Abstract

Background

Arteriovenous malformation (AVM) of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract can cause bleeding. The treatment choice for GI tract AVM is surgical resection of the involved bowel segment with complete resection of the nidus. The AVM formed in the duodenum or pancreatic head could also cause gastrointestinal bleeding, and there are several reports of pancreaticoduodenectomy as its treatment. However, if the area of AVM can be accurately identified during surgery, it may be possible to completely resect the AVM while preserving the organ. We report a case of duodenal AVM in a patient successfully treated with a subtotal stomach-preserving duodenal bulb resection using intraoperative indocyanine green (ICG) angiography technique.

Case presentation

An 18-year-old man was diagnosed with duodenal AVM after several examinations for anemia and was referred to our hospital for further treatment. Preoperative imaging studies showed that the inflow vessels of this duodenal AVM were the inferior pyloric artery and the superior duodenal artery, and the AVM was localized to the duodenal bulb. Thereafter, stomach-preserving duodenal bulb resection preceded by ligation of the inflow vessels was performed. During the surgery, ICG angiography clearly demonstrated the area, where the nidus was distributed, and a duodenal bulb resection with complete resection of the AVM was successfully performed. There was no recurrence at the 6-month follow-up.

Conclusions

Intraoperative ICG angiography was a useful procedure for precise identification of the AVM of the GI tract.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Gastrointestinal (GI) arteriovenous malformation (AVM) sometimes causes GI bleeding [1, 2], and the radical treatment for AVM is complete surgical removal of the nidus lesion. It is important to accurately identify the lesion and resect the appropriate area, because resection with sufficient margins is overly invasive, and resection with insufficient margins leads to disease recurrence. Herein, we report a duodenal AVM case in which we determined the optimal surgical margins using intraoperative indocyanine green (ICG) angiography.

Case presentation

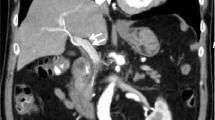

An 18-year-old man visited the previous hospital with a chief complaint of black stool and lightheadedness. He had a past medical history of surgery for a congenital skin tag on his buttock when he was 5 years and was noted to have congenital dysplasia of the sacrum. When he visited the hospital, severe anemia (hemoglobin level, 5.6 g/dL) was identified. Upper and lower endoscopy revealed erosions of the duodenal mucosa, and capsule endoscopy revealed a small amount of bleeding in the duodenum bulb. Finally, the angiography revealed duodenal AVM. There were no other lesions in the GI tract that could cause bleeding or anemia, and it was considered that a small amount of continuous bleeding from the duodenal AVM was the cause of the anemia. Thereafter, he was transferred to our hospital for further examination and treatment. Upper GI endoscopy revealed mucosal color changes in the duodenal bulb (Fig. 1). Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) revealed a hyper-enhancing duodenal bulb wall, but no other enhancing lesions suspected as AVMs were detected in other areas of the body. Angio-CT findings suggested that the inflow vessel was the inferior pyloric artery (IPA) and superior duodenal artery (SDA), which branches off from the gastroduodenal artery (Fig. 2).

Preoperative contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CECT) and angio-CT images. a–c CECT images showing a hyper-enhancing duodenal bulb wall (arrowhead). No nidus is found in the pancreatic head. (a cross section, b sagittal section, c coronal section). d Angiography shows the arteries flowing into the duodenal AVM [arrow: inferior pyloric artery (IPA), arrowhead: superior duodenal artery (SDA)]. e Angio-CT images also show that the inferior pyloric artery (IPA) and superior duodenal artery (SDA) branching off from the gastroduodenal artery (GDA) are the inflow vessels. (arrow: GDA; arrowhead: IPA and SDA)

Based on these findings, a subtotal stomach-preserving duodenal bulb resection preceded by IPA and SDA ligation to reduce bleeding during surgery was planned. In addition, intraoperative ICG angiography was planned to determine the final resection line. We prepared to perform pancreas-sparing duodenectomy if the resection line of the duodenum indicated by ICG angiography was anorectal to the duodenal minor papilla and pancreaticoduodenectomy if the resection line was over the duodenal papilla. Exploratory laparotomy via midline incision revealed an expanded right gastric vein, which was presumed to be the effect of the increased blood flow due to AVM. However, no abnormalities were observed in the duodenum. To determine the extent of resection, 12.5 mg of ICG (Daiichi Sankyo Co., Japan) was injected, and ICG imaging was performed using an infrared camera system (SPY-PHI portable handheld imager, Striker, USA). Intraoperative ICG angiography clearly demonstrated the lesion of the AVM, and this area was completely resected after IPA and SDA ligation, as planned preoperatively (Fig. 3). The cut end of the duodenum was sutured and embedded. The anastomosis between the stomach and the jejunum was made by the anterior colonic route. In addition, the Brown anastomosis was added. The operation time was 221 min, and the estimated blood loss was 60 mL. No intraoperative blood transfusion was required. Pathological findings showed dense vascularity from the layers of the mucosa to the subserosa, which was confirmed as an AVM of the duodenum. In addition, extravascular leakage of red blood cells was observed in the subserosa, which was reasonable to consider as a source of GI bleeding (Fig. 4). The postoperative course was uneventful, and he was discharged on postoperative day 11. At the 6-month follow-up, he was doing well and denied any signs of re-bleeding.

Intraoperative images. a Dilatation of the right gastric vein is found. Duodenal appearance has no remarkable change. b Indocyanine green is injected and observed with the infrared camera. The lesion and the boundary of the arteriovenous malformation are made clear (dotted line area). c Inflow vessels branching from the gastroduodenal artery are ligated (arrowheads), and the area from the pyloric ring to the duodenum is resected

Discussion

AVM is characterized by a nidus, which is an abnormal connection between the arteries and veins without capillaries. No definite pathogenetic explanation has been described for this anomaly. The majority of lesions are congenital and are associated with hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia, such as Osler–Weber–Rendu syndrome, whereas an acquired case has also been reported. In the present case, he had no nasal bleeding, vasodilation of body surface, or family history, which are all physical features suggestive of a hereditary disease; thus, we consider him to be a solitary AVM [3, 4]. AVM of the GI tract is clinically important as a cause of bleeding, because angiodysplasias and vascular malformations reportedly cause approximately 5% of non-variceal upper GI tract bleedings [1]. AVM of the GI tract is most often located in the cecum and the right side of the colon; however, AVM located in the duodenum is rare and reported to make up 2.3% of all AVM of the GI tract [5].

The treatment of choice for GI tract AVM is surgical resection of the involved bowel segment with complete resection of the nidus. Because AVMs located in the duodenum or pancreatic head can cause bleeding from the duodenum, there are several case reports in which pancreaticoduodenectomy was performed as treatment [6,7,8,9]. To determine the resection area, precise identification of AVM area is important. Intraoperative identification of nidus using ICG angiography in patients with AVM of the central nervous system has been reported in several cases [10]. However, to the best of our knowledge, only three reports of ICG angiography for the GI tract AVM have been reported [11,12,13], and all of these reports were about AVMs of the small intestine. Therefore, this is the first case of using ICG angiography for duodenal AVM. Since there are important blood vessels and bile ducts running around the duodenum, it is very important to set the exact resection area. In the present case, we successfully performed ICG angiography for intraoperative identification of the duodenal AVM, and we believe that it allowed us to perform precise and organ-preserving surgery in a less invasive manner. On the other hand, ICG angiography prolongs the operation time due to drug administration and observation and may also cause drug allergy. Even with these demerits, we believe that ICG angiography is particularly useful in cases, such as ours, in which a small change in the resection line can significantly affect the surgical procedure.

Another option, treatment with the transarterial embolization (TAE), has been reported as a non-surgical treatment for AVMs [14, 15]. The problem with TAE is that it increases the risk of re-bleeding and portal hypertension due to the development of collateral vessels, and it also includes the risk of enteric necrosis [16]. Furthermore, it is reported that once portal hypertension develops, it is impossible to reduce portal venous hypertension even if the AVM is surgically removed [17]. Considering these factors, we believe that it is effective to stabilize the general condition by TAE for patients with acute gastrointestinal bleeding due to AVM who are in poor general condition, but it is important to perform surgery afterwards. In other reports, TAE was performed preoperatively to reduce blood loss during surgery, not as a curative treatment [18, 19]. However, in our case, we identified the inflow arteries by preoperative angio-CT and successfully controlled intraoperative blood loss by ligating these vessels first. Precise preoperative imaging diagnosis also contributed to the safe performance of surgical operation.

Conclusions

Intraoperative ICG angiography was useful in identifying the location of the AVM lesion. Using this technique, we could resect the duodenal AVM in the appropriate area.

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- AVM:

-

Arteriovenous malformation

- GI:

-

Gastrointestinal

- ICG:

-

Indocyanine green

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- IPA:

-

Inferior pyloric artery

- SDA:

-

Superior duodenal artery

- TAE:

-

Transarterial embolization

References

Ferguson CB, Mitchell RM. Non-variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Ulster Med J. 2006;75:32–9.

Fujii T, Morita H, Sutoh T, Takada T, Tsutsumi S, Kuwano H. Arteriovenous malformation detected by small bowel endoscopy. Case Rep Gastroenterol. 2014;8:324–8.

Matti E, Lizzio R, Ugolini S, Maiorano E, Zaccari D, De Silvestri A, et al. Nasal endoscopy in the clinical diagnosis of hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. J Pediatr. 2021;238:74-79.e2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2021.07.007.

Bofarid S, Hosman AE, Mager JJ, Snijder RJ, Post MC. Pulmonary vascular complications in hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia and the underlying pathophysiology. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22

Meyer CT, Troncale FJ, Galloway S, Sheahan DG. Arteriovenous malformations of the bowel: an analysis of 22 cases and a review of the literature. Med (Baltim). 1981;60:36–48.

Kato S, Kobayashi N, Kubota K, Kirikoshi H, Watanabe S, Ogawa M, et al. A duodenal mucosal lesion coming from pancreatic arteriovenous malformation. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71:1299–300.

Perera MT, Shimoda M, Kato M, Abe A, Yamazaki R, Sawada T, et al. Life-threatening bleeding from duodenal varices due to pancreatic arterio-venous malformation: role of emergency pancreatoduodenectomy. Hepatogastroenterology. 2008;55:1553–6.

Arora A, Tyagi P, Kirnake V, Singla V, Sharma P, Bansal N, et al. Unusual cause of massive upper gastrointestinal bleeding: a pancreatic arteriovenous malformation. JOP. 2013;14:292–5.

Nishiyama R, Kawanishi Y, Mitsuhashi H, Kanai T, Ohba K, Mori T, et al. Management of pancreatic arteriovenous malformation. J Hepato-Bil Pancreat Surg. 2000;7:438–42.

Takamiya S, Yamazaki K, Tokairin K, Osanai T, Shindo T, Seki T, et al. Intraoperative identification of the shunt point of spinal arteriovenous malformations by a selective arterial injection of saline to subtract signals of indocyanine green: technical note [Technical note]. World Neurosurg. 2021;151:132–7.

Hirakawa M, Ishizuka R, Sato M, Hayasaka N, Ohnuma H, Murase K, et al. Management of multiple arteriovenous malformations of the small bowel. Case Rep Med. 2019;2019:2046857.

Hyo T, Matsuda K, Tamura K, Iwamoto H, Mitani Y, Mizumoto Y, et al. Small intestinal arteriovenous malformation treated by laparoscopic surgery using intravenous injection of ICG: case report with literature review. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2020;74:201–4.

Ono H, Kusano M, Kawamata F, Danjo Y, Kawakami M, Nagashima K, et al. Intraoperative localization of arteriovenous malformation of a jejunum with combined use of angiographic methods and indocyanine green injection: report of a new technique. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2016;29:137–40.

Poon RT, Poon J. Massive GI bleeding due to a duodenal arteriovenous malformation. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;52:101–4.

Goldin AR, Dent DM, Davies PG. Angiography in the diagnosis and management of duodenal arteriovenous malformation. A case report. S Afr Med J. 1979;55:347–8.

Korai T, Kimura Y, Imamura M, Nagayama M, Kanazawa A, Miura R, et al. Arteriovenous malformation in the pancreatic head initially mimicking a hypervascular mass treated with duodenum-preserving pancreatic head resection: a case report. Surg Case Rep. 2020;6:301.

Van Way CW, Crane JM, Riddell DH, Foster JH. Arteriovenous fistula in the portal circulation. Surgery. 1971;70:876–90.

Abe T, Suzuki N, Haga J, Azami A, Todate Y, Waragai M, et al. Arteriovenous malformation of the pancreas: a case report. Surg Case Rep. 2016;2:6.

Song KB, Kim SC, Park JB, Kim YH, Jung YS, Kim MH, et al. Surgical outcomes of pancreatic arteriovenous malformation in a single center and review of literature. Pancreas. 2012;41:388–96.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.com) for English language editing.

Funding

The authors did not receive any Grant or funding source.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors attest that they meet the criteria for authorship. YK and KH performed the operation and wrote the manuscript. KM was in charge of pathological diagnosis. HM, MU, KM, MK, TT, YM, HS, TI, GI, HH and HM helped to draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Approval was obtained from the appropriate ethics review board of our institution. The procedures used in this study adhere to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kurata, Y., Hayano, K., Matsusaka, K. et al. A case report of duodenal arteriovenous malformation: usefulness of intraoperative indocyanine green angiography for precise identification of the lesion. surg case rep 8, 4 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40792-021-01356-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40792-021-01356-8