Abstract

Background

The Suban area of Curup Rejang Lebong is a tourist region in Bengkulu Province, Indonesia, close to the active Ketaun and Musi faults, which are segments of the Sumatra Fault System (SFS). However, no studies have been conducted in this area to assess how geological structures affect seismic ground motions and contribute to seismic hazard and risk assessment.

Methods

The first study of seismic microzonation in the Suban area of Curup City by ambient noise measurements was conducted at 100 sites, spaced ~ 1 km apart, with 60 min of data acquisition for each site. All microseismic data were processed using the Horizontal to Vertical Spectral Ratios (HVSR) method.

Results

The HVSR method revealed the amplification factors (A0) ranging from 1.23 to 8.26 times, corresponding to natural frequency (f0) variations between 1.24 and 9.67 Hz. About 13% and 55% of the sites show high (6 ≤ A0 ≤ 9) and medium (3 ≤ A0 ≤ 6) amplifications, respectively, predominantly in the western parts of the study area, consistent with a high seismic vulnerability index (Kg). Furthermore, we also estimated the ground shear strain (GSS) of the region using the Kanai method with two large historical earthquakes at the Ketahun segment in 1943 (Mw 7.4) and the Musi segment in 1979 (Mw 6.0). The Kg value is consistent with the GSS values and indicates areas of severe damage during the historic earthquakes.

Conclusions

Thus, the western parts of the Suban region are vulnerable to severe damage from an earthquake. These findings could provide valuable insights for future planning and risk management efforts aimed at minimizing the impact of earthquakes in the Suban region.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

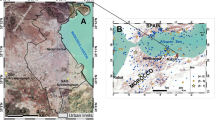

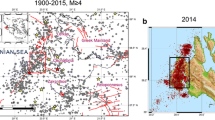

Sumatra Island is the largest island in Indonesia. It is one of the regions in Indonesia that is highly prone to earthquakes due to the three active tectonic zones surrounding it (Fig. 1a). First, there is a subduction zone in the Indian Ocean, the boundary between the India-Australia and Eurasia plates (Natawidjaja 2003; McCaffrey 2009; Rai et al. 2023). This zone can generate earthquakes of relatively large magnitudes, which can trigger tsunamis. Second, the Mentawai fault spans a minimum length of 600 km and is located in the forearc region to the east of the Mentawai Islands (Diament et al. 1992). Third, there is the Sumatran Fault System (SFS) on land. This fault consists of 19 segments stretching along the Bukit Barisan mountain range (Sieh and Natawidjaja 2000) from Banda Aceh in the north to Lampung Province in the south. The SFS can release large earthquakes with a magnitude of Mw > 8, as evidenced by the occurrence of 20 large earthquakes on the SFS in the last 100 years (Haerudin et al. 2020).

Two active segments of the SFS, the Ketaun and the Musi segments, are located in the area of Curup Rejang Lebong area, the district capital in Bengkulu province on the island of Sumatra (Fig. 1a). Historical records show that a major earthquake caused by seismic activity in the Ketaun segment occurred on June 8, 1943, with a magnitude of Mw 7.4. The epicenter of this earthquake was located at 2.8°S and 102.1°E at a depth of 15 km, a distance of 78 km northwest of Curup-Rejang Lebong. About 90% of the residents' houses were heavily damaged. Another earthquake occurred in the Musi segment on December 15, 1979, with a magnitude of Mw 6.0 (Untang et al. 1985; Sieh and Natawidjaja 2000; Hurukawa et al. 2014). The epicenter of this earthquake was located at 3.3°S and 102.5°E with a depth of 33 km, a distance of 13 km northwest of Curup-Rejang Lebong, or 34 km southwest of Kepahiang. The earthquake damaged 90% of the houses in the area (Untang et al. 1985; Sieh and Natawidjaja 2000; Hurukawa et al. 2014). In addition to inland earthquake sources, Curup Rejang Lebong is also vulnerable to seafloor earthquakes from subduction zones and the Mentawai Fault. Despite its seismic vulnerability, the Curup Rejang Lebong area has been developed as a tourism area in Bengkulu as stated in the regional spatial planning policy of Rejang Lebong for 2012–2032 (Pemerintah Kabupaten Rejang Lebong 2012; Hartanto et al. 2022), resulting in rapid economic growth with the construction of many buildings. However, no investigation has been conducted in this area to evaluate how geological structures affect seismic ground motion and contribute to seismic hazard and risk assessment.

Earthquake hazards in Curup-Rejang Lebong can be mitigated through seismic microzonation by studying local site effects. Seismic microzonation focuses on identifying small-scale geological and geomorphological factors at a small scale that have a significant impact on the characteristics of seismic motion. Geological conditions at the shallow surface strongly influence the response of the ground to earthquake activity (Ben-Menahem et al. 1981; Al Yuncha and Luzón 2000). Although soil physical properties can be characterized by traditional methods such as soil drilling, this method is inefficient and require expensive costs (Putti and Satyam 2020). Another option for obtaining effective and efficient information on subsurface geology is to measure ambient noise measurement using microtremor surveys. This measurement is non-destructive and can provide information on internal structures (Panou et al. 2005; Akkaya et al. 2015). The characteristics of various cities that are susceptible to seismic activity have been thoroughly analyzed using microtremor data (Akkaya et al. 2015; Shankar et al. 2021a; Rahayu et al. 2022). The horizontal-to-vertical spectral ratio (HVSR) method can be used to study subsurface ambient noise data. The HVSR technique provides consistent information related to site effects (Ji et al. 2017; Shankar et al. 2021b; Xu and Wang 2021; Shreyasvi and Venkataramana 2022). This method can provide valuable insights can be gained into the dynamic properties of local site characteristics such as natural frequency (f0) and amplification factor (A0). Natural frequency refers to the frequency at which a particular site vibrates most strongly in response to seismic waves, while amplification factor refers to the degree to which ground motion is amplified as it passes through different layers of soil and rock below the surface. Therefore, these parameters can be used to determine the seismic vulnerability score of a particular area to seismic ground motion.

This paper presents the results of the first study of seismic microzonation in the Suban area in Curup Rejang Lebong using ambient noise measurements. Ambient noise measurements were conducted at 100 sites throughout the Suban Curup Rejang Lebong tourism area. The site effect study resulted in a comprehensive microzonation of natural frequency distribution, amplification, seismic vulnerability index, and ground shear strain. Conducting this study is critical for conducting site-specific response studies and for producing a microzonation map of seismic hazard for the Curup region. This map could prove valuable in taking precautionary measures in future construction and development projects.

Data and method

Geological setting and study area

Curup Rejang Lebong is a district in the province of Bengkulu province on the island of Sumatra. The Rejang Lebong Regency is administratively located between 102°19' to 102°57' E and 2°22′07'' to 3°31' S. The area is hilly and lies in the highlands of the Bukit Barisan Mountains, with an elevation ranging from 100 to 1000 m above sea level (Fig. 1b). The Curup Rejang Lebong area is mainly characterized by volcanic debris deposits in the form of volcanic rocks (Fig. 1b), suggesting that the highlands composed of hard rock layers (bedrock) have a thin sedimentary layer (Indarto et al. 2018; Patrisia et al. 2019). This area is also geologically structured by the Southwest Sumatran Fault, which includes two local faults, the 85 km long Ketaun segment and the 70 km long Musi segment (Sieh and Natawidjaja 2000). The slip rate along the Ketaun segment is 9–11 mm/year, while in the Musi segment it is is 15–16 mm/year. Therefore, Curup Rejang Lebong is prone to earthquakes that can damage buildings and cause losses and casualties (Hurukawa et al. 2014).

Ambient noise measurement and processing

Ambient noise measurements in the Suban Curup Rejang Lebong were conducted at 100 sites spaced approximately 1 km apart (Fig. 1b). We have selected the sites based on accessibility and distance from man-made noises. We determined the position of the site using a GPS. Data acquisition and data quality control were performed according to the procedures recommended by the Site Effects Assessment Using Ambient Excitations (SESAME) European Research (SESAME 2004). Acquisitions were made from morning to afternoon in open fields away from ambient noise disturbances to obtain pure microtremors. Any ambient noise such as vehicles, wind, and human activity could affect the amplitude of the vibration. Data were collected using a set of Pasi Mod Gemini Sn-1405 seismometers. Microtremors were recorded for 1 h at a sampling frequency of 5 Hz.

Ambient noise analysis was performed using the HVSR method, following Nakamura (1989). To derive the spectral amplitudes of the north–south (N-S), east–west (E-W), and vertical (V) components of each site, the signal of all three components is separately subjected to a Fast Fourier Transform (FFT). The HVSR is then calculated by dividing the square root of the mean of the N-S and E-W spectra (SNS and SEW, respectively) by the vertical spectrum (SVS), given by

After smoothing the spectra using window averaging technique, the ratios between the spectra were calculated. The smoothed spectral ratio for each site was obtained by averaging all the ratios at a given frequency. From this ratio, the values of natural frequency (f0) and amplification (A0) values were determined. Figure 2 shows an example of the HVSR curve for four sites.

Once the values of f0 and A0 are obtained, these two values are classified into several categories. The A0 are classified into four groups following Jiang et al. (2022) and the f0 values are grouped based on soil classification following Kanai (1983).

The final step is to calculate of the seismic susceptibility index (Kg) and the ground shear strain, GSS (γ). The Kg value can be used to identify the degree of susceptibility of the soil layer to earthquake deformation (Nakamura 2008), given by the equation:

The γ value is the multiplication of the Kg value with the Peak Ground Acceleration (PGA), given by the equation (Nakamura 1997):

The PGA value (α) is calculated by following the Kanai method (Kanai 1966):

The value of α in this study uses the earthquake scenario from historical earthquakes around Curup Rejang Lebong, which occurred along the Ketaun segment on June 8, 1943 with magnitude (M) of Mw 7.4 and along the Ketaun segment on December 15, 1979 (Mw 6.0). The R is the distance between each site and the hypocenter of the historical earthquakes, and Tg is the dominant period of the site measurements.

Results and discussion

Table 1 shows the amplification and natural frequency values for each measurement point. The value of f0 varies between 1.24 and 9.67 Hz and the value of A0 varies between 1.23 -8.26. The spatial distribution of these two parameters is shown in Fig. 3a and b.

Map of a natural frequency and b classification of natural frequency into Type I (6.667–20 Hz), Type II (4–6.67 Hz), Type III (2.5–4 Hz), and Type IV (< 2.5 Hz), following Kanai (1983)

Natural frequency and amplification factor

In Fig. 3a, we can see that f0 is larger towards the east. The lowest f0 of 1.24 Hz was observed at point T91 at an elevation of 716 m in the western part, while the highest value was observed at point T99 at 1169 m in the eastern part of the study area. The distribution of f0 is consistent with the topography and morphological conditions of the study area, which indicate hilly areas in the east. The f0 is related to sediment thickness, with shallower bedrock resulting in higher natural frequency (Parolai et al. 2002). To observe the distribution of sediment thickness, the soil type was classified into Type I (6.667–20 Hz), Type II (4–6.67 Hz), Type III (2.5–4 Hz), and Type IV (< 2.5 Hz), following Kanai (1983) based on the f0 value. Following Jiang et al. (2022), the Type I indicates very thin sediments dominated by hard rock; Type II indicates the medium category (5–10 m); Type III indicates the thick category (10–30 m); and Type IV indicates very thick category sediments. Out of 100 observation sites, the percentage of each type is Type I 25%, Type II 21%, Type III 31%, and Type IV 23%. In general, Type I and Type II are dominant in the eastern region (Fig. 3b). Several sites in the eastern region with high f0 values, such as T99, T100, and T2, are located at elevations of 1169 m, 1063 m, and 963 m elevations, respectively. High f0 values are also observed in the central part of the observation area, such as at T11, located at 852 m elevation. Therefore, high f0 values are observed in most of the eastern part of Suban, which is related to the morphology of the area, which consists of hard rocks (Indarto et al. 2018), and very thin and medium category sediments. The f0 is also related to the geological conditions of the study area (Syaifuddin et al. 2016). Most of the western Suban area has a low f0 value (Type III and IV), except for very few sites that have high f0 such as T86, T96, and T92, which are located at 677 m, 701 m, and 764 m elevation, respectively. Areas with low f0 may have soft rocks and high sediment thickness (Fig. 3b) due to the presence of small valleys in the region. This phenomenon can cause seismic waves to be trapped in the sediment, making the area vulnerable to earthquake disasters caused by the multireflection of waves. Since the lithological units in the study area are uniform (Kaba volcanic), the dominant factor influencing the natural frequency is the geological and topographic conditions.

In Fig. 4a, we show the A0 distribution where most of the Suban area has A0 greater than 3 times. The smallest A0 of 1.23 was observed at point T93 at an elevation of 810 m in the southwestern parts, while the highest value of 8.26 was observed at point T83 at an elevation of 715 m in the western parts of the study area. A high amplification factor indicates that the ground motion is amplified to a greater extent than in other areas, which can lead to more severe shaking and potential damage to structures. Amplification is generally influenced by geological factors such as the degree of deformation and the physical properties of the rocks (Arifin 2014). The study area consists of volcanic deposits (Fig. 1b). The amplification factor is related to the impedance contrast ratio between the sediment layer on the surface and the underlying bedrock (Nakamura 2000). If the impedance contrast for these two layers is high, the amplification value will also be high, and vice versa (Shankar et al. 2021b). Jiang et al. (2022) classified the amplification values as low (A0 < 3), medium (3 ≤ A0 < 6), high (6 ≤ A0 < 9), and very high (A0 ≥ 9). Based on this classification, the percentages of sites with low, medium, high, and very high categories were 32%, 55%, 13%, and 0%, respectively. Thus, most of the Suban area has medium amplification values and no very high categories (Fig. 4b). According to Nakamura (2000), dangerous amplification values are A0 > 3 and correlate with low f0. Out of 100 observation points, 68 had A0 > 3. Out of the 68 points, when grouped based on the f0 values, Type IV (< 2.5) had 16 points, Type III (2.5–4) had 19 points, Type II (4–6.67) had 12 points, and Type I (6.67–20) had 21 points. Areas of high amplification values associated with low natural frequency (Type IV and III) may experience stronger wave reinforcement than areas of low amplification values. In areas with high amplification zones, there is a potential for strong earthquake shaking in the event of an earthquake.

Map of a amplification factor for each site and classification of amplification factor into low (A0 < 3), medium (3 ≤ A0 < 6), high (6 ≤ A0 < 9), and very high (A0 ≥ 9), following Jiang et al. (2022)

Seismic vulnerability index and ground shear strain

Based on the estimated f0 and A0 values, we calculated the seismic vulnerability index (Kg) using Eq. (2). We found that the Kg values are ranged from 0.33 to 25.17 (Table 1 and Fig. 5). To identify zones based on the seismic vulnerability index, Kg values were categorized into low (Kg ≤ 3), moderate (3 < Kg ≤ 5), high (5 < Kg ≤ 10), and very high (Kg > 10), following Akkaya (2020). Based on this category, the percentage of observation points with Kg values in the low, moderate, high, and very high categories were 43%, 24%, 22%, and 11%, respectively, with a distribution shown in Fig. 5b. Areas susceptible to severe earthquake damage occur in alluvial plains with relatively thick sedimentary material (Nakamura (2000). Locations with high and very high Kg values (> 5) are mainly found in the western parts of the study area, where there is relatively thick sedimentation, as indicated by low f0 values (Fig. 3b). The low Kg values (< 3) are concentrated in the eastern hilly areas of hard rock with high f0 values. The Kg value is related to the degree of vulnerability of an area to earthquake damage, with higher values indicating greater risk. Sunardi et al. (2012) found that areas with a seismic vulnerability index greater than 10 in the Graben Bantul area were severe damaged in the 2006 Bantul earthquake. About 60% of the Bantul area is hilly and the Graben area is located on the flank of a fault hill, which is also prone to earthquakes due to the subduction activity of the Indo-Australian and Eurasian plates to the south and the presence of the Opak fault to the east (Buana and Agung 2015). Sunardi et al. (2012) found that hilly areas with a Kg value of less than 2, were not severely damaged. In Curup Rejang Lebong, we identified 11 points with Kg above 10, including T18, T21, T32, T35, T45, T53, T56, T73, T81, and T83 (Fig. 5). These areas should be alerted during earthquakes.

The Kg was compared with the GSS values (γ) for two historical earthquakes around Curup Rejang Lebong, which occurred along the Ketaun segment on June 8, 1943 (Mw 7.4) and along the Musi segment on December 15, 1979 (Mw 6.0). The distribution of GSS values through the earthquake history of the Ketaun Segment in this area ranges from 0.12 × 10–3 to 7.38 × 10–3 (Fig. 6a). Relatively high values are found mainly in the southern and western parts of the study area, making these areas prone to earthquakes, consistent with the Kg (Fig. 5). High GSS values correlate with earthquake damage. According to Ishihara (2021), surface ground deformation that exceeds a value of γ ≅ 10–3 enters a plastic state, and results in γ > 10–2 which can cause significant deformation events such as landslides and collapses. This was demonstrated by the 1943 Mw 7.4 earthquake, which damaged 90% of the buildings in Tes Village. Tes Village is located in the southwestern part of the study area (Sieh and Natawidjaja 2000; Hurukawa et al. 2014). In addition, the distribution of GSS values from the Musi segment earthquake ranges from 0.01 × 10–3 to 0.56 × 10–3. The distribution of relatively high values is mainly found in the western and southwestern parts of the study area (Fig. 6b), which is also consistent with the seismic vulnerability index. The 1979 Mw 6.0 earthquake caused extensive damage to buildings from Curup to Kepahiang area and killed four people (Untang et al. 1985; Sieh and Natawidjaja 2000; Hurukawa et al. 2014). Kepahiang Regency is located in the southwestern part of the study area. Therefore, the results of microzonation by ambient noise measurement are consistent with the GSS calculated from two historical earthquakes in this region.

Conclusions

The results of the first study of seismic microzonation in the Suban Curup Rejang Lebong area using ambient noise measurements show that the western parts of the study area are prone to severe damage from an earthquake. This is indicated by the higher seismic vulnerability index and larger amplification factors with lower natural frequencies than in the eastern part. The obtained seismic microzonation is consistent with the geological factors of Curup Rejang Lebong, which is located in highlands concentrated on hard rocks. As the elevation increases towards the east, the sediment becomes thinner and relatively safe from earthquake damage. The seismic microzonation from ambient noise measurements is consistent with the GSS values calculated for the historic earthquakes along the Ketaun and Musi segments. Areas with high Kg from ambient noise measurements also have high GSS values. This study is the first ambient noise measurement in Curup Rejang Lebong. It is therefore crucial for seismic hazard and risk assessment and earthquake engineering in designing buildings, bridges and other structures that can withstand the effects of earthquakes. In addition, local governments can use this information to develop appropriate building codes and land-use policies that take into account local geological conditions and potential earthquake hazards.

Availability of data and materials

Data are available upon request.

References

Akkaya I, Özvan A, Tapan M, Şengül MA (2015) Determining the site effects of 23 October 2011 earthquake (Van province, Turkey) on the rural areas using HVSR microtremor method. J Earth Syst Sci 124:1429–1443

Al Yuncha Z, Luzón F (2000) On the horizontal-to-vertical spectral ratio in sedimentary basins. Bull Seismol Soc Am 90:1101–1106

Arifin SS (2014) Penentuan Zona Rawan Guncangan Bencana Gempa Bumi Berdasarkan Analisis Nilai Amplifikasi HVSR Mikrotremor dan Analisis Periode Dominan Daerah Liwa dan Sekitarnya. JGE (jurnal Geofis Eksplorasi) 2:30–40

Ben-Menahem A, Singh SJ, Ben-Menahem A, Singh SJ (1981) Representation of seismic sources. Seism Waves Sources pp 151–256

Buana TW, Agung MW (2015) Liquefaction Characteristic Based on Ground Response Linier Equivalent Analysis and Cyclic Stress Concept on Young Merapi Volcanic Deposit in Bantul. J Jap Soc Eng Geo 1–5

Diament M, Harjono H, Karta K et al (1992) Mentawai fault zone off Sumatra: a new key to the geodynamics of western Indonesia. Geology 20:259–262

Haerudin N, Alami F, Yogi IBS (2020) The effect site analysis based on microtremor data using the Horizontal to Vertical Spectral Ratio (HVSR) method in the Bandar Lampung City. In: Journal of Physics: Conference Series. IOP Publishing, p 12075

Hartanto Y, Firmansyah MA, Adhrianti L (2022) Implementation Digital Marketing Pesona 88 Curup in to Build Image for the Decision of Visit Tourist Attraction. In: 4th Social and Humanities Research Symposium (SoRes 2021). Atlantis Press, pp 589–594

Hurukawa N, Wulandari BR, Kasahara M (2014) Earthquake history of the Sumatran fault, Indonesia, since 1892, derived from relocation of large earthquakes. Bull SeismOl Soc Am 104:1750–1762

Indarto S, Zulkarnain I, Setiawan I, et al (2018) Monografi Batuan Volkanik Segmen Selatan Sumatera, Daerah Bengkulu Di Sayap Barat Pegunungan Bukit Barisan. Pros GEOTEKNOLOGI LIPI

Ishihara K (2021) Evaluation of soil properties for use in earthquake response analysis. Geomechanical modelling in engineering practice. Routledge, London, pp 241–275

Ji K, Ren Y, Wen R (2017) Site classification for National Strong Motion Observation Network System (NSMONS) stations in China using an empirical H/V spectral ratio method. J Asian Earth Sci 147:79–94

Jiang C, Yahong D, Huangdong M et al (2022) A microtremor study to reveal the dynamic response of earth fissure site: the case study in Fenwei Basins. China Environ Earth Sci 81:80

Kanai K (1983) Engineering seismology. Tokyo Univ Tokyo Press, Tokyo

Kanai K (1966) Improved Empirical Formula for the Characteristic of Strong Earthquake Motions. In: Proc. Japan Earthq. Engng. Symp.

McCaffrey R (2009) The tectonic framework of the Sumatran subduction zone. Annu Rev Earth Planet Sci 37:345–366

Nakamura Y (1989) A method for dynamic characteristics estimation of subsurface using microtremor on the ground surface. Railw Tech Res Institute, Q Reports 30:

Nakamura Y (1997) Seismic vulnerability indices for ground and structures using microtremor. In: World congress on railway research in Florence, Italy. Citeseer

Nakamura Y (2000) Clear identification of fundamental idea of Nakamura’s technique and its applications. In: Proceedings of the 12th world conference on earthquake engineering. Auckland/New Zealand, pp 1–8

Nakamura Y (2008) On the H/V Spectrum, The 14th World Conference on Earthquake Engineering

Natawidjaja DH (2003) Neotectonics of the Sumatran Fault and paleogeodesy of the Sumatran subduction zone. California Institute of Technology

Panou AA, Theodulidis N, Hatzidimitriou P et al (2005) Ambient noise horizontal-to-vertical spectral ratio in site effects estimation and correlation with seismic damage distribution in urban environment: the case of the city of Thessaloniki (Northern Greece). Soil Dyn Earthq Eng 25:261–274

Parolai S, Bormann P, Milkereit C (2002) New relationships between Vs, thickness of sediments, and resonance frequency calculated by the H/V ratio of seismic noise for the Cologne area (Germany). Bull Seismol Soc Am 92:2521–2527

Patrisia D, Sailah S, Affandi AK (2019) Analysis of seismicity level and return period of bengkulu area earthquake from 1960–2017. In: Journal of Physics: Conference Series. IOP Publishing, p 12053

Pemerintah Kabupaten Rejang Lebong (2012) Rencana Tata Ruang Wilayah Kabupaten Rejang Lebong Tahun 2012–2032 (Rejang Lebong Regional Spatial Plan for 2012–2032). https://bengkulu.bpk.go.id/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/Perda-Nomor-8-Tahun-2012.pdf. Accessed 26 Apr 2023

Putti SP, Satyam N (2020) Evaluation of site effects using HVSR microtremor measurements in Vishakhapatnam (India). Earth Syst Environ 4:439–454

Rahayu T, Nasution Z, Karnawati D (2022) Regional zonation based on seismic vulnerability using local site effect analysis and potential damage to the city of Medan (North Sumatra, Indonesia) due to earthquake. Geoenvironmental Disasters 9:1–11

Rai AK, Malakar S, Goswami S (2023) Active source zones and earthquake vulnerability around Sumatra subduction zone. J Earth Syst Sci 132:66. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12040-023-02070-9

SESAME W (2004) Site-effects assessment using ambient excitations. Guideline for implementation of the H/V spectral ratio technique on ambient vibrations: measurements, processing and interpretation, European Commission-Research General Directorate Project No. Eur Res Proj WP12–Deliverable D23 12

Shankar U, Kumari S, Yadav PK et al (2021a) Microtremor measurements in the India’s holy city, Varanasi for assessment of site characteristics. Quat Int 585:143–151

Shankar U, Yadav PK, Singh AP, Gupta AK (2021b) Evaluation of site-specific characteristics using microtremor measurements in the Gorakhpur city of Uttar Pradesh, India. J Earth Syst Sci 130:1–11

Shreyasvi C, Venkataramana K (2022) Estimation of Local Site Effects in Indian Scenario: Lessons from Past Earthquakes, Current Practices, and Future Trends. Civ Eng Disaster Risk Reduct 209–226

Sieh K, Natawidjaja D (2000) Neotectonics of the Sumatran fault, Indonesia. J Geophys Res Solid Earth 105:28295–28326

Sunardi B, Daryono D, Arifin J, et al (2012) Kajian Potensi Bahaya Gempabumi Daerah sumbawa Berdasarkan Efek Tapak Lokal. J Meteorol dan Geofis 13:

Syaifuddin F, Bahri AS, Lestari W, Pandu J (2016) Microtremor study of Gunung Anyar mud volcano, Surabaya, East Java. In: AIP Conference Proceedings. AIP Publishing LLC, p 50004

Untang M, Arnold EP, Soetadi R, et al (1985) Southeast Asia Association of Seismology and Earthquake Engineering (SEASEE) Series on Seismology Volume 5: Indonesia. Southeast Asia Association of Seismology and Earthquake Engineering (SEASEE)

Xu R, Wang L (2021) The horizontal-to-vertical spectral ratio and its applications. EURASIP J Adv Signal Process 2021:1–10

Acknowledgements

We thank Physics Lab. of University of Bengkulu for providing microtremor equipment. Data acquisition were carried out by students from Physics department of University of Bengkulu (Ikhlas, Idhili, Hasan and Rama, thanks for fruitful helps). Thanks also to Muhammad Hanif (Department of Geo-Informatics, College of Computing, Khon Kaen University) and Mr. Ravidho Ramadhan (Department of Physics, University of Andalas) for helping with data processing.

Funding

This study was supported by PDU-Riset Publikasi Terindeks (RPT) grant from Universitas Andalas (Contract no: T/113/UN.16.17/PT.01.03/IS-RPT/2022).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

BIS performs data acquisition, processes data, conducts analysis, and writes manuscripts. MM guides the research, secures funding, analyzes research findings, and reviews and proofreads manuscripts. AML: guides the research, analyzes research findings, and reviews and proofreads manuscripts.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Siburian, B.I., Marzuki, M. & Lubis, A.M. Local site effects and seismic microzonation around Suban Area, Curup Rejang Lebong, Bengkulu deduced by ambient noise measurements. Geoenviron Disasters 11, 5 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40677-024-00268-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40677-024-00268-7