Abstract

Background

Marine sponges are diverse and functionally important members of marine benthic systems, well known to harbour complex and abundant symbiotic microorganisms as part of their species-specific microbiome. Changes in the sponge microbiome have previously been observed in relation to natural environmental changes, including nutrient availability, temperature and light. With global climate change altering seasonal temperatures, this study aims to better understand the potential effects of natural seasonal fluctuations on the composition and functions of the sponge microbiome.

Results

Metataxonomic sequencing of two marine sponge species native to the U.K. (Hymeniacidon perlevis and Suberites massa) was performed at two different seasonal temperatures from the same estuary. A host-specific microbiome was observed in each species between both seasons. Detected diversity within S. massa was dominated by one family, Terasakiellaceae, with remaining dominant families also being detected in the associated seawater. H. perlevis demonstrated sponge specific bacterial families including aforementioned Terasakiellaceae as well as Sphingomonadaceae and Leptospiraceae with further sponge enriched families present.

Conclusions

To our knowledge, these results describe for the first time the microbial diversity of the temperate marine sponge species H. perlevis and S. massa using next generation sequencing. This analysis detected the presence of core sponge taxa identified in each sponge species was not changed by seasonal temperature alterations, however, there were shifts observed in overall community composition due to fluctuations in less abundant taxa, demonstrating that microbiome stability across seasons is likely to be host species specific.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Marine sponges have developed close associations with microorganisms, harbouring large quantities of complex symbiotic microbial communities including archaea, algae, cyanobacteria and diverse heterotrophic bacteria [1]. Microorganisms can make up around 40% of the sponge biomass, two times higher than microbial numbers in seawater [2], often differing markedly from associated benthic microbial communities [3]. As sessile filter feeders [4] marine sponges are in constant interaction with the surrounding seawater however, sponges have been shown to harbour distinct sponge associated bacterial communities which are often linked to sponge specific-functions [5]. Dominant sponge associated taxa include the phyla Proteobacteria, Chloroflexi, Acidobacteria, Cyanobacteria and candidate phylum Poribacteria [6] which can be undetected in or present at low abundances in seawater [7] and previous work has also shown that marine sponges can contain unique bacterial populations that are highly abundant within only one specific sponge species [8, 9]. Whilst others have been shown to more closely resemble the community composition in the surrounding seawater with taxa which are phylogenetically similar to seawater communities and no species-specific relationships being detected [8, 10].

The majority of work characterising the sponge microbiome has been limited to the collection of the host species at a single time point [11], therefore, often the resulting information on associated microorganisms is static, not reflecting any potential shifts or changes within the microbiome [12]. There are numerous environmental changes likely to affect sponge communities including temperature changes [13] as well as differing ecological pressures. Species demonstrating close associations with the associated seawater due to abiotic factors such as location or biotic factors such as internal sponge morphology and high seawater filtering rate [14] may be affected on a microbial community composition level by changes in the surrounding environment. Conversely, other species which are comparatively less closely associated with the surrounding water column (due to differing ecological constraints e.g. the sponge location in the subtidal or intertidal zone), may be affected differently [15].

Changes in the sponge microbiome have previously been assessed in relation to temperature-related changes for seasonal and extreme temperature fluctuations and also other abiotic factors [16,17,18,19,20,21,22], some demonstrating high levels of stability [19, 20], and others wherein shifts and disruptions have been observed within the associated microbial communities [16–17, 21–22]. Even minor and naturally occurring variations in environmental conditions can markedly affect organisms [23] which has been demonstrated in tropical, temperate and cold-water sponge species [16,17,18,19,20,21,22]. The sponges examined have different preferred environmental niches, although both are submerged at high tide and exposed at low tide S. massa is found in deeper, fast flowing water areas [24] and H. perlevis found in shallow, slower flowing water [25] in the intertidal zone of the Bosham estuary and Chichester Harbour. In order to better understand the resilience of the sponge microbiome and its complexity, assessing how these communities change over time with differing environmental conditions is key. To fulfil this aim, this present study examines the effect of seasonal changes in temperate sponges located on the South Coast of the U.K.

Methods

Sampling and sample processing

Non-fatal samples of five sponges of each two species (Hymeniacidon perlevis, Suberites massa) were collected along a transect from the intertidal zone at Bosham Harbour (50.8290° N, 0.8577° W) with 1 L of sea water samples from each sponge collection site using sterile sodium thiosulphate (20 mg/L) bottles (VWR). Sampling was undertaken during two timepoints: July-August (ambient temperature 22 °C, water temperature 22–24 °C, pH 6) (these samples are subsequently referred to as T24 or T22 for temperature 22–24 °C) and October-November (ambient temperature 14 °C, water temperature 15 °C, pH 6) (these samples are subsequently referred to as T15 for temperature 15 °C) with five sponge samples taken at each timepoint, along with 1 L of seawater associated with each replicate sampling site at each individual timepoint collected ≤ 1 m from each sponge sampling site. Due to the tidal variation sample collection was carried out at water depths between 0.02 and 0.9 m. Sponge and seawater samples were collected aseptically and immediately transported to the laboratory for analysis. Sponge samples were rinsed in sterile artificial seawater (ASW) [26], debris was removed, followed by a further wash step with sterile ASW and a representative fragment of tissue (ensuring a complete cross-section of the specimen) was cut using a sterile scalpel. Resulting dissected samples were stored at -80 °C. Seawater samples (1 L) were filtered through cellulose nitrate filters (0.22 μm) (Sigma) and filters stored at -80 °C. Sterile dH20 was filtered as previously described to act as a negative control for further sequencing analysis.

DNA extraction

For next generation sequencing DNA was extracted from homogenised sponge samples and water filters using QIAamp PowerFecal Pro DNA kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. An additional incubation step was added prior to homogenisation in order to increase DNA yields: samples were incubated at 65 °C for 10 min (inverted by hand three times after 5 min) and transferred onto ice. The homogenisation protocol was altered to a speed setting of 4 for 30 s using FastPrep-24 5G homogeniser (MP Biomedicals), pause on ice 5 min and homogenisation repeated as before.

Sponge species identification

In order to allow visualisation of spicules, samples were prepared [27] and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) analysis was carried out using Zeiss digital scanning electron microscope (Zeiss Evo LS25). Initial visualisation of spicules confirmed sponge samples collected were different species with one species demonstrating smaller microxea spicules (Figure S1A,B) in comparison to the second species with comparatively larger microtylostyle spicules (Figure S1C,D) [28]. Sanger sequencing of the 28S rRNA gene (Eurofins Genomics, Ebersberg, Germany) was carried out with primers C2 (GAAAAGAACTTTGRARAGAGAGT) and D2 (TCCGTGTTTCAAGACGGG) [29] and sponge species were identified as Hymeniacidon perlevis and Suberites massa following BLAST analysis (sharing 97.43% and 97.18% with accessions MF685334.1 and HQ379249.1 respectively). The raw sequence files were deposited in the Sequence Read Archive NCBI repository under BioProject ID PRJNA922550.

16S rRNA gene sequencing

The V3-V4 region of the bacterial 16S rRNA gene was amplified from genomic DNA extracted from Hymeniacidon perlevis, Suberites massa and associated seawater at each seasonal temperature point. Next generation sequencing was carried out by LGC Genomics (Berlin, Germany) using the Illumina MiSeq V3 platform. DNA (25 µL) of concentration 1–10 ng/ µL was amplified using bacterial primers 341F (CCTACGGGNGGCWGCAG) and 785R (GACTACHVGGGTATCTAAKCC) [30]. Negative controls (with no sample added) were used for both PCR amplification and Illumina sequencing in order to assess presence of contamination. The raw sequence datasets were deposited in the Sequence Read Archive NCBI repository under BioProject ID PRJNA922550.

Taxonomic and statistical analysis

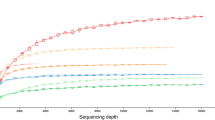

Primers and barcodes were removed from demultiplexed raw FASTQ files using Cutadapt v 4.2 [31] in Python v 3.8.15. Sequence quality was assessed using DADA2 [32] in R Studio 1.4.2 v 4.2.2. Forward and reverse quality was plotted and filtered to 260 and 240 respectively. DADA2 was used to trim and filter sequences, predict and correct Illumina sequencing error rates and merge sequences. Samples were individually checked for chimeras using the removeBimeraDenovo function and identified chimeric sequences were subsequently removed from the dataset. Input, filtered, denoised, merged and non-chimeric sequences were tracked throughout the pipeline. Sequences were grouped into features based on 100% sequence similarity, subsequently referred to as ASV (amplicon sequence variants). Taxonomic assignments of ASVs remaining after above filtering steps were classified using SILVA v123 99% Operational Taxonomic Units. Non-bacterial and archaeal (including Chloroplast and Mitochondria) derived sequence reads and singletons were removed from the dataset, low prevalence taxa were filtered by removing ASVs of a low abundance (with a minimum prevalence of 2 ASVs) and the feature table was rarefied to an even sequencing depth (18,606 reads from H. perlevis and S. massa, 9,096 reads from H. perlevis and associated seawater and 16,664 reads from S. massa and associated seawater).

All diversity and statistical analyses were performed in R Studio 1.4.2 v 4.2.2 using vegan, phyloseq and microeco packages [33,34,35]. Following rarefaction, the richness of samples was analysed using observed diversity and alpha diversity indices (Shannon index, Simpson index). In order to determine significance of differences between alpha diversity indices Kruskal-Wallis one way ANOVA and Dunn’s Kruskal-Wallis Multiple Comparisons test was carried out in R Studio 1.4.2 v 4.2.2. Principal component analysis (PCoA) based upon Bray Curtis distance metrics was carried out in order to assess the similarities and dissimilarities between samples and within groups. Permutational multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA) (P = ≤ 0.01), [36] was conducted in R package vegan [33] using Bray Curtis similarity matrix from transformed abundance data to test the significance of bacterial community dissimilarities. Core bacterial taxa were determined based on 100% prevalence (present in all replicates) and 0.01% relative abundance [37, 38]. All graphs were created in R Studio 1.4.2 v 4.2.2 using ggplot2, phyloseq and microeco packages [33–35, 39].

Results

Sponge species were identified as Hymeniacidon perlevis and Suberties massa following visualisation of spicules and 23 S rRNA sequencing. A total of 2,123,269 Illumina reads were obtained from H. perlevis and surrounding seawater of which 1,427,031 remained after quality checks and filtering steps. From S. massa and associated seawater 2,538,379 total Illumina reads were obtained after which 1,791,114 remained after quality filtering (Table S1).

Data was subsampled (Figure S2) to the minimum read depth however, a number of samples, such as H. perlevis (particularly from 24 °C), had higher numbers of detected ASVs (ASV curves have not reached a plateau at the minimum read depth) and the diversity of these may not be fully represented in subsampled data. Permutational multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA) results (Table S4) show significant differences between all samples aside from between samples of H. perlevis from each seasonal timepoint, indicating dissimilarities in bacterial community composition.

Species-specificity

When observed and Alpha diversity measures (Shannon index, Simpson index) were applied to analyse diversity within samples (Fig. 1) there were no significant differences in terms of abundance (observed diversity) between samples of H. perlevis and S. massa however H. perlevis samples demonstrated higher Shannon and Simpson diversity indices than S. massa samples (Fig. 1A; Table S2; Table S3). Beta diversity assessing diversity between samples show clear differences in diversity clustering and values detected between samples of each sponge, with samples of H. perlevis (Fig. 2A; Figure S2A) demonstrating similarities in bacterial composition across samples in comparison to samples of S. massa which clearly clustered apart from samples of H. perlevis (Fig. 2A).

Alpha diversity matrices (observed, Shannon diversity index, Simpson diversity index) for A) H. perlevis and S. massa, B) H. perlevis and associated seawater and C) S. massa and associated seawater. Significant differences between each group are measured by Kruskal-Wallis one-way ANOVA (*= p ≤ 0.05, **= p ≤ 0.01, ns = not significant). Full alpha diversity values and statistics can be found in Supplementary Tables 2–3.

Principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) of A) H. perlevis and S. massa, B) H. perlevis and associated seawater and C) S. massa and associated seawater. X and Y axis’ represent coordinates of the greatest sources of variation within datasets representing A) 7.9% and 67.8% B) 13.3% and 48.2% and C) 23.5% and 46.6% respectively.

Community composition at phylum level (Table S5) was similar between both sponge hosts, with the majority of diversity in all samples consisting of Proteobacteria (67.8–74.6% in H. perlevis and 77.2–82.1% in S. massa) followed by Bacteroidiota, Planctomycetota and Actinobacteriota though these accounted for less diversity. Samples of H. perlevis demonstrated higher detected relative abundance (1.7–3.6%) of the phylum Spirochaetota in terms of relative abundance in comparison to S. massa (0.4–0.9%) though these differences were not significant (P = 0.12). At class level (Fig. 3A; Table S5) samples of S. massa were dominated by Alphaproteobacteria (65.6–74.9%) at significantly higher numbers (P = < 0.001) than samples of H. perlevis (30-33.3%). The second dominant class Gammaproteobacteria comprised a comparatively higher detected relative abundance within H. perlevis (28–37%) in comparison to S. massa (7.2–11.4%) (P = < 0.001). Both sponge species demonstrated comparable numbers of Bacteroidia (8.8–14% in H. perlevis and 8.9–11.4% in S. massa), H. perlevis specific class (undetected within samples of S. massa) Leptospirae varied from an average of 1.7–3.6% relative abundance within samples of H. perlevis.

Despite similarities in diversity detected at phylum and class level (Fig. 3A) H. perlevis demonstrated a comparatively more complex microbiome at family level (Fig. 4A) with sponge specific and sponge enriched families present, wherein sponge specific refers to families only detected within the sponge samples which were absent from or undetected in surrounding water samples and sponge enriched refers to families which were also detected in surrounding water samples but accounted for significantly less diversity. Both sponges demonstrated high levels of Flavobacteriaceae (Flavobacteriia) and Terasakiellaceae (Alphaproteobacteria) with numbers of Terasakiellaceae being significantly higher (P = 0.001) within samples of S. massa (57.3–67.2% in S. massa in comparison to 17.1–18.6% in H. perlevis) (Table S8). H. perlevis specific families included SAR 116 (Alphaproteobacteria), Leptospiraceae (Spirochaetota) and Sphingomonadaceae (Alphaproteobacteria) not being detected within samples of S. massa. S. massa samples demonstrated higher detected relative abundance of the families Cyclobacteriaceae (Cytophagia) and Cyanobiaceae (Cyanobacteria) (P = 0.01, P = 0.05 respectively).

Microbiome composition

No significant differences were detected in observed diversity, richness/ evenness (Shannon diversity index) or distribution of species when also considering abundance (Simpson’s diversity index) between samples of H. perlevis and associated seawater samples (Fig. 1B; Table S2; Table S3). However, similarly to significantly higher detected richness when compared to samples of H. perlevis, seawater samples also demonstrated higher Shannon and Simpson values than samples of S. massa (Fig. 1C; Table S2; Table S3). Distance values and clusters between samples of H. perlevis and associated seawater (Fig. 2B) demonstrated a clear distinction between sponge and water samples, with both H. perlevis and S. massa samples demonstrating a distinct microbiome composition both from their associated seawater samples and from the other sponge host, with intra-species samples clustering closely together (Fig. 2B and C; Figure S2B; Figure S2C). Furthermore, water samples were grouped together, albeit with more variability shown between samples of seawater taken at 15 °C.

When comparing the sponge communities to the surrounding water column H. perlevis was dominated by Proteobacteria (Alphaprotebacteria followed by Gammaproteobacteria), and Bacteroidiota (Bacteroidia) which accounted for the majority of relative abundance in each of the H. perlevis samples (Fig. 3B; Table S6) and were the same dominant phyla and classes observed in seawater samples. Dominant families which were detected in H. perlevis include Flavobacteriaceae (Flavobacteriia), Rhodobacteraceae (Alphaproteobacteria) and Terasakiellaceae (Alphaproteobacteria) (Fig. 4B; Table S8). In comparison the community composition in surrounding seawater consisted of significantly higher numbers of Flavobacteriaceae (P = 0.01) and Rhodobacteraceae (P = 0.003) as well as Cryomorphaceae (Flavobacteriia) (P = 0.009) with variation between samples of seawater taken at 15 °C. Sponge specific families included Leptospiraceae (Spirochaetia), Sphingomonadaceae (Alphaproteobacteria) and an unidentified family of the order Dadabacteriales which were associated only with the sponge host and not detected in the surrounding seawater (Table S9).

S. massa samples were also shown to contain a high proportion of Proteobacteria (predominantly Alphaproteobacteria accounting for 63-74.3% of the detected relative abundance) and Bacteroidiota (Bacteroidia compromised a mean of 8.8% detected relative abundance), which were the same dominant phyla and classes in seawater samples (Fig. 3C). Proteobacteria, Bacteroidiota, and Planctomycetota were the three dominant phyla in water samples however seawater replicates show variation between timepoints (Fig. 4C; Table S6).

The sponge specific family Terasakiellaceae (Alphaproteobacteria) accounts for the majority of the detected relative abundance in S. massa samples (54.9–66.6%) followed by Flavobacteriaceae (Flavobacteriia) (7.2–7.6%) (Fig. 4C; Table S9), also detected in seawater samples. Sponge samples also contained sponge enriched families Cyclobacteriaceae (Cytophagia) and Cyanobiaceae (Cyanobacteria), these were detected at significantly higher numbers than in seawater (P = 0.009 and P = 0.002 respectively). Seawater samples were generally dominated by Flavobacteriaceae and Rhodobacteraceae (Alphaproteobacteria), with these families also being present in S. massa samples, but in a lower proportion than in seawater samples (Fig. 4C; Table S10) with significantly fewer counts of Rhodobacteraceae (P = 0.01).

Seasonal stability

Whilst there were no significant differences detected in observed diversity, evenness of species (Shannon index) or distribution of species considering abundance (Simpson’s index) (Fig. 1A). Samples taken between seasons show no clear separation for samples of H. perlevis (Fig. 2A) indicating comparable bacteria community compositions. At phylum level, the same five phyla remained dominant Proteobacteria, Bacteroidiota, Planctomycetota, Actinobacteriota and Spirochaetota (Table S5). However, in H. perlevis samples taken at 15 °C the average relative abundances for Gammaprotebacteria (Proteobacteria) and Leptospirae (Spirochaetota) increased from 28 to 37% and 1.7–3.6% respectively (P = 0.01, P = 0.3 respectively) with Parcubacteria (Pastescibacteria) falling from 2% to 24 °C to 0.6% at 15 °C (P = 0.001). At family level no significant differences were observed in relative abundance between dominant families associated with H. perlevis samples at both seasons (Table S8). Additionally, no changes in detected relative abundance of core bacterial taxa were observed at each season with a total of 69.3% detected relative abundance (made up of 807 ASVs) being shared between H. perlevis in both seasons (Figure S4B).

No significant differences were observed in abundance of species, species richness or evenness between samples of S. massa at different seasonal temperatures (Fig. 1A). However, whilst replicates of samples cluster closely, there is a separation (Fig. 2A) between those taken in the warmer season (22 °C) and those taken in the cooler season (15 °C) suggesting inter-seasonal differences in community composition (P = 0.008) with those taken at the colder temperature (15 °C) showing more variability between replicates in comparison to the warmer temperature (22 °C). The same three classes remained dominant Alphaproteobacteria, Bacteroidia and Gammaproteobacteria (Table S5) with both Gammaproteobacteria and Bacteroidia increasing in terms of relative abundance in the cooler (15 °C) season (from 7.2 to 11.4% and 8.9–11.4% respectively) and Alphaproteobacteria decreasing (from 74.9 to 65.6%), although none of these differences were statistically significant. At family level Terasakiellaceae and Flavobacteriaceae remained dominant with non-significant differences between seasons (Table S9). Shifts in proportions of family Cyanobiaceae were observed demonstrating higher numbers (from 1.7 to 0.2% detected relative abundance) in sponge samples from the warmer (T22°C) time point (P = 0.01). A total of 68.8% of the detected relative abundance (made up of 624 ASVs) being shared between S. massa at different seasons (Figure S4C).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this study presents the first NGS based examination of microbial diversity in the temperate sponges H.perlevis and S.massa. As previously observed in other sponge species [40, 41] H. perlevis and S. massa samples were dominated by Proteobacteria (Alpha- followed by Gamma) and Bacteroidiota which were also detected within seawater samples. These phyla have previously been detected in cold water sponges, particularly Antarctic sponges [42, 43], accounting for a large proportion of bacterial relative abundance. With further previous work [44] showing that Alpha- and Gamma-proteobacteria account for high amounts of culturable diversity within H. perlevis.

In S. massa the majority of detected relative abundance was accounted for by one family (Terasakiellaceae), which was also detected in samples of H. perlevis but as a smaller proportion of the overall observed population. This family, which in both species, is sponge-specific has previously been associated with marine sponges [45], accounting for similarly large proportion of the sponge microbiome as well as in other marine organisms including coral [46, 47]. While the exact functional role this family play in the sponge is not yet established, they are hypothesised to be involved in nitrogen cycling [46], of which marine host associated microbial communities including those of sponges are known to play a key role [48]. As in S. massa, Terasakiellaceae accounts for large proportions of bacterial abundance in other marine sponges (Clathria prolifera and Halichondria bowerbanki from the Mid Atlantic) [44] alongside Flavobacteriaceae (also detected in S. massa and H. perlevis), suggesting these families could be stable members of some sponge microbiomes regardless of sponge species or geographical location.

Differences are apparent in terms of the presence of higher numbers of sponge specific and enriched families within the microbiome of H. perlevis in comparison to S. massa. The family Sphingomonadaceae detected in H. perlevis but not in S. massa, has previously been demonstrated to be dominant in marine sponge Rhopaloeides odorabile [49]. Families of the order Sphingomondales are known to form close relationships with marine sponges and have been linked to vitamin B12 synthesis via functional metagenomics [50]. Additionally, the presence species of Sphingomonadaceae have previously been demonstrated to enhance degradation rates of artificial chemicals such as Bisphenol A [51]. As H. perlevis has been shown to have a high capacity for bioaccumulation of pollutants [52] this contrasting ecological condition could go some way to explaining the presence of Sphingomonadaceae in H. perlevis and not S. massa. However, previous links to marine sponges and associations with vitamin synthesis [49, 50] may conversely suggest that whilst members of this family do not always account for large amounts of overall abundance their role in the sponge microbiome is important and shared across certain sponge species.

These differences in microbiome composition (i.e. the presence of more sponge enriched and specific families within the microbiome of H. perlevis) may be accounted for by differences in sponge morphology, for example size or density of mesohyl tissues and narrower water filtering canals [55] as well as contrasting ecological pressures. Species of Suberites, which are primarily located in sub and intertidal zones, have previously been suggested to have their entire nutritional needs met by bacterial uptake [56]. This is probably due to a high filtering rate [57] which is likely to have an effect upon both the sponge host and the resident microbial communities. H. perlevis, however, is primarily located in rocky, intertidal areas often semi enclosed/enclosed waters and polluted areas, such as ports and harbours [58, 59] with these contrasts in environmental parameters being likely to have an impact upon community composition.

Further contrasting ecological parameters including temperature have been shown to lead to variations in sponge symbionts irrespective of location [60] and may affect, or even determine the symbiotic community with the ability to quickly acclimatise to environmental change essential to sessile organisms [4]. Variations and shifts in environmental conditions can have marked effects on organisms and their physiology [14] and thus can have varying impacts on the associated microbiome which has previously been demonstrated in tropical and temperate sponge species [16, 17, 21, 22]. Previous work has assessed the stability of various sponge microbiomes across geographical and seasonal changes, for example, in reefs off the coast of Florida [61] wherein slight shifts in bacterial taxa were observed including changes in the numbers of Alphaproteobacteria, Gammaproteobacteria and Cyanobacteria across seasons, similarly to both H. perlevis and S. massa (although the differences in these numbers were not significant). When assessing seasonal stability from spring to autumn of sponge species the Caribbean Sea [62] significant differences were detected between microbial community structure at each season. High levels of variability in the same sponge species across seasons has been observed [12, 13] and this variability has also been demonstrated in other species of Hymeniacidon [63]. Whilst shifts were apparent in bacterial community composition these may be attributed to transient or ‘generalist’ bacterial associations as differences within the dominant microbial diversity at family level between H. perlevis samples at each season were not found to be significant in terms of detected relative abundance suggesting stability of dominant core H. perlevis taxa (69.3% shared between seasons) irrespective of environmental changes such as temperature or changes in the diversity of the surrounding water column. Despite observed changes in the bacterial diversity of the surrounding water column and seasonal changes as well more variability observed between microbial community similarity in samples taken at the cooler temperature in comparison to the warmer temperature, 68.8% of the detected relative abundance was shared between samples of S. massa at each season. As with H. perlevis, slight shifts in detected relative abundance of families were not found to be significant, aside from significantly higher numbers of the family Cyanobiaceae at the warmer (22 °C). Cyanobacterial sponge symbionts have previously been observed to fluctuate across seasons [61] likely due to changes in light availability. The overall microbial community composition in both sponge species appeared to be stable, with minimal significant differences (aside from aforementioned Cyanobiaceae in S. massa) in dominant sponge associated families. Differences were observed in bacterial community composition of S. massa samples from each season, however core dominant taxa were stable. Detected diversity consisted mainly of sponge-specific Terasakiellaceae in both seasonal temperatures with this study suggesting this family to be a stable member of both the S. massa and H. perlevis microbiomes. Observed shifts in bacterial community composition in samples of S. massa between seasonal temperatures, whilst this may be attributed to changes in transient associated bacterial communities or ‘generalist’ populations as well as sponge enriched Cyanobiaceae, may also be related to host species or related ecological pressures e.g. close association with surrounding seawater. These results suggest, as per previous work assessing the responses of sponges to varying temperature changes including implications for climate change [64], that the temperature response of sponge microbiomes to seasonal change is likely to be sponge-species-specific as well as dependent upon the extremity of the temperature to which they are exposed.

Conclusions

Similar to other sponge phyla [40, 41] samples of H. perlevis were dominated by Proteobacteria (Alpha- and Gamma-), and Bacteroidiota (Bacteroidia) accounting for the majority of detected relative abundance. This is similar to cold-water sponges e.g. Antarctic sponges [42, 43]. Differences in species richness and microbiome complexity at family level were observed, with H. perlevis demonstrating more sponge enriched and sponge specific communities differing from the community composition of the surrounding seawater. Whereas within S. massa the majority of the community was Proteobacteria (of this was predominantly Alphaproteobacteria), and consisting of one sponge specific family, Terasakiellaceae.

Previous work has demonstrated seasonal variability in cultivable bacterial of other Hymeniacidon species [63] as well as shifts in terms of sponge specific symbionts such as Cyanobacteria [60]. The microbiome of H. perlevis appears to be stable in terms of detected core sponge associated taxa in relation to environmental changes such as seasonal changes. Higher diversity was observed in seawater samples in comparison to the microbial diversity of S. massa in either season, with higher Shannon and Simpson diversity indices, changes were observed in overall bacterial community composition between samples of S. massa at each season, however core families (including sponge specific Terasakiellaceae) remained dominant.

This is the first report of the microbial community associated with both of the temperate marine sponge species H. perlevis and S. massa. The understanding of the microbial community in this study, supports that the temperate sponge microbiome is species specific, and furthermore, that microbiome changes in response to seasonal temperature change are related to this host-specificity. The core taxa detected in the sponge microbiome remained stable, but fluctuations were more commonly detected in the less abundant microbial taxa. This research further assesses the impacts of natural environmental changes on the sponge holobiont, with implications for environmental health and stability related to the wider benthic functioning with which they are associated with.

Data Availability

The raw 16 S rRNA supporting the conclusions of this article is available in the Sequence Read Archive in NCBI repository under BioProject ID PRJNA922550, submission ID SUB12524464. The raw 28 S rRNA gene sequences are available under BioProject ID PRJNA922550, accession numbers SAMN33299855-SAMN33299856.

References

Webster NS, Taylor MW. Marine sponges and their microbial symbionts: love and other relationships. Environ Microbiol. 2012;14(2):335–46.

Hentschel U, Schmid M, Wagner M, Fieseler L, Gernert C, Hacker J. Isolation and phylogenetic analysis of bacteria with antimicrobial activities from the Mediterranean sponges Aplysina aerophoba and Aplysina cavernicola. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2001;35(3):305–12.

Webster NS, Taylor MW, Behnam F, Lücker S, Rattei T, Whalan S, Horn M, Wagner M. Deep sequencing reveals exceptional diversity and modes of transmission for bacterial sponge symbionts. Environ Microbiol. 2010;12(8):2070–82.

Brümmer F, Pfannkuchen M, Baltz A, Hauser T, Thiel V. Light inside sponges. J Exp Mar Biol Ecol. 2008;367(2):61–4.

Pita L, Rix L, Slaby BM, Franke A, Hentschel U. The sponge holobiont in a changing ocean: from microbes to ecosystems. Microbiome. 2018;6(1):1–18.

Simister RL, Deines P, Botté ES, Webster NS, Taylor MW. Sponge-specific clusters revisited: a comprehensive phylogeny of sponge‐associated microorganisms. Environ Microbiol. 2012;14(2):517–24.

Taylor MW, Tsai P, Simister RL, Deines P, Botte E, Ericson G, Schmitt S, Webster NS. Sponge-specific’bacteria are widespread (but rare) in diverse marine environments. ISME J. 2013;7(2):438–43.

Blanquer A, Uriz MJ, Galand PE. Removing environmental sources of variation to gain insight on symbionts vs. transient microbes in high and low microbial abundance sponges. Environ Microbiol. 2013;15(11):3008–19.

Taylor MW, Schupp PJ, Dahllöf I, Kjelleberg S, Steinberg PD. Host specificity in marine sponge-associated bacteria, and potential implications for marine microbial diversity. Environ Microbiol. 2004;6(2):121–30.

Ribes M, Dziallas C, Coma R, Riemann L. Microbial diversity and putative diaztrophy in high- and low-microbial-abundance Mediterranean sponges. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2015;81(17):5683–93.

Erwin PM, Pita L, López-Legentil S, Turon X. Stability of sponge-associated bacteria over large seasonal shifts in temperature and irradiance. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2012;78(20):7358–68.

Anderson SA, Northcote PT, Page MJ. Spatial and temporal variability of the bacterial community in different chemotypes of the New Zealand marine sponge Mycale hentscheli. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2010;72(3):328–42.

Fan L, Liu M, Simister R, Webster NS, Thomas T. Marine microbial symbiosis heats up: the phylogenetic and functional response of a sponge holobiont to thermal stress. ISME J. 2013;7(5):991–1002.

Turon M, Cáliz J, Garate L, Casamayor EO, Uriz MJ. Showcasing the role of seawater in bacteria recruitment and microbiome stability in sponges. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):15201.

Weigel BL, Erwin PM. Intraspecific variation in microbial symbiont communities of the sun sponge, Hymeniacidon heliophila, from intertidal and subtidal habitats. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2016;82(2):650–8.

Lemoine N, Buell N, Hill A, Hill M. (2007). Assessing the utility of sponge microbial symbiont communities as models to study global climate change: a case study with Halichondria bowerbanki. Porifera Research: Biodiversity Innovation and Sustainability, 419–25. https://www.natelemoine.com/pdfs/Lemoine%20et%20al%202008.pdf.

Webster NS, Cobb RE, Negri AP. Temperature thresholds for bacterial symbiosis with a sponge. ISME J. 2008;2(8):830–42.

Luter HM, Andersen M, Versteegen E, Laffy P, Uthicke S, Bell JJ, Webster NS. Cross-generational effects of climate change on the microbiome of a photosynthetic sponge. Environ Microbiol. 2020;22(11):4732–44.

Cárdenas CA, Font A, Steinert G, Rondon R, González-Aravena M. Temporal stability of bacterial communities in Antarctic sponges. Front Microbiol. 2019;10:2699.

Luter HM, Gibb K, Webster NS. Eutrophication has no short-term effect on the Cymbastela stipitata holobiont. Front Microbiol. 2014;5:216.

Wichels A, Würtz S, Döpke H, Schütt C, Gerdts G. Bacterial diversity in the breadcrumb sponge Halichondria panicea (Pallas). FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2006;56(1):102–18.

Ramsby BD, Hoogenboom MO, Whalan S, Webster NS. Elevated seawater temperature disrupts the microbiome of an ecologically important bioeroding sponge. Mol Ecol. 2018;27(8):2124–37.

Kazmi SSUH, Wang YYL, Cai YE, Wang Z. Temperature effects in single or combined with chemicals to the aquatic organisms: an overview of thermo-chemical stress. Ecol Ind. 2022;143:109354.

Dyrynda P. (2005). 8. Sub-tidal ecology of Poole Harbour—An overview. Proceedings in Marine Science, 7, 109–130. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1568-2692(05)80013-0.

Turner TL. (2020). The marine sponge Hymeniacidon perlevis is a globally-distributed invasive species. bioRxiv, 2020-02. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.02.13.948000.

Harrison PJ, Waters RE, Taylor FJR. A broad-spectrum artificial sea water medium for coastal and open ocean phytoplankton 1. J Phycol. 1980;16(1):28–35.

Smith DG. First report of a freshwater sponge (Porifera: Spongillidae) from the West Indies. J Nat Hist. 1994;28(5):981–6.

Łukowiak M, Van Soest R, Klautau M, Pérez T, Pisera A, Tabachnick K. The terminology of sponge spicules. J Morphol. 2022;283(12):1517–45.

Chombard C, Boury-Esnault N, Tillier S. Reassessment of homology of morphological characters in tetractinellid sponges based on molecular data. Syst Biol. 1998;47(3):351–66

Klindworth A, Pruesse E, Schweer T, Peplies J, Quast C, Horn M, Glöckner FO. Evaluation of general 16S ribosomal RNA gene PCR primers for classical and next-generation sequencing-based diversity studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41(1):e1–e1.

Martin M. Cutadapt removes adapter sequences from high-throughput sequencing reads. EMBnet J. 2011;17(1):10–2.

Callahan BJ, McMurdie PJ, Rosen MJ, Han AW, Johnson AJA, Holmes SP. DADA2: high-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat Methods. 2016;13(7):581–3.

Dixon P. VEGAN, a package of R functions for Community Ecology. J Veg Sci. 2003;14(6):927–30.

McMurdie PJ, Holmes S. Phyloseq: an R package for reproducible interactive analysis and graphics of microbiome census data. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(4):e61217.

Liu C, Cui Y, Li X, Yao M. microeco: an R package for data mining in microbial community ecology. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2021;97(2):fiaa255.

Anderson MJ. A new method for non-parametric multivariate analysis of variance. Austral Ecol. 2001;26(1):32–46.

Astudillo-García C, Bell JJ, Webster NS, Glasl B, Jompa J, Montoya JM, Taylor MW. Evaluating the core microbiota in complex communities: a systematic investigation. Environ Microbiol. 2017;19(4):1450–62.

Shade A, Handelsman J. Beyond the Venn diagram: the hunt for a core microbiome. Environ Microbiol. 2012;14(1):4–12.

Wickham H. ggplot2. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Computational Statistics. 2011;3(2):180–5.

Li ZY, Liu Y. Marine sponge Craniella austrialiensis-associated bacterial diversity revelation based on 16S rDNA library and biologically active Actinomycetes screening, phylogenetic analysis. Lett Appl Microbiol. 2006;43(4):410–6.

Li Z, He L, Miao X. Cultivable bacterial community from South China Sea sponge as revealed by DGGE fingerprinting and 16S rDNA phylogenetic analysis. Curr Microbiol. 2007;55(6):465–72.

Rodríguez-Marconi S, De la Iglesia R, Díez B, Fonseca CA, Hajdu E, Trefault N. Characterization of bacterial, archaeal and eukaryote symbionts from Antarctic sponges reveals a high diversity at a three-domain level and a particular signature for this ecosystem. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(9):e0138837.

Steinert G, Wemheuer B, Janussen D, Erpenbeck D, Daniel R, Simon M, Brinkhoff T, Schupp PJ. Prokaryotic diversity and community patterns in Antarctic continental shelf sponges. Front Mar Sci. 2019;6:297.

Alex A, Silva V, Vasconcelos V, Antunes A. Evidence of unique and generalist microbes in distantly related sympatric intertidal marine sponges (Porifera: Demospongiae). PLoS ONE. 2013;8(11):e80653.

Sacristán-Soriano O, Winkler M, Erwin P, Weisz J, Harriott O, Heussler G, Brauer E, Marsden BW, Hill A, Hill M. Ontogeny of symbiont community structure in two carotenoid‐rich, viviparous marine sponges: comparison of microbiomes and analysis of culturable pigmented heterotrophic bacteria. Environ Microbiol Rep. 2019;11(2):249–61.

Weiler BA, Verhoeven JT, Dufour SC. Bacterial communities in tissues and surficial mucus of the cold-water coral Paragorgia arborea. Front Mar Sci. 2018;5:378.

Parker KE, Ward JO, Eggleston EM, Fedorov E, Parkinson JE, Dahlgren CP, Cunning R. Characterization of a thermally tolerant Orbicella faveolata reef in Abaco, the Bahamas. Coral Reefs. 2020;39(3):675–85.

Hanz U, Riekenberg P, de Kluijver A, van der Meer M, Middelburg JJ, de Goeij JM, Bart MC, Wurz E, Colaco A, Duineveld GCAR, Reichart G, Rapp H, Mienis F. The important role of sponges in carbon and nitrogen cycling in a deep-sea biological hotspot. Funct Ecol. 2022;36(9):2188–99.

Tout J, Astudillo-García C, Taylor MW, Tyson GW, Stocker R, Ralph PJ, Seymour JR, Webster NS. Redefining the sponge‐symbiont acquisition paradigm: sponge microbes exhibit chemotaxis towards host‐derived compounds. Environ Microbiol Rep. 2017;9(6):750–5.

Thomas T, Rusch D, DeMaere MZ, Yung PY, Lewis M, Halpern A, Heidelberg KB, Egan S, Steinberg PD, Kjelleberg S. Functional genomic signatures of sponge bacteria reveal unique and shared features of symbiosis. ISME J. 2010;4(12):1557–67.

Oh S, Choi D. Microbial community enhances biodegradation of bisphenol a through selection of Sphingomonadaceae. Microb Ecol. 2019;77(3):631–9.

Mahaut ML, Basuyaux O, Baudinière E, Chataignier C, Pain J, Caplat C. The porifera Hymeniacidon perlevis (Montagu, 1818) as a bioindicator for water quality monitoring. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2013;20(5):2984–92.

Hentschel U, Piel J, Degnan SM, Taylor MW. Genomic insights into the marine sponge microbiome. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2012;10(9):641–54.

Vacelet J, Donadey C. Electron microscope study of the association between some sponges and bacteria. J Exp Mar Biol Ecol. 1977;30(3):301–14.

Poppell E, Weisz J, Spicer L, Massaro A, Hill A, Hill M. Sponge heterotrophic capacity and bacterial community structure in high-and low‐microbial abundance sponges. Mar Ecol. 2014;35(4):414–24.

Frost T. (1976). Sponge feeding: a review with a discussion of some continuing research. Aspects of Sponge Biology (F. Harrison and R. Cowden, editors). Academic Press, New York, 283–293.

Jørgensen CB. On the relation between water transport and food requirements in some marine filter feeding invertebrates. Biol Bull. 1952;103(3):356–63.

Longo C, Corriero G, Licciano M, Stabili L. Bacterial accumulation by the Demospongiae Hymeniacidon perlevis: a tool for the bioremediation of polluted seawater. Mar Pollut Bull. 2010;60(8):1182–7.

Corriero G, Gherardi M, Giangrande A, Longo C, Mercurio M, Musco L, Marzano CN. Inventory and distribution of hard bottom fauna from the marine protected area of Porto Cesareo (Ionian Sea): Porifera and Polychaeta. Italian J Zool. 2004;71(3):237–45.

Alex A, Vasconcelos V, Tamagnini P, Santos A, Antunes A. Unusual symbiotic cyanobacteria association in the genetically diverse intertidal marine sponge Hymeniacidon perlevis (Demospongiae, Halichondrida). PLoS ONE. 2012;7(12):e51834.

White JR, Patel J, Ottesen A, Arce G, Blackwelder P, Lopez JV. Pyrosequencing of bacterial symbionts within Axinella corrugata sponges: diversity and seasonal variability. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(6):e38204.

Villegas-Plazas M, Wos-Oxley ML, Sanchez JA, Pieper DH, Thomas OP, Junca H. Variations in microbial diversity and metabolite profiles of the tropical marine sponge Xestospongia muta with season and depth. Microb Ecol. 2019;78:243–56.

Jeong JB, Park JS. Seasonal differences of bacterial communities associated with the marine sponge, Hymeniacidon sinapium. Korean J Microbiol. 2012;48(4):262–9.

Bell JJ, Bennett HM, Rovellini A, Webster NS. Sponges to be winners under near-future climate scenarios. Bioscience. 2018;68(12):955–68.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Dr. Daniel Mompel-Riera and Josephine Herbert for assistance with preparation for data analysis and Dr. Joanne Preston and Dr. Michelle Hale for useful discussions throughout the project.

Funding

Research was supported by Expanding Excellence (E3) grant from Research England. CL was supported by a postgraduate student bursary award (31999) from the Centre for Enzyme Innovation, School of Biological Sciences at the University of Portsmouth.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.W. conceived the idea of the study. J.W. and C.L. designed experimental work and collected samples. C.L carried out collection of experimental data and performed analysis. J.W. and C.L. interpreted data. J.W. and C.L wrote the manuscript, C.L prepared all figures. J.W and C.L approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval was obtained from the University Ethics Committee (UEC) at the University of Portsmouth under Ethics Code 10140.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

JW is Editor in Chief of Environmental Microbiome- however, they were not involved in the Handling Editor or Reviewer selection processes or at any other stage of the evaluation and decision process.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Lamb, C.E., Watts, J.E.M. Microbiome species diversity and seasonal stability of two temperate marine sponges Hymeniacidon perlevis and Suberites massa. Environmental Microbiome 18, 52 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40793-023-00508-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40793-023-00508-7