Abstract

Background

As nonionic surfactants derived from naturally renewable resources, sugar fatty acid esters (SFAEs) have been widely utilized in food, cosmetic, and pharmaceutical industries.

Results

In this study, six enzymes were screened as catalyst for synthesis of glucose laurate. Aspergillus oryzae lipase (AOL) and Aspergillus niger lipase (ANL) yielded conversions comparable to the results obtained by commercial enzymes such as Novozyme 435 and Lipozyme TLIM. The productivity obtained by AOL catalysis in anhydrous 2–methyl–2–butanol (2M2B) (38.7 mmol/L/h and 461.0 μmol/h/g) was much higher than the other literature results. Factors affecting the synthetic reaction were investigated, including water content, enzyme amount, substrate concentrations and reaction temperature. The process was greatly improved by applying the Box-Behnken design of response surface methodology (RSM). Solubilities of glucose in 14 different organic solvents were determined, which were found to be closely associated with the polarity of the solvents.

Conclusions

Aspergillus oryzae lipase is a promising enzyme capable of efficiently catalyzing the synthesis of sugar fatty acid esters with excellent productivity.

Aspergillus oryzae lipase-catalyzed synthesis of sugar fatty acid esters with superior productivity

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Sugar fatty acid esters (SFAEs) are nonionic surfactants which can be produced from naturally renewable resources: carbohydrates (e.g., glucose and sucrose) and fatty acids (e.g., lauric and palmitic acids). SFAEs are tasteless, odorless, nontoxic, nonirritant, and biodegradable; their functional properties such as critical micelle concentration (CMC) and hydrophilic–lipophilic balance (HLB) can be altered over a broad range by tuning the constitutive sugar and fatty acid moieties of the sugar esters, and some of them also possess insecticidal (Puterka et al. 2003) and antimicrobial (Ferrer et al. 2005) activities. All these advantageous features have made SFAEs attractive for use in food, cosmetic, and pharmaceutical industries (Ye and Hayes 2014; Gumel et al. 2011; Kobayashi 2011; Chen et al. 2007).

Enzymatic preparation of sugar esters in organic media has been proved to be superior to the currently dominating chemical synthesis in terms of mild reaction conditions, simple operational procedures, high productivity, excellent regioselectivity, and easy product separation (Ye and Hayes 2014; Gumel et al. 2011; Kobayashi 2011; Chen et al. 2007). The synthetic reaction is normally performed in an organic solvent such as tert-butanol and 2-methyl-2-butanol (2M2B) (Ferrer et al. 2000, 2005; Ye and Hayes 2014; Gumel et al. 2011; Kobayashi 2011; Ikeda and Klibanov 1993; Flores et al. 2002; Pöhnlein et al. 2014; Walsh et al. 2009; Cao et al. 1996).

In terms of enzyme selection, among different lipases (EC 3.1.1.3) that have been tested, Novozym 435 from Novozyme (Candida antarctica lipase B immobilized on acrylic resin) is the most popular one for catalyzing sugar ester synthesis (Ferrer et al. 2005; Ye and Hayes 2014; Gumel et al. 2011; Kobayashi 2011; Flores et al. 2002; Pöhnlein et al. 2014; Cao et al. 1996; Lin et al. 2015). It is necessary to search for some other lipases that are cheap and catalytically efficient for this application.

Factors affecting the synthetic process include substrate concentrations, enzyme amount, reaction temperature, etc. The traditional one-variable-at-a-time optimization approach is not sufficient to maximize the conversion because it is not only laborious and time-consuming, but also cannot guarantee determination of optimal conditions due to the fact that possible interactions among various operational factors have not been considered. The use of the response surface methodology (RSM) as a tool for experimental design and optimization has been applied to a variety of processes because it can enable the building of models and the evaluation of the significance of the different factors considered as well as their interactions (Bezerra et al. 2008). With the aid of experimental design via RSM, optimal conditions can be obtained and optimization achieved by running only a small number of experimental trials.

In this current study, synthesis of glucose laurate by transesterification in 2M2B between d-glucose and vinyl laurate was taken as a model reaction to demonstrate that Aspergillus oryzae lipase (AOL) is a promising catalyst for SFAE synthesis, and Box-Behnken design (BBD) of response surface methodology (RSM) was successfully applied to improve the conversion and productivity.

Materials and methods

Materials

Novozym 435 and Lipozyme TLIM were purchased from Novozymes (China) Investment Co., Ltd. Lipases from Penicillium expansum (PEL), Rhizopus chinensis (RCL), A. oryzae (AOL) and A. niger (ANL), all produced by spraying the concentrated supernatant from fermentation with addition of a certain amount of starch as a thickening agent, were kindly donated by Shenzhen Leveking Bioengineering Co. Ltd., Shenzhen, China. Vinyl laurate was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich China Inc. α-d-Glucose, lauric acid, molecular sieves (4 Å), and all other reagents used were of analytical grade from local manufacturers in China.

Dissolution and solubility of glucose

Different methods of dissolving glucose in organic solvents have been tested, which include agitation, vortex mixing, sonication, microwave, and their combinations, and the one that yielded the fastest dissolution turned out to be a combination of vortex mixing and incubating/shaking. Glucose (100 mg) was added to a test tube containing 2.0 ml of a given solvent (dried with molecular sieves), followed by vortex mixing for 5 min and then shaken in an incubator/shaker at 30 °C and 220 rpm for 12 h. After settling at room temperature (25 °C) for 30 min and then centrifugation at 6000 rpm for 5 min, the supernatant was obtained for determining the glucose solubility by using the dinitrosalicylic acid (DNS) method (Miller 1959). All solubility tests were performed at least three times subjected to less than 5 % error.

Enzymatic reaction

A typical reaction was carried out by adding 0.27 g glucose (corresponding to 0.3 mol−1 of the reaction system, but only partially dissolved) to 5.0 ml 2M2B (dried over molecular sieves for over a week prior to use) containing 0.3 M vinyl laurate (totally dissolved) and 1.0 g 4Å molecular sieves. After vortex mixing for 5 min to maximize the glucose dissolution in the solvent, 0.5 g of the enzyme was added, and the flask was placed in an incubator/shaker with agitation of 300 rpm at 40 °C to start the reaction. Periodically, a 100 µl sample was taken for HPLC analysis (Lin et al. 2015). The conversion was calculated based on the total amount of glucose added to the reaction system. In order to optimize the reaction conditions, the effect of each affecting factor (water content, enzyme amount, reaction temperature and substrate concentrations) was studied independently, i.e., to obtain the optimum for one factor at a time while keeping others constant. The product is 6-O-lauroyl-d-glucopyranose, which has been verified by using HPLC and structural analyses with NMR, IR, and MS (Lin et al. unpublished results). All conversion results were subject to less than 10 % error.

RSM experimental design

Three factors, namely reaction temperature, enzyme amount, and molar ratio of the substrates (VL/Glc), were selected for optimization. The appropriate range for each variable was selected based on the single-factor experiments (see “Enzymatic reaction” section). Then a 3–factor–3–level–Behnken design (BBD) of response surface methodology (RSM) was carried out using Design-Expert 8.0.6, a DOE software developed by Stat-Ease, Inc. Experimental results were analyzed by applying ANOVA (analysis of variance) technique implemented in the Design-Expert software.

Results and discussion

Solubility of glucose in different organic solvents

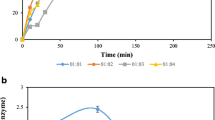

Solubility of glucose has been determined in 14 different organic solvents. The sugar dissolved fairly well in alcohols (e.g., 45.2 mM in methanol) while an almost negligible solubility was obtained in all the four alkanes tested (e.g., hexane, cyclohexane, isooctane and heptane). This is easily understood when taking the “likes dissolve likes” principle into consideration. Glucose is a polar molecule with a polyol structure; thus, polar solvents are expected to facilitate glucose dissolution. Indeed, the glucose solubilities obtained in our study are well associated with the solvent polarities (Fig. 1a); here the polarity of a solvent is represented by its E T (30) value, the molar transition energy of a negatively solvatochromic pyridinium N–phenolate betaine dye (as a probe molecule) dissolved in the solvent (Reichardt 1994). An excellent correlation can also be observed when plotting the glucose solubility data against the log P values of the solvents (Fig. 1b). Here P is the partition coefficient of a solvent in an octanol/H2O biphasic system, which can be used to represent the hydrophobicity of the solvent (Laane et al. 1987). The correlation between glucose solubility and log P is reasonable, because the hydrophobicity of a solvent always tends to be inversely correlated with its polarity. However, no such relationship was observed in the study conducted by Cao et al. 1996 and Degn and Zimmermann 2001, who have determined the glucose solubility in 9 and 11 organic solvents, respectively.

For our reaction involving two substrates of opposite polarity (i.e., the hydrophilic sugar and the hydrophobic fatty acid), an appropriate solvent has to be selected based on a compromise between the two solubilities, while meanwhile the enzyme compatibility and environmental and health risks have also to be considered. Tertiary alcohols such as tert-butanol and 2M2B have been considered as good candidates for this application (Ferrer et al. 2005; Ye and Hayes 2014; Gumel et al. 2011; Kobayashi 2011; Ikeda and Klibanov 1993; Flores et al. 2002; Pöhnlein et al. 2014; Walsh et al. 2009). 2M2B was used throughout this study.

Enzyme screening

Six commercial lipases, including Novozym 435 (Candida antarctica lipase B, CALB) and Lipozyme TLIM (Thermomyces lanuginosus lipase, TLL) from Novozymes and four from Leveking (PEL, RCL, AOL, and ANL), were screened for their activities in catalyzing the synthesis of glucose laurate in 2M2B by comparing the conversion obtained with the addition of 0.5 g of each enzyme (Fig. 2). Clearly, Nozozym 435 yielded the highest conversion, followed by Lipozyme TLIM, AOL, and ANL, whereas a negligible amount of the sugar ester product was produced by RCL and PEL. Although Novozym 435 has been the most popular enzyme used in sugar ester synthesis and a few other lipases have also been applied for this application (Ye and Hayes 2014; Gumel et al. 2011; Kobayashi 2011; Ikeda and Klibanov 1993; Ferrer et al. 2000; Walsh et al. 2009; H-Kittikun et al. 2012), our experiment has offered two more lipases (AOL and ANL) that are considerably active in catalyzing SFAE synthesis. AOL was used as the catalyst for the subsequent reactions.

AOL-catalyzed synthetic reaction and its affecting factors

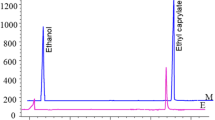

Catalyzed by the lipase AOL, the glucose laurate product (GL) was progressively produced via transesterification of glucose with vinyl laurate (VL), while a by-product, lauric acid (LA), was also generated (Fig. 3). The free lauric acid can be produced from the hydrolysis of both the co-substrate (vinyl laurate) and the product (glucose laurate), as long as there is a trace amount of water present in the reaction system. Lipases are carboxyl-esterases catalyzing hydrolysis or transesterification of esters, following a mechanism similar to the well-established acyl-enzyme mechanism for serine proteases (Reis et al. 2009). During the reaction course, water can compete with glucose for the acyl-enzyme intermediate to generate the free fatty acid. Therefore, the total amount of the three components (GL, VL, and LA) remained fairly constant as the reaction went on (Fig. 3), simply because of the decrease in the amount of the reactant, vinyl laurate (VL), which was accompanied by an increase in the formation of both the product, glucose laurate (GL) and the co-product, lauric acid (LA). Because the formation of glucose laurate reached a plateau after reaction for 5 h, for later experiments conversions obtained at 5 h were reported.

Variation of the concentrations of vinyl laurate (VL), lauric acid (LA), and glucose laurate (GL) during the reaction course. Reaction conditions: 0.27 g glucose (equivalent to 0.3 mol−1 of the reaction system), 0.3 M vinyl laurate, 5.0 ml 2M2B, 1.0 g molecular sieves, 0.3 g enzyme (AOL), 300 rpm, 40 °C

As shown in Fig. 4a, an increase in water content in the reaction system resulted in a decrease in the formation of glucose laurate. As mentioned above, water can trigger a hydrolysis of both the co-substrate (VL) and the product (GL), thus leading to a lower conversion. In nonaqueous media, an enzyme normally requires an essential amount of water for its activation; but too much water may be harmful to the enzyme leading to its aggregation and eventually to its inactivation (Liu et al. 1991). Therefore, it is necessary to keep the water level in the reaction system as low as possible. Adding molecular sieves has been proven to be a convenient way to remove the water that is present in the reaction system or the water that is produced from the reverse hydrolytic reaction, and both the solvent and the reactants have to be thoroughly dried prior to the reaction.

Effect of water content (a), enzyme amount (b), reaction temperature (c) and substrate concentrations (d and e) on production of glucose laurate. The basic reaction conditions were the same as for Fig. 2, but for each experiment, one condition was altered while all others were kept unchanged

The impact of enzyme amount on the glucose laurate synthesis has also been examined (Fig. 4b). The conversion was raised first and then declined as the enzyme amount increased with an optimum obtained at 0.4 g. Part of the reasons for the later decline may be related to the hydrolysis of the product as mentioned above. Additionally, too high a concentration of the immobilized enzyme makes the mixing of the reaction slurry difficult. Taking the enzyme cost into consideration, using excessive enzyme is counterproductive. In this study, use of 0.4 g of the enzyme in the 5 ml reaction system is recommended.

Other factors affecting the enzymatic reaction include the reaction temperature and substrate concentrations. A range of temperatures (40–80 °C) has been tested, and the optimal reaction temperature was found to be 60 °C (Fig. 4c). In terms of substrate concentrations, when the concentration of vinyl laurate was fixed at 0.3 M (totally dissolved) while the amount of glucose varied in a range of 0–0.4 mol−1 of the reaction system (most of it was initially undissolved and unreacted), the formation of glucose laurate increased gradually, accompanied by a decrease in the conversion (Fig. 4d). The reduction in conversion with an increase in the applied glucose amount is not surprising, for the reported conversion here was calculated based on the amount of glucose that was applied, while most of this added glucose was initially undissolved and unreacted. Applying the sugar in solid state is favorable for the reaction because its suspended particles continuously replenish the dissolved pool of the substrate as it is consumed by the reaction, thus pushing the reaction forward. On the other hand, when the glucose input was fixed at 0.3 mol−1 of the reaction system while vinyl laurate was added varying in the range of 0–1.2 M, an optimal conversion was obtained at a VL concentration of 0.6 M (Fig. 4e).

The above single-factor experiments suggested the optimum for each reaction condition: reaction temperature at 60 °C, 400 mg enzyme, 2:1 M ratio for VL/Glc (with 0.3 mol of Glc per liter of the reaction system) in 5.0 ml dried 2M2B. After a reaction was conducted under these conditions for 5 h, a conversion of 50.9 % was obtained, which is obviously improved as compared to those obtained previously.

Optimization through RSM

Based on the above preliminary single-factor results, a response surface methodology (RSM) with a three-factor-three-level Box-Behnken design (BBD) was employed for modeling and optimization of the enzymatic synthesis of glucose laurate. The three factors (i.e., enzyme amount, VL/Glc molar ratio and reaction temperature) and their varying levels are listed in Table 1. A total of 17 runs were carried out, among which five were at the central point. The conversion obtained at 5 h was taken as a response parameter for the model.

The conversions obtained by prediction from the model were linearly correlated with the experimentally obtained values with a slope of 0.9488 and an R 2-value of 0.9488, indicating that the model is able to fit the experimental data fairly well. The model F-value of 14.41 implies that the model is significant. The adequate precision of 13.142 indicates an adequate signal. No statistical evidence of multi-collinearity was found because the VIF (variance inflation factor) values calculated for all the terms included in the model were around 1.0. The conversion can then be characterized by the following polynomial equation:

where Y is the predicted conversion (%), while X1, X2, and X3 refer to enzyme amount (mg), VL/Glc molar ratio and reaction temperature (°C), respectively.

A 3D response surface with contour plots is depicted in Fig. 5. A maximal conversion of 63.13 % was predicted by the model with a set of reaction conditions suggested: 420 mg enzyme, 2.3:1 VL/Glc M ratio, 70 °C. Under these conditions, three tests were conducted and an average conversion of 64.54 % (±0.51 %) was obtained, which is reasonably close to the predicted value. This further confirms the validity and adequacy of the model.

The RSM-mediated optimization has significantly improved the conversion from 25.8 % (Fig. 2) to 64.5 %. Moreover, the productivity obtained in our optimized system is also much higher than others reported in literature (Ferrer et al. 2000, 2005; Ikeda and Klibanov 1993; Pöhnlein et al. 2014; Yan et al. 1999) (Table 2). It has to be noted, however, that the optimal reaction temperature may not have been reached within the range tested in this study (50–70 °C). It is therefore anticipated that further optimizing the reaction conditions, as well as introducing the reaction into ionic liquid systems (Lin et al. 2015; Yang and Huang 2012), may result in an even more significant improvement. It is worth mentioning that although AOL has shown to be a promising enzyme for SFAE synthesis in terms of excellent productivity, specific productivity, and shorter reaction time, the conversion obtained by this enzyme is relatively low. One possibility for this may be related to product inhibition, which is under further investigation in our laboratory.

References

Bezerra MA, Santelli RE, Oliveira EP, Villar LS, Escaleira LA (2008) Response surface methodology (RSM) as a tool for optimization in analytical chemistry. Talanta 76:965–977

Cao L, Bornscheuer UT, Schmid RD (1996) Lipase-catalyzed solid phase synthesis of sugar esters. Fett/Lipid 98:332-335

Chen Z-G, Zong M-H, Lou W-Y (2007) Advance in enzymatic synthesis of sugar ester in non-aqueous media. J Mol Catal B Enzym 21:90–95

Degn P, Zimmermann W (2001) Optimization of carbohydrate fatty acid ester synthesis in organic media by a lipase from Candida antarctica. Biotechnol Bioeng 74:483–491

Ferrer M, Cruces MA, Plou FJ, Bernabé M, Ballesteros A (2000) A simple procedure for the regioselective synthesis of fatty acid esters of maltose, leucrose, maltotriose and n–dodecyl maltosides. Tetrahedron 56:4053–4061

Ferrer M, Soliveri J, Plou FJ, López-Cortés N, Reyes-Duarte D, Christensen M, Copa-Patiño JL, Ballesteros A (2005) Synthesis of sugar esters in solvent mixtures by lipases from Thermomyces lanuginosus and Candida antarctica B, and their antimicrobial properties. Enzyme Microb Technol 36:391–398

Flores MV, Naraghi K, Engasser J-M, Halling PJ (2002) Influence of glucose solubility and dissolution rate on the kinetics of lipase catalyzed synthesis of glucose laurate in 2–methyl 2–butanol. Biotechnol Bioeng 78:815–821

Gumel AM, Annuar MSM, Heidelberg T, Chisti Y (2011) Lipase mediated synthesis of sugar fatty acid esters. Process Biochem 46:2079–2090

H-Kittikun A, Prasertsan P, Zimmermann W, Seesuriyachan P, Chaiyaso T (2012) Sugar ester synthesis by thermostable lipase from Streptomyces thermocarboxydus ME168. Appl Biochem Biotechnol 166:1969–1982

Ikeda I, Klibanov AM (1993) Lipase-catalyzed acylation of sugars solubilized in hydrophobic solvents by complexation. Biotechnol Bioeng 42:788–791

Kobayashi T (2011) Lipase-catalyzed syntheses of sugar esters in non-aqueous media. Biotechnol Lett 33:1911–1919

Laane C, Boeren S, Vos K, Veeger C (1987) Rules for optimization of biocatalysis in organic solvents. Biotechnol Bioeng 30:81–87

Lide DR (2001) CRC handbook of chemistry and physics, 82nd edn. CRC Press, Boca Raton

Lin X-S, Wen Q, Huang Z-L, Cai Y-Z, Halling PJ, Yang Z (2015) Impacts of ionic liquids on enzymatic synthesis of glucose laurate and optimization with superior productivity by response surface methodology. Process Biochem 50:1852–1858

Liu WR, Langer RL, Klibanov AM (1991) Moisture-induced aggregation of lyophilized proteins in the solid state. Biotechnol Bioeng 37:177–184

Miller GL (1959) Use of dinitrosalicylic acid reagent for determination of reducing sugar. Anal Chem 31:426–428

Pöhnlein M, Slomka C, Kukharenko O, Gärtner T, Wiemann LO, Sieber V, Syldatk C, Hausmann R (2014) Enzymatic synthesis of amino sugar fatty acid esters. Eur J Lipid Sci Technol 116:423–428

Puterka GJ, Farone W, Palmer T, Barrington A (2003) Structure-function relationships affecting the insecticidal and miticidal activity of sugar esters. J Econ Entomol 96:636–644

Reichardt C (1994) Solvatochromic dyes as solvent polarity indicators. Chem Rev 94:2319–2358

Reis P, Holmberg K, Watzke H, Leser ME, Miller R (2009) Lipases at interfaces: a review. Adv Colloid Interf Sci 147–148:237–250

Walsh MK, Bombyk RA, Wagh A, Bingham A, Berreau LM (2009) Synthesis of lactose monolaurate as influenced by various lipases and solvents. J Mol Catal B Enzym 60:171–177

Yan Y, Bornscheuer UT, Cao L, Schmid RD (1999) Lipase-catalyzed solid-phase synthesis of sugar fatty acid esters Removal of byproducts by azeotropic distillation. Enz Microb Technol 25:725–728

Yang Z, Huang Z-L (2012) Enzymatic synthesis of sugar fatty acid esters in ionic liquids. Catal Sci Technol 2:1767–1777

Ye R, Hayes DG (2014) Recent progress for lipase-catalysed synthesis of sugar fatty acid esters. J Oil Palm Res 26:355–365

Authors’ contributions

XL conceived of the study and carried out the RSM design. KZ assisted in data analysis and supervised the whole experiment. QZ and KX assisted in experimentation. PJH assisted in result discussion and draft revision. ZY was responsible for draft preparation and submission. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant number 21276159).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Lin, XS., Zhao, KH., Zhou, QL. et al. Aspergillus oryzae lipase-catalyzed synthesis of glucose laurate with excellent productivity. Bioresour. Bioprocess. 3, 2 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40643-015-0080-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40643-015-0080-6