Abstract

Purpose

Over the past 40 years, advances in the development of anchors and sutures have contributed to the improvement in surgical outcomes for treatment of shoulder instability. Important choices in surgery when treating instability include the use of knotless versus knotted suture anchors, and bony versus soft tissue reconstruction techniques.

Methods

A literature review was conducted to evaluate the history of instability of the shoulder and the results of specific fixation techniques including bony and soft tissue reconstructions as well as knotted and knotless suture anchors.

Results

As knotless suture anchors have continued to grow in popularity since their development in 2001, many studies have compared this newer technique to that of the standard knotted suture anchors. In general, these studies have demonstrated no difference in patient-reported outcome measures between the two options. Additionally, the choice of bony versus soft tissue reconstructions is patient specific as it depends on the specific pathology or combination of injuries.

Conclusion

In each surgery performed for shoulder instability, it is vitally important that we try to restore normal anatomy. The normal anatomy is best established by knotted mattress sutures. However, loop laxity and tear through by the sutures in the capsule can eliminate this restoration, increasing risk of failure. Knotless anchors may allow better soft tissue fixation of the labrum and capsule to the glenoid, but without complete restoration of normal anatomy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Historically, shoulder instability was addressed surgically with open procedures utilizing drill holes and silk sutures [25]. Over the past 40 years, advances in the development of anchors and sutures have contributed to the ease of surgery and improved outcomes. This opinion article discusses the use of varied fixation devices in the management of shoulder instability.

History of anterior instability

The most common direction of glenohumeral instability is anterior which makes up greater than 90% of all dislocations [14]. Anterior glenohumeral instability is usually the result of a traumatic injury, and will produce a variety of lesions, including labral and capsule avulsion defects, ligamentous tearing or increased laxity, and glenoid or humeral bone loss [2]. Prior to Perthes and then to Bankart in 1923, recurrent dislocation of the shoulder joint had been attributed to abnormal laxity of the capsule and weakness of the shoulder muscles [4]. However, in his 1923 article Bankart famously described a defect in the anteroinferior glenoid labrum and inferior glenohumeral ligament as a potential cause of recurrent anterior dislocation [4]. Since the introduction of this concept, a multitude of soft tissue and bony procedures have been described for the treatment of anterior glenohumeral instability [14].

Bony versus soft tissue reconstructions

Bankart described a repair of the lesion utilizing silk suture in a subscapularis tenotomizing approach [4]. In the 1940s, soft tissue transfers were popularized for the treatment of this condition. A procedure described by Gallie and LeMesurier in 1948 utilized a strip of facia lata passed through drill holes in the glenoid, humerus, and coracoid process to reconstruct the deficient structures [15, 25]. Another technique described by Magnuson and Stack in 1943 involves transferring the subscapularis attachment from the lesser tuberosity to the greater tuberosity to increase tension across the anteroinferior joint adding a suspensory element on the humeral head [25, 28]. The Putti-Platt procedure described in 1948 involved dividing the subscapularis tendon and capsule longitudinally and shortening these structures by securing the medial limb to the anterior glenoid and the lateral limb over the top of it [25, 30]. However, both the Magnuson-Slack procedure and the Putti-Platt procedure were associated with decreased external rotation and excessive tightening of the capsule which resulted in progression of glenohumeral arthritis and have since fallen out of favor [19, 25, 27].

Bony defects in the glenoid and/or humerus can also be significant contributors to anterior instability and risk factors for failure of soft tissue repair [8]. A commonly described lesion is the “bony Bankart” which is a detachment of the glenohumeral labral complex with an associated anterior glenoid rim fracture [31]. Humeral head bony defects can also contribute to anterior instability. The typical defect is known as a “Hill-Sachs” lesion which is a compression fracture at the posterolateral portion of the humeral head [21]. The landmark paper by Burkhart and DeBeer revolutionized the assessment of the unstable shoulder, making bone loss evaluation critical in the decision-making process [8]. Itoi, Digiacomo and others developed the concept of the glenoid track, helping us understand the contribution of the defects of both the humerus and glenoid bone to shoulder stability [13]. Numerous treatments have been described to address these associated bony defects. In 1954, Latarjet, unable to perform a Trillat procedure, adjusted and developed fixing the osteotomized coracoid process to augment the glenoid [23]. A similar procedure, described by Helfet and attributed to Bristow, used a single screw to place the coracoid “on end” to increase shoulder stability [20]. In the Latarjet procedure, the transferred coracoid extends the anterior aspect of the glenoid rim thus acting as a bony block [23]. In both the Latarjet and the Birstow procedures, the attached coracobrachialis acts as a sling to increase soft tissue restraints to anterior subluxation. In addition, in both techniques the transferred bone and soft tissue increase the tension on the lower subscapularis, increasing stability [1]. However, the Latarjet and the Bristow procedure may be associated with an increased complication rate as compared to soft tissue repair and mild loss of external rotation [16]. Several treatments of the Hill-Sachs lesion have been described including osteochondral allografts, rotational osteotomies, humeral head resurfacing, and shoulder arthroplasty [3, 11, 17, 40].

In terms of Hill-Sachs lesions, historically the determining factors in whether lesion was surgically addressed was the size and whether it “engages” or not [8]. However, in 2007 Yamamoto et al. introduced the concept of the “glenoid track” and demonstrated that if the Hill-Sachs lesion has a risk of engagement and dislocation if it extends over the medial margin of the glenoid track which can be determined by 3D computed tomography [42]. If this is the case, standard stabilization procedures such as the Bankart repair are unlikely to succeed in isolation [42]. Treatment of Hill-Sachs lesions often involves glenoid bone augmentation such as Latarjet or iliac crest grafting [9, 32]. This prevents engagement of the lesion by lengthening the articular arc of the glenoid [9]. Additional procedures to directly address the Hill-Sachs lesion include remplissage, disimpaction, resurfacing, or arthroplasty. These are typically indicated for Hill-Sachs lesions without concomitant glenoid bone loss [32].

Knotted versus knotless anchors

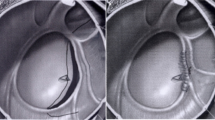

The initial attempts at arthroscopic Bankart repair involved the use of trans-glenoid drilling, an arthroscopic modification of the Viek technique, as described separately by Caspari, Savoie, and Morgan [10, 29, 34]. The development of the Mitek anchor ushered in the era of suture anchor fixation of the glenoid, avoiding bone tunnels and transglenoid fixation. Anchor development has continued since that time, with metal giving way to plastic then to absorbable and now all suture anchors [39]. The initial anchor sutures were ethibond and quite prone to breakage during attempted knot tying [6]. The development of fiberwire high tensile strength suture was a giant step forward in obtaining more adequate arthroscopic fixation. Secure knot tying has remained elusive for some surgeons, leading to the development of devices that eliminate knot tying due to studies that have shown that the outcome of the repair could be influenced by the knot security of the suture anchor, as well as injuring cartilage surfaces of the glenohumeral joint from the knots [35] (Fig. 1). Additionally, Thal et al. describes that, as arthroscopic repair has become widely used, the technique of knot tying is still inconsistent, yielding lower quality suture knots [37].

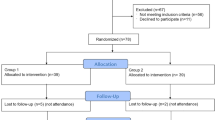

In 1997, Barber et al. restated the knot tying results posed a significant obstacle in arthroscopic surgery [5]. With the inconsistencies in knotted sutures and outcomes in arthroscopic repairs of shoulder instability, new operative techniques emerged to help eliminate or reduce these problems. In 2001, Thal published the first article using knotless suture anchors [38]. These were described to have a short loop of suture secured to the end of the anchor, with a channel, located at the tip of the anchor, functioning to capture the loop of suture [38]. Thal also demonstrated that this new surgical technique provided increased suture strength compared with standard knotted suture anchors [38]. As such, the utilization of knotless sutures proposed a novel method to avoiding the complications and concerns regarding technique and outcome of knotted suture anchors (Fig. 2).

Biomechanical cadaveric studies have recently demonstrated that knotless suture anchors showed similar or greater biomechanical strength to knotted suture anchors [22, 24]. Wu et al. demonstrated that knotless suture anchors had similar rates of re-dislocation and revision surgery, but lower rates or recurrent subluxation, compared to knotted suture anchors in a retrospective study of 102 patients [41]. Additionally, Bents et al. conducted a 1-year follow-up study of 226 repairs using either knotless or knotted suture anchors and demonstrated that no difference in patient-reported outcome measures were found between the cohorts, but that operative time was shorter for patients who received knotless suture anchors [7]. This is consistent with other studies also demonstrating that no differences in activities of daily living or patient reported outcomes are seen between the two options [33, 43]. As such, both the knotless sutures and traditional knotted suture anchors are still currently used in arthroscopic repairs for anterior shoulder instability.

Where are we going?

In each instability surgery it is vitally important that we try to restore normal anatomy. The labrum is not a bumper, but sits on the face of the glenoid, providing a connection of the more elastic capsule to the more rigid bone. In addition, proper restoration of the labrum re-established the “suction cup” effect which also increases stability [26]. The normal anatomy is best established by knotted mattress sutures [18]. However, loop laxity and tear through by the sutures in the capsule can eliminate this restoration, increasing risk of failure. Changing from mattress to simple sutures, but with knot tying will decrease the suture pull through risk but does not address the loop laxity issue. Knotless anchors, now with tape, may allow better soft tissue fixation of the labrum and capsule to the glenoid, but without complete restoration of normal anatomy [12]. The is also the risk of the exposed suture “rubbing” on the articular cartilage, increasing the risk of arthritis [36].

Authors recommendations

In the more critical 6 o’clock position we believe double loaded anchors with mattress sutures are needed to begin the capsular shift and restore normal labral anatomy. Similarly, below the equator of the joint we believe knotless anchors provide better anatomical support, as long as the surgeon is comfortable with secure knot fixation techniques. Above 3 o’clock position it is our opinion that knotless anchors seem to provide better fixation and less risk to articular cartilage than in the more inferior position.

References

Allain J, Goutallier D, Glorion C (1998) Long-term results of the Latarjet procedure for the treatment of anterior instability of the shoulder. J Bone Joint Surg Am 80:841–852. https://doi.org/10.2106/00004623-199806000-00008

Apostolakos JM, Wright-Chisem J, Gulotta LV, Taylor SA, Dines JS (2021) Anterior glenohumeral instability: Current review with technical pearls and pitfalls of arthroscopic soft-tissue stabilization. World J Orthop 12:1–13. https://doi.org/10.5312/wjo.v12.i1.1

Armitage MS, Faber KJ, Drosdowech DS, Litchfield RB, Athwal GS (2010) Humeral head bone defects: remplissage, allograft, and arthroplasty. Orthop Clin North Am 41:417–425. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ocl.2010.03.004

Bankart AS (1923) Recurrent or habitual dislocation of the shoulder-joint. Br Med J 2:1132–1133. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.2.3285.1132

Barber FA, Feder SM, Burkhart SS, Ahrens J (1997) The relationship of suture anchor failure and bone density to proximal humerus location: a cadaveric study. Arthroscopy 13:340–345. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0749-8063(97)90031-1

Barber FA, Herbert MA, Beavis RC (2009) Cyclic load and failure behavior of arthroscopic knots and high strength sutures. Arthroscopy 25:192–199. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arthro.2008.09.010

Bents EJ, Brady PC, Adams CR, Tokish JM, Higgins LD, Denard PJ (2017) Patient-Reported Outcomes of Knotted and Knotless Glenohumeral Labral Repairs Are Equivalent. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ) 46:279–283

Burkhart SS, De Beer JF (2000) Traumatic glenohumeral bone defects and their relationship to failure of arthroscopic Bankart repairs: significance of the inverted-pear glenoid and the humeral engaging Hill-Sachs lesion. Arthroscopy 16:677–694. https://doi.org/10.1053/jars.2000.17715

Burkhart SS, De Beer JF, Barth JRH, Cresswell T, Criswell T, Roberts C, Richards DP (2007) Results of modified Latarjet reconstruction in patients with anteroinferior instability and significant bone loss. Arthroscopy 23:1033–1041. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arthro.2007.08.009

Caspari RB (1988) Arthroscopic reconstruction for anterior shoulder instability. Tech Orthop 3:59–66

Chapovsky F, Kelly JD (2005) Osteochondral allograft transplantation for treatment of glenohumeral instability. Arthroscopy 21:1007. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arthro.2005.04.005

Denard PJ, Adams CR, Fischer NC, Piepenbrink M, Wijdicks CA (2018) Knotless Fixation Is Stronger and Less Variable Than Knotted Constructs in Securing a Suture Loop. Orthop J Sports Med 6:2325967118774000. https://doi.org/10.1177/2325967118774000

Di Giacomo G, Itoi E, Burkhart SS (2014) Evolving concept of bipolar bone loss and the Hill-Sachs lesion: from “engaging/non-engaging” lesion to “on-track/off-track” lesion. Arthroscopy 30:90–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arthro.2013.10.004

Dumont GD, Russell RD, Robertson WJ (2011) Anterior shoulder instability: a review of pathoanatomy, diagnosis and treatment. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med 4:200–207. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12178-011-9092-9

Gallie WE, Le Mesurier AB (1948) Recurring dislocation of the shoulder. J Bone Joint Surg Br 30B:9–18

Griesser MJ, Harris JD, McCoy BW, Hussain WM, Jones MH, Bishop JY, Miniaci A (2013) Complications and re-operations after Bristow-Latarjet shoulder stabilization: a systematic review. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 22:286–292. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jse.2012.09.009

Grondin P, Leith J (2009) Case series: Combined large Hill-Sachs and bony Bankart lesions treated by Latarjet and partial humeral head resurfacing: a report of 2 cases. Can J Surg 52:249–254

Hagstrom LS, Marzo JM (2013) Simple versus horizontal suture anchor repair of Bankart lesions: which better restores labral anatomy? Arthroscopy 29:325–329. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arthro.2012.08.025

Hawkins RJ, Angelo RL (1990) Glenohumeral osteoarthrosis. A late complication of the Putti-Platt repair. J Bone Joint Surg Am 72:1193–1197

Helfet AJ (1958) Coracoid transplantation for recurring dislocation of the shoulder. J Bone Joint Surg Br 40-B:198–202. https://doi.org/10.1302/0301-620X.40B2.198

Hill HA, Sachs MD (1940) The Grooved Defect of the Humeral Head. Radiology 35:690–700. https://doi.org/10.1148/35.6.690

Lacheta L, Brady A, Rosenberg SI, Dornan GJ, Dekker TJ, Anderson N, Altintas B, Krob JJ, Millett PJ (2020) Biomechanical Evaluation of Knotless and Knotted All-Suture Anchor Repair Constructs in 4 Bankart Repair Configurations. Arthroscopy 36:1523–1532. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arthro.2020.01.046

Latarjet M (1954) Treatment of recurrent dislocation of the shoulder. Lyon Chir 49:994–997

Leedle BP, Miller MD (2005) Pullout strength of knotless suture anchors. Arthroscopy 21:81–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arthro.2004.08.011

Levy DM, Cole BJ, Bach BR (2016) History of surgical intervention of anterior shoulder instability. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 25:e139-150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jse.2016.01.019

Lippitt S, Matsen F (1993) Mechanisms of glenohumeral joint stability. Clin Orthop Relat Res (291):20–28

Lusardi DA, Wirth MA, Wurtz D, Rockwood CA (1993) Loss of external rotation following anterior capsulorrhaphy of the shoulder. J Bone Joint Surg Am 75:1185–1192. https://doi.org/10.2106/00004623-199308000-00008

Magnuson PB, Stack JK (1991) Recurrent dislocation of the shoulder. 1943. Clin Orthop Relat Res 4–8; discussion 2–3. https://doi.org/10.1097/00003086-199108000-00002

Morgan CD (1991) Arthroscopic transglenoid Bankart suture repair. Oper Tech Orthop 1:171–179. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1048-6666(05)80028-X

Osmond-Clarke H (1948) Habitual dislocation of the shoulder; the Putti-Platt operation. J Bone Joint Surg Br 30B:19–25

Porcellini G, Campi F, Paladini P (2002) Arthroscopic approach to acute bony Bankart lesion. Arthroscopy 18:764–769. https://doi.org/10.1053/jars.2002.35266

Provencher MT, Frank RM, Leclere LE, Metzger PD, Ryu JJ, Bernhardson A, Romeo AA (2012) The Hill-Sachs lesion: diagnosis, classification, and management. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 20:242–252. https://doi.org/10.5435/JAAOS-20-04-242

Reinig Y, Welsch F, Hoffmann R, Müller D, Gramlich S, Fischer S, Schüttler KF, Zimmermann E, Stein T (2019) Assessments of activities of daily living after arthroscopic SLAP repair with knot-tying versus knotless suture anchors. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 139:981–990. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00402-019-03151-5

Savoie FH, Miller CD, Field LD (1997) Arthroscopic reconstruction of traumatic anterior instability of the shoulder: the Caspari technique. Arthroscopy 13:201–209. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0749-8063(97)90155-9

Shim JW, Jung TW, Kim IS, Yoo JC (2021) Knot-Tying versus Knotless Suture Anchors for Arthroscopic Bankart Repair: A Comparative Study. Yonsei Med J 62:743–749. https://doi.org/10.3349/ymj.2021.62.8.743

Solomon DJ, Navaie M, Stedje-Larsen ET, Smith JC, Provencher MT (2009) Glenohumeral chondrolysis after arthroscopy: a systematic review of potential contributors and causal pathways. Arthroscopy 25:1329–1342. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arthro.2009.06.001

Thal R (2001) Knotless suture anchor: arthroscopic bankart repair without tying knots. Clin Orthop Relat Res 42–51

Thal R (2001) A knotless suture anchor. Design, function, and biomechanical testing. Am J Sports Med 29:646–649. https://doi.org/10.1177/03635465010290051901

Visscher LE, Jeffery C, Gilmour T, Anderson L, Couzens G (2019) The history of suture anchors in orthopaedic surgery. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon) 61:70–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2018.11.008

Weber BG, Simpson LA, Hardegger F (1984) Rotational humeral osteotomy for recurrent anterior dislocation of the shoulder associated with a large Hill-Sachs lesion. J Bone Joint Surg Am 66:1443–1450

Wu IT, Desai VS, Mangold DR, Camp CL, Barlow JD, Sanchez-Sotelo J, Dahm DL, Krych AJ (2021) Comparable clinical outcomes using knotless and knot-tying anchors for arthroscopic capsulolabral repair in recurrent anterior glenohumeral instability at mean 5-year follow-up. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 29:2077–2084. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-020-06057-7

Yamamoto N, Itoi E, Abe H, Minagawa H, Seki N, Shimada Y, Okada K (2007) Contact between the glenoid and the humeral head in abduction, external rotation, and horizontal extension: a new concept of glenoid track. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 16:649–656. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jse.2006.12.012

Yang HJ, Yoon K, Jin H, Song HS (2016) Clinical outcome of arthroscopic SLAP repair: conventional vertical knot versus knotless horizontal mattress sutures. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 24:464–469. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-014-3449-8

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Collins, L.K., Cole, M.W., Savoie, F.H. et al. Fixation devices for anterior shoulder instability. J EXP ORTOP 10, 51 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40634-023-00610-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40634-023-00610-2