Abstract

Background

Spontaneous common bile duct (CBD) perforation is an extremely rare disease in adults. We report an adult case of CBD perforation due to choledocolithiasis accompanied with pancreaticobiliary maljunction, which is, to our knowledge, the first such case report based on a search using PubMed.

Case presentation

A 71-year-old woman with consciousness disorder was transported to the emergency department of another hospital. She was diagnosed as having severe peritonitis with septic shock and transferred to our hospital for emergency surgery. Enhanced computed tomography (CT) revealed supraduodenal CBD dilation similar to a diverticulum and a defect of bile duct wall continuity. Furthermore, CT showed a long common channel of the pancreaticobiliary duct, so she was diagnosed as having spontaneous CBD perforation with pancreaticobiliary maljunction. Emergency surgery was performed that revealed a necrotic diverticulum-like change on the supraduodenal part, and a 2.5 × 1 cm perforation was found on the anterolateral wall of the CBD. Peritoneal lavage was performed, and CBD perforation was resolved with a T-tube. The patient suffered refractory intra-abdominal and retroperitoneal abscess formation and bleeding from the abdominal wall, which required a long period of postoperative management. The T-tube was removed on day 136, and the patient was transferred on day 153.

Conclusion

The cause of CBD perforation is commonly considered to be increased intraductal pressure or weakness of the bile duct wall. In this case, pancreaticobiliary maljunction may have significantly influenced onset and the postoperative course. This case suggests that early surgical intervention and appropriate drainage are important to ensure survival.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Spontaneous common bile duct (CBD) perforation has been described as a perforation of the CBD without traumatic or iatrogenic injury [1]. It is rarely seen in infants and children with choledochal cyst and pancreaticobiliary maljunction and is extremely rare in adults. According to past reports of adult cases, it may be related to either single or multiple factors such as obstruction by a confluent stone [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10] or tumor infiltration [11], infective necrosis [12], and increased intraductal pressure [11]. We report an adult case of spontaneous CBD perforation due to choledocolithiasis accompanied with pancreaticobiliary maljunction, previous reports of which were not found in a search using PubMed (United States National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). Thus, this report includes some important and clinically significant information.

Case presentation

A 71-year-old woman was transported to the emergency department of another hospital because of consciousness disorder. Enhanced computed tomography (CT) showed an amount of free fluid in the peritoneal cavity mainly around the right upper abdomen without free air. Ultrasonography identified cholecystolithiasis. Paracentesis revealed intra-abdominal bilious fluid with high levels of total bilirubin (21.6 mg/dL) and amylase (8697 U/L) on biochemical examination. She was diagnosed as having severe peritonitis with septic shock and was transferred to our hospital for emergency surgery and intensive care management.

She had no history of past abdominal operations, and other past medical history included choledocholithiasis and pancreatitis. Hematological investigations on admission revealed coagulopathy, renal dysfunction, and circulatory insufficiency (Table 1), which indicated septic disseminated intravascular coagulation. Significantly high levels of serum transaminases, bilirubin, and pancreatic enzymes suggested a condition associated with biliary tract disease. As shown in Fig. 1, enhanced CT revealed that the supraduodenal CBD was markedly dilated similar to a diverticulum (arrow), and the bile duct wall had a partial defect in continuity (arrowhead). Moreover, the common channel of the pancreaticobiliary duct was long at 9.3 mm in length and seemed to be joined outside the muscular layer of the duodenal papilla (arrow) on the coronal CT view (Fig. 2). Eventually, we diagnosed biliary panperitonitis due to the spontaneous CBD perforation accompanied with congenital biliary dilatation and pancreaticobiliary maljunction. As her general condition improved following adequate primary resuscitation, she was able to undergo an emergency laparotomy to cure her septic peritonitis.

Preoperative computed tomography (coronal view). The common channel of the pancreaticobiliary duct (arrow) was long at 9.3 mm in length and seemed to be joined outside the muscular layer of the duodenal papilla on the enhanced computed tomography coronal view. The dilated common bile duct was accompanied by a diverticulum-like change (arrowhead)

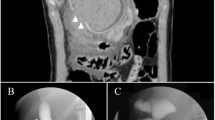

Intraoperative findings revealed a large amount of bilious ascites along with edematous omentum. No perforation was apparent either in the gallbladder or the gastrointestinal tract. A necrotic diverticulum-like change with bile leakage was present on the supraduodenal part of the CBD. After the necrotic lesion was removed, a 2.5 × 1 cm perforation was found on the anterolateral wall of the CBD, below the junction of the common hepatic duct and cystic duct (Fig. 3a, b). Intraoperative cholangioscopy revealed an impacted stone in the major duodenal papilla (Fig. 3c), but the stone could not be removed easily intraoperatively. The cholecystectomy was performed. The gallbladder showed edematous changes due to inflammation, but was easily dissected. Thorough peritoneal lavage was performed, and the CBD perforation was resolved with a T-tube inserted through the perforation (Fig. 3d). Based on the preoperative examination and intraoperative findings, the patient was diagnosed as having a perforation of the CBD caused by a combination of congenital biliary dilatation with pancreaticobiliary maljunction, type II by Todani’s classification, and gallstone cholangitis/pancreatitis. Hematoxylin and eosin staining revealed that the resected specimen of the CBD wall was so destroyed that the muscular layer lacked continuity (Fig. 4a). Furthermore, immunohistochemical examination with anti-desmin antibody did not show the presence of smooth muscle in the tissue (Fig. 4b). Gallbladder wall revealed that dilated Rokitansky–Aschoff sinuses, mild muscular hyperplasia, and lymphocytic infiltration with hematoxylin–eosin staining.

Operative findings. Intraoperative findings revealed that a necrotic diverticulum-like change with bile leakage was present on the supraduodenal part. After removing the necrotic lesion, we found a single 2.5 × 1 cm perforation on the anterolateral wall of the common bile duct (a). The above findings are shown in the schema (b). Intraoperative cholangioscopy revealed an impacted stone in the major duodenal papilla (c). A T-tube was inserted through the perforation (d)

The patient remained unstable and required inotropic agents, artificial respirator support and continuous hemodiafiltration in the intensive care unit until postoperative day 10. Furthermore, multiple additional drainage, and administration of antibacterial and antifungal agents were required for the refractory intra-abdominal and retroperitoneal abscesses. On day 16, active bleeding was observed at the abdominal wall around the T-tube, and hemostasis was achieved by transcatheter arterial embolization. On day 55, T-tube cholangiography revealed that the impacting CBD stone had disappeared naturally and, thus, the long common channel of the pancreaticobiliary duct and the diagnosed pancreaticobiliary maljunction could be observed (Fig. 5). After removal of the T-tube on day 136, she was transferred to the hospital for recuperation on day 152.

Discussion

Spontaneous CBD perforation is one of the rare presentations of acute abdomen in infants and children and is extremely rare in adults. It was first described by Freeland in 1882 [13]. Either weakness in the wall of the bile duct or an increase in intraductal pressure or both have been suggested as the cause of the perforation [11]. Fragility of the bile duct wall is considered to be caused by choledochal cysts [14, 15], pancreatitis [15, 16], chronic infection [12], congenital weakness [11], ischemia [11], pancreatic reflux [11], and torsion of the gallbladder [11]. In contrast, reported causes of perforation with increased intraductal pressure include biliary sludge or stones [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10], tumors [11], congenital stenosis of the ampulla of Vater [11], spasm of sphincter of Oddi [11], protein plugs [11], and parasites [11]. Diagnosis of the pathogenesis is difficult and delayed, because it sometimes occurs idiopathically.

In our search of PubMed between 2001 and 2021, we found 23 adult case reports of spontaneous extrahepatic CBD perforation with a detailed clinical course (Table 2) [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12, 14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24]. We summarized these results to better understand the clinical features of the disease (Table 3). The summary showed that CBD perforation occurred more frequently in women. The mean age of the reported cases was 42 years (17–84 years). The mean duration of symptoms was approximately 2 weeks, which seems to be long compared to that of the usual acute abdomen, such as that caused by gastrointestinal perforations. We suppose that background diseases, which cause increased intraductal pressure or wall weakness, take relative longer to develop into a perforation. Choledocholithiasis was found in 10 cases (43.5%), most of which were accompanied with cholangitis or pancreatitis. These are considered to be typical cases in which the complex causes were consistent with increased intraductal pressure by stone impaction and wall weakening due to inflammation [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10]. CBD perforation associated with pregnancy was observed in seven cases (30.4%), and all but one case developed in the third trimester. Although the relationship between pregnancy and CBD perforation is unclear, hemodynamic changes associated with higher pressure in the vena cava [2], raised intra-abdominal pressure [15], or global arteriolar spasm and impaired microcirculation due to preeclampsia [8] were mentioned as causes.

Although we could preoperatively diagnose CBD perforation with bilious ascites and discontinuity of the bile duct wall as proven by CT in our patient, only four cases (17.4%) in this review could be diagnosed preoperatively. In these cases, the authors reported that the loss of bile duct wall continuity on CT and high bilirubin levels in ascites were important diagnostic factors [4, 16, 23, 24]. Although most of the other cases were diagnosed by exploratory laparotomy, the perforation site in some cases could not be identified intraoperatively and required subsequent re-operation [5] or endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography [3] for diagnosis. Notably, in a few cases, the perforation site could not be identified intraoperatively despite bile duct perforation being suspected preoperatively [1, 3]. In our summary, the most common site of perforation is the supra-duodenum (50%), followed by the junction of the cystic duct (22.7%). It may be helpful to observe these predominant sites when the perforation cannot be detected intraoperatively.

Surgical intervention is an effective treatment for CBD perforation as shown in our case. It is important to drain the abdominal contamination caused by the infected bilious peritoneal fluid. In most cases, T-tube drainage was followed by elective treatment for the causative diseases, such as endoscopic lithotomy for choledocholithiasis, resection of an extrahepatic bile duct, and hepaticojejunostomy for congenital biliary dilation. In cases diagnosed as idiopathic after detailed evaluation, the T-tube was removed without additional treatment. As a result of this review, we recommend prompt and appropriate peritoneal and biliary drainage in the unstable phase with peritonitis, followed by accurate assessment of the necessity of additional treatment for the background disease in the stable phase.

Postoperatively, our patient suffered from refractory intra-abdominal and retroperitoneal abscesses and the hemorrhagic shock due to the rupture of an aneurysm formed along the T-tube fistula. Our review indicated that postoperative complications such as bile leakage or intraabdominal abscess were reported in 30.4% of the cases. Compared to the patients in the literature review, our patient required more time for treatment of postoperative complications, and we considered that one of the reasons was due to the mechanism of pancreaticobiliary maljunction. Pancreaticobiliary maljunction is generally accepted as a congenital condition in which the pancreatic and bile ducts join anatomically outside the duodenal wall. Because the action of the sphincter of Oddi does not affect the pancreaticobiliary junction, pancreaticobiliary reflux occurs. As a result, various pathologic conditions, such as obstruction of bile and pancreatic outflow, carcinoma, or inflammation, can occur [25]. In the present case, abscess formation and bleeding from the abdominal wall were considered specific postoperative complications, because pancreatic enzymes were activated by mixing with bile due to reflux of pancreatic juice into the bile duct. The main cause of aneurysms associated with pancreatic fistulas is corrosion and weakening of the vessel wall caused by leaking activated pancreatic juice [26]. The abdominal wall aneurysm in our case might have occurred due to a mechanism similar to that described above.

One of the clinical questions in the presented case is whether the diverticulum-like imaging finding of CBD was due to the coexistence of congenital biliary dilation, type II by Todani’s classification, or secondary changes associated with perforation. Glenn et al. suggested that congenital biliary dilatation that forms a diverticulum may be due to hypoplasia of the bile duct wall muscularis [27]. Previous reports have shown the presence of a thinning muscularis [28]. We thought that the pathological evaluation of the resected specimen might help to distinguish this. Hematoxylin and eosin staining and immunohistochemical examination with anti-desmin antibody were performed, but neither showed a muscular layer. Even if the muscular layer were present, it would have been difficult to distinguish it because of the strong tissue destruction caused by inflammation. As a result, although we finally judged that congenital biliary dilation could not be definitely diagnosed, it could be a possibility based on the imaging findings.

Conclusion

This is the first case report of spontaneous CBD perforation accompanied with pancreaticobiliary maljunction. Early surgical treatment and appropriate perioperative management prevented mortality in our patient. Spontaneous CBD perforation should be considered in the differential diagnosis if the perforation cannot be identified during exploratory laparotomy.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Abbreviations

- CBD:

-

Common bile duct

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

References

Hamura R, Haruki K, Tsutsumi J, Takayama S, Shiba H, Yanaga K. Spontaneous biliary peritonitis with common bile duct stones: report of a case. Surg Case Rep. 2016;2:103. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40792-016-0234-6.

Balsarkar DJ, Subramaniyan P, Joshi MA. Spontaneous perforation of the common bile duct in pregnancy. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2001;20(5):198–9.

McGrath BA, Singh M, Singh T, Maguire S. Spontaneous common bile duct rupture in pregnancy. Int J Obstet Anesth. 2005;14(2):172–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijoa.2004.10.006.

Marwah S, Sen J, Goyal A, Marwah N, Sharma JP. Spontaneous perforation of the common bile duct in an adult. Ann Saudi Med. 2005;25(1):58–9. https://doi.org/10.5144/0256-4947.2005.58.

Dabbas N, Abdelaziz M, Hamdan K, Stedman B, Abu HM. Gallstone-induced perforation of the common bile duct in pregnancy. HPB Surg. 2008;2008: 174202. https://doi.org/10.1155/2008/174202.

Bhattacharjee PK, Choudhury D, Rai H, Ram N, Chattopadhyay D, Roy RP. Spontaneous perforation of common bile duct: a rare complication of choledocholithiasis. Indian J Surg. 2009;71(2):92–4. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12262-009-0024-5.

Khanna R, Agarwal N, Singh AK, Khanna S, Basu SP. Spontaneous common bile duct perforation presenting as acute abdomen. Indian J Surg. 2010;72(5):407–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12262-010-0113-5.

Bediako-Bowan AA, Dakubo JC, Asempa M. Spontaneous extra-hepatic bile duct perforation postpartum. Ghana Med J. 2013;47(4):204–7.

Ishii K, Matsuo K, Seki H, Yasui N, Sakata M, Shimada A, et al. Retroperitoneal biloma due to spontaneous perforation of the left hepatic duct. Am J Case Rep. 2016;17:264–7. https://doi.org/10.12659/ajcr.897612.

Subasinghe D, Udayakumara EA, Somathilaka U, Huruggamuwa M. Spontaneous perforation of common bile duct: a rare presentation of gall stones disease. Case Rep Gastrointest Med. 2016;2016:5321304. https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/5321304.

Mohanty SK, Mahapatra T, Behera BK, Acharya B, Kumar S, Dash JR, et al. Spontaneous perforation of common bile duct in a young female: an intra-operative surprise. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2017;35:17–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijscr.2017.04.002.

Paramhans D, Shukla S, Grover J. Spontaneous perforation of the common bile duct in an adult. Indian J Surg. 2013;75(Suppl 1):376–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12262-012-0512-x.

Freeland J. Rupture of the hepatic duct. Lancet. 1882;119:731–2.

Joseph P, Raju RS, Vyas FL, Sitaram V. Spontaneous perforation of choledochal cyst and hyperemesis gravidarum. Trop Gastroenterol. 2008;29(1):46–7.

Singh H, Gupta R, Dhaliwal L, Singh R. Spontaneous choledochal cyst perforation in pregnancy with co-existent chronic pancreatitis. BMJ Case Rep. 2014. https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2014-207183.

Pülat H, Karaköse O, Benzin MF, Sabuncuoğlu MZ, Çetin R. A rare cause of acute abdomen: spontaneous common hepatic duct perforation. Ulus Travma Acil Cerrahi Derg. 2016;22(1):103–5. https://doi.org/10.5505/tjtes.2015.95142.

Rege SA, Lambe S, Sethi H, Gandhi A, Rohondia O. Spontaneous common bile duct perforation in adult: a case report and review. Int Surg. 2002;87(2):81–2.

Jarmin R, Alwi RI, Shaharuddin S, Salleh KM, Gunn A. Common bile duct perforation due to tuberculosis: a case report. Asian J Surg. 2004;27(4):342–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1015-9584(09)60065-8.

Talwar N, Andley M, Ravi B, Kumar A. Spontaneous biliary tract perforations: an unusual cause of peritonitis in pregnancy. Report of two cases and review of literature. World J Emerg Surg. 2006. https://doi.org/10.1186/1749-7922-1-21.

Karvonen J, Gullichsen R, Salminen P, Laine S, Grönroos JM. Successful endoscopic treatment of spontaneous perforation of the common hepatic duct. Endoscopy. 2009;41(Suppl 2):E224–5. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0029-1214926.

Yaşar NF, Yaşar B, Kebapçı M. Spontaneous common bile duct perforation due to chronic pancreatitis, presenting as a huge cystic retroperitoneal mass: a case report. Cases J. 2009;2:6273. https://doi.org/10.4076/1757-1626-2-6273.

Laway MA, Bakshi IH, Shah M, Paray SA, Malla MS. Biliary peritonitis due to spontaneous perforation of choledochus: a case report. Indian J Surg. 2013;75(Suppl 1):96–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12262-011-0351-1.

Huda F, Naithani M, Singh KS, Saha S. Ascitic fluid/serum bilirubin ratio as an aid in preoperative diagnosis of choleperitoneum in a neglected case of spontaneous common bile duct perforation. Euroasian J Hepatogastroenterol. 2017;7(2):185–7. https://doi.org/10.5005/jp-journals-10018-1246.

Amberger M, Burton N, Tissera G, Baltazar G, Palmer S. Spontaneous common bile duct perforation-a rare clinical entity. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2018;46:34–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijscr.2018.03.030.

The Japanese Study Group on Pancreaticobiliary Maljunction (JSPBM). The Committee of JSPBM for diagnostic criteria for pancreaticobiliary maljunction diagnostic criteria for pancreaticobiliary maljunction 2013. Tando. 2013;27:785–7.

Kanazawa A, Tanaka H, Hirohashi K, Shuto T, Takemura S, Tanaka S, et al. Pseudoaneurysm of the dorsal pancreatic artery with obstruction of the celiac axis after pancreatoduodenectomy: report of a case. Surg Today. 2005;35(4):332–5. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00595-004-2937-8.

Glenn F, McSherry CK. Congenital segmental cystic dilatation of the biliary ductal system. Ann Surg. 1973;177:705–13. https://doi.org/10.1097/00000658-197306000-00009.

Yamauchi K, Ozeki Y, Sumi Y, Yamada T. A case of congenital choledochal dilatation of type II in Alonso-Lej’s classification. Jpn J Gastro Enterol. 2000;97:1048–52.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The authors declare no sources of funding for this case report.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RS principally wrote the case report. KK, MH, NI, KY, TH, TN, FK, DS, YU, KY and HK performed the literature review. AN approved the final version of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All procedures used in this case presentation were approved by the Ethical Committee of the University of Miyazaki Faculty of Medicine.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for the publication of this case report and any accompanying images.

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflicts of interest in association with the present study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sakamoto, R., Kai, K., Hiyoshi, M. et al. Spontaneous common bile duct perforation due to choledocolithiasis accompanied with pancreaticobiliary maljunction in an adult: a case report. surg case rep 7, 205 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40792-021-01290-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40792-021-01290-9