Abstract

Background

The learning assistant (LA) model supports student success in undergraduate science courses; however, variation in outcomes has led to a call for more work investigating how the LA model is implemented. In this research, we used cultural historical activity theory (CHAT) to characterize how three different instructors set up LA-facilitated classrooms and how LAs’ understanding and development of their practices was shaped by the classroom activity. CHAT is a sociocultural framework that provides a structured approach to studying complex activity systems directed toward specific objects. It conceptualizes change within these systems as expansive learning, in which experiencing a contradiction leads to internalization and critical self-reflection, and then externalization and a search for solutions and change.

Results

Through analyzing two semi-structured retrospective interviews from three professors and eleven LAs, we found that how the LA model was implemented differed based on STEM instructors’ pedagogical practices and goals. Each instructor leveraged LA-facilitated interactions to further learning and tasked LAs with emotionally supporting students to grapple with content and confusions in a safe environment; however, all three had different rules and divisions of labor that were influenced by their perspectives on learning and their objects for the class. For LAs, we found that they had multiple, sometimes conflicting, motives that can be described as either practical, what they described as their day-to-day job, or sense-making, how they made sense of the reason for their work. How these motives were integrated/separated or aligned/misaligned with the collective course object influenced LAs’ learning in practice through either a mechanism of consonance or contradiction. We found that each LA developed unique practices that reciprocally shaped and were shaped by the activity system in which they worked.

Conclusions

This study helps bridge the bodies of research that focus on outcomes from the LA model and LA learning and development by describing how LA learning mechanisms are shaped by their context. We also show that variation in the LA model can be described both by classroom objects and by LAs’ development in dialogue with those objects. This work can be used to start to develop a deeper understanding of how students, instructors, and LAs experience the LA model.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Introduction

The learning assistant (LA) model is a form of near-peer instruction in which undergraduate LAs facilitate student learning in classes that they have taken previously (Otero et al., 2006, 2010). Developed at the University of Colorado Boulder, the LA model has become widespread in active learning STEM classes, with 587 institutions currently involved in the LA Alliance, a community focused on improving undergraduate education through the implementation of LAs (LA Alliance, 2024). In addition to their practice in the STEM class, LAs also attend weekly preparation meetings with the instructional team and participate in a pedagogy course. These three components comprise the essential elements of the LA model, and they can be implemented flexibly to adapt to the local context. There is strong evidence that the implementation of LAs benefits student learning in STEM classes (Barrasso & Spilios, 2021), specifically students from marginalized groups (Sempértegui et al., 2022; Van Dusen & Nissen, 2020; Van Dusen et al., 2016). However, it has also been found that there are discrepancies in outcomes for different introductory STEM courses, which have been hypothesized to be connected to differences in implementation (Alzen et al., 2018). Thus, there has been a call for more work investigating how the LA model is implemented. In this paper, we shed light on how instructor goals lead to differences in how LA-facilitated interactions are integrated in introductory STEM lectures and how LAs develop their practice. This will make a first contribution to explaining variation in student outcomes from different implementations of the LA model by understanding how instructional choice shapes LAs’ motivations in interactions with students, and consequently student learning from those interactions.

In the following sections, we review what is known about LA learning and development through being LAs in general and how each of the three essential elements of the LA model relates to LAs’ practices and their learning before we turn to cultural historical activity theory (CHAT) (Engeström, 1999, 2001; Kaptelinin & Nardi, 2012) to guide our investigation of LA implementation in the context of different courses and LA learning in these contexts.

Literature review: learning assistants (LAs) and the essential elements of the LA model

Being an LA contributes to the personal and professional development of LAs. Through their work as LAs, LAs develop as teachers (Gray et al., 2016), advance in their STEM knowledge and epistemology (Cao et al., 2018; Lutz & Ríos, 2022; Otero et al., 2010; Price & Finkelstein, 2008), develop a stronger sense of STEM professional identity (Close et al., 2016; Conn et al., 2014; Nadelson & Finnegan, 2014), and improve their metacognition (Breland et al., 2023; Huvard et al., 2020). While these developments result from the interplay of LA learning through the pedagogy course, the instructional team meetings, and their practice in a STEM class, it is also important to understand for each essential element of the LA model how the element relates to the practices an LA engages in and what is known about learning through this element specifically.

The pedagogy course is the element of the LA model that introduces LAs to teaching and learning theory and thus grounds their practice theoretically. A common version of the LA pedagogy course introduces LAs to strategies that support four core ideas: (1) eliciting student ideas and supporting engagement of all group members, (2) listening to students and asking productive questions, (3) building relationships with students, and (4) integrating learning theories with effective practices (LA Alliance, 2024). However, there is great variation within the pedagogy course, depending on what is seen as most relevant for the context—for example, a pedagogy course for engineering LAs may focus on disciplinary-specific topics like design thinking (Quan et al., 2017). Research on LA learning in the pedagogy course has largely focused on their pedagogy course reflections and has found that LAs integrate different topics they learn about into their reflections and their practice, such as valuing student ideas or disrupting status imbalances (Auby & Koretsky, 2023; Koretsky, 2020; Top et al., 2018).

Preparation meetings include the learning assistants for a course, the faculty teaching the class, and any other team members involved in teaching the class such as graduate teaching assistants. In their meetings, the instructional team members reflect on previous classes and plan for future classes with respect to student expectations, what they observe about student learning processes, and disciplinary content (LA Alliance, 2024). During these meetings and more generally through their work together, LAs and faculty develop partnerships that can range from mentor–mentee relationships where faculty mostly mentor LAs for fulfilling their roles in class to collaborations where LAs are faculty consultants and co-design the class (Davenport et al., 2017; Hamerski et al., 2021; Hill et al., 2023; Hite et al., 2021; Indukuri & Quan, 2022; Jardine, 2019, 2020; Sabella & Roberts, 2023; Sabella et al., 2016).

Practice is the element of the LA model that describes the implementation of LAs in STEM classes to support student learning, i.e., what our study is concerned with. LAs’ practice can vary widely, where they may interact with students in classes of different sizes, such as large-lectures, small seminars, or discussion sections; work in lab settings; or be responsible for running their own study sessions and office hours in addition to their direct support in the classroom setting. A common factor is that their role is to support student learning, and not to be an evaluator or grader (LA Alliance, 2024). LA support contributes to student retention in STEM majors and a decrease in drop/fail/withdraw rates in STEM courses (Alzen et al., 2017, 2018), specifically for students from marginalized groups (Sempértegui et al., 2022; Van Dusen & Nissen, 2020). These course outcomes are connected to students’ improved conceptual understanding through LA support (Ferrari et al., 2023; Herrera et al., 2018; Miller et al., 2013; Otero et al., 2006, 2010; Sellami et al., 2017; Talbot et al., 2015; Van Dusen & Nissen, 2017; Van Dusen et al., 2015, 2016; White et al., 2016) as well as LAs’ positive impact on student satisfaction, engagement, and attitudes (Kiste et al., 2017; Schick, 2018; Talbot et al., 2015; Thompson & Garik, 2015; Westine et al., 2024). It is very clear that LAs not only help students with content learning but also increase students’ sense of belonging and disciplinary identity (Clements et al., 2022, 2023; Goertzen et al., 2013; Kornreich‐Leshem et al., 2022). In their practice, LAs create these positive impacts by taking on various roles in the classroom system and interacting with students in different ways. LAs create community, they serve as role models, they can gather important information for faculty to adjust instruction, and they interact with student groups on a much more regular and familiar basis than faculty (Clements et al., 2023; Hite et al., 2021; Jardine, 2019, 2020). Their interactions with students include interaction on the conceptual and the socioemotional level (Hernandez et al., 2021; Karch et al., 2024; Maggiore et al., 2024; Westine et al., 2024). When LAs facilitate student learning on the conceptual level, they focus on disciplinary ideas and interact with students either in more LA-centered ways often focused on canonical correctness or in more student-centered ways focused on student sense making (Bracho Perez & Coso Strong, 2023; Carlos et al., 2023; Karch & Caspari-Gnann, 2022; Knight et al., 2013, 2015; Maggiore et al., 2024; Pak et al., 2018; Stuopis, 2023; Stuopis & Wendell, 2023; Thompson, 2019; Thompson et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2023). On top of the conceptual level, LAs engage in socioemotional actions such as validating student ideas, bringing additional students into the conversation, and communicating norms and values of the class (Hernandez et al., 2021; Maggiore et al., 2024; Westine et al., 2024). While this recent body of research has provided needed understanding of LAs’ practices, we do not know how the nature of the STEM classes they work in influences and shapes LAs’ development of these practices.

To investigate the connection between the ways different STEM classes are set up and how LAs in these different contexts develop different ways of practicing what it means to be an LA, we look at variation within a single setting: large lectures where the LA’s role is primarily to interact with students during in-class active learning sessions. Our research is informed by CHAT, which helps us conceptualize the complex interplay of an LA’s practice within a larger classroom system and the learning that occurs through this interplay. CHAT is a sociocultural framework that provides a structured approach to studying complex systems, i.e., activity systems, and the processes of change and development that occur within these systems (Engeström, 1987, 2001). CHAT has previously been used to productively study topics such as learning assistants (Huvard et al., 2020; Talbot et al., 2016), the complex dynamics of classroom systems (e.g., Hurt et al., 2023; Patchen & Smithenry, 2014; Talbot et al., 2016) and how individuals within those system experience change and development (e.g., Caspari-Gnann & Sevian, 2022; Huvard et al., 2020; Keen & Sevian, 2022; Reinholz et al., 2021). By combining different theoretical constructs from CHAT, we can conceptualize the relationship between instructors’ goals, their classroom structure, and LA practice and development.

Theoretical framework: cultural historical activity theory

CHAT pays attention to work that occurs within sociocultural systems. In an activity system, human work toward a specific end is mediated by material and conceptual tools and shaped by socially situated rules, divisions of labor, and communities (Vygotsky, 1934/1987; Engeström, 1987, 2001). A key concept in CHAT is the notion of object. An object is what one is striving toward or working on within an activity system—the “ultimate reason” for the activity and what a subject is trying to achieve (Kaptelinin, 2005; Lazarou et al., 2017). According to some activity theorists, objects are primarily collective, and represent the thing being worked on and transformed into an outcome (Engeström, 1987; Kaptelinin, 2005); others use it to mean subjects’ true motive for an activity that arises from a need (Kaptelinin, 2005; Val Aalsvoort, 2004). These perspectives differ based on whether the unit of analysis is a collective system or individuals’ work within social systems (Cong-Lem, 2022; Kaptelinin, 2005). In this paper, we use both perspectives complementarily. To illustrate, consider a science classroom where an instructor (subject) may have the motive that they want students to sense-make, based on their need to teach students science and what they believe teaching science means. Thus, they design their collective classroom system to have the object of “sense-making.” Lessons integrate certain kinds of materials and problems (tools) that lead students toward sense-making rather than rote memorization and support this by following best practices for sense-making, such as encouraging groupwork (division of labor), not requiring students to have the right answer during class (rule), and having facilitators such as LAs and TAs interact with students during sense-making sessions (community). Engaging in sense-making (object) may lead students to have deeper understanding of disciplinary concepts (outcome). In this way, the motive sparks the object and the activity, the object directs how an activity system is set up, and the components of the activity system (tools, rules, divisions of labor) reciprocally shape how that object is achieved and what the outcome of the activity is.

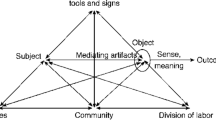

Because activity systems occur in complex environments, an object-oriented activity may also be shaped by interacting systems—what is referred to as third-generation activity theory (Engeström, 2001). A third-generation activity system consists of two interacting systems that may have partially shared objects and contradicting or aligning components. For example, the sense-making activity we described above may describe the activity system of an individual instructor’s classroom. However, their class may occur in a department that devalues sense-making and prefers instructors to stick to traditional testing and lectures, because the department is evaluated based on standardized test results. In this case, the activity system of the department has a different object (e.g., performance on an exam) and a different outcome (high test scores), which lead to it being supported by different tools, rules, and divisions of labor. At the same time, both the class and the department share an overarching object: learning science. Contradictions are not only experienced across activity systems but can also be experienced within a single activity system. These intra-system contradictions can be sources of change and development for actors within the systems and for structures themselves (Caspari-Gnann & Sevian, 2022; Engeström, 2001; Huvard et al., 2020; Keen & Sevian, 2022; Reinholz et al., 2021). Engeström (1999, 2001) describes this development as “expansive learning,” in which experiencing a contradiction leads to internalization and critical self-reflection, and then externalization and a search for solutions and change. This expansive learning then becomes integrated into and changes the activity system itself, for example, by creating new ways of working within the activity system such as new rules, tools, or actions (Caspari-Gnann & Sevian, 2022; Keen, 2021) or expanding the object of the activity (Engeström, 2001). With respect to LAs and other undergraduate mentor–teachers, Huvard and collaborators (2020) studied how contradictions led to expansive learning in LAs’ identity and metacognitive development. For example, many LAs experienced barriers and challenges that prevented them from being able to fulfill something they saw as part of their role—common challenges included contradictions between their division of labor around what they saw as their role and the conceptual tools they had available, such as familiarity with the content. To overcome these challenges, the LAs had to develop metacognitive awareness to identify the barriers and create new tools. This is an example of expansive learning and demonstrates how this can lead to growth of the individual (metacognition) and transformations of the activity (introducing new tools, redefining roles). Important to note is that CHAT is a “living theory,” which can be used flexibly and creatively to investigate and explore systems (Kaptelinin, 2005; Kaptelinin & Nardi, 2018). The predominant theory referred to as activity theory has changed over time, with three of the most commonly referenced generations being: Vygotskian sociocultural theory, which studied the role of mediation by tools and signs; Leontievian CHAT, which focused on individuals’ subjective experiences within an activity directed by motives; and Engeströmian CHAT, which focuses on activities as collective systems grounded in historical practices (Cong-Lem, 2022; Kaptelinin, 2005; Kaptelinin & Nardi, 2012). Each of these approaches has advantages and drawbacks: while Leontievian CHAT allows us to understand how an individual’s work within a social system is shaped by their motives and mediated by tools, it does not explicitly name the relevant pieces of the social system. Engeström’s CHAT makes those social aspects more explicit but has been critiqued for neglecting individuals’ transformation in favor of paying attention to the collective (Cong-Lem, 2022). These three approaches, which developed from each other, can be complementary (Kaptelinin & Nardi, 2012).

In our study, we are interested in understanding different ways the LA model can be implemented and how LAs learn to practice within different systems. We thus attend to two levels. First, the collective activity systems of three introductory, large lecture science courses that have active learning sessions facilitated by LAs, to understand differences in how instructors design and implement the LA model. Second, subjective experiences of individual LAs who experience change and development as a result of participating in those collective activity systems. Thus, we use different concepts from both Engeström and Leontiev as complementary approaches to explore our system at different levels. This theoretical work was developed in tandem with our detailed analysis, in which salient aspects of our findings were not sufficiently captured by a single version of CHAT but rather required different perspectives (see Fig. 1).

Representation of our use of CHAT in this study. The small group interactions (SG) are conceptualized as a neighboring activity excited by the motives of the LAs, which support and feed into the central activity of the LA-facilitated whole course (WC). Here the neighboring activity is pictured as a tool-producing activity; however, our analysis is not limited to this single kind of connection

To characterize the collective activity systems of LA-supported classes and to make them comparable, we use third-generation activity theory. Based on our analysis, we found it was most fruitful to describe the LA-supported class through the concepts of central and neighboring activities (Engeström, 1987). Neighbor activities provide and shape components of the central activity. In our analysis, LA-facilitated small group discussions (SG) served as neighboring activities, which fed into and supported the central activity, which is the whole class (WC) as planned and facilitated by the professor (Fig. 1). For example, the SG produced tools for the central activity, but also consisted of communities governed by distinct rules and divisions of labor. The concepts of neighboring and central activities allow us to understand both what specifically happens in activities where the LA is a key subject (the neighboring activity), as well as how that activity is leveraged by the professor (the central activity), while acknowledging that these systems are deeply related and not separate.

To characterize LAs’ learning in practice, we use Leontievian and Engeströmian CHAT as complementary approaches. We understand learning in practice as LAs’ process of learning through engaging in classroom facilitation. We investigate LAs’ learning in practice to understand how their learning about what it means to be an LA and how they carry out that role shapes and is reciprocally shaped by the activity system in which they work. To do so, we pay attention to how LAs in different contexts develop different ways of practicing what it means to be an LA; how LAs conceptualize their motives for the activity systems they participate in and how this conceptualization differs from or align with how professors conceptualize the activity system; and how these differences and alignments lead to LAs experiencing contradictions and expansive learning. To do so, we draw on concepts from both Engeströmian and Leontievian activity theory, to understand how LAs’ engagement in the collective activity and what contradictions may result from that engagement (Engeström, 1987), as well as LAs’ motives that initiate how they engage with the collective object (Van Aalsvoort, 2004). Following Kaptelinin’s (2005) work on Leontievian CHAT, we specifically conceptualize LAs’ practice as multi-motivational (Fig. 1). According to Kaptelinin, activities can be shaped by multiple motives—for LAs, for example, this could be “helping students learn science” and “getting paid.” These motives are directed toward a singular object, which “gives the activity structure and direction, […and which] is cooperatively determined by all effective motives” (Kaptelinin, 2005, p. 17). Their learning in practice and engagement in the collective activity is structured by how they negotiate and reconcile their multiple motives and consequent practice within the larger social context.

To explore these complexities, we pose two research questions:

-

RQ1. How are LA-facilitated interactions integrated into introductory STEM lectures, and how is this integration mediated by LAs?

-

RQ2. How do LAs understand and negotiate different motives for their practice, and how does this lead to their learning in practice?

Methodology

Multiple case study design

We followed an embedded multiple case study design (Yin, 2018). Each case was a single classroom that utilized the LA model (focus of RQ1). The embedded subunits were individual learning assistants (focus of RQ2). The three case study classrooms for our study were drawn from a larger data corpus that encompassed 4 semesters worth of data (fall 2020—spring 2022) collected from 12 introductory chemistry and physics courses at two institutions. 5 of these classes were taught in-person, 6 were taught remotely, and 1 was a synchronous hybrid course. In prior studies, we used data from this larger corpus to study LA facilitation practices, student in-the-moment learning in LA-facilitated courses, and the impact of LA facilitation on student in-the-moment learning (Carlos et al., 2023; Karch et al., 2024; Maggiore et al., 2024).

The case study classes were selected based on two criteria: first, we selected in-person rather than virtual courses, because the virtual courses we collected data from were taught during emergency COVID remote instruction and may be less generally applicable to the LA community. Second, we selected courses where the professor had previously taught with learning assistants for at least one semester and had previously taught the class in question. We did this because these instructors’ practices with regards to LAs had stabilized more than others in our data corpus who were learning to teach with LAs for the first time. This led to three classes being eligible for inclusion in the study at hand. These three cases were representative of our data collection context, which included two institutions and two disciplinary contexts, i.e., chemistry and physics. They also represented the range of ways instructors ran their courses, from primarily lecturing with intermittent problem-solving sessions to primarily problem-solving with very little or no formal lecturing.

Description of cases

All three cases were introductory, large enrollment undergraduate STEM courses that utilized active learning and primarily served non-major students. In addition, all courses had other LAs and/or graduate TAs who did not participate in the study. To avoid identifying our participants, demographic information is not shared.

Chemistry A, taught by Prof. Beaker, was a General Chemistry 2 (GC2) class in fall 2021 at a highly diverse public R2 institution in the northeastern United States with approximately 175 students and 2 participating LAs. Prof. Beaker taught with Chemical Thinking, a reformed curriculum that emphasizes developing chemistry ways of thinking over memorizing and applying facts and equations (Talanquer & Pollard, 2010). In addition, we drew insights from interviews during a second semester of data collection for Prof. Beaker (GC 1 in Spring 2022), also taught with Chemical Thinking. Prof. Beaker taught with a semi-flipped model, where approximately 2/3 of class time was dedicated to delivering content and 1/3 was dedicated to problem solving. While students were asked to read Chemical Thinking as an interactive, online textbook before coming to class, Prof. Beaker made sure to not rely on student reading alone but also deliver the content in a lecture format.

Chemistry B, taught by Prof. Lemur, was a GC2 class in fall 2021 taught at an R1, predominantly white private institution in the northeastern United States with approximately 135 students and 5 participating LAs. Prof. Lemur also taught with Chemical Thinking and additionally placed an emphasis on what she called equitable chemical practices, for example, asking students explicitly to consider different alternatives within a problem space brought in by different student group members. Prof. Lemur taught with a primarily flipped model, where the majority of class time was dedicated to problem solving (within groups and as a whole class), and students were expected to read Chemical Thinking as an interactive, online textbook before coming to class.

Physics, taught by Prof. Vishnu, was a Physics 1 class taught at the same institution as Chemistry B. Data were collected from 2 sections of this course, which were collapsed into one for the sake of data analysis, as they were set up and taught in the same way. Each section served approximately 90 students, and 2 LAs per section participated in the study. Although Prof. Vishnu did not use a particular reformed curriculum, his instructional model was based on responsive teaching (Hammer et al., 2012). Prof. Vishnu also taught with a primarily flipped model.

Data sources and recruitment

Several forms of data were triangulated for this embedded multiple case study (Yin, 2018). Data were collected three times per semester. During data collection, LAs wore body harnesses and recorded interactions with consented students from their own perspectives using their cell phone cameras. We video recorded the entire class using standard classroom recording technology, e.g., Echo360 or Zoom (depending on the professor’s preference). The first author attended all data collections and took informal field notes about salient events during class, as well as debriefed with all LAs and instructors after each class. After each data collection, all LAs, the professor, and a select number of student groups participated in semi-structured video-stimulated recall interviews that lasted no longer than 90 min. The first author provided the interview team (undergraduate and graduate research assistants, including the second author) with relevant field notes, so they could follow up on specific salient moments in addition to the standard interview protocol. In addition, we gathered instructional artifacts such as the instructors’ slides and/or lecture notes after each class.

The primary data source used for analysis were the professor and LA interviews. During interviews, participants watched up to three clips of small-group interactions they had been involved in (or in the case of the instructor, de-identified clips from selected LAs, such that they saw each LA at least once over the semester). They then answered a series of questions probing what happened, e.g., what they thought students learned, expectations for the interaction, and the rules that governed what they or others in the class were and were not allowed to do (see Table 1 for the professor protocol; the LA protocol was previously published in Carlos et al., 2023). Professors also watched clips of the whole class immediately following each small group interaction and were asked about how the two clips related to each other.

To recruit participating instructors, we sent invitations to all instructors teaching with LAs in the two institutions. To recruit LAs, we worked with the instructors to identify LAs who would be good candidates for participation in the study and sent them email invitations. Each participating LA was offered a $500 stipend. To recruit students, we announced the study in lecture and via their course management system. For participating in the study, students received either a $10 stipend or a small amount of extra credit, maximum 2% of their final course grade. These stipends, which were budgeted into the project’s NSF grant, not only served as an incentive and an expression of gratitude for their time, but also helped emphasize how serious the commitment was. Participating LAs recorded interactions on their own phones and needed to delete them as soon as they were transferred to the research team; being paid a significant amount for taking over this responsibility incentivized compliance with IRB regulations. All data have been de-identified and are presented with pseudonyms. IRB approval was received at both participating institutions.

Data analysis

Our analysis focused on activities from two perspectives: characterizing the collective classroom activity system, in which multiple subjects worked toward an object and were governed by different rules and divisions of labor and which included both neighboring and central activities (Engeström, 1987); and uncovering individual subjects’ understandings of the neighboring and central activity, which was mediated by their position within the classroom, their prior histories, and which could contradict with the collective activity (Carvalho et al., 2015; Kaptelinin, 2005). Thus, in our analysis, to develop the collective systems that describe each classroom case, we first developed individual systems that addressed each individual’s experience of the activity (see Fig. 2 for flow chart of analysis).

To characterize the activity system from each participant’s point of view, we followed a multi-stage procedure. In stage 1, we analyzed 2 out of 3 interviews for all LAs (n = 11) and professors (n = 3), in order to maximize diversity of experiences amongst the dataset while balancing both feasibility of analysis and what was needed for saturation. The interviews were selected based on density of information (evaluated from field notes) and representativeness of the participants’ practice. We prioritized interviews from later in the semester when participants’ practice had stabilized. Insights from the interview we did not formally analyze were used to support interpretation of the codes.

We analyzed each interview in NVivo using directed content analysis (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005; Patchen & Smithenry, 2014). Each code we developed captured three pieces of information: (1) the CHAT component (e.g., subject, tool, etc.), (2) which activity the code belonged to (the neighboring small group—SG— or central whole class—WC—activity), and (3) an inductive description of the code. An example of one such code is “Division of Labor (DoL) SG-LA’s role is to encourage students to work together.” After first-level coding for both interviews, we used NVivo to combine similar codes to reduce the total number of codes and to identify commonalities across both transcripts. An example of a combined code is “Tool SG- different ideas that they can build on, including from outside of class and that may or may not be relevant,” which was developed from consolidating “Tool SG- content knowledge that may or may not be relevant” AND “Tool SG- different ideas that they can build on.”

In Stage 2, we constructed individuals’ perspectives of the activity systems using coding tables. During coding, we found that individual subjects sometimes described multiple, conflicting motives that would be supported by different rules or divisions of labor. To capture these nuances, the coding tables were organized around each motive we identified for a participant and the components that mediated each motive, some of which were the same across motives and some of which were different. These tables were organized, such that a row corresponded to a motive, and each column was a different CHAT component (tools, rules, division of labor, outcome) that supported that motive.

To identify which components belonged to which motives, we read the coded interview transcripts in NVivo using the coding stripes feature. We read the interview from top to bottom, populating the coding table with codes from the coding stripes. Participants often brought up several CHAT components, either within the same utterance, or within proximity to each other in the conversation while discussing the same phenomenon (e.g., there were sections of the transcript that were double or triple coded). This was evidence that the participant saw these ideas as related to each other. Thus, we organized them within the same row of the table. In addition, if the participant later discussed one of these components in relation to different ideas, we decided whether they belonged to the same motive (same row), a different motive (different row), or both, relying on the context of the conversation. As the conversation went on, we continued to add to these rows as the participant expanded on their thinking. We then analyzed the participant’s second transcript in the same way, adding additional codes to the same coding table. The product of this process was two coding tables for each participant, one that represented their experience of the neighboring SG activity system and one that represented their experience of the central WC activity system, each of which included multiple motives and the various rules, divisions of labor, communities, and tools that mediated their work toward these motives and the outcomes of each object-related activity. When an interaction was coded by multiple people (see trustworthiness procedures below), each person compared their own coding tables and discussed them to consensus. The tables characterizing the individual LAs’ perspectives on their activity, and the contradictions that resulted when we looked across rows, were key for our interpretations toward RQ2.

Finally, we constructed the class-level activity systems, which focused on the class as designed. For these, we relied on the analysis of the professor interviews as our primary data source, supported by the LA interviews as members of the instructional team.

For the professors, we did a third stage of analysis. We transformed each coding table into a narrative thick description that captured each professor’s perspective on their class and the tensions and contradictions they navigated in their practice (Ponterotto, 2006). These narratives helped us understand the collective activity in practice by contextualizing the activity theory components. Each narrative had three sections, focusing on the neighboring system, the central system, and how neighboring activities were integrated into the central activity. These narratives were key for our interpretations toward RQ1.

In addition to the interviews, we triangulated other forms of data for our interpretations toward RQ1 and RQ2 (Yin, 2018). These data included recordings of small group interactions and whole class discussion, instructors’ slides and/or lecture notes, informal observation notes taken during class or debrief sessions with the instructional team that noted salient moments to follow up on during interviews, researcher memos, semi-structured video-stimulated recall interviews with the student groups, member checking discussions with the professors (described below), and other semesters of data collection from the same instructors. Although these were not part of our formal analysis, these other forms of data helped us become immersed within the context of a classroom to gain a more holistic understanding of each case.

Trustworthiness and consensus processes

We had three main mechanisms for establishing trustworthiness: researcher reflexivity facilitated through our research team’s multiple forms of membership; collaborative coding; and member checking (Creswell & Miller, 2000).

With regard to multiple forms of membership, each author brought insider–outsider positionalities that influenced their interpretation of the data, and which allowed us to iterate between theory and practice. JMK (Author 1) is a postdoctoral scholar, who led the interview team and previously taught with LAs. They had a personal relationship with all the professor participants that laid a foundation of trust during interviews and brought an epistemological perspective closer to those of the instructor participants when analyzing data. SM (Author 2) was an undergraduate researcher who had also been a student in previous iterations of two of the case study classrooms and had participated in the research study as a student participant prior to joining the research team. She conducted interviews with students and LAs and worked as an LA while engaged with data analysis. In analysis, she brought a deep insider perspective and her own lived experience that she leveraged to interpret student and LA experiences and motivations. MPK (Author 3) was an undergraduate researcher who conducted professor, LA, and student interviews during previous iterations of the case study. He also engaged in data analysis and conceptualization of the study. In analysis, he worked closely with activity theory and brought perspectives from his training in both physics and community health to bring multiple disciplinary perspectives to the data and leveraged his student status to attend closely to the particularities of participants’ lived experiences. His interview memos about Prof. Vishnu’s practice from earlier data collection periods were used to shape the interview protocol for the case study semester. ICG (corresponding author) is a faculty member who teaches with learning assistants. To not risk disclosing the identity of any of the research participants, we refrain from giving more details about her positionality. These different perspectives meant that we had different affinities toward and interpretations of the data.

Reconciling these positionalities and interpretations played out in two ways. First, we did collaborative coding on a large portion of our data, particularly in early stages. JMK and SM extensively discussed their interpretation of all three professors and 1 LA per class and collaboratively constructed narratives. This was additionally supported by triangulation with SM’s analysis of one student interview per class for her independent study. JMK then took these discussions to analyze the rest of the LAs independently, and then collaboratively coded 4 of them with ICG. This formal collaborative coding, and ongoing discussions and negotiations of perspectives, helped us stay closer to the participants’ original intention by bringing together multiple lenses on their practice. Specifically, the undergraduate authors’ perspectives, which were closer to the student and LA perspectives, helped the more senior authors check their assumptions about what types of activity were valuable within the system and to ensure that we were not taking the professors’ perspectives as the “ultimate truth,” but rather privileging student and LA experiences within the collective system at the same level.

Finally, we engaged in formal and informal member checking with the professor participants. For the formal member checking process, we sent each professor two documents: their narrative summary, and a document with excerpts from interviews with their LA[s]. For the narrative, we asked if our summary accurately captured their experience. Two of the professors agreed entirely with our interpretations. For the third professor, this process taught us more about the relative importance and connections of different components of his activity system, and we adjusted his narrative accordingly. For the LA excerpts, we asked how what the LA described in their interview aligns with their expectations, where they thought the LA may have learned that, whether there was anything surprising, and whether the LA “went beyond” what they expected or taught them to do. This helped us understand in what ways the LA’s practice was unique compared to what they were taught to do by the instructor. Since contradictions between LA motives and the collective activity system were much easier to identify, we specifically selected excerpts from LA interviews that we thought aligned with the professor’s understanding of the collective activity system to understand whether these represented unique components (e.g., evidence of expansive learning through changing the activity system) or not. The instructors’ comments were then integrated as data sources to support our analysis. For the informal member checking process, Prof. Vishnu and Prof. Lemur both participated in several coding meetings over the period of one year, where they weighed in with their interpretations of the data. These were integrated into our interpretations of the data as well as the development of our coding scheme.

Findings

The goal of this study was to explore different ways the LA model is implemented, and how operating within these activity systems shapes LAs’ learning in practice. We found that a careful analysis of the differences between different LA-facilitated courses was crucial to understand how LAs learned during their practice. We have three major findings: (1) how instructors integrate LA-facilitated interactions in introductory STEM courses varies greatly and depends on what they see as the reason for their class, i.e., the central activity’s object; (2) LAs often have multiple motives for their SG interactions, one related to the central activity and one related to their prior histories, and these can be integrated or separated and can align or misalign with the objects of the collective activity; and (3) this integration/separation and alignment/misalignment can lead to LAs learning through mechanisms of either contradiction or consonance.

Integration of LA-facilitated interactions in introductory STEM courses

Our first research question sought to understand diversity in the ways the LA model is implemented by attending to how LA-facilitated interactions are integrated into introductory large-lecture STEM courses, and in what ways (if any) LAs mediate how these neighboring activities are integrated into the central activity. These activity systems are deeply complex, with many rules that govern different aspects of student–instructor interactions, and different roles students and LAs play. The following findings section summarizes the most salient aspects of the three cases’ activity systems, and then compares them to characterize more general aspects of the LA model.

In Chemistry A, (see Fig. 3) Prof. Beaker saw LA-facilitated SG interactions as opportunities for students to “discover for themselves and think about [chemical concepts] for themselves” (Prof. Beaker) in a safe learning environment that would bolster their confidence with chemistry. This object was supported by the dual roles of the LAs in these interactions, which were to push students to think in the canonically correct direction while simultaneously emotionally supporting students to stay engaged even when they feel frustrated. When doing so, LAs experienced a tension between contradicting rules that they should be present when students need help and that “hovering over their shoulder […] make[s] the students feel awkward” (LA Mango). LAs Shruthi and Mango had different approaches to deal with this contradiction, sometimes sitting in one spot and letting students come to them, sometimes only approaching groups when called over, and sometimes actively seeking out students who look confused. The important rule for LA–student interactions was that LAs should be led by what the students needed most support in and support them as content experts. This was mediated by the relationships LAs had formed with students; LAs ran study sessions for students outside of class time, and typically the same students would go to the same LAs’ study session. These relationships often carried over to class and influenced which students sought out which LAs. Prof. Beaker especially valued when LAs guided students toward thinking about the problem and developing stronger content knowledge, without providing a direct explanation or giving them the answer.

Collective activity system (SG on the left, WC on the right) in Prof. Beaker’s class. The brown curved arrow represents how the SG serves as a tool-producing activity for the WC. The straight brown and blue arrows represent how the SG (brown) and WC (blue) contribute toward the same overarching outcome

When leading class after small group discussions, Prof. Beaker built on the work students had done in thinking through the concepts and debriefed the class on the correct answer, in line with his stated role as the one responsible for overseeing the material. Typically, this role was enacted as a lecture, where he delivered a pre-planned explanation. Sometimes, if he heard similar confusions from enough students as he was circling around during the SG discussions, he addressed those questions or solicited additional questions from students. During this phase, LAs were allowed to use their best judgement to continue individual conversations with students, if they believed that would be more helpful for that individual student—a role that aligned with their work during the neighboring SG activity. Ultimately, Prof. Beaker wanted to ensure that students understood the concepts as best as possible, and so he preferred the LAs to keep explaining to the students if they had a better understanding of what that specific student’s confusion was. In this way, small group interaction served as a preparatory period in which students got their specific questions answered by the LA, so that they could better pay attention and match what they understood to the professor’s demonstrated solution, in order to develop their chemical content understanding—e.g., the neighboring activity was a tool-producing activity. Both the neighboring and central activities were guided by objects intended to help students develop understanding of chemical concepts.

In Chemistry B, (Fig. 4) Prof. Lemur saw SG interactions as an opportunity for students to refine their own thinking, which they could bring to the WC, when multiple groups reported out their ideas. LAs stayed with a group during the entire SG period, and their role was to help ensure the students had high quality conversations about the content and to help make connections between different students’ reasoning. The LAs were explicitly coached by Prof. Lemur not to direct the students toward the “correct” answer as they were not allowed to impose their thinking on students. Prof. Lemur was worried that this would take away students’ agency in their learning and lead them to internalize that SG interactions were about solving the problem rather than collaborative sense making. Instead, the professor designed the problems such that there were extra questions or pieces of information on the slide, to serve as a proxy for the professor’s authority and give the LAs and students something to refer to. This was meant to mitigate the LAs feeling like they needed to act as a content authority in the moment of interaction by giving them an anchor they could refer to. In addition, LAs and students worked in mostly the same groups all semester, and LAs attended to the groups’ social dynamics and helped foster equitable interactions between students.

During the WC following small group interactions, Prof. Lemur rephrased the ideas students shared out not only to make sure she and the rest of the class understood them, but also to make core parts of student thinking more explicit, often with drawings and through comparisons to her own thinking. She sometimes directed the flow of the conversation by strategically calling on students who she thought would contribute diverse ways of thinking including but not limited to the correct perspective. This allowed her to simultaneously develop the canonically correct solution using student ideas while eliciting and comparing student diverse ways of thinking, which also enabled students to participate in a larger community during WC and hear ideas beyond their small discussion groups. In this way, the SG was tool-producing for the WC. She also saw the relationship between SG and WC as reciprocal, as she believed the WC guided what happened in the SG interactions over the course of the semester. For example, during discussions in WC, Prof. Lemur modeled how to consider and “give justice to different thoughts” (Prof. Lemur). This modeling then influenced how students interacted with and considered others’ ideas in SG—i.e., the central activity also provided tools for use in the neighboring activity. Interestingly, Prof. Lemur did not do this modeling intentionally—she only realized it was influencing students’ practices after watching videos of student interactions during her interviews as part of this study. One LA (Ayaoba), however, did perceive this as modeling and enacted it in her own practice intentionally, which will be discussed in more detail in the following section.

In Physics, (Fig. 5) Prof. Vishnu saw the SG and the WC as deeply intertwined, directed toward the same overarching object of developing scientific practices which would help students shift their idea about what it means to do science away from memorization of content. The SG interactions served as a space for the students to grapple with confusions in a safe and comfortable environment; establish continuity across different problems and scenarios; and grapple with the practices of science, with content-specific objectives present but secondary. He saw grappling with the practices of science as important for students to advance their understanding of content and was more interested in how students progressed their understanding through confusions and sense making than in ensuring students always got the right answer. Similar to Chemistry B, the LAs’ primary role during SG was to help facilitate discussion, including jumpstarting it when it died down and attending to students’ social dynamics and emotions. They also enforced the object of the central activity by reframing confusions to be a positive experience and helping students grapple with confusions productively. Students worked with the same group and LA for the whole semester, so they could get to know each other, build relationships, and establish distinct and trusting communities within the SG.

Professor Vishnu’s activity system (SG on the left, WC on the right). The brown curved arrow represents how the SG served as a tool-producing activity for the WC. The straight blue and brown arrows show how the SG and WC have a shared object, developing practices of science that leads to a shared outcome

Student ideas developed as outcomes of these interactions were the primary tools in the WC. Prof. Vishnu saw his role while debriefing collectively to “sort of coordinate what the students are saying as a whole and allow that to shape the learning experience and learning environment” (Prof Vishnu). He often felt challenged by the work of coordinating and making sense of student ideas and worried about “cherry-picking” ideas to develop a story consistent with his way of thinking, because he saw student ideas that were inconsistent with the canon as learning opportunities. This aligned with the objects for both the central and neighboring activities, which were primarily to develop scientific practices. To support this in the WC, he tried to encourage students emotionally by validating and normalizing progress and changes in thinking. LAs played a background role in the WC by encouraging students (during their SG discussion) to develop and share out their ideas, tracking who participated and through what modality (e.g., vocally or through a digital polling platform), and debriefing after class about how student participation during the WC went. In this way, the SG served as a tool-producing activity for the WC.

The LAs in all three courses played two core roles to mediate the integration of the neighboring small group activity into the central activity, which were enacted differently based on the dynamics and priorities of the rest of the activity system. First, they emotionally supported students to grapple with content and confusions in a safe environment. In Prof. Beaker’s class, the LAs did so by providing a sense of safety through their presence, e.g., so that the students could rely on the LA to direct them as they navigated new understandings. They also did so by respecting students’ space, only entering conversations when they were needed. This aligned with the central activity’s object of supporting students’ individual needs and learning trajectories. In Prof. Lemur’s and Prof. Vishnu’s classes, the LAs did so primarily by supporting the student groups to work together in an equitable way, to make sure that feeling of safety came from within the students’ groups. This aligned with the broader goals of developing epistemic agency within a group. Second, the LAs supported the students to feel prepared for learning in the whole class. In Prof. Beaker’s class, the LAs did so by helping the students resolve their confusions, so they could better follow along with Prof. Beaker’s explanation and not feel lost as class went on. The LAs also did so by answering students’ questions one-on-one during professor explanations in the whole class, if they thought that their explanation would help the students grasp the content better than the professor’s explanation. In Prof. Lemur’s and Prof. Vishnu’s classes, the LAs supported learning by helping students to refine their ideas and gain confidence to participate during whole class discussions. LAs were encouraged to share out ideas they heard from their student groups to contribute to the collective whole class discussion.

Ultimately, we found that the rules that governed the activity system, and in particular the LA’s role and moves within the activity system, were deeply related to the instructor’s priorities and perspectives on learning. What the instructor valued, how they modeled interacting with students, and how they coached LAs to interact with students shaped how the LAs worked in each space. For each class, the LAs' primary role was to support students. However, what that meant and how LAs achieved their role differed depending on the features of each class.

Practical and sense-making motives: how do LAs understand their role?

Our second research question asked how LAs understand and negotiate different motives for their practice. In this section of the findings, we will attend to LAs’ motives and how they related to the class activity system LAs worked in before we turn to LA learning in practice in the final section.

An analysis of motives arose out of a conflict we found in the data. When we tried to analyze for object, we had difficulty identifying one singular “true reason” for the activity from the LAs’ perspectives. Rather, they often had multiple motives for their activities, which were sparked by different needs. Most commonly, we found LAs had two motives: practical motives, i.e., what the LAs’ saw as their day-to-day activity and which were sparked by the need to do the work set out by their supervising instructor; and sense-making motives, i.e., what they saw as the underlying motivation for the activity and which were sparked by their own deeply held beliefs about learning developed throughout their schooling. Practical motives included facilitating discussion or helping students solve problems and were often supported with explicitly communicated classroom rules and divisions of labor. Sense-making motives, on the other hand, were motivated by how the LAs made sense of their classroom activity and what the students were getting out of it, such as developing conceptual understanding, and were supported by rules communicated by the instructor, participation in the neighboring activity of their pedagogy course, and by their prior experience. In Table 2, we show the primary practical and sense-making motive for each LA, organized by course the LA worked in.

We found that LAs’ practical motives were more similar within a single class than they were across classes. This aligns with our findings from RQ1, that instructors with different collective classroom objects and pedagogical orientations have different conceptions about how LAs should embody and enact their role. For example, Prof. Vishnu strongly emphasized that the purpose of in-class discussions was to have students productively discuss their sense making, share confusions, and develop scientific practices. The LAs in this class, consequently, saw the neighboring activity they were engaged in as fostering collective and productive discussion and the sharing of thoughts, with a motive that reflected that. For LAs in Prof. Beaker’s class, where SG discussions were meant to help students think about chemical concepts on their own and identify where they may have gaps in their understanding, LAs’ primary practical motive was helping students solve problems. In Prof. Lemur’s course, which focused strongly on both developing conceptual understanding and discussion, LAs had differing practical motives, where some LAs emphasized applying reasoning in a new context (more problem-centered) while others emphasized sharing and listening to each other’s thoughts and confusions (more discussion-centered). This suggests that the rules of an activity system strongly shape the practice of an LA, and that their practical motives may arise from the need to “do their job” and follow what the professor directs them to do—i.e., it is shaped by the central classroom activity and the collective object for the neighboring activity as directed by the instructor.

In contrast, there were more similarities than differences in LAs’ sense-making motives across classes. Many LAs’ sense-making motive was for students to develop conceptual understanding, which typically meant students’ progression toward a canonically correct understanding in the moment of the SG. This applied even in classes with collective objects that deprioritized the scientific canon. This suggests that even while LAs strived to do the job the professor told them to do, they did not necessarily have the same underlying understanding of what made that job meaningful, and what types of skills and capacities it was directed toward developing. This may suggest that their understanding is shaped by their engagement in other activity systems, such as their socialization within the norms of STEM culture in the classes they take as students.

To understand how the dynamics of these competing motives played out, we attended to how practical and sense-making motives intersected and how they interacted with the activity’s collective object. We found that for a single LA, their practical and sense-making motives could (1) be integrated with or separated from each other and (2) could be aligned or misaligned with the collective object. The degree of integration or separation of motives could be observed analytically in whether the LA was drawing close connections between the practical and sense-making motives or not and whether these two motives were supported by the same or different CHAT components (e.g., rules). We found that LAs who had integrated motives also tended to have sense-making motives that were well-aligned with the object of the collective activity, while LAs who had separated motives also tended to have sense-making motives that were misaligned with the object of the collective activity. To illustrate how this played out, we will compare two LAs from Prof. Vishnu’s class: LA Capen and LA Shin.

LA Capen had highly integrated motives that were supported by much of the same activity components. Her practical motive of discussing thought processes collectively and her sense-making motive of student sense-making were both oriented toward the idea that discussing ideas was valuable per se. Her deep alignment with the collective activity’s object of grappling with practices of science in a safe environment came not just through her motives, but also through the components that supported her understanding of the neighboring activity system. For example, many of her rules and divisions of labor focused on attending to group dynamics and fostering groups with trusting relationships where students can be “vulnerable,” i.e., fostering a safe environment for student sense-making. Her outcomes also integrate Vishnu’s ideas of practices of science: she saw the outcome of the small groups not just as solidified thinking, but also as learning to ask questions, being okay with being confused, and seeing and disagreeing respectfully with each other’s ideas, i.e., progression in scientific practices.

On the other hand, LA Shin, like many other LAs in our dataset, had separated practical and sense-making motives that were supported by different and sometimes even conflicting rules. His practical motive that students should discuss collectively as a group to understand each other’s reasoning was supported by the division of labor that students share perspectives and articulate their thoughts, and that the LA facilitates sharing perspectives and nourishes discussion. This aligned well with how Prof. Vishnu spoke about the LAs’ job and how he valued multiplicity and equity of ideas. However, when Shin discussed his sense-making motive of learning fundamental physics ideas, he framed it as something that was done by applying knowledge from pre-lecture to the problem at hand—a view of the activity that differed from the object of the collective activity. This and the components that supported it revealed that he saw the value of different ideas not in the ideas or sense making per se, but rather in their proximity to canon. LAs in Prof. Vishnu’s class were not allowed to give students the answer or to enforce canonical correctness during SG discussion. Shin sidestepped this rule by creating a division of labor where he positioned students with more correct understanding to explain and teach others in their group, rather than teaching them himself. This allowed him to achieve his sense-making motive without explicitly violating classroom rules, because he was not enforcing canonical ideas, the students were.

Interestingly, both Capen and Shin reported that their sense-making motives aligned with Prof. Vishnu’s perspective, even though Shin and Prof. Vishnu had conflicting rules and underlying personal motivations and understandings of the activity. Shin was in his second semester of working as an LA for Prof. Vishnu; that this disconnect persisted may suggest that it stemmed not from a lack of communication, but rather from the way Shin made sense of and justified the work the class was doing to make it internally coherent with his own value system. Capen’s value system, on the other hand, may have already been more aligned with Prof. Vishnu’s teaching and pedagogy, and thus was able to form more coherent motives that excited her practice—in fact, during our member checking, Vishnu commented that it went beyond his ideas in some way:

And picking up on your question: are there things here [Capen] is saying distinct from my view, while still in alignment. To me, definitely everything is in alignment with my view of the purpose of small group activity. […] But, now that I think about it—I have not explicitly connected progress to progress in enacting practices. It’s usually conceptual progress that I’ve explicitly referred to. So [Capen] may be picking up on something I have not emphasized. Certainly I believe there is progress to be made in enactments, but I don’t usually foreground it. It’s more like I say: “understanding” has progressed; I don’t usually say “practices” have progressed.

Here, we see evidence that both Capen and Shin created aspects of their practice that were unique from Vishnu’s, and that this creation was related to how they reconciled their sense-making and practical motives. Capen created her outcomes from [an implicit] alignment; Shin created his division of labor from [an implicit] contradiction. These two findings help us identify two mechanisms of LA learning-in-practice: contradiction and consonance.

LAs’ learning-in-practice: mechanisms of consonance and contradiction

To demonstrate the mechanisms of learning through contradiction and consonance in more detail, we will use two LAs from Prof. Lemur’s class to discuss how these LAs negotiated contradicting and aligning motives, and how this negotiation led to their expansive learning in practice.

Because Prof. Lemur deprioritized canonical correctness in her lecture, especially during the SG, some LAs experienced a contradiction with their prior experience as STEM students that showed them that getting the correct answer is crucial for content learning. One such LA was Cosog. His sense-making motive was developing conceptual understanding, because he felt that an important part of learning chemistry was to eventually reconcile your understanding with the canonical solution. However, he did not enforce this or direct students in SG, because this was against the collective rules of the SG and he had learned in his pedagogy class that it was better for student learning if LAs did not give the right answer during small group discussion. Thus, in the externalization of his sense-making motive, he developed a personal rule. Although he was not allowed to answer questions directly in SG, because SG was explicitly not about the canonical solution, he did see the central activity primarily as developing the canonical solution. Thus, his rule was that once the instructor said the answer while debriefing students, he was allowed to directly answer student questions; he did not have to abide by the roles and rules for the SG while in the WC, because his sense-making motive was shaped by his understanding of the central activity’s object. Here, Cosog underwent an expansive cycle driven by contradiction; he externalized actions that helped him gain coherence with his own understanding of the system.

In contrast to LA Cosog, LA Ayaoba’s understanding of the activity was more aligned with the collective activity for the small group discussions. Similar to Capen, she sometimes went beyond what the professor intended the LAs to do. LA Ayaoba’s sense-making motive was for students to refine their own chemical thinking collaboratively, and this was highly integrated with her practical motive of having students share and listen to each other’s confusions. Both motives aligned with the neighboring activity’s collective object of refining chemical thinking. To enact this object, she developed unique practices to support students’ chemical thinking. For example, she initiated cycles of clarification, where she listened to a student’s thought, and then asked a different student to reflect that thought back to make sure all students had understood it similarly. This clarification cycle was supported by the practical rule that all students should hear each other and have a chance to speak, as well as the sense-making rule that all students should engage in a collective conceptual clarification process between what they are sharing and receiving from each other’s chemical thinking. Ayaoba invented this conceptual clarification move as a way of enacting the collective object and supporting students to refine their own chemical thinking. Another piece of evidence for her alignment is that Ayaoba recognized Lemur’s implicit modeling during the WC, and it influenced how she interacted with students and grappled with uncertainties. Ayaoba described this phenomenon during a lecture where Prof. Lemur got confused during a particular WC discussion:

“So, so the teacher always tells students to —to be comfortable with uncertainties and not always knowing the right answer right away. And that kind of played out in that particular lecture, because when the students were in the larger group discussion when they were contributing what they discussed in their smaller groups, I think it kind of confused what the teacher had in mind earlier. So she had to like take a step back to kind of parse through what the students were suggesting, because it made her uncertain about what she thought the right answer should be. So, I thought that was an interesting way to see—to see how she would expect the students to grapple with not knowing the right answer right away, because she kind of experienced that in real time right in front of everyone. […] My role [in the SG] is just to provide a space where those [first-draft] ideas can be can be shared. Yeah, and make sure everyone could voice their thoughts in the group and voice their confusions or uncertainties that they may have as well.”

In this quote, she describes Lemur’s practice as something the professor seemingly did intentionally. However, as we discussed in previous sections, Lemur was engaged in this modeling practice subconsciously and she herself did not recognize it until watching her own classroom video in interviews. Ayaoba’s deep understanding of and alignment with Lemur’s practice shaped her role understanding in “providing a space for first draft ideas to be shared” in the way Lemur had modeled. This mechanism of alignment was further evidenced during member checking, as Lemur saw Ayaoba’s activity system as more deeply aligned with her own than she had expected based on what she had communicated with the LAs. Lemur said that she often communicated things to the LAs in a practical way; however, she saw many of these practical motives become part of Ayaoba’s sense-making, and that Ayaoba’s sense-making motive matched Lemur’s motive and the collective object at the time. This was especially interesting to Lemur, because she had been unaware of this until our member checking almost two years after the data collection semester—Lemur described Ayaoba as a “reserved” LA, and so they often did not have informal conversations about their pedagogical intent. Lemur said that seeing this alignment, “for me, it was like, I’m so proud,” because she had specifically recruited Ayaoba to be an LA for the class.

Here, we provided evidence of both Cosog and Ayaoba’s learning in practice through how they internalized and made sense of the collective activity system and externalized it through their own unique moves and rules as an LA practicing in the neighboring and central activity. For Cosog, this manifested in how he resolved an explicit contradiction he experienced between his sense-making motive and the collective object of the neighboring activity to create a coherent practice for himself. This learning through contradiction resembles a classic activity theoretical expansive cycle. Whereas for Ayaoba, this learning came from deep synergy and coherence with the collective activity and how she extended and built upon it. We call this “consonant” learning and have not found prior literature precedent for it. We also demonstrated learning through contradiction in the section above with Shin’s division of labor that supported students to guide each other toward canonically correct ideas. Similarly, Capen underwent consonant learning leading to her outcome that was about progress in scientific practices. Each LA in each of our three cases had activity components that either disagreed with or went beyond what the professor had explicitly communicated (see Appendix for an example from each LA). For example, in Prof. Beaker’s class, LA Mango had a strong secondary motive to support students to interact with and help each other, both because it supported their conceptual understanding but also because it led to better morale and stress relief. Although Beaker did not emphasize student–student interaction in his meetings with LAs, he did hire Mango based on the interpersonal skills he had observed when Mango had been a student in his class—it was something Beaker valued, but did not coach his LAs on. Mango deeply internalized and externalized the importance of this, in part because of his own family experiences that valued collaboration—i.e., the activities he participates in beyond school.

What all LAs have in common is that their learning in practice reciprocally shaped and was shaped by the collective activity. In some cases, that was more explicit, for example, when Shin and Cosog created rules and role understandings that allowed them to reconcile the instructor’s explicit rules about LAs not guiding students with their own personal beliefs about learning. In other cases, it was more implicit, such when Capen, Ayaoba, and Mango placed special value on and personalized the collective object in ways that made sense to them and their own prior experience. Each contradiction or alignment came from how they experienced and made sense of the collective activity, and led to them creating unique components that transformed the activity system, which is a key definition for expansive learning. These findings demonstrate how the complex aspects of the system we explored before—the unique aspects of different LA-facilitated classrooms, the coherence of LAs’ practical and sense-making motives, and the coherence or contradiction between these motives and the collective objects—all influence LA learning in practice as something that is deeply contextualized and transformative.

Limitations

Our study has several limitations. Our analysis was based on 2 out of 3 of each participants’ interviews. It is possible that there were important aspects of participants’ practice that we missed by not analyzing the third interview; however, we found that differences between interviews tended to relate to the specifics of that day’s lecture materials rather than differences in their more general objects and rules. In addition, we did not look at change over time, and rather considered the LA as engaged in a single activity system over the course of the semester; understanding about development and learning came from the LAs’ self-report, rather than from a longitudinal analysis. We were also limited in our ability to identify some types of contradiction and consonance. One reason is a limitation of our data source: many of the instances of contradiction and consonance we identified in our analysis were not explicitly mentioned by participants themselves. Rather, they were primarily visible when comparing participants’ understandings of the activity systems with each other. A second reason is a limitation of our analysis. Unique components resulting from alignments were particularly difficult to identify, as it was not immediately clear if they came from the LA themselves, or if they came from a neighboring activity that we as researchers did not have access to, such as preparation meetings or pedagogy courses. We were also only able to share a small subset of interviews with instructor participants, whose insight was crucial for analyzing consonance, because they were able to report whether they had taught the LAs something or not. Thus, it is possible there are more instances of alignment in our dataset that we missed as outsiders to these activity systems.

Discussion

This paper uses cultural historical activity theory (CHAT) to conduct a close investigation of how different implementations of the LA model compare across contexts, and how these differences contribute to how and what LAs learn in their practice. This contributes to and bridges two broader bodies of literature focusing on differences in LA model implementation and LA learning and development.