies analysed the relationship between compliance with the 24-h movement guidelines and overweight and obesity among preschool children. Six studies found no association between meeting the 24-h movement guidelines and body mass index z-score [13, 32,33,34,35,36]. A non-significant association was also observed when body composition was assessed by waist circumference [35] or by dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry [36]. Only one study found that those who did not meet all the 24-h movement guidelines had higher odds of being overweight or obese than those who met the guidelines (OR = 1.14, 95% CI: 1.01, 1.29) [19].

Fifteen articles with school-age children and adolescents were analysed. Eight studies found that children and adolescents who met the 24-h movement guidelines were more likely to have lower risks of overweight and obesity [18, 20, 21, 37, 40, 41, 46, 47]. Six articles showed no differences in overweight and obesity levels in children and adolescents who comply and do not comply with all 24-h movement guidelines [39, 42,43,44,45, 48]. In one of the articles, the analyses were stratified by age, analysing children, early adolescents and adolescents [38]. The results were mixed, verifying a significant relationship between non-compliance with any recommendation and body mass index among children aged 8 to 10. However, no significant results were observed when analysing the relationship between non-compliance with any recommendation and body fat percentage.

The meta-analysis included 12 studies. Of 14 comparisons, 11 favoured compliant participants and three were statistically significant (p = 0.028 to < 0.001). The effects were fairly consistent, with the 95% CI for 11 out of 14 comparisons overlapping the mean, and a pooled OR = 0.80 (95% CI = 0.68 to 0.95, p = 0.012, I2 = 70.5%) (Fig. 2).

Regarding participants’ age groups, compliance with guidelines seems to exert greater benefits on overweight and obesity indicators among children-adolescents (OR = 0.62, CI = 0.43 to 0.88, I2 = 78.3%; p = 0.008; Fig. 3) compared to participants at preschool (OR = 1.00, CI = 0.93–1.08, I2 = 0.0%; p = 0.931; Fig. 4) and toddlers (OR = 0.91, CI = 0.33 to 2.51, I2 = 33.0%; p = 0.853; Fig. 5).

Discussion

This systematic review synthesised evidence from 24 articles examining the association between compliance with 24-h movement guidelines and overweight and obesity indicators among toddlers, preschool children, school-aged children and adolescents. Individually, physical activity, reduced screen time and sleep time seem to be related to obesity [11, 49]. As a result, it would be expected that the same would be observed when the three behaviours were combined. However, this was not the case in most studies. The findings indicate no associations between meeting 24-h movement guidelines and overweight and obesity for toddlers. However, only two articles were analysed, so care must be taken in interpreting these data. Generally, the results for preschool children showed no associations between meeting 24-h movement guidelines and being overweight or obese, except in one study [19]. For school-aged children and adolescents, the results were mixed. In most studies, no association was observed, but in eight studies, children and adolescents who met the 24-h movement guidelines were more likely to have lower risks of overweight and obesity [18, 20, 21, 37, 40, 41, 46, 47]. The meta-analysis indicated a favouring effect for guideline compliance, particularly among children and adolescents.

Neither individual movement nor combinations of behaviours were associated with overweight or obesity indicators for toddlers. Although these results are not theoretically expected, they align with previous studies [25]. Although most toddlers meet the physical activity recommendations [7], there were no significant relationships between physical activity and the body mass index in the two studies analysed [30, 31]. Furthermore, there were no significant relationships between full compliance with the 24-h movement guidelines and the body mass index. The main determinants of overweight and obesity for these ages are dietary factors (behavioural determinants) [50]. Thus, it is understandable that compliance with the 24-h movement guidelines may not significantly correlate with the body mass index.

Among preschool children, most studies did not indicate an association between compliance with the 24-h movement guidelines and overweight and obesity [13, 32,33,34,35,36]. However, one study did show that children who failed to meet the guidelines had a higher probability of obesity than those who met the guidelines [19]. In addition to this study, two others showed that compliance with certain individual recommendations was related to reducing adiposity [33, 35]. Nevertheless, the results are so different that a conclusion is unfeasible. For example, one study showed that meeting physical activity and sleep recommendations was associated with reducing adiposity [35]. Another study indicates that meeting the screen time recommendation alone reduces adiposity [33]. A possible explanation for these different results may be related to the fact that preschool children are very young and the impact of these behaviours on body composition is still not felt. Furthermore, recommendations for screen time may not be directly linked to overweight and obesity because the mere fact that a child is watching television, or using another device with a screen, does not increase total body fat. For this to happen, there must be another complementary action usually related to food intake. At younger ages, parents control food intake more [51], which may explain the absence of a significant relationship.

Individually, physical activity, reduced screen time and sleep time seem to be related to overweight and obesity in childhood and adolescence [11, 14, 49]. Nevertheless, for school-aged children and adolescents, the results were mixed. There was no association between compliance with the 24-h movement guidelines and overweight and obesity in most studies [38, 39, 42,43,44,45, 48]. In eight studies, children and adolescents who comply with the 24-h movement guidelines were less likely to be overweight or obese [18, 20, 21, 37, 40, 41, 46, 47]. In these studies, it was clear that physical activity was the behaviour that seemed to contribute most to the reduction of adiposity [20, 47]. These results align with previous investigations that sought to analyse the relationship between health indicators and the three behaviours that comprise the 24-h movement guidelines [23].

Mixed results, or the lack of a significant relationship between compliance with the 24-h movement guidelines and overweight and obesity, may be related to the fact that few toddlers, children and adolescents comply with the recommendations. One of the reasons why most toddlers, children and adolescents do not comply with the 24-h movement recommendations is the low prevalence of meeting the physical activity guidelines [52, 53]. Children and adolescents who meet the recommendations for physical activity improve cardiorespiratory fitness, musculoskeletal fitness, cardiometabolic health, motor skills, cognitive functions and academic outcomes and are less likely to experience depression [1, 9]. Although there are favourable associations between physical activity and reductions in overweight and obesity, the results are mixed [54]. It seems that going beyond the recommended physical activity levels is needed to affect adiposity in children. Isotemporal analyses showed that reducing sedentary time and increasing physical activity can reduce adiposity [55].

We acknowledged some limitations of this systematic review. First, most studies included were cross-sectional. This study design precluded conclusions regarding causality between movement behaviours and weight status or obesity. Second, in most studies, parents or teens reported sleep time. This information is based on when they went to bed and woke up. It is impossible to guarantee that toddlers, children and adolescents slept for all this reported time. Third, screen time was also reported, as there is not yet an instrument capable of measuring this time objectively. For teenagers, time on cell phone screens may not have been quantified. Fourth, several studies did not use representative population samples for the ages studied, making it difficult to generalise the results. Five studies not written in the English, French, Portuguese or Spanish languages were not included. For an in-depth understanding of these relationships, future studies may also benefit from including dietary behaviours and recommendations in their analysis.

Conclusion

Most included studies have not observed a significant relationship between compliance with the 24-h movement guidelines and overweight and obesity in toddlers, children and adolescents. This is more evident in toddlers and preschool children. Two elements are critically needed to understand better the relationship between compliance with the 24-h movement guidelines and overweight and obesity: future longitudinal research design and the integration of more accurate methodologies to assess screen time and sleep time (including technological sensors).

Availability of Data and Materials

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

USDHHS. 2018 Physical activity guidelines advisory committee scientific report. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2018.

WHO. WHO guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020.

Hirshkowitz M, Whiton K, Albert SM, Alessi C, Bruni O, DonCarlos L, et al. National Sleep Foundation’s updated sleep duration recommendations: final report. Sleep Health. 2015;1(4):233–43.

American Academy of Pediatrics. American Academy of Pediatrics: Children, adolescents, and television. Pediatrics. 2001;107(2):423–6.

Tremblay MS, Carson V, Chaput JP, Connor Gorber S, Dinh T, Duggan M, et al. Canadian 24-hour movement guidelines for children and youth: an integration of physical activity, sedentary behaviour, and sleep. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2016;41(6 Suppl 3):S311–27.

Tremblay MS, Chaput JP, Adamo KB, Aubert S, Barnes JD, Choquette L, et al. Canadian 24-hour movement guidelines for the early years (0–4 years): an integration of physical activity, sedentary behaviour, and sleep. BMC Public Health. 2017;17(Suppl 5):874.

WHO. WHO guidelines on physical activity, sedentary behaviour and sleep for children under 5 years of age. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2019.

Loo BKG, Okely AD, Pulungan A, Jalaludin MY, Asia-Pacific 24-Hour Activity Guidelines for C, Adolescents C. Asia-Pacific Consensus Statement on integrated 24-hour activity guidelines for children and adolescents. Br J Sports Med. 2022;56(10):539–45.

Poitras VJ, Gray CE, Borghese MM, Carson V, Chaput JP, Janssen I, et al. Systematic review of the relationships between objectively measured physical activity and health indicators in school-aged children and youth. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2016;41(6 Suppl 3):S197-239.

McCormack L, Meendering J, Specker B, Binkley T. Associations between sedentary time, physical activity, and dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry measures of total body, android, and gynoid fat mass in children. J Clin Densitom. 2016;19(3):368–74.

Mineshita Y, Kim HK, Chijiki H, Nanba T, Shinto T, Furuhashi S, et al. Screen time duration and timing: effects on obesity, physical activity, dry eyes, and learning ability in elementary school children. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):422.

Bornhorst C, Wijnhoven TM, Kunesova M, Yngve A, Rito AI, Lissner L, et al. WHO European Childhood Obesity Surveillance Initiative: associations between sleep duration, screen time and food consumption frequencies. BMC Public Health. 2015;30(15):442.

Chaput JP, Colley RC, Aubert S, Carson V, Janssen I, Roberts KC, et al. Proportion of preschool-aged children meeting the Canadian 24-Hour Movement Guidelines and associations with adiposity: results from the Canadian Health Measures Survey. BMC Public Health. 2017;17(Suppl 5):829.

Miller MA, Kruisbrink M, Wallace J, Ji C, Cappuccio FP. Sleep duration and incidence of obesity in infants, children, and adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Sleep. 2018;41(4).

Horiuchi F, Kawabe K, Oka Y, Nakachi K, Hosokawa R, Ueno SI. Mental health and sleep habits/problems in children aged 3–4 years: a population study. Biopsychosoc Med. 2021;15(1):10.

Golshevsky DM, Magnussen C, Juonala M, Kao KT, Harcourt BE, Sabin MA. Time spent watching television impacts on body mass index in youth with obesity, but only in those with shortest sleep duration. J Paediatr Child Health. 2020;56(5):721–6.

Whiting S, Buoncristiano M, Gelius P, Abu-Omar K, Pattison M, Hyska J, et al. Physical activity, screen time, and sleep duration of children aged 6–9 years in 25 countries: an analysis within the WHO European Childhood Obesity Surveillance Initiative (COSI) 2015–2017. Obes Facts. 2021;14(1):32–44.

Chen ST, Liu Y, Tremblay MS, Hong JT, Tang Y, Cao ZB, et al. Meeting 24-h movement guidelines: prevalence, correlates, and the relationships with overweight and obesity among Chinese children and adolescents. J Sports Health Sci. 2021;10(3):349–59.

Kim H, Ma J, Harada K, Lee S, Gu Y. Associations between adherence to combinations of 24-h movement guidelines and overweight and obesity in Japanese preschool children. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(24):1–11.

Roman-Viñas B, Chaput JP, Katzmarzyk PT, Fogelholm M, Lambert EV, Maher C, et al. Proportion of children meeting recommendations for 24-hour movement guidelines and associations with adiposity in a 12-country study. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2016;13(1).

Laurson KR, Lee JA, Gentile DA, Walsh DA, Eisenmann JC. Concurrent associations between physical activity, screen time, and sleep duration with childhood obesity. ISRN Obes. 2014;2014: 204540.

Chastin SF, Palarea-Albaladejo J, Dontje ML, Skelton DA. Combined effects of time spent in physical activity, sedentary behaviors and sleep on obesity and cardio-metabolic health markers: a novel compositional data analysis approach. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(10): e0139984.

Saunders TJ, Gray CE, Poitras VJ, Chaput J-P, Janssen I, Katzmarzyk PT, et al. Combinations of physical activity, sedentary behaviour and sleep: relationships with health indicators in school-aged children and youth. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2016;41(6 (Suppl. 3)):S283–S93.

Carson V, Tremblay MS, Chastin SFM. Cross-sectional associations between sleep duration, sedentary time, physical activity, and adiposity indicators among Canadian preschool-aged children using compositional analyses. BMC Public Health. 2017;17(Suppl 5):848.

Rollo S, Antsygina O, Tremblay MS. The whole day matters: understanding 24-hour movement guideline adherence and relationships with health indicators across the lifespan. J Sports Health Sci. 2020;9(6):493–510.

Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev. 2015;01(4):1.

Schardt C, Adams MB, Owens T, Keitz S, Fontelo P. Utilization of the PICO framework to improve searching PubMed for clinical questions. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2007;15(7):16.

Kontopantelis E, Springate DA, Reeves D. A re-analysis of the Cochrane Library data: the dangers of unobserved heterogeneity in meta-analyses. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(7): e69930.

Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21(11):1539–58.

Lee EY, Hesketh KD, Hunter S, Kuzik N, Rhodes RE, Rinaldi CM, et al. Meeting new Canadian 24-Hour Movement Guidelines for the Early Years and associations with adiposity among toddlers living in Edmonton, Canada. BMC Public Health. 2017;17(Suppl 5):840.

Santos R, Zhang Z, Pereira JR, Sousa-Sá E, Cliff DP, Okely AD. Compliance with the Australian 24-hour movement guidelines for the early years: associations with weight status. BMC Public Health. 2017;17(Suppl 5):867.

Berglind D, Ljung R, Tynelius P, Brooke HL. Cross-sectional and prospective associations of meeting 24-h movement guidelines with overweight and obesity in preschool children. Pediatr Obes. 2018;13(7):442–9.

Decraene M, Verbestel V, Cardon G, Iotova V, Koletzko B, Moreno LA, et al. Compliance with the 24-hour movement behavior guidelines and associations with adiposity in european preschoolers: results from the toybox-study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(14).

Feng J, Huang WY, Reilly JJ, Wong SHS. Compliance with the WHO 24-h movement guidelines and associations with body weight status among preschool children in Hong Kong. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2021;46(10):1273–8.

Leppänen MH, Ray C, Wennman H, Alexandrou C, Saaksjarvi K, Koivusilta L, et al. Compliance with the 24-h movement guidelines and the relationship with anthropometry in Finnish preschoolers: the DAGIS study. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):1618.

Meredith-Jones K, Galland B, Haszard J, Gray A, Sayers R, Hanna M, et al. Do young children consistently meet 24-h sleep and activity guidelines? A longitudinal analysis using actigraphy. Int J Obes (Lond). 2019;43(12):2555–64.

Hinkley T, Timperio A, Watson A, Duckham RL, Okely AD, Cliff D, et al. Prospective associations with physiological, psychosocial and educational outcomes of meeting Australian 24-Hour Movement Guidelines for the Early Years. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2020;17(1):36.

Chemtob K, Reid RER, Guimarães RDF, Henderson M, Mathieu ME, Barnett TA, et al. Adherence to the 24-hour movement guidelines and adiposity in a cohort of at risk youth: A longitudinal analysis. Pediatr Obes. 2021;16(4).

Shi Y, Huang WY, Sit CHP, Wong SHS. Compliance with 24-hour movement guidelines in Hong Kong adolescents: associations with weight status. J Phys Act Health. 2020;17(3):287–92.

Yang Y, Yuan S, Liu Q, Li F, Dong Y, Dong B, et al. Meeting 24-hour movement and dietary guidelines: prevalence, correlates and association with weight status among children and adolescents: a national cross-sectional study in China. Nutrients. 2022;14(14).

Zhou L, Liang W, He Y, Duan Y, Rhodes RE, Liu H, et al. Relationship of 24-hour movement behaviors with weight status and body composition in Chinese primary school children: a cross-sectional study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(14).

Jakubec L, Gába A, Dygrýn J, Rubín L, Šimůnek A, Sigmund E. Is adherence to the 24-hour movement guidelines associated with a reduced risk of adiposity among children and adolescents? BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):1119.

Tanaka C, Tremblay MS, Okuda M, Inoue S, Tanaka S. Proportion of Japanese primary school children meeting recommendations for 24-h movement guidelines and associations with weight status. Obesity research & clinical practice. 2020;14(3):234–40.

Suarez AP, Lomban BN, Cuadrado-Soto E, Sanchez JMP, Rodriguez LGG, Ortega RM. Weight status, body composition, and diet quality of Spanish schoolchildren according to their level of adherence to the 24-hour movement guidelines. Nutr Hosp. 2021;38(1):73–84.

Haegele JA, Zhu X, Healy S, Patterson F. The 24-hour movement guidelines and body composition among youth receiving special education services in the United States. J Phys Act Health. 2021;18(7):838–43.

Katzmarzyk PT, Staiano AE. Relationship between meeting 24-hour movement guidelines and cardiometabolic risk factors in children. J Phys Act Health. 2017;14(10):779–84.

Zhu X, Healy S, Haegele JA, Patterson F. Twenty-four-hour movement guidelines and body weight in youth. J Pediatr. 2020;218:204–9.

Hui SSC, Zhang R, Suzuki K, Naito H, Balasekaran G, Song JK, et al. The associations between meeting 24-hour movement guidelines and adiposity in Asian Adolescents: The Asia-Fit Study. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2021;31(3):763–71.

Marques A, Minderico C, Martins S, Palmeira A, Ekelund U, Sardinha LB. Cross-sectional and prospective associations between moderate to vigorous physical activity and sedentary time with adiposity in children. Int J Obes (Lond). 2016;40(1):28–33.

Lindkvist M, Ivarsson A, Silfverdal SA, Eurenius E. Associations between toddlers’ and parents’ BMI, in relation to family socio-demography: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2015;15(1):1252.

Marlene M, Marianne M, Liv Elin T. Association between parental feeding practices and children’s dietary intake: a cross-sectional study in the Gardermoen Region, Norway. Food Nutr Res. 2022;66.

Guthold R, Stevens GA, Riley LM, Bull FC. Global trends in insufficient physical activity among adolescents: a pooled analysis of 298 population-based surveys with 1.6 million participants. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2020;4(1):23–35.

Marques A, Henriques-Neto D, Peralta M, Martins J, Demetriou Y, Schonbach DMI, et al. Prevalence of physical activity among adolescents from 105 low, middle, and high-income countries. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(9).

Collins H, Fawkner S, Booth JN, Duncan A. The effect of resistance training interventions on weight status in youth: a meta-analysis. Sports Med Open. 2018;4(1):41.

Loprinzi PD, Cardinal BJ, Lee H, Tudor-Locke C. Markers of adiposity among children and adolescents: implications of the isotemporal substitution paradigm with sedentary behavior and physical activity patterns. J Diabetes Metab Disord. 2015;14:46.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

No sources of funding were used to assist in the preparation of this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AM and PM conceived the study. AM, PM and HS developed a systematic review protocol. AM, HS, EG, PM and VL conducted the literature search and selected the studies based on the title and the abstract and extracted and coded the data from all studies. Study outcomes were summarised by AM, GF, VL and JM. AM, PM, RT and RRC wrote the initial draft of the manuscript, and GF and JM made significant revisions and contributions. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

Adilson Marques, Rodrigo Ramirez-Campillo, Élvio Gouveia, Gerson Ferrari, Riki Tesler, Priscila Marconcin, Vânia Loureiro, João Martins and Hugo Sarmento declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Table S1.

Canadian guidelines according to age groups.

Additional file 2: Table S2.

Studies bias assessment using the NIH quality assessment tool for observational cohort and cross-sectional studies.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Marques, A., Ramirez-Campillo, R., Gouveia, É.R. et al. 24-h Movement Guidelines and Overweight and Obesity Indicators in Toddlers, Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sports Med - Open 9, 30 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40798-023-00569-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40798-023-00569-5