Abstract

Background

Ruptured pseudoaneurysms are a rare complication of gastrectomy, but when they do develop, they are often fatal. We presented herein the first report of a case of pseudoaneurysm arising from the right inferior phrenic artery (RIPA) after a laparoscopic gastrectomy.

Case presentation

A 61-year-old male patient underwent a laparoscopic distal gastrectomy and D1+ lymph node dissection with Roux-en-Y reconstruction for early gastric cancer. He was discharged on postoperative day (POD) 9 without any complications, such as anastomotic or pancreatic leakage. On POD 19, he was referred to the emergency room for upper abdominal pain. Enhanced abdominal computed tomography revealed a 60 × 70 mm hematoma, indicating intra-abdominal bleeding and a 10-mm pseudoaneurysm in the RIPA. Selective digital subtraction angiography confirmed the presence of a pseudoaneurysm in the RIPA, which was embolized using multiple microcoils. Thereafter, no clinical signs were observed, and the patient was discharged from the hospital 15 days after angiography without any recurrence of bleeding. We hypothesized that the cause of the pseudoaneurysm was mechanical vascular injury due to the thermal spread of the ultrasonically activated devices (USADs) during lymphatic node dissection.

Conclusion

Given the thermal spread of USADs, safe and appropriate lymph node dissection based on precise anatomical knowledge is crucial to preventing postoperative pseudoaneurysms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Pseudoaneurysms result from the partial to complete disruption of the vascular wall and ultimately lead to hemorrhage contained by the adventitia of the vessel wall or the perivascular soft tissues [1]. Inferior phrenic artery (IPA) pseudoaneurysms are a very rare form of visceral pseudoaneurysm. Ruptured pseudoaneurysms are also a rare complication sometimes reported after a gastrectomy [2], but when they do develop, they are often fatal. We presented herein the first report of a case of a pseudoaneurysm arising in the right inferior phrenic artery (RIPA) after a laparoscopic gastrectomy.

Case report

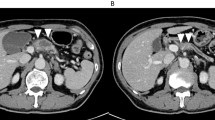

A 61-year-old male patient underwent a laparoscopic distal gastrectomy and D1+ lymph node dissection with Roux-en-Y reconstruction for early gastric cancer. He was discharged on postoperative day (POD) 9 without any complications, such as anastomotic or pancreatic leakage. On POD 19, he was referred to the emergency room for upper abdominal pain. Guarding and rebound tenderness were denied. Serum biochemistry showed a white blood cell count of 16.2 × 103/μL, red blood cell count of 396 × 104/μL, and hemoglobin 11.2 g/dL. Enhanced abdominal CT revealed a hematoma 60 × 70 mm in diameter, indicating intra-abdominal bleeding, and a 10-mm pseudoaneurysm in the RIPA (Fig. 1). A selective digital subtraction angiography confirmed the presence of a pseudoaneurysm in the RIPA (Fig. 2), which was cannulated and successfully embolized using multiple microcoils. After embolization, there were no clinical signs, and the patient was discharged from the hospital 15 days after the angiography without any recurrence of bleeding.

Discussion

Iatrogenic pseudoaneurysms can develop as a result of (a) mechanical vascular injury during the dissection or removal of lymph nodes and connective tissue due to a malignancy; (b) the digestion of the arterial vessels resulting from a pancreatic, biliary, or enteric fistula; or (c) local sepsis [3]. Pseudoaneurysms after abdominal surgery are a rare complication and most often occur after hepatobiliary pancreatic surgery. The development of pseudoaneurysms after gastric surgery is rare, with postoperative pseudoaneurysm hemorrhages developing in only 0.17% of patients undergoing a radical gastrectomy [2]. Pseudoaneurysms can be fatal; hence, early diagnosis and proper treatment are important to improve the prognosis. A falling hemoglobin level or a low-grade fever persisting for 2 to 3 weeks postoperatively should raise the suspicion of local sepsis with the potential for pseudoaneurysm development [4]. Recent interventional techniques using arterial embolization or stent grafts have been proposed as alternatives to surgical repair and offer real advantages in terms of survival [5].

In the present case, the RIPA pseudoaneurysm developed after a laparoscopic distal gastrectomy for gastric cancer. IPA pseudoaneurysms are very rare, with only nine cases (including our case) thus far reported (Table 1) [6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13]. Furthermore, IPA pseudoaneurysms after a gastrectomy are also extremely rare, with only two cases (including our case) reported to date. The present study is the first report of a case of ruptured RIPA pseudoaneurysm after a gastrectomy. In our case, the patient did not develop anastomotic leakage, pancreatic leakage, or intra-abdominal infection after surgery; we therefore assumed that the cause of the pseudoaneurysm was a mechanical vascular injury occurring during the dissection of the celiac artery lymph node (lymph node No.9), which is adjacent to the IPA and must be dissected via D1+ or D2 lymph node dissection in a gastrectomy for gastric cancer [14, 15].

In laparoscopic surgery, ultrasonically activated devices (USADs) are widely used for cutting, and when using USADs, precautions must be taken against lateral thermal damage to surrounding tissues that could lead to inadvertent trauma to the adjacent organs, including vessels [16]. When we reviewed the operation video, we did not observe any obvious mechanical damage to the RIPA but were unable to rule out potential damage to the RIPA due to the thermal spread of the USAD (Fig. 3). In retrospect, the following points can be adduced as possible causes of the pseudoaneurysm: (1) the flexible camera provided a very good surgical view which may have encouraged more extensive D1+ lymph node dissection than was necessary, thereby exposing the RIPA to damage; and (2) insufficient attention was given to the anatomical position of RIPA during the dissection of lymph node No.9. The RIPA is a thin vessel and difficult to recognize during lymph node dissection; therefore, the precise, preoperative localization of the RIPA is important during the dissection of lymph node No.9. The right and left IPA develop upward and laterally anterior to the crus of the diaphragm and terminate on the abdominal surface of the respective domes of the diaphragm [17]. Aslaner et al. reported that the right and left IPA were divided into two groups, those originating from a common trunk (29.5%) and those without a trunk having a different, independent origin (70.5%). In cases where IPA have a common trunk, the trunk originates from the aorta (16.4%), celiac artery (12.6%), renal artery (0.4%), or left gastric artery (0.1%). In cases where the RIPA and left IPA have disparate origins, the RIPA originates in the celiac artery (30.7%), aorta (25.2%), right renal artery (10.4%), left gastric artery (4.1%), or common hepatic artery (0.1%) [18]. In the present case, the RIPA originated from the aorta without a common trunk and ran close to the celiac artery and across and in front of the crus (Fig. 4). We surmised that in cases where the RIPA runs close to the vessels, such as the left gastric artery, common hepatic artery, or celiac artery, mechanical damage is likely to occur during lymph node dissection and lead to pseudoaneurysm development. Therefore, in these cases, closer attention should have been given to its position during dissection to avoid inflicting damage. After our experience with this case, we now routinely confirm the anatomy and direction of the RIPA on thin-section, arterial-phase dynamic CT.

Conclusions

We reported a case of RIPA pseudoaneurysm following a laparoscopic distal gastrectomy. Given the thermal spread of USADs, safe and appropriate lymph node dissection based on precise anatomical knowledge is important to prevent postoperative pseudoaneurysms.

Availability of data and materials

The data are not available for public access because of patient privacy concerns but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- RIPA:

-

Right inferior phrenic artery

- POD:

-

Postoperative day

- IPA:

-

Inferior phrenic artery

- USADs:

-

Ultrasonically activated devices

References

Núñez DB, Torres-León M, Múnera F. Vascular injuries of the neck and thoracic inlet: helical CT–angiographic correlation. Radiographics. 2004;24:1087–98.

Li Z, Jie Z, Liu Y, Xie X. Management of delayed hemorrhage following radical gastrectomy for gastric carcinoma patients. Hepatogastroenterology. 2012;59:2016–9.

Boufi M, Belmir H, Hartung O, Ramis O, Beyer L, Alimi YS. Emergency stent graft implantation for ruptured visceral artery pseudoaneurysm. J Vasc Surg. 2011;53:1625–31.

Cheung HYS, Tang CN, Fung KS, Li MKW. Bleeding pseudoaneurysms complicating upper abdominal surgery. HongKong Med J. 2007;13:449–52.

Tulsyan N, Kashyap VS, Greenberg RK, Sarac TP, Clair DG, Pierce G, et al. The endovascular management of visceral artery aneurysms and pseudoaneurysms. J Vasc Surg. 2007;45:276–83.

Shirai T, Amano J, Fujii N, Hirabayashi S, Suzuki A. Rupture of inferior phrenic artery aneurysm: an unusual complication of mesenteric arteritis due to postcoarctectomy syndrome. Chest. 1994;106:1290–1.

Toyoda H, Kumada T, Kiriyama S, Sone Y, Tanikawa M, Hisanaga Y, et al. Emergent transcatheter arterial embolization of ruptured inferior phrenic artery aneurysm with N-butyl cyanoacrylate. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2004;15:886–7.

Lee JW, Kim S, Kim CW, Kim KH, Jeon TY. Massive hemoperitoneum due to ruptured inferior phrenic artery pseudoaneurysm after blunt trauma. Emerg Radiol. 2006;13:147–9.

Harman A, Boyvat F, Hasdogan B, Aytekin C, Karakayali H, Haberal M. Endovascular treatment of active bleeding after liver transplant. Exp Clin Transplant. 2007;1:596–600.

Arora A, Tyagi P, Gupta A, Arora V, Sharma P, Kumar M, et al. Pseudoaneurysm of the inferior phrenic artery presenting as an upper gastrointestinal bleed by directly rupturing into the stomach in a patient with chronic pancreatitis. Ann Vasc Surg. 2012;26:860.e9.

Salem JF, Haydar A, Hallal A. Inferior phrenic artery pseudoaneurysm complicating drug-induced acute pancreatitis. BMJ Case Rep. 2014;2014:bcr2013201049.

Namikawa T, Kobayashi M, Hanazaki K. Transcatheter arterial embolization of ruptured inferior phrenic artery pseudoaneurysm following completion gastrectomy. J Gastrointest Surg. 2015;19:1561–2.

Gunjan D, Gamanagatti S, Garg P. Endoscopic ultrasonography-guided obliteration of a left inferior phrenic artery pseudoaneurysm in a patient with alcoholic chronic pancreatitis. Endoscopy. 2018;50:449–50.

Sano T, Kodera Y. Japanese gastric cancer treatment guidelines 2010 (ver. 3). Gastric Cancer. 2011;14:113–23.

Sano T, Kodera Y. Japanese classification of gastric carcinoma: 3rd English edition. Gastric Cancer. 2011;14:101–12.

Devassy R, Hanif S, Krentel H, Verhoeven HC, Torres-De la Roche LA, De Wilde RL. Laparoscopic ultrasonic dissectors: technology update by a review of literature. Med Devices Evid Res. 2019;12:1–7.

Agarwal S, Pangtey B, Vasudeva N. Unusual variation in the branching pattern of the celiac trunk and its embryological and clinical perspective. J Clin Diagnostic Res. 2016;10:AD05–7.

Aslaner R, Pekcevik Y, Sahin H, Toka O. Variations in the origin of inferior phrenic arteries and their relationship to celiac axis variations on CT angiography. Korean J Radiol. 2017;18:336–44.

Acknowledgements

None

Funding

None

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KI performed the surgery. KF and YI carried out the data acquisition and drafted the manuscript. SY, RY, FH, KI, and YM revised the article. All the authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The present study was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of our institution.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Funakoshi, K., Ishibashi, Y., Yoshimura, S. et al. Right inferior phrenic artery pseudoaneurysm after a laparoscopic gastrectomy: a case report. surg case rep 5, 187 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40792-019-0739-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40792-019-0739-x