Abstract

Background

Anemia is pervasive among children under the age of two years in Bangladesh. This study aimed to assess the effect of daily supplementation of multiple micronutrient powder (MNP) for 2 months and 4 months primarily on hemoglobin status of children aged 6–23 months living in a slum of Dhaka, Bangladesh.

Methods

It was a community-based observational study where a total of 402 children and 578 children were enrolled for 2 months and 4 months MNP supplementation respectively. Venous blood was collected at enrollment and 5 months later. Hemoglobin level was measured and morbidity episodes recorded from twice weekly home visits.

Results

At enrollment, hemoglobin levels were 10.57 ± 1.28 g/dl and 10.78 ± 1.35 g/dl across 2 months and 4 months MNP supplementation groups respectively, compared to 10.65 ± 1.36 g/dl and 11.14 ± 1.11 g/dl at the end-line after MNP supplementation. Plasma hemoglobin increased only after 4 months supplementation in difference-in-difference analysis and this was significantly more in younger children after adjusting the confounding variables (p = 0.03). Prevalence of anemia had improved for both at 2 months (p = 0.015) and 4 months (p = 0.004) of MNP supplementation. Incidence rate ratios (IRR) for diarrhea, cough and fever were comparable across the groups during the supplementation periods and IRR for acute lower respiratory tract infection was significantly lower in 4 months supplementation group with a IRR of 0.30 (95 % CI; 0.22, 0.42).

Conclusion

Four months MNP supplementation was relatively more effective in improving hemoglobin level in children 6–24 months.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Globally 270 million children under the age of 5 years are affected by anemia with highest prevalence in developing countries [1]. Anemia is prevalent among all age groups in Bangladesh especially among 6–23 month old children (62.5 %–78.7 %) [2]. According to World Health Organization (WHO), anemia prevalence of 40 % or more in any population is considered as a severe public health problem [3]. The alarmingly high prevalence of anemia among children, coupled with its associated adverse health, development and economic consequences highlights the need for intensified actions to address this ongoing public health problem. Iron deficiency, as defined by specific biochemical tests, is the most common cause of anemia in most parts of the world [4].

In developing countries, only a small fraction of the recommended daily iron requirement comes from complementary foods, and most of the consumed iron is of plant origin which absorbs less in the body than animal source iron, which together with the lack of any additional supplementation causes a large number of children to suffer from iron deficiency [5–8]. However, in recent years, home fortification of complementary foods with multiple micronutrient powders (MNP) has been proven to be the most effective and cost-efficient strategy to reduce iron deficiency and hence combat anemia in comparison to other interventions [9–12]. Two systematic reviews have concluded that MNP is as effective as iron drops in improving hemoglobin status and reduction of anemia. MNP supplementation also had better acceptance than iron drops among children and exhibits fewer side effects [9, 10]. The latest Cochrane review on the effects and safety of home fortification of foods with MNP in children under 2 implies that the use of MNP in home fortification of food resulted in reduction of anemia by 31 % [13]. Regarding the frequency and duration of MNP supplementation, the home fortification technical advisory group of WHO recommended that 60–180 sachets of MNP sachets should be made available to target groups (children 6–23 months) over a period of 6 months [14]. However, data on optimum duration for MNP supplementation is still uncertain for countries like Bangladesh, particularly in slum settings.

This current analysis took the opportunity of Malnutrition-Enteric disease (MAL-ED) study [15], where children were provided with daily MNP supplementation in a slum setting of Dhaka city [16]. The primary aim of this study was to evaluate the relative efficacy of MNP served for two and four months period on improving plasma hemoglobin level among 6–24 months old children. This study also investigated the morbidity episodes during the MNP supplementation period and also compared the morbidity episodes with a group of children of same age from the same community without MNP supplementation.

Methods

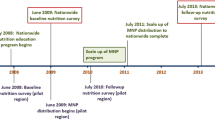

This observational study was performed within the ongoing study of Etiology, Risk Factors, and Interactions of Enteric Infections and Malnutrition and the Consequences for Child Health (MAL-ED). The MAL-ED study is a multi-country study focused on gaining a better understanding of the risk factors contributing to malnutrition and enteric diseases and their associated health consequences in children of developing countries [15]. In Bangladesh, the study is being conducted among residents of an under-privileged urban community in Bauniabad slum in Mirpur, Dhaka [16]. As per the icddr,b institutional review board approved protocol of MAL-ED study in Dhaka, MNP was provided to all study children for 2 months considering the high prevalence of childhood anemia in Bangladesh. However, interim results showed that the anemia reduction was less than it was previously anticipated. Considering the success stories of longer duration MNP supplementation in Ghana and Cambodian MNP trials [17, 18], we decided to continue to provide MNP supplementation for an additional 2 months for the rest of the children. MNP was provided in sachets, with daily allowance of one sachet per child, 6 days a week for either 2 months or 4 months to all participating children. The first child was enrolled on November 15, 2009 and the last child on December 18, 2012.

Each sachet of MNP contained: 12.5 mg iron, 5 mg zinc, 300 μg vitamin A, 150 μg folic acid, and 50 mg of vitamin C. MNP sachets were distributed among the children when they attended 6 days a week one of the four feeding outposts established for the study within the slum. The caregivers (mother, grandmother or an older sibling) were asked to feed the children MNP by sprinkling the sachet contents over their first one or two servings of offered food, during the feeding sessions at the outposts. The research staff directly observed and recorded consumption of MNP by the children.

Biological sample collection and laboratory testing

Five ml of venous blood was collected from enrolled children at enrollment and 5 months. Hemoglobin (Hb) level was tested. Hb was measured by direct cyanmethemoglobin method [19] at the Nutritional Biochemistry Laboratory of icddr,b.

Collection of morbidity data

Morbidity episodes of the participants during the study period were collected through active surveillance where health workers recorded all morbidity episodes by visiting each home twice a week for 5 months from enrollment.

Study participants included in analysis

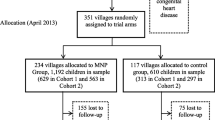

A total of 1,123 children were eligible for the study and 980 children were enrolled. During the course of the study, 172 (17.6 %) children were lost to follow up and 808 children completed the study. Among the children who were lost to follow-up, 98 moved out from the study site, 50 decided to withdraw from the study as their parents did not want them to provide blood and 21 left the study without any known reasons. Three children died during the course of the study and deaths of three participants were not linked with any activities of the study. One child died from complication of Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML), and other two children were suffering from severe acute malnutrition (SAM). The SAM children died during their visit to their grandfather’s houses at rural districts where they had developed bronco-pneumonia and acute watery diarrhea respectively and were treated by unqualified medical practitioners. Due to hemolysis and clotting (162 in baseline and 131 in endline), hemoglobin results were available for 818 children at baseline and 511 children at endline. The study profile is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Statistical analysis

All data were entered into the computer after carefully cross-checked and used double data entry method. Statistical analyses were done using STATA (Version 13.1; StataCorp, College Station, Texas, USA). Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05. The distributions of data were checked for normality by using histogram, QQ plot and kurtosis & skewness. We compared baseline characteristics between MNP groups using Student’s t tests, Pearson chi-square tests and Mann–Whitney U test. Both parametric and nonparametric approaches were used for analyses and reported as medians and interquartile ranges, or mean and standard division.

To explore the effect of 4 months MNP supplementation (TE) on hemoglobin level, we carried out the following analysis:

Calculation of crude % enhancement in hemoglobin level

The 4 months MNP supplementation effect was calculated by the following formula:

-

TE: [(B − A) − (D − C)]

Where, A = baseline mean value for the 4 months MNP supplementation group; B = endline mean value for the 4 months MNP supplementation group; C = baseline mean value for the 2 months MNP supplementation group; D = endline mean value for the 2 months MNP supplementation group.

The percent enhancement by 4 months MNP supplementation calculated as:

-

[(TE/A) * 100]

To assess the effect of the 4 months MNP supplementation we used difference-in-difference technique is as follows:

-

Yit = β0 + β1 Time + β2 Group + δ (Time × Group) + β3 X + ε

-

Where,

-

Yit = Outcome variable of interest for individual i at time t

-

Time = (1) if endline and (0) if baseline

-

Group = (1) if 4 months MNP supplementation and (0) if 2 months MNP supplementation

-

δ = The effect of the 4 months MNP supplementation

-

X = Other covariates

-

ε = Error term

Anemia was defined as hemoglobin less than 11 g/dl. To compare morbidity episodes between the groups we used Incidence rate ratio (IRR) with generalized linear models with a Poisson distribution. We also compared these morbidity episodes with the similar data from MAL-ED birth cohort children of the same community who were followed since birth and not provided with MNP supplementation. This comparison group was categorized in different age groups to match with 2 months and 4 months supplementation groups and IRRs were calculated after adjusting all possible confounders and compared over a period of 4 months.

Ethics, consent and permissions

The research protocol was approved by the Research Review Committee and the Ethical Review Committee of International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research, Bangladesh (protocol number: PR-2008–020). Eligible children were enrolled in the study after collecting informed written consent from their parent/guardian.

Results

Our analysis showed two months supplementation group had more numbers of older, underweight and wasted children in the baseline (Table 1). Initiation of breast feeding within 1 h of birth was higher among children with 4 months MNP supplementation. Thirty percent of the children were introduced to soft and semisolid food before 6 months of age. More children in 2 months MNP group received vitamin A supplementation through the government program in comparison to 4 months MNP group. Similar baseline findings were also observed among the children who’s data were not analyzed due to unavailable Hb data. Adherence to MNP supplementation between 2 months and 4 months MNP groups was similar, where the percentages of good adherence were 85.16 % and 86.90 % for 2 months and 4 months groups, respectively. Here good adherence means consumption of 75 % of MNP sachets per child at the end of intervention period; 45 sachets for 2 months supplementation and 90 sachets for 4 months supplementation. At the baseline, hemoglobin levels were 10.57 ± 1.28 g/dl and 10.78 ± 1.35 g/dl for 2 months and 4 months supplementation groups, respectively. The difference was statistically significant (p < 0.05). At the end of intervention period, hemoglobin levels were 10.65 ± 1.36 g/dl for 2 months supplementation group and 11.14 ± 1.11 g/dl for 4 months supplementation group. The change of improvement of hemoglobin level was significant (p < 0.05) only after 4 months supplementation and there was 2.5% point enhancement of hemoglobin level after 4 months MNP supplementation which was observed in difference-in-difference analysis. In the difference-in-difference analysis, we have adjusted for all the confounding variables significant at baseline in the regression model which include hemoglobin, gender, stunting, food security and vitamin A supplementation status between two age groups: 6–11 months and 12–23 months (Table 2). Adjusted data showed that there was no difference between the baseline Hb levels between 2 months and 4 months MNP supplementation groups for both age groups and 6–11 months age group has a significant improvement of 4 months supplementation (p < 0.05) (Table 2).

In terms of change in anemia status, statistically significant reduction of 9 % in the 2 months MNP group and 12 % in the 4 months MNP group were noted, suggesting that the intervention was effective in decreasing prevalence of anemia in both the groups (Fig. 2). However, no significant difference was observed in difference-in-difference analysis between the supplementation groups (p < 0.05).

Finally, we calculated morbidity episodes from the surveillance data for each day up to 4 months, we observed no difference in incidence rate ratios (IRR) for diarrhea, cough and fever between 2 and 4 months MNP supplementation groups. Moreover, IRR for acute lower respiratory tract infection (ALRI) was significantly low in 4 month MNP supplementation group with IRR (95 % CI) of 0.30 (0.22, 0.42). In comparison to MAL-ED children without MNP supplementation, after adjusting gender, nutritional status and food security status, for 6–11 months age group, there were higher incidences of diarrhoea, and ALRI in 2 months MNP supplementation group and higher incidences of diarrhoea and cough in 4 months supplementation group. However, for the children 12–17 months, apart from higher numbers of new episodes of ALRI in 2 months supplementation group, there were no differences in IRR of morbidity episodes between MAL-ED cohort children and both the supplementation groups. Moreover, for 18–24 months age, children with 4 months MNP supplementation had significant fewer episodes of fever and cough compared to MAL-ED cohort children (Fig. 3 and Table 3).

Discussion

This study examined the effect of daily dosage of 2 months and 4 months of multiple micronutrient powder supplementations on hemoglobin status of children 6–23 months in a slum of Dhaka. The results of this study had clearly shown the relative improvement of hemoglobin level in the 4 months group but not in the 2 months group, but significant reduction in prevalence of anemia in both MNP supplementation groups.

There are limited numbers of published studies that assessed the effect of MNP on anemia beyond 2 months of daily supplementation [13]. The reduction in the prevalence of anemia in this study is in concordance with a recently completed study which compared 2 months of daily MNP supplementation with 3 months and 4 months of flexible MNP supplementation in children under the age of 24 months from Bangladesh [20] and observed significant reduction in the prevalence of anemia across all three intervention groups when compared to baseline prevalence. In a cluster randomized study at rural Nepal observed a significant improvement of hemoglobin status after providing MNP to children 6–9 months old over a period of 11 months in flexible doses [21]. Moreover, in a community-based randomized trial in Ghana, significant effect on reduction of anemia prevalence was observed from daily dosage of MNP for 6 months among children from 6 to 12 months of age [17]. The anemia prevalence decreased from 30 % at 6 months to 18 % at 12 months which is consistent with the current study. In another study, Giovannini et al. assessed the effectiveness of daily MNP supplementation on anemia and iron deficiency status in Cambodian infants over a period of one year [17]. At the end of the study period, MNP was found to be comparable to iron drop in preventing and treating anemia as well as stabilizing plasma ferritin level. The Cochrane review also found significant reduction of anemia after both 2 months and more than 2 months of MNP supplementation and the risk reduction was higher after longer duration of MNP supplementation (44 % vs 31 %) [14]. In multivariate analysis, when we stratified the children in two age groups as 6–11 months and 12–23 months; after adjustment of the confounders, we observed that 4 months supplementation worked better than 2 months in younger children. There has been paucity of evidence to support this finding [22]. In Haiti, Menon et al. 2007 observed the similar phenomena. They provided MNP supplementation to 6–24 months age children for 2 months and observed that older children did not benefit from MNP to the same degree as younger children did [22]. It could be due to the fact that older children had low iron requirement and more consumption of phytate containing cereals that reduced iron absorption [23].

Finally, it should be noted that the relationship between increased infection and iron supplementation is ambiguous and debatable [24]. During infection, micro-organisms require iron for their proliferation [25]. On the other hand, iron is essential for host immunity which combats infection [26]. A systematic review of 28 randomized controlled studies showed no obvious harmful effect on the overall incidence of infectious illnesses in children after iron supplementation [27]. In this study we observed significantly fewer episodes of infectious morbidity in children with 4 months MNP supplementation when compared to 2 months MNP supplementation. This finding is in contrast to a study conducted in Zanzibar [28] and Pakistan [29] where they found significantly increased number of morbidity episodes after MNP consumption. However, it should be noted that the Zanzibar study did not find any significant adverse events associated with MNP consumption in the 6–11 months group and in the Pakistan trial, incidence of febrile illness or admission to hospital for diarrhea and respiratory problems did not differ between the MNP and control groups. When we compared the IRR of morbidity with the comparison group (MAL-ED cohort), the result was mixed and inconclusive. For younger children (6-11months), comparison group was better and 4 months supplementation group was middle in terms of fewer numbers of episodes. Morbidity episodes were similar for 12–17 months children across all three comparators. And for older children (18–24 months), 4 months MNP group was better, comparison MAL-ED cohort was middle and 2 months MNP group was worse. Relatively fewer episodes of morbidity among the comparison children at younger age could be explained by the fact that the MAL-ED children were recruited as healthy newborns, so better immunity, hence fewer chances of infectious morbidities [30]. Moreover, continuous interaction with the mothers and the research staff from the rigorous data collection in MAL-ED cohort study might responsible for “Hawthrone effect” resulted in reduced morbidity episodes [16, 21].

There are several limitations in this study. The study was not a randomized controlled trial because the original study was not designed to assess the efficacy of MNP supplementation at different duration. Moreover, the duration between the baseline and endline blood collection for the supplementation groups were also different.

Conclusion

Prevalence of anemia improved after both 2 months and 4 months MNP supplementation. However, 4 months MNP supplementation was more effective in improving hemoglobin status. Additionally, no additional infectious morbidities were observed after 4 months supplementation. In areas with high burden of anemia, MNP supplementation for a period for 4 months would most likely be beneficial to combat the existing high prevalence of childhood anemia.

Availability of data

Due to restriction in icddr,b’s data access policy in regard to participants identifying information, data are available upon request from the Research & Clinical Administration and Strategy (RCAS) of icddr,b (http://www.icddrb.org/component/content/article/10003-data-policies/1893-data-policies) for researchers who meet the criteria for access to confidential data.

Abbreviations

- ALRI:

-

acute lower respiratory tract infection

- CI:

-

confidence interval

- Hb:

-

hemoglobin

- icddr,b:

-

International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research, Bangladesh

- IRR:

-

incidence rate ratios

- MAL-ED:

-

study of Etiology, Risk Factors, and Interactions of Enteric Infections and Malnutrition and the Consequences for Child Health

- MNP:

-

multiple micronutrient powder

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Stevens GA, Finucane MM, De-Regil LM, Paciorek CJ, Flaxman SR, Branca F, Peña-Rosas JP, Bhutta ZA, Ezzati M, Nutrition Impact Model Study Group (Anaemia). Global, regional, and national trends in haemoglobin concentration and prevalence of total and severe anaemia in children and pregnant and non-pregnant women for 1995-2011: a systematic analysis of population-representative data. Lancet Glob Health. 2013;1(1):e16–25.

NIPORT/Mitra and Associates/Macro International. Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey 2011. Dhaka: National Institute of Population Research and Training, Mitra and Associates, Macro International; 2012. p. 177. http://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR265/FR265.pdf.

Benoist BD, McLean E, Egil I, Cogswell M. Worldwide prevalence of anaemia 1993-2005: WHO global database on anaemia. World Health Organization 2008. http://www.who.int/nutrition/publications/micronutrients/anaemia_iron_deficiency/9789241596657/en/. Accessed 24 Jun 2014.

World Health Organization (2001) Iron deficiency anaemia: assessment, prevention, and control. A guide for programme managers. WHO/NHD/01.3. http://www.who.int/nutrition/publications/en/ida_assessment_prevention_control.pdf. (Accessed May 2015).

Hotz C, Gibson R. Complementary feeding practices and dietary intakes from complementary foods amongst weanlings in rural Malawi. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2001;55(10):841–9.

Hunt JR. Bioavailability of iron, zinc, and other trace minerals from vegetarian diets. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;78(suppl):633S–9S.

Arsenault JE, Yakes EA, Islam MM, Hossain MB, Ahmed T, Hotz C, Lewis B, Rahman AS, Jamil KM, Brown KH. Very low adequacy of micronutrient intakes by young children and women in rural Bangladesh is primarily explained by low food intake and limited diversity. J Nutr. 2013;143(2):197–203.

Kimmons JE, Dewey KG, Haque E, Chakraborty J, Osendarp SJ, Brown KH. Low nutrient intakes among infants in rural Bangladesh are attributable to low intake and micronutrient density of complementary foods. J Nutr. 2005;135(3):444–51.

Ahmed T, Abdullah K, Ahmed AM, Mahfuz M, Cravioto A, Sack D. Efficacy and effectiveness of micronutrient powder on childhood anemia and growth. Nutrition Intervention for Maternal and Child Health and Survival. Karachi: Oxford University Press; 2010.

Dewey KG, Chaparro CM. Session 4: Mineral metabolism and body composition Iron status of breast-fed infants. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society. 2007;66(3):412–22.

Dewey KG, Yang Z, Boy E. Systematic review and meta‐analysis of home fortification of complementary foods. Matern Child Nutr. 2009;5(4):283–321.

Zlotkin S, Antwi KY, Schauer C, Yeung G. Use of microencapsulated iron(II) fumarate sprinkles to prevent recurrence of anaemia in infants and young children at high risk. Bull World Health Organ. 2003;81(2):108–15.

Programmatic Guidance brief on use of Micronutrient Powders (MNP) for home fortification. Home fortification technical advisory group (HF-TAG) 2013. Accessed on September 10, 2014 from the URL: http://www.hftag.org/resource/hf-tag_program-brief-dec-2011-pdf/.

De-Regil LM, Suchdev PS, Vist GE, Walleser S, Peña-Rosas JP. Home fortification of foods with multiple micronutrient powders for health and nutrition in children under two years of age (Review). Evid Based Child Health. 2013;8(1):112–201.

MAL-ED Network Investigators, Acosta AM, Chavez CB, Flores JT, Olotegui MP, Pinedo SR, Trigoso DR, Vasquez AO, Ahmed I, Alam D, Ali A, Bhutta ZA, Qureshi, Shakoor’ S, Soofi S, Turab A, Yousafzai AK, Zaidi AK, Naushahro F, Bodhidatta , Mason CJ, Babji S, Bose A, John S, Kang G, Kurien B, Muliyil J, Haydom, T, Ahmed T, Ahmed AMS, Mondal D, Tofail F, Haque R, Hossain I, Islam M, Mahfuz M, et al. The MAL-ED Study: A Multinational and Multidisciplinary Approach to Understand the Relationship Between Enteric Pathogens, Malnutrition, Gut Physiology, Physical Growth, Cognitive Development, and Immune Responses in Infants and Children Up to 2 Years of Age in Resource-Poor Environments. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59(4):S193–206.

Ahmed T, Mahfuz M, Islam MM, Mondal D, Hossain MI, Ahmed AMS, Tofail F, Gaffar SMA, Haque R, Guerrant RL, Petri WA. The MAL-ED Cohort Study in Mirpur Bangladesh. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59 Suppl 4:S280–6.

Adu-Afarwuah S, Lartey A, Brown KH, Zlotkin S, Briend A, Dewey KG. Home fortification of complementary foods with micronutrient supplements is well accepted and has positive effects on infant iron status in Ghana. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;87(4):929–38.

Giovannini M, Sala D, Usuelli M, Livio L, Francescato G, Braga M, Radaelli G, Riva E. Double-blind, placebo-controlled trial comparing effects of supplementation with two different combinations of micronutrients delivered as sprinkles on growth, anemia, and iron deficiency in cambodian infants. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2006;42(3):306–12.

Rice EW. Rapid determination of total hemoglobin as hemiglobin cyanide in blood containing carboxyhemoglobin. Clin Chim Acta. 1967;18(1):89–91.

Ip H, Hyder SM, Haseen F, Rahman M, Zlotkin SH. Improved adherence and anaemia cure rates with flexible administration of micronutrient Sprinkles: a new public health approach to anaemia control. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2009;63(2):165–72.

Osei AK, Pandey P, Spiro D, Adhikari D, Haselow N, De Morais C, Davis D. Adding multiple micronutrient powders to a homestead food production programme yields marginally significant benefit on anaemia reduction among young children in Nepal. Matern Child Nutr. 2015. doi:10.1111/mcn.12173 [Epub ahead of print].

Menon P, Ruel MT, Loechl CU, Arimond M, Habicht JP, Pelto G, Michaud L. Micronutrient Sprinkles reduce anemia among 9- to 24-mo-old children when delivered through an integrated health and nutrition program in rural Haiti. J Nutr. 2007;137(4):1023–30.

Cook JD, Reddy MB, Burri J, Juillerat MA, Hurrell RF. The influence of different cereal grains on iron absorption from infant cereal foods. Am J Clin Nutr. 1997;65:964–9.

Walter T, Olivares M, Pizarro F, Muñoz C. Iron, anemia, and infection. Nutr Rev. 1997;55(4):111–24.

Marx JJ. Iron and infection: competition between host and microbes for a precious element. Best Pract Res Clin Haematol. 2002;15(2):411–26.

Markel TA, Crisostomo PR, Wang M, Herring CM, Meldrum KK, Lillemoe KD, Meldrum DR. The struggle for iron: gastrointestinal microbes modulate the host immune response during infection. J Leukoc Biol. 2007;81(2):393–400.

Gera T, Sachdev HP. Effect of iron supplementation on incidence of infectious illness in children: systematic review. BMJ. 2002;325(7373):1142.

Sazawal S, Black RE, Ramsan M, Chwaya HM, Stoltzfus RJ, Dutta A, et al. Effects of routine prophylactic supplementation with iron and folic acid on admission to hospital and mortality in preschool children in a high malaria transmission setting: community-based, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2006;367(9505):133–43.

Soofi S, Cousens S, Iqbal SP, Akhund T, Khan J, Ahmed I, Zaidi AK, Bhutta ZA. Effect of provision of daily zinc and iron with several micronutrients on growth and morbidity among young children in Pakistan: a cluster-randomised trial. Lancet. 2013;382(9886):29–40.

Zaman K, Baqui AH, Yunus M, Sack RB, Bateman OM, Chowdhury HR, Black RE. Association between nutritional status, cell-mediated immune status and acute lower respiratory infections in Bangladeshi children. Eur J Clin Nutr. 1996;50(5):309–14.

Acknowledgements

icddr,b acknowledges with gratitude the commitment of UVA, FNIH, FIC and BMGF to its research efforts. icddr,b also gratefully acknowledges the following donors which provide unrestricted support: Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh, the Department of Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development (DFATD), Canada; Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (Sida) and the Department for International Development, (UKAid).

Funding

This research protocol is funded by University of Virginia (UVA) with support from MAL-ED Network Investigators in the Foundation of National Institute of Health (FNIH), Fogarty International Centre (FIC) with overall support from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation (BMGF).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

TA, MM and AA designed the study, and prepared the manuscript. MM, MA, M. JR performed the analysis, MI, NC, MH, DM and RH provided revision of the final manuscript. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Mahfuz, M., Alam, M.A., Islam, M.M. et al. Effect of micronutrient powder supplementation for two and four months on hemoglobin level of children 6–23 months old in a slum in Dhaka: a community based observational study. BMC Nutr 2, 21 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40795-016-0061-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40795-016-0061-y