Abstract

Background

The rupture of splenic artery pseudoaneurysm (SAP) is life-threatening disease, often caused by trauma and pancreatitis. SAPs often rupture into the abdominal cavity and rarely into the stomach.

Case presentation

A 70-year-old male with no previous medical history was transported to our emergency center with transient loss of consciousness and tarry stools. After admission, the patient become hemodynamically unstable and his upper abdomen became markedly distended. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography performed on admission showed the presence of a splenic artery aneurysm (SAP) at the bottom of a gastric ulcer. Based on the clinical picture and evidence on explorative tests, we established a preliminary diagnosis of ruptured SAP bleeding into the stomach and performed emergency laparotomy. Intraoperative findings revealed the presence of a large intra-abdominal hematoma that had ruptured into the stomach. When we performed gastrotomy at the anterior wall of the stomach from the ruptured area, we found pulsatile bleeding from the exposed SAP; therefore, the SAP was ligated from inside of the stomach, with gauze packing into the ulcer. We temporarily closed the stomach wall and performed open abdomen management, as a damage control surgery (DCS) approach. On the third day of admission, total gastrectomy and splenectomy were performed, and reconstruction surgery was performed the next day. Histopathological studies of the stomach samples indicated the presence of moderately differentiated tubular adenocarcinoma. Since no malignant cells were found at the rupture site, we concluded that the gastric rupture was caused by increased internal pressure due to the intra-abdominal hematoma.

Conclusions

We successfully treated a patient with intragastric rupture of the SAP that was caused by gastric cancer invasion, accompanied by gastric rupture, by performing DCS. When treating gastric bleeding, such rare causes must be considered and appropriate diagnostic and therapeutic strategies should be designed according to the cause of bleeding.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Rupture of splenic artery pseudoaneurysm (SAP) is a fatal condition [1,2,3]. SAPs are often caused by trauma and pancreatitis and bleed into the abdominal cavity, rarely rupturing into the stomach [4,5,6,7,8]. Herein, we report a rare case of SAP caused by gastric cancer invading the splenic artery, which ruptured into the stomach with hemorrhagic shock, resulting in gastric rupture because of increased intragastric pressure due to hematoma.

Case presentation

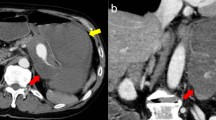

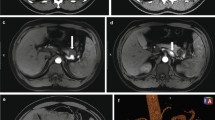

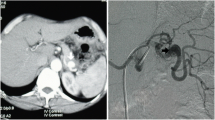

A 70-year-old male with no previous medical history was transported by ambulance to our emergency center with transient loss of consciousness and tarry stools. This patient was a smoker, not obese, and had no history of habitual eating of smoked or salted foods. The patient had mildly clouded consciousness, with pale skin and cold sweats; his upper abdomen was distended, and he had tarry stools at the emergency department on arrival. The patient’s vital signs were as follows: heart rate (HR), 138/min; blood pressure (BP), 92/59 mmHg; SpO2, 99% for oxygen setting of 6 L/min; respiratory rate, 17/min; body temperature, 36.5℃. We suspected hemorrhagic shock due to upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB), given the severe anemia with serum hemoglobin of 4.6 mg/dL and tarry stools. Therefore, we performed endotracheal intubation and emergency upper gastrointestinal endoscopy with blood transfusion. However, we could not observe distal to the esophagogastric junction owing to the presence of a filling hematoma. After the transfusion of six units of red blood cell, the patient’s vital signs stabilized (BP, 120/60 mmHg; HR, 90/min). Then, contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) was performed, followed by admission to the intensive care unit; we planned to repeat the endoscopy at a later date. Six hours after the admission, the patient become hemodynamically unstable again, and his upper abdomen became markedly distended. The contrast-enhanced CT performed on admission showed an SAP at the bottom of a gastric ulcer; therefore, the diagnosis of UGIB due to rupture of the SAP was confirmed (Fig. 1a, b). Despite massive transfusion, the vital signs remained unstable. Therefore, we selected emergency laparotomy rather than interventional radiology or upper gastrointestinal endoscopy as a hemostatic procedure. Resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta (REBOA) was placed in Zone 1, and the aorta was completely occluded until the operation room was prepared. At the start of surgery, since the patient was experiencing life-threatening bleeding (BP, 50/35 mmHg; HR, 145/min), with arterial blood pH of 7.10, we decided to perform damage control surgery (DCS). Intraoperative findings revealed a large intra-abdominal hematoma, resulting in a gastric rupture of approximately 10 cm in the anterior wall of the middle gastric body. When we performed gastrotomy from the anterior wall of the stomach from the ruptured area to the cardia, we found pulsatile bleeding from the SAP exposed at the bottom of the ulcer on the posterior wall of the upper gastric body. We ligated the artery aneurysm from inside of the stomach and performed gauze packing into the ulcer. The stomach wall was temporarily closed and open abdomen management was performed (Figs. 2, 3). The total perioperative transfusion volume was 36 units of red blood cells, 38 units of fresh frozen plasma, and 40 units of platelets.

On the third day of admission, second-look laparotomy was performed. Intraoperative findings during the second-look laparotomy indicated that the rupture in the gastric wall was too wide to be closed directly or via partial gastrectomy. In addition, the area of the splenic artery invaded by the gastric cancer was close to the splenic hilum. Therefore, we decided to perform a total gastrectomy with splenectomy. Roux-en-Y reconstruction was performed during the third-look laparotomy the next day. On the 8th day of admission, the patient showed clear consciousness and was extubated. After treatment of an intra-abdominal abscess, probably due to minor leakage of esophageal jejunal anastomosis, with antibiotics and drainage of the abscess, the patient was transferred to the hospital for rehabilitation on the 52nd day of admission.

Histopathological examination of the stomach samples indicated the diagnosis of the moderately differentiated tubular adenocarcinoma. Since no malignant cells were found at the rupture site and no other specific reason of gastric rupture in the gastric wall had been proven pathologically, we concluded that the increased intragastric pressure due to the hematoma had led to gastric rupture.

Discussion

The main causes of SAPs are trauma and pancreatitis [4]. Herein, the SAP formed at the bottom of the ulcer in a patient with gastric cancer had ruptured, which is rarely caused by direct invasion of cancer or ulcer [5,6,7]. SAPs often rupture intraperitoneally, perforating the gastrointestinal tract in less than 30% of the cases, and perforation of the stomach is even rarer, occurring in approximately 10% of the cases [8]. Bleeding of ruptured SAPs into free spaces such as the digestive tract or abdominal cavity can be fatal [9,10,11,12]. The guidelines of the Society for Vascular Surgery recommend treating SAPs with transarterial embolization (TAE) or surgery, depending on hemodynamic, location of the aneurysm, and facility capabilities [13]. In the present case, emergency surgery was performed because of the patient's unstable condition. However, if the SAP was diagnosed immediately after the CT scan, before the patient had become hemodynamically unstable, TAE could have been an effective option for hemostasis and emergency surgery could have been avoided.

Gastric rupture has been reported to be caused by trauma injuries [14,15,16]; binge-eating [17,18,19,20,21,22]; intake of excessive sodium bicarbonate [23, 24] in psychiatric patients, obstruction of the intestinal tract (e.g., superior mesenteric artery syndrome) [25,26,27,28,29]; and iatrogenic causes such as bag-mask ventilation, cardiopulmonary resuscitation, and esophageal intubation [30,31,32,33,34,35,36]. The most likely location of rupture is the lesser curvature, followed by the anterior wall. The lesser curvature is susceptible to rupture because of the weak gastric wall with few mucosal folds and poor mobility afforded by the hepatogastric ligament [23, 32]. Gastric dilation is commonly caused by the atony of gastric wall, acute gastric dilation, and mechanical obstruction such as superior mesenteric artery syndrome, resulting in gastric rupture by ischemic necrosis of the gastric wall [22, 25, 26, 37].

In our patient’s case, pathological examination revealed no invasion of cancer at the site of the rupture, and CT imaging on admission did not show gastric rupture. Therefore, the patient was diagnosed with excessive increase in intragastric pressure because of gastric rupture caused by a hematoma. The gastric rupture led to the loss of the tamponade effect, temporarily controlling the bleeding, which resulted in re-bleeding and sudden collapse of the patient’s vital signs after admission.

DCS is widely used for resuscitation of critically ill patients with severe traumatic injuries. Since patients with coagulopathy, acidosis, and/or hypothermia are at high risk of death, these conditions are included under the term “deadly triad”. DCS is a series of procedures wherein bleeding, contamination, and abdominal hypertension are controlled first; initial surgery is completed as soon as possible; and definitive surgery is performed after the management of the “deadly triad” and stabilization of the patient’s general condition in the intensive care unit [38,39,40,41,42,43]. Recently, DCS has also been reported to be useful in non-traumatic abdominal emergencies, such as intra-abdominal hemorrhage, peritonitis with septic shock, hollow viscus perforation, acute mesenteric ischemia, necrotizing enterocolitis, acute pancreatitis, and abdominal compartment syndrome [44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51]. We selected DCS, because our patient was in imminent cardiac arrest with metabolic acidosis at the time of the start of surgery and definitive surgery was expected to be complicated and lengthy. Following the principle of DCS, we performed the initial surgery only to control hemorrhage, stabilized the patient’s general condition in the intensive care unit, and then surgically reconstructed the stomach. Thus, the patient’s life was saved after this three-stage operation.

The efficacy of REBOA has also been reported in cases of hemorrhagic shock from subdiaphragmatic organs, for both traumatic and non-traumatic hemorrhage, as a method for controlling the inflow of bleeding before emergency hemostatic surgery [12, 52,53,54]. However, the indications for REBOA are controversial, as REBOA could delay the time to hemostasis, resulting in poor outcome [55]. In our patient’s case, REBOA was inserted until the operation room was prepared and did not delay the time to hemostasis. Therefore, REBOA helped prevent cardiac arrest due to hemorrhage and secure the field of view during the operation.

Conclusion

We successfully treated a patient with intragastric rupture of the SAP that was caused by gastric cancer invasion, accompanied by gastric rupture, using DCS. When treating gastric bleeding, rare causes, such as perforation of SAP, must be considered, and appropriate diagnostic and therapeutic strategies must be determined according to the cause of bleeding.

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

- SAP:

-

Splenic artery pseudoaneurysm

- HR:

-

Heart rate

- BP:

-

Blood pressure

- UGIB:

-

Upper gastrointestinal bleeding

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- REBOA:

-

Resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta

- DCS:

-

Damage control surgery

References

Trastek VF, Pairolero PC, Joyce JW, Hollier LH, Bernatz PE. Splenic artery aneurysms. Surgery. 1982;91(6):694–9.

Karaman K, Onat L, Sirvanci M, Olga R. Endovascular stent graft treatment in a patient with splenic artery aneurysm. Diagn Interv Radiol. 2005;11:119–21.

Bergert H, Hinterseher I, Kersting S, Leonhardt J, Bloomenthal A, Saeger HD. Management and outcome of hemorrhage due to arterial pseudoaneurysms in pancreatitis. Surgery. 2005;137:323–8.

Tessier DJ, Stone WM, Fowl RJ, Abbas MA, Andrews JC, Bower TC, et al. Clinical features and management of splenic artery pseudoaneurysm: case series and cumulative review of literature. J Vasc Surg. 2003;38:969–74.

Liyen CA, Uy PP, Yap JEL. Acute gastric hemorrhage due to gastric cancer eroding into a splenic artery pseudoaneurysm: two dangerously rare etiologies of upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Cureus. 2020;12: e10685.

Cho SB, Park SE, Lee CM, Park JH, Baek HJ, Ryu KH, et al. Splenic artery pseudoaneurysm with splenic infarction induced by a benign gastric ulcer: a case report. 2018;97:e11589.

Syed SM, Moradian S, Ahmed M, Ahmed U, Shaheen S, Stalin V. A benign gastric ulcer eroding into a splenic artery pseudoaneurysm presenting as a massive upper gastrointestinal bleed. J Surg Case Rep. 2014;2014:rju102.

Liu CF, Kung CT, Liu BM, Ng SH, Huang CC, Ko SF. Splenic artery aneurysms encountered in the ED: 10 years’ experience. Am J Emerg Med. 2007;25:430–6.

Yoshikawa C, Yamato I, Nakata Y, Nakagawa T, Inoue T, Nakatani M, et al. Giant splenic artery aneurysm rupture into the stomach that was successfully managed with emergency distal pancreatectomy. Surg Case Rep. 2022;8:148.

Panzera F, Inchingolo R, Rizzi M, Biscaglia A, Schievenin MG, Tallarico E, et al. Giant splenic artery aneurysm presenting with massive upper gastrointestinal bleeding: a case report and review of literature. World J Gastroenterol. 2020;26(22):3110–7.

De Silva WS, Gamlaksha DS, Jayasekara DP, Rajamanthri SD. A splenic artery aneurysm presenting with multiple episodes of upper gastrointestinal bleeding: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2017;11(1):123.

Nakata T, Okishio Y, Ueda K, Nasu T, Kawashima S, Kunitatsu K, et al. Life-threatening gastrointestinal bleeding from splenic artery pseudoaneurysm due to gastric ulcer penetration treated by surgical hemostasis with resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta: a case report. Clin Case Rep. 2022;10(3): e05561.

Chaer RA, Abularrage CJ, Coleman DM, Eslami MH, Kashyap VS, Rockman C, et al. The Society for Vascular Surgery clinical practice guidelines on the management of visceral aneurysms. J Vasc Surg. 2020;71:3S-39S.

Bruscagin V, Coimbra R, Rasslan S, Abrantes WL, Souza HP, Neto G, et al. Blunt gastric injury. A multicentre experience. Injury. 2001;32:761.

Maltese Zuffo B, Lucarelli-Antunes PS, Pivetta LGA, Assef JC. Blunt gastric rupture: a plural clinical presentation and literature review. BMJ Case Rep. 2021;14(6).

Tejerina Alvarez EE, Holanda MS, López-Espadas F, Dominguez MJ, Ots E, Díaz-Regañón J. Gastric rupture from blunt abdominal trauma. Injury. 2004;35:228–31.

Sinicina I, Pankratz H, Buttner A, Mall G. Death due to neurogenic shock following gastric rupture in an anorexia nervosa patient. Forensic Sci Int. 2005;155(1):7–12.

Abdu RA, Garritano D, Culver O. Acute gastric necrosis in anorexia nervosa and bulimia. Two case reports. Arch Surg. 1987;122:830–2.

Saul SH, Dekker A, Watson CG. Acute gastric dilatation with infarction and perforation. Report of fatal outcome in patient with anorexia nervosa. Gut. 1981;22(11):978–83.

Nakao A, Isozaki H, Iwagaki H, Kanagawa T, Takakura N, Tanaka N. Gastric perforation caused by a bulimic attack in an anorexia nervosa patient: report of a case. Surg Today. 2000;30(5):435–7.

Darji P, Gandhi V, Banker H, Chaudhari HD. Spontaneous gastric perforation in 11-year-old boy with anorexia nervosa: rare presentation with right iliac fossa pain (Retraction in: BMJ Case Rep. 2016;2016. pii: bcr2012006529wthd. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2012-006529wthd). BMJ Case Rep. 2012;2012:bcr2012006529. https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2012-006529.

Mishima T, Kohara N, Tajima Y, Maeda J, Inoue K, Ohno T, et al. Gastric rupture with necrosis following acute gastric dilatation: report of a case. Surg Today. 2012;42:997–1000.

Han YJ, Roy S, Siau AMPL, Majid A. Binge-eating and sodium bicarbonate: a potent combination for gastric rupture in adults—two case reports and a review of literature. J Eat Disord. 2022;10:157.

Patiño-Gallegos JA, González-Urquijo M, Padilla-Armendáriz D, Leyva-Alvizo A. Spontaneous rupture of the stomach secondary to bicarbonate ingestion. Rev Gastroenterol Mex (Engl Ed). 2021;86:315–7.

Powell JL, Payne J, Meyer CL, Moncla PR. Gastric necrosis associated with acute gastric dilation and small bowel obstruction. Gynecol Oncol. 2003;90:200–3.

Moslim MA, Mittal J, Falk GA, Ustin JS, Morris-Stiff G. Acute massive gastric dilatation causing ischaemic necrosis and perforation of the stomach. BMJ Case Rep. 2017;2017:bcr2016218513.

England J, Li N. Superior mesenteric artery syndrome: a review of the literature. J Am Coll Emerg Physicians Open. 2021;2: e12454.

Demir MK, Cevher T. A Rare cause and complication of acute gastric dilatation: superior mesenteric artery syndrome and perforation. Eurasian J Med. 2018;50:60–1.

Adson DE, Mitchell JE, Trenkner SW. The superior mesenteric artery syndrome and acute gastric dilatation in eating disorders: a case report of two cases and a review of the literature. Int J Eat Disord. 1997;21:103–14.

Harima H, Kaino S, Sanuki K, Sakaida I. Patient with gastric rupture due to bag ventilation underwent conservative treatment combined with endoscopic observation. BMJ Case Rep. 2021;14: e240116.

Bednarz S, Filipovic M, Schoch O, Mauermann E. Gastric rupture after bag-mask-ventilation. Respir Med Case Rep. 2015;16:1–2.

Chen PN, Shih CK, Li YH, Cheng WC, Hsu HT, Cheng KI. Gastric perforation after accidental esophageal intubation in a patient with deep neck infection. Acta Anaesthesiol Taiwan. 2014;52(2):143–5.

Song JK, Stern WJ, Beaty CD. Gastric perforation: a complication of inadvertent esophageal intubation. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1995;164:1386.

Zhou GJ, Jin P, Jiang SY. Gastric perforation following improper cardiopulmonary resuscitation in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Pak J Med Sci. 2020;36:296–8.

Jalali SM, Emami-Razavi H, Mansouri A. Gastric perforation after cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Am J Emerg Med. 2012;30(2091):e1-2.

Spoormans I, Van Hoorenbeeck K, Balliu L, Jorens PG. Gastric perforation after cardiopulmonary resuscitation: review of the literature. Resuscitation. 2010;81:272–80.

Sahoo MR, Kumar AT, Jaiswal S, Bhujabal SN. Acute dilatation, ischemia, and necrosis of stomach without perforation. Case Rep Surg. 2013;2013.

Rotondo MF, Schwab CW, McGonigal MD, Phillips GR 3rd, Fruchterman TM, Kauder DR, et al. “Damage control”: an approach for improved survival in exsanguinating penetrating abdominal injury. J Trauma. 1993;35:375–82.

Moore EE, Thomas G. Orr Memorial Lecture. Staged laparotomy for the hypothermia, acidosis, and coagulopathy syndrome. Am J Surg. 1996;72:405–10.

Rotondo MF, Zonies DH. The damage control sequence and underlying logic. Surg Clin N Am. 1997;77:761–77.

Moore FA, McKinley BA, Moore EE. The next generation in shock resuscitation. Lancet Lond Engl. 2004;363:1988–96.

Ordoñez CA, Badiel M, Pino LF, Salamea JC, Loaiza JH, Parra MW, et al. Damage control resuscitation: early decision strategies in abdominal gunshot wounds using an easy “ABCD” mnemonic. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012;73:1074–8.

Roberts DJ, Ball CG, Feliciano DV, Moore EE, Ivatury RR, Lucas CE, et al. History of the innovation of damage control for management of trauma patients: 1902–2016. Ann Surg. 2017;265:1034–44.

Khan A, Hsee L, Mathur S, Civil I. Damage-control laparotomy in nontrauma patients: review of indications and outcomes. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2013;75:365–8.

Tartaglia D, Costa G, Camillò A, Castriconi M, Andreano M, Lanza M, et al. Damage control surgery for perforated diverticulitis with diffuse peritonitis: saves lives and reduces ostomy. World J Emerg Surg. 2019;14:19–26.

Girard E, Abba J, Boussat B, Trilling B, Mancini A. Damage control surgery for non-traumatic abdominal emergencies. World J Surg. 2018;42:965–73.

Tamijmarane A, Ahmed I, Bhati CS, Mirza DF, Mayer AD, Buckels JAC, et al. Role of completion pancreatectomy as a damage control option for post-pancreatic surgical complications. Dig Surg. 2006;23:229–34.

Ordoñez CA, Parra M, García A, Rodríguez F, Caicedo Y, Serna JJ, et al. Damage control surgery may be a safe option for severe non-trauma peritonitis management: proposal of a new decision-making algorithm. World J Surg. 2021;45:1043–52.

Banieghbal B, Davies MR. Damage control laparotomy for generalized necrotizing enterocolitis. World J Surg. 2014;28:183–6.

Weber DG, Bendinelli C, Balogh ZJ. Damage control surgery for abdominal emergencies. Br J Surg. 2014;101:e109–18.

William BR, Jason WS. Damage control surgery in emergency general surgery: what you need to know. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2023;95(5):770–9.

Brenner M, Inaba K, Aiolfi A, et al. Resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta and resuscitative thoracotomy in select patients with hemorrhagic shock: early results from the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma’s Aortic Occlusion in Resuscitation for Trauma and Acute Care Surgery Registry. J Am Coll Surg. 2018;226:730–40.

Hoehn MR, Hansraj NZ, Pasley AM, Brenner M, Cox SR, Pasley JD, et al. Resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta for non-traumatic intra-abdominal hemorrhage. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2019;45(4):713–8.

Matsumura Y, Matsumoto J, Idoguchi K, Kondo H, Ishida T, Kon Y, et al. Non-traumatic hemorrhage is controlled with REBOA in acute phase then mortality increases gradually by non-hemorrhagic causes: DIRECT-IABO registry in Japan. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2018;44(4):503–9.

Jansen JO, Hudson J, Cochran C, MacLennan G, Lendrum R, Sadek S, et al. Emergency department resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta in trauma patients with exsanguinating hemorrhage: The UK-REBOA Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2023;330:1862–71.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all included patients and their families, physicians, nurses, paramedics, and all staff members.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HK and KN contributed to the drafting of the manuscript and the study design. TI and AF contributed to the postoperative management of the patient and editing the manuscript. YO and MK critically advised the drafting of the manuscript. All the authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent for publication

Informed consent for publication of the clinical details and images was obtained from patient’s family.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests or personal relationships associated with this manuscript.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Koguchi, H., Nakatsutsumi, K., Ikuta, T. et al. Gastric rupture caused by intragastric perforation of splenic artery aneurysm: a case report and literature review. surg case rep 10, 147 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40792-024-01944-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40792-024-01944-4