Abstract

Background

Many barrel or columnar cacti, including some in the Atacama Desert, produce their reproductive tissue at or near the terminal apices of solitary or minimally branched stems that lean toward the equator, reportedly to maximize exposure to photosynthetically active radiation (PAR). Those with lateral reproductive tissue, often produce the tissue on the equatorial side of the stems. An examination of the multi-stemmed, arbuscular cactus, Eulychnia breviflora, was made to determine if it follows the same general strategy.

Methods

Individuals of the species were evaluated along a 100 km transect in the Atacama Desert. The position of all floral buds and open flowers was documented relative to the center of the plants and relative to the center of the individual stems on which they were located.

Results

A highly significant majority of the reproductive tissue was located on the equatorial (north) side of the plant and on the equatorial (north) side of the stems on which it was found.

Conclusion

Our explanation of the phenomenon differs from other researchers. Inasmuch as reproductive tissue contains little or no chlorophyll, we suggest that the flowers emerge from areas of the stems that receive abundant PAR, not because the reproductive tissue itself requires exposure to PAR. Because the translocation of photosynthates in cacti is difficult and energetically expensive, positioning of reproductive tissue in zones of the stems with high photosynthetic capacity is more energetically efficient. In addition, the Atacama Desert is not particularly warm. Exposure of flowers to solar radiation may produce a thermal reward for pollinators, in addition to any nectar rewards received.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The Atacama Desert covers a strip approximately 1000 km long in northern Chile, extending southward from the city of Arica, near the border with Peru at approximately 18° 24’ S Latitude, to near the city of La Serena at approximately 29° 55’ S Latitude. The desert extends eastward, beginning at the Pacific coast, to an elevation of approximately 1500 m near the base of the Andes Mountains [4]. The width of the desert varies, but averages less than 100 km. Average annual precipitation ranges from less than 1 mm near Arica to approximately 70 mm near La Serena, making it one of the driest places on Earth [7]. Various factors contribute to the aridity: (1) the Atacama Desert is characterized by a significant rain shadow effect created as the easterly winds rise to cross the Andes Mountains in the east, (2) the desert lies in the high pressure zone where the descending cool, dry air masses of the atmospheric Hadley and Ferrel cells converge, and (3) the surface of the adjacent Pacific Ocean is characterized by cool temperatures brought by the Humboldt Current from Antarctica [26, 31]. As a consequence, aridity in the region has existed for some 34 Ma, and hyperaridity has prevailed for 15–25 Ma [12, 32, 37]. Despite the extreme aridity, a fog zone exists in the narrow strip near where the desert reaches the coast. Semi-regular fog banks, known locally as camanchaca, roll in from the Pacific Ocean. Many of the plants that persist in the western Atacama Desert derive the bulk of the moisture needed for survival and reproduction from condensation of the camanchaca [6, 38, 41]. Although the camanchaca may occur in any season and at any time of day, it is most prevalent at night during the winter months in the north [8], but in the springtime in the south [20]. It is generally limited to an elevational range between 650 and 1200 m above sea level, and frequently leads to the formation of unique fog oases, known as lomas, that are characterized by unusually high vegetative diversity and endemism [7, 41, 47].

While visiting the Parque Nacional Pan de Azúcar (Sugarloaf National Park) in the Atacama Desert, we observed an unusual growth form in some cacti of the region. Ehleringer et al. [14] previously described the columnar or barrel cacti of the genus Copiapoa as leaning to the north (equatorially) in the Atacama Desert. Because the area lies south of the Tropic of Capricorn, the point at which the sun reaches its southernmost zenith, the sun is present at various distances to the north all year long. Hence, by leaning to the north, the cacti ensure that their reproductive tissue, located at the apices of the stems, maximizes direct exposure to sunlight. While in the National Park for an unrelated project, we observed several shorter species of Copiapoa that exhibited that trait. On our return southward toward La Serena, the southernmost city of the Atacama Desert, we saw what we first assumed to be a much taller species of Copiapoa. On closer inspection, we determined that it was Eulychnia breviflora Phil., an endemic multi-stemmed, arbuscular or shrub-like species of cactus known locally as copao. The flowers and flower buds were located predominantly along the sides of the stems rather than at the apices. Based on our observations, we hypothesized that the species was able to maximize exposure of its reproductive tissue to direct solar radiation, not by leaning toward the equator, but by producing floral structures on stems that grew on the equatorial side of the plants, and on the equatorial side of those stems. Here, we report the findings of a subsequent visit during which we collected field data from a large number of plants over a wider geographic area.

Methods

As we traveled southward from the Parque Nacional Pan de Azucar on a subsequent visit, we observed large numbers of individuals of Eulychnia breviflora beginning at approximately 27° 43’ 668” S Latitude, 70° 58’ 634” W Longitude, not far from the town of Bahía Inglesa. We continued on a marginally improved road for approximately 100 km, stopping periodically when we observed healthy individuals of E. breviflora, thus creating a 100 km transect. We recorded all flower buds or open flowers present on randomly selected plants. On each plant, we recorded the position of the reproductive organs relative to the center of the plant, and relative to the center of the individual stems on which they were located.

Statistical analyses were subsequently completed using R [36], and the R package ‘circular’ [2]. To evaluate the research hypothesis, a Rayleigh test for unimodal departures from uniformity was conducted [28]. Next, a Watson’s test for Goodness of Fit for a von Mises distribution was conducted for both responses. The von Mises distribution is described in [28] and is given by f(θ) = e κ cos(θ − μ)/2πI 0(κ) where θ, μ ∈ [0, 2π] and κ > 0. This distribution is commonly used to assess unimodal circular distributions because of its tractability and analogous relationship to the linear normal distribution [17]. The von Mises distribution has two parameters, a location parameter μ and a dispersion or concentration parameter κ that can be considered analogous to the standard error in a linear normal distribution. This distribution function contains a modified Bessel function of the first kind I 0(κ) that requires the likelihood to be evaluated by numerical integration.

Before a test of difference in location between the two position types could be conducted, the difference in concentration between each was assessed. This is comparable to a two sample t-test where one must consider an alternate form of the test when the variance estimates between the two samples are different. Fisher’s test of common concentration was used to assess differences in κ since the position types are both from von Mises distributions [17]. The test statistic is distributed as F with g-1, N-g degrees of freedom, where g = 2 is the number of groups and N = 359 is the total sample size of all groups.

To test for differences in common mean direction between the two position types, a Watson’s large sample nonparametric test was used [17]. This test is potentially less powerful than the Watson-Williams Test for homogenous directions between two von Mises distributions [46]. However, the former was used because the concentrations between the two types are different, whereas the latter assumes equal concentrations. The test statistic is distributed as χ2 with g-1 degrees of freedom.

Results

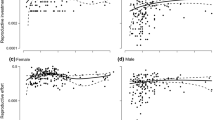

By the time we completed the 100 km transect, we had documented the location of 180 flowers or flower buds on 40 different plants of E. breviflora. Figure 1 suggests unimodal symmetric distributions of the reproductive organs relative to the center of the plants and relative to the center of the stems on which they were growing. The vast majority of the buds and/or flowers were located on the north (equatorial) side of the plants (Fig. 1a). They were also largely located on the north (equatorial) side of the stems on which they were found (Fig. 1b). Rayleigh tests for the two position categories indicate non-uniform distributions (p < 0.01) for both. Watson’s Goodness of Fit tests indicate that both samples were drawn from von Mises distributions (p > 0.05 for both). Von Mises maximum likelihood estimates for both samples are shown in Table 1.

Circular empirical distribution of the reproductive tissue (floral buds and flowers) relative to: a the center of the plant, and b the center of the individual stems on which they were located. The distributions are depicted as circular histograms with inner rose diagrams along with kernel density estimates for each of the two position types

The Fisher test indicated a significant difference in concentration parameters between the two position types at α = 0.05 (F 1,357 = 14.06, p = 0.0002). Watson’s test indicated that mean directions were significantly different at α = 0.05 (χ 21 = 4.38, p = 0.036). The average position of the reproductive tissue relative to the center of the stems on which they grew (5°) was not significantly different from north. The position of the reproductive structures relative to the center of the plants was centered slightly but significantly east of north at approximately 24°.

Discussion

Reproduction is energetically expensive [23], and the amount of energy that plants can afford to devote to reproduction is limited [3]. This can be especially critical in arid areas where water is a scarce resource [39]. Plants have evolved a variety of strategies to cope with aridity [16]. Average annual precipitation at Bahía Inglesa, where we began the transect, averages only 58 mm, falling primarily during the winter months of June–August (Climate-Data.org/location/498309/). While the Atacama Desert is classified as hyperarid, it is also considered to be a cool desert. Temperatures at Bahia Inglesa range from approximately 13 °C in the winter to about 20 °C in the summer.

Various cacti have reportedly evolved structural and morphological strategies to maximize the exposure of their reproductive tissue to photosynthetically active radiation (PAR). Many columnar and barrel cacti are known to produce flowers in cephalia or pseudocephalia at or near the terminal apices of solitary or minimally branched stems that lean toward the equator [13, 14, 21, 33, 43, 44, 48]. Other columnar cacti produce their flowers and fruits along the sides of the stems that face the equator, thus accomplishing the same effect of maximizing exposure to PAR [1, 10, 15, 29, 42]. Although Ehleringer et al. [14] noted equatorial tilting of stems of the columnar cactus genus Copiapoa in the Atacama Desert, presumably as a mechanism to orient the cephalia toward the equator in order to maximize exposure to PAR, very few researchers have explored the phenomenon for non-columnar cacti. Notably, the stems of the arbuscular Eulychnia breviflora do not tilt notably; this species produces reproductive tissue primarily on the sides of stems located on the equatorial side of the plant, and on the equatorial side of those stems.

Notably, while flowers of E. breviflora were generally oriented toward the equator, the equatorial orientation was stronger relative to the center of the stems than relative to the center of the plants. Indeed, relative to the center of the plants, orientation averaged somewhat east of north. Flowers of E. breviflora may emerge from any stem, depending on the level of exposure of the equatorial side of the stem to direct sunlight. Because of the somewhat open structure of the canopy, even the north side of stems located on the south side of the plant may receive sufficient PAR to produce occasional flowers. We have noted a similar slightly eastward orientation of some non-cactus desert plants in North America (unpublished data).

Reproductive tissue is not known to contain chlorophyll or to be involved in photosynthesis to any notable degree. Therefore, the question reasonably arises as to why the reproductive tissue needs to be exposed to large quantities of PAR. In short, we suggest that it does not. It is known that the translocation of photosynthates laterally between regions of a single cactus stem is difficult, energetically costly, and uncommon [15, 18, 42]. We suggest, therefore, that the reproductive tissue arises from regions of the stems that receive adequate direct exposure to PAR, and where the cost of translocating the photosynthates is minimized by close proximity to the reproductive tissue. Higher levels of PAR interception in photosynthetic regions of the stem is almost assuredly associated with more resources available for reproduction in nearby reproductive tissue, whether it translates into more flowers or seeds, or greater seed viability. Nocturnal CO2 uptake is also correlated with greater stomatal conductance in regions of cactus plants that receive high PAR [19, 42].

Another potential benefit of producing flowers in positions that maximize exposure to direct sunlight, relates to potential thermal rewards for pollinators [9], in addition to any nectar rewards. Flowers of E. breviflora are known to be visited, in descending order of frequency, by bee, fly and beetle pollinators [40]. Bees are able to regulate their internal temperature by vibrating their wings, while beetles and flies depend mostly on radiant or reflected solar energy [45]. Although the climate of the Atacama Desert is relatively cool, the predominant pollinator group (bees) is less dependent on a thermal reward for their pollinating activity than the less frequent pollinators (flies and beetles), which depend on direct, reflected or re-radiated solar energy.

While there may be abundant pollinators, there is still the risk of inadequacy of other resources. Among the likely resource deficiencies that may lead to flower or fruit abortion in a hyperarid desert is water [5, 11]. By aborting reproductive structures early, the plants avoid the unnecessary cost of maintaining structures that will not benefit the plant in the long term [27, 34]. Other potential factors that may lead to the abortion of reproductive structures in some cacti include inadequate or incompatible pollen [24, 35], and insect damage [25, 30]. While we chose to record only healthy flower buds that exhibited the promise of maturing to the flower stage, we did note that approximately 5–10 % of the buds present had been aborted or were in the process of being aborted. The abortion of buds and flowers is not necessarily negative, inasmuch as the overall fecundity of the plant may be enhanced [22].

Conclusions

Our research hypothesis was confirmed, i.e., reproductive tissue (flower buds and open flowers) of Eulychnia breviflora, an endemic, arbuscular cactus of the hyperarid Atacama Desert, was present nearly always on the equatorial (north) side of the plants and on the equatorial side of the individual stems on which they were located. Such orientation of the reproductive tissue, places it adjacent to areas of the stems that receive maximum exposure to PAR, thus minimizing the energetic cost of translocating photosynthates. In addition to nectar, pollinating insects in this cool desert may also be attracted to the flowers of this species due to the potential thermal reward from flowers that receive abundant solar radiation.

References

Aguilar-Gastellum I, Molina-Freaner F. Orientación de las flores de dos poblaciones norteñas de Pachycereus pecten-aboriginum (Cactaceae). Bot Sci. 2015;93:241–7.

Agostinelli C, Lund U. R package ‘circular’: Circular Statistics (version 0.4-3). 2011. https://r-forge.r-project.org/projects/circular/. Accessed 17 November 2015.

Bell G. The costs of reproduction and their consequences. Am Nat. 1980;116:45–76.

Börgel R. The coastal desert of Chile. In: Amiran DHK, Wilson AW, editors. Coastal deserts: their natural and human environments. Tucson: University of Arizona Press; 1973. p. 111–4.

Bowers JE. More flowers or new cladodes? Environmental correlates and biological consequences of sexual reproduction in a Sonoran Desert prickly pear cactus, Opuntia engelmannii. Bull Torrey Bot Club. 1996;123:34–40.

Cáceres L, Gómez-Silva B, Garró X, Rodríquez V, Monardes V, McKay CP. Relative humidity patterns and fog water precipitation in the Atacama Desert and biological implications. J Geophys Res. 2007;112, G04S14, doi:10.1029/2006JG000344.

Cereceda P, Larrain H, Osses P, Farías M, Egaña I. The climate of the coast and fog zone in the Tarapacá region, Atacama Desert. Chile Atmos Res. 2008;87:301–11.

Cereceda P, Larrain H, Osses P, Farías M, Egaña I. The spatial and temporal variability of fog and its relation to fog oases in the Atacama Desert. Chile Atmos Res. 2008;87:312–23.

Cooley JR. Floral heat rewards and direct benefits to insect pollinators. Ann Entomol Soc Am. 1995;88:576–9.

Córdova-Acosta E, Vite F, Valverde PL. Efecto de la orientación y caracteres de las flores en el éxito reproductivo de Pachycereus weberi en la region de Tehuacán-Cuicatlán. Bol Soc Latin Carib Cact Suc. 2012;9(1):7–8.

De la Barrera E, Nobel PS. Carbon and water relations for developing fruits of Opuntia ficus-indica (L.) Miller, including effects of drought and gibberellic acid. J Exp Bot. 2004;55:719–29.

Dunai TJ, González López GA, Juez-Larré J. Oligocene-Miocene age of aridity in the Atacama Desert revealed by exposure dating of erosion-sensitive landforms. Geology. 2005;33:321–4.

Ehleringer J, House D. Orientation and slope preference in barrel cactus (Ferocactus acanthodes) at its northern distribution limit. Great Basin Nat. 1984;44:133–9.

Ehleringer J, Mooney HA, Gulmon SJ, Rundel P. Orientation and its consequences for Copiapoa (Cactaceae) in the Atacama Desert. Oecologia. 1980;16:63–7.

Figueroa-Castro DM, Valverde PL. Flower orientation in Pachycereus weberi (Cactaceae): effects on ovule production, seed production and seed weight. J Arid Environ. 2011;73:1214–7.

Fischer RA, Turner NC. Plant productivity in the arid and semiarid zones. Annu Rev Plant Physiol. 1978;29:277–317.

Fisher NI. Statistical Analysis of Circular Data. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 1993.

Geller GN, Nobel PS. Branching patterns of columnar cacti: influences on PAR interception and CO2 uptake. Am J Bot. 1986;73:1193–200.

Geller GN, Nobel PS. Comparative cactus architecture and PAR interception. Am J Bot. 1987;74:998–1005.

Garreaud R, Barichivich J, Christie DA, Maldonado A. Interannual variability of the coastal fog at Fray Jorge relict forests in semiarid Chile. J Geophys Res. 2008;113:G04011. doi:10.1029/2008JG00709.

Herce MF, Martorell C, Alonso-Fernandez C, Boullosa LFVV, Meave JA. Stem tilting in the inter-tropical cactus Echinocactus platyacanthus: an adaptive solution to the trade-off between radiation acquisition and temperature control. Plant Biol. 2014;16:571–7.

Holland JN, DeAngelis DL. Ecological and evolutionary conditions for fruit abortion regulate pollinating seed-eaters and increase plant reproduction. Theor Popul Biol. 2002;61:251–63.

Kunz TH, Orrell KS. Energy costs of reproduction. In: Cleveland C et al., editors. Encyclopedia of energy, vol. 5. Oxford: Elsevier Inc.; 2004. p. 423–42.

Lenzi M, Orth AI. Mixed reproduction systems in Opuntia monacantha (Cactaceae) in southern Brazil. Braz J Bot. 2012;35:49–58.

León de la Luz JL, Domínguez-Cadena R, Medel-Narváez A. Biological characteristics and nutritive value of aborted flowers of the cardón (Pachycereus pringlei, Cactaceae) in Baja California Sur, Mexico. Haseltonia. 2002;9:9–13.

Maliva RG, Missimer TM. Aridity and drought. In: Maliva RG, Missimer TM, editors. Arid lands water evaluation and management. Heidelberg: Springer, Berlin; 2012. p. 21–9.

Mandujano MC, Golubov J, Huenneke L. Reproductive ecology of Opuntia macrocentra (Cactaceae) in the northern Chihuahuan Desert. Am Midl Nat. 2013;169:274–85.

Mardia KV, Jupp PE. Directional statistics. 2nd ed. Chichester: Wiley & Sons Ltd.; 2000.

Martínez-Moreno D, Reyes-Matamoros J, Figueroa-Castro DM, Rodríguez-Ramírez T. Efecto de los ácidos orgánicos en la protección de frutos de Pachycereus weberi (J.M. Coult.) Backeb. en el municipio de Santo Domingo, Huehuetlán El Grande, Puebla, México. Rev Iberoam Cien. 2014;1:113–25.

McIntosh ME. Plant size, breeding system, and limits to reproductive success in two sister species of Ferocactus (Cactaceae). Plant Ecol. 2002;162:273–88.

Milich L. Why are deserts dry? 1997. http://ag.arizona.edu/~lmilich/dry.html. Accessed 14 June 2016.

Nishiizumi K, Caffee MW, Finkel RC, Brimhall G, Mote T. Remnants of a fossil alluvial fan landscape of Miocene age in the Atacama Desert of northern Chile using cosmogenic nuclide exposure age dating. Earth Planet Sci Lett. 2005;237:499–507.

Nobel PS. Influence of photosynthetically active radiation on cladode orientation, stem tilting, and height of cacti. Ecology. 1981;62:982–90.

Palleiro N, Mandujano MC, Golubov J. Aborted fruits of Opuntia microdasys (Cactaceae): insurance against reproductive failure. Am J Bot. 2006;93:505–11.

Piña HH, Montaña C, Mandujano MC. Fruit abortion in the Chihuahuan-Desert endemic cactus Opuntia microdasys. Plant Ecol. 2007;193:305–13.

R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. 2014.http://www.R-project.org/. Accessed 14 June 2016.

Rech JA, Currie BS, Michalski G, Cowan AM. Neogene climate change and uplift in the Atacama Desert. Chile Geol. 2006;34:761–4.

Rundel PW, Palma B, Dillon MO, Rasoul Sharifi M, Nilsen ET, Boonpragob K. Tillandsia landbeckii in the coastal Atacama Desert of northern Chile. Rev Chil de Hist Nat. 1997;70:341–9.

Smith SD, Monson RK, Anderson JE. Physiological ecology of North American desert plants. Berlin: Springer; 1997.

Smith-Ramírez C, Yáñez Ramírez K. Digitalización de datos de polinizadores de Chile, interacción insecto-planta y distribución de insectos. Informe Final Técnico y Financiero. Red Interamericana de Información sobre Biodiversidad. 2010.

Thompson MV, Palma B, Knowles JT, Holbrook NM. Multi-annual climate in Parque Nacional Pan de Azúcar, Atacama Desert, Chile. Rev Chil Hist Nat. 2003;76:235–54.

Tinoco-Ojanguren C, Molina-Freaner F. Flower orientation in Pachycereus pringlei. Can J Bot. 2000;78:1489–94.

Valverde PL, Vite F, Pérez-Hernández MA, Zavala-Hurtado JA. Stem tilting, pseudocephalium orientation, and stem allometry in Cephalocereus columna-trajani along a short latitudinal gradient. Plant Ecol. 2007;188:17–27.

Vázquez-Sánchez M, Terrazas T, Arias S. Morphology and anatomy of the Cephalocereus columna-trajani cephalium: why tilting? Plant Systs Evol. 2007;265:87–99.

Warren SD, Harper KT, Booth GM. Elevational distribution of insect pollinators. Am Midl Nat. 1988;120:325–30.

Watson GS, Williams EJ. On the construction of significance tests on the circle and the sphere. Biometrika. 1956;43:344–52.

Westheld A, Klemm O, Grieβbaum F, Sträter E, Larrain H, Osses P, Cereceda P. Fog deposition to a Tillandsia carpet in the Atacama Desert. Anna Geophys. 2009;27:3571–6.

Zavala-Hurtado JA, Vite F, Ezcurra E. Stem tilting and pseudocephalium orientation in Cephalocereus columna-trajani (Cactaceae): a functional interpretation. Ecology. 1998;79:340–8.

Acknowledgements

Salary for SDW and LSB was paid by the U.S. Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. Salary for LEA was paid by the Universidad de La Serena, Chile. Travel and field subsistence for SDW and LEA was paid by the U.S. Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station.

Authors’ contributions

SDW and LEA conceptualized the study and performed all field work. LSB performed statistical analyses. All authors participated in writing and revising the manuscript.

Competing interest

The authors declare that there are no competing interests.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Warren, S.D., Aguilera, L.E. & Baggett, L.S. Directional orientation of reproductive tissue of Eulychnia breviflora (Cactaceae) in the hyperarid Atacama Desert. Rev. Chil. de Hist. Nat. 89, 10 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40693-016-0060-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40693-016-0060-z