Abstract

Background

Many pregnancies in the United States are associated with maternal calorie overconsumption. Few data exist that track the impact of maternal and offspring calorie consumption on the risks for obesity development.

Methods

To determine the effects of maternal calorie intake during gestation on programming for adiposity in the offspring, pregnant gilts were fed either a normal (NE) or high (HE) energy diet to induce higher than normal (30 % increase) pregnancy weight gain and the profile of genes related to adipose tissue development was determined in the subcutaneous adipose tissue of the offspring. Gilts were fed the same lactation diet after farrowing and piglets were allowed to suckle from their mothers. Offspring were also fed either a normal energy (NE) or a high energy (HE) diet after weaning (3 weeks of age). Offspring were sacrificed at 48 h, 3 weeks and 3 months of age and the subcutaneous adipose tissue obtained for gene expression analysis by RT-PCR.

Results

Gilts on the HE diet had higher pregnancy weight gain and backfat thickness than those on the NE diet. Expression of adipogenic genes, such as peroxisome proliferator activated receptor (PPAR) γ and CCAAT enhancer binding protein (CEBP) α was not different between offspring from NE and HE mothers at 48 h after birth, but they were higher (P < 0.05) at 3 weeks in the offspring from HE mothers than NE. Steroid receptor coactivator 1 (SRC1) expression was higher in HE offspring at 48 h, but not different at weaning (P < 0.05). Inhibitors of wnt signaling, soluble frizzled related protein (SFRP) 4 and 5 were also higher in HE offspring at 3 weeks. The expression of PPARγ corepressors, sirtuin 1 (Sirt1, NAD-dependent deacetylase sirtuin-1) and nuclear receptor co-repressor 1 (NCoR1), was higher (P < 0.05) in HE offspring at weaning. At 3 months, there were no effects of maternal diets on offspring adipose tissue gene expression pattern, but animals on the postweaning HE diet had a higher (P < 0.05) expression of SFRP5, WNT5a, lower SFRP5/WNT5a and TNFα.

Conclusions

Effects of maternal calorie consumption on adipose tissue genes in the early postnatal life was transient in this study. Postweaning diet was more effective in changing offspring adipose tissue gene expression pattern and adiposity in the early postnatal period.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Many pregnancies in the US are associated with maternal gestational weight gain (GWG) in excess of recommendations. This is linked with an increased risk for larger for gestational age (LGA) offspring [1–3]. The effects of maternal GWG persist into early childhood and are associated with childhood adiposity, a risk of the offspring being overweight at multiple ages [4–7]. Greater offspring fat mass, a more direct measure of childhood adiposity, is found to be associated with excessive GWG. Excessive maternal weight gain directly affects gene expression pattern in adipose tissue, and high GWG leads to increased circulating concentrations of leptin and interleukin-6 [7], two cytokines that are highly expressed in adipose tissue, and tied to regulation of appetite and inflammation status respectively.

Currently one in five women are considered obese [8]. Pregnancy concurrent with obesity results in an altered intrauterine environment and poses a challenge for both the mother and fetus [9]. Maternal obesity leads to offspring with more subcutaneous fat tissue and elevated serum triglycerides, leptin and insulin despite the lack of effect maternal obesity on offspring body weight [10]. This early metabolic programming can persist to adulthood resulting in a phenotype that closely resembles the metabolic syndrome [11], manifested in abnormal glucose homeostasis [12], increased blood pressure [13], abnormal serum lipid profiles [10], increased adiposity [10], hyperphagia [12] and leptin resistance [14]. At present, the mechanism of adipose tissue programming in the offspring of obese mothers or mothers with excessive GWG is not known. This is partly because of methodological and ethical issues associated with conducting this type of research in human infants, and the lack of substantial adipose tissue in rodent pups. The pig is an excellent animal model for determining effects of maternal nutrition on adipose tissue programming because, unlike the rodent pup, the piglet has substantial adipose tissue at birth, weaning and at adulthood.

In Arentson-Lantz et al., 2014 [15] we presented liver and intestinal effects of maternal gestational calorie consumption. We hypothesized that maternal high energy intake would lead to programming of offspring for increased adiposity, which would be reflected in the gene expression pattern in adipose tissue, and that postweaning environment would temper the effect of maternal diets. Therefore, because of the potential for changes within adipose tissue of the offspring as a function of maternal diets, this work was conducted with the aim of investigating the effect maternal calorie consumption during gestation on offspring adiposity and adipose tissue programming.

Methods

Animals and diets

This study was carried out in strict accordance with the recommendations in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the National Institutes of Health. The Purdue Animal Care and Use Committee (PACUC) approved all procedures on care and use of pigs described in this study. Diets and animal care are as reported in Arentson-Lantz et al. [15]. Briefly, crossbred gilts (Landrace x Yorkshire terminal cross) kept at the Purdue University Animal Sciences Research and Education Center were assigned to two gestational diets; a normal energy diet (NE, n = 9) or a high energy diet (HE, n = 5) diet. Diets are as presented in Tables 1 and 2 and in Arentson-Lantz et al. 2014 [15]. All diets met the National Research Council Requirements for Swine (1998). As commonly practiced in the in the industry, gilts were limit-fed such that those on the NE diet received 2.05 kg of feed per day, the HE animals received 3.0 kg but with uninterrupted access to water. The HE diet supplied 50 % more metabolizable energy than the NE diet. Backfat at the 12th rib was measured at the end of gestation using ultra sound technique (Aloka American Ltd, Wallington, CT). Serum samples were collected from the gilts on days 21 (baseline), 44 and 77 of gestation. Whole blood was centrifuged at 4 °C at 3000 rpm for 15 min for collection of serum. Serum blood glucose concentration was determined with an automatic glucometer (Freestyle, Alameda, CA). Serum free fatty acid was determined using the free fatty acids, half micro test kit (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN). Serum insulin was determined using the Mercodia porcine insulin ELISA kit (Mercodia, Uppsala, Sweden) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Post-farrowing treatments

At farrowing, all gilts were fed the same lactation diet (Table 2). Piglet offspring were weaned on day 21. Immediately after weaning, piglets were kept on a common diet for 7 days after which they were assigned either to a post-weaning normal energy diet (NE) or high energy diet (HE) (Table 2). All piglets were kept in pens within an environmentally controlled house. A total of eighteen piglets from NE gilts were assigned to post-weaning diets (10 to NE and 8 to HE). Twelve piglets from the HE gilts were assigned (6 each NE and HE) to post-weaning diets (Fig. 1). Body weights of piglets was taken weekly during the grower phase and biweekly during the finisher phase. Equal number of males and female piglets were assigned to each treatment.

Study design. Pregnant gilts were assigned either to a normal energy (NE, n = 9) or a high energy diet (HE, n = 5) diet throughout gestation. After birth(farrowing), piglets stayed with their moms throughout lactation period (21 days after birth). After weaning on day 21, piglets were assigned to postweaning diets. A total of eighteen piglets from NE gilts were assigned to post-weaning diets (10 to NE and 8 to HE). Twelve piglets from the HE gilts were assigned (6 each NE and HE) to post-weaning diets

Sample collection

Milk was collected from sows at day 14 of lactation. Sows were given 10 IU of oxytocin via intramuscular route to stimulate milk let-down. Milk was manually expressed by a trained operator. Samples were sent to a commercial laboratory (Dairy One, Ithaca, NY) and analyzed for fats, solids and energy. To conduct gene expression analysis of piglet tissues, piglets were killed at each collection period (48 h, 3 weeks and 12 weeks) either with intramuscular injection of atropine, tiletamine-zolazepam, and xylazine followed by pneumothorax and cardiectomy or by CO2 exposure followed by severance of the jugular vein and exsanguination. This ensured pain to animals was minimized before death. Subcutaneous adipose tissue samples were collected from above the shoulders. Serum samples were collected at each of these time points. Samples were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and in −80 °C freezer for long-term storage for RNA extraction and RT-PCR. Piglet backfat thickness was manually measured immediately after euthanasia at 12 weeks above the shoulder (interscapular region) along the midline of the split carcass [16]. To allow consistency, this was done by a single operator.

RNA isolation and cDNA synthesis

After the isolation of RNA with the QIAzol reagent, it was dissolved in nuclease free water (Ambion, Austin, TX) and concentrations were determined using a Nanodrop reader (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA). RNA samples were subjected to electrophoresis on a 1 % agarose gel as a check of RNA integrity. One microgram of total RNA was reverse transcribed with MMLV reverse transcriptase (Promega, Madison, WI).

Real-time PCR analysis

Real-time quantitative PCR was performed using the MyiQ real-time PCR detection system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) using the SYBR mix RT-PCR mix (SABiosciences, Frederic, MD). The mRNA abundance of different genes was determined from the threshold cycle (Ct) for the respective genes and normalized against the Ct for 18S using the ΔΔCt method. Primers used for RT-PCR are listed in Table 5.

Data analysis

Data were examined for normality and analyzed using the GLM procedure (SAS Inst. Inc., Cary, NC). When there was significant main effect, separation of means was accomplished with the Tukey mean separation procedure. Differences were considered significant at P < 0.05 and at P < 0.10 for tendency towards significance. Values in texts are means ± SEM.

Results

Maternal responses

The maternal growth responses show that gilts on the HE diet gained significantly more (37 %) weight than those on the NE diet (41.9 vs. 29.6 kg). This was well within our expected 30 % more weight gain in gilts on the HE diet. Backfat accumulation was also higher in gilts on the HE diet than NE (7.6 vs. 4.30 mm) [15]. Thus the increased weight gain in gilts on the HE diet was associated with increased adiposity. Thus this model recapitulates the excessive gestational weight gain and adiposity in some pregnant women in the US. Serum glucose was also significantly higher in HE gilts (88.8 vs. 78.6 mg/dl) (P < 0.05), but the concentrations of insulin and NEFA were not affected by diet. In addition, milk from the HE gilts had a higher concentration of fat (8.79 vs. 7.2 %), solids (19.9 vs. 18.2 %) and energy (502 vs. 443 KJ/g) than from NE gilts [15]. Thus gestational HE intake resulted in milk with higher nutrient content than consumption of the NE diet.

Offspring responses

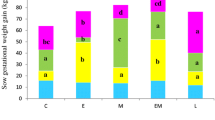

Weight gain in offspring was not different (Fig. 2) from birth to 12 weeks. However, offspring on the postnatal HE diet had more backfat, irrespective of their maternal dietary group (Fig. 3). Serum glucose was not affected by maternal treatment, but was higher (91 vs. 67 mg/dL) in offspring on the postweaning HE diet than those on the NE diet. Thus serum metabolite parameters may not be good predictors of long-term effects of maternal and postweaning diets at 12 weeks of age in pigs.

Body weight changes in offspring from gilts fed either a gestational normal energy (NE) or high energy (HE) diet and then fed either postweaning NE or HE diet to 12 weeks of age. Offspring were weighed on days 21, Body weights were measured at day 22, 29, 43, 57, 71 and 82 days postnatal. Body weights were not affected by treatment at any point. (NN, piglets from gilts fed gestational NE diet but fed postnatal NE diet; NE, piglets from gilts fed gestational NE diet but fed postnatal HE diet; HN, piglets from gilts fed gestational HE diet but fed postnatal NE diet; HE, piglets from gilts fed gestational HE diet but fed postnatal HE diet)

Backfat depth of offspring measured at day 84 (12 weeks postnatal). Backfat was measured at the 12th rib. a Postweaning diet effect. b separated treatment groups. Bars represent mean ± SEM. Superscript letters represent significant mean differences (P < 0.05). Offspring weaned to HE had higher backfat thickness (P < 0.05)

Adipose tissue gene expression

At 48 h after birth, genes such as SRC1 (steroid receptor coactivator 1), SFRP2 (secreted frizzled-related protein 2) and SET domain containing (lysine methyltransferase 8 (SETD8) were significantly higher (P < 0.05) in the adipose tissue of piglets from HE gilts, whereas there was a tendency (P < 0.06) for a higher HSD1 in the piglets from HE gilts as well (Table 3).

At weaning (Table 4), genes involved in differentiation, PPARγ (peroxisome proliferator activated receptor) and CEBPα (CCAAT Enhancer binding protein α), were higher in piglets (P < 0.05) from HE dams. In addition, FABP4 (fatty acid binding protein 4), involved in fatty acid transport, was induced under HE diet. Genes such as NCOR1 (nuclear receptor corepressor 1), SIRT1, GCCR (glucocorticoid receptor), FZD2 (frizzled class receptor 2), Wnt inhibitors secreted frizzled-related protein 4 and 5 (SFRP4 and SFRP5) and histone methyltransferases (SETDB1 and SETD8) were higher in HE piglets than NE. However, IL1β (interleukin 1β) expression was lower (P < 0.05) in HE piglets and there was a tendency (P < 0.06) for a lower expression of Wnt3a (Table 5).

At 12 weeks, there was no longer a maternal diet effect on most genes that were affected by maternal diet at weaning. Unlike at weaning, there was no effect of maternal diet or postweaning diet effect on PPARγ and CEBPα (Fig. 4). Expression of NCOR1 was lower (P < 0.05) in pigs on post weaning HE diet, but maternal diet effect was not significant. Expression of both SFRP5 and Wnt5a was higher (P < 0.05) in pigs on the postnatal HE diet than those on the NE diet (Fig. 5). In addition, there was a tendency (P < 0.09) for a lower ratio of Wnt5a/SFRP5. This ratio determines the amount of available Wnt5a and the ability of Wnt to regulate adipocyte differentiation. We also observed a tendency (P < 0.08) for a higher IGF-1 (insulin-like growth factor 1) expression in pigs on the post weaning HE diet than those on the NE diet. Expression of neurotrophic tyrosine kinase, receptor-related 2 (ROR2), another Wnt receptor, was higher in pigs on the post weaning HE diet. In addition, the expression of TNFα was lower (P < 0.05) in pigs on postnatal HE diet than those on the NE diet (Fig. 6) Other genes such as PREF1 (preadipocyte factor 1), CCDN1(cyclin D), FABP4 (fatty acid binding protein 4), IGFR1 (insulin-like growth factor receptor 1), GHR (growth hormone receptor), GCCR, HSD1 (hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase 1), SRC1, PGC1α (PPAR gamma coactivator 1), SIRT1, SERPINE (serpin peptidase inhibitor, clade E, nexin, plasminogen activator type 1), Wnt5a (wingless-type MMTV integration site family, member 5a), Wnt10b, FZD1, FZD2, FZD7, SFRP2, SFRP4, SETDB1 and SETD8 were neither affected by maternal nor post weaning diet (data not shown). Thus, compared to week 3, maternal diet had limited effect on offspring adipose tissue gene expression pattern.

Gene expression analysis of offspring subcutaneous backfat obtained at postnatal day 84. Expression of PPARγ (a, b and c), CEBPα (d, e and f) and NCOR1 (g, h and i) was measured by RT-PCR and expressed relative to 18 s. Bars represent mean ± SEM. Superscript letters represent significant mean differences (P < 0.05)

Gene expression analysis of offspring subcutaneous backfat obtained at postnatal day 84. Expression of SFRP5 (a, b and c) and Wnt5a (d, e and f) were measured by RT-PCR and expressed relative to 18 s. Their ratio (WNT5a/SFRP5) (g, h and i) was also determined. Bars represent mean ± SEM. Superscript letters represent significant mean differences (P < 0.05)

Gene expression analysis of offspring subcutaneous backfat obtained at postnatal day 84. Expression of IGF-1 (a, b and c), ROR2 (d, e and f) and TNFα (g, h and i) were measured by RT-PCR and expressed relative to 18 s. Bars represent mean ± SEM. Superscript letters represent significant mean differences (P < 0.05)

Discussion

Excessive weight gain during gestation remains a major problem in many women of child-bearing age in the US and across the globe [17]. In this study we have evaluated the effect of maternal weight gain during gestation on adipose tissue programming in the offspring. Because predisposition to obesity development is affected by both maternal diet during gestation and offspring postnatal diet, we also determined the effects of postweaning nutrition on adipose tissue gene expression pattern at 12 weeks of age as a way of determining programming for future adipose tissue expansion.

Recent estimates of pregnancy weight gain in the US project that less than half of pregnancies in the U.S. meet the IOM guidelines with a clear majority of the pregnancies gaining more than the recommended amount of weight based on pre-pregnancy BMI [18]. Recent evidence also suggests GWG is associated with increased offspring birth weight independent of genetics [19]. Fat deposition is a major component of maternal weight gain [20]. During gestation there is accumulation of protein, fat, water and minerals into the products of conception (fetus, placenta and amniotic fluid) as well as the maternal uterus, mammary gland, blood and adipose tissue [21]. Fat accretion is targeted primarily to the subcutaneous adipose tissue depots in the hips, back and upper thighs [22, 23] in a pattern unique to pregnancy. Therefore, results of the higher backfat accumulation in the gilts on the gestational HE diet indicate that the increased calorie consumption resulted in higher maternal adiposity. However, there was no effect of maternal diet on offspring birth weight, weaning weight or weight at 12 weeks. This is in contrast to studies where maternal calorie consumption and obesity have been shown to lead to increased offspring weight [1, 3, 4]. However, this may indicate the limitation of the experimental diets used in this study to affect offspring weights in the immediate postnatal period. The increased expression of genes such as SRC1, SFRP2, SETD8 and the trend for a higher HSD1 at 48 h after birth in piglets from mothers on the HE diet indicates unique adipose tissue effects of maternal diet. The induction of SETD8 is consistent with maternal diet causing epigenetic changes in the offspring in a way that can affect offspring adiposity. Both SETD8 and PPARγ co-regulate each other in a positive feedback loop during adipogenesis, and the suppression of SETD8 suppresses adipogenesis [23]. Thus, as established through surgically-induced placental insufficiency [23, 24] and diet-induced maternal obesity [25], consumption of excess energy during gestation in pigs can also result in the modification of the histone code. Additionally, SRC1 increases the transcriptional activity of PPARγ [26]. Soluble frizzle related receptors (SFRP) are negative regulators of wnt signaling [27]. Their binding to wnt prevents the inhibitory effects of wnt on adipogenesis [28] and SFRP 1–4 are adipokines that are upregulated in human models of obesity [29]. Thus upregulation of SFRP2 in the adipose tissue of piglets from mothers on the HE diet is consistent programming for increased adipogenic potential in those offspring through the inhibition of wnt signaling.

Clinical implication

Developmental plasticity extends past gestation to include neonatal life [30, 31]. The data obtained at 3 weeks fall within this perinatal programming window. Indeed, increased expression of multiple genes at 3 weeks suggest a significant maternal effect. Higher expression of genes involved in differentiation (PPARγ, CEBPα and FABP4, fatty acid binding protein 4) suggest increased differentiation potential in HE offspring at weaning, because these genes are known to directly increase adipocyte differentiation and are induced in several models of obesity [32]. The lower expression of NCOR1, a transcriptional suppressor of PPARγ, and the upregulation of SETD8 (a transcriptional activator of PPARγ) and wnt inhibitors (SFRP4 and SFRP5), also provide evidence that offspring from the HE gilts have increased adipogenic potential at 3 weeks. The induction of GCCR in offspring from HE gilts is consistent with the established effect of glucocorticoids in increasing adipogenesis [33]. However, higher expression of SIRT1, SETDB1 and FZD2, negative regulators of PPARγ and adipogenesis [34–36] also suggests that HE diet may induce negative feedback mechanisms to limit adipose tissue expansion in the offspring. The lower expression of IL1β in HE piglets indicates lower inflammation status and suggests a healthy adipose tissue expansion in the HE offspring. This is not surprising as the gene expression profile suggests a higher PPARγ activity at 3 weeks, and increased PPARγ activity is associated with increased adipose tissue expansion but reduced inflammation [37]. This phenomenon is known as healthy adipose tissue expansion due to the lack of inflammation [38]. This is in contrast to pathological adipose tissue expansion that may be accompanied by increased inflammation [39]. The increased expression of adipogenic genes in the adipose tissue of HE gilts may be tied to the increased lipid (and presumably energy) content of the milk from HE gilts. As previously established, offspring exposed to a calorie-rich suckling period exhibit increased adiposity, hyperleptinemia and hypertension during adulthood [40]. In addition, pups reared in small litters, which presumably have access to greater food supply, exhibit adipocyte hyperplasia and obesity by the end of a 21-day suckling period [41]. Artificially reared pups on a high carbohydrate diet during the suckling period also experience increased adiposity [9]. Thus, increased maternal calorie consumption during gestation may predispose offspring to early increase in adipose tissue expansion which may lead to future obesity.

However, at 12 weeks of age, most of the programming effects seen in the adipose tissue at 3 weeks had completely disappeared, and the effect of the postweaning HE diet was predominant. The higher expression of NCOR1 and SFRP5 in pigs on postweaning HE diet is consistent with increased adipogenic potential from the postweaning HE diet. However, negative regulators of adipogenesis, Wnt5a and ROR2 (receptor tyrosine kinase-like orphan receptor 2), were also induced, potentially to limit adipose accretion from the HE diet. Nevertheless, the tendency (P < 0.09) for a lower ratio of Wnt5a/SFRP5 and higher IGF-1 support an increased adipogenic potential on the post weaning HE diet. A healthy adipose expansion may be occurring as a result of the HE diet as expression of TNFα (tumor necrosis factor-α) was lower on the HE diet than the NE. This is reflected in the higher backfat in the offspring on the postweaning HE diet. Thus, although effects of high maternal calorie consumption is reflected in increased capacity for adipose tissue expansion in early life in the offspring, these effects may not be permanent and postweaning diets may alter the effects of maternal gestational diet on the risk for obesity development.

Limitations

Because the pigs were killed at 12 weeks of age, we were not able to determine the final effect of both gestational and postweaning HE diets on adiposity in adult pigs. However, our data support a significant programming of adiposity by maternal and immediate postnatal dietary energy intake. The effects of these initial periods on the final adiposity in the mature offspring will need longer term studies than was done in the current study.

Conclusions

Effects of the higher energy content in the maternal and postweaning diets are observable in the adipose tissue in the offspring, potentially setting the stage for greater adiposity in adulthood. Thus, the pig represents an excellent animal model for investigating the effects of both maternal and offspring dietary energy consumption on offspring capacity for adipose tissue deposition. Therefore, unlike human infants, the pig model can be used for determining adipose tissue programming across all ages in the offspring.

Abbreviations

BMI, Body Mass Index; CEBPα, CCAAT Enhancer Binding Protein α; FZD2, Frizzled Class Receptor 2; GCCR, Glucocorticoid Receptor; HE, High Energy; IL1β, Interleukin 1β; IOM, Health Institute of Medicine; NCOR1, Nuclear Receptor Corepressor 1; NE, Normal Energy; NEFA, Non-Esterified Fatty Acid; Pgc1a, Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor Gamma Coactivator-1a; PPARγ, Peroxisome Proliferator Activated Receptor Gamma; SETD8, SET Domain containing (lysine methyltransferase 8; SFRP2, Secreted Frizzled-Related Protein 2; SIRT1, Sirt1, NAD-dependent Deacetylase Sirtuin-1; SRC1, Steroid Receptor Coactivator-1

References

Butte NF, Ellis KJ, Wong WW, Hopkinson JM, Smith EO. Composition of gestational weight gain impacts maternal fat retention and infant birth weight. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189(5):1423–32.

Viswanathan M, Siega-Riz AM, Moos MK, Deierlein A, Mumford S, Knaack J, Thieda P, Lux LJ, Lohr KN. Outcomes of maternal weight gain. Evid Rep Technol Assess (Full Rep). 2008;168:1–223.

Crane MG, White J, Murphy P, Burrage LDH. The effect of gestational weight gain by body mass index on maternal and neonatal outcomes. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2009;31(1):28–35.

Oken E, Taveras EM, Kleinman KP, Rich-Edwards JW, Gillman MW. Gestational weight gain and child adiposity at age 3 years. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;196(4):322. e321-328.

Wrotniak BH, Shults J, Butts S, Stettler N. Gestational weight gain and risk of overweight in the offspring at age 7 y in a multicenter, multiethnic cohort study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;87(6):1818–24.

Crozier SR, Inskip HM, Godfrey KM, Cooper C, Harvey NC, Cole ZA, Robinson SM. Weight gain in pregnancy and childhood body composition: findings from the Southampton Women’s Survey. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;91(6):1745–51.

Fraser A, Tilling K, Macdonald-Wallis C, Sattar N, Brion MJ, Benfield L, Ness A, Deanfield J, Hingorani A, Nelson SM, Smith GD, Lawlor DA. Association of maternal weight gain in pregnancy with offspring obesity and metabolic and vascular traits in childhood. Circulation. 2010;121(23):2557–64.

Van Lieshout RJ, Taylor VH, Boyle MH. Pre-pregnancy and pregnancy obesity and neurodevelopmental outcomes in offspring: a systematic review. Obes Rev. 2011;12(5):e548–559.

Srinivasan M, Mitrani P, Sadhanandan G, Dodds C, Shbeir-ElDika S, Thamotharan S, Ghanim H, Dandona P, Devaskar SU, Patel MS. A high-carbohydrate diet in the immediate postnatal life of rats induces adaptations predisposing to adult-onset obesity. J Endocrinol. 2008;197(3):565–74.

Zambrano E, Martinez-Samayoa PM, Rodriguez-Gonzalez GL, Nathanielsz PW. Dietary intervention prior to pregnancy reverses metabolic programming in male offspring of obese rats. J Physiol. 2010;588(Pt 10):1791–9.

Armitage JA, Khan IY, Taylor PD, Nathanielsz PW, Poston L. Developmental programming of the metabolic syndrome by maternal nutritional imbalance: how strong is the evidence from experimental models in mammals? J Physiol. 2004;561(Pt 2):355–77.

Gallou-Kabani C, Vigé A, Gross MS, Boileau C, Rabes JP, Fruchart-Najib J, Jais JP, Junien C. Resistance to high-fat diet in the female progeny of obese mice fed a control diet during the periconceptual, gestation, and lactation periods. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2007;292(4):E1095–1100.

Khan IY, Dekou V, Douglas G, Jensen R, Hanson MA, Poston L, Taylor PD. A high-fat diet during rat pregnancy or suckling induces cardiovascular dysfunction in adult offspring. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2005;288(1):R127–133.

Kirk SL, Samuelsson AM, Argenton M, Dhonye H, Kalamatianos T, Poston L, Taylor PD, Coen CW. Maternal obesity induced by diet in rats permanently influences central processes regulating food intake in offspring. PLoS One. 2009;4(6):e5870.

Arentson-Lantz EJ, Buhman KK, Ajuwon K, Donkin SS. Excess pregnancy weight gain leads to early indications of metabolic syndrome in a swine model of fetal programming. Nutr Res. 2014;34(3):241–9.

Patience JF, Shand P, Pietrasik Z, Merrill J, Vessie G, Ross KA, Beaulieu AD. The effect of ractopamine supplementation at 5 ppm of swine finishing diets on growth performance, carcass composition and ultimate pork quality. Can J Anim Sci. 2009;89:53–66.

Johnson JL, Farr SL, Dietz PM, Sharma AJ, Barfield WD, Robbins CL. Trends in gestational weight gain: the pregnancy risk assessment monitoring system, 2000–2009. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;212(6):806. e1-8.

Ctripw G, Iomnr C. In: KM Rasmussen AY, editor. Weight gain during pregnancy: reexamining the guidelines. US: National Academies Press; 2009.

Ludwig DS, Currie J. The association between pregnancy weight gain and birthweight: a within-family comparison. Lancet. 2010;376(9745):984–90.

Stirrat GM, Jacobs HS, Klopper A: Clinical physiology in obstetrics; Hytten F, Chamberlain G, editors: Blackwell Scientific Publications, Oxford, 1980.

Sohlström A, Forsum E. Changes in adipose tissue volume and distribution during reproduction in Swedish women as assessed by magnetic resonance imaging. The Am J Clin Nutr. 1995;61(2):287–95.

Taggart NR, Holliday RM, Billewicz WZ, Hytten FE, Thomson AM. Changes in skinfolds during pregnancy. Br J Nutr. 1967;21(2):439–51.

Wakabayashi K, Okamura M, Tsutsumi S, Nishikawa NS, Tanaka T, Sakakibara I, Kitakami J, Ihara S, Hashimoto Y, Hamakubo T, Kodama T, Aburatani H, Sakai J. The peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma/retinoid X receptor alpha heterodimer targets the histone modification enzyme PR-Set7/Setd8 gene and regulates adipogenesis through a positive feedback loop. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29(13):3544–55.

Fu Q, McKnight RA, Yu X, Wang L, Callaway CW, Lane RH. Uteroplacental insufficiency induces site-specific changes in histone H3 covalent modifications and affects DNA-histone H3 positioning in day 0 IUGR rat liver. Physiol Genomics. 2004;20(1):108–16.

Aagaard-Tillery KM, Grove K, Bishop J, Ke X, Fu Q, McKnight R, Lane RH. Developmental origins of disease and determinants of chromatin structure: maternal diet modifies the primate fetal epigenome. J Mol Endocrinol. 2008;41(2):91–102.

Lizcano F, Vargas D. Diverse coactivator recruitment through differential PPARgamma nuclear receptor agonism. Genet Mol Biol. 2013;36(1):134–9.

Surana R, Sikka S, Cai W, Shin EM, Warrier SR, Tan HJ, Arfuso F, Fox SA, Dharmarajan AM, Kumar AP. Secreted frizzled related proteins: Implications in cancers. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1845(1):53–65.

Park JR, Jung JW, Lee YS, Kang KS. The roles of Wnt antagonists Dkk1 and sFRP4 during adipogenesis of human adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Cell Prolif. 2008;41(6):859–74.

Ehrlund A, Mejhert N, Lorente-Cebrián S, Aström G, Dahlman I, Laurencikiene J, Rydén M. Characterization of the Wnt inhibitors secreted frizzled-related proteins (SFRPs) in human adipose tissue. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98(3):E503–508.

Hanson MA, Gluckman PD. Developmental origins of health and disease: moving from biological concepts to interventions and policy. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2011;115 Suppl 1:S3–5.

Taylor PD, Poston L. Developmental programming of obesity in mammals. Exp Physiol. 2007;92(2):287–98.

Zuo Y, Qiang L, Farmer SR. Activation of CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein (C/EBP) alpha expression by C/EBP beta during adipogenesis requires a peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma-associated repression of HDAC1 at the C/ebp alpha gene promoter. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(12):7960–7.

Ringold GM, Chapman AB, Knight DM. Glucocorticoid control of developmentally regulated adipose genes. J Steroid Biochem. 1986;24(1):69–75.

Picard F, Kurtev M, Chung N, Topark-Ngarm A, Senawong T, Machado De Oliveira R, Leid M, McBurney MW, Guarente L. Sirt1 promotes fat mobilization in white adipocytes by repressing PPAR-gamma. Nature. 2004;429(6993):771–6.

Takada I, Kouzmenko AP, Kato S. Molecular switching of osteoblastogenesis versus adipogenesis: implications for targeted therapies. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2009;13(5):593–603.

Ahn J, Lee H, Kim S, Ha T. Curcumin-induced suppression of adipogenic differentiation is accompanied by activation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2010;298(6):C1510–1516.

Tsuchida A, Yamauchi T, Takekawa S, Hada Y, Ito Y, Maki T, Kadowaki T. Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor (PPAR) Activation Increases Adiponectin Receptors and Reduces Obesity-Related Inflammation in Adipose Tissue: Comparison of Activation of PPAR, PPAR, and Their Combination. Diabetes. 2005;54(12):3358–70.

Petrovic N, Walden TB, Shabalina IG, Timmons JA, Cannon B, Nedergaard J. Chronic peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARgamma) activation of epididymally derived white adipocyte cultures reveals a population of thermogenically competent, UCP1-containing adipocytes molecularly distinct from classic brown adipocytes. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(10):7153–64.

Lumeng CN, Bodzin JL, Saltiel AR. Obesity induces a phenotypic switch in adipose tissue macrophage polarization. J Clin Invest. 2007;117(1):175–84.

Plagemann A. Perinatal programming and functional teratogenesis: impact on body weight regulation and obesity. Physiol Behav. 2005;86(5):661–8.

Schmidt I, Fritz A, Schölch C, Schneider D, Simon E, Plagemann A. The effect of leptin treatment on the development of obesity in overfed suckling Wistar rats. International journal of obesity and related metabolic disorders : Journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity. 2001;25(8):1168–74.

Acknowledgements

Authors acknowldge assistance from Meliza Ward, Hui Yan, Jim Emilson, Darryl Ragland and Hang Lu for animal health and husbandry support.

Funding

The authors acknowledge funding support from the Showalter Foundation.

Availability of data and materials

All supporting data is contained within the manuscript.

Authors’ contributions

KMA and SSD designed the study, EAL KMA and SSD assisted in collecting all swine data, analyzed and interpreted data, and wrote the manuscript. All authors approved the final version.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent to publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was carried out in strict accordance with the recommendations in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the National Institutes of Health. The Purdue Animal Care and Use Committee (PACUC) approved all procedures on care and use of pigs described in this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Ajuwon, K.M., Arentson-Lantz, E.J. & Donkin, S.S. Excessive gestational calorie intake in sows regulates early postnatal adipose tissue development in the offspring. BMC Nutr 2, 29 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40795-016-0069-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40795-016-0069-3