Abstract

Background

Although falls are common and can cause serious injury to older adults, many health care facilities do not have falls prevention resources available. Falls prevention resources can reduce injury and mortality rates. Using the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) Stopping Elderly Accidents, Deaths & Injuries (STEADI) model, a falls risk clinic was implemented in a rural Indian Health Service (IHS) facility.

Methods

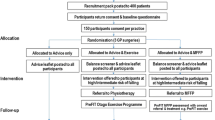

A Fall Risk Questionnaire was created and implemented into the Provider’s Electronic Health Records system interface to streamline provider screening and referral of patients who may be at risk for falls to a group falls risk reduction class.

Results

Participants exhibited average improvements in the Timed Up and Go (6.8 s) (P = 0.0001), Five-Time Sit-to-Stand (5.1 s) (P = 0.0002), and Functional Reach (3.6 inches) (P = 1.0) tests as compared to their own baseline. Results were analyzed via paired t test. 71% of participants advanced out of an “increased risk for falls” category in at least one outcome measure. Of the participants to complete the clinic, all were successfully contacted and three (18%) reported one or more falls at the 90-day mark, of which one (6%) required a visit to the Emergency Department but did not require hospital admission.

Conclusions

In regards to reducing falls in the community, per the CDC STEADI model, an integrated approach is best. All clinicians can play a part in reducing elder falls.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Coming of age beyond adulthood means different things to different cultures. The traditional notion of the respectful elder has been overtaken by the western obsession of youth. On many American Indian/Alaska Native (AI/AN) reservations, however, the former thought still prevails. Indigenous elders are vital to their respective societies (Viscogliosi et al. 2020). Elders are cultural gatekeepers and teachers of traditions, stories, and skills in nations that are trying desperately to remain intact (Viscogliosi et al. 2020).

“Unintentional injury” is the #7 cause of death in adults over 65 in the USA. 57% of the deaths in that category occurred by falling which make falling the leading cause of Unintentional Injury-related deaths for this age group (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2018a, b). If a fall is severe enough to warrant a hospital admission, the 1-year mortality rate of that individual is 50% (Klak et al. 2017). Many patients and health care personnel may also be under-informed as to the impact a fall can have on overall health, which may cause further complications bordering on iatrogenic (Hill et al. 2009; Shuman et al. 2016). During the most recent 5 year period, 1159 AI/ANs died due to a fall, with the death rates dramatically increasing from 9.31/100,000 population among 60–64 year olds to 67.33/100,000 among 80–84 year olds and 146.97/100,000 population among those 85+ years of age (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2021) (Fig. 1).

As compared with urban facilities, rural facilities are under-equipped, specialists are sparse, and medical services span larger geographical areas (Galambos 2005). In rural AI/AN communities, there are many low-income families and few own personal automobiles (Tiwari et al. 2015). Transportation issues are made worse by the poor road conditions that are found on many AI/AN reservations (Tiwari et al. 2015). These patients often have to rely on public transport or medical transit services that can be less than reliable (Tiwari et al. 2015).

In many instances, it is also possible for seemingly innocuous policies within health care companies to contribute to health disparities in rural populations. Though the Indian Health Service (IHS) does not operate in this way, it is not uncommon for private companies that provide home-health services to require their employees to meet a certain “productivity” obligation every pay period (Hellman 1991; Bly 1982). Productivity is mostly gained by treating patients but another way is the physical act of driving (Hellman 1991; Bly 1982). Once an employee hits a predetermined mileage quota, they may earn a production point in lieu of patient care. This means that for employees in rural areas who are driving further between homes (Galambos 2005), they are able to keep the same level of productivity while seeing fewer patients. As shown above, many different factors can lead to increasing health disparities between rural and urban health care.

This article examines the implementation and initial evaluation of a falls risk clinic, named the Community Health Injury Prevention (CHIP) Clinic, in an IHS facility. Many facilities lack a dedicated falls-related resource (Ayton et al. 2017), and the purpose of this article is to act as a scaffolding concept or a logistical framework in how to begin the implementation of such a resource. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) utilizes an evidence-based initiative called Stopping Elderly Accidents, Deaths & Injuries (STEADI) that seeks to reduce elder falls and injury (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2020). STEADI requires health care providers to Screen, Assess, and Intervene as part of the model (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2019, 2020). Because physicians, nurses, and pharmacists are likely to be the first point of contact in one’s care, they are crucial in their roles in the STEADI model, especially in regards to prescribing opioids, which are both frequently used by older adults and have been linked to increased falls (Ojha et al. 2014; Huang et al. 2012; Machado-Duque et al. 2018). Because Physical Therapists (PTs) spend, on average, more face-to-face time with patients than physicians and pharmacists (Murphy et al. 2005), they too are important to the STEADI process and can assume the brunt of the assessment and intervention role, while effective screening can be assumed by physicians in most medical models.

Methods

Screening

A 5-item questionnaire, the Falls Likelihood Injury Prevention Questionnaire (FLIP-Q), was created for the falls risk clinic and uploaded to the facility’s Electronic Health Records (EHR) template. The questionnaire is as follows (Fig. 2) (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2019; Whitney et al. 2005; Nazarko 2006).

Each time a patient who meets the above criteria presents for a visit, providers are prompted to answer these five questions. An affirmative answer to any question will prompt a PT referral for a falls risk assessment and intervention, as described below.

Assessment

The first of three group classes encompasses education, subjective history, assistive device assessment, completion of outcome measures, and instruction in a Home Exercise Program (HEP) which is to begin immediately and performed daily. Education consists of sharing mortality rates from falling, proper sitting/standing technique, proper footwear inside and outside the home, throw-rug/clutter removal in the home, and education on how pets might increase the risk for falls. The outcome measures performed in the first class are the Timed Up and Go (Whitney et al. 2005) (TUG) (dynamic balance test), the Five-Time Sit-to-Stand (Bohannon et al. 2007) (5xSTS) (lower-extremity strength test), and the Functional Reach (Weiner et al. 1992) (FR) (dynamic balance test).

Intervention

During the second and third class, the HEP is performed. This allows a time for the clinicians (PTs/OTs) to assess compliance, as well as further promote correct form with all exercises. The second and third class also has participants complete higher-level dynamic balance exercises. At the beginning of the third class, the outcome measures are tested again and differences are noted.

The decisions made based on outcome measure performance use risk stratification levels as described by validated tests. Patients attending this class should be able to safely complete the TUG and 5xSTS in ≤ 15 s (Whitney et al. 2005; Bohannon et al. 2007) and should be able to score ≥ 7 inches on the FR (Weiner et al. 1992). Scores outside these safety thresholds result in an individual being placed into a higher risk for falls (Whitney et al. 2005; Bohannon et al. 2007; Weiner et al. 1992). If a patient is within the safety thresholds of all three measures, they are not compelled to complete the entirety of the clinic and are discharged. If a patient is within the “higher falls risk” category in any one of the outcome measures, they are considered appropriate for completion of the full CHIP class and only the improvement in measures in which they scored outside the safety threshold will be tracked. Therapists will make a decision on whether or not each patient will continue PT on an individual basis at the completion of the clinic.

Follow-up appointments or questionnaires are another vital component to comprehensive falls risk reduction clinics (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2019, 2020; Hauer et al. 2001; Shen et al. 2015). This CHIP clinic utilizes the following 90-day follow-up questionnaire: Have you had a fall in the last 90 days since the completion of the CHIP class? If yes, did this fall send you to the Emergency Department? If yes, were you admitted to a facility due to injuries resulting from the fall?

Results

In the first 9 months of the CHIP clinic, providers screened over 2100 patients using the FLIP-Q. Of those who required further evaluation (N = 192) by the PT department, 17 completed all three classes; 165 people did not finish the entire clinic either because they scored within all safety thresholds or due to some other extenuating circumstance, 10 referrals were unable to be contacted via telephone or mail. Of the 17 participants who completed the program, there was an average TUG improvement of 6.8 s (P = 0.0001), an average 5xSTS improvement of 5.1 s (P = 0.0004), and an average FR improvement of 3.6″ (P = 1.0). Results were analyzed using a paired t test. 71% of participants advanced out of a “falls risk” category in at least one outcome measure. All participants were successfully contacted and three of the 17 patients (18%) reported falls at the 90-day mark, and one of these patients (6%) made a visit to the Emergency Department but did not require hospital admission (Table 1; Fig. 3).

Due to scoring within the safety threshold before completing any physical aspect of the class, three participants (14%) did not have their TUG tracked, four participants (19%) did not have their 5xSTS tracked, and 14 participants (82%) did not have their FR tracked. It is important to note that the only people completing this class in its entirety scored outside of the safety threshold in at least one of the three outcome measures at their initial visit (Table 2).

Discussion

We found that two measures, the TUG and the 5xSTS, both improved significantly among older adults at risk for falls. The improvement in the FR was not determined to be statistically significant due to the small number of patients who were required to complete both FR tests. 82% of the participants who completed the class and scored outside of the safety threshold of the TUG and/or 5xSTS scored within the safety threshold of the FR. Based on these data, it appears that the FR is quite specific for increased falls risk, and reaching less than 7″ might be indicative of patients who are at a very high risk for falls.

There are limitations to note with this clinic, some of which stem from the fact that the population served by this clinic is rural and mostly low-income. Many of these patients are relying on medical transport, which may not get them to their appointment on time, if at all. There is also a fair number of patients living within the reservation served by this facility who only speak their native language (United States Census Bureau 2020). A 2011 study reported that only 78.8% of the Natives living in this area spoke English “very well.” (United States Census Bureau 2020) It is possible that some parts of the education from the CHIP class and the importance of consistent attendance are not communicated well due to the lack of specific native-language handouts. Though interpreters are used during the CHIP program, some of this information may be lost in translation, so to speak. This article is meant to serve as a template as to how and why one should get started in creating a falls prevention initiative in a facility that services a rural population. Though the sample size is small, the success of this clinic lies in its use of evidence-based tools and overall positive results.

Conclusion

Following evidence-based practice is crucial when creating a new initiative of any type. In regards to reducing falls, per the CDC STEADI model, an integrated approach including screening, assessment, and intervention is best (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2020). All clinicians can play a part when working to reduce falls. It is also important to partner with as many appropriate team members as possible. This creates a pool of resources and ideas. These partners may include the admin board and IT department (they have the authority to approve additions to EHR templates; this was required with the implementation of the FLIP-Q), community health representatives to initiate home visits, environmental health personnel to assist with performing home-safety modifications, and existing community coalitions/programs or injury prevention initiatives that are already performing this work. All the aforementioned were required for the CHIP clinic. This clinic is a great example of how clinical staff and community-based fall prevention programs can work together to prevent falls.

Many Native American/Alaska Native cultures find importance in honoring the sacred and protecting those most vulnerable, including and especially their elders. Reducing elder falls can help families in AI/AN communities (and all rural communities) by freeing them from the burden of falls-related illness and injury. All clinicians can assist in this prevention effort and help rural and urban community members at higher risk for falls reduce injuries and live healthier lives.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Abbreviations

- 5xSTS:

-

Five-Time Sit-to-Stand Test

- CDC:

-

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- CHIP:

-

Community Health Injury Prevention

- FLIP-Q:

-

Falls Likelihood Injury Prevention Questionnaire

- FR:

-

Functional Reach Test

- HEP:

-

Home Exercise Program

- IHS:

-

Indian Health Service

- PT/PTs:

-

Physical Therapy, Physical Therapist/Physical Therapists

- STEADI:

-

Stopping Elderly Accidents, Deaths, and Injuries

- TUG:

-

Timed Up and Go Test

- USPHS:

-

United States Public Health Service

References

Ayton DR, et al. Barriers and enablers to the implementation of the 6-PACK falls prevention program: a pre-implementation study in hospitals participating in a cluster randomized controlled trial. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(1):e0171932. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0171932.

Bly JL. Measuring productivity for home health nurses. Home Health Care Serv Q. 1982;2(3):23–9.

Bohannon RW, et al. Five-repetition sit-to-stand test performance by community-dwelling adults: a preliminary investigation of times, determinants, and relationship with self-reported physical performance. Isokinet Exerc Sci. 2007;15(2):77–81.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS). 10 leading causes of death by age group, United States. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (producer). 2018a. Available from https://www.cdc.gov/injury/images/lc-charts/leading_causes_of_death_by_age_group_2018_1100w850h.jpg. Accessed 11 Nov 2020.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS). 10 leading causes of injury deaths by age group highlighting unintentional injury deaths, United States. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (producer). 2018b. Available from https://www.cdc.gov/injury/images/lc-charts/leading_causes_of_death_by_age_group_unintentional_2018_1100w850h.jpg. Accessed 11 Nov 2020.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. STEADI—Stopping Elderly Accidents, Deaths & Injuries. 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/steadi/pdf/STEADI-Algorithm-508.pdf.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. STEADI—Stopping Elderly Accidents, Deaths & Injuries. 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/steadi/materials.html. Accessed 12 Aug 2020.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS). Fatal Injury Reports, Unintentional Injury, Falls, United States (2015–2019). National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (producer). 2021. Available from https://www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/fatal.html. Accessed 4 May 2021.

Galambos CM. Health care disparities among rural populations: a neglected frontier. Health Soc Work. 2005;30(3):179–81.

Hauer K, et al. Exercise training for rehabilitation and secondary prevention of falls in geriatric patients with a history of injurious falls. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49(1):10–20.

Hellman EA. Analysis of a home health agency’s productivity system. Public Health Nurs. 1991;8(4):251–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1446.1991.tb00665.x.

Hill AM, et al. Evaluation of the effect of patient education on rates of falls in older hospital patients: description of a randomized controlled trial. BMC Geriatr. 2009;9(14):1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2318-9-14.

Huang AR, et al. Medication-related falls in the elderly. Drugs Aging. 2012;29:359–76.

Klak A, et al. A growing problem of falls in the aging population: a case study on Poland—2015–2050 forecast. Eur Geriatr Med. 2017;8(2):105–10.

Machado-Duque ME, et al. Association between the use of benzodiazepines and opioids with the risk of falls and hip fractures in older adults. Int Psychogeriatr. 2018;30(7):941–6.

Murphy BP, et al. Primary care physical therapy practice models. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2005;35:699–707.

Nazarko L. Falls prevention in practice: guidance and case study. Br J Commun Nurs. 2006;11(12):527–9.

Ojha HA, et al. Direct access compared with referred physical therapy episodes of care: a systematic review. Phys Ther. 2014;94(1):14–30.

Shen X, et al. Technology-assisted balance and gait training reduces falls in patients with Parkinson’s disease: a randomized controlled trial with 12-month follow-up. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2015;29(2):103–11.

Shuman C, et al. Patient perceptions and experiences with falls during hospitalization and after discharge. Appl Nurs Res. 2016;31:79–85.

Tiwari T, et al. Challenges faced in engaging American Indian mothers in an early childhood caries preventive trial. Int J Dent. 2015;2015:1–5. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/179189.

United States Census Bureau. American Community Survey. US Census Bureau. 2011. Available at https://www.census.gov/newsroom/releases/archives/american_community_survey_acs/cb12-175.html. Accessed 30 Aug 2020.

Viscogliosi C, et al. Importance of indigenous elders’ contributions to individual and community wellness: Results from a scoping review on social participation and intergenerational solidarity. Can J Public Health. 2020;111:667–81.

Weiner DK, et al. Functional reach: a marker of physical frailty. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1992;40:203–7.

Whitney JC, Lord SR, Close JC. Streamlining assessment and intervention in a falls clinic using the timed up and go test and physiological profile assessments. Age Aging. 2005;34(6):567–71.

Acknowledgements

I would like to extend gratitude to Kimberly Belock, OTR/L for her work in assisting to complete patient treatment and documentation of clinic participants. I would also like to extend gratitude to all direct-access providers in my facility who were willing to use the FLIP-Q and refer accordingly.

Authors' information

Kyle M. Knight (kmknight91@gmail.com) is a commissioned officer of the United States Public Health Service (USPHS) and is currently stationed at an Indian Health Service (IHS) facility. The opinions expressed in this article do not necessarily represent the views of the IHS, USPHS, or the institution with which the author has an affiliation.

About this supplement

This article has been published as part of Injury Epidemiology Volume 8 Supplement 2 2021: Highlights from the Inaugural National Conference on American Indian and Alaska Native IVP: Bridging Science, Practice, and Culture. The full contents of the supplement are available at https://injepijournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/supplements/volume-8-supplement-2.

Funding

No funding was received during the implementation of this clinic. Publication costs were funded by the Indian Health Service in conjunction with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KK created and implemented the clinic, analyzed the data, wrote and approved the final manuscript. The author read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all patients participating in the falls risk clinic for their data to be analyzed. There was no experimental or control group. This manuscript has been approved by the corresponding Institutional Review Board in which this clinic resides.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The author declares that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Knight, K.M. Implementation and initial evaluation of falls risk reduction resources in a rural Native American Community. Inj. Epidemiol. 8 (Suppl 2), 66 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40621-021-00359-1

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40621-021-00359-1