Abstract

Electrical conductivity in minerals is sensitive to hydrogen content, and therefore, it is a potentially important property from which one can infer hydrogen (water) distribution in the mantle. However, there has been much confusion in the reported results on hydrogen-assisted conductivity. In this paper, I review the existing experimental observations on hydrogen-enhanced electrical conductivity in olivine and other minerals to identify the causes of confusion. Hydrogen loss as well as hydrogen gain could occur during a conductivity measurement at high pressures and temperatures. Particularly important is the unrecognized hydrogen gain during an experiment that could lead to a large degree of error. Many experiments were conducted under the conditions where specimens were super-saturated with hydrogen making the validity of those results unclear. A model for hydrogen loss is developed showing a strategy by which hydrogen loss can be minimized.

When one selects the experimental results in which the influence of hydrogen loss/gain are carefully examined, there is no major discrepancy among the results from different laboratories except differences between the results from low and high temperatures. Differences between low-temperature and high-temperature results are caused by the change in conduction mechanism. At low temperatures, conduction is due to the migration of interstitial (“free”) proton and is nearly isotropic, whereas conduction at high temperatures is due to the migration of two protons at M-site that is highly anisotropic. There is no evidence for substantial concentration dependence of activation enthalpy. Observed exceptionally large concentration dependence reported by Poe et al. (Phys Earth Planet Inter 181:103-111, 2010) is inconsistent with all other reports and is likely caused by some experimental artifact.

Experimental results in the high-temperature regime explain a majority of geophysical observations on the conductivity of the oceanic asthenosphere: partial melting is not needed in most regions and is rather inconsistent with the observations on the matured oceanic mantle. Exception is the asthenosphere near the ridge and/or near the trench where very high conductivity (~ 0.1 S/m) is reported at the top of the asthenosphere. Partial melting might play some role in these regions.

Electrical conductivity in the continental lithosphere cannot be attributed entirely to olivine. An important role of orthopyroxene and/or other minor materials (graphite, sulfide) is needed to explain high conductivity reported in some regions such as Bushveld in South Africa.

The largest remaining uncertainty is the degree to which hydrogen affects electrical conductivity in the lower mantle minerals. Determining the influence of hydrogen on electrical conductivity in lower mantle minerals is critical to make progress in understanding the global water circulation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hydrogen (water) affects melting relationships and rheological properties both of which play a major role in controlling the evolution and dynamics of Earth. Consequently, inferring the hydrogen distribution in Earth is important in our understanding of evolution and dynamics of Earth and other planetary interiors. In most geophysical studies on the composition of Earth’s interior, the focus are seismological observations such as seismic wave velocities, but the seismic wave velocity is rather insensitive to water content but sensitive to other parameters such as the major element chemistry as shown by (Karato 1995, 2011). Consequently, one cannot obtain robust constraints on water content from seismological observations alone (e.g., Houser 2016; Meier et al. 2009; Wang et al. 2019). In contrast, electrical conductivity is sensitive to water (hydrogen) content as suggested by Karato (1990). This idea has been tested, and it has been shown that indeed electrical conductivity is highly sensitive to hydrogen content and insensitive to other factors such as the major element chemistry (Karato 2011). Consequently, electrical conductivity should be a very good property from which one can infer the water (hydrogen) distribution in Earth and other terrestrial planets.

To benchmark this approach, Dai and Karato (2009a) used the experimental data collected in the Karato’s lab on electrical conductivity of olivine and orthopyroxene to conclude that the high conductivity of the asthenosphere on the order of ~ 10− 2 S/m can be explained by geochemically plausible water content of ~ 0.01 wt% (e.g., Hirschmann 2006). This demonstrates the usefulness of electrical conductivity to infer the water distribution. Karato (2011) further extended this approach to the deep upper mantle and transition zone at the global scale and showed that the geophysically inferred electrical conductivity of the transition zone can be explained by a water content of ~ 0.1 wt% with large regional variations. Such a conclusion is consistent with the observation of a water-rich ringwoodite in a diamond inclusion (Pearson et al. 2014) indicating that some region in the transition zone is water-rich. Similarly, (Schmandt et al. 2014) reported seismological observations in the shallow lower mantle suggesting that water-rich transition zone materials transported to the lower mantle promote melting.

However, there have been numerous publications in which rather different conclusions were derived from the laboratory studies on hydrogen-assisted conductivity. For example, Yoshino and his group published papers where they claimed “Hydrous olivine unable to account for conductivity anomaly at the top of the asthenosphere explain” (Yoshino et al. 2006) and “Dry mantle transition zone inferred from the conductivity of wadsleyite and ringwoodite” (Yoshino et al. 2008).

Similarly, Naif et al. (2013) discussed that hydrogen model would requires too much hydrogen (water) to explain the observed conductivity in the shallow asthenosphere and concluded that partial melt is needed, a conclusion similar to that of Yoshino et al. (2006). Naif et al. (2013)’s discussion as well as Yoshino’s are based on the extrapolation of low temperature results that is not justifiable as shown by Dai and Karato (2014b) and Karato (2013) (I will discuss this issue in a later part of this paper). Naif et al. (2013) concluded that a few % of melt can explain the observed conductivity and supported a partial melt model. As was discussed in detail by Karato (2012, 2014), it is difficult to have that much of melt in most of the Earth’s interior, and consequently, if a partial melt model requires a few % of melt, then this model is also not viable in explaining the observed high conductivity.

Having seen a vast range of published results or interpretations, one may take two different approaches to deal with them. One is to accept the validity of (nearly) all published results and try to come up with an equation that is compatible with all or most of the published results. This approach was taken by Gardés et al. (2014) and Jones (2014) where they claim that concentration-dependent activation enthalpy model adopted by Yoshino et al. (2008) and used by Poe et al. (2010) would explain most of the published results.

However, when one investigates such a delicate property as hydrogen-assisted conductivity, accepting (almost) all the published results may not be a valid approach. As I have discussed in the past Karato (2011) and Karato and Wang (2013), all key steps must be followed carefully to obtain reliable results on hydrogen-assisted conductivity, but some previous studies did not follow some of these steps. In these cases, using these results without corrections will obscure our understanding of the nature of hydrogen-enhanced conductivity.

In contrast to the approach taken by Gardés et al. (2014) and Jones (2014), I will attempt to identify the physical reasons for vastly different experimental results and will develop a unified model based on the selected data. I will show that there are three key points in analyzing the results of hydrogen-enhanced electrical conductivity to which one needs to pay great attention: (i) there are subtleties in the control and characterization of hydrogen in a sample and the failure to deal with this could lead to large errors in the results. (ii) Hydrogen in olivine and other minerals is dissolved as multiple species with different concentration and mobility leading to a complex behavior in electrical conductivity and diffusion. (iii) The concentration-dependent activation enthalpy model that has been proposed by Yoshino et al. (2008) and used by Gardés et al. (2014) and Jones (2014) has never been demonstrated for hydrogen-assisted electrical conductivity in any minerals, and rather there is a physical reason why it should not apply to a case of hydrogen-assisted conductivity.

If a correct method of conductivity measurement (i.e., the impedance spectroscopy) is used, if a proper care is taken to deal with the possible hydrogen loss or gain during an experiment, and if the complexities caused by the presence of multiple hydrogen-related species are included in the interpretation of the data, a majority of the discrepancies among different studies can be explained by a unified model involving two distinct mechanisms of conduction. I conclude that hydrogen-assisted conductivity is the best model to explain the geophysical observations of electrical conductivity in the majority of the upper mantle and that there is no need for partial melting to explain geophysical observations on electrical conductivity except for some limited regions.

Some issues in the experimental studies of electrical conductivity

The impedance spectroscopy versus one-frequency measurements

Measurements of electrical conductivity of materials are tricky when conduction is due to the migration of ions (ionic conductivity). When ionic conductivity dominates, ions migrate due to the applied electric field towards the electrodes. At the electrode, ions must exchange electrons with the electrode. This takes finite time, and hence, some electric charge is built up at the electrode. This charge will retard further migration of ions and gives apparently low electrical conductivity. Consequently, a DC (or one low frequency) measurement of electrical conductivity gives erroneous results when conduction is due to the migration of ions.

In order to avoid this problem, impedance spectroscopy is usually used. In this approach, one applies AC voltage with a range of frequencies and uses a model where a pair of electrodes is modeled as a capacitor. After taking the impedance response of a specimen for a broad range of frequencies, one can calculate the DC conductivity. This method has been used by most of researchers (e.g., Huang et al. 2005; Xu et al. 1998), but in early studies, Yoshino and his co-workers used one low frequency (0.01 or 0.1 Hz) in their studies (Manthilake et al. 2009; Yoshino et al. 2008, 2006).

The use of this inappropriate method leads to two important misconceptions: (i) in most cases, this method gives systematically higher resistivity than true resistivity (see Fig. 1a). The degree to which this happens is larger at higher temperatures where more charge accumulation occurs at electrodes. Also the degree to which this artifact occurs is larger for a sample with higher water content. Consequently, this leads to an apparent concentration dependence of activation enthalpy (Fig. 1b; see section Parameterization of electrical conductivity). (ii) When such results are extrapolated to higher temperatures, there is systematic under-estimation of conductivity. The “discrepancy” between Karato group’s results and Yoshino’s results is largely due to the use of this incorrect method in Yoshino’s group as shown by Karato and Dai (2009). Yoshino later started to use impedance spectroscopy, and obtained results that are not far from our results (e.g., Yoshino et al. 2012) although that paper contains another problem for “dry” samples as will be discussed in the next section.

Results showing the importance of using the impedance spectroscopy (from by Karato and Dai (2009), for wadsleyite). a Typical results of the impedance spectroscopy. The correct measurements should include a wide frequency range showing a half circle, and the intercept of the half circle (shown by R (correct)) of the Z′ axis provides the estimate of resistivity (from Karato and Dai (2009)). In this figure, we show the results using one frequency (0.01 Hz) as Yoshino (Yoshino et al. 2008, 2006) did. These two methods lead systematic difference in the estimated resistivity. b A comparison of the results from the impedance spectroscopy and from one-frequency (0.01 Hz) measurements (incorrect method) and from the inversion of the impedance spectroscopy. Incorrect one-frequency method leads to the results similar to (Manthilake et al. 2009; Yoshino et al. 2008) (shown by YMMK), but these results show systematic difference from the results from the correct method. Activation enthalpy determined by the incorrect method is systematically lower than the true activation enthalpy. For dry samples where conductivity is due to electron holes, very little difference is seen (a small difference is due to the fact that Yoshino’s “dry” samples are not truly dry). The difference is larger for samples with larger water content. This leads to the apparent water content dependence of activation enthalpy

Hydrogen loss/gain

Measurements of electrical conductivity of minerals containing hydrogen are challenging for several reasons. Firstly, measurements of any defect-related properties (electrical conductivity, high-temperature creep) are complex because these properties are sensitive to many physical and chemical parameters such as temperature, pressure, oxygen fugacity, and hydrogen fugacity. Secondly, however, in almost all laboratory studies, a sample is not in chemical equilibrium during electrical conductivity measurement.

And more importantly, the behavior of hydrogen is delicate because it can be lost from a sample or a sample may gain hydrogen during an experiment. I will show some examples of hydrogen loss and gain during electrical conductivity measurements in sections Hydrogen loss and Hydrogen gain in a nominally "dry" experiment.

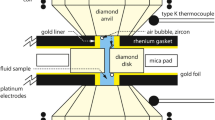

Another difficulty that is unique to electrical conductivity measurements of hydrogen-bearing mineral is that it is hard to conduct experiments where a sample is under well-defined thermochemical conditions. In an ideal experiment, a sample must contain the hydrogen-related defect whose concentration corresponds to the thermochemical conditions under which conductivity is measured. In order to achieve those conditions, a sample must exchange key elements such as hydrogen with the surroundings (the open system behavior). It is possible to realize such a sample assembly at high pressures using hydrogen fugacity buffer such as developed by Otsuka and Karato (2011), but the use of such a buffer in electrical conductivity measurements is difficult because the buffer materials have low electrical resistance.

An alternative way to keep hydrogen in a sample is to seal a sample using some metal jacket or a capsule. A commonly used metal for this purpose is Au-Pd (e.g., Kawamoto and Hirose 1994), but the use of a metal jacket in the conductivity measurement is difficult and I do not know any successful examples (Yang (2012) used a BN capsule to keep hydrogen in the sample assembly with some success).

Considering these difficulties, a common practice is to conduct an experiment in which the composition of a sample is nearly fixed (nearly closed system). In these experiments, the concentration of defects such as the total hydrogen content is fixed, and the fixed value is determined at the conditions where a sample was prepared (high T, P annealing with a given chemical condition). When one changes temperature during an experiment, defect mobility changes and the relative population of various defects may also change (e.g., Karato 2013, 2015a) but not the total number of hydrogen.

When one applies these laboratory results to estimate water content in Earth, one also assumes that Earth also behaves like a closed system. I consider that this is a valid approach, because diffusion time scale for a region larger than ~ 10 km exceeds the age of Earth, and therefore, large regions can be considered as a closed system: chemical composition of these large regions can change only through large-scale melt segregation upon partial melting. After partial melting, the chemical composition of the region is essentially fixed.

However, the assumption of the closed system behavior is not valid when one considers the exchange of hydrogen among co-existing minerals. In such a case, the space scale is several millimeter to centimeter, and chemical equilibrium is likely established. Therefore, the influence of hydrogen partitioning among co-existing minerals is important in assessing the water content in various regions (e.g., Dai and Karato 2009a, see also section Conductivity of the lithosphere).

Hydrogen loss

Hydrogen loss during a conductivity measurement is an obvious possibility, and in the first study of electrical conductivity of hydrogen-bearing minerals, Huang et al. (2005) recognized that hydrogen loss occurred in some of their samples (in some runs, a large fraction of hydrogen was lost. In these cases, the results were rejected). Similarly, Yoshino et al. (2006) reported the evidence of hydrogen loss during their measurements of electrical conductivity in single crystal olivine.

When a sample containing hydrogen is placed in the environment with low hydrogen fugacity, hydrogen tends to escape from a sample to the surroundings via diffusion. The hydrogen loss also occurs due to the migration of protons (by the electric field) in a sample to the electrode where protons are accumulated and lost.

The degree of hydrogen loss is high at high temperatures where hydrogen mobility is high. Yoshino and Katsura argue that hydrogen always escapes from the sample above ~ 1000 K, and therefore, results above this temperature are unreliable. Indeed, their conductivity measurements are always below ~ 1000 K (e.g., Yoshino 2010; Yoshino and Katsura 2013). These authors consider that low temperature results are reliable and extrapolate these data to asthenosphere (~ 1600 K) and argue that hydrogen cannot explain high conductivity in the asthenosphere (see also Naif et al. 2013).

Let us consider how hydrogen loss might occur. Hydrogen loss could occur either by diffusion or by the migration of hydrogen caused by the electric field. Diffusion loss time scale can be calculated from the effective diffusion coefficient for hydrogen loss from \( \tau \approx \frac{{\left(d/2\right)}^2}{\pi^2D} \). Using the lab data (e.g., Kohlstedt and Mackwell 1998), I get τ≈ 1 h at 1400 K. A typical time duration for a conductivity measurement at one temperature is ~ 10 min. Therefore, for a typical conductivity measurement, diffusion loss is not important (although diffusion loss near the electrode could affect the conductivity measurement).

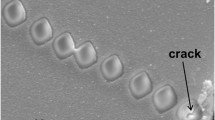

Another important mechanism of hydrogen loss is the hydrogen loss at the electrode. When protons reach to an electrode, unlike electrons (or electron holes), protons cannot go into the electrode, and therefore, they will be accumulated near the electrode (this gives capacitance behavior seen in the Z′ − Z″ plot). When the concentration of protons goes beyond the solubility limit, they will diffuse out of the sample.

If high-frequency field is used, then the mean distance of migration of protons is shorter, and hence, a majority of protons will be preserved. In contrast, when a low-frequency field is applied, a large fraction of protons will reach the electrode and will be lost.

The degree to which this occurs can be estimated roughly by the mean distance by which a proton migrates driven by the applied electric field. Therefore, we can use the following non-dimensional parameter to evaluate the degree of hydrogen loss, viz.,

where l is the mean distance of migration of proton, d is the sample thickness, μ is the mobility of proton, E is the electric field, and ω is the frequency. If ξ > 1, a substantial hydrogen could occur (assuming the fast reaction at the electrode), whereas if ξ ≪ 1, hydrogen loss is small.

Figure 2 shows a plot of ξ as a function of (the lowest) frequency (ω) using the following values, q = 1.9 × 10− 19 C, d = 0.5 mm, and E = 2000 V/m (1 V across 0.5 mm). Since σ ∝ CH approximately, the results do not depend strongly on the hydrogen content. Since conductivity increases with temperature, tendency for hydrogen loss is large at high temperatures. For this voltage (1 V) and the lowest frequency of 0.01 Hz (typical parameters in an experiment), substantial hydrogen loss occurs (ξ > 1) above ~ 1000 K. This is consistent with some experimental observations (e.g., Yoshino et al. 2006). In contrast, if the lowest frequency is 1 kHz, hydrogen loss is much smaller. Also, if one uses a smaller voltage, the degree of hydrogen loss is smaller (for 0.1 V, the critical temperature for hydrogen loss increases by ~ 300 K compared to 1 V).

A figure showing the conditions where hydrogen loss caused by the migration of hydrogen (protons) to the electrode. The degree of hydrogen loss can be characterized by a non-dimensional parameter, \( \xi\;\left(\equiv \frac{l}{d}\propto \frac{E}{\omega}\right) \) (l is the mean distance of hydrogen migration by the electrical field, d is the thickness of the specimen). If ξ ≥ 1, substantial hydrogen loss will occur, whereas if ξ ≪ 1, hydrogen loss is not important. This factor is highly sensitive to the (lowest) frequency and the voltage used. Using high frequencies and/or low voltage, the hydrogen loss can be minimized

Although the above analysis suggests that one can minimize the hydrogen loss using high frequencies and/or low voltage, it is important to confirm that a substantial hydrogen loss (or gain) did not occur during a conductivity measurement. To do this, one must measure the hydrogen content both before and after a measurement. It is also very useful to test if a substantial hysteresis is present during a measurement. If hydrogen loss (or gain) occurs during the conductivity measurement, there should be hysteresis, i.e., discrepancy in the results during a temperature cycling. In all our studies, these steps were followed, and when a substantial change in water content occurred, we rejected the data. But Poe et al. (2010) did not check the water loss or gain during their experiments. They only measured the water content after the experiments. As will be discussed later, their results are anomalous (the dependence of conductivity on water content including the water content dependence of activation energy is much stronger than those reported in all other publications) and I suspect that changes in water content or state of water during their experiments might be the cause for these anomalous results.

Hydrogen gain in a nominally “dry” experiment

The possibility of hydrogen loss during an experiment is well recognized, but the evidence of hydrogen gain was also recognized after the first successful study of hydrogen-enhanced electrical conductivity by Huang et al. (2005). A remarkable example is the study by Xu et al. (1998) in which they showed that nominally “dry” wadsleyite and ringwoodite have substantially (a factor of ~ 300) higher conductivity than “dry” olivine (Fig. 3). We measured the water content in the samples studied by Xu et al. (1998) and noted that a large fraction of the difference in conductivity is due to the difference in water content: wadsleyite and ringwoodite in their samples contain a substantially larger amount of water than olivine, and that the reported large difference in conductivity is mostly due to the difference in water content (Huang et al. 2006). The degree to which water (hydrogen) can be acquired by a sample depends strongly on the hydrogen solubility. For this reason, wadsleyite acquires more hydrogen than olivine, and Fe-rich olivine acquires more water than Fe-poor olivine.

Electrical conductivity of nominally “dry” olivine, wadsleyite, and ringwoodite (from Xu et al. 1998). No water was added, but the FTIR analysis of their samples in my lab showed a substantial amount of water in wadsleyite and ringwoodite. The reported large difference in electrical conductivity is due largely to the difference in water content (Huang et al. 2006)

Another observation is a comparison of nominally “dry” olivine conductivity. Figure 4 summarizes the published results on electrical conductivity of “dry” olivine with different FeO content (modified from Dai and Karato (2014c)). In this Figure, the results from truly dry data are marked. They include the results from room pressure high-temperature studies (Hirsch et al. 1993; Constable et al. 1992) where there is no chance to get a substantial amount of hydrogen, and the results by Dai and Karato (2014c) where the water content of the samples was determined to be small (less than ~ 10 ppm wt).

Electrical conductivity of nominally “dry” olivine with different FeO (Mg#) content. Results shown as “truly dry” are those at room pressure (Constable et al. 1992; Hirsch et al. 1993) and at high pressure by (Dai and Karato 2014c) (shown by solid symbols and solid lines) where the water content of the sample was measured and shown to be small (less than 10 ppm wt). Results shown by “dry?” (Cemič et al. 1980; Omura et al. 1989; Yoshino et al. 2012) are the results at high pressures but the water content of their samples was not measured. The results from these high-pressure studies show much higher electrical conductivity than those of truly dry samples. The most likely reason is the presence of some water (hydrogen) in their samples. OKK: Omura et al. (1989). YMSK: Yoshino et al. (2012). CWH: Cemič et al. (1980). HSD: Hirsch et al. (1993). WMXK: Wang et al. (2006)

Although these truly dry data agree well, much higher and scattered conductivity is observed in the results obtained at high pressures where the water content of the samples was not measured. In these cases, the results obtained at high pressures show much higher conductivity than those for truly dry samples and that the deviation from truly dry data tends to be larger for higher FeO content. It is possible that this large scatter and high conductivity are due to water in their samples. Dissolution of hydrogen into a sample during a high-pressure experimentation is well known, and the tendency is higher for a sample with higher hydrogen solubility. In case of olivine, hydrogen solubility systematically increases with FeO content (Zhao et al. 2004), that is consistent with the trend seen in Fig. 4. However, the water content of samples from these studies was not determined that makes difficult to understand the causes for the discrepancy between these results (“dry?” data in Fig. 4) and the results where water content was shown to be low (“truly dry” data in Fig. 4). It is essential to measure the water content to confirm that the results correspond to “dry” conditions.

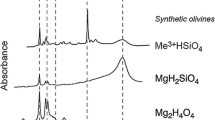

In the similar context, the “dry” samples studied by Yoshino et al. (2008) are not truly dry. Their FTIR spectra for water-poor samples are not clearly shown and it is impossible to quantify the water content in these samples (Fig. 5a). If wadsleyite really contains very low hydrogen content, the peak frequency of infrared absorption moves from ~ 3330 cm− 1 to ~ 3205 cm− 1 or ~ 3620 cm− 1 depending on the oxygen fugacity (Nishihara et al. 2008) (see Fig. 5b). Yoshino et al. (2008)’s IR absorption spectra have poor resolution and such a shift cannot be identified. For wadsleyite, Dai and Karato (2009b) showed that the water content as small as 23 ppm wt (0.0023 wt%) can enhance electrical conductivity (by a factor of ~ 10 at T = 1000 K) compared to truly dry sample that contains water less than 3 ppm wt. The low hydrogen content in wadsleyite can be clearly seen in Fig. 5b from the shift of the peak frequency as demonstrated by Nishihara et al. (2008). In contrast, the infrared absorption spectra published by Yoshino et al. (2008) do not show the details to convincingly show low water content. From their figure, I can only conclude that their “dry” sample has water content less than 0.1 wt% (Fig. 5b). Indeed, Yoshino et al. (2008)’s “dry” wadsleyite has ~ 10 times higher conductivity than our truly dry sample.

A comparison of infrared absorption spectra. a Infrared absorption spectra of wadsleyite from (Dai and Karato 2009b). The peak position of infrared absorption changes at low water content. b Infrared absorption spectra of wadsleyite from Yoshino et al. (2008). There is no evidence for the shift of absorption peak at low water content

The situation is worse for ringwoodite. From the published results of IR absorption spectra, one could roughly estimate the water contents of their “dry” samples by 100–1000 ppm wt (compared to the dry sample studied by Dai and Karato (2009b) (~ 2 ppm wt, see their Fig. 1)).

I should also comment on the water content in samples studied by Poe et al. (2010). Firstly, they measured the water content of samples only after each experiment. Consequently, possible water loss or gain during an experiment cannot be assessed. More importantly, the reported values of water content by Poe et al. (2010) are large (363–2215 ppm wt based on Bell et al. (2003) calibration (121–746 ppm wt by Paterson (1982) calibration)), and most values exceed the solubility limit determined by Kohlstedt et al. (1996) and Zhao et al. (2004) (Fig. 6). For instance, according to Kohlstedt et al. (1996), the solubility of water at 8 GPa and 1373 K is ~ 2500 ppm wt (Bell calibration) (850 ppm wt (Paterson calibration)). Poe et al. (2010) conducted their measurements at P = 8 GP and T = 715–973 K. Under these conditions, the water solubility in olivine is 45–300 ppm wt based on Bell calibration (15–100 ppm wt based on Paterson calibration) (Zhao et al. 2004). It appears that the Poe’s samples were nearly water-saturated at the conditions where they added water (8 GPa, 1373 K), but under the conditions where they measured electrical conductivity, the samples were super-saturated with water. In these cases, behavior of hydrogen during a conductivity measurement could be different from those measurements under the conditions where hydrogen content is below the solubility limit. Indeed, similar studies on olivine single crystals by Yang (2012) and Dai and Karato (2014b) did not show strong anisotropy reported by Poe et al. (2010).

A comparison of water content-temperature conditions of various studies with the solubility of water. Solubility of water in olivine depends strongly on temperature (Zhao et al. 2004). The experimental studies by Yoshino and Poe’s group were all conducted under the conditions where samples are highly super-saturated with water

These observations show that it is essential to measure the water content of a sample both before and after each high-pressure measurement to make sure that the water content of the sample did not change much during an experiment. To be sure, it is also very useful to measure electrical conductivity through a few cycles. If hydrogen loss occurs during the measurement, one would detect hysteresis.

Some theoretical issues

In this section, I will review two theoretical issues in relation to hydrogen-enhanced electrical conductivity. One is the link between diffusion coefficient and electrical conductivity, and another is the concentration dependence of activation energy.

The diffusion versus conductivity discrepancy

Hydrogen-enhanced conductivity is largely caused by diffusion of hydrogen (proton). In these cases, electrical conductivity is related to diffusion coefficient by the Nernst-Einstein relation (e.g., Mott and Gurney 1940), viz.,

where σ is electrical conductivity, D is the diffusion coefficient of relevant charged species, c is the concentration of that species, q is the electric charge of that species, and RT has its usual meaning. This relation means that the temperature dependence of diffusion and conductivity is the same (ignoring 1/T dependence) so is the anisotropy. Similarly, this relation implies that the hydrogen-enhanced conductivity must be linearly proportional to hydrogen content. As I will discuss below, these predictions are not consistent with the experimental observations suggesting that a modification (or a generalization) of the Nernst-Einstein relation is required.

Let us first discuss anisotropy. The results of isotope diffusion of hydrogen by Du Frane and Tyburczy (2012) showed very large anisotropy on diffusion (see also Kohlstedt and Mackwell (1998) and Mackwell and Kohlstedt (1990) who studied chemical diffusion) (Fig. 7a). In contrast, all measurements of electrical conductivity at low temperatures (T < 800 C) show very weak anisotropy (Fig. 7b, e.g., Dai and Karato 2014b; Poe et al. 2010; Yang 2012Footnote 1).

A few examples showing the diffusion-electrical conductivity discrepancy. a Electrical conductivity of olivine single crystals measured at low temperatures (Poe et al. 2010; Yang 2012) showing small anisotropy. b Electrical conductivity of olivine calculated from diffusion coefficients showing high anisotropy and large activation enthalpy. c A comparison of electrical conductivity. WMXK: Wang et al. (2006). YMSK: Yoshino et al. (2009). PRNS: Poe et al. (2010). Yang: Yang (2012). DFT: Du Frane and Tyburczy (2012)

It is also seen that the activation enthalpy (temperature sensitivity) of electrical conductivity is substantially smaller than that of diffusion (Fig. 7c). Karato (2013) developed a theory to explain this. The essence of the theory is that when isotopic diffusion occurs in a material where a given isotope has multiple species with different mobility, then the effective diffusion coefficient corresponding to the isotopic exchange is the harmonic average of various diffusing species for much the same reason as diffusion creep in a compound: in both cases, molar ratios of various species must be maintained to keep a material at thermochemical equilibrium. This model predicts that the effective diffusion coefficient relevant to isotope exchange is given by,

where Disotope is the diffusion coefficient relevant to the isotope exchange, αj is the stoichiometric coefficient of the j-th species and Dj is the diffusion coefficient of the j-th species.

Whereas the contribution from each species to electrical conductivity is given by,

where qj is the electric charge of the j-th species.

In brief, it is the slowest diffusing species that controls the rate of isotope exchange, whereas it is the species that has the large value of diffusivity × concentration that controls electrical conductivity. Interstitial (or “free”) proton is likely the fastest diffusing species at low temperatures, whereas another species such as two protons at M-site (\( {(2H)}_M^{\times } \)) would be the slowest moving species under these conditions. Highly mobile interstitial proton (or “free” proton) likely has nearly isotropic mobility, whereas the mobility of deeply trapped protons at M-site (e.g., \( {(2H)}_M^{\times } \)) is likely highly anisotropic.

This model therefore predicts that the mechanism of conduction changes from nearly isotropic interstitial proton mechanism at low temperature to highly anisotropic \( {(2H)}_M^{\times } \) mechanism at high temperatures. The experimental results by Dai and Karato (2014b) showed a transition from nearly isotropic conductivity at low temperatures to highly anisotropic conductivity at high temperatures, which is consistent with this model (Fig. 8).

Electrical conductivity of olivine single crystals determined under a broad temperature range (from Dai and Karato 2014b). Water content is 460 ppm wt (Paterson calibration). This value is chosen to minimize the extrapolation. YMSK: Yoshino et al. (2009). PRNS: Poe et al. (2010). WMSK: Wang et al. (2006). Yang: Yang (2012). Anisotropy is weak at low temperature but increases at high temperature. Low temperature results agree reasonably well with other results except for Yoshino et al. (2009). Yoshino et al. (2009) shows data on water content after the measurements using two different units in their Table 1 that do not match each other by a factor of 10. I used the one that they recommend (by personal communication))

Parameterization of electrical conductivity: does activation energy depend on water content?

In this section, I will focus on the issues of parameterization of hydrogen-enhanced conductivity with a focus on the formula in which water (hydrogen) content is incorporated in the conductivity equation. Since hydrogen-assisted conductivity occurs due to the dissolution of hydrogen, it is natural to assume that this conductivity is proportional to some power of water dissolved in the mineral, CW, viz.,

where σW is hydrogen-assisted electrical conductivity, AW is a constant, CWo is a reference water content, r is a non-dimensional constant, and \( {H}_W^{\ast } \) is the activation enthalpy. Recall that if one assumes the Nernst-Einstein relationship (Eq. (2)) and all dissolved hydrogen contribute to electrical conductivity equally, then, \( {\sigma}_W={A}_W\cdot \left(\frac{C_W}{C_{W0}}\right)\cdot \exp \left(-\frac{H_W^{\ast }}{RT}\right) \) (i.e., r = 1) with \( {H}_W^{\ast } \) being the activation enthalpy for diffusion.

There have been some suggestions to modify the relation (5) to introduce the dependence of activation enthalpy on water content. The first report was by Yoshino et al. (2008) where they noted that the activation enthalpy decreases with water content and suggested a use of a model proposed by Debye and Conwell (1954), i.e.,

where \( {H}_{Wo}^{\ast } \) is a reference activation enthalpy and α is a positive constant. This relation has been used by Gardés et al. (2014) and Jones (2014) to explain the discrepancies among different reports on hydrogen-assisted electrical conductivity.

As obvious from this formula, the term \( \alpha \cdot {C}_W^{1/3} \) represents the Coulombic energy of the relevant defect (\( {C}_W^{1/3}\propto \frac{1}{\left\langle r\right\rangle } \): 〈r〉 is the mean distance of the charged impurities). In other words, this formula works for a case where relevant species has effective electric charge (charge relative to the perfect crystal) such as a doped semi-conductor. Consequently, if the dominant hydrogen-bearing species is a neutral defect such as \( {(2H)}_M^{\times } \), this equation will not work.

Indeed, the concentration dependence of activation enthalpy was never been clearly demonstrated in hydrous olivine (nor wadsleyite). A case for wadsleyite claimed by Yoshino et al. (2008) was disputed by Karato and Dai (2009) who showed that the concentration dependence reported by Yoshino et al. (2008) was a consequence of the use of an incorrect method of determining the electrical conductivity (see section on Hydrogen loss). Indeed, a later study by Yoshino et al. (2009) using the impedance spectroscopy showed very little dependence of activation enthalpy on water content (see also Dai and Karato 2009b).

The only exception is a study by Poe et al. (2010). Poe et al. (2010) reported unusually strong water content dependence of electrical conductivity in olivine. If one uses a formula (5), one would get r = 2.5–3.6. Poe et al. (2010) also reported strong dependence of activation enthalpy on water content and fitted their result to the relation (6) and estimated the values of α. The values of α they reported far exceed the values estimated in other papers (see Jones 2014). A theory by Debye and Conwell (1954) implies that a constant α depends on the electric charge of the species (proton) and the dielectric constant of the material. Since dielectric constant of a mineral does not change so much among minerals (e.g., Shannon et al. 1992, 1991), α should not depend so much on minerals. The reported values of α for olivine by Poe et al. (2010) are larger than other estimated values by a factor of 10 to 50 that is at odd from the theoretical point of view.

Also even more serious is the fact that in all of their samples, the reported water content exceeds the solubility limit determined by Zhao et al. (2009) particularly when the influence of temperature is included. Nevertheless, Poe et al. (2010) did not report the variation of water content before and after the measurements, nor they checked the hysteresis during their measurements. Consequently, the potential influence of water loss (and/or gain) during the measurements was not addressed in that study, and the validity of their results is highly questionable. Therefore, I conclude that the formula (6) proposed by Yoshino et al. (2008) and used by Gardés et al. (2014) and Jones (2014) has weak theoretical nor experimental support and is likely caused by the use of inappropriate methods in these studies.

In the attempts to “reconcile” different on hydrogen-assisted electrical conductivity in olivine by Gardés et al. (2014) and Jones (2014), the results by Poe et al. (2010) play a key role because these results correspond to the high end of water content. However, as I demonstrated in Fig. 9 and discussions above, Poe et al. (2010)’s results are anomalous and their validity is highly questionable. I consider that an effort to “reconcile” these data including dubious ones like Poe et al. (2010)’s is not warranted. Therefore, I will not consider the relation (6).

Relation between the activation enthalpy and water content in olivine. The data are from Wang et al. (2006), Yoshino et al. (2009), and Poe et al. (2010). No clear trend can be seen except for the results from Poe et al. (2010). The water content dependence of activation enthalpy is also very small for wadsleyite (e.g., Dai and Karato 2009b; Yoshino et al. 2008)

Applications to the asthenosphere and the lithosphere

Conductivity of the asthenosphere: do we need partial melt?

Let me discuss how the laboratory results at high temperatures explain the geophysically inferred electrical conductivity in the asthenosphere. Figure 10 summarizes some of the geophysical models of electrical conductivity in the oceanic regions.

Geophysical models of electrical conductivity in the oceanic upper mantle from the magnetotelluric observations. a Results away from the mid-ocean ridge (from Sarafian et al. 2015). Mid Pacific (70 Myrs old oceanic region). Electrical conductivity increases smoothly with depth without any peak. b Results near the east Pacific Rise (from Evans et al. 2005). There is a peak in conductivity at the top of the asthenosphere. Some anisotropy is also reported (high along the direction of plate motion, low normal to it both in the horizontal plane)

The electrical conductivity of the asthenosphere is in the range of ~ 10− 2 to ~ 10− 1 S/m. When one uses the new results by Dai and Karato (2014b), not much extrapolation is needed, and as summarized in Fig. 8, new results at high temperatures show stronger sensitivity to temperature and much larger degree of anisotropy as compared to the previous results at lower temperatures.

Figure 11a shows the combinations of temperature and water content that are needed to explain geophysically inferred conductivity in the asthenosphere. The results agree well with the water content of the asthenosphere constrained by geochemical observations on the mid-ocean ridge basalts (Dixon et al. 2002; Ito et al. 1983; Saal et al. 2002) except for very high conductivity (~ 0.1 S/m) reported in some regions (e.g., Evans et al. 2005; Naif et al. 2013). A very high conductivity in these latter regions would require somewhat higher mantle temperatures and/or the presence of accumulated melt.

Testing the hydrogen-assisted conductivity model against geophysical observations on the asthenosphere (after Dai and Karato 2014b). a The water content-temperature combinations that explain geophysically inferred conductivity of then asthenosphere (green region is the conductivity of the asthenosphere, brown region is water content of the asthenosphere). b Anisotropy in electrical conductivity. “0” anisotropy means isotropic. “3” means a factor of 3 anisotropy

Figure 11b shows the degree of anisotropy as a function of temperature. Anisotropy is weak at low temperatures, whereas it increases at higher temperatures. If we use a model to calculate the anisotropy from the degree of lattice-preferred orientation inferred from seismic anisotropy (e.g., Simpson and Tommasi 2005), we see that the hydrogen-assisted conduction model provides a reasonable explanation of inferred anisotropy in electrical conductivity.

So I conclude that there is no need for partial melting to explain geophysically inferred electrical conductivity in most of the asthenosphere. I provided a similar discussion on the cause of the seismic wave velocity in the asthenosphere (Karato 2012).

However, a partial melt model for the asthenosphere is still popular to explain high electrical conductivity as well as low seismic wave velocities (e.g., Kawakatsu et al. 2009; Naif et al. 2013; Nakajima et al. 2005; Pommier et al. 2015; Sifré et al. 2014; Yoshino et al. 2006). Below, I will discuss partial melt models in view of both seismological and electrical conductivity observations.

Strong constraints on the partial melt models can be obtained from seismological observations. This is because seismic wave velocities depend strongly on the melt fraction and the melt geometry (the dihedral angle, e.g., Stocker and Gordon 1975; Takei 2002). For a well-known dihedral angle of the olivine-basalt system in the shallow asthenosphere (e.g., Cooper and Kohlstedt 1982; Toramaru and Fujii 1986; Yoshino et al. 2007), one would need a few % of melt to explain 5–10% reduction in seismic wave velocity at the lithosphere-asthenosphere boundary (LAB) if the melt were homogeneously distributed. Such a high homogeneous melt fraction is unlikely in the asthenosphere on the petrological and physical grounds (e.g., Hirschmann 2010; Karato 2014). Consequently, either the melt accumulation at the lithosphere-asthenosphere boundary (LAB) or the presence of melt-rich layers among melt-poor layers needs to be invoked to explain low seismic wave velocity (Fig. 12; e.g., Hirschmann 2010).

The melt accumulation at the LAB would predict a peak in electrical conductivity at the LAB. A peak in conductivity is reported near the ridge (Evans et al. 2005) and near the trench (Naif et al. 2013), but a recent high-resolution MT study using an array of detectors showed that such a peak is not present in the matured oceanic upper mantle (Sarafian et al. 2015). Therefore, I conclude that melt accumulation might occur in some limited regions (see a more detailed discussion in the later part), but the results of high-resolution MT study in a typical matured oceanic upper mantle rules out the melt accumulation model.

Let us now discuss the plausibility of a layered structure model (Fig. 12b). In such a model, it is assumed that melt is not uniformly distributed but is concentrated in thin layers caused by deformation (e.g., Holtzman et al. 2003). The physical properties of such a material can be calculated from the volume fraction of melt-rich layers (f) and the melt fraction (ϕ) in these layers. Given the total melt fraction (ϕo), these two quantities are related (ϕo = fϕ + (1 − f)ϕoo ≈ fϕ (ϕoo: melt fraction in the melt-depleted regions)), and if one specifies the melt fraction of melt-rich layers, then thickness of that layer is fixed and physical properties can be calculated uniquely from the melt fraction in that layer. Therefore, the physical properties of such a layered material can be specified by a single parameter, the melt fraction in the melt-rich layer, ϕ.

Influence on electrical conductivity is somewhat different. Since melt has in general much higher electrical conductivity than (dry) solid, most of electric current flows in the melt. The conductivity of a mixture of two phases depends on the volume fraction and conductivity of each phase, and in most cases, the actual conductivity of a mixture is close to the upper bound of the Hashin-Strikman average (e.g., McLachlan et al. 1990), viz.,

where σ is electrical conductivity of materials containing two different materials, σ2 is the electrical conductivity of a melt-rich layer, σ1 is the electrical conductivity of melt-poor layer (σ2 ≫ σ1), and σm is the electrical conductivity of the melt. Where I used an empirical relation, σ2 ≈ ϕ ⋅ σm.

Note that the conductivity of such a layered structure model does not depend on the fraction of melt-rich layer (f) nor on the melt content in the melt-rich layer, but simply depends on the total melt fraction (ϕo) and the melt conductivity (σm). This is due to the fact that a majority of the electric current goes through the melt. Consequently, electrical conductivity observations do not provide constraints on the layered structure model such as the one proposed by Kawakatsu et al. (2009).

In order to obtain σ =10− 2–10− 1 S/m as required from geophysical observations on the asthenosphere for ϕo =(1–3) × 10− 3 (Hirschmann 2010), one would need σm= 4–140 S/m. Laboratory studies show that these values correspond to basaltic melt with ~ 5–10% water and 10–20% carbon dioxide (e.g., Ni et al. 2011; Sifré et al. 2014). These values far exceed the typical volatile content in the mid-ocean ridge basalt, H2O = 0.05–0.1 wt%, CO2 = 0.005–0.025 wt% (e.g., Saal et al. 2002). However, in regions of incipient melting far away from the mid-ocean ridge, higher amount of volatiles is possible.

The situation is quite different for seismic wave velocity. The velocity of a material containing melt-rich low velocity layers depends strongly on the volume fraction of such layers (f) as well as the melt content in the melt-rich layer (ϕ). Given a bulk melt fraction (ϕo), the velocity of such a layered structure depends strongly on the melt fraction in the melt-rich layer (Fig. 13). If the average melt fraction is as small as 0.1–0.3% as predicted by (Hirschmann 2010), then homogeneously distributed melt cannot explain more than a few % of velocity reduction. If melt were concentrated in thin layers as suggested by Holtzman et al. (2003), it would explain a large velocity reduction (Kawakatsu et al. 2009). However, such a model requires a very specific value of melt fraction in melt-rich layers (5–10% velocity reduction, one must have a very specific melt fraction in melt-rich layer (14 (± 1) %; Fig. 13). There is no theory that predicts that the melt fraction of a melt-rich layer should be 14 (± 1) %. Therefore, I conclude that partial melt model is difficult to support based on the mineral physics considerations.

Testing a model of layered structure (Fig. 11b) for seismic wave velocity (modified from Karato 2014). The relations, \( \frac{\Delta V}{V}=\frac{1}{2}\frac{\phi_o}{\phi }{\left(\frac{1-\frac{M_2}{M_1}}{\sqrt{M_2/{M}_1}}\right)}^2 \) (Karato 2008) and \( \frac{M_2}{M_1}=1-A\cdot \phi \) (A = 0.067, Takei 2002) are used. The melt fraction of the melt-rich layers needs to be in a very narrow range (14 ± 1%) in order to explain the observed 5–10% velocity drop at the lithosphere-asthenosphere boundary for the net melt fraction of ϕo= 0.001–0.003 (Hirschmann 2010)

An exception is the high conductivity near the top of the asthenosphere near ocean ridges (Evans et al. 2005) or near the trench (Naif et al. 2013). The electrical conductivity in these regions is very high (~ 0.1 S/m), and in these regions, the electrical conductivity has a peak near the top of the asthenosphere. These features are not easy to be explained by the hydrogen model (to explain conductivity of ~ 0.1 S/m, one would need unusually high temperature and/or high water content; see Fig. 11a). Melt accumulation near the lithosphere-asthenosphere boundary might cause such high electrical conductivity in these regions. Indeed evidence of accumulated melt at the lithosphere-asthenosphere boundary near the trench is reported by Yamamoto et al. (2014). The influence of partial melt on electrical conductivity might be important in these regions.

However, a challenge in the accumulated melt model is to explain the geophysically inferred anisotropy in conductivity quantitatively. Laboratory studies show evidence of anisotropic geometry of melt by shear deformation causing anisotropy in electrical conductivity (Pommier et al. 2015; Zhang et al. 2014). However, the degree of anisotropy depends on the geometry of melt, and the melt geometry in a deformed rock likely depends on the magnitude of stress and grain-size. Laboratory studies are conducted on fine-grained rocks at high stress. In order to apply laboratory data to Earth’s interior where stress is much less and grain-size is larger, one needs extrapolation. However, scaling law for the melt geometry is not well known. In contrast, extrapolation is not needed to explain anisotropy by the hydrogen model as far as the degree of lattice-preferred orientation is constrained by seismological observations (Fig. 11b).

An additional test for these models would be to detect the contrast in electrical conductivity between the horizontal plane and the vertical plane. A hydrogen model predicts only weak anisotropy between vertical and horizontal planes, whereas a melt-rich layer model would predict much lower conductivity in the vertical plane than in the horizontal plane.

Finally, some contribution from ionic conductivity due to Mg (Fe) diffusion is expected at high temperature as first pointed out by (Karato 1973). In view of the known effect of water to enhance Mg (Fe) diffusion (Hier-Majumder et al. 2005), there is some potential for this mechanism to make contribution in the asthenosphere. However, negative pressure effects (positive activation volume) on Mg (Fe) diffusion (Karato 1973; Misener 1974) as compared to nearly zero pressure effect on hydrogen-enhanced conductivity (Dai and Karato 2014a) will make the contribution by Mg (Fe) diffusion less important. It may also be noted that the anisotropy of conductivity by Mg (Fe) diffusion (e.g., Buening and Buseck 1973) is different from the anisotropy of hydrogen-enhanced conductivity at high temperatures (Dai and Karato 2014b) and is not consistent with the geophysically inferred anisotropy if anisotropy in Mg (Fe) diffusion is the same between dry and wet conditions.

Conductivity of the lithosphere: can olivine explain it?

The lithosphere is a region of low temperature and therefore no melt exists. And most of low temperature measurements can be directly applied to the lithosphere. The continental lithosphere is depleted with incompatible elements (e.g., Carlson et al. 2005), and it was often suggested that low conductivity of the continental lithosphere is consistent with dry composition (e.g., Hirth et al. 2000).

However, various MT studies show that the actual electrical conductivity of the continental lithosphere is not as low as truly dry model (e.g., Evans et al. 2011; Selway et al. 2014). Indeed, mantle xenoliths show not very low water content (Demouchy and Bolfan-Casanova 2016; Peslier et al. 2010; Warren and Hauri 2014) and the influence of metasomatism may be important.

Under relatively low water content (water fugacity), water is partitioned more to orthopyroxene than to olivine (Dai and Karato 2009a; Sakurai et al. 2014). In these cases, orthopyroxene would have much higher electrical conductivity than olivine, and therefore, the volume fraction and the connectivity of orthopyroxene will have an important effect on the bulk electrical conductivity.

In some regions of the continent (e.g., the region beneath Bushveld in South Africa), electrical conductivity is unusually high: ~ 1 S/m at 50–150 km depth (e.g., Evans et al. 2011). Such high conductivity in that depth range (temperature is 500–1000 °C) cannot be explained by olivine alone. Possible influence of minor phases such as graphite (e.g., Frost et al. 1989; Wang et al. 2013) and/or sulphides (e.g., Evans et al. 2011) may be required to explain such anomalies.

Concluding remarks

One of the most important conclusions of the present review is the fact that when one is dealing with a delicate physical property such as hydrogen-assisted electrical conductivity, one must be extremely cautious in conducting an experimental study and interpreting the results. I showed a few cases where unrecognized factors such as hydrogen addition in nominally “dry” experiments modifies the values of conductivity more than a factor of 100. If one includes the results of an experimental study in which these necessary steps to assure the validity of the results were not taken, it is impossible to come up with any physically plausible model. It is essential to select reliable results to come up with any meaningful conclusions. Accepting all the published results and trying to come up with a “unified model” that explains all of them is not warranted.

It is also shown that there are multiple hydrogen-related species in a given mineral with different mobility. In these cases, experimental results obtained at limited conditions (e.g., low temperatures) cannot be extrapolated to other conditions (e.g., higher temperatures). A reconnaissance study to investigate the influence of multiple mechanisms of conduction in hydrous olivine was made by Dai and Karato (2014b) where conductivity was measured in a broad temperature range by minimizing the hydrogen loss.

The results of experimental studies on hydrogen-enhanced conductivity at high temperatures provide reasonable explanation of some of the key geophysical observations (Fig. 10). However, this work is highly preliminary, and much more needs to be studied. They include the further characterization of hydrogen-assisted conductivity in olivine including the study on the sensitivity to water content and its extension to deep mantle minerals.

Recently, Sun et al. (2015) reported the experimental results on the H-D isotope diffusion in ringwoodite. Further studies on wadsleyite and comparison to electrical conductivity will be helpful in understanding the role of hydrogen in electrical conductivity.

Perhaps the largest remaining issue in hydrogen-assisted electrical conductivity is the role of this process in the lower mantle minerals. If one uses an analogy with ceramics, it may be expected that substantial amount of hydrogen can be dissolved in bridgmanite that might enhance electrical conductivity (Navrotsky 1999). However, the situation is not simple. Previous studies on hydrogen solubility in bridgmanite showed a broad range of results (e.g., Kaminsky 2018) that is partly caused by the presence or absence of hydrogen-rich inclusions. Also lower mantle minerals (bridgmanite and ferropericlase) contain much larger amount of ferric Fe and other point defects than in shallow mantle minerals such as olivine (e.g., Otsuka and Karato 2015). Consequently, it is not clear if hydrogen has a large effect on any defect-related properties.

Several studies have been conducted on the electrical conductivity in lower mantle minerals (Dobson et al. 1997; Katsura et al. 1998; Peyronneau and Poirier 1989). However, in none of the existing experimental studies, hydrogen content in the lower mantle samples was measured, and also in all of them, electrical conductivity was measured using DC technique. Some hydrogen might have been present in these samples, but when DC technique is used the influence of hydrogen cannot be determined because hydrogen should have lost from the electrodes. Determining the role of hydrogen in the lower mantle mineral is important to place constraint on the global water circulation (Karato 2011, 2015b).

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Notes

Poe et al. (2010) claimed high anisotropy, but their data do not show high anisotropy unless their data are extrapolated (their data show highly anisotropic activation enthalpy). For more discussions on Poe et al. (2010), see section of Parameterization of electrical conductivity

References

Bell DR, Rossman GR, Maldener J, Endisch D, Rauch F (2003) Hydroxide in olivine: a quantitative determination of the absolute amount and calibration of the IR spectrum. J Geophys Res 108. https://doi.org/10.1029/2001JB000679

Buening DK, Buseck PR (1973) Fe-Mg interdiffusion in olivine. J Geophys Res 78:6852–6862

Carlson RW, Pearson DG, James DE (2005) Physical, chemical, and chronological characteristics of continental mantle. Rev Geophys 43:2004RG000156

Cemič L, Will G, Hinze E (1980) Electrical conductivity measurements on olivines Mg2SiO4-Fe2SiO4 under defined thermodynamic conditions. Phys Chem Miner 6:95–107

Constable S, Shankland TG, Duba A (1992) The electrical conductivity of an isotropic olivine mantle. J Geophys Res 97:3397–3404

Cooper RF, Kohlstedt DL (1982) Interfacial energies in the olivine-basalt system. In: Akimoto S, Manghnani MH (eds) High pressure research in geophysics. Venter for Academic Publication, Tokyo, pp 217–228

Dai L, Karato S (2009a) Electrical conductivity of orthopyroxene: implications for the water content of the asthenosphere. Proc Jpn Acad 85:466–475

Dai L, Karato S (2009b) Electrical conductivity of wadsleyite under high pressures and temperatures. Earth Planet Sci Lett 287:277–283

Dai L, Karato S (2014a) The effect of pressure on hydrogen-assisted electrical conductivity of olivine. Phys Earth Planet Inter 232:51–56

Dai L, Karato S (2014b) High and highly anisotropic electrical conductivity of the asthenosphere due to hydrogen diffusion in olivine. Earth Planet Sci Lett 408:79–86

Dai L, Karato S (2014c) The influence of FeO and H content on the electrical conductivity of olivine: applications to terrestrial planets with differnt FeO content. Earth Planet Sci Lett 237:73–79

Debye PP, Conwell EM (1954) Electrical conductivity of N-type germanium. Phys Rev 93:693–706

Demouchy S, Bolfan-Casanova N (2016) Distribution and transport of hydrogen in the lithospheric mantle: a review. Lithos 240–243:402–425

Dixon JE, Leist L, Langmuir J, Schiling JG (2002) Recycled dehydrated lithosphere observed in plume-influenced mid-ocean-ridge basalt. Nature 420:385–389

Dobson DP, Richmond NC, Brodholt JP (1997) A high-temperature electrical conduction mechanism in the lower mantle phase. Science 275:1779–1781

Du Frane WL, Tyburczy JA (2012) Deuterium-hydrogen interdiffusion in olivine: implications for point defects and electrical conductivity. Geochem Geophys Geosyst 13. https://doi.org/10.1029/2011GC003895

Evans RL, Hirth G, Baba K, Forsyth DW, Chave A, Makie R (2005) Geophysical evidence from the MELT area for compositional control on oceanic plates. Nature 437:249–252

Evans RL, Jones AG, Garcia X, Muller M, Hamilton M, Evans S, Fourie CJS (2011) Electrical lithosphere beneath the Kaapvaal craton, southern Africa. J Geophys Res 116. https://doi.org/10.1029/2010JB007883

Frost BR, Fyfe WS, Tazaki K, Chan T (1989) Grain-boundary graphite in rocks and implications for high electrical conductivity in the lower crust. Nature 340:134–136

Gardés E, Gaillard F, Tarits P (2014) Toward a unified hydrous olivine electrical conductivty law. Geochem Geophys Geosyst 15:4984–5000

Hier-Majumder S, Anderson IM, Kohlstedt DL (2005) Influence of protons on Fe-Mg interdiffusion in olivine. J Geophys Res 110:2004JB003292

Hirsch LM, Shankland TJ, Duba A (1993) Electrical conduction and polaron mobility in Fe-bearing olivine. Geophys J Int 114:36–44

Hirschmann MM (2006) Water, melting, and the deep Earth H2O cycle. Annu Rev Earth Planet Sci 34:629–653

Hirschmann MM (2010) Partial melt in the oceanic low velocity zone. Phys Earth Planet Inter 179:60–71

Hirth G, Evans RL, Chave AD (2000) Comparison of continental and oceanic mantle electrical conductivity: is Archean lithosphere dry? Geochem Geophys Geosyst 1. https://doi.org/10.1029/2000GC000048

Holtzman BK, Kohlstedt DL, Zimmerman ME, Heidelbach F, Hiraga K, Hustoft J (2003) Melt segregation and strain partitioning: implications for seismic anisotropy and mantle flow. Science 301:1227–1230

Houser C (2016) Global seismic data reveal little water in the mantle transition zone. Earth Planet Sci Lett 448:94–101

Huang X, Xu Y, Karato S (2005) Water content of the mantle transition zone from the electrical conductivity of wadsleyite and ringwoodite. Nature 434:746–749

Huang X, Xu Y, Karato S (2006) A wet mantle conductor? (Reply). Nature 439:E3–E4

Ito E, Harris DM, Anderson AT (1983) Alteration of oceanic crust and geologic cycling of chlorine and water. Geochem Cosmochem Acta 47:1613–1624

Jones AG (2014) Reconciling different equations for proton conduction using the Meyer-Neldel compensation rule. Geochem Geophys Geosyst 15:337–349

Kaminsky FV (2018) Water in the Earth’s lower mantle. Geochem Int 56:1117–1134

Karato S (1973) Electrical conductivity of rock forming minerals, on the electronic states in minerals. The GDP Committee of Japan, Iiyama, pp 1–22

Karato S (1990) The role of hydrogen in the electrical conductivity of the upper mantle. Nature 347:272–273

Karato S (1995) Effects of water on seismic wave velocities in the upper mantle. Proc Jpn Acad 71:61–66

Karato S (2008) Deformation of earth materials: introduction to the rheology of the solid earth. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Karato S (2011) Water distribution across the mantle transition zone and its implications for global material circulation. Earth Planet Sci Lett 301:413–423

Karato S (2012) On the origin of the asthenosphere. Earth Planet Sci Lett 321/322:95–103

Karato S (2013) Theory of isotope diffusion in a material with multiple-species and its implications for hydrogen-enhanced electrical conductivity in olivine. Phys Earth Planet Inter 219:49–54

Karato S (2014) Does partial melting explain geophysical anomalies? Phys Earth Planet Inter 228:300–306

Karato S (2015a) Some notes on hydrogen-related point defects and their role in the isotope exchange and electrical conductivity in olivine. Phys Earth Planet Inter 248:94–98

Karato S (2015b) Water in the evolution of the Earth and other terrestrial planets. In: Schubert G (ed) Treatise on Geophysics. Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp 105–144

Karato S, Dai L (2009) Comments on “Electrical conductivity of wadsleyite as a function of temperature and water content” by Manthilake et al. Phys Earth Planet Inter 174:19–21

Karato S, Wang D (2013) Electrical conductivity of minerals and rocks. In: Karato S (ed) Physics and Chemistry of the Deep Earth. Wiley-Blackwell, New York, pp 145–182

Katsura T, Sato K, Ito E (1998) Electrical conductivity of silicate perovskite at lower-mantle conditions. Nature 395:493–495

Kawakatsu H, Kumar P, Takei Y, Shinohara M, Kanazawa T, Araki E, Suyehiro K (2009) Seismic evidence for sharp lithosphere-asthenosphere boundaries of oceanic plates. Science 324:499–502

Kawamoto T, Hirose K (1994) Au-Pd sample containers for melting experiments on iron and water bearing systems. Eur J Mineral 6:381–385

Kohlstedt DL, Keppler H, Rubie DC (1996) Solubility of water in the α, β and γ phases of (Mg,Fe)2SiO4. Contrib Mineral Petrol 123:345–357

Kohlstedt DL, Mackwell SJ (1998) Diffusion of hydrogen and intrinsic point defects in olivine. Z Phys Chem 207:147–162

Mackwell SJ, Kohlstedt DL (1990) Diffusion of hydrogen in olivine: implications for water in the mantle. J Geophys Res 95:5079–5088

Manthilake MAGM, Matsuzaki T, Yoshino T, Yamashita S, Ito E, Katsura T (2009) Electrical conductivity of wadsleyite as a function of temperature and water content. Phys Earth Planet Inter 174:10–18

McLachlan DS, Blaszkiewicz M, Newnham RE (1990) Electrical resistivity of composite. J Am Ceram Soc 73:2187–2203

Meier U, Trampert J, Curtis A (2009) Global variations of temperature and water content in the mantle transition zone from higher mode surface waves. Earth Planet Sci Lett 282:91–101

Misener DJ (1974) Cationic diffusion in olivine to 1400o C and 35 kbar. In: Hofmann AW, Giletti BJ, Yorder HS Jr, Yund RA (eds) Geochemistry and reaction kinetics. Carnegie Institution of Washington, Washington DC, pp 117–129

Mott NF, Gurney RW (1940) Electronic processes in ionic crystals. Dover, New York

Naif S, Key K, Constable S, Evans RL (2013) Melt-rich channel observed at the lithosphere-asthenosphere boundary. Nature 495:356–359

Nakajima J, Takei Y, Hasegawa A (2005) Quantitative analysis of the inclined low-velocity zone in the mantle wedge of northeastern japan: a systematic change of melt-filled pore shape with depth and its implications for melt migration. Earth Planet Sci Lett 234:59–70

Navrotsky A (1999) A lesson from ceramics. Science 284:1788–1789

Ni H, Keppler H, Behrens H (2011) Electrical conductivity of hydrous basaltic melts: implications for partial melting in the upper mantle. Contrib Mineral Petrol 162:637–650

Nishihara Y, Shinmei T, Karato S (2008) Effects of chemical environments on the hydrogen-defects in wadsleyite. Am Mineral 93:831–843

Omura K, Kurita K, Kumazawa M (1989) Experimental study of pressure dependence of electrical conductivity of olivine at high temperatures. Phys Earth Planet Inter 57:291–303

Otsuka K, Karato S (2011) Control of the water fugacity at high pressures and temperatures: applications to the incorporation mechanisms of water in olivine. Phys Earth Planet Inter 189:27–33

Otsuka K, Karato S (2015) The influence of ferric iron and hydrogen on Fe-Mg interdiffusion in ferropericlase in the lower mantle. Phys Chem Miner 42:261–273

Paterson MS (1982) The determination of hydroxyl by infrared absorption in quartz, silicate glass and similar materials. Bull Mineral 105:20–29

Pearson DG, Brenker FE, Nestola F, McNeill J, Nasdala L, Hutchison MT, Matveev S, Mather K, Silversmit G, Schmitz S, Vekemans B, Vincze L (2014) Hydrous mantle transition zone indicated by ringwoodite included within diamond. Nature 507:221–224

Peslier AH, Woodland AB, Bell DR, Lazarov M (2010) Olivine water contents in the continental lithosphere and the longivity of cratons. Nature 467:78–83

Peyronneau J, Poirier J-P (1989) Electrical conductivity of the material of the Earth’s lower mantle. Nature 365:537–539

Poe B, Romano C, Nestola F, Smyth JR (2010) Electrical conductivity anisotropy of dry and hydrous olivine at 8 GPa. Phys Earth Planet Inter 181:103–111

Pommier A, Leinenweber K, Kohlstedt DL, Qi C, Garnero EJ, Mackwell SJ, Tyburczy JA (2015) Experimental constraints on the electrical anisotropy of the lithosphere-asthenosphere system. Nature 522:202–206

Saal AE, Hauri EH, Langmuir CH, Perfit MR (2002) Vapour undersaturation in primitive mid-ocean-ridge basalt and the volatile content of Earth’s upper mantle. Nature 419:451–455

Sakurai M, Tsujino N, Sakuma H, Kawamura K, Takahashi E (2014) Effects of Al content on water partitioning between orthopyroxene and olivine: implications for lithosphere-asthenosphere boundary. Earth Planet Sci Lett 400:284–291

Sarafian E, Evans RL, Collins JA, Elsenbeck J, Gaetani GA, Gaherty JB, Hirth G, Lizarralde D (2015) The electrical structure of the central Pacific upper mantle constrained by the NoMelt experiment. Geochem Geophys Geosyst 16. https://doi.org/10.1002/2014GC005709

Schmandt B, Jacobsen SD, Becker TW, Liu Z, Dueker KG (2014) Dehydration melting at the top of the lower mantle. Science 344:1265–1268

Selway K, Yi J, Karato S (2014) Water content for the Tanzanian lithosphere from magnetotelluric data: implications for cratonic growth and stability. Earth Planet Sci Lett 388:175–186

Shannon RD, Dickinson JE, Rossman GR (1992) Dielectric constant of crystalline and amorphous spodumene, anorthite and diopside and the oxide additivity rule. Phys Chem Miner 19:148–156

Shannon RD, Subramanian MA, Hosoya S, Rossman GR (1991) Dielectric constants of tephroite, fayalite and olivine and the oxide additivity rule. Phys Chem Miner 18:1–6

Sifré D, Gardés E, Massuyeau M, Hashin L, Hier-Majumder S, Gaillard F (2014) Electric conductivity during incipient melting in the oceanic low-velocity zone. Nature 509:81–85

Simpson F, Tommasi A (2005) Hydrogen diffusivity and electrical anisotropy of a peridotite mantle. Geophys J Int 160:1092–1102

Stocker RL, Gordon RB (1975) Velocity and internal friction in partial melts. J Geophys Res 80:4828–4836

Sun W, Yoshino T, Sakamoto N, Yurimoto H (2015) Hydrogen self-diffusivity in single crystal ringwoodite: implications for water content and distribution in the mantle transition zone. Geophys Res Lett 42:6582–6589

Takei Y (2002) Effect of pore geometry on Vp/Vs: from equilibrium geometry to crack. J Geophys Res 107. https://doi.org/10.1029/2001JB000522

Toramaru A, Fujii N (1986) Connectivity of melt phase in a partially molten peridotite. J Geophys Res 91:9239–9252

Wang D, Karato S, Jiang Z (2013) An experimental study of the influence of graphite on the electrical conductivity of olivine aggregate. Geophys Res Lett 40:2028–2032

Wang D, Mookherjee M, Xu Y, Karato S (2006) The effect of water on the electrical conductivity in olivine. Nature 443:977–980

Wang W, Walter MJ, Peng Y, Redfern S, Wu Z (2019) Contrasting olivine abundance and water content of hte mantle at the 410-km discontinuity from the ealsticity of olivine and wadsleyite. Earth Planet Sci Lett 519:1–11

Warren JM, Hauri EH (2014) Pyroxenes as tracers of mantle water variations. J Geophys Res 119:1851–1881

Xu Y, Poe BT, Shankland TJ, Rubie DC (1998) Electrical conductivity of olivine, wadsleyite, and ringwoodite under upper-mantle conditions. Science 280:1415–1418

Yamamoto J, Korenaga J, Hirano N, Kagi H (2014) Melt-rich lithosphere-asthenosphere boundary inferred from petit-spot volcanoes. Geology 42:967–970

Yang X (2012) Orientation-related electrical conductivity of hydrous olivine, clinopyroxene and plagioclase and implications for the structure of the lower continental crust and uppermost mantle. Earth Planet Sci Lett 317/318:241–250

Yoshino T (2010) Laboratory electrical conductivity measurement of mantle minerals. Surv Geophys 31:163–206

Yoshino T, Katsura T (2013) Electrical conductivity of mantle minerals: Role of water in conductivity anomalies. Annu Rev Earth Planet Sci 41:605–628

Yoshino T, Manthilake G, Matsuzaki T, Katsura T (2008) Dry mantle transition zone inferred from the conductivity of wadsleyite and ringwoodite. Nature 451:326–329

Yoshino T, Matsuzaki T, Shatskiy A, Katsura T (2009) The effect of water on the electrical conductivity of olivine aggregates and its implications for the electrical structure of the upper mantle. Earth Planet Sci Lett 288:291–300

Yoshino T, Matsuzaki T, Yamashita S, Katsura T (2006) Hydrous olivine unable to account for conductivity anomaly at the top of the asthenosphere. Nature 443:974–976

Yoshino T, Nishihara Y, Karato S (2007) Complete wetting of olivine grain-boundaries by a hydrous melt near the mantle transition zone. Earth Planet Sci Lett 256:466–472

Yoshino T, Shimojuku A, Shan S, Guo X, Yamazaki D, Ito E, Higo Y, Funakoshi K (2012) Effect of temperature, pressure and iron content on the electrical conductivity of olivine and its high-pressure polymorphs. J Geophys Res 117:2011JB008774

Zhang B, Yoshino T, Yamazaki D, Manthilake G, Katsura T (2014) Electrical conductivity anisotropy in partially molten peridotite under shear deformation. Earth Planet Sci Lett 405:98–109

Zhao Y-H, Ginsberg SB, Kohlstedt DL (2004) Solubility of hydrogen in olivine: dependence on temperature and iron content. Contrib Mineral Petrol 147:155–161

Zhao Y-H, Zimmerman ME, Kohlstedt DL (2009) Effect of iron content on the creep behavior of olivine: 1. Anhydrous conditions. Earth Planet Sci Lett 287:229–240

Acknowledgements

This study is supported partly by Chinese Academy of Sciences and National Science Foundation of United States. I thank the collaborators including Yousheng Xu, Xiaoge Huang, Duojun Wang, Lidong Dai, and Mainak Mookherjee. Jill VanTongeren helped me to understand the petrological observations on the Bushveld region in South Africa. Xiaozhi Yang provided helpful reviews on this paper.

Funding

This research was funded partly by the National Science Foundation of United States of America with the grant # EAR-1764271.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The author read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ information

SK obtained a PhD in geophysics in 1977 at the University of Tokyo. Since then, he worked as a faculty member at the University of Tokyo, University of Minnesota and Yale University. His studies focus on the physical and chemical properties of Earth materials as related to the dynamics and evolution of Earth and planets. He is a member and fellow of JpGU, AGU, and MSA.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author declares that he has no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Submitted to Progress in Earth and Planetary Science as a review paper.

This paper was originally submitted for publication as a chapter in a book “Water in the Earth” (edited by K. Mibe and J. Kasaraha) in 2016 and accepted for publication on July 12, 2017. However, due to the substantial delay of publication, I requested withdrawal of the paper and obtained the permission of editors. This is an essentially identical manuscript with a few modifications to include some new progress since 2016.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Karato, Si. Some remarks on hydrogen-assisted electrical conductivity in olivine and other minerals. Prog Earth Planet Sci 6, 55 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40645-019-0301-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published: