Abstract

Background

We conducted an economic assessment using test data from the phase III TRIPLE study, which examined the efficacy of a 5-hydroxytryptamine 3 receptor antagonist as part of a standard triplet antiemetic regimen including aprepitant and dexamethasone in preventing chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting in patients receiving cisplatin-based highly emetogenic chemotherapy (HEC).

Methods

We retrospectively investigated all medicines prescribed for antiemetic purposes within 120 h after the initiation of cisplatin administration during hospitalization. In the TRIPLE study, patients were assigned to treatment with granisetron (GRA) 1 mg (n = 413) or palonosetron (PALO) 0.75 mg (n = 414). The evaluation measure was the cost-effectiveness ratio (CER) assessed as the cost per complete response (CR; no vomiting/retching and no rescue medication). The analysis was conducted from the public healthcare payer’s perspective.

Results

The CR rates were 59.1% in the GRA group and 65.7% in the PALO group (P = 0.0539), and the total frequencies of rescue medication use for these groups were 717 (153/413 patients) and 573 (123/414 patients), respectively. In both groups, drugs with antidopaminergic effects were chosen as rescue medication in 86% of patients. The costs of including GRA and PALO in the standard triplet antiemetic regimen were 15,342.8 and 27,863.8 Japanese yen (JPY), respectively. In addition, the total costs of rescue medication use were 73,883.8 (range, 71,106.4–79,017.1) JPY for the GRA group and 59,292.7 (range, 57,707.5–60,972.8) JPY for the PALO group. The CERs (JPY/CR) were 26,263.4 and 42,628.6 for the GRA and PALO groups, respectively, and the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) between the groups was 189,171.6 (189,044.8–189,215.5) JPY/CR.

Conclusions

We found that PALO was more expensive than GRA in patients who received a cisplatin-based HEC regimen.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV) is an uncomfortable side effect that must be considered in patients with cancer. Prochlorperazine, high-dose metoclopramide, corticosteroids, and 5-hydroxytryptamine 3 (5-HT3) receptor antagonists (RAs) were demonstrated to significantly improve CINV symptoms within 24 h after the initiation of chemotherapy. Conversely, some patients experience CINV in the delayed phase [1].

Dopamine, serotonin, and substance P act as neurotransmitters for chemoreceptors. Aprepitant (APR), a neurokinin-1 (NK-1) RA, was developed in the 2000s (international birth date, March 2003) [2, 3]. Several reports discussed the cost-effectiveness of NK-1 RAs [4,5,6,7,8]. Meanwhile, current antiemetic guidelines recommend a three-drug combination consisting of a 5-HT3 RA, dexamethasone (DEX), and APR for patients receiving highly emetogenic chemotherapy (HEC) [9,10,11]. Palonosetron (PALO), a second-generation 5-HT3 RA with high binding affinity for the serotonin receptor that is expected to have antiemetic efficacy against delayed-phase CINV, reached the market during the same period as APR (international birth date, July 25, 2003) [12,13,14]. The PROTECT study conducted in Japan [15] verified the superiority of PALO, demonstrating that a regimen including a novel 5-HT3 RA, PALO, and DEX is better than the standard regimen of GRA and DEX in preventing CINV during the delayed phase in patients with cancer receiving HEC. However, APR could not be considered in this study because it had not been approved in Japan.

A randomized double-blind controlled trial (TRIPLE study [16]) was conducted to verify the prophylactic antiemetic effect of APR as part of a combination antiemetic regimen expected to be effective during the delayed phase of CINV. The primary endpoint of the TRIPLE study was a complete response (CR; no vomiting/retching and no rescue medication) within 120 h after the initiation of cisplatin treatment. Eligible patients were randomly allocated to double-blind treatment with either GRA (1 mg) or PALO (0.75 mg) as part of triplet antiemetic regimens for cisplatin-based HEC.

Although the primary endpoint was not met and the superiority of PALO was not demonstrated in this clinical trial (P = 0.0539), PALO displayed efficacy superior to GRA in terms of controlling CINV, especially in the delayed phase.

No previous study directly compared the cost-effectiveness of GRA and PALO, both in combination with APR and DEX, in preventing CINV in patients treated with cisplatin-based chemotherapy in terms of the detailed cost of antiemetics including rescue medication. As price information is available for all drugs covered by Japan’s health insurance program, it is possible to clarify the drug costs of antiemetics used by various patient groups and the cost-effectiveness ratio (CER) per instance of vomiting suppression as economic evidence. This research sought to clarify the cost-effectiveness of the triple antiemetic combinations and conduct real-world cost analysis using data from the TRIPLE study.

Methods

Patients

In total, 827 patients receiving cisplatin-based HEC enrolled in a randomized, double-blind, multicenter phase III trial to validate the superiority of PALO (0.75 mg) over GRA (1 mg) were evaluated. The study design details and primary results of our phase III trial were described previously [16].

This study was conducted in accordance with the Japanese Ethical Guidelines for Medical and Health Research Involving Human Subjects. The personal information of all subjects was deleted, and anonymized clinical data were analyzed retrospectively. In addition to the economic analysis of data from our phase III trial, we investigated and analyzed medical expenses based on data for receipt information during hospitalization in the Cancer Institute Hospital of the Japanese Foundation for Cancer Research after receiving approval from the clinical research ethics review committee.

Treatment

Patients with cisplatin-naive solid tumors were eligible for this economic analysis if they were scheduled to start their first cycle of chemotherapy including a cisplatin dose ≥50 mg/m2 upon hospital admission. Patients with previous cisplatin use could be enrolled if they received the drug > 3 months before enrollment. The inclusion and exclusion criteria were described previously [16].

All patients received GRA or PALO combined with APR and DEX. The standard prophylactic antiemetic regimen to be used during the first cycle of HEC consisted of intravenous PALO (0.75 mg) or GRA (1 mg) on day 1, in addition to oral APR (125 mg on day 1 and 80 mg/day on days 2–3) and intravenous DEX phosphate sodium (12 mg [equivalent to 9.9 mg of DEX] on day 1 and 8 mg/day [equivalent to 6.6 mg of DEX] on days 2–4). On day 1, patients received PALO or GRA together with DEX as an infusion over < 15 min starting at least 30 min before cisplatin was administered. Patients received APR at least 60 min before cisplatin was administered on day 1 and before breakfast on days 2–3.

Analysis method

Measurement of the effects of antiemetic therapy on nausea and vomiting

The CR rates in the TRIPLE study were 59.1% (244/413 patients) for the GRA group and 65.7% (272/414 patients) for the PALO group.

Regarding the case of CR or non-CR, we devised three categories according to the development of overall CINV as well as acute and delayed CINV (i.e.,., category 1, CR [0–120 h]; category 2, non-CR delayed; category 3, non-CR acute) and then retrospectively investigated the direct medical costs of antiemetics, the number of patients with vomiting, and the number of nausea episodes during the observation periods (Additional file 1: Fig. S1).

Drug cost of antiemetics

The cost of antiemetic drugs was calculated on the basis of the National Health Insurance drug price standard in 2012, during which the TRIPLE study was conducted, and considered the direct costs of medical care. Because generic alternatives were adopted in several institutions, we calculated the cost of treatment using the prices of both branded and generic drugs if the indication of both medicines was the same.

Study pharmacists and case report form (CRF)

All patients evaluated in this study were hospitalized during the 5-day period of observation. This minimized the effect of external factors on the onset of nausea and vomiting, such as carsickness or smell, for patients receiving chemotherapy. In the study, study pharmacists at each center who were blinded to treatment allocation evaluated the efficacy endpoints for each patient daily using diary and interview data to ensure a rigorous assessment of nausea and vomiting and rescue medication use. In this analysis, additional antiemetic usage (i.e., rescue medication) was investigated by collecting the actual usage data listed in the CRF of the TRIPLE study.

Regarding rescue medication, the intravenous solution was unified as 50 mL of normal saline to dissolve the rescue medication when an injection preparation was chosen, and the cost of the infusion was also added to the medical cost. The use of generic drugs was noted. In addition, in cases in which multiple dosage forms were distributed but dosage forms were not listed, they were recorded as the injection form and branded drug.

Calculation of the cost-effectiveness ratio (CER)

The mean cost per patient was calculated from the true cost of antiemetics used in each group. The CER was obtained by dividing the mean cost by the number of CRs. Meanwhile, the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) was calculated as the difference in mean cost between the groups divided by the difference in CR rates between the groups. In addition, the ICER range was calculated via a one-way sensitivity analysis of branded and generic drugs as rescue medication.

Analytical viewpoint and sensitivity analysis

The cost-effectiveness analysis was performed from the public healthcare payer’s perspective. The uncertainty of the results was explored via sensitivity analysis of uncertain factors. Because the adoption of antiemetics (i.e.,., branded or generic) differed among the institutions, we conducted one-way sensitivity analysis to calculate the drug cost for generic or branded drug use.

Cost of hospitalization according to the duration of treatment

To calculate the total medical cost of hospitalization related to chemotherapy including cisplatin and to clarify the actual cost of antiemetic medication, hospitalization expenses for 59 patients enrolled in the TRIPLE study at the Cancer Institute Hospital, Japanese Foundation for Cancer Research, were extracted and converted into a performance-based payment format using medical accounting cost data from the Diagnosis Procedure Combination database. Costs were investigated for both the total medical cost and the cost of drugs.

Results

Patient characteristics

In total, 827 patients (414 in the PALO group and 413 in the GRA group) were evaluated for efficacy at 20 Japanese institutions between July 2011 and June 2012 in the TRIPLE study, and all patients were included in this economic analysis. The baseline characteristics of patients in each treatment group are summarized in Table 1. All baseline demographic parameters were similar between the groups.

Drug cost of antiemetics

One tablet of lorazepam 0.5 mg, which was the least expensive generic benzodiazepine, cost only 5 Japanese yen (JPY), whereas one ampoule of palonosetron hydrochloride injection 0.75 mg (branded medicine), the most expensive medicine, cost 14,522 JPY. The second most expensive medicine was a tri-pack of APR (branded medicine, 11,244.8 JPY). The costs of standard prophylactic antiemetic treatment were 15,342.8 JPY for the GRA group and 27,863.8 JPY for the PALO group, producing a difference of 12,521 JPY. The prices of drugs used as antiemetics to prevent CINV are presented in Additional file 2: Table S1.

In addition, the medical cost of antiemetics based on the revision of the National Health Insurance drug price standard in 2016 is presented in Additional file 3: Table S2 (rate: 1 US dollar = 110.57 JPY, 1 euro = 128.85 JPY, July. 4, 2018).

Effectiveness and incidence of CINV

CR rates during the 120-h period after the initiation of the first cycle of cisplatin treatment were 59.1% in the GRA group and 65.7% in the PALO group (P = 0.0539).

Vomiting within 120 h after cisplatin administration during hospitalization occurred in 75 patients (18.2%) in the GRA group and 65 patients (15.7%) in the PALO group. The total frequencies of nausea during the observation period were 1092 and 887 in the GRA and PALO groups, respectively. Vomiting, nausea, and rescue medication use were less frequent in the PALO group, whereas the CINV-preventive effect was superior for GRA (Table 2).

In addition, the proportion of patients with vomiting was higher in the acute phase (category 3) of non-CR based on the CR judgment than in the delayed phase (category 2).

Rescue medication

The total frequencies of rescue medication use within 120 h after cisplatin administration during hospitalization were 717 (153/413 patients) in the GRA group and 573 (123/414 patients) in the PALO group. The total additional costs for rescue medication use were 73,883.8 and 59,292.7 JPY in the GRA and PALO groups, respectively.

In addition, the ranges of additional expenses calculated by one-way sensitivity analysis to determine drug costs in cases of generic (minimum) or branded (maximum) drugs were 71,106.4–79,017.1 JPY for the GRA group and 57,707.5–60,972.8 JPY for the PALO group (Table 2). The mean additional expense of rescue medication use was higher in category 3 than in category 2.

Antiemetics selected as rescue medication

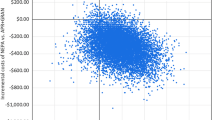

Antidopaminergic agents (metoclopramide, domperidone, and prochlorperazine maleate) were selected as medication for CINV for 86% of patients in each treatment group (Fig. 1).

Antiemetics selected as rescue medication. The total frequencies of rescue medication use within 120 h after cisplatin administration during hospitalization were 717 (153/413 patients) in the granisetron (GRA) group and 573 (123/414 patients) in the palonosetron (PALO) group. Antidopaminergic agents (metoclopramide, domperidone, and prochlorperazine maleate) were used as rescue medication for CINV in 86% of patients in each treatment group

The usage of other medicines (i.e., benzodiazepine compound, corticosteroids, antihistamines) was also similar between the groups. Olanzapine was used 7 (0.96%) and 11 times (1.91%) in the GRA and PALO groups, respectively.

The cost-effectiveness ratio

The CERs for the GRA and PALO groups were 26,263.4 and 42,628.6 JPY/CR, respectively (Table 2). The ICER required to achieve the observed difference in overall phase CR rates between the two treatment groups of 6.6% in favor of the PALO group was 189,171.6 JPY/CR. The range of the ICER estimated via our one-way sensitivity analysis was 189,044.8–189,215.5 JPY/CR.

Cost of hospitalization over duration of treatment

We also conducted medical expenses analysis based on the data for receipt information during hospitalization in the Cancer Institute Hospital of the Japanese Foundation for Cancer Research. The cost data before 2011 on this facility had become unavailable by refurbishing the medical computer system, and accordingly among 59 patients enrolled in the TRIPLE study were used the data of 43 patients. The results of our retrospective survey are shown in Table 3.

The mean medical cost (SD) during hospitalization related to cancer chemotherapy was 1,113,138.8 (870,137.9) JPY, including a drug cost of 195,716.7 (152,411.2) JPY. The total medical costs were 1,199,584.35 (1,043,255.9) JPY in the GRA group (n = 23) and 1,013,726.5 (627,690.9) JPY in the PALO group (n = 20). In addition, the drug costs in these groups were 227,712.6 (189,732.7) and 158,921.5 (83,676.9) JPY, respectively. Meanwhile, costs related to antiemetic prophylaxis and added rescue medication use were higher in the PALO group.

Discussion

We conducted this economic analysis to obtain economic evidence without using a simulation model in addition to clinical evidence of the efficacy of standard triplet antiemetic therapy in the TRIPLE study [16].

From this economic evaluation, we determined the CER and ICER, which served as indices of the cost-effectiveness of standard triplet antiemetic therapy for preventing CINV in patients receiving cisplatin-based HEC regimens in Japan. We expect that these indices will lead to the generation of highly transparent evidence for comparing the cost-effectiveness of novel antiemetics developed in the near future. For example, the usefulness of olanzapine for preventing chemotherapy-induced nausea was recently reported [17], and our indices can evaluate whether new standard prophylactic antiemetic regimens using olanzapine have additional effects corresponding to the cost of HEC. Moreover, it appears useful to identify individual drug interactions associated with APR, especially strategies for patients with limited steroid use [18,19,20] and combinations of inexpensive antiemetics.

Although the TRIPLE study was a randomized controlled trial, the eligibility criteria for the study were relatively similar to clinical practice guidelines, and patient registration in the study was not influenced by life-related prognostic factors that verify the effect of chemotherapy; thus, the results of this economic study approximately could be considered real-world data.

In addition, the protocol of the TRIPLE study stipulated that a branded medicine (granisetron 1 mg) was the standard triplet antiemetic in a prophylactic regimen. Because generic drugs are recommended in clinical practice, it is considered that the ICER will further increase due to increased generic drug use.

The difference in the incremental drug cost per patient and cycle for antiemetic prophylaxis in the two treatment groups was 12,521 JPY in favor of GRA. Conversely, the average additional costs for rescue medication use were 178.9 JPY in the GRA group and 143.2 JPY in the PALO group. The cost difference of the standard triplet prophylaxis regimen was approximately 350 times larger than that of the average additional cost for rescue medication, reflecting the high cost of PALO. Furthermore, the range of the ICER calculated from the one-way sensitivity analysis was 189,044.8–189,215.5 JPY/CR, indicating that the influence of rescue medication use on treatment costs is small. Recently published literature using a simulation model revealed that PALO 0.25 mg was not more cost-effective than GRA 3 mg for patients following HEC in an economic evaluation of a 5-HT3 RA and DEX without APR [21]. Our economic study indicated that the difference in price between PALO 0.75 mg and GRA 1 mg was large and that it is the factor most strongly affecting the ICER. Thus, this economic evaluation also revealed that PALO 0.75 mg was more expensive than GRA 1 mg in patients receiving cisplatin-based HEC, in line with a previous report [21].

A national policy is required to suppress soaring medical costs in Japan, and a basic policy to drastically reform the National Health Insurance drug price list has been planned ahead of the introduction of expensive and innovative new medicines [22]. The formal introduction of a cost-effectiveness evaluation is being discussed. In addition, “Guidelines for economic evaluation of healthcare technologies in Japan [23]” have been developed; therefore, there are few reports of economic evaluations in the country. Although one report raised questions regarding pharmacoeconomic evaluations based on randomized controlled trials [24], an urgent need for treatment options based on the efficient use of medical resources and cost-effectiveness exists. Therefore, it is expected that the availability of economic evidence in clinical practice based on real-world cost analyses will be promoted mainly by clinical trial planners, and it is desirable to actively publicize this information [25, 26].

The major limitation of this retrospective research was that it could not track the influence of repeat chemotherapy administration and the additional use of antiemetics to prevent anticipatory CINV, because this study was just focused on the effect of antiemetics within 120 h of the first cycle of cisplatin administration, which is extremely short term. In addition, the other limitation of this research was that this research was a CRF-based analysis limited to the cost of antiemetic drugs during the 5-day observation period. Although it is necessary to analysis excessive cost of prolonged hospitalization to identify better strategy for CINV prevention, we could not conduct such data analysis with available CRF. Therefore, it is possible to confirm the robustness of our results by implementing a simulation model using quality-adjusted life years as a complementary study of cost-effectiveness or conducting a retrospective investigation to clarify the influence of treatment continuation in trial-registered patients on the prognosis of antiemetic therapy.

Antiemetic therapy, a preventive strategy for CINV, should be selected considering for cost-effectiveness and individualization. This retrospective research revealed that GRA was more cost-effective than PALO in patients receiving cisplatin-based HEC regimens. In addition, Tsuji et al. conducted that the risk factor analysis [27] and gene polymorphism research [28] revealed evidence such as predictive factor as a follow-up research of the TRIPLE study. We should verify that predicting patients who should use PALO or patients who can obtain sufficient effect even with combinations of inexpensive antiemetics before treatment of chemotherapy.

Further investigation demonstrated that the minimum and maximum total medical and drug costs differ by more than 10-fold. The high costs were attributed to pemetrexed use (high drug cost) and pharyngeal cancer (high cost of medical examinations). This suggests that the expense of anticancer drugs, which are more expensive than antiemetics, is attracting attention in practical medical care.

Conclusions

We determined the CER and ICER, which served as indices of the cost-effectiveness of standard triplet antiemetic therapy for preventing CINV in patients receiving cisplatin-based HEC regimens in Japan. Also, we found that PALO 0.75 mg was more expensive than GRA 1 mg in the patients who received the cisplatin-based HEC regimen.

Abbreviations

- APR:

-

Aprepitant

- CC:

-

Complete Control

- CDDP:

-

Cisplatin

- CER:

-

Cost-Effectiveness Ratio

- CINV:

-

Chemotherapy-Induced Nausea and Vomiting

- CR:

-

Complete Response

- CRF:

-

Case Report Form

- DEX:

-

Dexamethasone

- GRA:

-

Granisetron

- HEC:

-

highly emetogenic chemotherapy

- ICER:

-

Incrimental Cost-Effectiveness Ratio

- JPY:

-

Japanease yen

- PALO:

-

Palonosetron

- QALYs:

-

Quality-adjusted Life years

- TC:

-

Total Control

References

Tamura K, Aiba K, Saeki T, Nakanishi Y, Kamura T, Baba H, Yoshida K, Yamamoto N, Kitagawa Y, Maehara Y, Shimokawa M, Hirata K, Kitajima M. CINV study Group of Japan: testing the effectiveness of antiemetic guidelines: results of a prospective registry by the CINV study Group of Japan. Int J Clin Oncol. 2015;20:855–65.

Hesketh PJ, Bohlke K, Lyman GH, Basch E, Chesney M, Clark-Snow R, Danso MA, Jordan K, Somerfield MR, Kris MG. The oral neurokinin-1 antagonist aprepitant for the prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: a multinational, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in patients receiving high-dose cisplatin--the Aprepitant protocol 052 study group. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:4112–9.

Poli-Bigelli S, Rodrigues-Pereira J, Carides AD, Julie Ma G, Eldridge K, Hipple A, Evans JK, Horgan KJ, Lawson F. Aprepitant protocol 054 study group: addition of the neurokinin 1 receptor antagonist aprepitant to standard antiemetic therapy improves control of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. Results from a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in Latin America. Cancer. 2003;97:3090–8.

Moore S, Tumeh J, Wojtanowski S, Flowers C. Cost-effectiveness of aprepitant for the prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting associated with highly emetogenic chemotherapy. Value Health. 2007;10:23–31.

Annemans L, Strens D, Lox E, Petit C, Malonne H. Cost-effectiveness analysis of aprepitant in the prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting in Belgium. Support Care Cancer. 2008;16:905–15.

Humphreys S, Pellissier J, Jones A. Cost-effectiveness of an aprepitant regimen for prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting in patients with breast cancer in the UK. Cancer Manag Res. 2013;5:215–24.

Chan SL, Jen J, Burke T, Pellissier J. Economic analysis of aprepitant-containing regimen to prevent chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting in patients receiving highly emetogenic chemotherapy in Hong Kong. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol. 2014;10:80–91.

Lordick F, Ehlken B, Ihbe-Heffinger A, Berger K, Krobot KJ, Pellissier J, Davies G, Deuson R. Health outcomes and cost-effectiveness of aprepitant in outpatients receiving antiemetic prophylaxis for highly emetogenic chemotherapy in Germany. Eur J Cancer. 2007;43:299–307.

Basch E, Prestrud AA, Hesketh PJ, Kris MG, Feyer PC, Somerfield MR, Chesney M, Clark-Snow R, Flaherty AM, Freundlich B, Morrow G, Rao KV, Schwartz, Rowena N, Lyman GH. Antiemetics: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline update. JCO. 2011;29:4189–98.

MASCC/ESMO Antiemetic Guideline 2016. https://www.mascc.org/2016-mascc-esmo-antiemetic-https://www.mascc.org/2016-mascc-esmo-antiemeticguidelines. (Accessed Nov 2018)

NCCN clinical practice guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines®) for antiemesis V.1.2017. https://www.nccn.org/patients/guidelines/nausea/files/.../nausea.pdf. (Accessed Nov 2018).

Gralla R, Lichinitser M, Van Der Vegt S, Sleeboom H, Mezger J, Peschel C, Tonini G, Labianca R, Macciocchi A, Aapro M. Palonosetron improves prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting following moderately emetogenic chemotherapy: results of a double-blind randomized phase III trial comparing single doses of palonosetron with ondansetron. Ann Oncol. 2003;14:1570–7.

Maemondo M, Masuda N, Sekine I, Kubota K, Segawa Y, Shibuya M, Imamura F, Katakami N, Hida T, Takeo S. PALO Japanese cooperative study group: a phase II study of palonosetron combined with dexamethasone to prevent nausea and vomiting induced by highly emetogenic chemotherapy. Ann Oncol. 2009;20:1860–6.

Popovic M, Warr DG, Deangelis C, Tsao M, Chan KK, Poon M, Yip C, Pulenzas N, Lam H, Zhang L, Chow E. Efficacy and safety of palonosetron for the prophylaxis of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV): a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Support Care Cancer. 2014;22:1685–97.

Saito M, Aogi K, Sekine I, Yoshizawa H, Yanagita Y, Sakai H, Inoue K, Kitagawa C, Ogura T, Mitsuhashi S. Palonosetron plus dexamethasone versus granisetron plus dexamethasone for prevention of nausea and vomiting during chemotherapy: a double-blind, double-dummy, randomised, comparative phase III trial. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:115–24.

Suzuki K, Yamanaka T, Hashimoto H, Shimada Y, Arata K, Matsui R, Goto K, Takiguchi T, Ohyanagi F, Kogure Y, Nogami N, Nakao M, Takeda K, Azuma K, Nagase S, Hayashi T, Fujiwara K, Shimada T, Seki N, Yamamoto N. Randomized, double-blind, phase III trial of palonosetron versus granisetron in the triplet regimen for preventing chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting after highly emetogenic chemotherapy: TRIPLE study. Ann Oncol. 2016;27:1601–6.

Navari RM, Qin R, Ruddy KJ, Liu H, Powell SF, Bajaj M, Dietrich L, Biggs D, Lafky JM, Loprinzi CL. Olanzapine for the prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:134–42.

Aapro MS, Walko CM. Aprepitant: drug-drug interactions in perspective. Ann Oncol. 2010;21:2316–23.

Celio L, Frustaci S, Denaro A, Buonadonna A, Ardizzoia A, Piazza E, Fabi A, Capobianco AM, Isa L, Cavanna L, Bertolini A, Bichisao E, Bajetta E. Italian trials in medical oncology group: Palonosetron in combination with 1-day versus 3-day dexamethasone for prevention of nausea and vomiting following moderately emetogenic chemotherapy: a randomized, multicenter, phase III trial. Support Care Cancer. 2011;19:1217–25.

Komatsu Y, Okita K, Yuki S, Furuhata T, Fukushima H, Masuko H, Kawamoto Y, Isobe H, Miyagishima T, Sasaki K, Nakamura M, Ohsaki Y, Nakajima J, Tateyama M, Eto K, Minami S, Yokoyama R, Iwanaga I, Shibuya H, Kudo M, Oba K, Takahashi Y. Open-label, randomized, comparative, phase III study on effects of reducing steroid use in combination with Palonosetron. Cancer Sci. 2015;106:891–5.

Du Q, Zhai Q, Zhu B, Xu XL, Yu B. Economic evaluation of 5-HT3 receptor antagonists in combination with dexamethasone for the prevention of 'overall' nausea and vomiting following highly emetogenic chemotherapy in Chinese adult patients. J Oncol Pharm Pract. 2016.

Council on Economic and Fiscal Policy, Cabinet Office, Japan. http://www5.cao.go.jp/keizai-shimon/kaigi/minutes/2016/1125/gijiyoushi.pdf. (Accessed Nov 2018).

Guideline for economic evaluation of healthcare technologies in Japan. https://www.mhlw.go.jp/file/05-Shingikai-12404000-Hokenkyoku-Iryouka/0000033418.pdf. (Accessed Nov 2018).

Sculpher MJ, Claxton K, Drummond M, McCabe C. Whither trial-based economic evaluation for health care decision making? Health Econ. 2006;15:677–87.

Garrison LP Jr, Neumann PJ, Erickson P. Using real-world data for coverage and payment decisions. The ISPOR real-world data task force report. Value Health. 2007;10:326–35.

Berger ML, Martin BC, Husereau D. A questionnaire to assess the relevance and credibility of observational studies to inform health care decision making: an ISPOR-AMCP-NPC good practice task force report. Value Health. 2014:143–56.

Yokoi M, Tsuji D, Suzuki K, Kawasaki Y, Nakao M, Ayuhara H, Kogure Y, Shibata K, Hayashi T, Hirai K, Inoue K, Hama T, Takeda K, Nishio M, Itoh K. Genetic risk factors for chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting in patients with cancer receiving cisplatin-based chemotherapy. Suppor Caer Cancer. 2018;26:1505–13.

Tsuji D, Yokoi M, Suzuki K, Daimon T, Nakao M, Ayuhara H, Kogure Y, Shibata K, Hayashi T, Hirai K, Inoue K, Hama T, Takeda K, Nishio M, Itoh K. Influence of ABCB1 and ABCG2 polymorphisms on the antiemetic efficacy in patients with cancer receiving cisplatin-based chemotherapy: a TRIPLE pharmacogenomics study. The Pharmacogenomics J. 2017;17:435–40.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

There was no specific funding for this study.

Availability of data and materials

KS had full access to all the actual usage data listed in the case report form of the TRIPLE study. The data has already been anonymized and personal information has been deleted. The other authors do not own the data.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HS, KS, TU, SI and NI contributed to the retrospective study conception and design. DT, TY, HH, KG, RM, NS, T Shimada, TH, NY and T Sasaki participated in the study design. HS, TU, and TH were involved in data acquisition. KS had full access to all the data in the TRIPLE phase III trial and takes full responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. HS, KS, TU, SI and NI were involved in data analysis and interpretation. HS drafted the manuscript and revised it critically for important intellectual content. DT and T Sasaki helped to draft the manuscript and revise it. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Authors’ information

HS, RPh.: Pharmacist at Showa University Hospital; KS, RPh. Ph.D.: Pharmacist at Cancer Institute Hospital, Japanese Foundation for Cancer Research; TU, RPh. Ph.D.: Pharmacist at Showa University Hospital; DT, Ph.D.: Pharmacist at School of Pharmaceutical Sciences, University of Shizuoka; TY, M.D. Ph.D.: Statistician at Yokohama City University; HH, RPh.: Pharmacist at National Cancer Center Hospital; KG, M.D. Ph.D.: Doctor at National Cancer Center Hospital East; RM, RPh.: Pharmacist at National Cancer Center Hospital East; NS, M.D. Ph.D.: Doctor at Teikyo University School of Medicine; T Shimada, RPh.: Pharmacist at Teikyo University Hospital; SI, M.D. Ph.D.: Doctor at International University of Health and Welfare; NI, M.D. Ph.D.: Doctor at St Luke’s International University; TH, RPh. Ph.D.: Pharmacist at Cancer Institute Hospital, Japanese Foundation for Cancer Research; NY, M.D. Ph.D.: Doctor at Wakayama Medical University; T Sasaki, RPh. Ph.D.: Pharmacist at Showa University Hospital.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors have no conflicts of interest directly relevant to the content of this article.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

Figure S1. The structure of the category and effect measurement of CINV. The CR rates in the TRIPLE study were 59.1% (244/413 patients) for the GRA group and 65.7% (272/414 patients) for the PALO group. Regarding the case of CR or non-CR, we devised three categories according to the development of overall CINV as well as acute and delayed CINV (category 1, CR [0–120 h]; category 2, non-CR delayed; category 3, non-CR acute). (PPTX 83 kb)

Additional file 2:

Table S1. Drug cost of antiemetics. (XLS 15 kb)

Additional file 3:

Table S2. Drug cost of antiemetics on the National Health Insurance drug price standard in 2017. (XLS 18 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Shimizu, H., Suzuki, K., Uchikura, T. et al. Economic analysis of palonosetron versus granisetron in the standard triplet regimen for preventing chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting in patients receiving highly emetogenic chemotherapy in Japan (TRIPLE phase III trial). J Pharm Health Care Sci 4, 31 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40780-018-0128-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40780-018-0128-9