Abstract

Background

Calcitonin-producing pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms (PanNENs) are extremely rare. There have been no reports of a patient in whom liver metastases were the presenting finding, and a calcitonin-producing PanNEN was subsequently detected after a lengthy period.

Case presentation

A 53-year-old man had diarrhea for several years. Computed tomography (CT) revealed multiple liver tumors. We performed a left trisectionectomy with a bile duct resection. The histologic examination showed neuroendocrine tumors G1. Immunohistochemistry was positive for calcitonin and the serum calcitonin level was elevated. Neuroendocrine neoplasms of hepatic origin are extremely rare, so a systemic exploration was performed, but no tumor was detected. CT showed a 4-mm calcification in the pancreatic body, but no contrast-enhanced mass was noted. Although the liver tumors were resected, the diarrhea and high serum calcitonin level persisted. Serial examinations were performed for 6 years, but no tumor was identified; however, 6.5 years after the hepatectomy the serum calcitonin level increased. CT showed a 10-mm contrast-enhanced mass in the calcified area of the pancreatic body. A distal pancreatectomy was performed. The histologic examination showed a neuroendocrine tumor G1, which mimicked the liver tumors. Immunohistochemistry was positive for calcitonin. After the distal pancreatectomy, the serum calcitonin level decreased and diarrhea resolved. The calcitonin-producing neuroendocrine neoplasm was considered the pancreatic primary and the hepatic tumors were metastases.

Conclusions

Calcitonin-producing PanNENs may be initially recognized as liver tumors and may become evident after a lengthy period, thus long-term observation is recommended. Aggressive surgeries may contribute to long-term survival.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms (PanNENs) are divided into functional and non-functional [1]. The majority of functional PanNENs are insulinomas followed by gastrinomas, and there are few glucagonomas, somatostatinomas, vasoactive intestinal polypeptide producing tumors, and the others [1]. However, functional calcitonin-producing PanNENs are extremely rare [2, 3].

Among patients with calcitonin-producing PanNENs, approximately 60% have distant metastases at the time of diagnosis, of which liver metastases are the most common [2]. There have been no reports of a patient in whom liver metastases were the presenting finding, and a calcitonin-producing PanNEN was subsequently detected after a lengthy period.

Surgical resection is the cornerstone for calcitonin-producing PanNENs with liver metastases, as in other PanNENs [2, 4]. However, the indication or optimal extent of surgical resection for calcitonin-producing PanNENs with liver metastases remains unclear.

Herein we report a patient with a calcitonin-producing PanNEN who was treated with a distal pancreatectomy a long time after undergoing a left trisectionectomy for liver metastases.

Case presentation

A 53-year-old man was shown to have an elevated serum carcinoembryonic antigen level during a routine physical examination. His medical history was unremarkable, but he had diarrhea for several years. Computed tomography (CT) identified 3 hypervascular tumors in the liver, as follows: segment 1, 12 mm; and segment 4, 18 mm and 28 mm (Fig. 1). A percutaneous transhepatic biopsy of the tumor was performed, and an adenocarcinoma was suspected. We did not perform immunohistochemistry for distinguishing a neuroendocrine neoplasm. We diagnosed liver tumors as intrahepatic cholangiocarcinomas. A tumor of the segment 4 abutted to the right anterior portal vein, left portal vein, and common hepatic duct on CT, so we considered the right anterior and left portal veins resection and a bile duct resection to be necessary. The right posterior portal vein branched independently from the main portal vein, and was distant from the tumors. Moreover, a caudate lobectomy for a tumor of the segment 1 was also needed. Thus, we planned a left trisectionectomy with a bile duct resection. We performed a staging laparoscopy and portal embolization in preparation for a left trisectionectomy. Two weeks later, the remnant liver volume was 47.7% and the future liver remnant plasma clearance rate of indocyanine green was 0.106.

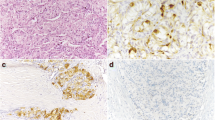

We performed a left trisectionectomy with a bile duct resection. The operative time was 477 min and the blood loss was 1390 ml. He was discharged to home on postoperative day 8 without complications. The formalin-fixed liver specimen had 3 yellow-white masses (Additional file 1: Figure S1). The histologic examination showed neuroendocrine tumors G1 (Fig. 2). Calcification was not observed. There was no lymphatic, vascular, or bile duct invasion. Lymph node metastasis was not observed. Chromogranin-A and synaptophysin were positive. Carcinoembryonic antigen and thyroid transcription factor 1 were weakly positive. Immunohistochemistry was strongly positive for calcitonin, but negative for insulin, gastrin, glucagon, somatostatin, and vasoactive intestinal polypeptide. The serum calcitonin level was elevated (389 pg/ml). Thus, we diagnosed calcitonin-producing neuroendocrine neoplasms of the liver.

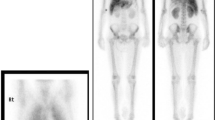

Neuroendocrine neoplasms of hepatic origin are extremely rare, so a systemic exploration was performed. We performed upper and lower endoscopy, a thyroid gland ultrasonography, 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET), and somatostatin receptor scintigraphy, but no tumor was identified. We re-reviewed the preoperative CT, which showed a 4-mm calcification in the pancreatic body, but no contrast-enhanced mass was observed (Fig. 3). There was no evidence of tumor in the calcified area, so we followed the patient closely.

Although the liver tumors were resected, diarrhea persisted and the serum calcitonin also continued to be elevated (Fig. 4). Diarrhea had occurred 3–5 times a day. Repeat ultrasonography, CT, FDG-PET, and somatostatin receptor scintigraphy were performed for 6 years after the hepatectomy, but no obvious tumor was identified; however, 6.5 years after the hepatectomy, laboratory testing revealed elevation of the serum calcitonin level (324 pg/ml). We performed a CT, which showed a 10-mm contrast-enhanced mass in the calcified area of the pancreatic body (Fig. 5). FDG-PET was performed, but showed no significant accumulation. The tumor was suspected to be a PanNEN, thus we performed a distal pancreatectomy. The operative time was 285 min and the blood loss was 509 ml. He was discharged to home on postoperative day 8 without complications. The formalin-fixed pancreatic specimen showed a yellow-white mass that mimicked the liver tumors (Additional file 2: Figure S2). The histologic examination revealed a neuroendocrine tumor G1 that mimicked the liver tumors (Fig. 6). Calcification 4 mm in size was observed. Minimal lymphatic, arterial, and venous invasion was observed, but perineural invasion was not observed. Lymph node metastasis was not observed. Chromogranin-A and synaptophysin were positive. Carcinoembryonic antigen and thyroid transcription factor 1 were also weakly positive. Immunohistochemistry was strongly positive for calcitonin, but negative for insulin, gastrin, glucagon, somatostatin, and vasoactive intestinal polypeptide. After a distal pancreatectomy, the serum calcitonin level decreased and diarrhea resolved. We finally diagnosed him as a calcitonin-producing PanNEN with liver metastases (pathological T1N0M1, stage IV according to the Union for International Cancer Control classification of malignant tumors, 8th edition) [5]. He is currently recurrence-free 6 months after the distal pancreatectomy.

Discussion

Calcitonin-producing PanNENs have been reported to have synchronous liver metastases in approximately 50% of cases, but there are no reports in which liver metastases are the presenting symptom [2, 6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36]. In the present case, however, calcitonin-producing neuroendocrine neoplasms in the liver were evident first, followed by a PanNEN 6.5 years later. A neuroendocrine neoplasm of hepatic origin is extremely rare, while the liver is the most common metastatic site for PanNENs [37,38,39]. In the present case, high serum calcitonin levels and diarrhea persisted after the hepatectomy, but after a distal pancreatomy the serum calcitonin level decreased and diarrhea resolved. These findings suggest that a micro-PanNEN was present in the calcified area in the pancreatic body from the beginning and manifested over a period of 6.5 years. Therefore, it was reasonable to consider that a calcitonin-producing neuroendocrine neoplasm was a pancreatic primary and hepatic tumors were metastases. The present case demonstrated that a calcitonin-producing PanNEN may be initially recognized as a liver tumor that may become evident after a long period of time. Therefore, careful long-term observation is necessary when a calcitonin-producing neuroendocrine neoplasm is observed in the liver.

Although micro-calcifications are often seen in PanNENs, coarse calcifications are extremely rare [3, 40]. The present case revealed that calcitonin-producing PanNENs may show coarse calcifications. Although CT showed a coarse calcification in the pancreatic body, no tumor was detected for a long period of time. Furthermore, FDG-PET and somatostatin receptor scintigraphy showed no accumulation in the coarse calcified area. Therefore, it should be considered that calcitonin-producing PanNENs may be present in coarse calcified areas in the pancreas, even in the absence of findings other than coarse calcifications. It is difficult to decide whether to perform pancreatectomy for the coarse calcified area at the time of hepatectomy, when contrast-enhancing tumors are not apparent because simultaneous hepatectomy and pancreatectomy are high-risk procedures [41]. A watch-and-wait strategy may be acceptable for cases with coarse calcifications but no contrast-enhanced masses in the pancreas.

The main symptom of calcitonin-producing PanNENs is diarrhea, which appears in more than half of patients [2]. Calcitonin is usually secreted by the C cells of the thyroid, but very rarely by PanNENs [2, 25]. Calcitonin reduces serum calcium levels as an antagonist of parathormone, and is also associated with intestinal interactions, inhibiting gastrin and gastric acid secretion and increasing sodium, potassium, chloride, and water secretion, which may explain appearing diarrhea in patients with the high serum calcitonin level [2, 9, 25, 42, 43]. In addition, diarrhea resolves when the serum calcitonin level decrease by resection of calcitonin-producing tumors [2, 44,45,46]. The present case also had suffered from diarrhea for a long time, but diarrhea resolved by resection of a calcitonin-producing PanNEN and decreasing the serum calcitonin level.

Surgical resection is the only curative treatment for calcitonin-producing PanNENs with liver metastases, as with other PanNENs [2, 4]. The present case underwent highly invasive surgeries with a left trisectionectomy, followed by a distal pancreatectomy, both of which had good postoperative outcomes and may have contributed to the long-term prognosis. These favorable outcomes may be attributed to surgeries performed by a board-certified expert surgeon from the Japanese Society of Hepato-Biliary-Pancreatic Surgery [47]. It is considered important that highly advanced surgery should be performed by board-certified expert surgeons.

Conclusions

Calcitonin-producing PanNENs may be initially recognized as liver tumors and may become evident after a long period of time, so careful long-term observation is necessary. If complete resection is possible, aggressive surgeries may contribute to a long-term survival for patients with PanNENs.

Availability of data and materials

The data used for this case report are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Abbreviations

- PanNEN:

-

Pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasm

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- FDG-PET:

-

18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography

References

Ito T, Sasano H, Tanaka M, Osamura RY, Sasaki I, Kimura W, et al. Epidemiological study of gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors in Japan. J Gastroenterol. 2010;45:234–43.

Schneider R, Waldmann J, Swaid Z, Ramaswamy A, Fendrich V, Bartsch DK, et al. Calcitonin-secreting pancreatic endocrine tumors: systematic analysis of a rare tumor entity. Pancreas. 2011;40:213–21.

Uccella S, Blank A, Maragliano R, Sessa F, Perren A, La Rosa S. Calcitonin-producing neuroendocrine neoplasms of the pancreas: clinicopathological study of 25 cases and review of the literature. Endocr Pathol. 2017;28:351–61.

Aoki T, Kubota K, Kiritani S, Arita J, Morizane C, Masui T, et al. Survey of surgical resections for neuroendocrine liver metastases: a project study of the Japan Neuroendocrine Tumor Society (JNETS). J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2021;28:489–97.

James DB, Mary KG, Christian W. International Union Against Cancer (UICC) TNM classification of malignant tumours. 8th ed. New York: Wiley-Liss; 2017.

Rambaud JC, Modigliani R, Matuchansky C, Bloom S, Said S, Pessayre D, et al. Pancreatic cholera. Sudies on tumoral secretions and pathophysiology of diarrhea. Gastroenterology. 1975;69:110–22.

Asa SL, Kovacs K, Killinger DW, Marcon N, Platts M. Pancreatic islet cell carcinoma producing gastrin, ACTH, alpha-endorphin, somatostatin and calcitonin. Am J Gastroenterol. 1980;74:30–5.

Galmiche JP, Chayvialle JA, Dubois PM, David L, Descos F, Paulin C, et al. Calcitonin-producing pancreatic somatostatinoma. Gastroenterology. 1980;78:1577–83.

Gutniak M, Rosenqvist U, Grimelius L, Lundberg JM, Hökfelt T, Rökaeus A, et al. Report on a patient with watery diarrhoea syndrome caused by a pancreatic tumour containing neurotensin, enkephalin and calcitonin. Acta Med Scand. 1980;208:95–100.

Penman E, Lowry PJ, Wass JA, Marks V, Dawson AM, Besser GM, et al. Molecular forms of somatostatin in normal subjects and in patients with pancreatic somatostatinoma. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 1980;12:611–20.

Yamaguchi K, Abe K, Adachi I, Tanaka M, Ueda M, Oka Y, et al. Clinical and hormonal aspects of the watery diarrhea-hypokalemia-achlorhydria (WDHA) syndrome due to vasoactive intestinal polypeptide (VIP)-producing tumor. Endocrinol Jpn. 1980;27(Suppl 1):79–86.

Manche A, Wood SM, Adrian TE, Welbourn RB, Bloom SR. Pancreatic polypeptide and calcitonin secretion from a pancreatic tumour-clinical improvement after hepatic artery embolization. Postgrad Med J. 1983;59:313–4.

Cornish D, Pont A, Minor D, Coombs JL, Bennington J. Metastatic islet cell tumor in von Hippel-Lindau disease. Am J Med. 1984;77:147–50.

Ooi A, Nakanishi I, Kameya T, Funaki Y, Kobayashi K. Calcitonin-producing insulinoma. An immunohistochemical and electron microscopic study. Acta Pathol Jpn. 1986;36:1897–903.

Howard JM, Gohara AF, Cardwell RJ. Malignant islet cell tumor of the pancreas associated with high plasma calcitonin and somatostatin levels. Surgery. 1989;105:227–9.

McLeod MK, Vinik AI. Calcitonin immunoreactivity and hypercalcitoninemia in two patients with sporadic, nonfamilial, gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Surgery. 1992;111:484–8.

Price DE, Absalom SR, Davidson K, Bolia A, Bell PR, Howlett TA. A case of multiple endocrine neoplasia: hyperparathyroidism, insulinoma, GRF-oma, hypercalcitoninaemia and intractable peptic ulceration. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 1992;37:187–8.

Bugalho MJ, Roque L, Sobrinho LG, Hoog A, Nunes JF, Almeida JM, et al. Calcitonin-producing insulinoma: clinical, immunocytochemical and cytogenetical study. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 1994;41:257–60.

Eskens FA, Roelofs EJ, Hermus AR, Verhagen CA. Pancreatic islet cell tumor producing vasoactive intestinal polypeptide and calcitonin. Anticancer Res. 1997;17:4667–70.

Fleury A, Fléjou JF, Sauvanet A, Molas G, Vissuzaine C, Hammel P, et al. Calcitonin-secreting tumors of the pancreas: about six cases. Pancreas. 1998;16:545–50.

Sugimoto F, Sekiya T, Saito M, Iiai T, Suda K, Nozawa A, et al. Calcitonin-producing pancreatic somatostatinoma: report of a case. Surg Today. 1998;28:1279–82.

Takahashi M, Hoshii Y, Kawano H, Setoguchi M, Gondo T, Yamashita Y, et al. Multihormone-producing islet cell tumor of the pancreas associated with somatostatin-immunoreactive amyloid: immunohistochemical and immunoelectron microscopic studies. Am J Surg Pathol. 1998;22:360–7.

Machens A, Haedecke J, Hinze R, Thomusch O, Schneyer U, Dralle H. Hypercalcitoninemia in a sporadic asymptomatic neuroendocrine tumor of the pancreatic tail. Dig Surg. 2000;17:522–4.

Ichimura T, Kondo S, Okushiba S, Morikawa T, Katoh H. A calcitonin and vasoactive intestinal peptide-producing pancreatic endocrine tumor associated with the WDHA syndrome. Int J Gastrointest Cancer. 2003;33:99–102.

Mullerpatan PM, Joshi SR, Shah RC, Tampi CS, Doctor VM, Jagannath P, et al. Calcitonin-secreting tumor of the pancreas. Dig Surg. 2004;21:321–4.

Iacobone M. A calcitonin-secreting tumor of the pancreas. Dig Surg. 2005;22:114.

Jackson C, Buchman AL. Calcitonin-secreting VIPoma. Dig Dis Sci. 2005;50:2203–6.

Delis S, Bakoyiannis A, Giannakou N, Tsigka A, Avgerinos C, Dervenis C. Asymptomatic calcitonin-secreting tumor of the pancreas. A case report. JOP. 2006;7:70–3.

Pusztai P, Sármán B, Illyés G, Székely E, Péter I, Boer K, et al. Hypercalcitoninemia in a patient with a recurrent goitre and insulinoma: a case report. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 2006;114:217–21.

Van den Eynden GG, Neyret A, Fumey G, Rizk-Rabin M, Vermeulen PB, Bouizar Z, et al. PTHrP, calcitonin and calcitriol in a case of severe, protracted and refractory hypercalcemia due to a pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor. Bone. 2007;40:1166–71.

Nasir A, Gardner NM, Strosberg J, Ahmad N, Choi J, Malafa MP, et al. Multimodality management of a polyfunctional pancreatic endocrine carcinoma with markedly elevated serum vasoactive intestinal polypeptide and calcitonin levels. Pancreas. 2008;36:309–13.

Do Cao C, Mekinian A, Ladsous M, Aubert S, D’Herbomez M, Pattou F, et al. Hypercalcitonemia revealing a somatostatinoma. Ann Endocrinol (Paris). 2010;71:553–7.

Schneider R, Heverhagen AE, Moll R, Bartsch DK, Schlosser K. Differentiation between thyroidal and ectopic calcitonin secretion in patients with coincidental thyroid nodules and pancreatic tumors—a report of two cases. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 2010;118:520–3.

Kon T, Wada R, Suzuki R, Nakayama Y, Ebina Y, Yagihashi S. VIP and calcitonin-producing pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor with watery diarrhea: clinicopathological features and the effect of somatostatin analogue. JOP. 2012;13:226–30.

Kováčová M, Filková M, Potočárová M, Kiňová S, Pajvani UB. Calcitonin-secreting pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors: a case report and review of the literature. Endocr Pract. 2014;20:e140–4.

Giannetta E, Gianfrilli D, Pozza C, Lauretta R, Graziadio C, Sbardella E, et al. Extrathyroidal calcitonin secreting tumors: pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors in patients with multinodular goiter: two case reports. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95: e2419.

Boyar Cetinkaya R, Aagnes B, Thiis-Evensen E, Tretli S, Bergestuen DS, Hansen S. Trends in incidence of neuroendocrine neoplasms in Norway: a report of 16,075 cases from 1993 through 2010. Neuroendocrinology. 2017;104:1–10.

Spolverato G, Bagante F, Aldrighetti L, Poultsides GA, Bauer TW, Fields RC, et al. Management and outcomes of patients with recurrent neuroendocrine liver metastasis after curative surgery: an international multi-institutional analysis. J Surg Oncol. 2017;116:298–306.

Zhang XF, Beal EW, Weiss M, Aldrighetti L, Poultsides GA, Bauer TW, et al. Timing of disease occurrence and hepatic resection on long-term outcome of patients with neuroendocrine liver metastasis. J Surg Oncol. 2018;117:171–81.

Buetow PC, Parrino TV, Buck JL, Pantongrag-Brown L, Ros PR, Dachman AH, et al. Islet cell tumors of the pancreas: pathologic-imaging correlation among size, necrosis and cysts, calcification, malignant behavior, and functional status. Am J Roentgenol. 1995;165:1175–9.

Endo I, Hirahara N, Miyata H, Yamamoto H, Matsuyama R, Kumamoto T, et al. Mortality, morbidity, and failure to rescue in hepatopancreatoduodenectomy: an analysis of patients registered in the National Clinical Database in Japan. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2021;28:305–16.

Oberg K, Lööf L, Boström H, Grimelius L, Fahrenkrug J, Lundqvist G. Hypersecretion of calcitonin in patients with the Verner-Morrison syndrome. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1981;16:135–44.

Neer EJ. Heterotrimeric G proteins: organizers of transmembrane signals. Cell. 1995;80:249–57.

Bernier JJ, Rambaud JC, Cattan D, Prost A. Diarrhoea associated with medullary carcinoma of the thyroid. Gut. 1969;10:980–5.

Steinfeld CM, Moertel CG, Woolner LB. Diarrhea and medullary carcinoma of the thyroid. Cancer. 1973;31:1237–9.

Saad MF, Ordonez NG, Rashid RK, Guido JJ, Hill CS Jr, Hickey RC, et al. Medullary carcinoma of the thyroid. A study of the clinical features and prognostic factors in 161 patients. Medicine (Baltimore). 1984;63:319–42.

Otsubo T, Kobayashi S, Sano K, Misawa T, Katagiri S, Nakayama H, et al. A nationwide certification system to increase the safety of highly advanced hepatobiliary-pancreatic surgery. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhbp.1186.

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the concept of this case report. RYm drafted the manuscript. RYg performed the surgery and conducted postoperative management. KY, MA, YT, AT, and KK supervised the writing of the report. All authors participated in interpreting the results and writing the report. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Our institutional ethics committee approved the publication of this case report (Approval No. 2022-12).

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and the accompanying images.

Competing interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Figure S1.

Gross appearance of the liver shows yellow-white masses in segment 1 (A) and segment 4 (B, C). MHV, middle hepatic vein; LPV, left portal vein; RAPV, right anterior portal vein; CHD, common hepatic duct.

Additional file 2: Figure S2.

Gross appearance of the pancreas shows a yellow-white mass similar to the liver tumors.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yamamoto, R., Yamaguchi, R., Yoshida, K. et al. A calcitonin-producing pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasm treated with distal pancreatectomy a lengthy time after a left trisectionectomy for liver metastases: a case report. surg case rep 8, 217 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40792-022-01575-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40792-022-01575-7