Abstract

Background

Liposarcoma arising from the mediastinum is rare, accounting for less than 1% of mediastinal tumors. Furthermore, a rapidly growing well-differentiated liposarcoma is extremely rare. A well-differentiated liposarcoma is usually considered a low-grade malignancy. However, we present an extremely rare case of a sclerosing variant of well-differentiated liposarcoma that grew rapidly within a year.

Case presentation

A 77-year-old man with a giant mass in the left thoracic cavity was referred to our hospital. This mass measured about 10 cm and occupied the left-sided mediastinum on a chest radiography; however, there was no abnormal finding on the previous year’s chest radiography. Chest-enhanced computed tomography revealed a well-circumscribed 11-cm mass in the left-sided anterior mediastinum. Positron emission tomography showed accumulation of fluorodeoxyglucose uptake in this tumor (maximum standard uptake value = 3.3). The radiological findings of computed tomography and positron emission tomography indicated that this tumor was a benign or low-grade malignancy; therefore, the chest radiographic findings were difficult to explain. To explain this discrepancy and establish the diagnosis, tumor resection was performed via left posterolateral thoracotomy. Intraoperatively, the left phrenic nerve and pericardium were adhered tightly to the tumor, so we resected them. The tumor was well-circumscribed and fibrous; therefore, the initial diagnosis was solitary fibrous tumor. However, based on its histopathological and immunohistochemical patterns, the tumor was diagnosed as a sclerosing variant of well-differentiated liposarcoma. Five years postoperatively, the patient remains alive with no evidence of disease recurrence.

Conclusions

A well-differentiated liposarcoma is usually considered a low-grade malignancy. Nevertheless, the giant tumor in the present case appeared within 1 year. Thus, this was an extremely rare case of a sclerosing variant of well-differentiated liposarcoma with rapid growth.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Primary mediastinal liposarcoma is rare, accounting for less than 0.5% of total liposarcomas and less than 0.13% of all mediastinal tumors [1]. Furthermore, a rapidly growing well-differentiated liposarcoma (WDLS) is extremely rare. A WDLS is usually considered a low-grade malignancy. Here, we describe an extremely rare case of a rapid growing mediastinal tumor diagnosed as a sclerosing variant of WDLS.

Case presentation

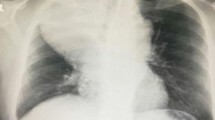

A 77-year-old man with a chief complaint of persistent dry cough had an abnormal giant mass on chest radiography (CR) and was referred to our hospital. There were no remarkable findings noted during the physical examination and in blood test results including tumor markers. The giant mass occupied the left-sided mediastinum on CR; however, there was no abnormal finding on the previous year’s CR (Fig. 1a, b). Chest-enhanced computed tomography (CT) revealed a well-circumscribed 11-cm mass in the left-sided anterior mediastinum (Fig. 1c). The mean CT value of the mass was 40 Hounsfield units (range, 20–70), and there were no areas of fatty density. Positron emission tomography-CT showed accumulation of fluorodeoxyglucose uptake in the tumor, with a maximum standard uptake value (SUVmax) of 3.3 (Fig. 1d). We preoperatively diagnosed the benign tumor as a thymoma, solitary fibrous tumor (SFT), or neurogenic tumor, or as a malignant tumor such as thymic cancer, based on the radiological evaluation.

Chest radiography showing the mass (b: dotted circle). The mass was not observed a year ago (a). Chest-enhanced computed tomography showing an approximately 11-cm mediastinal tumor occupying left internal cavity (c). Fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography showing accumulation in the tumor (maximum standard uptake value = 3.3) (d)

Tumor resection was performed without preoperative biopsy via left posterolateral thoracotomy for diagnosis and treatment. Median sternotomy is considered an alternative surgical approach for mediastinal tumors. In the present case, however, the hilar approach was considered necessary and posterolateral thoracotomy was selected. The tumor was located on the mediastinum and was suspected to invade the left phrenic nerve but not the vagus nerve. The tumor was resected with the left phrenic nerve, thymus, and a part of the pericardium (9.5 × 8.0 cm); therefore, we reconstructed the pericardium using an expanded polytetrafluoroethylene sheet (GORE-TEX®, W. L. Gore & Associates, Co., Ltd., Flagstaff, AZ, USA).

Grossly, the tumor measured 11.9 × 11.2 × 8.1 cm, and it was an elastic, well-circumscribed, yellowish, and grayish-white mass (Fig. 2a, b). Histopathologically, the tumor consisted of rich collagenous fiber and pattern-less spindle cells, and these findings suggested SFT (Fig. 2c, d). The tumor, however, comprised a few adipocytes, some of which looked like lipoblasts (Fig. 3a). Moreover, few blood vessels were recognized, and there was no “staghorn vasculature” appearance, which is characteristic of SFT.

The figure shows a few lipoblasts (a: arrows) and mitosis (b: dotted circle). Immunohistochemistry shows positivity for CD34 (c) and mouse double minute 2 (MDM2) homolog (d), and negativity for signal transducers and activator of transcription 6 (STAT6) (e). There is positivity for Ki-67, and the MIB-1 index is up to 10% (f). The tumor has partially invaded the pericardium (g: arrowheads)

Immunohistochemical staining to determine the pathological diagnosis of the tumor was performed using the Leica Bond III automated system (Leica Biosystems, Melbourne, Australia). Necrosis was absent, with up to 10% positivity of Ki-67 (clone, MIB-1; Dako, Glostrup, Denmark; diluted 1:200) (Fig. 3e). Immunohistochemistry showed positivity for CD34 in the endothelium (diluted 1:5; clone, NU-4A1; Nichirei, Tokyo, Japan) and mouse double minute 2 homolog (MDM2) in the nucleus (diluted 1:100; clone, IF2; Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Osaka, Japan) (Fig. 3c,d), while it showed negativity for signal transducers and activator of transcription 6 (STAT6) (diluted 1:200; clone, YE361; Abcam, Cambridge, United Kingdom) (Fig. 3f); these findings were consistent with a diagnosis of WDLS. Furthermore, fluorescence in situ hybridization revealed MDM2 gene amplification.

Based on its histopathological and immunohistochemical patterns, the tumor was diagnosed as a sclerosing variant of WDLS. Sarcoma staging was Fédération Nationale des Centres de Lutte Contre le Cancer (FNCLCC) grade 1 (tumor differentiation = score 1, mitotic count = score 1 [Fig. 3b], tumor necrosis = score 0, total score = 2). The tumor partially invaded the pericardium (Fig. 3 g), but not the phrenic nerve. Although gross complete resection was performed, the pathological margin was positive. Postoperative adjuvant therapies such as chemotherapy and radiotherapy were not performed because of insufficient evidence regarding their efficacy. The patient was alive at 5 years after surgery, with no evidence of disease recurrence.

Conclusions

Primary liposarcomas arising from the mediastinum are extremely rare. Enzinger and Weiss classified liposarcomas into five histologic subtypes: (1) well-differentiated, (2) myxoid, (3) round cell, (4) dedifferentiated, and (5) pleomorphic [2]. WDLSs are the least aggressive among the five subtypes; previous studies have reported a 5-year survival rate of 87.1% [3] and a recurrence rate of 40–50% [4] for all WDSLs, regardless of their origin. Furthermore, the World Health Organization subdivides WDLS into four morphologic subtypes: (1) lipoma-like (adipocytic), (2) sclerosing, (3) inflammatory, and (4) spindle cell [5]. The sclerosing variant of WDLS is second in frequency only to the lipoma-like form and characterized by the presence of multivacuolated lipoblasts, atypical fibroblasts, primitive mesenchymal cells, and abundant strands of collagen [6]. In the present case, adjuvant therapies were not performed and there was no recurrence. The role of adjuvant chemotherapy or radiotherapy in cases of liposarcoma remains poorly defined [7, 8]. Accordingly, we avoided these treatments and performed regular imaging follow-ups at short intervals. Because of the relative resistance of WDLS to systemic therapy, surgical re-resection has been considered the standard management for recurrent disease. However, patients with rapid recurrence and multifocal disease show poor outcomes, and systemic therapies can be considered in such cases [9].

We found it difficult to diagnose the tumor as WDLS on the basis of the preoperative imaging findings. Gaskin and Helms reported that thickened or nodular septa (generally > 2 mm), associated nonadipose masses, prominent foci showing a high T2 signal, and prominent areas of enhancement in magnetic resonance imaging are all associated with increased risk of WDLS [10]. Although MRI was not performed in the present case, we believe that it may have helped in preoperative differential diagnosis.

To our knowledge, there are few reports about WDLSs with rapid growth. In this case, the SUVmax, FNCLCC sarcoma grading, and MIB-1 index of the tumor were 3.3, grade 1, and up to 10%, respectively. Therefore, radiologically and histopathologically, the tumor was a low-grade malignancy. Nevertheless, this giant tumor appeared within 1 year.

There are several possible reasons for the rapid growth of the tumor. First, there are several reports that low-grade WDLSs grow rapidly secondary to intratumoral hemorrhage; however, there was no such finding in this case. Second, the dedifferentiation of a WDLS relates to rapid growth [11]. A dedifferentiated liposarcoma is defined as a non-fat-forming high-grade sarcoma developing from a WDLS, which is morphologically closely related temporally and spatially to a WDLS, and a non-fat-forming high malignant sarcoma [12]; hence, this histological finding did not match the findings of the present case. Finally, a previous report showed that the sclerosing variant of WDLS with a paucity of fat could mimic high-grade liposarcomas such as a pleomorphic liposarcoma [13]. Furthermore, the sclerosing variant of WDLS may be associated with an increased tendency toward dedifferentiation. In this case, the tumor consisted of rich collagenous fiber and spindle cells with little fatty composition. In summary, the sclerosing variant of WDLS with a paucity of fat is a potentially high-grade liposarcoma that may grow rapidly.

Because the sclerosing variant of WDLS with rapid growth has not been reported, we did not consider this as a possible differential diagnosis preoperatively. Retrospectively, we realized that the sclerosing variant of WDLS with a paucity of fat is a potentially high-grade liposarcoma. These findings indicate that the sclerosing variant of WDLS should be considered in the differential diagnosis for anterior mediastinal lesions with rapid growth; the inherent implications in management and follow-up of these tumors are yet to be determined.

Availability of data and materials

All related data are included within the article.

Abbreviations

- WDLS:

-

Well-differentiated liposarcoma

- CR:

-

Chest radiography

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- SUVmax:

-

Maximum standard uptake value

- SFT:

-

Solitary fibrous tumor

- MDM2:

-

Mouse double minute 2 homolog

- STAT6:

-

Signal transducers and activator of transcription 6

- FNCLCC:

-

Fédération Nationale des Centres de Lutte Contre le Cancer

References

Enzinger FM, Weiss SW. Liposarcoma. In: Enzinger FM, Weiss SW, editors. Soft tissue tumors. St. Louis: Mosby; 1983. p. 242–80.

Enzinger FM, Weiss SW. Soft tissue tumor. 3rd ed. St. Louis: Mosby; 1995. p. 431.

Yoon Jung O, Yi SY, Kim KH, Cho YJ, Beum SH, Lee YH, et al. Prognostic model to predict survival outcome for curatively resected liposarcoma: a multi-institutional experience. J Cancer. 2016;7:1174–80.

Henricks WH, Chu YC, Goldblum JR, Weiss SW. Dedifferentiated liposarcoma: a clinicopathological analysis of 155 cases with a proposal for an expanded definition of dedifferentiation. Am J Surg Pathol. 1997;21:271–81.

Dei Tos AP, Pedeutour F. Atypical lipomatous tumor/well differentiated liposarcoma. In: Fletcher CD, Unni KK, Mertens F, editors. World Health Organization Classification of Tumours, Pathology and Genetics of Tumours of Soft Tissue and Bone. Lyon, France: IARC Press; 2002. p. 35–7.

Shattuck MC, Victor TA. Cytologic features of well-differentiated liposarcoma in aspirated samples. Acta Cytol. 1988;32:896–901.

Chen M, Yang J, Zhu L, Zhou C, Zhao H. Primary intrathoracic liposarcoma: a clinicopathologic study and prognostic analysis of 23 cases. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2014;9:119.

Spittle MF, Newton KA, Mackenzie DH. Liposarcoma. A review of 60 cases. Br J Cancer. 1970;24:696–704.

Crago AM, Dickson MA. Liposarcoma: multimodality management and future targeted therapies. Surg Oncol Clin N Am. 2016;25:761–73.

Gaskin CM, Helms CA. Lipomas, lipoma variants, and well-differentiated liposarcomas (atypical lipomas): results of MRI evaluations of 126 consecutive fatty masses. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2004;182:733–9.

Saito D, Oda M, Yamato T, Imai T, Tatsuzawa Y, Sato K. Rapidly growing mediastinal dedifferentiated liposarcoma. Haigan. 2013;53:767–70.

Enzinger FM, Winslow DJ. Liposarcoma. A study of 103 cases. Virchows Arch Pathol Physical Klin Med. 1962;335:367–88.

Bestic JM, Kransdorf MJ, White LM, Bridges MD, Murphey MD, Peterson JJ, et al. Sclerosing variant of well-differentiated liposarcoma: relative prevalence and spectrum of CT and MRI features. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2013;201:154–61.

Acknowledgements

We thank Ms. Tomoyo Kakita for immunohistochemical staining, Mr. Motoyoshi Iwakoshi for slicing the tissue blocks, Ms. Miyuki Kogure for preparing the slides, and Dr. Yoshiya Sugiura and Dr. Rikuo Machinami for providing advice regarding the pathological diagnosis.

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

NI is the first author and YM is the corresponding author of this manuscript. SO participated in the operation of this case. HN and YI performed the pathological diagnosis and supervised the editing of the manuscript. NI and YM drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent for publication of this case was obtained from the patient.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Iwamoto, N., Matsuura, Y., Ninomiya, H. et al. An extremely rare case of rapidly growing mediastinal well-differentiated liposarcoma with a sclerosing variant: a case report. surg case rep 6, 158 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40792-020-00928-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40792-020-00928-4