Abstract

Background

The occurrence of schwannomas in the hepatoduodenal ligament is rare, and its preoperative accurate diagnosis is difficult. Only few cases have been treated with laparoscopic surgery.

Case presentation

A 54-year-old man visited our hospital following abnormal abdominal computed tomography findings. He had no complaints, and his laboratory investigations were normal. Abdominal contrast-enhanced computed tomography revealed a tumor with enhancement at the margin of the hepatoduodenal ligament. The abdominal magnetic resonance imaging findings of the tumor showed hypointensity on the T1-weighted images and mixed hypointensity and hyperintensity on the T2-weighted fat-suppression images. Positron emission tomography showed localized accumulation of fludeoxyglucose only in the hepatoduodenal ligament tumor. The patient underwent laparoscopic tumor resection for accurate diagnosis. Histopathologically, the tumor was mainly composed of spindle cells, which were strongly positive for S-100 protein on immunohistochemical staining. The patient was discharged without any postoperative complications on day 5.

Conclusions

Complete tumor resection is essential for schwannomas to avoid recurrence. Laparoscopic surgery is useful for schwannomas occurring in the hepatoduodenal ligament and can be performed safely by devising an appropriate surgical method.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Schwannomas are mesenchymal neoplasms originating from the Schwann cells, which are the neuroglial cells surrounding the peripheral nerves [1]. They can occur in any part of the body, such as the head, neck, trunk, or extremities [1]. Retroperitoneal and gastric schwannomas are the most common types of schwannomas occurring in the abdominal cavity [2, 3]. However, schwannomas in the hepatoduodenal ligament are extremely rare, and only a few case reports have described their laparoscopic resection.

Herein, we present a case of laparoscopic resection of schwannoma in the hepatoduodenal ligament that was unexpectedly detected on abdominal computed tomography (CT).

Case presentation

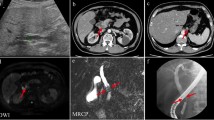

A 54-year-old man was admitted to the Department of Surgery at our hospital following abnormal abdominal CT findings. He had no complaints, such as upper abdominal pain or abdominal distension. He presented with comorbidities of neurogenic bladder due to spinal cord injury and sleep apnea syndrome. His past history included previous surgeries for appendicitis and renal stones in the left kidney. The laboratory data showed normal findings. Abdominal contrast-enhanced CT revealed a tumor in the hepatoduodenal ligament, measuring 40 mm, with enhancement at its margin in the arterial phase; the enhancement was prolonged in the delayed phase (Fig. 1a, b). The boundary between the tumor and the caudate lobe of the liver was unclear. The abdominal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed that the tumor was hypointense on T1-weighted images and both hypo- and hyperintense on T2-weighted fat-suppression images (Fig. 2a, b). Moreover, the contrast MRI showed that the margin of the tumor was enhanced in the arterial phase (Fig. 2c). The boundary between the tumor and the liver was clear; hence, the tumor was considered an extrahepatic lesion. Positron emission tomography (PET) revealed localized accumulation of fludeoxyglucose (FDG) (5.9 F) in the hepatoduodenal ligament tumor (Fig. 3). The biopsy was difficult to perform due to the location of the lesion. Although no preoperative diagnosis was made, surgical intervention was planned for an accurate diagnosis. The patient underwent 5-port laparoscopic surgery for tumor resection. Perioperatively, the tumor was found to be located on the left side of the portal vein and on the ventral side of the inferior vena cava (Fig. 4a–c). The tumor was surrounded by a fibrous capsule and did not infiltrate the other organs. In the operative technique used, the proper hepatic artery and common hepatic artery were taped at three sites (Fig. 4d). Each tape was used for traction in order to proceed with smooth and safe tumor resection. The total operative time was 273 min, and the total intraoperative blood loss was minimal. Macroscopic examination of the specimen showed an elastic, hard tumor measuring 40 × 30 mm with a smooth surface and fibrous capsule (Fig. 5). The cross-section of the tumor was milky white in color. Histopathologically, the peripheral nerve was near the tumor. The tumor was mainly composed of spindle cells and hypercellular (Antoni type A) and hypocellular (Antoni type B) areas (Fig. 6a). Immunohistochemical staining revealed that the tumor was strongly positive for S-100 protein (Fig. 6b), but had an extremely low Ki-67 positive rate. The patient was diagnosed with low-grade schwannoma. The postoperative course was uneventful, and the patient was discharged on postoperative day 5.

Abdominal magnetic resonance imaging findings. a The tumor (white arrow) showed hypointensity on T1-weighted images. b The tumor (white arrow) showed mixed hypointensity and hyperintensity on T2-weighted fat-suppression images. c Abdominal contrast-enhanced MRI revealed that the peripheral margin of the tumor (white arrow) was enhanced in the arterial phase. MRI magnetic resonance imaging

Intraoperative findings. a The first observation of the tumor (white arrow), before the resection, is observed. The tumor was located under the caudate lobe of the liver (white arrowhead). b, c The tumor (white arrowhead) was located on the left side of the portal vein (white arrow) and on the ventral side of the inferior vena cava (white arrow). d The strings taping the proper hepatic artery and common hepatic artery (white arrow) were used for traction

Histopathological findings. a The tumor was mainly composed of spindle cells and hypercellular (Antoni type A) (black arrow) and hypocellular (Antoni type B) (black arrowhead) areas (hematoxylin–eosin stain, original magnification × 400). b Immunohistochemical investigations revealed that the tumor was strongly positive for S-100 protein

Discussion

Most schwannomas are benign and account for approximately 5% of the benign soft tissue neoplasms [4, 5]. Although schwannomas often originate as solitary neoplasms, around 10% of them originate as multiple neoplasms [6]. The incidence rate of schwannomas is not related to sex or race. They are most commonly found in middle-aged patients (20–50 years old) [1, 4]. Some case reports have reported the occurrence of schwannomas in the abdominal viscera, such as the retroperitoneum [2, 7], stomach [3], gallbladder [8], pancreas [9, 10], bowel mesentery [11], colon [12, 13], and liver [14]. However, schwannomas in the hepatoduodenal ligament are extremely rare, and there are only few case reports on them. Since 1993, several reports have demonstrated schwannomas in the hepatoduodenal ligament, as shown in Table 1 [15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22]. The characteristics of nine cases with schwannoma in the hepatoduodenal ligament, including our case, were as follows: mean age, 49 years (range, 29–70 years) and female-to-male prevalence ratio, 1:2. Most cases were asymptomatic, and only one case reported the presence of two tumors.

Generally, contrast-enhanced CT findings of schwannomas show a hypodense mass with peripheral enhancement [23]. The MRI findings usually present as hypointensity on T1-weighted images and mixed hypointensity and hyperintensity on T2-weighted images [24, 25]. Schwannomas demonstrate accumulation of FDG on PET, and increased FDG uptake in the schwannomas is associated with malignancy [26, 27]. However, accurate preoperative diagnosis is difficult due to its nonspecific imaging characteristics and clinical symptoms. A definitive diagnosis of schwannomas can be made by histopathological and immunohistochemical examinations. Notably, only one report preoperatively diagnosed the schwannoma in the hepatoduodenal ligament by endoscopic ultrasound-fine needle aspiration [21]. The main components of the schwannomas include spindle-shaped cells and mixed hypercellular and hypocellular areas [14]. Such variation in cell density contributes to the heterogeneous and hyperintense images on T2-weighted MRI. Schwannomas test positive for S-100 protein and negative for desmin, smooth muscle actin, CD34, and CD117 [28, 29].

The main treatment of schwannomas is surgical resection. There was one case where a benign schwannoma turned malignant [28]. Notably, benign schwannomas rarely recur [30]. Complete excision without lymph node dissection is important for curative treatment [18, 31]. In 2016, Tao et al. [17] reported the first case treated by laparoscopic surgery. The previous case reports (Table 1) show that only three cases underwent laparoscopic resection, and their tumor sizes were less than 50 mm. In our case, a preoperative diagnosis was not made. We planned the laparoscopic approach to observe whether the origin of the tumor was intrahepatic or extrahepatic. During the surgery, laparoscopic surgery could be continued, because the tumor was surrounded by a fibrous capsule and no other organs were infiltrated. If there is infiltration in the surrounding organs, it is important to convert the laparoscopic surgery to laparotomy surgery for curative treatment. The traction of blood vessels surrounding the tumor proved extremely useful in expanding the surgical field. With the laparoscopic operative method, the surgery proceeded smoothly and safely.

Conclusions

We encountered a rare case of schwannoma in the hepatoduodenal ligament that was laparoscopically resected. Depending on the clinical conditions, such as tumor size and no findings of infiltration in the surrounding organs, laparoscopic surgery for schwannomas in the hepatoduodenal ligament can be extremely useful.

Availability of data and materials

No applicable.

Abbreviations

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- PET:

-

Positron emission tomography

- FDG:

-

Fludeoxyglucose

References

Gupta TKD, Brasfield RD. Tumors of peripheral nerve origin: benign and malignant solitary schwannomas. CA Cancer J Clin. 1970;20:228–33.

Xu S-Y, Sun K, Xie H-Y, et al. Hemorrhagic, calcified, and ossified benign retroperitoneal schwannoma: first case report. Medicine. 2016;95:e4318.

Tao K, Chang W, Zhao E, et al. Clinicopathologic features of gastric schwannoma: 8-year experience at a single institution in China. Medicine. 2015;94:e1970.

Ariel IM. Tumors of the peripheral nervous system. Semin Surg Oncol. 1988. https://doi.org/10.1002/ssu.2980040104.

Pilavaki M, Chourmouzi D, Kiziridou A, et al. Imaging of peripheral nerve sheath tumors with pathologic correlation: pictorial review. Euro J Radiol. 2004;52:229–39.

Fenoglio L, Severini S, Cena P, et al. Common bile duct schwannoma: a case report and review of literature. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:1275–8.

Fass G, Hossey D, Nyst M, et al. Benign retroperitoneal schwannoma presenting as colitis: a case report. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:5521–4.

Liu L-N, Xu H-X, Zheng S-G, et al. Solitary schwannoma of the gallbladder: a case report and literature review. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:6685–90.

Ciledag N, Arda K, Aksoy M. Pancreatic schwannoma: A case report and review of the literature. Oncol Lett. 2014;8:2741–3.

Nishikawa T, Shimura K, Tsuyuguchi T, et al. Contrast-enhanced harmonic EUS of pancreatic schwannoma. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;83:463–4.

Tang S-X, Sun Y-H, Zhou X-R, Wang J. Bowel mesentery (meso-appendix) microcystic/reticular schwannoma: case report and literature review. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:1371–6.

Bugiantella W, Rondelli F, Mariani L, et al. Schwannoma of the colon: a case report. Oncol Lett. 2014;8:2511–2.

Bohlok A, El Khoury M, Bormans A, et al. Schwannoma of the colon and rectum: a systematic literature review. World J Surg Oncol. 2018;16:1–12.

Xu S-Y, Guo H, Shen Y, et al. Multiple schwannomas synchronously occurring in the porta hepatis, liver, and gallbladder: first case report. Medicine. 2016;95:e4378.

Nagafuchi Y, Mitsuo H, Takeda S, et al. Benign schwannoma in the hepatoduodenal ligament: report of a case. Surg Today. 1993;23:68–72.

Pinto J, Afonso M, Veloso R, et al. Benign schwannoma of the hepatoduodenal ligament. Endoscopy. 2011. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0030-1256354.

Tao L, Xu S, Ren Z, et al. Laparoscopic resection of benign schwannoma in the hepatoduodenal ligament: a case report and review of the literature. Oncol Lett. 2016;11:3349–53.

Xu S-Y, Sun K, Xie H-Y, et al. Schwannoma in the hepatoduodenal ligament: a case report and literature review. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:10260–6.

Liu J, Wang Q, Xie Q, et al. Benign schwannoma of the hepatoduodenal ligament: a case report. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2016;9:20349–51.

He Y-A, Yan C, Chen Y, et al. Management of Schwannoma in the hepatoduodenal ligament: a case report and review of the literature. Medicine. 2020;99:e18797.

Tomioka K, Aoki T, Koizumi T, et al. Laparoscopic treatment of a hepatoduodenal ligament schwannoma with infrared indocyanine green fluorescence. Vivo. 2020;34:2037–41.

Wang J-K, Wu Q, Wu Z-R, et al. Schwannoma in the hepatoduodenal ligament with portal vein invasion: a case report. Medicine. 2020;99:e20940.

Cohen LM, Schwartz AM, Rockoff SD. Benign schwannomas: pathologic basis for CT inhomogeneities. Am J Roentgenol. 1986;147:141–3.

Momtahen AJ, Akduman EI, Balci NC, et al. Liver schwannoma: findings on MRI. Magn Reson imaging. 2008;26:1442–5.

Rha SE, Byun JY, Jung SE, et al. Neurogenic tumors in the abdomen: tumor types and imaging characteristics. Radiographics. 2003;23:29–43.

Beaulieu S, Rubin B, Djang D, et al. Positron emission tomography of schwannomas: emphasizing its potential in preoperative planning. Am J of Roentgenol. 2004;182:971–4.

Miyake KK, Nakamoto Y, Kataoka TR, et al. Clinical, morphologic, and pathologic features associated with increased FDG uptake in schwannoma. Am J Roentgenol. 2016;207:1288–96.

Gupta TKD, Brasfield RD, Strong EW, Hajdu SI. Benign solitary schwannomas (neurilemomas). Cancer. 1969;24:355–66.

Weiss S, Langloss J, Enzinger F. Value of S-100 protein in the diagnosis of soft tissue tumors with particular reference to benign and malignant Schwann cell tumors. Lab Invest. 1983;49:299–308.

Le Guellec S. Nerve sheath tumours. Ann Pathol. 2015;35:54–70.

Yin S-y, Zhai Z-l, Ren K-w, et al. Porta hepatic schwannoma: case report and a 30-year review of the literature yielding 15 cases. World J Surg Oncol. 2016;14:1–7.

Acknowledgements

This case report was not supported by any grants. We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.com) for English language editing.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

TB, KO, SO, SF and TF performed the operation. TB, KO, and SO managed the perioperative course. TB, and KO wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

This patient consented to the reporting of this case in a scientific publication.

Competing interests

We declare no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bekki, T., Oishi, K., Tadokoro, T. et al. Laparoscopic resection of schwannoma in the hepatoduodenal ligament: a case report. surg case rep 7, 187 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40792-021-01271-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40792-021-01271-y