Abstract

Purpose of the review

Among hospitalized patients, acute kidney injury is common and associated with significant morbidity and risk for mortality. The use of electronic health records (EHR) for prediction and detection of this important clinical syndrome has grown in the past decade. The steering committee of the 15th Acute Dialysis Quality Initiative (ADQI) conference dedicated a workgroup with the task of identifying elements that may impact the course of events following Acute Kidney Injury (AKI) e-alert.

Sources of information

Following an extensive, non-systematic literature search, we used a modified Delphi process to reach consensus regarding several aspects of the utilization of AKI e-alerts.

Findings

Topics discussed in this workgroup included progress in evidence base practices, the characteristics of an optimal e-alert, the measures of efficacy and effectiveness, and finally what responses would be considered best practices following AKI e-alerts. Authors concluded that the current evidence for e-alert system efficacy, although growing, remains insufficient. Technology and human-related factors were found to be crucial elements of any future investigation or implementation of such tools. The group also concluded that implementation of such systems should not be done without a vigorous plan to evaluate the efficacy and effectiveness of e-alerts. Efficacy and effectiveness of e-alerts should be measured by context-specific process and patient outcomes. Finally, the group made several suggestions regarding the clinical decision support that should be considered following successful e-alert implementation.

Limitations

This paper reflects the findings of a non-systematic review and expert opinion.

Implications

We recommend implementation of the findings of this workgroup report for use of AKI e-alerts.

ABRÉGÉ

Contexte et objectifs de la revue

L’insuffisance rénale aigüe (IRA) est un problème de santé fréquent chez les patients hospitalisés, et elle présente un risque élevé de morbidité et de mortalité pour les personnes affectées. L’utilisation des dossiers médicaux électroniques (DMÉ) pour la prédiction et le dépistage de ce syndrome clinique est en croissance depuis une dizaine d’années. Le comité directeur de la 15e réunion annuelle de la Acute DIalysis Quality Initiative (ADQI) a désigné un groupe de travail à qui il a donné le mandat d’identifier les éléments susceptibles d’avoir une incidence sur le cours des événements à la suite d’une alerte électronique indiquant un changement dans le taux de créatinine sérique d’un patient (alerte électronique d’IRA).

Sources et méthodologie

À la suite d’une revue exhaustive, mais non systématique de la littérature, nous avons utilisé une version modifiée de la méthode Delphi afin de parvenir à un consensus sur plusieurs facteurs liés à l’utilisation des alertes électroniques IRA.

Résultats/constatations

Parmi les thèmes discutés par ce groupe de travail figuraient les progrès observés au niveau de la pratique factuelle, l’identification des caractéristiques d’une alerte électronique optimale, la façon de mesurer l’efficacité des alertes et enfin, les interventions qualifiées de pratiques exemplaires à appliquer à la suite d’une alerte électronique d’IRA. Les auteurs ont conclu que les connaissances actuelles sur l’efficacité des systèmes d’alertes électroniques, bien qu’en progression, demeurent insuffisantes. Ils ont de plus identifié les facteurs humains et technologiques comme étant des éléments clés à considérer lors d’investigations futures portant sur de tels systèmes ou lors de leur mise en œuvre dans le futur. Le groupe de travail a également conclu que la mise en place de tels systèmes d’alertes ne devrait toutefois pas se faire sans un programme rigoureux d’analyse de l’efficacité et de l’efficience des alertes émises, et que ces mesures devraient se faire dans un cadre précis et en tenant compte des résultats observés chez les patients. Enfin, les auteurs ont fait plusieurs suggestions de mécanismes d’aide à la prise de décisions cliniques à prendre en considération à la suite de la mise en œuvre réussie d’un système d’alertes électroniques.

Limites

Cet article fait état des conclusions obtenues dans le cadre d’une revue non systématique de la littérature et à partir des opinions d’un groupe d’experts.

Conclusion

Nous recommandons la mise en application des conclusions émises dans le rapport présenté par le groupe de travail sur l’utilisation des alertes électroniques IRA.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Acute kidney injury (AKI) is defined by the Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) definition, which is a modification of the RIFLE (risk, injury, failure, loss, and end-stage kidney disease) and acute kidney injury network (AKIN) consensus definitions for AKI [1–3]. This definition involves the evaluation of an absolute or relative increase in serum creatinine (hereafter called 'creatinine') or oliguria for six or more hours. At first sight, these criteria seem simple and straightforward. However, appropriate detection of AKI requires knowledge of a baseline creatinine or reference creatinine, calculation of urine output / body weight per hour, and calculation of time periods during which the change in creatinine or urine output occurs [4]. This makes an evaluation of the occurrence of AKI and staging of severity complex and labor-intensive.

Information technology is increasingly used in the healthcare setting for the integration of all available data as an aid to clinical decision-making. The individual elements that are necessary for the definition and staging of AKI are typically available in the integrated electronic health record (EHR) or intensive care clinical information system. Therefore, an electronic sniffer or electronic-alert (e-alert) can potentially detect AKI each time creatinine or urine output is recorded.

The steering committee of the 15th Acute Dialysis Quality Initiative (ADQI) conference dedicated a workgroup with the task of considering elements that may impact the course of events following AKI e-alert. More specifically, they were asked to address a set of 4 questions:

-

1.

What is the evidence base regarding AKI e-alerting?

-

2.

What are the characteristics of an optimal e-alert?

-

3.

How should we assess the efficacy and effectiveness of e-alerts?

-

4.

What responses can be considered best practices?

These questions served as a basis for accompanying consensus statements. Our group was also asked to provide a critical evaluation of the relevant literature to summarize the methodology, scope, implementation and evaluative strategies for EHR-based clinical decision support.

Review

This consensus meeting following the established ADQI process, as previously described [5]. The broad objective of ADQI is to provide expert-based statements and interpretation of current knowledge for use by clinicians according to professional judgment and identify evidence care gaps to establish research priorities.

The 15th ADQI Consensus Conference Chairs convened a diverse panel representing relevant disciplines (i.e., nephrology, critical care, pediatrics, pharmacy, epidemiology, health services research, biostatistics, bioinformatics and data analytics) from five countries from North America and Europe around the theme of “Acute Kidney Injury in the Era of Big Data” for a 2-day consensus conference in Banff, Canada on September 6-8, 2015.

Before the conference we searched the literature for evidence on methodologies for design, integration and implementation of novel applications into the electronic health records that enable "alerting" of changes in clinical status and provide a modality of clinical decision support. A formal systematic review was not conducted.

A pre-conference series of call conferences and emails involving the work group members was used to identify the current state of knowledge to enable the formulation of key questions from which discussion and consensus would be developed.

During the conference, our work group developed consensus positions, and plenary sessions involving all ADQI contributors were used to present, debate, and refine these positions.

Following the conference, this summary report was generated, revised, and approved by all members of the workgroup.

What is the evidence base regarding AKI e-alerting?

Consensus statement 1

Current evidence is limited by the number of studies, their heterogeneity (design of the sniffer, location, clinical action, outcomes measured, etc.), and contradictory results.

An overview of studies that report on the use of e-alerts for AKI is presented in Table 1. We identified two groups of studies on e-alerts and AKI. The first category reported the utilization of an e-alert without measurement of their impact on the process of care and patient or kidney outcomes [6–12]. In the second group, processes of care or outcomes were measured, but e-alerting did not improve outcomes [13–15]. Finally, in the third set of studies, recorded clinical outcomes or quality of care indicated improvement [16–26]. Despite a relatively large number of patients studied, the actual number of centers where these e-alerts were evaluated was limited. In addition, we found that there was considerable heterogeneity among studies, which makes systematic analysis difficult.

What is an optimal e-alert?

Consensus statement 2

There are several technological and human factors that need to be considered during the implementation and evaluation of an AKI e-alert system. These elements include but are not limited to the clinical context, location, provider, e-alert accuracy, the hierarchy of disruptiveness (i.e., the extent to which the alert disrupts the current workflow), delivery methods, alarm philosophy, and outcome expectations in clinical and administrative settings.

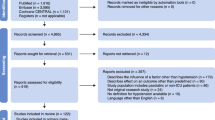

The turn of events that leads to the process of care modification or clinical outcomes following the firing of an e-alert is illustrated in Fig. 1. Although the role of the EHR in the care and management of patients with AKI is potentially important, literature regarding the characteristics of an effective AKI e-alert is scarce. Several components have been described to change the effectiveness and acceptance of e-alert systems for other clinical and administrative purposes. The depth of knowledge that is generated by the EHR could be divided to basic and advanced. Basic e-alerts disregard the clinical context or have low precision; therefore, it is not surprising that e-alerts with basic capabilities are not widely accepted in the clinical practice [27–36]. In comparison, advanced e-alerts assist clinicians by including information regarding the clinical context and possess significantly higher sensitivity and specificity. Advanced e-alerts can potentially play a significant role in easing the heavy workload of clinicians by enhancing safety measures and efficacy without creating a distraction.

The process of electronic-alert from exposure to outcome. An e-alert should impact on logistical or clinical outcomes. In this process exposure to the e-alert components (technology and human factors, delivery methods) potentially results in a change of behavior of the provider. Crucial to this process is the acceptance of the alert by the provider. Reproduced with permission from ADQI (www.adqi.org)

Despite the advantages of utilizing the e-alert system abilities, the method of delivery may impact their acceptance into the clinical practice. Phansalkar et al. described these features as human factors and divided them into several distinct elements [37, 38]. These components include: alarm philosophy (defining the unsafe situations that require alarming), placement (within or outside of visual horizon), visualization (target size, luminance, background contrast), prioritization (using appropriate wording for different urgency levels), textual information (to include priority, information regarding the nature of the alert, recommendation and a statement to indicate the consequence of ignoring the alert), and habituation (decreased response to alarms over time). Implementation of irrelevant alarms also has an adverse impact on the acceptance of e-alerts by clinicians. These type of alarms could be defined as warnings that do not require a response by care providers. They are irrelevant to the patient quality of care and safety, or they generate significant false positive warnings. Further, Seidling et al. included these factors in a scale and based on their performance and characteristics divided them to poor, moderate and excellent e-alerts [39]. In order to set up a successful e-alert system, one needs to consider other variables including the patient setting (intensive care units (ICU) where patients already undergo close monitoring, versus hospital ward or outpatient clinic in which patient data are scarce), the hierarchy of disruption (the spectrum of disruption ranging from no-alert to a hard stop without rights to override), frequency of alerts (alert submission till resolution of the issue versus alert submission only once), timing (real time versus set time for submission all in clusters), provider acknowledgement requirements (no need for response versus punitive measures if response is not provided), target of e-alert (physician, midlevel provider, trainees, nurses, or patients), and finally content of alarm (AKI diagnosis or risk prediction, and clinical decision support). Furthermore, cultural differences based on the type (community versus teaching) and size (small versus large hospitals) of the institution, geographical locations (continents, countries, counties), services (medical versus surgical), providers (subspecialists, specialists, midlevel, trainee, allied health staff) could significantly impact the performance of e-alerts in improvement of patient care and safety. Finally, what is expected from the e-alert system may define its success or failure. For example, if the expectation is to improve mortality of hospitalized patients, the alerts need to be very precise, disruptive, be tagged with a very sophisticated clinical decision support system, and if any study aims to show its efficacy it needs to include a very large number of patients. In comparison, when e-alerts are used for administrative purposes the level of disruptiveness and their required precision could be completely different.

To provide an example of how differences in the aforementioned factors can affect the performance of AKI e-alerts in various platforms, we present two recent published studies that focused on the impact of AKI e-alerts on patient and processes of care outcomes. Colpaert et al. described a single-center European prospective interventional study in which she used AKI alert via Digital Enhanced Cordless Technology (DECT) telephone to the intensivists [22]. This alert included information regarding changes in creatinine and urine output, and the alert was generated whenever AKI progressed to the next stage of RIFLE criteria [2]. She compared the processes of care in the periods before, during, and following alert implementation and found a significant increase in the number and timeliness of early therapeutic interventions during the alert phase. In comparison, Wilson et al. recently published results of a randomized controlled trial to evaluate the impact of a single alert via pager on the outcomes of hospitalized patients in a single center in the United States [15]. Alerts were generated solely based on absolute or relative rise in the creatinine level in comparison with the lowest creatinine level measured within the past 48 h (for 26 mmol/L [0.3 mg/dL] criteria) or 7 days (for 50 % relative increase criteria). Authors included adult patients from the medical and surgical ICUs, and floors and providers who received alerts were interns, residents, or nurse practitioners. This study did not show any improvement in the clinical outcomes or processes of care among hospitalized patients. These contrasting results highlight the importance of the e-alert system design and human factors on the clinical performance of the system.

How do we measure alert efficacy?

Consensus statement 3

E-alert efficacy and effectiveness should be measured proactively and encompass quality assurance, provider-based responses, and clinical outcomes.

The use of e-alerts for a variety of conditions has expanded dramatically in the past several years but has also placed new burdens on providers [38, 40–43]. In the best case scenarios, alerts can prevent medical error or promote timely and appropriate treatment of a severe condition. In the worst case scenarios, they can impede workflow, distract providers, and lead (indirectly) to patient harm.

Therefore, e-alert systems should not be adopted without a rigorous assessment of their benefit and risk across several domains. These evaluations, where possible, should be performed in the context of a randomized, controlled trial. However, even in settings where the performance of a randomized trial is not feasible, attention to key metrics both before and after e-alert implementation will aid in the assessment of efficacy.

Prior to the wide rollout of e-alert systems for AKI, careful testing of the system should be performed. Pre-testing of the system should include a systematic effort to determine whether the e-alert is capturing all patients of interest (by whatever AKI definition is being used) and is not erroneously alerting for patients without AKI. This may be a particular issue for individuals receiving dialysis for end-stage kidney disease, in whom inter-dialytic creatinine fluctuation may trigger alerts. In addition, a recent study has shown that false-positive AKI rates may be particularly high among individuals with chronic kidney disease when electronic monitoring of creatinine levels is employed [44].

After the alert system is appropriately calibrated, developers must ensure that the proper alert target is identified and reached. Challenges here can include identifying who the appropriate care provider or providers are to receive an alert and the mechanism by which they can be contacted.

Developers of e-alerts should perform system-wide implementation only when the above measures have been satisfied. Once alerting is broadly executed, several other efficacy metrics become important.

Depending on the context of the e-alert, various provider behaviors should be evaluated. Broadly, we consider provider-initiated electronic documentation of AKI and orders for follow-up creatinine and urine output assessment to be important metrics of alert efficacy. Other provider behaviors (such as the ordering of certain diagnostic tests, studies, changing drug dosing, and avoidance of nephrotoxins) may be appropriate efficacy measures in certain clinical contexts.

Provider actions, such as ordering subsequent lab testing, should be examined independently of the successful completion of the order (the actual blood being drawn). This ensures robust assessment of efficacy as well as avoiding systematic "workarounds". For example, if a provider is aware that an order for another creatinine test is a quality measure, he or she may order the test with no intention of having the test performed (for example, by specifying the blood to be drawn at a time after the patient is to be discharged).

Critically, clinical outcomes should be assessed in all e-alert systems, as there is some evidence that e-alerts may increase resource utilization without tangible patient-level benefit [15]. In the case of AKI e-alerts, clinical outcomes can include the receipt of dialysis, death, ICU transfer, and change in creatinine concentration among others.

We also suggest that efforts be made to gauge provider acceptance of e-alert systems. These studies can be quantitative or qualitative, but they should be undertaken concurrently with e-alert development and with the understanding that e-alert systems that do not integrate well into a provider perception of care are unlikely to demonstrate sustained benefit.

What responses can be considered best practices?

Consensus statement 4

Following AKI alert (risk or diagnosis), the clinician should confirm and document the risk or diagnosis in the clinical notes and EHR. Follow-up measurement of urine output and creatinine should be ordered, and the use of additional diagnostics be considered. Appropriate care or recommendations according to the best evidence-based practices for prevention or treatment should be utilized, and the effectiveness of clinical decision support systems (CDS) should be evaluated.

Increased severity of AKI is associated with increasing risk of death and other serious complications [45]. Therefore, there is increasing focus on the importance of early recognition and management of AKI, with the goal of potentially providing a wide therapeutic window for prevention and treatment [1, 46]. The use of e-alerts to enhance the compliance with AKI-related clinical practice guidelines offer the potential for minimizing the impact of AKI [1, 22, 26, 27]. However, it is evident that physician notification by e-alert alone is not adequate to ensure an optimal response in patients with probable AKI [15]. Alerts should be combined with clear institutional clinical practice guidelines or care bundles outlining the most appropriate response to the level of the e-alert.

A number of clinical audits of patients with AKI have identified deficiencies in the identification, documentation and intervention [47, 48]. Among others, these include failure to diagnose and document AKI, to adequately assess the patient’s clinical status or to measure urine output and sequential creatinine levels and withhold or dose-adjust nephrotoxic medications.

Comprehensive clinical practice guidelines have been developed by KDIGO, the UK National Clinical Guideline Centre, and other groups, for the recognition and management of patients with AKI [1, 49]. In addition, some healthcare centers have developed AKI care checklists to facilitate early recognition and appropriate management of patients with AKI [26, 50]. Tsui et al. devised an AKI care bundle to guide the clinical response in patients with AKI [50]. The impact of implementing an AKI care bundle was studied in patients with new-onset AKI. This involved a hospital-wide education campaign, although an e-alert system was not used. Improved compliance with appropriate investigations and initial treatments was associated with a decreased requirement for ICU admission and a trend towards a shorter length of stay.

Kohle et al. developed an AKI care bundle and combined this with an e-alert system to notify physicians that their patients may have developed AKI [26]. Outcomes were compared in patients who had the care bundle completed within 24 h of AKI alert versus those who did not. Progression to higher AKI stages was lower in patients in whom the care bundle was implemented within 8 h. These patients also had lower odds of death at discharge and up to 4 months post discharge.

Despite the development of guidelines for the staging and classification of AKI and chronic kidney disease (CKD), kidney disease is poorly documented in physician notes, suggesting both lack of recognition and understanding of the importance of documentation for diagnostic coding in administrative databases and institutional reimbursement [51, 52]. Consequently, following receipt of an AKI e-alert and assessment of the patient, the physician who has been notified should document the presence of the appropriate AKI stage in the patient’s file, problem list, and EHR. Consideration should be given to the automatic exportation of this data to the institutional administrative, and diagnostic coding system.

The minimal clinical response to an e-alert suggesting the presence or risk of AKI should be a full clinical and laboratory reassessment of the patient as well as a review of all medications by the provider receiving the e-alert.

Following the appropriate design of e-alert systems, effective utilization of change management tools and educating all stakeholders determines the success of e-alerts. In the first step, awareness of the need to such e-alert systems needs to be raised. Investigators and clinicians must conduct studies to show improvement in the processes of care or patient clinical outcomes, utilizing such systems. In this stage, communication with all stakeholders and asking them for their input is essential. In the next phase, desire to participate and support using these tools need to be instigated among all clinicians and care providers. Providing incentives to the e-alert targets would increase the chance of e-alert implementation success. Some of these incentives are an enhancement in patient safety and quality of care, easing the information overload and increasing hospital income by appropriate documentation. Following raising awareness and creating a desire to participate, stakeholders need to be educated on the use of e-alerts and clinical decision support systems. In this phase, some examples of best practices could be catered to the clinicians to be used as role models. Constant coaching and mentoring, and removing the bottlenecks are steps need to be taken to the next stage. And finally, e-alert utilization should be reinforced by continuous supplement of appropriate information regarding improvement in patient outcomes or hospital reimbursement, and even enhanced physician reputation. Care providers then are encouraged to improve their effort in the implementation of e-alert systems. Change management tools like ADKAR (Awareness, Desire, Knowledge, Ability, and Reinforcement) should be considered for successful implementation of a well-designed and targeted e-alert [53].

Conclusion

The current evidence for e-alert system efficacy and effectiveness, although growing, remains insufficient. Technology-related and human factors are crucial elements of any future investigation or implementation of such tools. Implementation of such systems should not be done without a vigorous plan to evaluate the efficacy and effectiveness of e-alerts. Efficacy and effectiveness of e-alerts should be measured by context-specific process and logistical outcomes. The evidence-based clinical decision support that should be considered following successful e-alert implementation include but not limited to appropriate documentation of AKI, ordering context specific tests, evaluation of etiology and providing context specific management and therapeutic options.

Abbreviations

- ADQI:

-

Acute Dialysis Quality Initiative

- AKI:

-

Acute Kidney Injury

- AKIN:

-

Acute Kidney Injury Network

- CDS:

-

Clinical Decision Support

- CKD:

-

Chronic Kidney Disease

- e-alert:

-

electronic-alert

- KDIGO:

-

Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes

- RIFLE:

-

Risk, Injury, Failure, Loss, End-stage renal disease definition for AKI

References

Kidn disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Acute Kidney Injury Work Group. KDIGO Clinical practice guideline for acute kidney injury. Kidney Int. 2012;2:1–138.

Bellomo R, Ronco C, Kellum JA, Mehta RL, Palevsky P. Acute renal failure - definition, outcome measures, animal models, fluid therapy and information technology needs: the Second International Consensus Conference of the Acute Dialysis Quality Initiative (ADQI) Group. Crit Care. 2004;8:R204–12.

Mehta RL, Kellum JA, Shah SV, Molitoris BA, Ronco C, Warnock DG, et al. Acute Kidney Injury Network: report of an initiative to improve outcomes in acute kidney injury. Crit Care. 2007;11:R31.

Thomas ME, Blaine C, Dawnay A, Devonald MA, Ftouh S, Laing C, et al. The definition of acute kidney injury and its use in practice. Kidney Int. 2015;87:62–73.

Kellum JA, Bellomo R, Ronco C. Acute Dialysis Quality Initiative (ADQI): methodology. Int J Artif Organs. 2008;31:90–3.

Colpaert K, Hoste E, Van Hoecke S, Vandijck D, Danneels C, Steurbaut K, et al. Implementation of a realtime electronic alert based on the RIFLE criteria for acute kidney injury in ICU patients. Acta Clin Belg Suppl. 2007;2:322–5.

Thomas M, Sitch A, Dowswell G. The initial development and assessment of an automatic alert warning of acute kidney injury. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2011;26:2161–8.

Selby NM, Crowley L, Fluck RJ, McIntyre CW, Monaghan J, Lawson N, et al. Use of Electronic Results Reporting to Diagnose and Monitor AKI in Hospitalized Patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;7:533–40.

Porter CJ, Juurlink I, Bisset LH, Bavakunji R, Mehta RL, Devonald MA. A real-time electronic alert to improve detection of acute kidney injury in a large teaching hospital. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2014;29:1888–93.

Handler SM, Cheung PW, Culley CM, Perera S, Kane-Gill SL, Kellum JA, et al. Determining the incidence of drug-associated acute kidney injury in nursing home residents. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2014;15:719–24.

Wallace K, Mallard AS, Stratton JD, Johnston PA, Dickinson S, Parry RG. Use of an electronic alert to identify patients with acute kidney injury. Clin Med. 2014;14:22–6.

Ahmed A, Vairavan S, Akhoundi A, Wilson G, Chiofolo C, Chbat N et al. Development and validation of electronic surveillance tool for acute kidney injury: A retrospective analysis. J Crit Care. 2015.

Sellier E, Colombet I, Sabatier B, Breton G, Nies J, Zapletal E, et al. Effect of alerts for drug dosage adjustment in inpatients with renal insufficiency. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2009;16:203–10.

Thomas ME, Sitch A, Baharani J, Dowswell G. Earlier intervention for acute kidney injury: evaluation of an outreach service and a long-term follow-up. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2015;30:239–44.

Wilson FP, Shashaty M, Testani J, Aqeel I, Borovskiy Y, Ellenberg SS, et al. Automated, electronic alerts for acute kidney injury: a single-blind, parallel-group, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2015;385:1966–74.

Rind DM, Safran C, Phillips RS, Slack WV, Calkins DR, Delbanco TL et al. The effect of computer-based reminders on the management of hospitalized patients with worsening renal function. Proc Annu Symp Comput Appl Med Care. 199128–32.

Rind DM, Safran C, Phillips RS, Wang Q, Calkins DR, Delbanco TL, et al. Effect of computer-based alerts on the treatment and outcomes of hospitalized patients. Arch Intern Med. 1994;154:1511–7.

Chertow GM, Lee J, Kuperman GJ, Burdick E, Horsky J, Seger DL, et al. Guided medication dosing for inpatients with renal insufficiency. JAMA. 2001;286:2839–44.

McCoy AB, Waitman LR, Gadd CS, Danciu I, Smith JP, Lewis JB, et al. A Computerized Provider Order Entry Intervention for Medication Safety During Acute Kidney Injury: A Quality Improvement Report. Am J Kidney Dis. 2010;56:832–41.

Terrell KM, Perkins AJ, Hui SL, Callahan CM, Dexter PR, Miller DK. Computerized decision support for medication dosing in renal insufficiency: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Emerg Med. 2010;56:623–9.

Cho A, Lee JE, Yoon JY, Jang HR, Huh W, Kim YG, et al. Effect of an electronic alert on risk of contrastinduced acute kidney injury in hospitalized patients undergoing computed tomography. Am J Kidney Dis. 2012;60:74–81.

Colpaert K, Hoste EA, Steurbaut K, Benoit D, Van Hoecke S, De Turck F, et al. Impact of real-time electronic alerting of acute kidney injury on therapeutic intervention and progression of RIFLE class. Crit Care Med. 2012;40:1164–70.

Goldstein SL, Kirkendall E, Nguyen H, Schaffzin JK, Bucuvalas J, Bracke T, et al. Electronic health record identification of nephrotoxin exposure and associated acute kidney injury. Pediatrics. 2013;132:e756–67.

Selby NM. Electronic alerts for acute kidney injury. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2013;22:637–42.

Claus BO, Colpaert K, Steurbaut K, De Turck F, Vogelaers DP, Robays H, et al. Role of an electronic antimicrobial alert system in intensive care in dosing errors and pharmacist workload. Int J Clin Pharm. 2015;37:387–94.

Kolhe NV, Staples D, Reilly T, Merrison D, Mcintyre CW, Fluck RJ, et al. Impact of Compliance with a Care Bundle on Acute Kidney Injury Outcomes: A Prospective Observational Study. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0132279.

Glassman PA, Simon B, Belperio P, Lanto A. Improving recognition of drug interactions: benefits and barriers to using automated drug alerts. Med Care. 2002;40:1161–71.

Magnus D, Rodgers S, Avery AJ. GPs’ views on computerized drug interaction alerts: questionnaire survey. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2002;27:377–82.

Feldstein A, Simon SR, Schneider J, Krall M, Laferriere D, Smith DH, et al. How to design computerized alerts to safe prescribing practices. Jt Comm J Qual Saf. 2004;30:602–13.

Spina JR, Glassman PA, Belperio P, Cader R, Asch S, Primary CIGOTVALAHS. Clinical relevance of automated drug alerts from the perspective of medical providers. Am J Med Qual. 2005;20:7–14.

Steele AW, Eisert S, Witter J, Lyons P, Jones MA, Gabow P, et al. The effect of automated alerts on provider ordering behavior in an outpatient setting. PLoS Med. 2005;2:e255.

Smith DH, Perrin N, Feldstein A, Yang X, Kuang D, Simon SR, et al. The impact of prescribing safety alerts for elderly persons in an electronic medical record: an interrupted time series evaluation. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1098–104.

van der Sijs H, Aarts J, Vulto A, Berg M. Overriding of drug safety alerts in computerized physician order entry. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2006;13:138–47.

Shah NR, Seger AC, Seger DL, Fiskio JM, Kuperman GJ, Blumenfeld B, et al. Improving acceptance of computerized prescribing alerts in ambulatory care. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2006;13:5–11.

Weingart SN, Simchowitz B, Shiman L, Brouillard D, Cyrulik A, Davis RB, et al. Clinicians’ assessments of electronic medication safety alerts in ambulatory care. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:1627–32.

Payne TH, Hines LE, Chan RC, Hartman S, Kapusnik-Uner J, Russ AL, et al. Recommendations to improve the usability of drug-drug interaction clinical decision support alerts. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2015;22:1243–50.

Phansalkar S, Edworthy J, Hellier E, Seger DL, Schedlbauer A, Avery AJ, et al. A review of human factors principles for the design and implementation of medication safety alerts in clinical information systems. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2010;17:493–501.

Kesselheim AS, Cresswell K, Phansalkar S, Bates DW, Sheikh A. Clinical decision support systems could be modified to reduce ‘alert fatigue’ while still minimizing the risk of litigation. Health Aff (Millwood). 2011;30:2310–7.

Seidling HM, Phansalkar S, Seger DL, Paterno MD, Shaykevich S, Haefeli WE, et al. Factors influencing alert acceptance: a novel approach for predicting the success of clinical decision support. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2011;18:479–84.

Phansalkar S, van der Sijs H, Tucker AD, Desai AA, Bell DS, Teich JM, et al. Drug-drug interactions that should be non-interruptive in order to reduce alert fatigue in electronic health records. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2013;20:489–93.

Embi PJ, Leonard AC. Evaluating alert fatigue over time to EHR-based clinical trial alerts: findings from a randomized controlled study. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2012;19:e145–8.

Lee EK, Mejia AF, Senior T, Jose J. Improving Patient Safety through Medical Alert Management: An Automated Decision Tool to Reduce Alert Fatigue. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2010;2010:417–21.

Anderson HJ. Avoiding ‘alert fatigue’. Health Data Manag. 2009;17:42.

Lin J, Fernandez H, Shashaty MG, Negoianu D, Testani JM, Berns JS, et al. False-Positive Rate of AKI Using Consensus Creatinine-Based Criteria. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;10:1723–31.

Hoste EA, Bagshaw SM, Bellomo R, Cely CM, Colman R, Cruz DN, et al. Epidemiology of acute kidney injury in critically ill patients: the multinational AKI-EPI study. Intensive Care Med. 2015;41:1411–23.

Sood MM, Shafer LA, Ho J, Reslerova M, Martinka G, Keenan S, et al. Early reversible acute kidney injury is associated with improved survival in septic shock. J Crit Care. 2014;29:711–7.

NCEPOD. Adding insult to injury 2009.

Aitken E, Carruthers C, Gall L, Kerr L, Geddes C, Kingsmore D. Acute kidney injury: outcomes and quality of care. QJM. 2013;106:323–32.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Acute Kidney Injury: Prevention, detection and management of acute kidney injury up to the point of renal replacement therapy. NICE guidelines (CG 169). 2013

Tsui A, Rajani C, Doshi R, De Wolff J, Tennant R, Duncan N, et al. Improving recognition and management of acute kidney injury. Acute Med. 2014;13:108–12.

Vlasschaert ME, Bejaimal SA, Hackam DG, Quinn R, Cuerden MS, Oliver MJ, et al. Validity of administrative database coding for kidney disease: a systematic review. Am J Kidney Dis. 2011;57:29–43.

Shirazian S, Wang R, Moledina D, Liberman V, Zeidan J, Strand D, et al. A pilot trial of a computerized renal template note to improve resident knowledge and documentation of kidney disease. Appl Clin Inform. 2013;4:528–40.

Hiatt J. ADKAR: a model for change in business, government, and our community. 1st ed. Loveland: Prosci Learning Center Publications; 2006.

Acknowledgements

ᅟ

ADQI 15th Consensus Meeting Contributors

Sean M. Bagshaw, Division of Critical Care Medicine, Faculty of Medicine and Dentistry, University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB, Canada

Rajit Basu, Division of Critical Care and the Center for Acute Care Nephrology, Department of Pediatrics, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, Cincinnati, OH, USA

Azra Bihorac, Division of Critical Care Medicine, Department of Anesthesiology, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL, USA

Lakhmir S. Chawla, Departments of Medicine and Critical Care, George Washington University Medical Center, Washington, DC, USA

Michael Darmon, Department of Intensive Care Medicine, Saint-Etienne University Hospital, Saint-Priest-En-Jarez, France

R.T. Noel Gibney, Division of Critical Care Medicine, Faculty of Medicine and Dentistry, University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB, Canada

Stuart L. Goldstein, Department of Pediatrics, Division of Pediatric Nephrology, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, Cincinnati, OH, USA

Charles E. Hobson, Department of Health Services Research, Management and Policy, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL, USA

Eric Hoste, Department of Intensive Care Medicine, Ghent University Hospital, Ghent University, Ghent, Belgium, and Research Foundation – Flanders, Brussels, Belgium

Darren Hudson, Division of Critical Care Medicine, Faculty of Medicine and Dentistry, University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB, Canada

Raymond K. Hsu, Department of Medicine, Division of Nephrology, University of California San Francisco, San Francisco, CA, USA

Sandra L. Kane-Gill, Departments of Pharmacy, Critical Care Medicine and Clinical Translational Sciences, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, USA

Kianoush Kashani, Divisions of Nephrology and Hypertension, Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, Department of Medicine, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, USA

John A. Kellum, Center for Critical Care Nephrology, Department of Critical Care Medicine, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, USA

Andrew A. Kramer, Prescient Healthcare Consulting, LLC, Charlottesville, VA, USA

Matthew James, Departments of Medicine and Community Health Sciences, Cumming School of Medicine, University of Calgary, Calgary, Canada

Ravindra Mehta, Department of Medicine, UCSD, San Diego, CA, USA

Sumit Mohan, Department of Medicine, Division of Nephrology, College of Physicians & Surgeons and Department of Epidemiology Mailman School of Public Health, Columbia University, New York, NY, USA

Hude Quan, Department of Community Health Sciences, Cumming School of Medicine, University of Calgary, Calgary, Canada

Claudio Ronco, Department of Nephrology, Dialysis and Transplantation, International Renal Research Institute of Vicenza, San Bortolo Hospital, Vicenza, Italy

Andrew Shaw, Department of Anesthesia, Division of Cardiothoracic Anesthesiology, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN, USA

Nicholas Selby, Division of Health Sciences and Graduate Entry Medicine, School of Medicine, University of Nottingham, UK

Edward Siew, Department of Medicine, Division of Nephrology, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN, USA

Scott M. Sutherland, Department of Pediatrics, Division of Nephrology, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, USA

F. Perry Wilson, Section of Nephrology, Program of Applied Translational Research, Yale University School of Medicine, and Veterans Affairs Medical Center, New Haven, CT, USA

Hannah Wunsch, Department of Critical Care Medicine, Sunnybrook Health Sciences Center and Sunnybrook Research Institute; Department of Anesthesia and Interdepartmental Division of Critical Care, University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada

Continuing medical education

The 15th ADQI Consensus Conference held in Banff, Canada on September 6-8th, 2015 was CME accredited Continuing Medical Education and Professional Development, University of Calgary, Calgary, Canada.

Financial support

Funding for the 15th ADQI Consensus Conference was provided by unrestricted educational support from: Division of Critical Care Medicine, Faculty of Medicine and Dentistry, and the Faculty of Medicine and Dentistry, University of Alberta (Edmonton, AB, Canada); Center for Acute Care Nephrology, Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center (Cincinnati, OH, USA); Astute Medical (San Diego, CA, USA); Baxter Healthcare Corp (Chicago, IL, USA); Fresenius Medical Care Canada (Richmond Hill, ON, Canada); iMDsoft Inc (Tel Aviv, Israel); La Jolla Pharmaceutical (San Diego, CA, USA); NxStage Medical (Lawrence, MA, USA); Premier Inc (Charlotte, NC, USA); Philips (Andover, MA, USA); Spectral Medical (Toronto, ON, Canada).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

EH, KK, PW, and NG drafted the first version of the manuscript. This draft was corrected for content by all authors. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Hoste, E.A.J., Kashani, K., Gibney, N. et al. Impact of electronic-alerting of acute kidney injury: workgroup statements from the 15th ADQI Consensus Conference. Can J Kidney Health Dis 3, 10 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40697-016-0101-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40697-016-0101-1