Abstract

Background

We newly proposed that “Furuta method,” a pharmacist intervention guidelines, is a topical ointment therapy that considers the physical properties and moist environment of wounds for pressure ulcer (PU) treatment. The aim of this multicenter retrospective study was to investigate the effectiveness of this method for PU.

Methods

A total of 888 consecutive patients who underwent treatment for PU at 37 hospitals and five dispensing pharmacies in Japan between August 2010 and July 2014 were included in the study. Based on a survey on compliance to “Furuta method,” single-blind allocation was conducted into compliance (n = 437) and non-compliance (n = 451) groups, followed by a retrospective data collection. The primary and secondary outcomes were the healing period and rates of unhealed wounds, respectively. Data was expressed as mean ± standard deviation. Two-sided log rank tests were used for between-group comparisons of PU progression, whereas Kaplan–Meier plots were used for comparison between groups. We performed rigorous adjustment for marked differences in baseline patient characteristics by propensity score (PS) matching.

Results

After PS matching, patients were categorized as DESIGN-R d2 (n = 202), D3 (n = 130), D4 and 5 (n = 76), and DU (n = 76). In terms of the healing period, the patients in the compliance groups healed faster than those in the non-compliance groups in d2 (23.6 ± 36.8 vs. 32.2 ± 16.6 days; P < 0.001), D3 (46.8 ± 245.5 vs.137.3 ± 52.7 days; P < 0.001), and D4, 5 (122.5 ± 225.7 vs. 258.2 ± 292.7 days; P < 0.001). There were significantly lesser events of PU progression in the compliance group than in the non-compliance group (15 vs. 54; P = 0.003).

Conclusions

“Furuta method” is the new therapeutic strategy of PU, a pharmacist intervention guidelines, may possibly increase healing rates of PUs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Pressure ulcers (PUs) may develop when persistent pressure on bony prominences obstructs a healthy capillary flow, leading to tissue necrosis [1]. The primary cause of PUs is ischemic changes induced by pressure-related external forces, including shear force [2], and it is a common complication of immobility among the elderly [3]. Moreover, the elderly are at a high risk of developing PU because of immobility [4, 5], poor nutritional status [6, 7], and decreased body weight [5]. Despite recent research developments in the process of wound healing, treatment strategies for pressure ulcers remain inconclusive [8]. PU is a major contributor to an impaired quality of life by increasing mortality and the length of stay, burdening healthcare systems [9, 10].

An important factor in treatment resistance is the undermining formation, commonly observed in deep PUs [11]. Treatment-resistant PUs may be associated with changes in physical wound properties because of aging, such as mobility and deformity [12], and the high incidence of the undermining formation in PUs over the sacrum, coccyx, and greater trochanter [13]. Evaluation of wound deformity and mobility has been shown to improve healing following topical ointment therapy [14]; moreover, an active control of topical ointment application has been demonstrated to be important for moist wound healing in PUs [15].

In Japan, PUs have been treated by a team comprising physicians, pharmacists, and nurses, based on physical properties of the wound and using topical ointment for moist wound healing. Thus, this concept has been shown to be therapeutically effective at an improved medical cost [16]. Further, it has been spreading to pharmacists in Japan. However, there have been no detailed descriptions of interventions by pharmacists for PU treatment. Based on this background, we newly proposed the concept of topical ointment therapy by pharmacists, called “Furuta method” (Appendix), for PU, considering the physical properties and moist environment of wounds, and we promote widespread training sessions according to Furuta method in Japan. The aim of this study was to investigate the effectiveness of PU therapeutic effects treated by trained pharmacist according to “Furuta method” in Japan and to compare the results based on the compliance surveys of this “Furuta method.”

Methods

Setting

The study was based on compliance surveys and retrospective data collection from 37 hospitals and five dispensing pharmacies in Japan. Hospitals and dispensing pharmacies were appealed to participate via the “decunet” mailing list used by pharmacists involved in PU. Pharmacists who participated in this study underwent training sessions according to “Furuta method” in Japan. We set the suitable standards for the PU team, which comprised physicians, pharmacists, nurses, and other medical staff. Data of the National Center for Geriatrics and Gerontology (NCGG) were excluded because Furuta was involved in PU treatment. Finally, 35 hospitals and four pharmacies were included. All researchers collected data in a severely managed the personal information. The study protocol was approved by the ethics committee of NCGG.

Compliance survey

For compliance confirmation of pharmacist intervention guidelines on PU topical ointment therapy called “Furuta methods” (see Appendix), a self-administered 10-item questionnaire including the questions was provided: 1. are you treating PU more than once a week?; 2. do you assess the wound using descriptive ulcer dermatology?; 3. do you assess ointment base properties?; 4. do you assess wound surface moisture and use the Expert Furuta Blend ointment?; 5. do you assess the physical properties of the wound?; 6. do you treat the wound using wound fixation?; 7. do you assess the wound surface and edge?; 8. do you control the moisture of the wound by assessing granulation tissue deformation by an external force?; 9. do you assess external forces applied to the wound and treat by wound fixation?; and 10. do you assess residual tissue, such as the dermis, subcutaneous tissue, and fascia? This questionnaire was completed by responding yes (1 point) or no (0 point). This questionnaire was a single-blind method, which allocated patients to the compliance (≥8 points) and non-compliance (<8 points) groups. This was followed by a retrospective data collection.

Patients

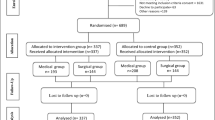

A total of 888 consecutive patients who underwent PU treatment in Japan between August 2010 and July 2014 were enrolled in this study (Fig. 1). Only patients who met the following criteria were included: (a) patients whose diagnosis were assigned as DESIGN-R [17] ≥ d2; (b) patients who received intervention from the PU team for ≥7 days during the observational period. Patient with missing information on the following data were excluded from this study: age, sex, hemoglobin, serum albumin, site of PU, DESIGN-R score, and observation period. Thus, a total of 868 patients were included; the mean patient age was 80.0 ± 11.3 years (standard deviation, Table 1).

Propensity score matching

To reduce treatment-selection bias and potential confounding variables, we performed rigorous adjustment for marked differences in baseline patient characteristics with propensity score (PS) matching using the following algorithm: 1:1 optimal match with a ±0.03 caliper and no replacement. Possible confounders were selected based on clinical knowledge for their potential association with the outcome of interest. The PS model was estimated using a logistic regression model that adjusted for patient characteristics, such as age, sex, hemoglobin, albumin, DESIGN-R score at baseline, and observation period. To measure covariate balance, an absolute standardized difference above 10 % represented meaningful imbalance [18, 19].

Study variables and statistical analysis

The main outcome was a comparison of healing days, which was calculated based on a previous study [20] that used the following equation:

DESIGN-R was used for monitoring of PU healing progression and is defined by the following components: depth, exudate, size, inflammation/infection, granulation tissue, necrotic tissue, and pocket [17]. The secondary endpoint was rates of unhealed wound.

Data were presented as mean ± standard deviation. Paired comparisons were performed using paired t-test for categorical variables and Mann–Whitney U test for continuous variables. Kaplan–Meier plots were created for evaluating the study endpoints, and the respective 95 % CI values were calculated. For the Kaplan–Meier plot for PU progression, all patients were included except for healed cases. Moreover, two-sided log rank tests were used for between-group comparisons of PU progression. All analyses were performed using SPSS version 22.0 software (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA). A two-tailed P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

The mean compliance survey point was 7.3 ± 2.8, and results were collected from 19 (437 patients) and 20 (451 patients) facilities. In the questions 2, the compliance rate based on descriptive ulcer dermatology was the lowest.

Based on the DESIGN-R criteria, 343 patients were diagnosed as d2, 220 as D3, 159 as D4, 5, and 146 patients as DU (Table 1). Individuals who did and did not undergo treatment based on “Furuta method” differed for all measured characteristics.

Table 2 shows the detailed characteristics of patients included in the final analysis: d2 (n = 202); D3 (n = 130); D4, 5 (n = 76); and DU (n = 76). The covariate balance in the matched cohort considerably improved. In Fig. 2, for each DESIGN-R group of patients, the respective duration of healing was significantly shorter in the compliance group than in the non-compliance group: d2 (23.6 ± 36.8 vs. 32.2 ± 16.6 days; P < 0.001); D3 (46.8 ± 245.5 vs. 137.3 ± 52.7 days; P < 0.001); D4, 5 (122.5 ± 225.7 vs. 258.2 ± 92.7 days; P < 0.001); and DU (78.1 ± 298.9 vs. 142.5 ± 79.4 days; P < 0.001). Moreover, wound healing was significantly different among the DESIGN-R groups (P < 0.001, data not shown).

Figure 3 shows the Kaplan–Meier plot for PU progression, according to the DESIGN-R score. The number of cases with PU progression was significantly lesser in the compliance group (n = 92) than in the non-compliance group (n =157) (15 vs. 54, respectively; P = 0.003; Fig. 3).

Discussion

The results of our study demonstrate that “Furuta method,” was effective for PU treatment in terms of early complete recovery and prevention of PU progression. However, there is a need for aggressive pharmacist intervention while using this method. It is important to conduct simultaneous prevention and treatment for PU; in this study, it is noteworthy that the compliance group did not deteriorate. Pharmacists who participated in this study, result of trained workshop according to Furuta methods, more improved assessment of topical ointment therapy considering the external force for PUs were compared with similar factors in the non-compliance group.

In a previous report conducted at NCGG, treatment periods according to National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel (NPUAP) stage definitions were 10 ± 6 days for Stage II, 43 ± 17 days for Stage III, and 80 ± 32 days for Stage IV [20]. In our study, the mean duration of healing in the compliance group was 23.6 ± 36.8 days in patients with d2, 46.8 ± 245.5 days in patients with D3, and 122.5 ± 225.7 days in patients with D4 and D5. In a previous study, only NCGG data (based on “Furuta method”), encompassed a wide range of treatment periods that was comparable with the present study. We believe the low compliance observed with “Furuta method” may be influenced by the treatment period. Further, the compliance rate with descriptive ulcer dermatology was the lowest, and this pathological assessment was not routinely performed by general healthcare workers. It is necessary to educate pharmacists and general healthcare workers regarding these techniques. A randomized single-blind controlled trial reported 8-week healing rates for Stage II ulcers of only 50 % in both groups [21]. Moreover, Horn et al. reported treatment failure rates for Stage III and IV ulcers of 90 % at 8 weeks [22]. These reports mainly investigated dressing therapy for PU and did not evaluate wound assessment according to wound physical properties and descriptive ulcer dermatology. It has been proposed that topical ointment therapy according to Furuta methods had a greater efficacy than dressing therapy.

Furthermore, in this study, there were significantly fewer cases of PU progression in the compliance group than in the non-compliance group (15 vs. 54; P = 0.003). Thus, we believe that an appropriate wound assessment according to “Furuta method” has utility in preventative management.

This study has several limitations. First, it is a retrospective, albeit multicenter, study; hence, there is a potential for bias. This was minimized by performing PS matching, which has been previously shown to be useful [23]. Second, this study did not consider the involvement of the nutritionist and physical therapist. Therefore, prospective trials that consider these other factors are necessary in the future.

Conclusion

We introduce a concept of PU topical ointment therapy, called “Furuta method,” which considers the physical properties and moist environment of wounds and pharmacist intervention guidelines and may be aided by pharmacist participation. This method may possibly lead to an increase in PU healing rates.

References

Lyder CH. Pressure ulcer prevention and management. JAMA. 2003;289(2):223–6.

Mustoe T. Understanding chronic wounds: a unifying hypothesis on their pathogenesis and implications for therapy. Am J Surg. 2004;5A:65S–70. United States.

Allman R. Pressure ulcers among the elderly. N Engl J Med. 1989;320(13):850.

Baumgarten M, Margolis DJ, Localio AR, Kagan SH, Lowe RA, Kinosian B, et al. Pressure ulcers among elderly patients early in the hospital stay. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2006;61(7):749–54.

Allman RM, Goode PS, Patrick MM, Burst N, Bartolucci AA. Pressure ulcer risk factors among hospitalized patients with activity limitation. JAMA. 1995;273(11):865–70.

Thomas DR. The role of nutrition in prevention and healing of pressure ulcers. Clin Geriatr Med. 1997;13(3):497–511.

Stratton RJ, Ek A-C, Engfer M, Moore Z, Rigby P, Wolfe R, et al. Enteral nutritional support in prevention and treatment of pressure ulcers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing Res Rev. 2005;4(3):422–50.

Smith ME, Totten A, Hickam DH, Fu R, Wasson N, Rahman B, et al. Pressure ulcer treatment strategies: a systematic comparative effectiveness review. Ann Intern Med. 2013;159(1):39–50.

Landi F, Onder G, Russo A, Bernabei R. Pressure ulcer and mortality in frail elderly people living in community. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2007;44 Suppl 1:217–23.

Bennett G, Dealey C, Posnett J. The cost of pressure ulcers in the UK. Age Ageing. 2004;33(3):230–5.

Ohura Takehiko ON. Pathogenetic mechanisms and classification of undermining in pressure ulcers elucidation of relationship with deep tissue injuries. Wounds. 2006;2006(18):329.

Mizokami F, Furuta K, Utani A, Isogai Z. Definitions of the physical properties of pressure ulcers and characterisation of their regional variance. Int Wound J. 2013;10(5):606–11.

Takahashi Y, Isogai Z, Mizokami F, Furuta K, Nemoto T, Kanoh H, et al. Location-dependent depth and undermining formation of pressure ulcers. J Tissue Viability. 2013;22(3):63–7.

Mizokami F, Furuta K, Matsumoto H, Utani A, Isogai Z. Letter: Sacral pressure ulcer successfully treated with traction, resulting in a reduction of wound deformity. Int Wound J. 2014;11(1):106–7.

Katsunori F. Strategies of pressure ulcer treatment by topical ointement therapy. Jpn J PU. 2014;16(2):115–21.

Katsunori F, Fumihiro M, Tetsuya M, Taku M, Osamu N, Minoru N, et al. Effects of pressure ulcer treatment teams including physicians, pharmacists, and nurses on medical costs. J Jpn Soc Healthc Admin. 2013;50(3):199–207.

Matsui Y, Furue M, Sanada H, Tachibana T, Nakayama T, Sugama J, et al. Development of the DESIGN-R with an observational study: an absolute evaluation tool for monitoring pressure ulcer wound healing. Wound Repair Regen. 2011;19(3):309–15.

Austin PC. Propensity-score matching in the cardiovascular surgery literature from 2004 to 2006: a systematic review and suggestions for improvement. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2007;134(5):1128–35. e3.

Austin PC. An introduction to propensity score methods for reducing the effects of confounding in observational studies. Multivariate Behav Res. 2011;46(3):399–424.

Mizokami F, Katsunori F, Noda Y, Zenzo I. Pharmacist should lead to appropriate pressure ulcer treatment for elderly patient. J Jpn Soc Hosp Pharm. 2010;46(12):1643–6.

Graumlich JF, Blough LS, McLaughlin RG, Milbrandt JC, Calderon CL, Agha SA, et al. Healing pressure ulcers with collagen or hydrocolloid: a randomized, controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51(2):147–54.

Bergstrom N, Horn SD, Smout RJ, Bender SA, Ferguson ML, Taler G, et al. The National Pressure Ulcer Long-Term Care Study: outcomes of pressure ulcer treatments in long-term care. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(10):1721–9.

Strasak AM, Zaman Q, Marinell G, Pfeiffer KP, Ulmer H. The use of statistics in medical research. The American Statistician. 2007;61(1):47–55.

Nagai Y, Isogai Z, Furuta K, Ishikawa O. Establishment of descriptive ulcer dermatology for pressure ulcer. Jpn J PU. 2009;11(2):105–11.

Mizokami F, Takahashi Y, Nemoto T, Nagai Y, Tanaka M, Utani A et al. Wound fixation for pressure ulcers: A new therapeutic concept based on the physical properties of wounds. J Tissue Viability. 2015;24(1):35–40.

Noda Y, Fujii S. Critical role of water diffusion into matrix in external use iodine preparations. Int J Pharm. 2010;394(1–2):85–91.

Tsuboi R, Tanaka M, Kadono T, Nagai Y, Furuta K, Noda Y, et al. JSPU Guidelines for the Prevention and Management of Pressure Ulcers (3rd Ed.). Jpn J PU. 2014;16(1):12–90.

Furuta K. Strategies of pressure ulcer treatment by topical ointment therapy. Jpn J PU. 2014;16(2):115–21.

Acknowledgment

We appreciate the following members of the participating hospitals and pharmacies: Aiko Tsuda, Akihiro Manaka, Ayano Murakawa, Chikatsugu Tsuchida, Erena Tasaki, Etsuko Fukuzawa, Ginji Fukazawa, Hideaki Shimoda, Hiroko Tsuchiya, Hiroatu Kadowaki, Junko Harayama, Kahori Kato, Kaoru Hirose, Koji Muto, Machiko Koike, Mami Yuza, Mari Sadaoka, Masako Hasegawa, Emi Umemura, Michiko Sakai, Miki Kawasaki, Mina Uozumi, Minoru Nagata, Naoko Yoshii, Norie Tsuboi, Osamu Nagata, Reiko Araki, Reiko Inagaki, Rie Shoji, Shigeki Ikushima, Syuichi Nakai, Masashi Saiga, Takehiko Tezuka, Taku Morikawa, Tetsuya Miyagawa, Tomoyasu Watanabe, Yoko Mogi, Yoko Nohara, Yoshihiro Kawade, Yoshihiro Kondo, Yoshio Tachibana, Miyuki Nakura, Yuji Iizuka, Yuri Hikida, Yusuke Sekine, and Yuto Tsume.

We appreciate valuable comments on our manuscript received from Tomohiro Mizuno.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

This study was funded by Research on Regulatory Science of Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices from Health Labour Sciences Research Grant in Japan. The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Authors’ contributions

KF and FM wrote the manuscript, performed the statistical analyses, and conducted data interpretation. HS and MY provided interpretation and discussion of the data. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Appendix

Appendix

Pharmacist intervention guidelines on pressure ulcer topical ointment therapy “Furuta method”

Wound assessment

It is desirable to examine the wound at least once a week based on descriptive ulcer dermatology [24].

-

1)

Wound physical property [12]: Assess by wound mobility and deformity. Wound mobility is the movement of the wound from the bony prominence, whereas wound deformity is a change in the three-dimensional shape of the wound and can result in undermining formation, a characteristic of deep pressure ulcers. Layered granulation tissue arising from wound deformity attenuates topical ointment therapy.

-

2)

Wound fixation [25]: Wound fixation is defined as alleviation of wound deformity by exogenous materials. It is classified as traction, anchor, and insertion. Wound fixation by traction is performed using an elastic bandage. Wound fixation by anchor also alleviates direct pressure on the wound using sponge (Reston™, Sumitomo 3 M, Tokyo, Japan or Prosoft™, NICHIBAN, Tokyo, Japan). Wound fixation by insertion is usually performed using materials of an appropriate hardness and absorbability, such as chitin cotton and alginate foam. For each case, the external force of the pressure ulcer was evaluated in order to select the appropriate wound fixation method.

-

3)

Residual tissue [24]: To evaluate and eliminate necrosis in residual tissue, such as the dermis, subcutaneous tissue, and fascia. However, physical properties of the wound are stabilized in the dermis.

-

4)

Wound surface and edge: To evaluate the several properties of the wound surface and edge, such as edematous, sclerotic, dry, glossy, or hemorrhagic granulation tissue; flat with smooth edge sunken with smooth edge or sunken with indented edge; and fibrin-coated film. Based on the evaluation of the wound surface and edge, the moisture of the wound was controlled by the characteristics of the ointment base (active or passive absorption) [26].

-

5)

Granulation tissue: The granulation tissue is deformed by an external force. Edematous granulation tissue formation by an external force is necessary to consider the measures of preventing the cause of the external force. Based on the evaluation of the granulation tissue, the moisture of the wound was controlled using characteristics of the ointment base (active or passive absorption) [26], and the external force was controlled by wound fixation [25].

-

6)

Pocket: A wound pocket is mainly formed by an external force. Based on the evaluation of the external force on the pocket, the moisture of the wound was controlled using characteristics of the ointment base (active or passive absorption) [26], and the external force was controlled by wound fixation [25].

Topical agent assessment

The selection of a topical ointment was based on the “Japanese society of pressure ulcers Guidelines for the Prevention and Management of Pressure Ulcers” [27]. As necessary, wound assessment based on descriptive ulcer dermatology [24] considered the use of Expert Furuta Blend Ointment [28]. Exudate formation in the wound was confirmed by checking the top dressing and gauze.

-

1)

Shallow pressure ulcer

-

1.

Inflammation and infection: Povidone–iodine sugar ointment, dextranomer beads, cadexomer iodine beads, iodine–potassium iodide gel, and iodoform gauze

-

2.

Necrotic tissue

Under the wound surface moisture: silver sulfadiazine cream, and iodoform gauze with saline

Over the wound surface moisture: iodoform gauze and bromelain ointment

-

3.

Epithelialization

Under the wound surface moisture: lysozyme hydrochloride ointment with sulfadiazine ointment (3:7), bucladesine sodium ointment, alprostadil alfadex ointment, trafermin splay, lysozyme hydrochloride ointment with iodine gel (1:1), and hydrocolloid dressing

Over the wound surface moisture: povidone–iodine sugar ointment and urethane foam dressing

-

1.

-

2)

Deep pressure ulcer

-

1)

Inflammation and infection: povidone–iodine sugar ointment, dextranomer beads, cadexomer iodine beads, iodine–potassium iodide gel, and iodoform gauze

-

2.

Necrotic tissue

Surgical debridement for black necrotic tissue

Under the wound surface moisture: silver sulfadiazine cream and iodoform gauze with saline.

Over the wound surface moisture: iodoform gauze, bromelain ointment, povidone–iodine sugar ointment, dextranomer beads, cadexomer iodine beads, and iodine–potassium iodide gel

-

1)

-

3)

Formation of granulation tissue

Edematous granulation tissue: povidone–iodine sugar ointment, povidone–iodine sugar ointment with dextranomer beads (4:1), and tretinoin tocoferil ointment with dextranomer beads (3:2)

Dry granulation tissue: tretinoin tocoferil ointment, trafermin spray, povidone–iodine sugar ointment with tretinoin tocoferil ointment (3:1), tretinoin tocoferil ointment with sulfadiazine ointment (3:7), and tretinoin tocoferil ointment with dextranomer beads (3:2)

-

4)

Epithelialization

Under wound surface moisture: lysozyme hydrochloride ointment with sulfadiazine ointment (3:7), bucladesine sodium ointment, alprostadil alfadex ointment, trafermin spray, lysozyme hydrochloride ointment with iodine gel (1:1), and hydrocolloid dressing

Over the wound surface moisture: povidone–iodine sugar ointment, and urethane foam dressing

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Furuta, K., Mizokami, F., Sasaki, H. et al. Active topical therapy by “Furuta method” for effective pressure ulcer treatment: a retrospective study. J Pharm Health Care Sci 1, 21 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40780-015-0021-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40780-015-0021-8