Abstract

Background

Internal hernias are formed by the protrusion of internal organs through an aperture formed congenitally or postoperatively. Internal hernias are most commonly associated with the small intestine. Only two cases of a post-sigmoid colostomy internal hernia of the stomach have been reported. This hernia arises from the space between the lifted sigmoid colon and the left abdominal wall. In the two aforementioned cases, treatment comprised suturing of the sigmoid colon to the lateral abdominal wall and changing of the intraperitoneal route to an extraperitoneal one. Herein, we present a very rare case who underwent laparoscopic gastropexy for a post-sigmoid colostomy internal hernia of the stomach.

Case presentation

Our patient, a 67-year-old woman, was undergoing chemoradiation for rectal cancer and planned to undergo abdominoperineal resection. However, tumor perforation resulted in a high fever and a right gluteal abscess; therefore, a sigmoid colostomy was performed through the intraperitoneal route in the left lower abdomen. One month after the surgery, the patient presented to our emergency room with vomiting, abdominal pain, and abdominal distension. Computed tomography revealed a markedly distended stomach caused by the obstruction of the pylorus secondary to the colostomy; laparoscopic gastropexy was performed subsequently and the postoperative course was uneventful.

Conclusions

This is the first report on the laparoscopic gastropexy treatment of a post-sigmoid colostomy internal hernia of the stomach; our findings may help physicians manage such hernias.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

An internal hernia is a protrusion of the internal organs through an aperture formed congenitally or postoperatively [1]. Internal hernias are most commonly associated with the small intestine and are rarely associated with the stomach. Internal hernias of the stomach comprise parastomal hernias [2] and post-colostomy internal hernias [3, 4]. The stomach dilates after eating and descends into the pelvis through the space between the lifted sigmoid colon and the left abdominal wall. Therefore, the antrum is obstructed by the sigmoid colon, resulting in the internal hernia (Fig. 1).

The stomach dilates after eating and descends into the pelvis through the space between the lifted sigmoid colon and the lateral abdominal wall. The antrum is obstructed by the lifted sigmoid colon, resulting in the internal hernia of the stomach. A dotted line and a double circle indicate the stomach and the sigmoid colostomy, respectively

Notably, only two cases of post-colostomy internal hernias have been reported. The first case was treated by suturing the sigmoid colon to the lateral abdominal wall [3], while the second case was treated by changing the intraperitoneal route to an extraperitoneal one [4]. Both treatments are for closing an aperture, and the use of gastropexy for treatment has not been reported yet.

Herein, we present a very rare case of a 67-year-old patient who underwent laparoscopic gastropexy [5] for an internal hernia of the stomach that developed after a sigmoid colostomy.

Case presentation

A 67-year-old woman was undergoing chemoradiation therapy for lower rectal cancer which arose from the right side of the anal canal and invaded the anal sphincter muscle. She was scheduled to undergo a laparoscopic or robot-assisted abdominoperineal resection. However, tumor perforation resulted in a high fever and a right gluteal abscess; therefore, a sigmoid colostomy was performed through the intraperitoneal route in the left lower abdomen.

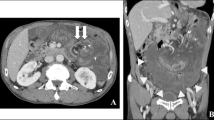

One month after the surgery, the patient presented to our emergency room with vomiting, abdominal pain, and abdominal distension. Computed tomography (CT) revealed marked dilation of the stomach due to the obstruction of the pylorus caused by the sigmoid colostomy (Fig. 2). After insertion of a nasogastric tube and drainage of approximately 2000 mL of gastric juice, the abdominal symptoms improved rapidly. Because laparoscopic abdominoperineal resection was scheduled for 2 months later and preoperative gastroscopy showed no lesions that could cause stenosis, we decided to observe her without surgery. However, she developed an recurrent internal hernia twice; thus, we performed a laparoscopic gastropexy [6] for the internal hernia of the stomach.

We inserted trocars of 12 mm, 5 mm, and 5 mm into the right lower abdomen, right lateral abdomen, and mid-lower abdomen, respectively (Fig. 3). The endoscope was inserted into the stomach, and air was passed through it. Two points of the gastric antrum were fixed to the abdominal wall using a Funada-style loop gastropexy device [7] and gastroscopy (Figs. 3 and 4); thereafter, more air was pumped into the stomach. However, the internal hernia did not relapse, and we completed the operation. The amount of blood loss was small, and the operation time was 1 h and 4 min. The postoperative course was uneventful. She started eating the next day and was discharged on postoperative day 5. The internal hernia did not recur until the next surgery. Contrast enhanced CT showed that the pylorus was on the right side of the lifted sigmoid colon (Fig. 5).

A laparoscopic abdominoperineal resection was performed approximately 2 months after the laparoscopic gastropexy. Although it was converted to laparotomy due to the presence of adhesions, the sutures between the stomach and the peritoneum could be removed easily. The internal hernia was treated by suturing the sigmoid colon to the lateral abdominal wall. The postoperative course was good and the internal hernia of the stomach did not recur.

Discussion

Most postoperative internal hernias are caused by mesenteric defects created by gastrointestinal and colorectal surgeries [8]. Mesenteric defects often lead to intestinal obstruction and rarely to internal hernias of the stomach. Two cases of internal hernias of the stomach following a sigmoid colostomy have been reported; one was treated by suturing the sigmoid stoma to the abdominal wall [3], while the other was treated by changing the intraperitoneal route to an extraperitoneal one [4]. In both cases, an abdominoperineal resection was performed and an end stoma was created. Contrastingly, in the present case, a colostomy with double orifices was created after rectal perforation.

Gastropexy was originally performed for gastric volvulus [9]. Currently, it is often performed laparoscopically [5]. The site and number of the sutures have not been standardized, however, previous reports revealed that laparoscopic gastropexy had good postoperative results [5, 6] and it was adopted in the present case. We have described the case of a 67-year-old patient who underwent laparoscopic gastropexy for an internal hernia of the stomach after sigmoid colostomy.

Two previous cases reported that a reliable treatment for hernia was to close the aperture surgically [3, 4]. It was thought best to perform abdominoperineal resection and the aperture closure surgery at the same time, however, since the patient was undergoing chemoradiation therapy and it was difficult to change the date of lengthy surgery, we decided to perform them separately. The next operation was planned to be either laparoscopic or robotic, and the right buttock was partially resected to prevent local recurrence due to rectal perforation. The right rectus abdominis muscle could be used as a reconstructive organ for the defect. However, in robot-assisted surgery, the trocars must be inserted at or near the muscle; therefore, to avoid muscle damage, we chose laparoscopic surgery (Fig. 6).

Laparoscopic suturing of the lifted sigmoid colon to the lateral abdominal wall was complicated and could prevent the movement of the assistant’s forceps during the next operation (Fig. 7). Changing the intraperitoneal route to an extraperitoneal one was also considered complicated and required cutting the anal side of the stoma. We performed a simple suture fixation of the stomach to the anterior abdominal wall, because the procedure was easy, short, and comprised only two suture fixations. Moreover, the sutures could be removed easily.

Suturing of the lifted sigmoid colon to the lateral abdominal wall could prevent the movement of the assistant’s forceps from the fifth trocar during the next operation. The dotted line, a black arrow and numbers point to the sigmoid mesentery, direction of forceps and order of port insertion, respectively

In the present case, laparoscopic gastropexy was performed using a Funada-style loop gastropexy device during gastroscopy because we thought that suturing was difficult due to the proximity between the port insertion site and the suture site (Fig. 3). Inflating the stomach during gastroscopy helped confirm an adequate resolution of the hernia and rule out a recurrence. Considering that the preoperative gastroscopy showed gastroptosis, the procedure was considered appropriate.

Because the stomach must be fixed to the right lower abdomen, the location of the right inferior epigastric artery must be confirmed to avoid injuries. Additionally, two fixation points may cause new internal hernias. In the present case, two-point fixation did not cause new internal hernias. Two-point fixation was chosen because one-point fixation could cause stomach volvulus [6]. We believe that laparoscopic gastropexy for internal hernias of the stomach is a good alternative for patients who require additional surgery.

Laparoscopic gastropexy, though simple and minimally invasive, is an incomplete procedure. The most reliable treatment for hernia is to close the aperture surgically. In the present case, we performed laparoscopic gastropexy as the subsequent surgery, and the patient recovered without recurrence. Because this report only details one case, further studies are needed with more cases in the future.

Conclusions

To our knowledge, this is the first report on the performance of laparoscopic gastropexy in the management of an internal hernia of the stomach after a colostomy. Our observations suggest that laparoscopic gastropexy may be useful for such hernias.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

References

Martin LC, Merkle EM, Thompson WM. Review of internal hernias: radiographic and clinical findings. Am J Roentgenol. 2006;186:703–17.

Barber-Millet S, Pous S, Navarro V, Iserte J, García-Granero E. Parastomal hernia containing stomach. Int Surg. 2014;99:404–6.

Hashida H, Kita R, Kondo M, Mizuno R, Kobayashi H, Kaihara S. Internal hernia of the stomach associated with colostomy after laparoscopic surgery for rectal cancer: a case report. Surg Case Rep. 2020;6:4–7.

Shinohara K, Suzuki M, Asaba Y, Maeta T, Ishida T, Mizukami Y. Internal hernia of the stomach through the lateral space of the colostomy: a case report. J Surg Case Rep. 2020;2020:1–3.

Siu WT, Leong HT, Li MKW. Laparoscopic gastropexy for chronic gastric volvulus. Surg Endosc. 1998;12:1356–7.

Takahashi T, Yamoto M, Nomura A, Ooyama K, Sekioka A, Yamada Y, et al. Single-incision laparoscopic gastropexy for mesentero-axial gastric volvulus. Surg Case Reports. 2019;5:0–3

Funada M. Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy: a new gastropexy method. Gastrointest Endosc. 1991;33:2681.

Toh JWT, Lim R, Keshava A, Rickard M. The risk of internal hernia or volvulus after laparoscopic colorectal surgery: a systematic review. Color Dis. 2016;18:1133–41.

Tanner NC. Chronic and recurrent volvulus of the stomach. Am J Surg. 1968;115:505–15.

Acknowledgements

We thank Editage (www.editage.com) for English language editing.

Funding

No funding was received for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YT wrote the draft. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethics approval was obtained from the Ethical Review Board for Clinical Studies at Tottori Prefectural Central Hospital.

Consent for publication

Informed consent for the publication of this report and any accompanying images was obtained from the patient and her family.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tada, Y., Orihara, J., Wada, Y. et al. Post-colostomy internal hernia of the stomach treated with laparoscopic gastropexy: a case report. surg case rep 8, 105 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40792-022-01455-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40792-022-01455-0