Abstract

Background

Suicide is a major public health problem with immediate and long-term effects on individuals, families, and communities. In 2020 and 2021, stressors wrought by the COVID-19 pandemic, stay-at-home mandates, economic turmoil, social unrest, and growing inequality likely modified risk for self-harm. The coinciding surge in firearm purchasing may have increased risk for firearm suicide. In this study, we examined changes in counts and rates of suicide in California across sociodemographic groups during the first two years of the COVID-19 pandemic relative to prior years.

Methods

We used California-wide death data to summarize suicide and firearm suicide across race/ethnicity, age, education, gender, and urbanicity. We compared case counts and rates in 2020 and 2021 with 2017–2019 averages.

Results

Suicide decreased overall in 2020 (4123 deaths; 10.5 per 100,000) and 2021 (4104; 10.4 per 100,000), compared to pre-pandemic (4484; 11.4 per 100,000). The decrease in counts was driven largely by males, white, and middle-aged Californians. Conversely, Black Californians and young people (age 10 to 19) experienced increased burden and rates of suicide. Firearm suicide also decreased following the onset of the pandemic, but relatively less than overall suicide; as a result, the proportion of suicides that involved a firearm increased (from 36.1% pre-pandemic to 37.6% in 2020 and 38.1% in 2021). Females, people aged 20 to 29, and Black Californians had the largest increase in the likelihood of using a firearm in suicide following the onset of the pandemic. The proportion of suicides that involved a firearm in 2020 and 2021 decreased in rural areas compared to prior years, while there were modest increases in urban areas.

Conclusions

The COVID-19 pandemic and co-occurring stressors coincided with heterogeneous changes in risk of suicide across the California population. Marginalized racial groups and younger people experienced increased risk for suicide, particularly involving a firearm. Public health intervention and policy action are necessary to prevent fatal self-harm injuries and reduce related inequities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Suicide is significant public health problem and a leading cause of death in the United States (USA). From 2010 to 2020, more than 480,000 people nationally died by suicide, the majority by firearm suicide. Recent social, economic, and environmental stressors may have affected the burden of and disparities in suicide.

On March 19, 2020, California went under a stay-at-home order in response to the COVID-19 pandemic (Office of Governor Gavin Newsom 2020). Non-essential businesses, such as bars, fitness clubs, and some stores, were ordered to close, and residents were asked to “shelter-in-place” at home. Many people lost employment or had to leave jobs to caretake for children or family members. A high percentage of adults had trouble paying bills or rent due to the pandemic (Pew Research Center 2020), and most became more socially isolated (Abelson 2021). At the same time, hundreds of thousands experienced loss of a loved one to COVID-19 (Verdery et al. 2020).

Compounded with the pandemic and its repercussions were a variety of other co-occurring stressors in 2020 and 2021, including the widely publicized murder of George Floyd, subsequent protests and incidents of police brutality, political turmoil surrounding the 2020 presidential election, climate-change-fueled megafires, and collective grief and trauma resulting from these events (Silver et al. 2021; Bühler et al. 2022). Notably, not all groups were equally impacted. Marginalized communities and racialized groups bore the disproportionate burden of the social, health, and economic consequences of 2020 and 2021 (Wilson 2020) as a result of the ongoing legacy of structural racism in the USA, which has concentrated disadvantages (including poverty, under-funded schools, unemployment, over-policing and police violence, mass incarceration, and limited access to affordable healthcare, housing, and green spaces) among Black, Indigenous, and Hispanic communities (Bailey et al. 2017).

Financial difficulties, unemployment, social isolation, and trauma have all been linked to suicide and related risk factors (e.g., suicidality, depression) (Batty et al. 2018; Elbogen et al. 2020). One analysis found that in the years following the economic downturn from 2007 to 2009, an estimated 4750 more Americans died by suicide than projected (Reeves et al. 2012). A study of quarantined people during the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) outbreak in 2003 found that approximately one-third of individuals experienced symptoms of depression and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), with higher rates of PTSD symptoms associated with longer durations of quarantine (Hawryluck et al. 2004). Prior pandemics have also been linked to suicide: some research suggests that deaths by suicide increased overall during the 1918–1919 influenza pandemic in the USA (Wasserman 1992) and among older people aged 65 and above in Hong Kong during the SARS epidemic (Cheung et al. 2008).

Several studies have examined the link between the COVID-19 pandemic and suicide, but findings are mixed. One 2021 survey of adults in the USA found an association between COVID-19-related experiences (i.e., general distress, fear of infection, effects of social distancing policies) and increased suicidal ideation and nonfatal suicide attempts, with a substantial proportion of those reporting suicidal ideation explicitly attributing it to COVID-19 (Ammerman et al. 2021). Risk of self-harm has also been associated with high perceived stress due to COVID-19 (Caballero-Domínguez et al. 2022). However, a 2021 systematic review of time series analyses in Brazil, China, Ecuador, Mexico, Peru, Russian Federation, and Sri Lanka found no change in intentional self-harm during COVID-19 (Knipe et al. 2022). In the USA, two studies in California found no change in intentional drug-related overdoses (Kiang et al. 2022) or suicidal ingestions reported to the California Poison Control system (Ontiveros et al. 2021) following the pandemic. At the same time, there is evidence that—contrary to expectations—deaths by suicide decreased in Cook County, Illinois and in four Texas counties through July 31, 2020 (Pirkis et al. 2021). Differences between studies may stem in part from the populations under study. Importantly, analyses of aggregate trends may mask substantial heterogeneity in population subgroups, especially for subpopulations who comprise a minority of the overall population (Fox et al. 2022).

Beginning in 2020, firearm and ammunition purchasing in the USA far surpassed expected levels. Through July 2020, there were an estimated 4.3 million excess firearm purchases nationally (Schleimer et al. 2021) and, in California, approximately 110,000 people acquired a firearm and 390,000 purchased ammunition in response to the pandemic (Kravitz-Wirtz et al. 2021). Nationally, new firearm purchasers in 2020 and 2021 were more likely to be female, Black, or Hispanic (Miller et al. 2022). Handgun acquisition has been associated with large increases in firearm suicide risk, with a hazard ratio of nearly 8 among men and over 35 among women (Studdert et al. 2020). Despite this purchasing surge and the high lethality of firearm suicide attempts (Conner et al. 2019; Spitzer et al. 2020), few studies have examined pandemic-era trends in firearm suicide specifically, and none have looked at California, the most populous and diverse state in the USA.

The current study examines deaths by suicide and deaths by firearm suicide from 2017 through 2021 in California. Our aim is to assess changes in suicide during the first two years of the COVID-19 pandemic and determine whether changes varied by sociodemographic groups. We assess both counts and rates to evaluate different dimensions of the problem. Counts indicate population burden by identifying groups with the highest number of suicide deaths, while rates allow for between-group comparisons and reveal disparities in how different groups experience suicide.

Methods

Data

We used publicly available data on suicide from the California Department of Public Health – Vital Records Data (Cal-ViDa) query tool. The data contain statewide counts of deaths that occurred in California from January 1, 2017 to December 31, 2021, including information on decedents’ race and/or ethnicity (non-Hispanic white; non-Hispanic Black; non-Hispanic Asian; non-Hispanic Native American or Alaskan Native [AI/AN]; non-Hispanic Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander [NH/PI]; Hispanic; or Other, which includes multi-race, other, and unknown), education level (Bachelor’s degree and higher or less than a Bachelor’s degree), gender identity (male or female), age (10–19, 20–29, 30–44, 45–64, 65+), county of residence (grouped by urbanicity according to the US Department of Agriculture’s Rural-Urban Continuum Codes [RUCCs], displayed in Additional file 1: Table S1), and cause of death, coded using the International Classification of Disease, 10th Revision (ICD-10) (State of California DoPH 2022). Deaths by suicide were defined using ICD-10 codes for intentional self-harm by discharge of firearms (X72-X74) and by other and unspecified means (*U03, X60-X71, X75-X84, Y87.0).

As in prior research, given the small number of cases coded as suicide among people under the age of 10 (Fatal Injury Reports, National, Regional, and States 2020), we restricted our sample to people aged 10 years and older. We used race and Hispanic ancestry/origin (race/ethnicity) as proxies for sociocultural differences which may modify risk for self-harm (Oquendo et al. 2005; Molock et al. 2006) and for the effects of interpersonal and structural racism, including historical redlining, residential and social segregation, punitive immigration policy, mass incarceration, and the concentration and transmission of intergenerational trauma (Bailey et al. 2017; Gee and Ford 2011; Forster et al. 2019; Morgan et al. 2022; Hawthorne et al. 2012; Owens et al. 2011; Primm et al. 2010), which are risk factors for self-harm.

Analysis

We described rates and counts of fatal self-harm in California across our study period, comparing differences before and during the pandemic by method of suicide (firearm vs. any method) and across sociodemographic groups and geographic areas. To calculate suicide rates, we used estimates of the population aged 10 and older from the publicly available American Community Survey, 2017–2020 5-year estimates.

We compared monthly and annual counts and rates in 2020 and 2021 (which we refer to as “following the onset of the pandemic”) to the average of the 2017, 2018, and 2019 annual counts and rates (which we refer to as “pre-pandemic”). Only annual counts and rates were disaggregated by sociodemographic groups and geographic areas due to low monthly counts. To produce estimates for suppressed small numbers (Cal-ViDa data indicate “< 10” for all cell sizes 1–9), we used a single imputation technique developed for public health data which uses data in years prior to or after a missing cell to inform replacement, and mean imputation by year for the remaining missing values (Erdman et al. 2021). Up to 35% of Cal-ViDa observations had missing data (primarily due to suppressed county-level suicide counts in small counties). All statistical analyses were done using R version 4.1.2 (R Core Team 2020).

Results

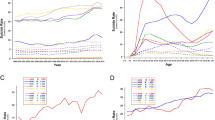

There was a total of 8227 suicides in California in the two years following the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic: 4123 (10.5 per 100,000) in 2020 and 4104 (10.4 per 100,000) in 2021 (Figs. 1A and 2A; Additional file 1: Tables S2 and S3). Pre-pandemic, the state-wide suicide burden was higher, with an average of 4484 deaths per year (11.4 per 100,000) in 2017–2019. Following the onset of the pandemic, there was also a slight decline in firearm suicides, with 1618 deaths (4.1 per 100,000) pre-pandemic, 1550 deaths (3.9 per 100,000) in 2020, and 1564 deaths (4.0 per 100,000) in 2021. Monthly trends in suicide and firearm suicide across the study period are given in Additional file 1: Fig. S1 and Additional file 1: Table S5. Because the decline in overall suicide was greater than the decline in firearm suicides, the proportion of suicides involving a firearm (36.1% pre-pandemic) increased slightly by 1.5% and 2.0%, in 2020 and 2021, respectively (Additional file 1: Table S4).

Counts of suicide in California from 2017 to 2021, by method of harm (A) in total population, and stratified by (B) sex (C) highest level of education (D) urbanicity (E) race/ethnicity and (F) age group. 1All race/ethnicity categories besides Hispanic and Other are non-Hispanic. 2AI/AN = American Indian (Native American)/Alaskan Native. 3NH/PI = Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander. *Counts of 30 or less. **Note: Y-axis scales differ across panels

Rates of suicide in California from 2017 to 2021, by method of harm (A) in total population, and stratified by (B) sex (C) highest level of education (D) urbanicity (E) race/ethnicity and (F) age group. 1All race/ethnicity categories besides Hispanic and Other are non-Hispanic. 2AI/AN = American Indian (Native American)/Alaskan Native. 3NH/PI = Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander. *Rate is based on counts of 30 or less

Across the study period, suicide and firearm suicide counts and rates were higher among males compared to females (Figs. 1B and 2B; Additional file 1: Tables S2 and S3). Males consistently represented about 78% of all suicides and about 90% of firearm suicides in California. In the total population, counts and rates of suicide decreased by approximately 8% in 2020 compared to pre-pandemic; however, in 2021, females experienced a greater decline (about 12% reduction) compared to pre-pandemic than did males (about 8% reduction). The burden of firearm suicide increased slightly among females in 2020 compared to pre-pandemic, with 14 more deaths from firearm suicide among females (an increase from 0.8 to 0.9 per 100,000), while the burden decreased among males that year, with 82 fewer firearm suicides (a reduction from 7.5 to 7.0 per 100,000). Consistently across the study period, firearm use in suicide was more common among males, with firearm suicides accounting for about 42–44% of all suicides among males and 16–19% of all suicides among females (Additional file 1: Table S4).

Rates and counts of suicide and firearm suicide varied by county urbanicity throughout the study period (Figs. 1D and 2D; Additional file 1: Tables S2 and S3). The highest number of suicides occurred in urban counties (metropolitan areas), but rural counties (nonmetropolitan areas) consistently had higher rates of suicide and firearm suicide. Compared to urban areas, rural areas saw a larger relative decrease in the proportion of suicides that involved a firearm in 2020 and 2021 compared to years prior (Additional file 1: Table S4).

The burden of and trends in suicide also differed across racial and ethnic groups (Figs. 1E and 2E; Additional file 1: Table S2 and S3). Non-Hispanic white Californians, who comprise 37% of the total population, had the highest number of suicides, accounting for over half of all suicides and firearm suicides in the state in all years of the study period. Hispanic Californians consistently accounted for the next largest number of suicides and firearm suicides, followed by Asian, Black, Other, AI/AN, and NH/PI Californians. Rates of suicide and firearm suicide were generally highest among white Californians, with AI/AN, NH/PI, and Black Californians experiencing the next highest rates. Hispanic and Asian Californians had the lowest rates of suicide and firearm suicide across the study period.

The state-wide decrease in suicide following the onset of the pandemic was not felt or distributed evenly across racial and ethnic groups. For instance, compared to pre-pandemic, non-Hispanic white Californians experienced 348 fewer suicide deaths (a reduction from 19.4 to 17.0 per 100,000) in 2020 and 445 fewer (a reduction from 19.4 to 16.4 per 100,000) in 2021. In contrast, Black Californians experienced 23 more deaths (an increase from 8.7 to 9.8 per 100,000) both in 2020 and 2021, compared to years prior. Though modest, Black Californians also had the highest and most stable increase in firearm suicides following the onset of the pandemic, with 17 more deaths (an increase from 2.8 to 3.6 per 100,000) in 2020 and 21 more deaths (an increase from 2.8 to 3.8 per 100,000) in 2021, compared to other racial/ethnic groups, all of whom experienced a decrease or no change in at least one of the years.

The burden of and changes in suicide and firearm suicide also varied by age group (Figs. 1F and 2F; Additional file 1: Table S2 and S3). In all years of the study period, Californians aged 30 to 64 accounted for the most suicide deaths (56–58%), while Californians aged 45 to 65+ accounted for the most firearm suicide deaths (61–66%). Rates were higher with increasing age, with people aged 10 to 19 having the lowest rates of suicide (4.0–4.4 per 100,000) and firearm suicide (1.1–1.2 per 100,000), and people aged 65 + having the highest rates of suicide (16.1–16.7 per 100,000) and firearm suicide (9.3–9.8 per 100,000). In 2020, however, young people aged 10 to 19 experienced 21 more suicides (an increase from 4.0 to 4.4 per 100,000) compared to pre-pandemic, while all other age groups saw a decline. The largest decline was among people aged 45–64, who had nearly 300 fewer suicides (a reduction from 16.0 to 13.0 per 100,000) in 2020 compared to pre-pandemic. People aged 65+ who died by suicide were consistently the most likely to use a firearm (Additional file 1: Table S4). Compared to pre-pandemic, the largest increase in the proportion of suicides that involved a firearm was among people aged 65+ in 2020 (from 57.0 to 60.2%) and among people aged 20 to 29 in 2021 (from 27.4 to 33.1%).

Discussion

During the first two years following the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, the incidence of suicide declined state-wide in California, while firearm suicide rates declined much more modestly. Differential variation by sociodemographic groups and geographic areas underlay these trends, suggesting differential exposure to or impact of pandemic-era risk and protective factors, and a need for tailored allocation of state resources and prevention efforts.

The overall decline in state-wide suicide rates during and following the onset of the pandemic parallels similar findings from other states (Faust et al. 2021; Mitchell and Li 2021; Bray et al. 2021), and the slight decline in firearm suicide rates aligns with recent CDC data released indicating firearm suicide rates remained level between 2019 and 2020 (Kegler et al. 2022). In California, the overall decline was driven by meaningful reductions in suicide among the groups most burdened by suicide: male, middle-aged, and white Californians. In contrast, groups typically at lower risk—female, young, Black, and Hispanic Californians—experienced increases or relatively smaller decreases in suicide or firearm suicide.

As in prior research, we found that males in California consistently had a higher risk of suicide (Callanan and Davis 2012). However, females experienced a slight increase in firearm suicide in 2020 compared to pre-pandemic, while males experienced a decrease. These results may reflect the fact that the recent firearm purchasing surge led to uniquely higher firearm ownership among groups historically less likely to own firearms (e.g., women) and may indicate a potential shift toward more lethal methods among this group (Miller et al. 2022).

Young people (ages 10 to 19) in California experienced an increase in suicide in 2020 and 2021 compared to years prior, a trend mirroring national findings (Kegler et al. 2022). This is especially concerning given that suicide is the second leading cause of death for young people in California and nationally (California Department Public Health 2018; CDC. CDC WONDER 2020). The magnitude of the increase among young people was not shared by any other age groups, most of whom experienced a decrease in suicide. Preventative efforts, including lethal means safety and mental health supports, should be prioritized for adolescents and young adults—who were uniquely impacted by recent social isolation, uncertainty, stress, and fear—given their stage of life and the importance of socialization for healthy development (Viner et al. 2022; United Nations 2020).

White Californians experienced substantial declines in suicide and firearm suicide during the pandemic, a trend aligned with national findings (Stone et al. 2023). Given the size of the white population and the magnitude of suicide burden among this group, this decrease drove the overall decline observed in the aggregated data. By disaggregating the data, we discovered unique trends across distinct communities. For instance, Black, Hispanic, Asian, and AI/AN Californians all experienced an increase in suicide and/or firearm suicide in at least one of the years following the onset of the pandemic. Compared to all other racial/ethnic groups, Black Californians experienced the largest relative increase in suicide and firearm suicide following the onset of the pandemic. These findings are consistent with studies in Maryland and Connecticut documenting an increase in suicide mortality among Black residents and a decrease among white residents in the months following the onset of the pandemic compared to earlier time periods (Mitchell and Li 2021; Bray et al. 2021), and with national, pre-pandemic trends showing a greater increase in suicidal behavior among Black Americans, particularly youth, compared to white Americans, from 1991 to 2019 (Xiao et al. 2021).

It is likely the racial/ethnic disparities we identified are related, in part, to the pandemic-driven amplification of the structural inequities that shape population health in the USA (Gravlee 2020) and diminshment of culturally specific factors protective of suicide. The communities most burdened by the health, economic, and social crises of 2020 and 2021 already faced disproportionate threats to their health as a result of systemic racism (Bailey et al. 2017) and other systems of marginalization that concentrate greater risk factors associated with suicide (e.g., poverty, unemployment, and mass incarceration (Gee and Ford 2011; Morgan et al. 2022)) and fewer protective factors (e.g., quality education, economic development, and culturally competent mental healthcare (Hawthorne et al. 2012; Owens et al. 2011; Primm et al. 2010)). Further, Black and Latino Americans, who attend church at higher rates than white Americans (Pew Research Center 2014), may have been disproportionately impacted by the restricted ability to gather for religious worship; and religiosity has been linked to reduction in suicide risk (Molock et al. 2006; Lawrence et al. 2016). In addition, COVID-19 increased economic and labor market disparities along racial lines (Wilson 2020), which have been connected to increased risk of suicide (Wadsworth and Kubrin 2007). Finally, perceived racial discrimination, which increased during the pandemic (Martínez-Alés et al. 2022; Wang et al. 2021), along with disparities in death from COVID-19 and police killings (Wilson 2020; Martínez-Alés et al. 2022), has also been connected to suicide risk among racially/ethnically minoritized groups (Wang et al. 2021; Mpofu et al. 2022).

Another factor potentially contributing to the increase in suicide, particularly firearm suicide, among some groups may be the firearm purchasing surge of 2020 and 2021. There is an established connection between firearm access and risk of firearm suicide (Studdert et al. 2020; Kellermann et al. 1992; Miller et al. 2002; Wintemute et al. 1999), and surges in firearm purchasing, which California experienced at the onset of the pandemic, are associated with increases in firearm violence (Levine and McKnight 2017; Laqueur et al. 2019). Further, a national study found that pandemic-era firearm purchasers were more likely to experience suicidality than non-owners and pre-pandemic purchasers (Anestis et al. 2021). While we did not observe an increase in number of firearm suicides following the onset of the pandemic, the increase in proportion of suicides that involve a firearm could indicate a trend toward an increasing use of firearms for self-harm, even amid an overall decreasing trend in death by suicide. Further, while nonurban areas saw a decrease in the proportion of suicides that involve a firearm, urban areas saw an increase. This may reflect the fact that the purchasing surge of 2020 and 2021 was especially pronounced in urban areas (Miller et al. 2022). Additionally, suicide modestly increased in rural areas in 2021, compared to pre-pandemic, while firearm suicide decreased, which may point to greater use of non-firearm means of suicide in California’s rural population—a finding which does not align with historical trends or findings from other contexts (Nestadt et al. 2017; Branas et al. 2004). Future studies with more granular data on method of suicide should explore these questions. Either way, investment in firearm violence prevention strategies—including education on safe storage practices and promotion of extreme risk protection orders (Pear et al. 2022)—may help reduce risk for firearm suicide.

For white populations and others who experienced a decline in suicide during the pandemic, a few potentially protective factors introduced during this period may have buffered or modified the expected association between the stressors of 2020 and 2021 and risk for suicide. For instance, a sense of shared experience may have offset the lack of social interaction by creating a feeling of collective purpose (Schaefer et al. 2013). In addition, people who lived with others during the stay-at-home order may have been alone less often or under higher levels of supervision or scrutiny within their home, which may have reduced self-harm. Reductions in in-person healthcare appointments at the start of the pandemic led to the widespread adoption of telehealth, which may have increased some individuals’ access to mental healthcare (Myers 2019). Finally, COVID-19 relief payments may have offset financial strain for some (Kim 2021). Each of these potentially protective factors is likely differential based on one’s access to remote work and other economic protections; non-Hispanic white and male Californians are relatively advantaged in both regards (Asfaw 2022), which could help explain the decline in suicide those groups experienced.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to assess incidence of firearm suicide across sociodemographic groups in California following the onset of the pandemic. There are, however, several limitations. First, due to data availability, we are only able to stratify deaths by suicide across one method (i.e., firearm). As such, we cannot pinpoint the method of suicide driving observed changes. Further, our inability to stratify death data across more than one domain restricts the nuance of our analyses. Future research should characterize risk across the intersection of multiple groups and compare changes in other methods of suicide.

Conclusions

In California, the groups most burdened by suicide—males, middle-aged, and white Californians—experienced meaningful decreases in suicide following the onset of the pandemic, driving decreases in overall population rates, while females, young, Black, and Hispanic Californians experienced increases or small decreases, worsening existing health inequities. Identifying factors underlying these trends may inform our understanding of the epidemiology of suicide in various communities. Our findings highlight the need for targeted interventions addressing structural inequities, such as implementation of more social supports and provision of basic needs; suicide prevention interventions, such as improved access to quality mental healthcare, expansion of bereavement counseling, and better suicide risk assessments; and firearm safety efforts, such as trainings on safe storage practices and education about extreme risk protection orders, all of which could reduce suicide and promote equitable opportunity for health and wellness across the state.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset of deaths in California generated and analyzed during the current study are publicly available in the California Department of Public Health – Vital Records Data (Cal-ViDa) query tool repository, https://cal-vida.cdph.ca.gov/ (State of California DoPH. California Vital Data (Cal-ViDa). 2022).

Abbreviations

- AI/AN:

-

Native American or Alaskan Native

- Cal-ViDA:

-

California Department of Public Health – Vital Records Data

- ICD-10:

-

International Classification of Disease, 10th Revision

- NH:

-

Non-Hispanic

- NH/PI:

-

Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander

- PTSD:

-

Posttraumatic stress disorder

- SARS:

-

Severe acute respiratory syndrome

- UC:

-

University of California

- USA:

-

United States of America

References

Abelson R. Social isolation in the U.S. rose even as the Covid crisis began to subside, new research shows. New York Times. 2021, July 8.

Ammerman BA, Burke TA, Jacobucci R, McClure K. Preliminary investigation of the association between COVID-19 and suicidal thoughts and behaviors in the U.S. J Psychiatr Res. 2021;134:32–8.

Anestis MD, Bond AE, Daruwala SE, Bandel SL, Bryan CJ. Suicidal ideation among individuals who have purchased firearms during COVID-19. Am J Prev Med. 2021;60(3):311–7.

Asfaw A. Racial and ethnic disparities in teleworking due to the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States: a mediation analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(8):4680.

Bailey ZD, Krieger N, Agenor M, Graves J, Linos N, Bassett MT. Structural racism and health inequities in the USA: evidence and interventions. Lancet. 2017;389(10077):1453–63.

Batty GD, Kivimäki M, Bell S, Gale CR, Shipley M, Whitley E, et al. Psychosocial characteristics as potential predictors of suicide in adults: an overview of the evidence with new results from prospective cohort studies. Transl Psychiatry. 2018;8(1):22.

Branas CC, Nance ML, Elliott MR, Richmond TS, Schwab CW. Urban-rural shifts in intentional firearm death: different causes, same results. Am J Public Health. 2004;94:1750–5.

Bray MJC, Daneshvari NO, Radhakrishnan I, Cubbage J, Eagle M, Southall P, et al. Racial differences in statewide suicide mortality trends in Maryland during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. JAMA Psychiat. 2021;78(4):444–7.

Bühler JL, Hopwood CJ, Nissen A, Bleidorn W. Collective stressors affect the psychosocial development of young adults. Soc Psychol Personal Sci. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1177/19485506221119018.

Caballero-Domínguez CC, Jiménez-Villamizar MP, Campo-Arias A. Suicide risk during the lockdown due to coronavirus disease (COVID-19) in Colombia. Death Stud. 2022;46(4):885–90.

California Department Public Health. Preventing violence in California: data brief 1: overview of homicide and suicide deaths in California. Sacramento, CA; 2018.

Callanan VJ, Davis MS. Gender differences in suicide methods. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2012;47(6):857–69.

CDC. CDC WONDER: underlying cause of death, 1999–2019. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2020.

Cheung YT, Chau PH, Yip PS. A revisit on older adults suicides and severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) epidemic in Hong Kong. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;23(12):1231–8.

Conner A, Azrael D, Miller M. Suicide case-fatality rates in the United States, 2007 to 2014: a nationwide population-based study. Ann Intern Med. 2019;171(12):885–95.

Elbogen EB, Lanier M, Montgomery AE, Strickland S, Wagner HR, Tsai J. Financial strain and suicide attempts in a nationally representative sample of US adults. Am J Epidemiol. 2020;189(11):1266–74.

Erdman EA, Young LD, Bernson DL, Bauer C, Chui K, Stopka TJ. A novel imputation approach for sharing protected public health data. Am J Public Health. 2021;111(10):1830–8.

Fatal Injury Reports, National, Regional, and States (restricted) [Internet]. 2020 [cited September 13, 2022]. Available from: www.cdc.gov/ncipc/wisqars.

Faust JS, Shah SB, Du C, Li SX, Lin Z, Krumholz HM. Suicide deaths during the COVID-19 stay-at-home advisory in Massachusetts, March to May 2020. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(1):e2034273.

Forster M, Davis L, Grigsby TJ, Rogers CJ, Vetrone SF, Unger JB. The role of familial incarceration and ethnic identity in suicidal ideation and suicide attempt: findings from a longitudinal study of Latinx young adults in California. Am J Community Psychol. 2019;64(1–2):191–201.

Fox MP, Murray EJ, Lesko CR, Sealy-Jefferson S. On the need to revitalize descriptive epidemiology. Am J Epidemiol. 2022;191(7):1174–9.

Gee GC, Ford CL. Structural racism and health inequities: old issues, new directions. Du Bois Rev. 2011;8(1):115–32.

Gravlee CC. Systemic racism, chronic health inequities, and COVID-19: a syndemic in the making? Am J Hum Biol. 2020;32(5):e23482.

Hawryluck L, Gold WL, Robinson S, Pogorski S, Galea S, Styra R. SARS control and psychological effects of quarantine, Toronto, Canada. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10(7):1206–12.

Hawthorne WB, Folsom DP, Sommerfeld DH, Lanouette NM, Lewis M, Aarons GA, et al. Incarceration among adults who are in the public mental health system: rates, risk factors, and short-term outcomes. Psychiatr Serv. 2012;63(1):26–32.

Kegler SR, Simon TR, Zwald ML, Chen MS, Mercy JA, Jones CM, et al. Vital Signs: changes in firearm homicide and suicide rates—United States, 2019–2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71(19):656–63.

Kellermann AL, Rivara FP, Somes G, Reay DT, Francisco J, Banton JG, et al. Suicide in the home in relation to gun ownership. N Engl J Med. 1992;327(7):467–72.

Kiang MV, Acosta RJ, Chen YH, Matthay EC, Tsai AC, Basu S, et al. Sociodemographic and geographic disparities in excess fatal drug overdoses during the COVID-19 pandemic in California: a population-based study. Lancet Reg Health Am. 2022;11:100237.

Kim D. Financial hardship and social assistance as determinants of mental health and food and housing insecurity during the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States. SSM Popul Health. 2021;16:100862.

Knipe D, John A, Padmanathan P, Eyles E, Dekel D, Higgins JPT, et al. Suicide and self-harm in low- and middle- income countries during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review. PLOS Global Public Health. 2022;2(6):e0000282.

Kravitz-Wirtz N, Aubel A, Schleimer J, Pallin R, Wintemute G. Public concern about violence, firearms, and the COVID-19 pandemic in California. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(1):e2033484-e.

Laqueur HS, Kagawa RMC, McCort CD, Pallin R, Wintemute G. The impact of spikes in handgun acquisitions on firearm-related harms. Inj Epidemiol. 2019;6(1):35.

Lawrence RE, Oquendo MA, Stanley B. Religion and suicide risk: a systematic review. Arch Suicide Res. 2016;20(1):1–21.

Levine PB, McKnight R. Firearms and accidental deaths: evidence from the aftermath of the Sandy Hook school shooting. Science. 2017;358(6368):1324–8.

Martínez-Alés G, Jiang T, Keyes KM, Gradus JL. The recent rise of suicide mortality in the United States. Annu Rev Public Health. 2022;43(1):99–116.

Miller M, Azrael D, Hemenway D. Firearm availability and suicide, homicide, and unintentional firearm deaths among women. J Urban Health. 2002;79(1):26–38.

Miller M, Zhang W, Azrael D. Firearm Purchasing During the COVID-19 pandemic: results from the 2021 national firearms survey. Ann Intern Med. 2022;175(2):219–25.

Mitchell TO, Li L. State-level data on suicide mortality during COVID-19 quarantine: early evidence of a disproportionate impact on racial minorities. Psychiatry Res. 2021;295:113629.

Molock SD, Puri R, Matlin S, Barksdale C. Relationship between religious coping and suicidal behaviors among African American adolescents. J Black Psychol. 2006;32(3):366–89.

Morgan ER, Rivara FP, Ta M, Grossman DC, Jones K, Rowhani-Rahbar A. Incarceration and subsequent risk of suicide: a statewide cohort study. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2022;52(3):467–77.

Mpofu ACJ, Ashley C, Geda S, Harding RL, Johns M, Spinks-Franklin A, Njai R, Moyse D, Underwood JM. perceived racism and demographic, mental health, and behavioral characteristics among high school students during the COVID-19 pandemic—adolescent behaviors and experiences survey, United States, January–June 2021. MMWR Suppl. 2022;71:22–7.

Myers CR. Using Telehealth to Remediate Rural Mental Health and Healthcare Disparities. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2019;40(3):233–9.

Nestadt PS, Triplett P, Fowler DR, Mojtabai R. Urban–rural differences in suicide in the state of Maryland: the role of firearms. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(10):1548–53.

Office of Governor Gavin Newsom. Executive Order N-33-20. In: California EDSo, editor. 2020.

Ontiveros ST, Levine MD, Cantrell FL, Thomas C, Minns AB. Despair in the time of COVID: a look at suicidal ingestions reported to the California poison control system during the pandemic. Acad Emerg Med. 2021;28(3):300–5.

Oquendo MA, Dragatsi D, Harkavy-Friedman J, Dervic K, Currier D, Burke AK, et al. Protective factors against suicidal behavior in Latinos. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2005;193(7):438–43.

Owens GP, Rogers SM, Whitesell AA. Use of mental health services and barriers to care for individuals on probation or parole. J Offender Rehabil. 2011;50(1):37–47.

Pear VA, Pallin R, Schleimer JP, Tomsich E, Kravitz-Wirtz N, Shev AB, et al. Gun violence restraining orders in California, 2016–2018: case details and respondent mortality. Inj Prev. 2022;28(5):465–71.

Pew Research Center. Attendance at religious services by race/ethnicity. 2014.

Pew Research Center. “Economic Fallout From COVID-19 Continues To Hit Lower-Income Americans the Hardest”. 2020.

Pirkis J, John A, Shin S, DelPozo-Banos M, Arya V, Analuisa-Aguilar P, et al. Suicide trends in the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic: an interrupted time-series analysis of preliminary data from 21 countries. Lancet Psychiatry. 2021;8(7):579–88.

Primm AB, Vasquez MJ, Mays RA, Sammons-Posey D, McKnight-Eily LR, Presley-Cantrell LR, et al. The role of public health in addressing racial and ethnic disparities in mental health and mental illness. Prev Chronic Dis. 2010;7(1):A20.

R Core Team. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. In: For RF, statistical computing V, Austria, editors. 2020.

Reeves A, Stuckler D, McKee M, Gunnell D, Chang S-S, Basu S. Increase in state suicide rates in the USA during economic recession. Lancet. 2012;380(9856):1813–4.

Schaefer SM, Morozink Boylan J, van Reekum CM, Lapate RC, Norris CJ, Ryff CD, et al. Purpose in life predicts better emotional recovery from negative stimuli. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(11):e80329.

Schleimer JP, McCort CD, Shev AB, Pear VA, Tomsich E, De Biasi A, et al. Firearm purchasing and firearm violence during the coronavirus pandemic in the United States: a cross-sectional study. Inj Epidemiol. 2021;8(1):43.

Silver RC, Holman EA, Garfin DR. Coping with cascading collective traumas in the United States. Nat Hum Behav. 2021;5(1):4–6.

Spitzer SA, Pear VA, McCort CD, Wintemute GJ. Incidence, distribution, and lethality of firearm injuries in California from 2005 to 2015. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(8):e2014736.

State of California DoPH. California Vital Data (Cal-ViDa), Death Query. https://cal-vida.cdph.ca.gov/, Last modified 10 July 2022.

Stone DM, Mack KA, Qualters J. Notes from the field: recent changes in suicide rate, by race and ethnicity and age group—United States, 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023;72:160–2.

Studdert DM, Zhang Y, Swanson SA, Prince L, Rodden JA, Holsinger EE, et al. Handgun ownership and suicide in California. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(23):2220–9.

United Nations. Policy brief: the impact of COVID-19 on children. 2020.

Verdery AM, Smith-Greenaway E, Margolis R, Daw J. Tracking the reach of COVID-19 kin loss with a bereavement multiplier applied to the United States. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020;117(30):17695–701.

Viner R, Russell S, Saulle R, Croker H, Stansfield C, Packer J, et al. School closures during social lockdown and mental health, health behaviors, and well-being among children and adolescents during the first COVID-19 wave: a systematic review. JAMA Pediatr. 2022;176(4):400–9.

Wadsworth T, Kubrin CE. Hispanic suicide in U.S. metropolitan areas: examining the effects of immigration, assimilation, affluence, and disadvantage. Am J Sociol. 2007;112(6):1848–85.

Wang L, Lin H-C, Wong YJ. Perceived racial discrimination on the change of suicide risk among ethnic minorities in the United States. Ethn Health. 2021;26(5):631–45.

Wasserman IM. The impact of epidemic, war, prohibition and media on suicide: United States, 1910–1920. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 1992;22(2):240–54.

Wilson V. Inequities exposed: how COVID-19 widened racial inequities in education, health, and the workforce. Testimony before the US House of Representatives Committee on Education and Labor Economic Policy Institute, Washington, DC. 2020.

Wintemute GJ, Parham CA, Beaumont JJ, Wright M, Drake C. Mortality among recent purchasers of handguns. N Engl J Med. 1999;341(21):1583–9.

Xiao Y, Cerel J, Mann JJ. Temporal trends in suicidal ideation and attempts among US adolescents by sex and race/ethnicity, 1991–2019. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(6):e2113513-e.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported by the Joyce Foundation (Grant No. 42400), the Heising-Simons Foundation (Grant No. 2019-1728), and the California Firearm Violence Research Center.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JL analyzed the data and wrote the original draft. ET contributed substantially to writing. JS and VP contributed substantially to conceptualization. ET, JS, and VP interpreted data output, reviewed, and edited the draft. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The University of California, Davis Institutional Review Board approved this study. All methods were performed in accordance with the ethical standards as laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent was not required for this secondary data analysis.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1

. Figure S1: Rates of suicide and firearm suicide in California from 2017–2021, by month. Table S1: California counties categorized as rural/urban according to the US Department of Agriculture’s Rural-Urban Continuum Codes (RUCCs). Table S2: Counts of suicide and firearm suicide in California from 2017–2021, by sociodemographic characteristics. Table S3: Rates of suicide and firearm suicide in California from 2017–2021, by sociodemographic characteristics. Table S4: Proportion of suicides that involved a firearm in California from 2017–2021, by sociodemographic characteristics. Table S5: Counts and rates of suicide and firearm suicide in California from 2017–2021, by month.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Lund, J.J., Tomsich, E., Schleimer, J.P. et al. Changes in suicide in California from 2017 to 2021: a population-based study. Inj. Epidemiol. 10, 19 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40621-023-00429-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40621-023-00429-6