Abstract

Background

The Rufous-backed Bunting, Emberiza jankowskii, is an endangered species that is primarily distributed in Inner Mongolia, China. The main threats to the continued persistence of this species are habitat loss and degradation. However, the impact of population loss on genetic diversity remains unclear. To support future conservation and management efforts, we assessed the genetic diversity and population structure of E. jankowskii using mitochondrial DNA and microsatellites.

Methods

Blood samples were collected from 7‒8-day-old nestlings in Inner Mongolia, China between May and August of 2012 and 2013. Mitochondrial DNA sequences and microsatellite markers were used to assess the genetic diversity, genetic structure and inbreeding of E. jankowskii. The results of genetic diversity and inbreeding were compared to other avian species.

Results

We found an unexpectedly high level of genetic diversity in terms of mitochondrial DNA and microsatellite compared to other avian species. However, there were high levels of gene flow and minimal genetic structuring, among the fragmented breeding populations of E. jankowskii in Inner Mongolia. These findings suggest that E. jankowskii in Inner Mongolia is a metapopulation. Despite the high genetic diversity of E. jankowskii, local populations in each small patch remain at risk of extinction due to habitat loss. In addition, the E. jankowskii population has a high risk of inbreeding.

Conclusions

To minimize further loss of genetic diversity of this endangered species, we suggest that the E. jankowskii in Inner Mongolia should be considered as a protected species for management purposes. Conservation efforts should concentrate on E. jankowskii habitat management. This may be most effectively achieved by protecting the current breeding habitats and prohibiting over-grazing.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Genetic diversity is a prerequisite for the adaptation and survival of species (Schonewald-Cox et al. 1983; Lande 1988). Indeed, the level of genetic diversity exhibited by a species reflects its evolutionary potential (Frankel and Soulé 1981). Therefore, evaluations of genetic diversity are essential for species management and the development of conservation strategies, especially for endangered species (Hedrick 2004). Generally, endangered species exist in small populations and exhibit low rates of genetic diversity (Hinkson and Richter 2016). Small populations are more prone to genetic drift, which can randomly reduce genetic variability and population fitness by increasing homozygosity (Lande 1999; Willi et al. 2007; Freeland et al. 2011). Therefore, species with low genetic diversity may lack the ability to adapt to environmental changes, and their potential for long-term survival may be diminished (Liu et al. 2003). However, relatively ancient endangered species (e.g. those that have become endangered over the last 150 years due to habitat fragmentation) may retain high genetic diversity due to long generation times (Lippé et al. 2006).

The Rufous-backed Bunting (Emberiza jankowskii), a small grassland passerine with strict habitat requirements, was a common species throughout its historical breeding range. Historically, E. jankowskii has bred in Heilongjiang, western and eastern Jilin Province in China, extreme northeastern North Korea, and south of the Russian Far East (Wang et al. 2011). Because of habitat fragmentation, human activities, and low reproductive success, populations of this species have declined dramatically over the last 50 years (Jiang et al. 2008). E. jankowskii has been listed as endangered on the IUCN Red List since 2010 (BirdLife International 2018). From 2011–2016, we surveyed the breeding distribution of E. jankowskii in China and demonstrated that this species has vanished from most of its historic breeding sites (Wang et al. 2011; Han et al. 2018). Fortunately, we discovered 13 new E. jankowskii breeding sites in Inner Mongolia. However, these new breeding sites were seriously degraded because of over-grazing, urbanization, and agriculture (Han et al. 2018). During the course of our survey from 2012 to 2018, the populations of E. jankowskii at the new breeding sites began to decline and become increasingly fragmented (Han et al. 2018).

Experimental studies and field investigations have shown that fragmented populations may lose allelic richness and genetic diversity (Buza et al. 2000; Tomimatsu and Ohara 2003). Previously, major histocompatibility complex (MHC class II B) genes were used to examine the genetic diversity of E. jankowskii, and results showed relatively low levels of MHC polymorphisms (Li et al. 2017). MHC genes were mainly relevant to immune function (Mak and Sanderson 1985; Schad et al. 2004). These findings indicate that MHC polymorphisms are affected by selection. The selection pressures on MHC genes can produce discrepancies between patterns of MHC and neutral variation in natural populations (Alcaide et al. 2010; Sutton et al. 2011). MHC polymorphisms will not provide a precise measure of genome-wide diversity. We suggest the use of neutral markers to evaluate the genetic diversity of E. jankowskii.

To investigate the genetic diversity and structure of E. jankowskii based on neutral markers, we (1) used mitochondrial DNA sequences and microsatellite markers to compare this level of genetic diversity to previously published levels of genetic diversity in other avian species, (2) estimated whether E. jankowskii was inbreeding because of low population sizes, (3) determined the genetic structure among populations of E. jankowskii, and (4) discussed the next stage of E. jankowskii conservation work.

Methods

Sample collection

We used a direct search method to find E. jankowskii nests in Gahaitu (GHT), Aolunhua (ALH), Lubei (LB), Chagantaoligao (CG), and Kundu (KD), in Inner Mongolia, China between May and August of 2012 and 2013 (Fig. 1). Blood samples were taken by venipuncture (brachial vein) under the wings of 7–8 day old nestlings. Samples were mixed with absolute ethyl alcohol in 1.5 mL tubes and preserved at − 20 °C.

According to the population density of Han et al. (2018) and the area of our sample sites (GHT 3.87 km2, ALH 4.74 km2, LB 3.91 km2, CG 1.27 km2, and KD 2.55 km2), we assessed the population sizes of five sampling sites. The population size, sampling nests in each sample site, and the distance among sampling sites are presented in Table 1.

Mitochondrial DNA amplification and microsatellite genotyping

Total genomic DNA was isolated using an AxyPrep Blood Genomic DNA Miniprep Kit (Aisijin, Hangzhou, China). All nestlings in the same nest have the same parents, we sampled only one randomly selected nestling per nest (a total of 59 individuals). We used polymerase chain reactions (PCRs) to amplify hypervariable region I (HVI) of the mitochondrial control region using the novel primers A629 (5′-GTATTCAACCGACCACTT-3′) and S19 (5′-CTCCGAGACCTACGACCTG-3′). PCR amplifications were performed in 20 μL volumes containing 10 μL of 2 × Taq PCR Master Mix (Sangon Biotech), 0.25 μL of each primer (10 μM), and 1 μL template DNA. The PCR cycling program was as follows: an initial denaturation step at 94 °C for 5 min; followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 94 °C for 30 s, annealing at 53.7 °C for 30 s, and extension at 72 °C for 30 s; then a final extension at 72 °C for 10 min. All the sequences were deposited in GenBank under accession numbers MH670589–MH670647.

We amplified 10 microsatellite loci from each of the 59 individuals using 10 primer pairs: Ecit3, Dpμ16, Escμ1, Escμ2, Escμ3, Escμ4, LS2, Ecit2, HXW20, and embc30 (Hanotte et al. 1994; Mundy and Woodruff 1996; Dawson et al. 1997; Wonke et al. 2007; Yu et al. 2011; Segelbacher and Schuphan 2014). We optimized the reaction volumes and PCR protocols for each primer pair. Microsatellite loci were scored by Sangon Biotech (Shanghai, China). Final fragment sizes were calculated in GeneMarker v1.91 (SoftGenetics LLC, State College, PA, USA) and scored manually.

Data analysis

Genetic diversity, Hardy–Weinberg, and linkage disequilibrium tests

We calculated various mitochondrial diversity parameters in DnaSP v5.10 (Rozas et al. 2003), including haplotype diversity (Hd), nucleotide diversity (π), and the number of polymorphic and phylogenetically-informative sites (Nei and Tajima 1981; Graur and Li 2000).

We used GENEPOP v4.6 (Rousset 2008) to test for deviations from the Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium and to identify alleles exhibiting linkage disequilibrium among all loci across all populations, using 10,000 dememorizations, 10,000 batches, and 10,000 iterations per batch. Critical significance levels were adjusted for multiple comparisons using the sequential Bonferroni correction (α = p/n; Rice 1989). Loci were checked for the likelihood of null alleles with Micro-checker (Van et al. 2004).

Genetic statistics were used to measure the genetic variability of the microsatellites, observed heterozygosity (Ho) and expected heterozygosity (He) under Hardy–Weinberg were also computed with GENEPOP 4.6. The number of alleles, the number of private alleles, and gene diversity were computed with FSTAT v2.9.3 (Goudet 2001).

Gene flow and inbreeding

We calculated the fixation index (FST) in Arlequin v3.5 and Genetix v4.05 (Nei 1978; Excoffier et al. 1992; Belkhir et al. 1996; Schneider et al. 2000), and gene flow (Nm) was estimated using the equation Nm = 0.25 (1 − FST)/FST (Excoffier et al. 1992; Schneider et al. 2000). The inbreeding coefficient (FIS) was calculated with GENEPOP 4.6.

Population structure

For our phylogenetic analyses, the D-loop sequences of E. schoeniclus (AJ243929), E. cirlus (AJ243928), and Miliaria calandra (AJ243925) were downloaded from GenBank and used as outgroups. The optimal models of nucleotide substitution were determined using the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) in jModelTest v2.1.10 (Posada and Thomas 2004). The best model of nucleotide substitution, as selected by the AIC, was TVM + G. We used maximum likelihood (ML) in PHYML (Guindon et al. 2005), maximum parsimony (MP) and neighbor-joining (NJ) in PAUP* v4.0 (Swofford 2001), and Bayesian inference (BI) in MrBayes v3.1.2 (Huelsenbeck and Ronquist 2001; Ronquist and Huelsenbeck 2003) to construct phylogenies. For the ML analysis, we set the parameters of the custom model based on the AIC results. Networks were constructed by median-joining in Network 5.0 (Bandelt et al. 1999).

We assessed population structure based on a Bayesian analysis of microsatellites. We used STRUCTURE v2.3.3 (Pritchard et al. 2000) to assign individuals to K = 1–5 data clusters, with the higher number of clusters corresponding to the number of populations assessed (Flanders et al. 2009; Mao et al. 2010). We performed 10 replicate STRUCTURE runs for each K value. Monte Carlo Markov chains (MCMCs) were admixed for 2,000,000 cycles using independent models of allele frequencies, with the first 20% of the cycles discarded as ‘burn-in’. The best K value was defined using the ΔK statistic as described by Evanno et al. (2005).

We used the Bayesian method of MIGRATE-N to assess the microsatellite migration rates (Beerli 2006). Five long chains of 1.0 × 106 generations were used for all runs of MIGRATE-N. The same three-step process was conducted on the actual data to form the test statistic. To ensure adequate mixing of Markov chains, we used Markov-coupling, where 4 independent chains were allowed to mix according to an adaptive heating scheme (1.0, 1.2, 1.5, 6.0).

Demographic estimates

To reconstruct the demographic history of E. jankowskii, the historical demographic dynamics of E. jankowskii were inferred from Bayesian skyline analyses implemented in BEAST 2.6.2 (Bouckaert et al. 2019). We used D-loop sequences for this analysis and selected the mean substitution rate at 1.0 to estimate time in units of substitution/site. Independent MCMC analyses were run for 1.0 × 108 steps, sampling every 105 steps, and discarding 1000 samples as burn-in. The results visualized skyline plots with TRACER 1.5 (Drummond and Rambaut 2007). Sequence divergence rate of 2%/Myr was applied to the mtDNA D-loop region (Shields and Wilson 1987).

Results

Genetic diversity

The genetic diversity of E. jankowskii based on mitochondrial DNA and microsatellites is shown in Table 2. Amplification of the control regions (544 bp) from 59 individuals yielded 16 haplotypes with 14 polymorphic sites and 8 parsimony informative sites. The total haplotype diversity (Hd) was 0.874 (standard deviation (SD) = 0.023), and the overall nucleotide diversity (π) was 0.0032 (SD = 0.0003).

We detected no significant departures from the Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium after correcting for the number of pairwise comparisons (n = 49; α = 0.001), with the following exceptions: locus Ecit3 in GHT, LB, and ALH; locus Escμ4 in GHT; locus HXW20 in GHT and CG; and locus embc30 in GHT and ALH. After Bonferroni correction, Fisher’s exact test identified no significantly linked pairs of loci (n = 225, α = 0.0002). The micro-checker analysis did not suggest any scoring errors due to stuttering, nor did it suggest any large allelic dropout in any loci across all populations. Null alleles may have been present in locus Ecit3 in GHT, LB, and ALH; locus Escμ4 in GHT; locus LS2 in LB; locus HXW20 in GHT, ALH, and CG; and locus embc30 in GHT and ALH. Because we identified departures from the Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium and null alleles in the loci Ecit3, HXW20, and embc30 in two or more populations, we deleted these three loci from subsequent analyses.

The number of alleles per locus ranged from 4 to 16 across all populations (mean ± SD: 9.00 ± 5.03), with the most alleles found in the GHT population (7.00 ± 3.87) and the least found in the KD population (3.29 ± 1.11). Private alleles with a frequency over 10% were observed in the KD (PA = 2) and LB (PA = 1) populations. The gene diversity per population was 0.71 ± 0.19 in the GHT population, 0.72 ± 0.14 in the LB population, 0.67 ± 0.15 in the ALH population, 0.75 ± 0.13 in the CG population, and 0.58 ± 0.21 in the KD population. The highest observed heterozygosity (Ho) and expected heterozygosity (He) were observed in the CG population (0.7959 and 0.7551, respectively), while observed heterozygosity was lowest in the ALH population (0.5929) and expected heterozygosity was lowest in the KD population (0.5970) (Table 2).

Average inbreeding coefficient (FIS) of E. jankowskii in Inner Mongolia was estimated as 6.92%. Within population, FIS ranged from − 0.1633 (KD) to 0.1545 (LB) (Table 2).

Based on mitochondrial DNA and microsatellite data, the fixation index (FST) was highest between the CG and LB populations (0.18462) and the CG and KD populations (0.06296), and lowest between the GHT and LB populations (0.00546) and CG and LB populations (0.00411). Thus, gene flow was highest between the GHT and LB populations (45.5376) and CG and LB populations (60.5779), and lowest between the CG and LB populations (1.1041) and CG and KD populations (3.7206) (Tables 3, 4).

Population structure

The NJ, MP, ML, and BI phylogenies were highly congruent. All E. jankowskii haplotypes clustered together, in a clade marked by shallow sequence divergences with no well-supported basal haplotype (Fig. 2). Additional analyses were conducted to assess the genetic structure of five populations by building a median-joining network. The network showed three different second levels (hap 1, 2 and 7), with some significant associations. Based on expectations from the coalescent theory, hap 2 was the haplotype with the highest frequency and most connections, and thus was the most likely ancestral haplotype (Fig. 3).

Phylogenetic tree of E. jankowskii recovered by maximum likelihood analysis. Bootstrap support and posterior probabilities are shown only for nodes highly supported by at least two phylogenetic reconstruction methods (i.e., ≥ 60% maximum likelihood, maximum parsimony or neighbor-joining bootstrap support or ≥ 0.60 Bayesian posterior probability). Outgroups (obtained from GenBank) are indicated by their species names. Colored squares represent different populations. Details of the populations are given in the text

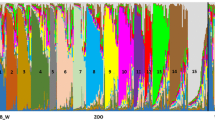

Although the best separation was obtained at K = 2 (ΔK = 1.68), our STRUCTURE simulation indicated that homogenization was occurring across all E. jankowskii populations in Inner Mongolia; clear signs of admixture were observed in all subpopulations (Fig. 4, showing K = 2 and 3 only).

Our analysis of molecular variance (AMOVA), based on the distance matrices among individuals, indicated that the overall variation could be partitioned into two levels (Table 5). The proportion of variation attributable to within-population differences was particularly high (mtDNA: 96.76%; microsatellites: 98.71%). The fixation indices (FST) were 0.03 based on mtDNA, and 0.01 based on microsatellites (P > 0.05). All estimates of genetic differentiation indicated a relatively low level of genetic differentiation across all populations.

The results of Migrate-N show that there were significant gene flows between different populations. There are migrations in and out among the five populations (Table 6).

Demographic history

Due to the existence of gene flow and the absence of genetic structure, we placed E. jankowskii in Inner Mongolia into one group for BSP analysis. The Bayesian skyline plots (BSP) revealed that the population size of E. jankowskii in Inner Mongolia is stable (Fig. 5).

Discussion

High-level genetic diversity and inbreeding

Surveys of genetic diversity in endangered species are essential for the evaluation of the evolutionary and adaptive potential of these species, such surveys are also vital for the development of effective conservation strategies to protect threatened populations, especially those that are fragmented (Zhang et al. 2017; Stevens et al. 2018). In this study, we investigated the genetic diversity of E. jankowskii for the first time, employing mitochondrial DNA sequences and microsatellite data. E. jankowskii had a higher level of haplotype diversity (0.874) and nucleotide diversity (0.0032) in its D-loop gene sequence than other endangered species, such as Nipponia nippon (Hd = 0.386, π = 0.0007) (Zhang et al. 2004) and Megulus palustris sinensis (Hd = 0.772, π = 0.0014) (Zhang 2007). Interestingly, the haplotype and nucleotide diversity of E. jankowskii was also higher than one species of least concern, Parus varius (Hd = 0.5328, π = 0.0017) (Du 2011). The microsatellite results also indicated that E. jankowskii had a higher degree of genetic diversity than all passerines birds (He = 0.24‒0.59), which were listed in the article of Jamieson et al. (2006), and also higher than N. nippon (He = 0.50, Ho = 0.47) (He 2007), and M. palustris sinensis (He = 0.53, Ho = 0.38) (Zhao 2012). The observed heterozygosity of E. jankowskii was higher than Gallus gallus (Ho = 0.37–0.41) and Perdix dauuricae (Ho = 0.58), but the expected heterozygosity of E. jankowskii was a little lower than Gallus gallus (He = 0.72–0.77) and Perdix dauuricae (He = 0.72) (Cao et al. 2010; Masroor et al. 2012).

It is well established that decreases in genetic variation may reduce fitness and adaptability (Allentoft and O’Brien 2010). Generally, endangered species tend to have small population sizes and low levels of genetic diversity due to historical reasons, and reduce fitness (Matocq and Villablanca 2001). Unexpectedly, E. jankowskii exhibited high levels of genetic variability. This indicated that habitat fragmentation and degradation have not led to the rapid loss of genetic diversity in this species. There may be several explanations for this result. First, it is possible that E. jankowskii populations were historically very large (Fu and Chen 1966). Second, the observed reduction in E. jankowskii population sizes occurred during past 50 years (Jiang et al. 2008). This means that due to the small number of generations, E. jankowskii has not experienced a rapid decline in genetic diversity (Welch et al. 2012). Third, birds with higher dispersal abilities may therefore maintain high levels of genetic diversity due to gene flow. Fourth, hybridization and introgression with closely related species can also contribute to the maintenance of high levels of genetic diversity (Mallet 2005). However, whether hybridization and introgression had occurred between E. jankowskii and E. cioides requires further investigation.

Although there are some methods available to minimize inbreeding (Pusey 1987), inbreeding may be inevitable in small, isolated populations and play a role in determining the probability of local extinction events (Frankham 2005). In this study, the average inbreeding coefficient of E. jankowskii in Inner Mongolia was estimated at 0.069 (Table 2), higher than other Passerine birds (FIS = 0.024–0.054) and the captive panda population at the Chengdu (n = 37, FIS = 0.045) (Sun et al. 2010; Abalaka et al. 2015). This indicated that a high inbreeding risk existed for E. jankowskii in Inner Mongolia or may have occurred to some extent. However, high levels of genetic diversity within E. jankowskii populations indicated that inbreeding depression did not occur.

Absence of genetic structure and high levels of gene flow

Genetic population structure imparts important information about species ecology and evolutionary history, including dispersal ability, adaptation, and speciation (Rousset 2004). Genetic population structure can also help to determine important species conservation units in patchy, fragmented habitats (Paetkau 1999). Here, no clear phylogeographic structure was observed across the five E. jankowskii populations in either the phylogenetic tree or the cluster analyses. The FST values of the five populations were relatively low (mtDNA: 0.00546–0.18462; microsatellites: 0.00411–0.06296). In addition, the FST values between populations ALH and LB; KD and LB; ALH and KD; GHT and LB; GHT and CG were negative (Tables 2, 3). Negative values suggest a lack of support for genetic differentiation between these population pairs (Foster et al. 2006).

Gene flow among populations is an important mechanism that maintains intraspecific genetic diversity (Slatkin 1994). Species with low levels of gene flow show more genetic differentiation among populations than do species with high levels of gene flow (Hamrick et al. 1991). In E. jankowskii, various levels of gene flow were calculated among populations (Tables 3, 4). This was consistent with the AMOVA results, which identified more genetic variation within populations than between populations (Table 5). There was an asymmetric gene flow between certain populations (Table 6).

Conservation implications

The five populations of E. jankowskii sampled here exhibited an absence of genetic structure and various levels of gene flow. Thus, E. jankowskii in Inner Mongolia is a metapopulation. We therefore suggest that, for the purposes of species management, E. jankowskii in Inner Mongolia should be defined as one protected unit.

Although E. jankowskii showed high genetic diversity, and E. jankowskii population sizes ranged between 9800 and 12,500 individuals (Han et al. 2018), but the number of individuals in every single patch is small (Table 1) and with high inbreeding risk. The local population in each patch might vanish due to habitat loss (Wang et al. 2011). Therefore, conservation policies limiting habitat destruction are necessary to mitigate the threat of species extinction.

The E. jankowskii in Inner Mongolia is still at risk of human disturbances, habitat loss, and habitat degradation (Han et al. 2018). The extremely limited habitat of this species (similar to the habitat requirements of Prunus sibirica and Stipa baicalensis on the Mongolian steppes) might make E. jankowskii very sensitive to habitat fragmentation, water pollution, global warming, and the degradation of habitats suitable for P. sibirica and S. baicalensis. Thus, habitat conservation and population management are urgently needed for this avian species. Indeed, the high genetic variability of E. jankowskii indicates the ability to recover if provided with effective protection (Evans and Sheldon 2008). Therefore, we suggest that management efforts for this species focus on the protection of the current breeding habitats and elimination of over-grazing. Establishing specific natural areas to preserve the breeding habitats of E. jankowskii and publicizing the importance of protecting this avian species to local residents might also be effective and should be considered. We hope that our work contributes to the establishment of a management and protection system for E. jankowskii. Our laboratory will continue to carry out the long-term monitoring of this species.

Future prospects

This study has shown that E. jankowskii exhibits a high level of genetic diversity. We found that E. cioides, a closely related species (Alström et al. 2008), had overlapping distributions with E. jankowskii in Inner Mongolia. Several studies have indicated that species in nature are often incompletely isolated for millions of years after speciation. There are many cases of hybridization and introgression occurred among closely related sympatric species (Mallet 2005). Whether hybridization and introgression had occurred between E. jankowskii and E. cioides and whether this contributes to the high level of genetic diversity of E. jankowskii require further investigation.

Conclusions

E. jankowskii in Inner Mongolia is a metapopulation, so we suggest that the E. jankowskii in Inner Mongolia should be considered one protected unit for management purposes. The conservation efforts should concentrate on protecting the current breeding habitats and forbidding over-grazing.

Availability of data and materials

The data on which this paper was made are fully available at the appendix of the manuscript.

References

Abalaka J, Hudin NS, Ottosson U, Bloomer P, Hansson B. Genetic diversity and population structure of the range restricted rock firefinch Lagonosticta sanguinodorsalis. Conserv Genet. 2015;16:411–8.

Alcaide M, Lemus JA, Blanco G, Tella JL, Serrano D, Negro JJ, et al. MHC diversity and differential exposure to pathogens in kestrels (Aves: Falconidae). Mol Ecol. 2010;19:691–705.

Allentoft M, O’Brien J. Global amphibian declines, loss of genetic diversity and fitness: a review. Diversity. 2010;2:47–71.

Alström P, Olsson U, Lei F, Wang HT, Sundberg P. Phylogeny and classification of the Old World Emberizini (Aves, Passeriformes). Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2008;47:960–73.

Bandelt HJ, Forster P, Röhl A. Median-joining networks for inferring intraspecific phylogenies. Mol Biol Evol. 1999;16:37–48.

Beerli P. Comparison of Bayesian and maximum likelihood inference of population genetic parameters. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:341–5.

Belkhir K, Borsa P, Chikhi L, Raufaste L, Bonhomme F. GENETIX 4.05, logiciel sous Windows TM pour la génétiquedes populations. Laboratoire génome, populations, interactions, CNRS UMR. 5000. 1996–2004. http://www.genetix.univ-montp2.fr/genetix/genetix.htm.

BirdLife International. Emberiza jankowskii. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2018: e.T22720905A132004685. 2018. https://doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2018-2.RLTS.T22720905A132004685.en.

Bouckaert R, Timothy GV, Joëlle BS, Sebastián D, Mathieu F, Alexandra G, et al. BEAST 2.5: an advanced software platform for Bayesian evolutionary analysis. PLoS Comput Biol. 2019;15:e1006650.

Buza L, Young A, Thrall P. Genetic erosion, inbreeding and reduced fitness in fragmented populations of the endangered tetraploid pea Swainsona recta. Biol Conserv. 2000;93:177–86.

Cao M, Liu N, Wang X, Guan M. Genetic diversity and genetic structure of the Daurian Partridge (Perdix dauuricae) in China, assessed by microsatellite variation. Chin Birds. 2010;1:51–64.

Dawson RJ, Gibbs HL, Hobson KA, Yezerinac SM. Isolation of microsatellite DNA markers from a passerine bird, Dendroica petechia (the yellow warbler), and their use in population studies. Heredity. 1997;79:506–14.

Drummond AJ, Rambaut A. BEAST: Bayesian evolutionary analysis by sampling trees. BMC Evol Biol. 2007;7:214.

Du Y. Genetic diversity of Varied Tit (Parus varius) inferred with mitochondrial DNA control region and nuclear microsatellite markers. Master’s Thesis. Shenyang, China: Liaoning University; 2011.

Evanno G, Regnaut S, Goudet J. Detecting the number of clusters of individuals using the software structure: a simulation study. Mol Ecol. 2005;14:2611–20.

Evans SR, Sheldon BC. Interspecific patterns of genetic diversity in birds: correlations with extinction risk. Conserv Biol. 2008;22:1016–25.

Excoffier L, Smouse PE, Quattro JM. Analysis of molecular variance inferred from metric distances among DNA haplotypes: application to human mitochondrial DNA restriction data. Genetics. 1992;131:479–91.

Flanders J, Jones G, Benda P, Dietz C, Zhang S, Li G, et al. Phylogeography of the greater horseshoe bat, Rhinolophus ferrumequinum: contrasting results from mitochondrial and microsatellite data. Mol Ecol. 2009;18:306–18.

Foster CB, Aswath K, Chanock SJ, Mckay HF, Peters U. Polymorphism analysis of six selenoprotein genes: support for a selective sweep at the glutathione peroxidase 1 locus (3p21) in Asian populations. BMC Genet. 2006;7:56.

Frankel OH, Soulé ME. Conservation and evolution. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1981.

Frankham R. Genetics and extinction. Biol Conserv. 2005;126:131–40.

Freeland JR, Kirk H, Petersen S. Molecular ecology. 2nd ed. Chichester: Wiley; 2011.

Fu TS, Chen P. The distribution and breeding habitats of Emberiza jankowskii. Acta Zool Sin. 1966;18:197–8.

Goudet J. FSTAT, version 2.9.3, a program to estimate and test gene diversities and fixation indices. Lausanne: Lausanne University; 2001.

Graur D, Li WH. Fundamentals of molecular evolution. 2nd ed. Sunderland: Sinauer Associates; 2000.

Guindon S, Lethiec F, Duroux P, Gascuel O. Phyml online—a web server for fast maximum likelihood-based phylogenetic inference. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:W557–9.

Hamrick JL, Godt MJW, Murawshi DA, Loveless MD. Correlations between species traits and allozyme diversity: implications for conservation biology. In: Falk DA, Holsinger KE, editors. Genetics and conservation of rare plants. New York: Oxford University Press; 1991. p. 75–86.

Han Z, Zhang L, Qin B, Wang L, Liu Y, Fu V, et al. Updated breeding distribution and population status of Jankowski’s Bunting Emberiza jankowskii in China. Bird Conserv Int. 2018;28:643–52.

Hanotte O, Zanon C, Pugh A, Greig C, Dixon A, Burke T. Isolation and characterization of microsatellite loci in a passerine bird: the reed bunting Emberiza schoeniclus. Mol Ecol. 1994;3:529–30.

He LP. Isolation of polymorphic microsatellite loci and analysis of genetic diversity in Crested Ibis (Nipponia nippon). Ph.D Thesis. Hangzhou: Zhejiang University; 2007.

Hedrick PW. Recent developments in conservation genetics. Forest Ecol Manag. 2004;197:3–19.

Hinkson KM, Richter SC. Temporal trends in genetic data and effective population size support efficacy of management practices in critically endangered dusky gopher frogs (Lithobates sevosus). Ecol Evol. 2016;6:2667–78.

Huelsenbeck JP, Ronquist F. Mrbayes: Bayesian inference of phylogenetic trees. Bioinformatics. 2001;17:754–5.

Jamieson IG, Wallis GP, Briskie JV. Inbreeding and endangered species management: is New Zealand out of step with the rest of the world? Conserv Biol. 2006;20:38–47.

Jiang YL, Gao W, Lei FM, Wang HT, Wan DM, Zhao J. Nesting biology and population dynamics of Jankowski’s Bunting Emberiza jankowskii in Western Jilin, China. Bird Conserv Int. 2008;18:153–63.

Lande R. Genetics and demography in biological conservation. Science. 1988;241:1455–60.

Lande R. Extinction risks from anthropogenic, ecological, and genetic factors. In: Landweber LF, Dobson AP, editors. Genetics and the extinction of species: DNA and the conservation of biodiversity. Princeton: Princeton University Press; 1999. p. 1–22.

Li D, Sun K, Zhao Y, Lin A, Li S, Jiang Y, et al. Polymorphism in the major histocompatibility complex (MHC class II B) genes of the Rufous-backed Bunting (Emberiza jankowskii). PeerJ. 2017;5:e2917.

Lippé C, Dumont P, Bernatchez L. High genetic diversity and no inbreeding in the endangered copper redhorse, Moxostoma hubbsi (Catostomidae, Pisces): the positive sides of a long generation time. Mol Ecol. 2006;15:1769–80.

Liu D, Shen H, Yang Y, Zhang J. Genetic diversity of rare and endangered plant Sorbus amabilis. J Appl Ecol. 2003;14:2141–4.

Mak NK, Sanderson CJ. The T-cell mediated immune response to Schistosoma mansoni. I. Generation of stage-specific, MHC-restricted proliferative T-cell clones to soluble egg antigens. Immunology. 1985;54:625–33.

Mallet J. Hybridization as an invasion of the genome. Trends Ecol Evol. 2005;20:229–37.

Mao XG, Zhu GJ, Zhang S, Rossiter SJ. Pleistocene climatic cycling drives intra-specific diversification in the intermediate horseshoe bat (Rhinolophus affinis) in Southern China. Mol Ecol. 2010;19:2754–69.

Masroor EB, Asif N, Tanveer H, Wajid A, Shah SA, Iqbal A. Microsatellite marker based genetic diversity among four varieties of Pakistani Aseel chicken. Pak Vet J. 2012;32:237–41.

Matocq MD, Villablanca FX. Low genetic diversity in an endangered species: recent or historic pattern? Biol Conserv. 2001;98:61–8.

Mundy NI, Woodruff DS. Polymorphic microsatellite markers in the loggerhead shrike Lanius ludovicianus isolated from a library enriched for CA repeats. Mol Ecol. 1996;5:811–3.

Nei M. Estimation of average heterozygosity and genetic distance from a small number of individuals. Genetics. 1978;89:583–90.

Nei M, Tajima F. DNA polymorphism detectable by restriction endonucleases. Genetics. 1981;97:145–63.

Paetkau D. Using genetics to identify intraspecific conservation units: a critique of current methods. Conserv Biol. 1999;13:1507–9.

Posada D, Thomas B. Model selection and model averaging in phylogenetics: advantages of Akaike information criterion and Bayesian approaches over likelihood ratio tests. Syst Biol. 2004;53:793–808.

Pritchard JK, Stephens M, Donnelly P. Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data. Genetics. 2000;155:945–59.

Pusey AE. Sex biased dispersal and inbreeding avoidance in birds and mammals. Trends Ecol Evol. 1987;2:295–9.

Rice WR. Analyzing tables of statistical tests. Evolution. 1989;43:223–5.

Ronquist F, Huelsenbeck JP. Mrbayes 3: Bayesian phylogenetic inference under mixed models. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:1572–4.

Rousset F. Genetic structure and selection in subdivided populations (MPB-40). Princeton: Princeton University Press; 2004.

Rousset F. GENEPOP’007: a complete re-implementation of the GENEPOP software for Windows and Linux. Mol Ecol Resour. 2008;8:103–6.

Rozas J, Sánchez-DelBarrio JC, Messeguer X, Rozas R. DnaSP, DNA polymorphism analyses by the coalescent and other methods. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:2496–7.

Schad J, Sommer S, Ganzhorn JU. MHC variability of a small lemur in the littoral forest fragments of southeastern Madagascar. Conserv Genet. 2004;5:299–309.

Schneider S, Kueffer JM, Roessli D, Excoffier L. Arlequin ver 1.1: a software package for population genetics. Genetics and Biometry Laboratory, University of Geneva, Switzerland. 2000. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/239792877.

Schonewald-Cox CM, Chambers SM, MacBryde B, Thomas WL. Genetics and conservation: a reference for managing wild animals and plant populations. Menlo Park: Benjamin/Cummings Publishings; 1983.

Segelbacher G, Schuphan I. Isolation of 13 tetranucleotide microsatellite loci in the Rock Bunting (Emberiza cia). Conserv Genet Resour. 2014;6:597–9.

Shields GF, Wilson AC. Calibration of mitochondrial DNA evolution in geese. J Mol Evol. 1987;24:212–7.

Slatkin M. Gene flow and population structure. In: Real LA, editor. Ecological genetics. Princeton: Princeton University Press; 1994. p. 3–17.

Stevens K, Harrisson KA, Hogan FE, Cooke R, Clarke RH. Reduced gene flow in a vulnerable species reflects two centuries of habitat loss and fragmentation. Ecosphere. 2018;9:e02114.

Sun XY, Zhang ZH, Zhang WP, Shen FZ, Wang YZ. State of gene flow between captive giant pandas populations. Sichuan J Zool. 2010;29:333–9.

Sutton JT, Nakagawa S, Robertson BC, Jamieson IG. Disentangling the roles of natural selection and genetic drift in shaping variation at MHC immunity genes. Mol Ecol. 2011;20:4408–20.

Swofford DL. Paup: Phylogenetic analysis using parsimony (and other methods), 4.0b. Sunderland: Sinauer Associates; 2001.

Tomimatsu H, Ohara M. Genetic diversity and local population structure of fragmented populations of Trillium camschatcense (Trilliaceae). Biol Conserv. 2003;109:249–58.

Van OC, Hutchinson WF, Wills DP, Shipley P. Micro-Checker: software for identifying and correcting genotyping errors in microsatellite data. Mol Ecol Notes. 2004;4:535–8.

Wang H, Jiang Y, Gao W. Jankowski’s Bunting (Emberiza jankowskii): current status and conservation. Chin Birds. 2011;1:251–8.

Welch AJ, Wiley AE, James HF, Ostrom PH, Stafford TW, Fleischer RC. Ancient DNA reveals genetic stability despite demographic decline: 3,000 years of population history in the endemic Hawaiian Petrel. Mol Biol Evol. 2012;29:3729–40.

Willi Y, Van BJ, Schmid B, Fischer M. Genetic isolation of fragmented populations is exacerbated by drift and selection. J Evol Biol. 2007;20:534–42.

Wonke G, Wallschläger D, Moll K, Tiedemann R. Ten new microsatellite loci for the yellowhammer (Emberiza citrinella) and their cross-species applicability among related taxa. Mol Ecol Resour. 2007;7:1278–80.

Yu D, Peng J, Gao S, Fu M, Wang L, Hu S, et al. Development of 15 dinucleotide microsatellite markers from the enriched library of yellow-breasted bunting (Emberiza aureola). Conserv Genet Resour. 2011;3:693–5.

Zhang WW. Genetic diversity and classification research of Japanese Marsh Warbler (Megulus palustris sinensis). Master’s Thesis. Harbin: Northeast Forestry University; 2007.

Zhang B, Fang SG, Xi YM. Low genetic diversity in the endangered Crested Ibis Nipponia nippon and implications for conservation. Bird Conserv Int. 2004;14:183–90.

Zhang Y, Liu B, Dong L, Jiang H, Wang X, Wang X, et al. High genetic diversity and absence of phylogeographic structure in breeding populations of vulnerable Saundersilarus saundersi (Charadriiformes: Laridae) in Bohai Bay. China. Conserv Genet. 2017;18:495–500.

Zhao XQ. Population structure of Japanese Marsh Warbler (Megalurus pryeri) by microsatellite. Master’s Thesis. Harbin: Northeast Forestry University; 2012.

Acknowledgements

We thank Bo Zhang and Huijuan Tao for field support. We thank LetPub (www.letpub.com) for its linguistic assistance during the preparation of this manuscript.

Funding

This work was financed by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 31601856 and 31670398).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SL and DL made equivalent contributions to this paper: both conceived and designed the experiments, carried out the molecular genetic analysis, participated in the manuscript’s design, and drafted the manuscript. YJ developed the ideas and obtained funding support. LZ and BQ helped collect samples and classify species. WS helped perform the microsatellite experiments. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study conformed to the guidelines for the care and use of experimental animals established by the Ministry of Science and Technology of the People’s Republic of China (Approval number: 2006–398). The research protocol was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of Jilin Agriculture University.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, S., Li, D., Zhang, L. et al. High levels of genetic diversity and an absence of genetic structure among breeding populations of the endangered Rufous-backed Bunting in Inner Mongolia, China: implications for conservation. Avian Res 12, 7 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40657-020-00236-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40657-020-00236-3