Abstract

Background

While most anatomic TSA stems allow some intra-operative adjustments, the default configuration assumes that head offset is directly proportional to stem diameter. Some authors reported that humeral head diameter is proportional to intra-medullary canal width and humeral head offset, but none investigated the direct relationship between head offset and endosteal measurements. The purpose of the study was to determine whether global humeral head offset is proportional to intramedullary canal width at the distal metaphysis and proximal diaphysis.

Methods

We analyzed 100 Computed Tomography shoulder scans of patients aged 59.1 ± 20.5 with no signs of gleno-humeral arthritis nor humeral dysplasia. The width of the intramedullary diaphyseal canal was determined at four transverse sections 65, 70, 100 and 105 mm below the head center. The inter-observer agreement was excellent for intramedullary canal width (ICC = 0.96), head diameter (ICC = 0.97) and global head offset (ICC = 0.85). Correlations were analysed using Pearson’s coefficients and multivariable regressions were performed to determine associations between head offset and five independent variables (gender, age, intramedullary canal width, head diameter).

Results

Global head offset was negatively correlated with head diameter (r = − 0.31, p = 0.002), but not correlated with intramedullary canal width (r = − 0.11, p = 0.282). Multivariable regression confirmed that global head offset was independently associated with head diameter (beta = − 0.15, p = 0.005), but not with intramedullary canal width (beta = 0.06, p = 0.431).

Conclusions

The present study revealed that humeral offset is not correlated with intramedullary canal width. Implant manufacturers and shoulder surgeons should be aware of the subtle morphologic features, to enhance humeral stem design and restore native anatomy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Success of total shoulder arthroplasty (TSA) requires accurate restoration of anatomy (Godeneche et al., 2002; Irlenbusch et al., 2011; Pearl, 2005; Pearl et al., 2009; Wirth et al., 2007), as even small discrepancies between native and prosthetic geometry could trigger pain and compromise function (Kadum et al., 2016; Pearl et al., 2002; Pearl & Volk, 1996). For these reasons, most commercially-available anatomic TSA stems allow some intra-operative adjustments of humeral head offset – the distance between the head center and the diaphyseal axis – using ‘telephone dial’ or linear peg-hole configurations (Boileau & Walch, 1997; Irlenbusch et al., 2011; Pearl et al., 2009).

Numerous studies investigated the anatomy of the proximal humerus, first using 3D reconstructions of fresh or dry cadaver bones (Boileau & Walch, 1997; Hertel et al., 2002; McPherson et al., 1997; Pearl & Volk, 1996; Robertson et al., 2000; Roche et al., 2006), and more recently using X-rays (Boileau & Walch, 1997; Hertel et al., 2002; McPherson et al., 1997; Pearl & Volk, 1996; Robertson et al., 2000; Roche et al., 2006) or computed tomography (CT) scans (Aroonjarattham et al., 2009; Bockmann et al., 2016; Boileau et al., 2008; Deladerriere et al., 2012; Jia et al., 2016; Johnson et al., 2013; Kadum et al., 2016; Matsumura et al., 2014; Matsumura et al., 2016; Saka et al., 2015; Vlachopoulos et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2016). Some authors reported that humeral head diameter is proportional to both intra- and extra-medullary humeral diameters (McPherson et al., 1997) as well as to humeral head offset (Pearl & Volk, 1996), but none investigated the direct relationship between head offset and endosteal measurements.

While some anatomic humeral components are designed with head offset proportional to stem size, others are designed with constant head offset regardless of stem size (Table 1). To the authors’ knowledge, there are no anatomic studies that investigated the correlation between native head offset and intramedullary canal width. The purpose of this study was therefore to determine the relationship between head offset and intramedullary canal width in the proximal humerus. The hypothesis was that native head offset is not correlated with intramedullary canal width.

Methods

From their databases of pre-existing shoulder CT images, the authors selected 100 scans that had sufficient resolution (slice thickness 0.5 mm, with a 64 slices CT scanner) and length (> 11 cm of proximal humeri), excluding shoulders with signs of: (i) osteoarthritis or rheumatoid arthritis, (ii) Hill Sachs lesions, (iii) humeral head necrosis or deformities, and (iv) mal-unions secondary to displaced humeral neck fractures. The cohort comprised 62 men and 38 women aged 59.1 ± 20.5 years (range, 18–96). The patients presented with fractures of the scapula or clavicle (45), rotator cuff tears (39), shoulder dislocation or instability with no signs of osseous damage at the proximal humerus or glenoid (9), tumor at the scapula or distal humerus (5), calcific tendinitis (1) and thoracic syndrome (1). All patients provided informed consent to use of their images and data for research and publishing purposes. As the study was performed using pre-existing CT scans, institutional review board (IRB) approval was not required.

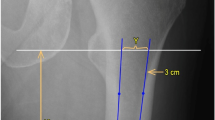

The Digital Imaging and Communication in Medicine (DICOM) files were processed using Osirix (Pixmeo SARL, Bernex, Switzerland) in standard resolution. Four series of 8 points were digitalised on endosteal transverse sections 65, 70, 100 and 105 mm below the head center (Fig. 1), to determine the width of the intramedullary diaphyseal canal, using the ‘cylinder of best fit’ method, and to establish the cranio-caudal (CC) axis. Three series of 8 points were also digitized on the surface of the humeral head (1 series per plane) to determine the humeral head diameter, using the ‘sphere of best fit’ method and to establish the coordinates of the head center. Because the CT scans did not include the elbow joint, it was not possible to establish the mediolateral (ML) axis using the coordinates of the humeral epicondyles. Instead, the coordinates of the centre of the proximal bicipital groove, at the level revealing its full depth, were used to approximate the humeral transepicondylar (TEA), by applying an external rotation of 60° to the line connecting the head center to the proximal bicipital groove (Fig. 2). The approximation was deduced from two recent studies: (i) Johnson et al. (Johnson et al., 2013), who reported the “proximal groove” to be at 60° of internal rotation relative to the humeral TEA; and (ii) Oh et al. (Oh et al., 2017), who found the bicipital groove to be at 60.6° of internal rotation relative to the TEA (“method 2” 30° between bicipital groove and reference line + 30.6° between reference line and TEA). The anterior and posterior boundaries of the anatomic neck were digitized using the limits of the subchondral bone on axial slices, 5–7 mm below the slice where the humeral head has it maximum diameter, and their perpendicular bisector defined the humeral neck axis, which was used to calculate head retroversion with respect to the estimated ML axis. The global head offset was determined by measuring the medial and posterior distances between the humeral head centre and the CC axis in the transverse plane (Fig. 3).

Determination of the humeral head center coordinates by digitizing 3 series of 8 points on the head surface (‘sphere of best fit’ method), and determination of the intra-medullary canal axis and width by digitizing 4 series of 8 points on transverse sections 65, 70, 100 and 105 mm below the head center (‘cylinder of best fit’ method)

Statistical analysis

The sample size necessary to test the hypothesis, that there is no correlation (− 0.24 < r < 0.24) between native head offset and intramedullary canal width, with alpha = 0.05 and beta = 0.80, was calculated a priori to be a minimum of 71 patients.

The authors selected 13 shoulders at random, for which all parameters were measured by a second observer, to calculate their inter-observer agreement. The intra-class correlation coefficients (ICC) were excellent for intramedullary canal width (ICC = 0.96; CI, 0.60–0.99), head diameter (ICC = 0.97; CI, 0.91–0.99) and global head offset (ICC = 0.85; CI, 0.58–0.95).

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the data. Shapiro–Wilk tests were used to assess the normality of distributions. For non-Gaussian quantitative data, differences between groups were evaluated using Wilcoxon rank-sum tests (Mann–Whitney U test). For continuous variables, correlations were analysed using Pearsons coefficients. Uni-variable and multivariable linear regressions were performed to determine associations between head offset and five independent variables (gender, age, intramedullary canal width, head diameter, and head retroversion). Both uni- and multi-varaible analyses were deemed necessary to identify potential confounding variables. Statistical analyses were performed using R version 3.3.3 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). P-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

The average intramedullary canal width was 14.5 ± 2.5 mm (range, 9.4–20.5), and the average head diameter was 44.9 ± 4.4 mm (range, 36.2–56.0), with a retroversion of 24.6° ± 19.2° (range, − 30.7°–59.8°) (Table 2). The mean global head offset was 5.9 ± 1.4 mm (range, 3.4–10.8), with a medial component of 5.1 ± 1.5 mm (range, 2.2–10.7) and a posterior component of 2.2 ± 1.6 mm (range, − 0.9 – 6.4). There were no significant differences in global offset between men and women (5.80 ± 1.45 vs 6.11 ± 1.31; p = 0.094).

Intramedullary canal width was positively correlated with head diameter (r = 0.63, CI = 0.50–0.74; p < 0.001). Global head offset was negatively correlated with head diameter (r = − 0.31, CI = − 0.48 – -0.13; p = 0.002), but not with intramedullary canal width (r = − 0.11; CI = − 0.30–0.09; p = 0.282), thus confirming the study hypothesis (Fig. 4). Medial head offset was negatively correlated with head diameter (r = − 0.28, CI = − 0.45– -0.09; p = 0.004), but not with intramedullary canal width (r = − 0.13; CI = − 0.32–0.07; p = 0.187). Posterior head offset was neither correlated with head diameter (r = − 0.11, CI = − 0.30–0.09; p = 0.298), nor with intramedullary canal width (r = − 0.05; CI = − 0.24–0.15; p = 0.645).

Uni-variable regression revealed that global head offset was significantly associated with head diameter (beta, − 0.10; CI, − 0.16 – -0.04; p = 0.001) and patient age (beta, 0.01; CI, 0.00–0.03; p = 0.033) but not with intramedullary canal width (beta, − 0.06; CI, − 0.17–0.05; p = 0.282) (Table 3). Multivariable regression confirmed that global head offset was independently associated with head diameter (beta, − 0.15; CI, − 0.26 – -0.04; p = 0.005), but not with intramedullary canal width (beta, 0.06; CI, − 0.09–0.20; p = 0.431), reaffirming the study hypothesis.

Discussion

The principal finding of our study was that there is no correlation between head offset and intramedullary canal width, thereby confirming our hypothesis. Accurate restoration of anatomy is a prerequisite for the success of TSA (Godeneche et al., 2002; Irlenbusch et al., 2011; Pearl, 2005; Pearl et al., 2009; Wirth et al., 2007). Many anatomic parameters, such as head offset and height, center of rotation, and neck-shaft angle, have been studied to improve the design of anatomic humeral stems (Aroonjarattham et al., 2009; Irlenbusch et al., 2011; Jeong et al., 2009; Kadum et al., 2016; McPherson et al., 1997; Pearl, 2005; Robertson et al., 2000; Roche et al., 2006). While landmark studies reported that humeral head diameter is proportional to intra-medullary canal width (McPherson et al., 1997) and head offset (Pearl & Volk, 1996), this study is the first to investigate the direct relationship between head offset and intramedullary canal width.

It is important to note that, as in numerous published studies, our anatomic parameters were measured on shoulders with normal or healthy bone morphology, whereas the findings are relevant to design prosthetic humeral stems for arthritic shoulders that feature substantial proximal deformations. We chose to study shoulders with normal or healthy bone morphology for two reasons: (i) in arthritic shoulders, subchondral damage to the humeral head often renders calculations of its diameter and centre difficult and inaccurate; and (ii) the goals of TSA are to replace damaged articular surfaces and restore adequate joint architecture, which is often deformed due to congenital or progressive pathologies in arthritic shoulders.

While shoulder arthroplasty was initially intended for elderly patients with low functional expectations, TSA is now performed in younger patients with greater functional demands, which renders reconstruction of native anatomy all the more essential. Modern TSA implants allow for some adjustments of humeral head offset (Irlenbusch et al., 2011; Wirth et al., 2007), but some default designs assume it to be directly proportional to stem diameter, such that larger stems are designed with greater head offsets (Table 1). Our multivariable analysis suggests that this assumption is incorrect, as global head offset was not associated with intramedullary canal width, even when considering the effects of age, gender, and head retroversion.

Our morphologic measurements are within the ranges reported in other published studies (Table 4): 43–51 mm for head diameter (Aroonjarattham et al., 2009; Hertel et al., 2002; Matsumura et al., 2016; Merolla et al., 2008), 16°–31° for head retroversion (Aroonjarattham et al., 2009; Boileau et al., 2008; Harrold & Wigderowitz, 2013; Hertel et al., 2002; Johnson et al., 2013; Matsumura et al., 2016; Oh et al., 2017; Roberts et al., 1991; Robertson et al., 2000), 7–15 mm for intramedullary canal width (Akpinar et al., 2003; McPherson et al., 1997; Murdoch et al., 2002), and 1–4 mm for posterior head offset (Aroonjarattham et al., 2009; Boileau et al., 2008; Hertel et al., 2002; Merolla et al., 2008; Robertson et al., 2000). The medial component of the global head offset was also within the range of 4–6 mm from CT studies (Aroonjarattham et al., 2009; Deladerriere et al., 2012), but below the range of 6–10 mm from X-ray studies (Boileau & Walch, 1997; Hertel et al., 2002; Merolla et al., 2008; Pearl & Volk, 1996; Robertson et al., 2000). This discrepancy is likely due to magnification and rotation in X-ray measurements, which tend to exaggerate the true medial offset. While Pearl et al. (Pearl & Volk, 1996) found the correlation between medial head offset and head diameter to be moderate and positive (r = 0.6), we found it to be weak and negative (r = − 0.28). These contradictory results might be explained by differences in measurement techniques, as Pearl et al. used cadaver bone x-rays, and referred to the reamed canal for the CC axis.

The limitations of this study include: (i) the inability to determine the transepicondylar axis to establish the frontal humeral plane and calculate true head retroversion, (ii) the digitization of endosteal transverse sections at fixed rather than proportional distances below the head center, which was not possible because the total heights of the humerus and of the patient were unknown, (iii) the population studied was Caucasian, and may not be representative of other ethnicities (Aroonjarattham et al., 2009; Matsumura et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2016), and (iv) the cohort did not comprise any arthritic joints which may have different morphologic characteristics. The main strengths of this study are the use of CT-scans which were demonstrated to be more accurate than X-rays in the assessment of morphology of the proximal humerus (Jia et al., 2016) and a precise measurement method validated by strong inter-observer repeatability.

Conclusions

The present study revealed that humeral offset is not correlated with intramedullary canal width. These findings are relevant to implant manufacturers and shoulder surgeons, who should be aware of the subtle morphologic features, to enhance humeral stem design and restore native anatomy.

Abbreviations

- CC:

-

Cranio-caudal

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- ICC:

-

Intra-class correlation coefficients

- ML:

-

MedioLateral

- TSA:

-

Total shoulder arthroplasty

References

Akpinar F, Aydinlioglu A, Tosun N, Dogan A, Tuncay I, Unal O (2003) A morphometric study on the humerus for intramedullary fixation. Tohoku J Exp Med 199(1):35–42

Aroonjarattham P, Jiamwatthanachai P, Mahaisavariya B, Kiatiwat T, Aroonjaratthammd K, Sitthiseripratip K (2009) Three-dimensional morphometric study of the Thai proximal humerus: cadaveric study. J Med Assoc Thail 92(9):1191–1197

Bockmann B, Soschynski S, Lechler P, Schwarting T, Debus F, Soca B, Ruchholtz S, Frink M (2016) The osseous morphology of nondegenerated shoulders shows no side-related differences in elderly patients: an analysis of 102 computed tomography scans. J Shoulder Elb Surg 25(8):1297–1302

Boileau P, Bicknell RT, Mazzoleni N, Walch G, Urien JP (2008) CT scan method accurately assesses humeral head retroversion. Clin Orthop Relat Res 466(3):661–669

Boileau P, Walch G (1997) The three-dimensional geometry of the proximal humerus. Implications for surgical technique and prosthetic design. J Bone Joint Surg Br 79(5):857–865

Deladerriere JY, Szymanski C, Vervoort T, Budzik JF, Maynou C (2012) Geometrical analysis results of 42 resurfacing shoulder prostheses: a CT scan study. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res 98(5):520–527

Godeneche A, Boileau P, Favard L, Le Huec JC, Levigne C, Nove-Josserand L, Walch G, Edwards TB (2002) Prosthetic replacement in the treatment of osteoarthritis of the shoulder: early results of 268 cases. J Shoulder Elb Surg 11(1):11–18

Harrold F, Wigderowitz C (2013) Humeral head arthroplasty and its ability to restore original humeral head geometry. J Shoulder Elb Surg 22(1):115–121

Hertel R, Knothe U, Ballmer FT (2002) Geometry of the proximal humerus and implications for prosthetic design. J Shoulder Elb Surg 11(4):331–338

Irlenbusch U, End S, Kilic M (2011) Differences in reconstruction of the anatomy with modern adjustable compared to second-generation shoulder prosthesis. Int Orthop 35(5):705–711

Jeong J, Bryan J, Iannotti JP (2009) Effect of a variable prosthetic neck-shaft angle and the surgical technique on replication of normal humeral anatomy. J Bone Joint Surg Am 91(8):1932–1941

Jia X, Chen Y, Qiang M, Zhang K, Li H, Jiang Y, Zhang Y (2016) Compared to X-ray, three-dimensional computed tomography measurement is a reproducible radiographic method for normal proximal humerus. J Orthop Surg Res 11(1):82

Johnson JW, Thostenson JD, Suva LJ, Hasan SA (2013) Relationship of bicipital groove rotation with humeral head retroversion: a three-dimensional computed tomographic analysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am 95(8):719–724

Kadum B, Wahlstrom P, Khoschnau S, Sjoden G, Sayed-Noor A (2016) Association of lateral humeral offset with functional outcome and geometric restoration in stemless total shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elb Surg 25(10):e285–e294

Matsumura N, Ogawa K, Kobayashi S, Oki S, Watanabe A, Ikegami H, Toyama Y (2014) Morphologic features of humeral head and glenoid version in the normal glenohumeral joint. J Shoulder Elb Surg 23(11):1724–1730

Matsumura N, Oki S, Ogawa K, Iwamoto T, Ochi K, Sato K, Nagura T (2016) Three-dimensional anthropometric analysis of the glenohumeral joint in a normal Japanese population. J Shoulder Elb Surg 25(3):493–501

McPherson EJ, Friedman RJ, An YH, Chokesi R, Dooley RL (1997) Anthropometric study of normal glenohumeral relationships. J Shoulder Elb Surg 6(2):105–112

Merolla G, Di Pietto F, Romano S, Paladini P, Campi F, Porcellini G (2008) Radiographic analysis of shoulder anatomical arthroplasty. Eur J Radiol 68(1):159–169

Murdoch AH, Mathias KJ, Smith FW (2002) Measurement of the bony anatomy of the humerus using magnetic resonance imaging. Proc Inst Mech Eng H 216(1):31–35

Oh JH, Kim W, Cayetano AA Jr (2017) Measurement methods for humeral retroversion using two-dimensional computed tomography scans: which is most concordant with the standard method? Clin Orthop Surg 9(2):223–231

Pearl ML (2005) Proximal humeral anatomy in shoulder arthroplasty: implications for prosthetic design and surgical technique. J shoulder elbow Surg 14(1 Suppl S):99s–104s

Pearl ML, Kurutz S, Postacchini R (2009) Geometric variables in anatomic replacement of the proximal humerus: how much prosthetic geometry is necessary? J Shoulder Elb Surg 18(3):366–370

Pearl ML, Kurutz S, Robertson DD, Yamaguchi K (2002) Geometric analysis of selected press fit prosthetic systems for proximal humeral replacement. J Orthop Res 20(2):192–197

Pearl ML, Volk AG (1996) Coronal plane geometry of the proximal humerus relevant to prosthetic arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elb Surg 5(4):320–326

Roberts SN, Foley AP, Swallow HM, Wallace WA, Coughlan DP (1991) The geometry of the humeral head and the design of prostheses. J Bone Joint Surg Br 73(4):647–650

Robertson DD, Yuan J, Bigliani LU, Flatow EL, Yamaguchi K (2000) Three-dimensional analysis of the proximal part of the humerus: relevance to arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am 82-a(11):1594–1602

Roche C, Angibaud L, Flurin PH, Wright T, Fulkerson E, Zuckerman J (2006) Anatomic validation of an "anatomic" shoulder system. Bull Hosp Jt Dis 63(3–4):93–97

Saka M, Yamauchi H, Yoshioka T, Hamada H, Gamada K (2015) Conventional humeral retroversion measurements using computed tomography slices or ultrasound images are not correlated with the 3-dimensional humeral retroversion angle. Orthop J Sports Med 3(3):2325967115573701

Vlachopoulos L, Dunner C, Gass T, Graf M, Goksel O, Gerber C, Szekely G, Furnstahl P (2016) Computer algorithms for three-dimensional measurement of humeral anatomy: analysis of 140 paired humeri. J Shoulder Elb Surg 25(2):e38–e48

Wirth MA, Ondrla J, Southworth C, Kaar K, Anderson BC, Rockwood CA 3rd (2007) Replicating proximal humeral articular geometry with a third-generation implant: a radiographic study in cadaveric shoulders. J Shoulder Elb Surg 16(3 Suppl):S111–S116

Zhang Q, Shi LL, Ravella KC, Koh JL, Wang S, Liu C, Li G, Wang J (2016) Distinct proximal humeral geometry in Chinese population and clinical relevance. J Bone Joint Surg Am 98(24):2071–2081

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Aude Michelet and Mo Saffarini for their help in manuscript redaction.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

JB study design, data collection, literature review and manuscript writing. JG study design, and manuscript editing. AB study design, data collection and manuscript editing. ES study design and data collection. LG study design, data collection and manuscript editing. HB literature review, statistical analysis and manuscript writing. SFI study design, manuscript editing. AG study design, supervision and manuscript editing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Given that the study was performed using pre-existing CT scans, approval of the institutional review board was not required.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors did not receive any financial payments or other benefits from any commercial entity related to the subject of this article.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Barth, J., Garret, J., Boutsiadis, A. et al. Is global humeral head offset related to intramedullary canal width? A computer tomography morphometric study. J EXP ORTOP 5, 35 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40634-018-0148-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40634-018-0148-2