Abstract

Background

Laser based flow visualization techniques are indispensable tools for flow visualization in fluid dynamics and combustion diagnostics. Among these, PLIF is very popular because of its capability to give quantitative information about the flow. This paper reports the acetone tracer-based PLIF imaging of supersonic jet with air and nitrogen as bath gases.

Methods

The tracer was seeded in the flow by purging bath gas through the liquid acetone at ambient temperature. Planar laser sheet from frequency quadrupled, Q-switched, Nd:YAG laser (266 nm) was used as an excitation source. Emitted PLIF images of a jet flow field were recorded on ICCD camera.

Results

In this study, the dependence of PLIF images intensity on oxygen by comparing nitrogen jet with air in supersonic regime was presented. A lower temperature at the exit of the supersonic jet condenses the tracer which in turn forms droplets.

Conclusions

There was a significant decrease in the PLIF image intensity in the case of air. This may be attributed to the oxygen present in the air. It is shown that image adding and Gaussian image processing of PLIF images for steady-state jet improve the quality of images.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Better understanding of supersonic jet is necessary owing to its enormous applications in aerospace engineering, such as thrust generation for rockets, gas turbines, gas mixing and jet noise reduction. Extensive investigations have been carried out by several researchers to understand such phenomena (Mitchell et al. 2007; Leyko et al. 2011; Morris et al. 2013). Supersonic jets are routinely created in the laboratory by allowing high pressure gas to escape through a convergent-divergent (C-D) nozzle into a low pressure gas region. For studying such supersonic jets, optical flow visualization techniques are frequently used. It is noted that optical techniques such as Schlieren, shadowgraphy, planar laser-induced fluorescence (PLIF), and Planar Mie scattering are often employed in supersonic jet flow visualization studies (Raffel et al. 2000; Leonov et al. 2010; Herring and Hillard 2000). Among these methods, schlieren photography is very popular and is frequently used due to its capability of directly recording gas density variations. Thus, laser based flow visualization techniques are indispensable tools for flow visualization in fluid dynamics and combustion diagnostics. Among these, PLIF is very popular because of its capability to give quantitative information about the flow. Imaging at a nanosecond time scale using laser pulses will lead to better probing of short timescale phenomenon (Crimaldi 2008; Schulz and Sick 2005). In this technique, a suitable molecular tracer is added into the flow for recording flow images. The tracer selection is more crucially dependent upon the quantity to be measured and the relevant photophysical characteristics of the tracer. Most of the previous work on PLIF imaging of supersonic jet uses diatomic molecules as tracers, for example NO and OH (Arnette et al. 1993; Rossmann et al. 2001; Hsu et al. 2009; Lachney and Clemens 1998; Palmer and Hanson 1995). One of the major difficulties in using diatomic molecules is their narrow absorption wavelength range. Thus, lasers of specific wavelengths have to be used as an excitation source. Higher gas temperature is necessary for the formation of most of the diatomic molecules or radicals in the flow, which is very difficult in case of low temperature supersonic flow facilities.

Major problems of supersonic flow visualization using polyatomic molecular tracers are low vapor pressure, condensation of the tracers, due to low temperatures prevailing in the flow region, and collisional quenching of the fluorescence at high pressures. Ketones are the most frequently used organic carbonyls as tracers in gas flow visualization experiments. Among these, acetone has been extensively studied and used for jet flow visualization at subsonic and supersonic velocities (Lozano et al. 1992; Yuen et al. 1997; Thurber and Hanson 1999; Thurber and Hanson 2001; Löffler et al. 2010; Handa et al. 2011; Shelar et al. 2014). Löffler et al. (2010) reported the calibration data of acetone laser-induced fluorescence (LIF) in an internal combustion engine for quantitative measurement of temperature and pressure. Handa et al. (2011) showed that acetone PLIF can be used for supersonic jet flow visualization, even though it suffers from low temperature condensation. Oxygen is invariably present in many gas flow experiments and leads to quenching of fluorescence emission (Shelar et al. 2014). Thus, a quantitative understanding of the effect of oxygen on LIF intensity is very essential. Fluorescence quenching in organic molecules by oxygen and other quenchers is well known in liquid and gas phase (Shelar et al. 2014; Thipperudrappa et al. 2004; Arik et al. 2005).

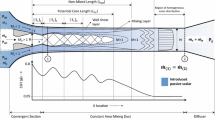

When the free jet from a C-D nozzle expands into the ambient atmosphere, an interaction between expansion and compression waves produce a typical structure termed oblique shocks and one or more normal shocks, known as Mach disks. When an external pressure or back pressure is higher than the exit pressure at the nozzle, flow compression is in backward direction and separate from the walls of the nozzle. This is called an overexpanded jet; otherwise, it is called underexpanded. A supersonic overexpanded jet structure is well known in the previous literature and is visualized by different techniques. Figure 1 shows a typical overexpanded steady-state shock cell structure in a supersonic jet (Arnette et al. 1993; Norman et al. 1982; Hadjadj and Onofri 2009)

.

In the present study, acetone is used as the tracer and a high-speed intensified, gated CCD camera is used for supersonic jet flow visualization by the PLIF technique at Mach number 2.5. The PLIF image of the supersonic jet was compared with the schlieren image for the same tank pressure conditions. Image adding and Gaussian filters are used to improve the quality of the recorded PLIF images. In order to study the effect of oxygen in real-time flow, air was used as the bath gas and the results were compared with nitrogen for four different tank pressures. An improved methodology has been proposed for PLIF imaging of supersonic flow using an acetone tracer.

Methods

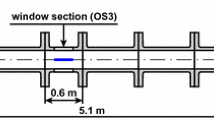

Figure 2 shows an experimental setup used for PLIF imaging of the supersonic jet employed for the present study. The supersonic jet of nitrogen or air was created in our laboratory using an axisymmetric C-D nozzle with a throat diameter of 2 mm and an exit diameter of 5 mm. The bath gases, nitrogen or air contained in high pressure cylinders, were purged through the liquid acetone, taken in a bottle, and then passed through the C-D nozzle into the ambient atmosphere.

In the setup, a laser beam of 266 nm wavelength from an Nd:YAG laser (Model LAB190, Spectra Physics Inc, Santa Clara, CA, USA.) was transformed into a planar laser sheet using a cylindrical lens. The laser beam was shaped into a planar sheet with a width of 5 cm and thickness of 15 μm at focus using the combination of cylindrical plano-convex and spherical plano-convex lenses of suitable focal lengths. For imaging purposes, a high-speed gated ICCD camera (Model-4 Quik E/digital HR) from Stanford Computer Optics Inc. (Berkeley, CA, USA) with a minimum gate time of 1.2 ns was employed. The camera was connected to the computer and Nd:YAG laser for external trigger. After each laser pulse, the camera shutter opening delay was set to 50 ns and the optimized exposure time was fixed to 25 ns throughout the experiment. To filter out other stray light, an acetone LIF filter (LaVision GmbH, Göttingen, Germany) was placed in front of the camera. The linear fluorescence regime was ensured by keeping incident laser energy at 20 mJ/pulse, which is well below the saturation intensity for acetone.

The schlieren imaging technique has been frequently used in flow visualization of various types for flows. Hence, for calibration and comparison purposes, we have used a conventional schlieren setup with concave mirrors as shown in Figure 3 (Liepmann and Roshko 1957). Schlieren imaging is based on the principle that light rays deflected due to the variation in refractive index are blocked from reaching the camera or viewing screen. In these experiments, we have used a xenon lamp as the light source and concave mirrors, with a diameter of 100 mm and a focal length of 1,000 mm, as the imaging elements. A sharp stainless steel blade was used as the knife edge. The details of the experimental technique are given elsewhere (Satheesh et al. 2007).

Results and discussion

The supersonic underexpanded jet structure is well known in the previous literature, whereas the overexpanded jet structure needs to be understood more clearly (Arnette et al. 1993). Figure 1 shows the typical overexpanded shock cell structure in a supersonic jet. We have employed an acetone tracer-based PLIF technique to visualize supersonic nitrogen and air jet. The main challenge in implementing acetone PLIF in supersonic jets are condensation of the tracer at the exit of the nozzle and low signal to noise ratio at higher velocities. It is observed that the PLIF intensity in a single shot image was very poor. As seen in Figure 4a, we cannot observe any flow structure in the image as obtained from the camera. Thus, images were obtained at 10 Hz frequency and stored. Each final processed image was obtained by binning or adding 500 such images as shown in the Figure 4b. Figure 5 shows the overexpanded PLIF image of the nitrogen jet of Mach 2.5 for four different tank pressures.

Figure 6 shows the effect of the number of images added on the gray scale intensity of the image for 18-bar tank pressure. We can clearly see that for steady-state jets, image addition gives better results. Each steady-state PLIF image was obtained by adding 500 images. Oblique shock waves and the Mach disk are clearly observed. The PLIF images usually have defects such as bad pixilation. Hence, image processing is essential to correct such defects and improve the quality of the image. At the beginning, the defected pixel values were identified based on the abrupt variation in the intensity value and corrected by averaging. This was followed by smoothing the image by convolving with a Gaussian filter. The Gaussian filter in vertical (m) and horizontal (n) direction makes use of the two-dimensional Gaussian functions given by the following equation

The size of the discrete matrix (m, n) and the value of the standard deviation σ of the Gaussian function can be changed depending on the quality of the image. In the present work, the optimized matrix size and σ for the processed images are 6 × 6 and 1, respectively. Gaussian smoothing is primarily used as edge detection, and hence, there is noise reduction in the image (Acharya and Ray 2005; Solomon and Breckon 2011).

For the same conditions, acetone PLIF image for 18 bar tank pressure is compared with the schlieren image. Figure 7 shows the comparison between schlieren and acetone PLIF images. The brighter regions in the PLIF image correspond to the darker regions in the schlieren and vice versa. The position of the shock cell for both images is in good agreement with each other. We notice that the brighter regions in the PLIF image correspond to a large number density of tracers leading to higher intensity. Thus, for steady-state jets, despite the problem of condensation, it is possible to get more information on the shock waves and shock cell structure using acetone PLIF. To study the effect of oxygen on intensity of a jet image, air was used as a bath gas instead of nitrogen. Figure 8 shows the comparison between processed acetone PLIF images of air and nitrogen at four different tank pressures keeping other conditions same. Image intensities at the two different cross sections (see Figure 9), one at the middle of the shock cell (A) and the other at the center of the Mach disk (B) is presented in Figure 10a,b. We clearly observe that there is a drop in the intensity in the case of air compared with nitrogen. The middle of the shock cell jet expansion was nearly 1.5 times greater than the nozzle exit diameter (D) and same as the nozzle diameter in the Mach disk. Also we see that the signal noise level in the image away from shock boundaries is same for both air and nitrogen. Shock waves cannot be observed unambiguously in the case of air. This decrease in the intensity is due to the fluorescence quenching effect by molecular oxygen. Oxygen is usually present in its ground triplet state. The energy transfer through non-radiative decay may lead to the reduction in intensity of the images in the case of air. In the previous work, we have investigated the effect of oxygen in static cell and found that fluorescence quenching is present in ketones and is collisional in nature (Shelar et al. 2014). Further, Figure 11 shows the effect of air pressure on the average gray scale intensity of the image. There is a linear drop in the intensity, which is due to a collisional transfer from acetone to triplet oxygen. As tank pressure increases, collisions between bath gas and tracer molecules also increase. This collisional energy transfer diminishes the LIF intensity with the increase in pressure. Thus, we proposed a simple method to record and improve the acetone PLIF image of a supersonic jet for quantitative flow visualization.

Gray scale intensity in nitrogen and the air jet. At (a) the middle of the shock cell and at (b) the center of the Mach disks indicated in Figure 9.

Conclusions

Supersonic nitrogen and air jet are visualized by employing a PLIF technique using acetone as the tracer. In spite of the major problem of condensation of acetone, it is demonstrated that acetone can be used for steady-state supersonic jet flow visualization and mixing studies. Image processing and image addition enhances the quality of the steady-state PLIF image. Effect of oxygen is clearly observed in air flow at supersonic speeds. It is found that there is a decrease in the image intensity with increase in tank pressure for air. This is attributed to collisional transfer from acetone to triplet oxygen. The proposed method can easily be applied to quantitative flow visualization studies of supersonic flows.

References

Acharya, T, & Ray, AK. (2005). Image Processing Principles and Applications (pp. 105–155). A John Wiley & Sons Inc. Publication Hoboken New Jersey.

Arik, M, Celebi, N, & Onganer, YJ. (2005). Fluorescence quenching of fluorescein with molecular oxygen in solution. Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology A: Chemistry, 170, 105–111.

Arnette, SA, Samimy, M, & Elliott, GS. (1993). On stream wise vortices in high Reynolds number supersonic axisymmetric jets. Physics of Fluids A: Fluid Dynamics, 5, 187–202.

Crimaldi, JP. (2008). Planar laser induced fluorescence in aqueous flows. Experiments in Fluids, 44, 851–863.

Hadjadj, A, & Onofri, M. (2009). Nozzle flow separation. Shock Waves, 19, 163–169.

Handa, T, Masuda, M, Kashitani, M, & Yamaguchi, Y. (2011). Measurement of number densities in supersonic flows using a method based on laser-induced acetone fluorescence. Experiments in Fluids, 50, 1685–1694.

Herring, GC, & Hillard, ME. (2000). Flow Visualization by Elastic Light Scattering in the Boundary Layer of a Supersonic Flow. NASA/TM-2000-210121.

Hsu, A, Srinivasan, R, Bowersox, RDW, & North, SW. (2009). Application of Molecular Tagging Towards Simultaneous Vibrational Temperature and Velocity Mapping in an Underexpanded Jet Flowfield. Orlando, Florida: 47th AIAA Aerospace Sciences.

Lachney, ER, & Clemens, NT. (1998). PLIF imaging of mean temperature and pressure in a supersonic bluff wake. Experiments in Fluids, 24, 354–363.

Leonov, SB, Savelkin, KV, Firsov, AA, & Yarantsev, DA. (2010). Fuel ignition and flame front stabilization in supersonic flow using electric discharge. High Temperature, 48(6), 896–902.

Leyko, M, Moreau, S, Nicoud, F, & Poinsot, T. (2011). Numerical and analytical modelling of entropy noise in a supersonic nozzle with a shock. Journal of Sound and Vibration, 330, 3944–3958.

Liepmann, HW, & Roshko, A. (1957). Elements of Gas Dynamics. New york: John wiley and sons inc.

Löffler, M, Beyrau, F, & Leipertz, A. (2010). Acetone laser-induced fluorescence behavior for the simultaneous quantification of temperature and residual gas distribution in fired spark-ignition engines. Applied Optics, 49(1), 37–49.

Lozano, A, Yip, B, & Hanson, RK. (1992). Acetone: a tracer for concentration measurements in gaseous flows by planar laser-induced fluorescence. Experiments in Fluids, 13, 369–376.

Mitchell, D, Honnery, D, & Soria, J. (2007). Study of Underexpanded Supersonic Jets with Optical Techniques. Crown Plaza, Gold Coast, Australia: 16th Australasian Fluid Mechanics Conference.

Morris, PJ, McLaughlin, DK, & Kuo, CW. (2013). Noise reduction in supersonic jets by nozzle fluidic inserts. Journal of Sound and Vibration, 332, 3992–4003.

Norman, ML, Smarr, L, Winkler, KHA, & Smith, MD. (1982). Structure and dynamics of supersonic jets. Astronomy and Astrophysics, 113, 285–302.

Palmer, JL, & Hanson, RK. (1995). Shock tunnel flow visualization using planar laser induced fluorescence imaging of NO and OH. Shock Waves, 4, 313–323.

Raffel, M, Richard, H, & Meier, GEA. (2000). On the applicability of background oriented optical tomography for large scale aerodynamic investigations. Experiments in Fluids, 28, 477–481.

Rossmann, T, Mungal, MG, & Hanson, RK. (2001). Nitric-oxide planar laser-induced fluorescence applied to low-pressure hypersonic flow fields for the imaging of mixture fraction. Applied Optics, 42(33), 6682–6695.

Satheesh, K, Jagdeesh, G, & Reddy, KPJ. (2007). High speed schlieren facility for visualization of flow fields in hypersonic shock tunnels. Current Science, 92(1), 56–60.

Schulz, C, & Sick, V. (2005). Tracer-LIF diagnostics: quantitative measurement of fuel concentration, temperature and fuel/air ratio in practical combustion systems. Progress in Energy and Combustion Science, 31, 75–121.

Shelar, VM, Hegde, GM, Umesh, G, Jagadeesh, G, & Reddy, KPJ. (2014). Gas phase oxygen quenching studies of ketone tracers for laser induced fluorescence applications in nitrogen bath gas. Spect Lett, 47(1), 12–18.

Solomon, C, & Breckon, T. (2011). Fundamentals of Image Processing a Practical Approach With Examples in Matlab (pp. 95–96). UK: A John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

Thipperudrappa, J, Biradar, DS, Lagare, MT, Hanagodimath, SM, Inamdara, SR, & Kadadevaramath, JS. (2004). Fluorescence quenching of Bis-msb by carbon tetrachloride in different solvents. Journal of Photoscience, 11(1), 11–17.

Thurber, MC, & Hanson, RK. (1999). Pressure and composition dependences of acetone laser-induced fluorescence with excitation at 248, 266, and 308 nm. Applied Physics B, 69, 229–240.

Thurber, MC, & Hanson, RK. (2001). Simultaneous imaging of temperature and mole fraction using acetone planar laser-induced fluorescence. Experiments in Fluids, 30, 93–101.

Yuen, LS, Peters, JE, & Lucht, RP. (1997). Pressure dependence of laser-induced fluorescence from acetone. Application Opt, 36(15), 3271–3277.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Prof. R. V. Ravikrishna, Mr. Saurabha Markandeya, and Mr. S. Krishna of the Department of Mechanical Engineering, Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore. Authors also wish to acknowledge DRDO for the financial support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

The main author VMS carried out the research and designed the experiment. SRMV was responsible for setting up supersonic jet and provided technical details for the same. GMH and GU were responsible for technical supervision. GMH checked the paper and provided suggestions to improve the paper. GJ and KPJ provided suggestions to improve the experimental quality of the work. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits use, duplication, adaptation, distribution, and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Shelar, V.M., MV, S.R., Hegde, G. et al. Acetone planar laser-induced fluorescence for supersonic flow visualization in air and nitrogen jet. Int J Mech Mater Eng 9, 28 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40712-014-0028-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40712-014-0028-1