Abstract

Introduction

Dental implants have become a standard treatment in the replacement of missing teeth. After tooth extraction and implant placement, resorption of buccal bundle bone can pose a significant complication with often very negative cosmetic impacts. Studies have shown that if the dental root remains in the alveolar process, bundle bone resorption is very minimal. However, to date, the deliberate retention of roots to preserve bone has not been routinely used in dental implantology.

Material and methods

This study aims to collect and evaluate the present knowledge with regard to the socket-shield technique as described by Hurzeler et al. (J Clin Periodontol 37(9):855-62, 2010). A PubMed database search (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed) was conducted to identify relevant publication.

Results

The initial database search returned 229 results. After screening the abstracts, 13 articles were downloaded and further scrutinised. Twelve studies were found to meet the inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Conclusion

Whilst the socket-shield technique potentially offers promising outcomes, reducing the need for invasive bone grafts around implants in the aesthetic zone, clinical data to support this is very limited. The limited data available is compromised by a lack of well-designed prospective randomised controlled studies. The existing case reports are of very limited scientific value. Retrospective studies exist in limited numbers but are of inconsistent design. At this stage, it is unclear whether the socket-shield technique will provide a stable long-time outcome.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

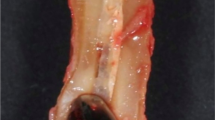

Dental implants have become a standard treatment in the replacement of missing teeth. Whilst initially dental implants were mainly used to secure complex multi-unit prostheses, in recent decades, it has become common to replace single teeth, in particular in the aesthetic zone. Paired with the ever increasing demand to achieve cosmetically pleasing outcomes, this has led to the demand to preserve buccal hard and soft tissues. After tooth extraction and implant placement, resorption of buccal bundle bone can pose a significant complication with often very negative cosmetic impacts. Hence, grafting procedures are commonly carried out with the intention of minimising loss of bundle bone. However, if it proved possible to preserve bundle bone, these graft procedures might not be necessary. Studies have shown that if the dental root remains in the alveolar process, bundle bone resorption is very minimal. Knowing this, the technique of retaining roots has long been utilised for cases involving removable prostheses, and to a lesser degree, fixed prostheses. However, to date, the deliberate retention of roots to preserve bone has not been routinely used in dental implantology. Back as early as 2010, Hurzeler et al. published a proof of concept proposing partial retention of tooth roots in an effort to preserve the important buccal bone. Preservation of bone and ossification between residual roots and surrounding bone have been demonstrated in beagle dogs [1] (Fig. 1a–d histology of socket-shield in beagle dogs).

Hurzeler et al. postulated that leaving a 1.5-mm-thick root fragment on the buccal aspect of the proposed implant site [1] would leave sufficient space for optimal placement of the dental implant as well as maintain the buccal plate.

Figures 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, and 13 illustrate the socket-shield technique as per Hurzeler et al.

In addition to the beagle dog histology provided by Hurzeler [1], Schwimer et al. [2] provided human histology showing bone formation between the remaining dentin of the socket shield and the implant surface. Whilst this histology was made possible due to a failed implant, it needs to be noted that this was an unintentional socket shield, and hence socket-shield dimensions as well as height reduction might have been less than desirable with regard to the here described socket-shield technique and therefore contributed to the implant failure.

This literature review examines the available evidence regarding the socket-shield technique as postulated by Prof. Hurzeler.

A recently published systematic review [3] concluded that modifications to the socket-shield technique as postulated by recent studies was associated with promising results. Furthermore, it was stated that the choice of graft materials for socket-shield application did not play much of a role. However, data presented in the review by Mourya et al. does not seem to either confirm or oppose this statement. Therefore this critical review was conducted.

Material and methods

Study procedure and material

This study aims to collect and evaluate the present knowledge with regard to the socket-shield technique as described by Hurzeler et al. [1].

The following inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied:

Inclusion criteria:

-

Studies including case reports investigating the socket-shield technique

-

Studies published in English

-

Studies published between January 01, 1990, and May 12, 2019

Exclusion criteria:

-

Animal studies

-

In vitro studies

-

Literature reviews

-

Studies published in languages other than English

Search strategy

This literature review was performed accordingly to the PRISMA 2009 checklist.

A PubMed database search (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed) was conducted to identify relevant publication.

The following search term including Boolean operators was used:

(dental AND ((implant OR implants) AND ((socket shield OR socket-shield OR root membrane OR Huerzeler OR partial extraction therapy))). This returned 288 positive results, all abstracts were scrutinised, and articles found to meet the inclusion and exclusion criteria were downloaded for further investigation and screened by both authors independently.

Furthermore, the bibliographies of all downloaded articles were screened manually to identify further relevant studies.

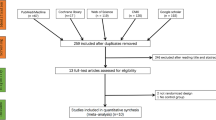

In addition, a Google Scholar search with the identical search phrase was conducted to identify further potentially relevant articles. Studies found in addition to the PubMed database search were labelled hand search (Fig. 14).

Data extraction

Data pertinent to the use of the socket-shield technique was extracted and entered into the master table (Table 1).

Results

The initial database search returned 229 results. After screening the abstracts, 23 articles were downloaded and further scrutinised. Twelve studies were found to meet the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The reference lists were further subjected to a hand search which returned a further 6 studies for this literature review (Fig. 14).

The studies included are summarised in Table 1.

General overview

Hurzeler et al. published the first article on the socket-shield technique [1]. Since then, the amount of publications has steadily increased, with the largest number of publication in 2018 (Table 2). Most publications were case reports; however, retrospective studies have been published as early as 2014. Retrospective studies make up the minority of data published (Table 3). Prospective studies have not been cited to date.

Type of publications

The majority of publications identified in this literature review were case reports (16/24) [1, 5,6,7, 9,10,11, 13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23, 25,26,27]. Three publications were retrospective clinical trials/studies [8, 12, 24]; one publication was a randomised clinical trial [4].

Cohort size

The cohort size did vary considerably, whilst the majority of case reports reported on single clinical cases up to 3 cases. The three retrospective clinical trials did report on as many as 128 cases followed up [12] and as little as 10 [8].

Only one randomised clinical trial was identified in this literature review [4] with a total of 40 implants in 40 patients and a follow-up period of 36 months.

Observation time

The observation time reported did vary considerably from 0 months up to 9 years [20]. The majority of publications however did not state observation times past 1 year.

Outcome

All studies reported on osseointegration of implants and reported osseointegration rates comparable to traditional placement protocols. Generally, the case reports identified in this literature review reported an osseointegration rate of 100%. However, both referred to retrospective clinical trials (Gluckman et al. [12], Siormpas et al. [24]) reporting significantly lower osseointegration rates of 96.1% and 87.9%.

The only randomised clinical trial (Bramanti et al. [4]) identified on the other hand reported 100% osseointegration; however, the cohort size was only 40 implants for both test and study group combined.

Six studies did report additional to this regarding the cosmetic outcome [8, 10, 12, 23].

Several studies/case reports reported on the cosmetic outcome of the implant treatment; however, the cosmetic outcome was not consistently evaluated, one study used the pink aesthetic score, one study simply mentioned the positive outcome, and one study employed volumetric measurements to disciple the amount of tissue remodelling [25].

Preservation of buccal architecture/bone-height

Almost all of the studies presented reported on the preservation of the alveolar ridge and/or soft tissue buccal to the implant [1, 4, 5, 7, 8, 10,11,12,13,14, 16, 17, 19, 22, 23, 25, 26].

However, the reporting was inconsistent with regard to how this outcome was measured.

Three studies analysed the volumetric changes by means of 3-dimensional scans [7, 8, 23], one study evaluated the buccal bone by means of taking post-operative CBCT scans [5], whereas others used the pink aesthetic score [4, 16], and finally, some studies did not specify how the outcome was measured at all [1, 10,11,12,13,14, 17, 19, 22, 25, 26] and merely stated a good outcome was achieved.

Complications

Six out of 18 studies reported on possible complications with the socket-shield technique [12, 13, 20, 23].

The exposure (internal and/or external) of the socket shield as reported by Gluckman et al. [12] was the most commonly reported complication pertinent to the socket-shield technique with a total of 17 exposed socket shields reported. Gluckman et al. [12] reported 12 internal and 4 external shield exposures. Two of the external exposures required a connective tissue graft to achieve closure, and three infected socket shields required removal of the socket shield altogether; however, the implants were able to be retained.

The remaining complications reported were resorption of the socket shield (2), peri-implantitis (2), non-integration of implants, or failed implant integration (7).

Discussion

The majority of publications identified relating to the socket-shield technique are clinical case reports and are unfortunately of little scientific value.

Therefore, the “Discussion” section will mainly focus on four clinical trials identified in the literature [4, 8, 12, 24] as well as publications by Hurzeler et al. [1] due to its impact as proof of concept, and Mitsias et al. [18] and Schwimer et al. [2] as they represent the only available human histologies to date.

In general, cohort size in the clinical trials varied significantly. Gluckman et al. [12] reported a large cohort of 128 implants followed up over a significant period of up to 9 years which has weighted influence on the data presented in this literature review. The remaining trials had very small cohorts and short observation times.

Hurzeler et al. [1] first reported the socket-shield technique as a proof of concept in an animal model. Whilst they were able to demonstrate the formation of a bony layer between the socket shield and the implant surface through histological evaluation, the animal model poses limitations when the technique is translated to humans.

Mitsias et al. [18] and Schwimer et al. [2] demonstrated similar outcomes.

The article by Bramanti et al. [4], whilst of small cohort size and short observation period, constituted the only randomised clinical trial to date in literature. However the surgical protocol in this study did vary from the technique described by Hurzeler et al. [1] in so far as the implant preparation was performed with the tooth root in place, which was split just prior to implant placement. Bramanti et al. [4] furthermore were the only study group concluding that bone graft in combination with the socket-shield technique is mandatory. This is in direct contrast to Hurzeler et al. [1] who concluded that an advantage of the socket-shield technique would be the fact that bone grafting with its cost and added complexity is not required.

With regard to clinical evaluation of the socket-shield technique, only Baumer et al. [8] reported on volumetric changes affecting the buccal tissues complex. Siormpas et al. [23] evaluated radiographic changes affecting the remaining root fragment, whilst Gluckman et al. [12] focused exclusively on clinical complications.

Bramanti et al. [4] did report the pink aesthetic score.

Therefore, inconsistent use of reporting measures across the studies severely limited comparison of results.

Surprisingly, as the vast majority of socket-shield implants reported placed were in the cosmetic zone, use of a relevant and consistent method of evaluation such as a pink aesthetic score, or more preferably determination of volumetric changes, was found to be rare.

The study by Baumer et al. [8], which was the only study to evaluate volumetric changes, reported only subtle facial tissue changes when compared to conventional immediate implant placement and restoration techniques.

Whilst their results were encouraging and showed similar, if not superior outcomes to conventional treatment protocols, the small cohort size limits what conclusions can be drawn.

Siormpas et al. [23] on the other hand used radiographs exclusively to assess bone changes following implant placement. Consequently, assessment was limited to a 2-dimensional analysis of space changes. Given that the rationale behind the socket-shield technique is to preserve buccal volume after implant placement, and that this is not discernible from conventional two-dimensional radiographs, this manuscript provides very limited evidence supporting the technique.

Gluckman et al. [12] reported low complication rates; the most common adverse outcome reported was the exposure of the root fragment either internally ( towards the implant restoration) or externally (exposure towards the buccal soft tissue). The authors reported that neither of these complications were difficult to manage or caused an adverse aesthetic outcome.

Conclusion

Whilst the socket-shield technique potentially offers promising outcomes, reducing the need for invasive bone grafts around implants in the aesthetic zone, clinical data to support this is very limited. The limited data available is compromised by a lack of well-designed prospective randomised controlled studies. The existing case reports are of very limited scientific value. Retrospective studies exist in limited numbers but are of inconsistent design. At this stage, it is unclear whether the socket-shield technique will provide a stable long-time outcome.

Hence, caution is advised at this stage when using the socket-shield technique in routine dental practice. Clinicians are advised to exercise best clinical judgement when considering to use the socket-shield technique for treatment.

Further clinical studies, preferably prospective randomised controlled clinical trials involving power analysis to determine an adequate cohort size to inform statistical interpretation which would allow conclusions to be drawn, are desirable.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset(s) supporting the conclusions of this article is available in PubMed.

References

Hurzeler MB, et al. The socket-shield technique: a proof-of-principle report. J Clin Periodontol. 2010;37(9):855–62.

Schwimer C, et al. Human histologic evidence of new bone formation and osseointegration between root dentin (unplanned socket-shield) and dental implant: Case Report. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2018;33(1):e19–23.

Mourya A, et al. Socket-shield technique for implant placement to stabilize the facial gingival and osseous architecture: a systematic review. J Investig Clin Dent. 2019;10(4):e12449.

Bramanti E, et al. Postextraction dental implant in the aesthetic zone, socket shield technique versus conventional protocol. J Craniofac Surg. 2018;29(4):1037–41.

Dary HA, Hadidi AA. The socket shield technique using bone trephine: a case report. Int J Dent Oral Sci. 2015:1–5.

Arabbi KC, et al. Socket shield: a case report. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2019;11(Suppl 1):S72–5.

Baumer D, et al. The socket-shield technique: first histological, clinical, and volumetrical observations after separation of the buccal tooth segment - a pilot study. Clin Implant Dent Relat Res. 2015;17(1):71–82.

Baumer D, et al. Socket shield technique for immediate implant placement - clinical, radiographic and volumetric data after 5 years. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2017;28(11):1450–8.

Cherel F, Etienne D. Papilla preservation between two implants: a modified socket-shield technique to maintain the scalloped anatomy? A case report. Quintessence Int. 2014;45(1):23–30.

Dayakar M, et al. The socket-shield technique and immediate implant placement. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2018;(5):22.

Glocker M, Attin T, Schmidlin P. Ridge preservation with modified “Socket-Shield” technique: a methodological case series. Dentistry J. 2014;2(1):11–21.

Gluckman H, Salama M, Du Toit J. A retrospective evaluation of 128 socket-shield cases in the esthetic zone and posterior sites: partial extraction therapy with up to 4 years follow-up. Clin Implant Dent Relat Res. 2018;20(2):122–9.

Gluckman H, Du Toit J, Salama M. The pontic-shield: partial extraction therapy for ridge preservation and pontic site development. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 2016;36(3):417–23.

Guo T, et al. Tissue preservation through socket-shield technique and platelet-rich fibrin in immediate implant placement. Medicine. 2018;97(50).

Han CH, Park KB, Mangano FG. The modified socket shield technique. J Craniofac Surg. 2018;29(8):2247–54.

Huang H, et al. Immediate implant combined with modified socket-shield technique: a case letter. J Oral Implantol. 2017;43(2):139–43.

Kan JYK, Rungcharassaeng K. Proximal socket shield for interimplant papilla preservation in the esthetic zone. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 2013;33(1):e24–31.

Mitsias ME, et al. The root membrane technique: human histologic evidence after five years of function. Biomed Res Int. 2017;2017:7269467.

Mitsias ME, et al. A step-by-step description of PDL-mediated ridge preservation for immediate implant rehabilitation in the esthetic region. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 2015;35(6):835–41.

Szmukler-Moncler S, et al. Unconventional implant placement part III: implant placement encroaching upon residual roots - a report of six cases. Clin Implant Dent Relat Res. 2015;17(Suppl 2):e396–405.

Nevins ML, Langer L, Schupbach P. Late dental implant failures associated with retained root fragments: case reports with histologic and SEM analysis. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 2018;38(1):9–15.

Saeidi Pour R, et al. Clinical benefits of the immediate implant socket shield technique. J Esthet Restor Dent. 2017;29(2):93–101.

Siormpas KD, et al. Immediate implant placement in the esthetic zone utilizing the “root-membrane” technique: clinical results up to 5 years postloading. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2014;29(6):1397–405.

Siormpas KD, et al. The root membrane technique. Implant Dent. 2018;27(5):564–74.

Wadhwani P, et al. Socket shield technique: a new concept of ridge preservation. Asian J Oral Health Allied Sci. 2015;5(2):55–8.

Gluckman H, Du Toit J, and S. M. Guided bone regeneration of a fenestration complication at implant placement simultaneous to the socket-shield technique. Int J. 5(4): p. 58-64.

Gluckman H, Salama M, Du Toit J. Partial extraction therapies (PET) part 2: procedures and technical aspects. Int J Periodont Restorative Dent. 2017;37(3):377–85.

Acknowledgements

All illustrations courtesy of Prof M. Hurzeler, Munich, Germany.

Funding

No external funding for this article was received.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Main body and literature research was done by Dr Blaschke; article review and secondary input were done by Dr Schwass. The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable

Consent for publication

All figures were supplied by Prof Hurzeler and consented for publication

Competing interests

Dr. Christian Blachke and Dr. Donald Schwass declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Blaschke, C., Schwass, D.R. The socket-shield technique: a critical literature review. Int J Implant Dent 6, 52 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40729-020-00246-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40729-020-00246-2