Abstract

Background

Juvenile polyposis is an autosomal dominant inherited disease characterized by the development of numerous hamartomatous and nonneoplastic polyps of the gastrointestinal tract. Juvenile polyposis has also recently been reported as a predisposition for gastrointestinal cancer.

Case presentation

A 63-year-old man underwent esophagogastroduodenoscopy because of anemia and hypoalbuminemia during a follow-up for gastric polyposis, which showed multiple reddish polyps and two elevated lesions in the stomach. The elevated lesions were diagnosed as well-differentiated adenocarcinomas by biopsy. He had no specific physical findings or family history. Computed tomography showed gastric wall thickening without lymphadenopathy or distant metastasis. Colonoscopy showed an adenoma in the transverse colon. He underwent laparoscopy-assisted total gastrectomy with Roux-en-Y esophagojejunostomy. The resected specimen revealed numerous variously sized non-pedunculated polyps throughout the stomach, diagnosed histopathologically as hamartomatous polyps. The two elevated lesions were diagnosed as a well-differentiated adenocarcinoma restricted to the mucosa and a well-to-poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma invading the submucosa with prominent lymphatic permeation, respectively. Genetic analysis failed to identify any germline mutations in the genes usually associated with juvenile polyposis, including SMAD4 and BMPR1A. However, based on the few characteristic physical findings and histopathological features, the final diagnosis was juvenile polyposis restricted to the stomach.

Conclusions

This patient represented a rare case of non-familial juvenile polyposis of the stomach with gastric cancers. Juvenile polyposis has malignant potential, and patients should therefore be carefully followed up. Surgical treatment, particularly total gastrectomy, is recommended as a standard treatment in patients with juvenile polyposis of the stomach with gastric cancer.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Juvenile polyposis is a gastrointestinal polyposis characterized by the development of numerous hamartomatous and nonneoplastic polyps [1], with a prevalence of approximately one in 100,000–160,000 [2]. The most frequently affected site is the colorectum (98%), followed by the stomach (14%), jejunum and ileum (6.5%), and duodenum (2.3%) [3]. Juvenile polyposis limited to the stomach is very rare. Some patients have a family history of juvenile polyposis with an autosomal dominant pattern of inheritance, and SMAD4 and BMPR1A have recently been identified as causative genes for juvenile polyposis [4, 5]. Furthermore, although juvenile polyposis is generally recognized as a benign lesion, it has been associated with a predisposition to gastrointestinal cancer in some cases [6,7,8]. We report a very rare case of a patient with non-familial juvenile polyposis restricted to the stomach and gastric cancers, who was treated by laparoscopy-assisted total gastrectomy.

Case presentation

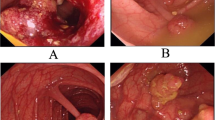

A 63-year-old man was evaluated for anemia (hemoglobin 11.8 g/dl) and hypoalbuminemia (albumin 3.7 g/dl) in another hospital. He had been diagnosed with gastric polyposis 5 years ago. He underwent esophagogastroduodenoscopy, which showed multiple reddish polyps accompanied by bleeding and erosion throughout the stomach (Fig. 1a) and two elevated lesions with irregular margins in the anterior wall of the corpus (Fig. 1b) and lesser curvature of the angular region (Fig. 1c) of the stomach. Histopathological diagnosis of the two elevated lesions by biopsy showed well-differentiated adenocarcinomas. He was referred to our hospital for treatment of gastric polyposis with gastric cancers. He had no medical history except for gastric polyposis, no family history, and no physical findings such as skin pigmentation or abnormalities of the hair and nails. Blood biochemical tests were negative for tumor markers (carcinoembryonic antigen, 0.6 ng/ml; carbohydrate antigen 19–9, 6.7 U/ml). Computed tomography showed gastric wall thickening, but no lymphadenopathy or distant metastasis. Colonoscopy showed only a polyp in the transverse colon, with a histopathological diagnosis of adenoma. The clinical stage was T1a N0 M0 stage IA according to the Japanese Gastric Cancer Association staging system (14th edition). He underwent laparoscopy-assisted total gastrectomy with D1+ dissection and Roux-en-Y esophagojejunostomy. The resected specimen revealed numerous small and large polyps throughout the stomach and two elevated lesions in the corpus and angular region, respectively (Fig. 2). Histopathological examination showed the polyps to comprise edematous lamina propria with hyperplastic foveolar epithelium and cystically dilated glands, indicating hamartomatous polyps (Fig. 3a, b). The elevated lesion in the corpus was a well-differentiated adenocarcinoma, restricted to the mucosa (Fig. 3a, c). The other elevated lesion in the angular region was a well-to-poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma invading the submucosa (Fig. 4a–c) with lymphatic permeation in the submucosa and muscularis propria detected by immunohistochemical staining with D2-40 (Fig. 4d). The carcinoma showed tubular formation in the mucosa (Fig. 4b), dedifferentiating gradually as it invaded the submucosa (Fig. 4c). Seven of 50 lymph nodes were metastasized by carcinoma cells, which was histopathologically similar to the primary tumor (no. 4d and 7). The final pathological stage was T2 N3 M0 stage IIIA. After receiving informed consent, we analyzed the patient’s genomic DNA to obtain a definitive diagnosis of hamartomatous polyposis. Genomic DNA was extracted from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded specimens of hamartomatous polyps and carcinoma, and target genes were comprehensively analyzed by next-generation sequencing with a multiple cancer-associated gene panel. The analysis identified somatic mutations in APC, KRAS, TP53, and ERBB2 genes in carcinoma, but failed to detect any germline mutations, including in SMAD4, BMPR1A, or PTEN, in hamartomatous polyps and carcinoma. However, based on the few characteristic physical findings and the histopathological features of the polyps, the final diagnosis was juvenile polyposis restricted to the stomach with gastric cancers. The patient was discharged on postoperative day 8 and has been monitored carefully with no adjuvant chemotherapy, by his request. There is no evidence of recurrence 16 months after surgery.

Endoscopic appearance of multiple reddish polyps accompanied by bleeding and erosion throughout the stomach (a). Elevated lesions with irregular margins in the anterior wall of the corpus (b) and lesser curvature of the angular region (c) of the stomach. Biopsy of the elevated lesions revealed them to be well-differentiated adenocarcinomas

Histopathological examination of the corpus region showed small and large polyps and one elevated lesion (a). The polyps comprised hyperplastic foveolar epithelium, cystically dilated glands, and edematous stroma accompanied by chronic inflammation, indicating hamartomatous polyps (b). The elevated lesion was diagnosed as a well-differentiated adenocarcinoma restricted to the mucosa, arising in the hamartomatous polyps (c). (a low-power view, b high-power view of square, × 2 objective lens; c high-power view of square, × 10 objective lens)

Histopathological examination of the angular region showed the other elevated lesion (a). The lesion was a well-differentiated adenocarcinoma in the mucosa (b), becoming more poorly differentiated as it invaded the submucosa (c). Prominent lymphatic permeation was detected by immunohistochemical staining with D2-40 (arrow) (d). (a low-power view, b high-power view of square, × 2 objective lens; c high-power view of square, × 10 objective lens; d high-power view, × 10 objective lens)

Discussion

Juvenile polyposis is a rare disease characterized by the development of numerous hamartomatous and nonneoplastic polyps throughout the gastrointestinal tract [1]. Diagnostic criteria of juvenile polyposis include the presence of more than five juvenile polyps in the colorectum, juvenile polyps throughout the gastrointestinal tract, and/or any number of juvenile polyps in a patient with a family history of juvenile polyposis [7]. Juvenile polyposis was reported in 1964 as multiple hamartomatous polyps throughout the intestine, with an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern [9], whereas juvenile polyposis restricted to the stomach was first reported in 1975 [6]. Juvenile polyposis is currently subdivided into three groups according to occurrence site: juvenile polyposis coli, gastric juvenile polyposis, and generalized juvenile polyposis [8, 10].

Hamartomatous polyposis syndrome of the gastrointestinal tract with autosomal dominant inheritance includes not only juvenile polyposis, but also Peutz–Jeghers syndrome and PTEN hamartoma tumor syndrome [11]. In addition, Cronkhite–Canada syndrome is a non-heritable disease that is also characterized by diffuse gastrointestinal polyps, which are histopathologically similar to hamartomatous polyps [12, 13]. Physical findings and family history are helpful for distinguishing between juvenile polyposis and other polyposis diseases. Patients with juvenile polyposis have few physical findings, such as cutaneous hyperpigmentation, dystrophic nail changes, and alopecia, which are detected in patients with Peutz–Jeghers or Cronkhite–Canada syndrome [14, 15]. In addition, patients with juvenile polyposis often show autosomal dominant inheritance, and about 75% of patients have a family history of juvenile polyposis [1]. Recent investigations reported SMAD4 [4] and BMPR1A [5] as genes responsible for juvenile polyposis. Both these genes encode proteins implicated in the transforming growth factor-β signaling pathway [16], which modulates various cellular processes including proliferation, differentiation, migration, adhesion, and death [17]. The prevalence of each of these germline mutations in juvenile polyposis is around 20% [2, 18], while the remaining patients have no such mutations. A confirmed diagnosis of juvenile polyposis is thus based not only on the histopathological features of the polyps, but also on the patient’s physical findings and family history, and on the presence of germline mutations in SMAD4 and BMPR1A. The current patient had no family history of juvenile polyposis or germline mutations in the SMAD4 and BMPR1A genes but was diagnosed with juvenile polyposis of the stomach based on physical findings and histopathological features. Case reports of non-familial juvenile polyposis published in PubMed from 1985 to 2017, including the present case (n = 12), are summarized in Table 1 [19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26]. In contrast to the current case, most previously reported patients were relatively young (4–18 years old) and the juvenile polyposis was restricted to the colon and/or rectum, with one case of a single polyp in the stomach [19]. The current case was thus a rare example of non-familial juvenile polyposis.

Although juvenile polyposis is a nonneoplastic lesion, several cases have suggested that it represents a predisposition to gastrointestinal cancer [6,7,8]. The risk of gastric cancer in patients with juvenile polyposis was reported to be approximately 11–21% [27], with a higher risk in patients with a SMAD4 germline mutation [28]. The current patient had no germline mutations of SMAD4 or BMPR1A, but did have somatic mutations in APC, KRAS, TP53, and ERBB2 genes. In addition, the histopathological findings showed a well-differentiated adenocarcinoma, or intestinal type according to the Lauren classification [29], directly arising in the hamartomatous polyps in the mucosa. These findings suggest that this case may be classified in the chromosomal instability group among the four molecular subtypes of gastric adenocarcinoma reported by the Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network, because this group was reported to show some salient features such as intestinal histology, TP53 mutation, and RTK-RAS activation [30].

Accordingly, patients with juvenile polyposis should undergo regular follow-ups, including gastrointestinal endoscopy, with surgical treatment in the event of gastric cancer. However, recurrences of gastric cancer and juvenile polyps in the remnant stomach have frequently been reported in patients who underwent partial gastrectomy [31, 32], and total gastrectomy should thus be considered in patients with juvenile polyposis of the stomach with gastric cancer.

Conclusions

We report a rare case of a patient with non-familial juvenile polyposis of the stomach with gastric cancers. This case highlights the malignant potential of juvenile polyposis and the need for careful follow-up of such patients. Total gastrectomy is recommended as a standard treatment in patients with juvenile polyposis of the stomach with gastric cancer.

References

Larsen Haidle J, Howe JR. In: Pagon RA, Adam MP, Ardinger HH, Wallace SE, Amemiya A, LJH B, Bird TD, Fong C, Mefford HC, RJH S, Stephens K, editors. Juvenile polyposis syndrome. Seattle: GeneReviews. University of Washington; 2003.

Chow E, Macrae F. A review of juvenile polyposis syndrome. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;20:1634–40.

Höfting I, Pott G, Schrameyer B, Stolte M. Familial juvenile polyposis with predominant stomach involvement. Z Gastroenterol. 1993;31:480–3.

Howe JR, Roth S, Ringold JC, Summers RW, Jarvinen HJ, Sistonen P, Tomlinson IP, Houlston RS, Bevan S, Mitros FA, Stone EM, Aaltonen LA. Mutations in the SMAD4/DPC4 gene in juvenile polyposis. Science. 1998;280:1086–8.

Howe JR, Bair JL, Sayed MG, Anderson ME, Mitros FA, Petersen GM, Velculescu VE, Traverso G, Vogelstein B. Germline mutations of the gene encoding bone morphogenetic protein receptor 1A in juvenile polyposis. Nat Genet. 2001;28:184–7.

Stemper TJ, Kent TH, Summers RW. Juvenile polyposis and gastrointestinal carcinoma: a study of a kindred. Ann Intern Med. 1975;83:639–46.

Jass JR, Williams CB, Bussey HJ, Morson BC. Juvenile polyposis - a precancerous condition. Histopathology. 1988;13:619–30.

Coburn MC, Pricolo VE, DeLuca FG, Bland KI. Malignant potential in intestinal juvenile polyposis syndromes. Ann Surg Oncol. 1995;2:386–91.

McColl I, Busxey HJ, Veale AM, Morson BC. Juvenile polyposis coli. Proc R Soc Med. 1964;57:896–7.

Agnifili A, Verzaro R, Gola P, Marino M, Mancini E, Carducci G, Ibi I, Valenti M. Juvenile polyposis: case report and assessment of the neoplastic risk in 271 patients reported in the literature. Dig Surg. 1999;16:161–6.

Zbuk KM, Eng C. Hamartomatous polyposis syndromes. Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;4:492–502.

Cronkhite LW, Canada WJ. Generalized gastrointestinal polyposis; an unusual syndrome of polyposis, pigmentation alopecia and onychotrophia. N Engl J Med. 1955;252:1011–5.

Burke AP, Sobin LH. The pathology of Cronkhite-Canada polyps. A comparison to juvenile polyposis. Am J Surg Pathol. 1989;13:940–6.

Tomlinson IP, Houlston RS. Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. J Med Genet. 1997;34:1007–11.

Daniel ES, Ludwig SL, Lewin KJ, Ruprecht RM, Rajacich GM, Schwabe AD. The Cronkhite-Canada syndrome. An analysis of clinical and pathologic features and therapy in 55 patients. Medicine (Baltimore). 1982;61:293–309.

Waite KA, Eng C. From developmental disorder to heritable cancer: it’s all in the BMP/TGF-beta family. Nat Rev Gene. 2003;4:763–73.

Wang J, Sun L, Myeroff L, Wang X, Gentry LE, Yang J, Liang J, Zborowska E, Markowitz S, Willson JK, Brattain MG. Demonstration that mutation of the type II transforming growth factor beta receptor inactivates its tumor suppressor activity in replication error-positive colon carcinoma cells. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:22044–9.

Howe JR, Sayed MG, Ahmed AF, Ringold J, Larsen-Haidle J, Merg A, Mitros FA, Vaccaro CA, Petersen GM, Giardiello FM, Tinley ST, Aaltonen LA, Lynch HT. The prevalence of MADH4 and BMPR1A mutations in juvenile polyposis and absence of BMPR2, BMPR1B, and ACVR1 mutations. J Med Genet. 2004;41:484–91.

Gilinsky NH, Elliot MS, Price SK, Wright JP. The nutritional consequences and neoplastic potential of juvenile polyposis coli. Dis Colon Rectum. 1986;29:417–20.

Panchagnula R, Kini U. Non familial juvenile polyposis presenting as chronic intestinal obstruction. J Assoc Physicians India. 2000;48:1020–1.

Bannura G, Soto D, Vial MT. Non familial juvenile multiple polyposis. A case report. Rev Med Chil. 2001;129:1065–70.

Okada T, Sasaki F, Ueki S, Nakagawa S, Kato M, Itoh T, Ota S, Todo S. Nonfamilial juvenile polyposis coli in a child: report of a case. Surg Today. 2004;34:609–12.

Chakraborty P, Shakuja P, Kundra A, Jain A, Singh S, Anuradha S, Agarwal A, Kar P. Non-familial juvenile polyposis with histological evidence of adenomatous transformation. Trop Gastroenterol. 2004;25:170–1.

Pratap A, Tiwari A, Sinha AK, Kumar A, Khaniya S, Agarwal RK, Shakya VC. Nonfamilial juvenile polyposis coli manifesting as massive lower gastrointestinal hemorrhage: report of two cases. Surg Today. 2007;37:46–9.

Tony J, Saji S, Sandesh K, Sunilkumar K, Ramachandran TM, Thomas V. Non-familial juvenile polyposis in prolapsed rectum. Trop Gastroenterol. 2007;28:129–30.

Ahmed A, Alsaleem B. Nonfamilial juvenile polyposis syndrome with exon 5 novel mutation in SMAD 4 gene. Case Rep Pediatr. 2017;2017:5321860. 10.1155/5321860

Ma C, Giardiello FM, Montgomery EA. Upper tract juvenile polyps in juvenile polyposis patients: dysplasia and malignancy are associated with foveolar, intestinal, and pyloric differentiation. Am J Surg Pathol. 2014;38:1618–26.

Aretz S, Stienen D, Uhlhaas S, Stolte M, Entius MM, Loff S, Back W, Kaufmann A, Keller KM, Blaas SH, Siebert R, Vogt S, Spranger S, Holinski-Feder E, Sunde L, Propping P, Friedl W. High proportion of large genomic deletions and a genotype phenotype update in 80 unrelated families with juvenile polyposis syndrome. J Med Genet. 2007;44:702–9.

Laurén P. The two histological main types of gastric carcinoma: diffuse and so-called intestinal-type carcinoma. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand. 1965;64:31–49.

The Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Comprehensive molecular characterization of gastric adenocarcinoma. Nature. 2014;513:202–9.

Hizawa K, Iida M, Yao T, Aoyagi K, Fujishima M. Juvenile polyposis of the stomach: clinicopathological features and its malignant potential. J Clin Pathol. 1997;50:771–4.

Ishida H, Ishibashi K, Iwama T. Malignant tumors associated with juvenile polyposis syndrome in Japan. Surg Today. 2018;48:253–63.

Acknowledgements

We thank Edanz Group Japan for editing a draft of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

TJ wrote the manuscript. EO supervised the manuscript. MN introduced the patient to our hospital. JK and EO performed the surgery. ST and MF diagnosed the histopathological findings. Other co-authors participated in the treatment of the patient and helped to draft the manuscript. EO, YO, and YM organized the writing of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The genetic analysis was approved by the ethics committee of Kyushu University (number 673-00), and written informed consent was obtained from the patient.

Consent for publication

When obtaining informed consent for the surgical procedure, general consent for publication and presentation was also obtained from the patient.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Jogo, T., Oki, E., Fujiwara, M. et al. Non-familial juvenile polyposis of the stomach with gastric cancers: a case report. surg case rep 4, 79 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40792-018-0488-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40792-018-0488-2