Abstract

Background

Imaging modalities (computed tomography (CT), ultrasonography, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)) have only limited ability to distinguish liver focal nodular hyperplasia (FNH) from metastatic liver tumors. Here, we report a patient who underwent surgery for benign FNH that mimicked a liver metastasis from soft tissue sarcoma (STS).

Case presentation

A 23-year-old man with a history of several surgeries for metastatic abdominal STS, developed a hepatic tumor accompanying peritoneal STS recurrence. He was diagnosed with a metastatic liver tumor from the STS, based on imaging studies for the hepatic tumor that showed a growing hypervascular lesion and hypo-intensity in hepatic phase on dynamic CT and MRI. However, when the liver and peritoneal tumors were resected, histological diagnosis showed the hepatic tumor to be benign liver FNH.

Conclusions

Although FNH should be considered as a differential diagnosis for hypervascular hepatic tumors, it has few typical findings, and its appropriate management is controversial. A lesion strongly suspected of being a metastatic liver tumor might require surgical resection.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Soft tissue sarcomas (STS) comprise a heterogeneous group of rare solid tumors. Although only a resection is needed for cure, intra-abdominal STS frequently recurs in the liver and peritoneum even after curative resection [1, 2]. For recurrent STS, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network guideline recommends surgery if the disease is resectable [3].

In contrast, surgery is not indicated for liver focal nodular hyperplasia (FNH) because it is a common and benign focal liver lesion [4, 5], and its natural history is typically uneventful [6]. However, several clinical cases have been surgically resected due to inaccurate diagnosis [7,8,9], mainly because differential diagnosis of FNH includes many kinds of hypervascular hepatic tumors. When a patient has other malignant disease, diagnosis of FNH can be even more complicated.

Here, we describe a patient with peritoneal recurrence of spindle cell sarcoma (SCS)—an unclassified STS—and FNH that was misdiagnosed as an STS metastasis to the liver.

Case presentation

A 23-year-old man had a history of two resections of SCS as the following clinical course.

At the initial resection at the age of 13, although the tumor was curatively resected, the SCS located on posterior layer of the rectus abdominis sheath was injured with the abdominal cavity exposed (Fig. 1a). Therefore, after his initial resection, he underwent adjuvant chemotherapy with cyclophosphamide, actinomycin-D and vincristine.

CT images for patient’s history of spindle cell sarcoma (SCS), originating from lower abdominal wall and 1st peritoneal recurrence after surgery. a Very large SCS stands out from lower abdominal wall (yellow arrow) when the patient was 13 years old. b Peritoneal recurrence of SCS on the mesentery over the small intestine (red arrow) when the patient was 22 years of age. Both lesions were curatively resected

At the age of 22, he was suffering from recurrence of the SCS besides the small intestine and was given curative resection (Fig. 1b). Histological examination of specimens showed an unclassified and intermediate grade SCS (Fig. 2a). Immunohistochemical findings showed the tumor cells to be positive for vimentin, TLE1, CD34, and EMA, and negative for desmin, myogenin, myoD1, SMA, CD117, S100, AE1/3, EMA, and ALK-1 (Fig. 2b). Furthermore, the fusion genes of rhabdomyosarcoma (PAX3–FKHR and PAX7–FKHR) were not detected on polymerase chain reaction-based method (data not shown).

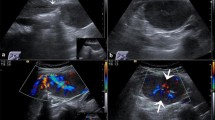

During the follow-up period, a solitary tumor in the lateral segment of the liver and two other tumors that are located beside the right kidney and on left anterior layer of the rectus abdominis sheath were newly diagnosed through contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CECT; Fig. 3a (liver tumor), Fig. 3b, c (small nodules)). The Gd ethoxybenzyl diethylenetriamine pentaacetic acid (Gd-EOB-DPTA)-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) for the hepatic tumor showed low intensity on T1-weighted image (WI) and slightly high intensity on T2WI, as a hypervascular lesion in dynamic study (Fig. 4a–c), and partly low-intensity area in the hepatocyte phase (Fig. 4d). The hepatic tumor almost doubled in diameter within 18 months (Fig. 5). Based on these results, the hepatic tumor was diagnosed as a liver metastasis of SCS. No abnormalities were observed in laboratory findings, including tumor makers (CEA, CA19-9, AFP, and PIVKA-II). Liver function was preserved, and hepatitis B surface antigen and hepatitis C antibody were both negative. Therefore, we performed a left liver lobectomy and curatively resected the two nodules in his abdomen. The operation took 391 min with 180 ml of blood loss. The postoperative course was favorable, and the patient was discharged on postoperative day 11. Histopathological examination showed recurrent SCS in the abdominal nodules (Fig. 6a); however, the hepatic tumor was diagnosed as benign FNH (Fig. 6b, c).

Liver tumor with intra-abdominal recurrence of spindle cell sarcoma. a Liver tumor is hyperdense during hepatic arterial phase (black arrow). b, c Two other disseminated nodules are shown beside the right kidney (b: yellow arrow) and on left anterior layer of the rectus abdominis sheath (c: red arrow)

Macroscopic and microscopic findings of resected specimens. a Two nodules in the abdomen showed metastatic soft tissue sarcoma, with small-nuclei spindle cells that grow invasively into adipose tissue. b, c The hepatic tumor contained b a small radiating scar, and c included large portal tracts and proliferated bile ducts

Discussion

Surgical resection can provide the potential for cure in patients with recurrence of STS. The local control rate at 5 years after resection was 85% [10]. In contrast, patients with unresectable lesion have poor prognosis. Reflecting these facts, patients with advanced tumor have poor prognosis: Five-year survival rates for stages I, II, and III are 98, 81, and 56%, respectively, according to the tumor, node, and metastasis stage grouping [11]. Therefore, adequate diagnosis of the recurrence and resection for selected patients are needed for treatment of STS.

As this patient had both recurrent SCS—an unclassified STS—and liver FNH, distinguishing the FNH from a hepatic metastasis was difficult. Other literature also reported some FNHs that were diagnosed as metastases in patients with concurrent malignancies, who therefore underwent resections, including two patients with insulinomas and one with renal cell carcinoma (Table 1) [8, 12, 13]. In these types of malignancy, surgery is recommended for recurrent disease, if complete resection is possible.

FNH typically shows a characteristic enhancement pattern on CT or MRI [14,15,16]: early nodular arterial enhancement and isodense appearance on portal venous phase [17]. Nevertheless, some FNHs show atypical imaging and are therefore difficult to diagnose accurately. The reported diagnostic ability in determining benign or malignant disease for CT scans is 78% specific [18] that of MRI is 96.6% sensitive and 87.6% specific [19]. To solve this problem, new modalities such as contrast-enhanced ultrasonography and shear-wave elastography [20] have been developed and assessed for diagnostic ability. However, about 10% of FNH are not accurately diagnosed preoperatively.

In the present case, a characteristic finding, such as a “central scar,” was not present. Also, in the MRI hepatobiliary phase, some atypical hemodynamic aberrations (such as the hypo-intense lesion with ring-like hyperintensity; Fig. 4d) suggested a metastatic liver tumor. Moreover, tumor growth during the observation period also suggested a malignant tumor, as FNHs rarely grow [21]. Mathieu et al. reported that tumor growth was observed in only 1.9% of FNH [6]. Thus, atypical imaging and tumor-like characteristics made accurate preoperative diagnosis difficult in this case.

Because the guideline offers no recommendation for preoperative histological diagnosis of resectable STS [2, 3], histological confirmation was not considered because surgery was the only curative treatment for SCS, and this patient had other peritoneal tumors that were highly suspected to be metastatic tumors.

Consequently, in the present case, surgical resection for liver tumors might be unnecessary according to the guideline [22]. Retrospectively, a preoperative histological confirmation for a hepatic lesion should have been performed. However, limited sampling size obtained with an aspiration biopsy might have also led to a misdiagnosis or to underestimating the malignancy [23, 24]. Therefore, a possibly malignant liver lesion should be resected. A conclusive preoperative diagnostic method for malignancy of liver tumors should be established; otherwise, clinicians should carefully consider the indication for surgery against the possibility of malignancy.

Conclusions

In conclusion, decisions for surgical resection should depend on details of the clinical situation, such as coexistence of malignancy or enlargement of FNH over time. However, a conclusive method for diagnosing FNH should be developed to avoid unnecessary surgery.

Abbreviations

- CECT:

-

Contrast-enhanced computed tomography

- FNH:

-

Focal nodular hyperplasia

- Gd-EOB-DPTA:

-

Gd ethoxybenzyl diethylenetriamine pentaacetic acid

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- SCS:

-

Spindle cell sarcoma

- STS:

-

Soft tissue sarcoma

References

Spillane AJ, Fisher C, Thomas JM. Myxoid liposarcoma—the frequency and the natural history of nonpulmonary soft tissue metastases. Ann Surg Oncol. 1999;6:389–94.

von Mehren M, Randall RL, Benjamin RS, Boles S, Bui MM, Conrad EU, et al. Soft tissue sarcoma, version 2.2016, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2016;14:758–86.

von Mehren M, Randall RL, Benjamin RS, Boles S, Bui MM, Casper ES, et al. Soft tissue sarcoma, version 2.2014. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2014;12:473–83.

Karhunen PJ. Benign hepatic tumours and tumour like conditions in men. J Clin Pathol. 1986;39:183–8.

Kaltenbach TE, Engler P, Kratzer W, Oeztuerk S, Seufferlein T, Haenle MM, et al. Prevalence of benign focal liver lesions: ultrasound investigation of 45,319 hospital patients. Abdom Radiol. 2016;41:25–32.

Mathieu D, Kobeiter H, Maison P, Rahmouni A, Cherqui D, Zafrani ES, et al. Oral contraceptive use and focal nodular hyperplasia of the liver. Gastroenterology. 2000;118:560–4.

Hashimoto K, Tatsumi N, Shimizu J, Nishida K, Nonaka R, Fujie Y, et al. Resected focal nodular hyperplasia that was difficult to differentiate from hepatocellular carcinoma—a case report (article in Japanese). Gan To Kagaku Ryoho. 2015;42:1869–71.

Jung SY, Kang B, Choi YM, Kim JM, Kim SK, Kwon YS, et al. Development of multifocal nodular lesions of a liver mimicking hepatic metastasis, following resection of an insulinoma in a child. Korean J Pediatr. 2015;58:69–72.

Chiorean L, Badea R, Dudea S, Chira O, Manole S, Caraiani C, et al. An atypical case of focal nodular hyperplasia. Problems of imagistic diagnosis. Med Ultrason. 2014;16:70–4.

Zagars GK, Ballo MT, Pisters PW, Pollock RE, Patel SR, Benjamin RS. Surgical margins and reresection in the management of patients with soft tissue sarcoma using conservative surgery and radiation therapy. Cancer. 2003;97:2544–53.

Edge S, Byrd DR, Compton CC, Fritz AG, Greene FK. American joint committee on cancer staging manual. New York: Springer; 2010. p. 291.

Jerraya H, Zidi-Mouaffek Y, Dokmak S, Dziri C. Insulinoma with focal hepatic lesions: malignant insulinoma? BMJ Case Rep. 2015. doi:10.1136/bcr-2015-212811.

Wheeler YY, Wheeler GL, Diaz-Arias AA, Anders RA. Metastatic renal cell carcinoma within a hepatic focal nodular hyperplasia: a case report and review of the literature. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2009;2:190–3.

Hussain SM, Terkivatan T, Zondervan PE, Lanjouw E, de Rave S, Ijzermans JN, et al. Focal nodular hyperplasia: findings at state-of-the-art MR imaging, US, CT, and pathologic analysis. Radiographics. 2004;24:3–17.

Zech CJ, Grazioli L, Breuer J, Reiser MF, Schoenberg SO. Diagnostic performance and description of morphological features of focal nodular hyperplasia in Gd-EOB-DTPA-enhanced liver magnetic resonance imaging: results of a multicenter trial. Invest Radiol. 2008;43:504–11.

Marin D, Brancatelli G, Federle MP, Lagalla R, Catalano C, Passariello R, et al. Focal nodular hyperplasia: typical and atypical MRI findings with emphasis on the use of contrast media. Clin Radiol. 2008;63:577–85.

Fowler KJ, Brown JJ, Narra VR. Magnetic resonance imaging of focal liver lesions: approach to imaging diagnosis. Hepatology. 2011;54:2227–37.

Procacci C, Fugazzola C, Cinquino M, Mangiante G, Zonta L, Andreis IA, et al. Contribution of CT to characterization of focal nodular hyperplasia of the liver. Gastrointest Radiol. 1992;17:63–73.

Morana G, Grazioli L, Kirchin MA, Bondioni MP, Faccioli N, Guarise A, et al. Solid hypervascular liver lesions: accurate identification of true benign lesions on enhanced dynamic and hepatobiliary phase magnetic resonance imaging after gadobenate dimeglumine administration. Invest Radiol. 2011;46:225–39.

Brunel T, Guibal A, Boularan C, Ducerf C, Mabrut JY, Bancel B, et al. Focal nodular hyperplasia and hepatocellular adenoma: the value of shear wave elastography for differential diagnosis. Eur J Radiol. 2015;84:2059–64.

Weimann A, Ringe B, Klempnauer J, Lamesch P, Gratz KF, Prokop M, et al. Benign liver tumors: differential diagnosis and indications for surgery. World J Surg. 1997;21:983–90.

European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines on the management of benign liver tumours. J Hepatol. 2016;65:386–98.

Belghiti J, Pateron D, Panis Y, Vilgrain V, Flejou JF, Benhamou JP, et al. Resection of presumed benign liver tumours. Br J Surg. 1993;80:380–3.

Lautz T, Tantemsapya N, Dzakovic A, Superina R. Focal nodular hyperplasia in children: clinical features and current management practice. J Pediatr Surg. 2010;45:1797–803.

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

The authors have no extra or intra-institutional funding to declare.

Authors’ contributions

MA described and designed the article. YF and SH supervised the writing of the manuscript. The other co-authors collected the data and discussed the content of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and its accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the editor-in-chief of this journal on request.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Amisaki, M., Honjo, S., Iida, N. et al. Focal nodular hyperplasia that mimicked a liver metastasis from a soft tissue sarcoma: a case report. surg case rep 3, 59 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40792-017-0332-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40792-017-0332-0