Abstract

Background

Falciform ligament abscess (FLA) is a rare disease, and its diagnosis can be challenging without typical image findings of an abscess. We report a patient with FLA that presented as a mass, with an indistinct border between it and the liver, in addition to disseminated foci within the liver. This made it difficult to determine whether it was FLA or a malignancy.

Case presentation

A 69-year-old man presented with epigastric pain. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography revealed a 25-mm mass below the middle of the diaphragm. Based on an initial diagnosis of infection of the falciform ligament, we administered conservative antibiotic treatment and there was initial improvement in the patient’s clinical condition and laboratory data. However, he continued to experience mild epigastric pain. A month later, imaging studies revealed enlargement of the falciform ligament mass and the emergence of a new nodule in the liver, whereas laboratory findings showed re-elevated C-reactive protein levels. Since conservative treatment had failed, we decided to perform surgery. Considering the imaging study findings, malignant disease could not be ruled out. Based on the operative findings, we performed combined resection of the falciform ligament, left liver, and gallbladder. Histopathological examination of the resected specimens revealed extensive neutrophil infiltration and the presence of giant cells and foam cells within the lesions. These findings were indicative of abscess. Pseudomonas aeruginosa was cultured from the pus in the falciform ligament mass and bile in the gallbladder. Although multiple abscesses postoperatively developed in the residual portion of the liver, they could be treated through antibiotic therapy.

Conclusions

FLA can spread to both adjacent and distant organs via its rich vascular and lymphatic networks. When FLA displays atypical image findings and/or an atypical clinical course, it can be difficult to distinguish it from malignant disease. In such cases, surgical treatment, with intraoperative pathological diagnosis, should be attempted.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Background

The falciform ligament is strongly connected to surrounding organs via rich vascular and lymphatic networks. Falciform ligament abscess (FLA) is a rare disease, typically caused by the transmission of bacteria from other organs via these networks. Diagnosis is relatively simple in cases with typical image findings, because an abscess usually presents on computed tomography (CT) scans or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) as a mass with well-defined enhanced capsule wall and with internal fluid and air content. However, when an abscess has minimal fluid, it can be difficult to distinguish from a malignant tumor.

Since FLA results from bacteria transmitted to the falciform ligament from surrounding organs, it could also spread bacteria to surrounding or distant organs via the same vascular or lymphatic pathways. However, instances of this have not been reported.

Here, we report a patient with FLA that presented as a mass with disseminated foci in the liver and a border indistinct from the liver. These characteristics made the FLA difficult to differentiate from malignancy. This is the first report of FLA with disseminated intrahepatic foci.

Case presentation

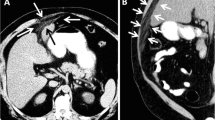

A 69-year-old man with no significant medical history presented to the emergency department with epigastric pain that had lasted for 5 days. On physical examination, he had a slight fever and mild tenderness around the epigastrium. Laboratory findings were unremarkable, except for mildly elevated C-reactive protein (CRP) levels of 6.9 mg/dl. Contrast-enhanced CT revealed a 25-mm enhanced mass with small low-density areas below the middle of the diaphragm (Fig. 1). On MRI, the signal intensity of the mass was high in diffusion-weighted images, and small high-intensity areas inside the mass were seen on T2-weighted images (Fig. 2).

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the falciform ligament abscess at the time of the first admission. a The falciform ligament mass showed high signal intensity on diffusion-weighted images (white arrow). b Small high-intensity areas within the mass were visible on T2-weighted images (white arrowhead)

Based on a diagnosis of falciform ligament infection, we administered conservative therapy in the form of sulbactam/ampicillin (SBT/ABPC) infusion and subsequent oral clavulanic acid/amoxicillin (CVA/AMPC). Performed at admission, the blood culture was negative. Imaging studies showed no apparent pancreatobiliary or other organ infections. The patient also had no biliary history. Additionally, the upper and lower gastrointestinal endoscopies revealed no significant findings. Therefore, the cause of FLA was unclear. The patient’s general condition and laboratory data improved, and he was discharged. However, he continued to complain of mild epigastric pain. A further CT scan was performed a month after discharge, and this revealed that the falciform ligament mass had increased in size. We also observed an obscure border between the mass and the liver and a new low-density nodule in liver segment three, with upstream bile duct dilatation (Fig. 3). After second CT, the patient was readmitted due to increased abdominal pain and re-elevation of his CRP levels. Since conservative treatment had failed, we decided to perform surgery. Although tests for tumor markers were negative, considering the changes to imaging study findings, malignant disease could not be ruled out. Figure 4 shows the clinical course of the patient after the first admission till the operation.

The clinical course of the patient after the first admission till the operation. ALT alanine aminotransferase, ALP alkaline phosphatase, AST aspartate aminotransferase, CRP C-reactive protein, CT computed tomography, CVA/AMPC clavulanic acid/amoxicillin, GGT gamma-glutamyltransferase, SBT/ABPC sulbactam/ampicillin, WBC white blood cell

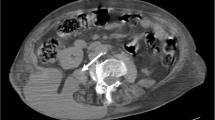

During surgery, laparotomy and intraoperative ultrasonography confirmed our imaging findings, revealing an indistinct border between the mass of the falciform ligament and the liver, and a yellowish-white nodule in liver segment three (Fig. 5). We found no adhesion around the gallbladder and no gallbladder wall thickening. Additionally, the bile juice in the gallbladder, collected intraoperatively, was normal in color and odorless. Based on these findings, considering the possibility of malignancy, we decided to perform left hepatectomy and cholecystectomy.

The cut surfaces of the resected specimens showed both the falciform ligament mass and the liver segment three nodule to be pale white, irregularly shaped nodular lesions. Histopathological examination revealed extensive neutrophil infiltration and the presence of giant cells and foam cells in both lesions, consistent with abscesses (Fig. 6). Pseudomonas aeruginosa was cultured from the pus in the falciform ligament mass and the bile in the gallbladder. Although multiple abscesses developed postoperatively in the remaining liver, they rapidly improved with the use of antibiotics (levofloxacin) and the patient was discharged. He did not experience subsequent recurrence of intra-abdominal abscesses.

Histopathological examination of the resected specimens. a Gross findings showed the falciform ligament mass and the yellowish-white nodule in liver segment three (white arrows). b Microscopic examination revealed numerous neutrophils, giant cells (yellow arrowhead), and foam cells (white arrowhead)

Discussion

FLA is a rare condition, with only about 20 adult cases reported in the literature so far, including reports of ligamentum teres abscess. Table 1 shows the results of a Pub-Med database search using the terms “falciform ligament”, “ligamentum teres”, “round ligament”, “abscess”, and “gangrene”. FLA is typically caused by bacterial transmission from infected surrounding organs to the falciform ligament via their rich vascular or lymphatic networks. Although FLA would also be expected to spread infection to other organs through these networks in the same manner, there have been no reports of this in the academic literature. This is the first report of a case of FLA with disseminated intrahepatic foci.

The vascular and lymphatic networks that incorporate the falciform ligament connect it to the liver, diaphragm, retroperitoneum, mediastinum, abdominal wall, and chest wall. Its arterial blood flow is supplied by the left inferior phrenic artery, the middle hepatic artery, and, to a lesser extent, the left and right hepatic arteries [22,23,24]. These have anastomoses with terminal branches of the internal thoracic artery [25]. The veins of the falciform ligament are known as the vein of Sappey and vein of Burow. These drain into the left inferior phrenic vein and liver parenchyma (or peripheral portal veins), and communicate with the intrathoracic vein and epigastric vein [24,25,26]. The superficial lymphatics of the liver drain lymph along the falciform ligament and both down toward the abdominal wall and up to the parasternal lymph nodes [27]. Because of the presence of these vascular networks, FLA is believed to be caused by the transmission of bacteria from surrounding structures. In pediatric cases, omphalitis (infection of the umbilicus) is thought to be the causative primary disease that passes the infection to the falciform ligament, resulting in FLA [28]. However, many of the case reports of adult cases trace FLA back to primary hepatobiliary infections (Table 1). In the patient discussed herein, there were no obvious signs of cholecystitis or cholangitis through imaging studies. However, as Pseudomonas aeruginosa was detected both in the bile of the gallbladder and the abscess of the falciform ligament, bile infection likely triggered the development of the disease. Regarding the disseminated intrahepatic foci, continuous thickening of Glissonian tissue from the abscess to the disseminated foci in the liver was observed in the resected specimen, suggesting that bacteria traveled into the liver via vessels in the Glissonian tissue.

Although FLA is rare, diagnosis is relatively easy in cases with typical image findings as an abscess usually has a well-defined enhanced capsule wall and internal fluid and air content. In this case, small cystic lesions within the falciform ligament mass suggested the possibility of an abscess. Because antimicrobial agents were initially effective, we first diagnosed the mass as an infection of the falciform ligament. However, enlargement of the mass and a new nodule in the liver on CT images after initial treatment implied a malignant tumor. Tumors of the falciform ligament are uncommon; nonetheless, a metastatic case of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma in the falciform ligament with similar imaging findings to our case has been reported [29].

While conservative management with puncture or drainage is reported to be effective for FLA, many recommend surgical treatment. In our case, conservative treatment was only able to provide temporary relief from the disease and it soon recurred, leading to eventual surgical treatment. Conservative treatment for abscesses often requires prolonged antibiotic therapy. Relapse may occur during or after conservative treatment due to bacterial replacement or inadequate treatment. In our case, Pseudomonas aeruginosa was detected in the resected specimen and this is naturally resistant to the SBT/ABPC and CVA/AMPC used for effective initial treatment. Guidelines for the treatment of intra-abdominal abscesses emphasize the importance of source control [30]. The abscess in our case presented as a mass rather than capsulized fluid. Therefore, puncture or drainage would have been ineffective as methods of source control. Although multiple liver abscesses developed after surgery in our case, these quickly improved after the administration of antibiotics (levofloxacin). This demonstrates the importance of source control therapy for the treatment of FLA. As for the operative procedures, although simple resection of the falciform ligament, with or without cholecystectomy, depending on the presence of cholecystitis, has been performed in many reported cases, we performed resection with hepatectomy due to the possibility of cancer, based on the operative findings. In such instances, there should be an intraoperative pathological examination of frozen sections before determining the final procedure. If intraoperative pathological examination of the liver nodule had been performed first in the case presented here, left hepatectomy could have been avoided.

Conclusions

We have here reported a case of FLA with a mass-like appearance and disseminated intrahepatic foci. It should be recognized that FLA can spread to both near and distant organs via its rich vascular and lymphatic networks.

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing does not apply to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed in the current study.

Abbreviations

- CRP:

-

C-reactive protein

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- CVA/AMPC:

-

Clavulanic acid/amoxicillin

- FLA:

-

Falciform ligament abscess

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- SBT/ABPC:

-

Sulbactam/ampicillin

References

Hennessey JD. Abscess in the falciform ligament. J Ir Med Assoc. 1956;38(228):176.

Charuzi I, Freund H. Gangrene of the hepatic round ligament causing diffuse peritonitis: a case report. Am Surg. 1976;42(12):925–6.

Doscher W, Chardavoyne R, Teicher I. Abscess of falciform ligament. N Y State J Med. 1980;80(7):1131–3.

Sones PJ Jr, Thomas BM, Masand PP. Falciform ligament abscess: appearance on computed tomography and sonography. Am J Roentgenol. 1981;137(1):161–2.

Watson SD, McComas B, Rannick GA, Stanton PE Jr. Gangrenous ligamentum teres hepatis causing acute abdominal symptoms. South Med J. 1988;81(2):267–9.

Migliaccio AV. Disease of round ligament of the liver simulating acute gall bladder. Cases presenting as acute surgical emergencies not previously reported. R I Med J. 1988;71(6):239–42.

Mori H, Aikawa H, Hirao K, Futagawa S, Fukuda T, Maeda H, et al. Exophytic spread of hepatobiliary disease via perihepatic ligaments: demonstration with CT and US. Radiology. 1989;172(1):41–6.

Brock JS, Pachter HL, Schreiber J, Hofstetter SR. Surgical diseases of the falciform ligament. Am J Gastroenterol. 1992;87(6):757–8.

Ko SF, Chen YS, Ng SH, Lee TY, Chen WJ, Cheng YF. Mucin-hypersecreting papillary cholangiocarcinoma presenting as abdominal wall abscess: CT and spiral CT cholangiography. Abdom Imaging. 1996;21(3):222–5.

Losanoff JE, Kjossev KT. Isolated gangrene of the round and falciform liver ligaments: a rare cause of peritonitis: case report and review of the world literature. Am Surg. 2002;68(9):751–5.

de Melo VA, de Melo GB, Silva RL, Aragão JF, Rosa JE. Falciform ligament abscess: report of a case. Rev Hosp Clin Fac Med Sao Paulo. 2003;58(1):37–8.

Martin TG. Videolaparoscopic treatment for isolated necrosis and abscess of the round ligament of the liver. Surg Endosc. 2004;18(9):1395.

Tsukuda K, Furutani S, Nakahara S, Tada A, Watanabe K, Takagi S, et al. Abscess formation of the round ligament of the liver: report of a case. Acta Med Okayama. 2008;62(6):411–3.

Arakura N, Ozaki Y, Yamazaki S, Ueda K, Maruyama M, Chou Y, et al. Abscess of the round ligament of the liver associated with acute obstructive cholangitis and septic thrombosis. Intern Med. 2009;48(21):1885–8.

Czymek R, Bouchard R, Hollmann S, Kagel C, Frank A, Bruch HP, et al. First complete laparoscopic resection of a gangrenous falciform ligament. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;22(1):109–11.

Warren LR, Chandrasegaram MD, Madigan DJ, Dolan PM, Neo EL, Worthley CS. Falciform ligament abscess from left-sided portal pyaemia following malignant obstructive cholangitis. World J Surg Oncol. 2012;22(10):278.

Atif QA, Khaliq T. Postpancreatitis abscess of falciform ligament: an unusual presentation. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2015;25(11):837–8.

Sen D, Arora V, Sohal RS, Hari PS. The “sausage” abscess: Abscess of the liagamentum teres hepatis. BJR Case Rep. 2016;2:20150139.

Fujikawa H, Araki M. Hepatobiliary and pancreatic abscess of the ligamentum teres hepatis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;35(4):529.

Bhattacharya K, Reddy P, Bhutia PD. Abscess of the ligamentum teres: a rare entity. Indian J Surg. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12262021030530.

Fang Y, Huang H. Abscess of ligamentum teres hepatis: a case report. Asian J Surg. 2021;44(10):1297–9.

Williams DM, Cho KJ, Ensminger WD, Ziessman HA, Gyves JW. Hepatic falciform artery: anatomy, angiographic appearance, and clinical significance. Radiology. 1985;156(2):339–40.

Ibukuro K, Tsukiyama T, Mori K, Inoue Y. Hepatic falciform ligament artery: angiographic anatomy and clinical importance. Surg Radiol Anat. 1998;20(5):367–71.

Li XP, Xu DC, Tan HY, Li CL. Anatomical study on the morphology and blood supply of the falciform ligament and its clinical significance. Surg Radiol Anat. 2004;26(2):106–9.

Ibukuro K, Fukuda H, Tobe K, Akita K, Takeguchi T. The vascular anatomy of the ligaments of the liver: gross anatomy, imaging and clinical applications. Br J Radiol. 2016;89(1064):20150925.

Yoshimitsu K, Honda H, Kuroiwa T, Irie H, Aibe H, Shinozaki K, et al. Unusual hemodynamics and pseudolesions of the noncirrhotic liver at CT. Radiographics. 2001;21:S81-96.

Pupulim LF, Vilgrain V, Ronot M, Becker CD, Breguet R, Terraz S. Hepatic lymphatics: anatomy and related diseases. Abdom Imaging. 2015;40(6):1997–2011.

Lipinski JK, Vega JM, Cywes S, Cremin BJ. Falciform ligament abscess in the infant. J Pediatr Surg. 1985;20(5):556–8.

Nomura Y, Sakai H, Akiba J, Hisaka T, Sato T, Goto Y, Akashi M, et al. Laparoscopic left hepatectomy for a patient with intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma metastasis in the falciform ligament: a case report. BMC Surg. 2021;21(1):122.

Mazuski JE, Tessier JM, May AK, Sawyer RG, Nadler EP, Rosengart MR, et al. The surgical infection society revised guidelines on the management of intra-abdominal infection. Surg Infect. 2017;18(1):1–76.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Enago (www.enago.jp) for the English language editing.

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

TK authored the paper and contributed to the creation of the figures and table. TK performed the surgery and perioperative patient management. IS and TI served as surgical assistants. IS performed initial conservative treatment. HI conducted the pathological examination. The remaining coauthors contributed to the perioperative management of the patient. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

The patient provided written informed consent to publication. As no experiment was conducted, no consent to participation was required.

Competing interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kuribara, T., Shigeyoshi, I., Ichikawa, T. et al. Falciform ligament abscess with disseminated intrahepatic foci: a case report. surg case rep 8, 112 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40792-022-01466-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40792-022-01466-x