Abstract

Background

Change strategies may leverage interpersonal relationships and conversations to spread teaching innovations among science faculty. Knowledge sharing refers to the process by which individuals transfer information and thereby spread innovative ideas within an organization. We use knowledge sharing as a lens for identifying factors that encourage productive teaching-related conversations between individuals, characterizing the context and content of these discussions, and understanding how peer interactions may shape instructional practices. In this study, we interview 19 science faculty using innovative teaching practices about the teaching-focused conversations they have with different discussion partners.

Results

This qualitative study describes characteristics of the relationship between discussion partners, what they discuss with respect to teaching, the amount of help-seeking that occurs, and the perceived impacts of these conversations on their teaching. We highlight the role of office location and course overlap in bringing faculty together and characterize the range of topics they discuss, such as course delivery and teaching strategies. We note the tendency of faculty to seek out partners with relevant expertise and describe how faculty perceive their discussion partners to influence their instructional practices and personal affect. Finally, we elaborate on how these themes vary depending on the relationship between discussion partners.

Conclusions

The knowledge sharing framework provides a useful lens for investigating how various factors affect faculty conversations around teaching. Building on this framework, our results lead us to propose two hypotheses for how to promote sharing teaching knowledge among faculty, thereby identifying productive directions for further systematic inquiry. In particular, we propose that productive teaching conversations might be cultivated by fostering collaborative teaching partnerships and developing departmental structures to facilitate sharing of teaching expertise. We further suggest that social network theories and other examinations of faculty behavior can be useful approaches for researching the mechanisms that drive teaching reform.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Evidence shows that learner-centered instructional strategies result in improved student learning outcomes (Daempfle, 2006; Freeman et al., 2014; Handelsman et al., 2004, 2007; Schroeder et al., 2007) yet, lecturing remains the predominant teaching mode in undergraduate science courses (Borrego et al., 2010; Durham et al., 2017; Henderson & Dancy, 2009Stains et al., 2018). There are a wide variety of barriers and drivers to instructional change, which include both contextual elements and personal factors (Andrews & Lemons, 2015; Austin, 2011; Brownell & Tanner, 2012; Gess-Newsome et al., 2003; Henderson & Dancy, 2007; Lund & Stains, 2015; Shadle et al., 2017). These barriers and drivers are contained within different levels of the academic system (e.g., individual, department, institution, discipline). Understanding the influence of each level on faculty members’ practices is critical to advancing instructional transformation (AACU, 2014; Austin, 2011; Elrod & Kezar, 2015). One of the levels recently targeted in the literature for its potential to promote and sustain instructional transformation is the academic department (AACU, 2014; Austin, 2011; Corbo et al., 2016; Musante, 2013; Reinholz & Apkarian, 2018; Reinholz et al., 2017; Shadle et al., 2017; Wieman, 2017; Wieman et al., 2010). The current approach is to enhance instructional change by developing a departmental culture that embraces and encourages evidence-based teaching practices (Quan et al., 2019; Reinholz et al., 2019a, 2019b). This culture-oriented approach is based on individuals’ behaviors and relationships between individuals.

Characterizing relationships between faculty within a department is important, since studies have hypothesized that faculty social interactions may directly influence change in higher education (Henderson et al., 2019; Kezar, 2014; Quardokus & Henderson, 2015). For example, Lane et al., (2019) surveyed faculty on their teaching-related social networks as well as their teaching practices and found evidence for conversations about teaching among departmental colleagues influencing (positively or negatively) a faculty member’s instructional practices. Another study by Andrews et al., (2016) identified characteristics of departmental colleagues that are more likely to promote instructional change among their discussion partners. In that study, the authors surveyed (N = 52) and interviewed (N = 34) faculty from across four life-sciences departments at a single institution regarding their interactions related to undergraduate teaching. Both qualitative and quantitative results suggested that discipline-based education research (DBER) faculty members, who were perceived by departmental colleagues as knowledgeable about teaching, were sought out by their colleagues for resources and information about teaching. The authors concluded that DBER faculty members promoted greater change in teaching than other faculty in the department.

These studies point to the important role that knowledgeable others potentially play in supporting instructional transformation within a department. Two recent studies have focused their attention on knowledgeable others to identify their sphere of influence. Both of these studies suggest that faculty who regularly use innovative teaching practices are more likely to talk to each other about teaching and less likely to discuss teaching with other faculty who do not report using innovative practices (Lane et al., 2020; McConnell et al., 2019). Taken together, these results imply that faculty with knowledge about innovative teaching likely play an important role in improving college teaching among their peers, but that the impact may not be as widespread across a department as it could be. To design change strategies that could amplify the influence of knowledgeable others within a department, we need to better understand the quantitative connections mapped through social network surveys by conducting in-depth investigation into the nature and substance of these relationships. The present study addresses this gap in the literature by richly describing the context, content, and perceived impact of discussions about teaching that occur between knowledgeable faculty members and their peers. The research questions associated with these goals are:

-

1.

What characterizes the relationship between knowledgeable STEM faculty members and their discussion partners?

-

2.

What types of knowledge are shared between faculty during teaching-related conversations?

-

3.

What are the perceived impacts of these teaching conversations on faculty, courses, and students?

In the discussion, we leverage these findings to hypothesize factors that may encourage the spread of teaching knowledge within science departments.

Framework for knowledge sharing

Knowledge sharing between individuals is known to impact both individual and organizational learning (Andrews & Delahaye, 2000; Hora & Hunter, 2014; Ipe, 2003; Nidumolu et al., 2001) and aid in dissemination of innovations within organizations (Armbrecht et al., 2001). The ideals of knowledge sharing focus on the fact that individuals hold important knowledge within an organization (Ipe, 2003). Ipe (2003) developed a framework rooted in an extensive literature review that encapsulates how knowledge is shared between individuals in an organization. While this particular framework by Ipe was originally developed in a business context, it has been previously applied to higher education (e.g., Al-Kurdi et al., 2018; Seonghee & Boryung, 2008). This is a productive framework for the present study, since it focuses on the exchange of knowledge between individuals (rather than between organizational units) and describes how different aspects of an organizational environment enable or limit knowledge sharing.

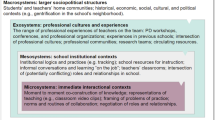

Ipe defines knowledge sharing as “the process by which knowledge held by an individual is converted into a form that can be understood, absorbed, and used by other individuals” (2003, pg. 341). The framework that emerged from the literature review focuses on four factors: opportunities to share, motivation to share, nature of the knowledge, and culture of the work environment. Each factor is important on its own, but all four factors are interconnected as Fig. 1 illustrates.

Knowledge sharing framework adapted from Ipe (2003). This framework focuses on how information is exchanged between individuals within an organization. The diagram shows how the various factors interact with each other to affect knowledge sharing

Opportunities to share knowledge can be formal (e.g., work teams, workshops, or technological systems explicitly designed to promote information dissemination) or informal (e.g., personal relationships or social networks). Research suggests that informal channels result in the largest amount of knowledge shared, since these formats enable development of trusted relationships among conversation partners. Many change strategies in higher education utilize dissemination of knowledge and other modes of discussion between faculty as an important element of that strategy (Henderson et al., 2011). Prior work often focuses on formal mechanisms, such as co-teaching, faculty learning communities, or workshops, but there is less discussion in the literature on creating informal or casual opportunities to share teaching knowledge (Cox, 2004; Henderson et al., 2011).

An individual’s motivation to share knowledge is impacted by internal motivators, such as the power attached to the knowledge and reciprocity in the sharing process. In certain environments, knowledge that confers power may be hoarded. For example, in a business setting, highly valuable knowledge may be hoarded when individuals perceive that holding the knowledge increases their status or reputation (Andrews & Delahaye, 2000). However, individuals are more likely to share their knowledge if they anticipate that their action of sharing will benefit them in some way.

Motivation to share can also be impacted by external factors. According to Ipe’s review, trust between individuals is one of the most critical factors with some studies demonstrating that without trust, formal knowledge-sharing processes are ineffective (Andrews & Delahaye, 2000). However, studies of knowledge sharing in higher education suggest that the role of trust in knowledge sharing may vary from one institutional or national context to the next. At a South Korean university, researchers analyzed 70 survey responses from faculty concerning factors promoting knowledge sharing (Seonghee & Boryung, 2008). Their results showed that faculty members’ perceptions of the importance of sharing teaching and research materials was the most influential factor for knowledge sharing among faculty, but trust was not a statistically significant factor. Another study at a Portuguese university found trust to strongly influence faculty members’ intention to share knowledge (Chedid et al., 2020). Yet another study applied game theory to examine knowledge sharing between faculty in Iran (Tabatabaei et al., 2019). Their results suggested that trust could lead to an increase of knowledge sharing, but only for faculty who were motivated to acquire more general knowledge and not for faculty who were motivated to improve their teaching performance (Tabatabaei et al., 2019). Finally, Roxå and Mårtensson (2009) conducted a study in Sweden in which they used surveys (N = 106) to study conversations that faculty had about teaching. Study participants spanning a variety of disciplines were either attendees at a national teaching and learning conference or part of a pedagogical course. Participants in this study relied on a small number of discussion partners whom they trusted and who were interested in discussing teaching. Similarly, our prior work has found that STEM faculty prefer sharing their knowledge about innovative teaching with colleagues who have similar teaching values (Lane et al., 2020).

Two other external factors can influence an individual’s motivation to share knowledge. The power dynamics between two individuals are key aspects of their relationship that influence knowledge sharing, and some studies have shown that individuals may be unwilling to share information that negatively reflects on them (Milliken et al., 2003). Another external factor impacting an individual’s motivation to share knowledge relates to the real and/or perceived rewards and penalties for sharing or withholding knowledge. With respect to the nature of the rewards necessary to promote knowledge sharing, Bartol and Srivastava (2002) propose that monetary rewards incentivize knowledge sharing through formal channels, while intrinsic and intangible rewards (e.g., being recognized by peers) incentivize informal knowledge sharing processes.

Finally, the nature of knowledge includes both the type and perceived value of the knowledge (Ipe, 2003). Few studies have explored the nature of knowledge that is shared between faculty with respect to teaching. Andrews et al., (2016), who explored STEM faculty members’ teaching conversations and the perceived impact of these conversations on their teaching, points to a variety of knowledge exchanged. Some of the resources that faculty in the study reported receiving as part of their interactions with colleagues were instructional materials and useful feedback. In addition to the type of knowledge being shared, the perceived value of knowledge also impacts individuals’ choices to share it with both organizations and individuals (Armbrecht et al., 2001). Whether increased value results in increased sharing can depend on many additional factors, including the culture of an organization, the competitiveness of an environment, and the sense of ownership over that knowledge (Ipe, 2003).

The three factors described above are all influenced by the culture of the work environment, which reflects the values, norms, and practices of the organization that can ultimately promote or inhibit knowledge sharing (De Long & Fahey, 2000; Ipe, 2003). Indeed,

“the culture of the organization dictates to a fairly large extent how and what knowledge is valued, what kinds of relationships and rewards it encourages in relation to knowledge sharing, and the formal and informal opportunities that individuals have to share knowledge.” (Ipe, 2003, p. 352–353).

Studies of knowledge sharing in higher education settings also indicate the importance of organizational and national culture in regard to knowledge sharing. A systematic review of the literature related to knowledge sharing in higher education conducted by Al-Kurdi et al., (2018) suggested that the impact of culture is complex and that institutional culture, national culture, and the local environment of the department or unit may all play a role in knowledge sharing (Al-Kurdi et al., 2018). Furthermore, local culture may alter which factors are most relevant for promoting knowledge sharing (Al-Kurdi et al., 2018; Ramayah et al., 2013).

In this study, we employ this framework for knowledge sharing within organizations to characterize the factors that lead to knowledge sharing (opportunities to share) and the type of information and resources shared (nature of knowledge), along with the perceived impacts of these teaching conversations among STEM faculty.

Methods

Context and participants

Faculty interviewees (n = 19) were recruited from three departments (biology, chemistry, geoscience) at three research universities. All three universities had instructional change initiatives on campus that were either complete or in progress at the time of the interviews. Interviewees were individuals that we identified as innovative instructors. For the purposes of this study, we defined innovative instructors as faculty who had participated in some part of the instructional change initiatives at their institution, such as workshops or long-term projects, and who were categorized as high users of evidence-based instructional practices (EBIPs) based on a set of survey questions (Additional file 1: Appendix A). We focused on these faculty assuming that they had knowledge about innovative teaching that would be beneficial to their peers.

Interviewees varied in the type of position they held, including tenure-line research faculty as well as faculty whose primary responsibilities were teaching. We emailed up to 10 faculty members from each department. Faculty were sent a reminder email 7–10 days after initial contact.

Data collection

Our interview protocol was rooted in principles from social network theory and consisted of two parts: (1) identification of each faculty’s teaching-related egocentric network and (2) characterization of the context, nature, and perceived impact of conversations with different types of conversation partners.

Part 1: development of egocentric networks around teaching

Social networks can help identify who talks to whom, which individuals may be influential to promote change based on their interpersonal connections, and if there are any personal characteristics that make conversation between people more likely (e.g., Henderson et al., 2019). In an academic context, a bounded social network may consist of all faculty within a department, where the department serves as the boundary of the network (Borgatti et al., 2009; Crossley et al., 2015; Van Waes et al., 2016). However, in this research, we were interested in identifying which colleagues the interviewees discussed teaching with and acquiring a rich description of those discussions. Personal networks (i.e., egocentric networks) can thus be used to elicit the interactions one person has with others without defining the boundaries of a larger social network (Van Waes et al., 2016).

We began each interview by asking the interviewee to name 3–5 people with whom they have discussed teaching in the previous year. Interviewees then arranged those individuals on a set of three concentric circles (arranged as a bullseye), placing the individuals whom the interviewee spoke with most nearer to the center and those whom they spoke to less further from the center. Interviewees were encouraged to define “most” using their own interpretation. When asked what metrics they used to arrange individuals, interviewees reported using frequency of conversations, quality of those conversations, and the overall amount of time spent talking about teaching. This concentric circle method is elaborated in Additional file 1: Appendix B and is similar to that described by Van Waes and Van de Bossche (2019).

Part 2: characterization of teaching conversations with different types of conversation partners

What an individual learns through a change effort may be related to the strength of their social relationships (Tenkasi & Chesmore, 2003). Tie strength can be described or measured in multiple ways, such as the number of contexts in which two people interact, the depth or length of their interactions, or the frequency at which they interact (Petróczi et al., 2007). It is important that departments contain both strong and weak ties, since they provide access to different types of knowledge (Haythornthwaite, 2002; Tenkasi & Chesmore, 2003). Strong ties support the exchange of knowledge that was originally acquired through personal experience (Hansen, 1999; Reagans & McEvily, 2003; Uzzi, 1997), whereas weak ties support the exchange of knowledge that is easily codified or written down, such as data in a spreadsheet (Hansen, 1999).

Because of the importance of tie strength when discussing knowledge sharing, we chose to capture conversations faculty had with colleagues with whom they had stronger ties (close discussion partners) and weaker ties (far discussion partners), which allowed us to capture a wide breadth of potential teaching conversations. We selected the first person placed in the innermost circle of their egocentric network (i.e., who the interviewee talked to about teaching most often) and the first person placed in the outermost circle (i.e., who the interviewee talked to least often about teaching) as the close and far discussion partners, respectively. In the rare instances when the interviewee did not utilize the outermost circle of the concentric circles, we randomly selected a far discussion partner from the middle circle. In addition, we avoided asking questions about the interviewee’s spouse (when known before the selection of close and far discussion partners) and did not ask questions about anyone on the research team. In cases where the discussion partner who would have been selected fell into one of these two categories, we selected the next logical discussion partner instead following the same procedure as described above. For each of the two discussion partners, we asked interviewees the same set of questions which aligned with our goals of characterizing the relationship between interviewees and their discussion partners, the types of knowledge shared between faculty during teaching-related conversations, and the perceived impacts of teaching conversations on faculty, courses, and students (Additional file 1: Appendix B).

Interviews ranged from approximately 30 min to 2 h. The complete interview protocol is shared in Additional file 1: Appendix B. Interviews were audio recorded and conducted either in person or by video conferencing. Audio recordings were transcribed using a computer automated transcription service, and AKL checked transcription of interviews as necessary by referring to the original audio recording.

Qualitative analysis

Four members of the team (coders: AKL, BAC, LBP, and MS) conducted qualitative analysis on the interview transcripts, which proceeded in four stages (summarized in Additional file 1: Fig. S1). The first stage was familiarizing ourselves with the data and deciding upon a coding approach. This stage included each coder reading three transcripts, one from each university, and discussing the content of the transcripts. Building on the knowledge sharing framework, we continued reading transcripts (for a total of nine read) and identified the following concepts relevant to our research questions: characteristics of the relationship, the topics discussed, and perceived impacts of the conversation on the interviewee and their course.

Second, the coders summarized the interview responses based on these major concepts. We chose to summarize the data to reduce it to a more manageable amount. During this stage, a pair of coders was responsible for summarizing in relation to each major concept. AKL was a member of every pair to increase consistency across summaries and have one coder deeply familiar with all the data. Summaries were done separately for the close and far discussion partner capturing all the contexts in which the interviewee and the discussion partner talked (e.g., casual conversations, committee meetings, working on a project together). Each coding pair took detailed notes throughout the summary writing process and came to consensus on the summaries, and AKL shared updates to all coders. Consensus summaries were stored in a spreadsheet organized by interviewee and major concept.

Third, the coders developed separate codebooks for each major concept and assigned codes to the summaries. One coder led the coding of each major concept and then paired with a second coder to review the list of codes and the assignment of codes to summaries. After review, the original coder and their partner discussed any issues, refined the codebooks, and came to a consensus on code application. Codebooks were emergent rather than prescribed and are included in Additional file 1: Appendix C. Finally, all coders reported out to each other about the codebooks. The coders discussed the codebooks to check for any biases and to see if there were common themes across codebooks. When there were similar codes used in different codebooks, the coders tried to align the language of the codes to reflect this similarity.

The fourth and final stage was sense making (Charmaz, 2006; Saldaña, 2016). In this final stage, all four coders worked together to review the coding of the major concepts for both the close and far discussion partners by iteratively reviewing notes, summaries, and code assignments. Coders looked for differences and similarities between all of the close and far discussion partners. Finally, coders compared the code books and themes that they identified to the knowledge sharing framework considering cases, where the themes aligned with the framework and noting times when the framework did not reflect the themes.

While coding, three of the four coders did not know the gender or racial/ethnic identities of the interviewees and the interviewer took care not to reveal these characteristics. Therefore, interviewees were assigned pseudonyms that were gender neutral and could represent a variety of races/ethnicities. Quotes were lightly edited for grammar and clarity, and ellipses represent statements that have been omitted. In addition, quotes that are shared in the results were selected by returning to the summaries to identify individuals whose experiences were represented by a particular theme, and then returning to those transcripts to identify quotes that exemplified those experiences.

Results

In this section, we report on the major emergent themes related to each of our research questions and how these themes differ among close and far discussion partners.

Characteristics of the relationships between knowledgeable STEM faculty members and their discussion partners

To explore the characteristics of these relationships between faculty and their teaching discussion partners, we asked questions about the frequency of their conversations, how they would characterize the conversations, and how they began talking to their discussion partners. The frequency with which interviewees talked to their close discussion partner ranged from daily to monthly and their far discussion partners ranged from weekly to once a semester (Fig. 2). The overlapping distribution of discussion frequencies between close and far partners reflects the idea that the interviewees might have different personal tendencies towards discussion frequency. Thus, the comparison of close versus far partners reflects a relative nearness to the interviewee, rather than any defined interaction frequency.

Characteristics mentioned by the interviewees when describing their relationships with their close and far conversation partners included their degree of course synchronization (e.g., co-teaching), office locations, newness to the university, and formal departmental or institutional roles. However, we observed differences between the relationships of close and far discussion partners (codebook located in Additional file 1: Table C1, associated quantitative results found in Additional file 1: Table D1).

First, a significant majority of the interviewees had close discussion partners who co-taught with them or had similar teaching assignments, such as teaching the same course or related courses. In these cases, it was common for interviewees to discuss collaborating with their close discussion partners on their teaching as they synchronized their responsibilities either across courses or within a course. One participant, Avery, described that their close discussion partner chose to align their course with Avery’s course,

“So we are free to teach what we like in those classes…But she chooses to match [her class to mine]. It’s just that [her class] doesn’t have a lab. So we teach very, very similarly and we talk a lot about where we’re up to. What are you teaching this week? Where are you up to? Oh, I’m on this assignment. Are you on that?”

By contrast, only about a third of the far discussion partners had some level of course synchronization, the majority of which consisted of teaching different but related courses (e.g., courses in a sequence).

Office proximity was another characteristic interviewees commonly used to describe their relationships with their discussion partners with approximately half of the interviewees mentioning location for the close or far discussion partners. However, while nine respondents said that their close discussion partners had nearby offices, office locations were varied for far discussion partners with three having nearby offices, two with offices that used to be close together, and four with offices in different locations.

Third, “being new to the university” was sometimes cited as a motivating factor in forming relationships between discussion partners. Just under half (N = 8) of the interviewees mentioned this when describing their relationship with their close partner. Either they started at the institution at the same time as their close partner or the two had a mentoring relationship (one was serving as the mentor to the newer one. In contrast, only four of the faculty mentioned this “being new to the university” factor when describing their relationship with their far discussion partner and all fell into the mentorship category.

Finally, interviewees described their relationship with their discussion partners as having some formal component such as being on a committee together or having a relationship based on either the interviewee or the discussion partner’s role in the department. Relationships based on one of the pair having a specific departmental role, such as department chair or undergraduate advisor, were more common between the interviewees and their far discussion partners; over half of interviewees reported having formal relationships with their far discussion partners compared to just over a third who described formal relationships with their close discussion partners. In some cases, the formal role could drive the topics of conversation. For example, Kai went to their far discussion partner to talk about teaching assignments and course goals, because he was Kai’s supervisor,

“He is my direct supervisor and so we talk about teaching in terms of both what am I going to teach [and] we talk about what are the goals for each of my classes and he gives me advice based on, ‘Oh, here’s some priorities for the department.”

Conversely, one interviewee mentioned providing information to a discussion partner who held a supervisory position. Angel self-described as having knowledge about teaching that was valued by their far discussion partner who was the current chair. Not only did Angel go to their far discussion partner for information, but Angel also felt it important to share their own knowledge with the current chair,

“I’ve been involved in some of these national conversations [about teaching] now for quite a while…and I end up bringing a lot of that information back to [the current chair], so he can figure out how to implement things and how things may need to move forward or change for things to improve.”

To provide additional context, we asked about how various discussions around teaching typically arose with each discussion partner. A large majority of interviewees described their teaching related conversations with their close partners as being impromptu or spontaneous and the same number described conversations with their far partners as impromptu (Fig. 3). In many cases, interviewees tied this occurrence to having nearby office locations, which they viewed as encouraging spontaneous conversations. For example, Quinn shared, “his office is right next to mine. So, we tend to stick our heads in and chat pretty regularly anyway.”

Nature of the conversations between faculty and their discussion partners. Bars represent the number of interview participants (n = 19) whose interactions with close (dark gray) and far (light gray) partners occurred predominantly in each different context. Discussion pairs could have more than one context

Types of knowledge shared between faculty during teaching-related conversations

Faculty exchanged both physical resources and materials as well as knowledge and ideas related to teaching. The elements shared and topics discussed could be organized into several broad categories: course delivery, teaching strategies, student-focused matters, degree of course synchronization, department-level matters, faculty improvement initiatives, and general teaching conversations. These large categories were further subdivided into more specific subcategories to fully capture the diversity of teaching topics discussed between faculty (codebook located in Additional file 1: Table C2, associated quantitative summaries found in Fig. 4 for overall categories and in Additional file 1: Table D2 for subcategories). Here, we will discuss a selection of the broader categories and associated subcategories. While interviewees discussed many topics with both close and far discussion partners, interviewees discussed a greater variety of topics with their close discussion partners. For example, Charlie listed a range of topics they discussed with their close discussion partner,

“Just approaches and strategies for [the discipline we teach]. We talk more generally about just what works, you know, flipped classrooms strategies or various of these active learning approaches. What’s effective and if it's worth doing new things. You know, why revamp something if the gains and learning are really minor or marginal general things like that. So, it’s pretty wide ranging.”

Types of knowledge shared between faculty during teaching-related conversations. Bars represent the number of interview participants (n = 19) whose interactions with close (dark gray) and far (light gray) partners included discussion and information sharing related to the given category. Discussion pairs could share more than one information type. Results broken down into additional subcategories are located in Additional file 1: Table D2

Course delivery, including structure of the course and course materials, was the most commonly discussed topic by interviewees with both their close and far discussion partners. The course structure included the learning management system, grading, scheduling, and classroom technology, while materials exchanged included information about the textbook, slides, assignments, or syllabi. Sometimes this exchange of materials could lead to future conversations, such as with Carter and their close discussion partner,

“I was in this position maybe a year before she came on board and, so, I have a little more experience or had a little more experience initially. And so. I gave her all my materials from this course and then together we recognized some deficiencies and we’ve been exploring ways of doing it better or different along the way.”

Many of the topics discussed were directly related to the characteristics of the relationship between the interviewee and their close discussion partner. For example, course synchronization was discussed between colleagues who shared the teaching responsibilities for a course or related courses. Jordan shared that they were working with their close discussion partner on restructuring a lab course,

“We’re in many ways revamping the lab section of this course. And so, we sort of are bouncing ideas off of each other [about] what’s the best approach for the labs to…get the students solving problems or what about their writing, trying to identify the things we want students to achieve in the course.”

Department-level matters was the one category more commonly discussed with far discussion partners than with close discussion partners. Over half of interviewees discussed departmental-level matters with their far discussion partners, while just over a third discussed these matters with their close discussion partners. Department-level matters included the subcategories of departmental affairs and faculty evaluation. The subcategory of departmental affairs included discussion about the departmental perspective on the curriculum or logistics, such as teaching assignments. For example, Jessie said,

“He’s part of the, um, university curriculum committee. So he has a lot of experience like reviewing new courses and kind of knowing what’s going on with general education at the university level. And so, a lot of my conversations with him are about, I’d say, curriculum design within the department.”

Conversations around faculty evaluations may have focused on the logistics of the evaluation or more generally how to identify good teaching.

In addition to talking about specific techniques or course materials, faculty also frequently engaged in general conversations or support related to teaching with their close discussion partners. Within these general teaching conversations, interviewees mentioned utilizing their colleague as a sounding board to “vent” their troubles related to teaching with about a third saying they vented with close discussion partners and only one participant saying the same of their far discussion partner. Reece described using their discussion partner as, “sort of like an outlet for venting, just kind of like things that didn’t go well or things that, you know, maybe where you feel like a bit of a failure.”

Help-seeking within teaching conversations

Interviewees were asked if they would go to their close or far discussion partners for help if an issue arose in the interviewee’s course, such as a problem with a teaching technique or with a student (Additional file 1: Fig. S2). Over half (N = 10) of the interviewees indicated that they would turn to their close discussion partner for help in any scenario, while few (N = 3) interviewees said the same of their far discussion partners. Alex said they would go to their close discussion partner, because they are willing to closely examine their teaching,

“I did and why? Because I have the most productive mutual relationship there because he is quite keen and insightful. Part of it is that we both are quite happy to self-eviscerate, like really self-examine what we’re doing [in the classroom] and think about its strengths and weaknesses.”

When interviewees described why they may not go to someone for advice, they included reasons, such as their discussion partner being inconveniently located or that they would go to someone else for advice before going to that discussion partner.

Interestingly, many interviewees said they would go to their close or far discussion partners for assistance only in scenarios, where they knew that discussion partner had relevant expertise or experience to share. For example, Sam described how they would go to their far discussion partner for advice on a teaching technique only if their far discussion partner had used the technique before,

“I think it depends on what I was doing. But I think if it was something like an active learning strategy that I had seen her use before in a workshop or something like that where I knew she had more experience than me with it, then I would probably ask her about it.”

Perceived impacts of teaching conversations on faculty, courses, and students

We also explored whether and how the interviewees perceived conversations with their discussion partners to have influenced their teaching practices (codebook located in Additional file 1: Table C3, associated quantitative results found in Fig. 5). Interviewees perceived greater impacts from the conversations they had with their close discussion partners, including changes to their course delivery, teaching strategies, and their affect, than with their far discussion partners. In fact, a majority of interviewees stated that conversations with their far discussion partners had no impact on how they teach.

Perceived impacts of teaching-related conversations. Bars represent the number of interview participants (n = 19) whose interactions with close (dark gray) and far (light gray) partners included discussion and information sharing related to the given category. Discussion pairs could share more than one impact type

Several interviewees described how conversations with both their close and far discussion partners impacted how they delivered their courses, such as by affecting course materials, policies, or feedback. For example, Kai stated,

“Yeah, I think drawing things out, that’s probably the biggest thing I got from him and probably just, honestly, figuring out how to manage course resources effectively for students, which sounds silly, but like figuring out how do you best post things for students.”

However, few interviewees specifically stated that their conversations about teaching resulted in a change in their teaching strategies or activities used in their classes, such as Avery who shared, “I think that what she gives me is the inquiry-based activities. Kind of like a mini activity that you can do in 10 min in a lecture.” Only four interviewees said their conversations with close discussion partners resulted in this kind of change and only one said so of conversations with their far discussion partner.

One commonly reported impact was not about action, but rather how the instructors felt about themselves and their teaching, which we labeled “instructor affect.” These impacts on instructor affect could include inspiration or a change in perspective, and multiple interviewees said that their discussion partners provided “validation.” Quinn talked about the importance of the validation their discussion partner gave them,

“This may sound strange, but a sense of validation because the fact that he is finding this innovation that I’m using is good because using this tool in my class is something of an innovation in the field. And so, it gives me some sense that there is utility beyond just my own course in what I'm doing, and that validation keeps me motivated to keep working at it.”

These impacts on instructor affect were more common as a result of conversations with a close discussion partner (N = 14) than their far discussion partner (N = 6).

One perceived impact category was directly related to students. These student-focused impacts included managing students, inclusive practices, and student engagement. One interviewee, Kym, said that their discussion partner helped them become more inclusive in the classroom,

“I think that I have become, I hope I have become a more inclusive teacher… I think she’s made me aware of things that I was not aware of before that I've since worked on. And so, I think I probably foster more community in my classes than I did before I knew her.”

This category was reported at similar frequencies by interviewees for both their close and far discussion partners. Notably, no one explicitly discussed the impacts conversations had on student learning.

Discussion

How can we facilitate productive teaching relationships and increase knowledge sharing?

The modified knowledge sharing framework used in this study (Ipe, 2003) provides a lens through which to understand how different factors affect the frequency, depth, and perceived impact of teaching-related knowledge sharing that occurs within an academic department. Within this framework, productive knowledge sharing depends on the (1) opportunities and (2) motivations faculty have to share as well as the (3) type and perceived value of teaching related information. These factors are influenced by the (4) broader culture that exists in a department around teaching and social interactions. While peer interactions have been cited as important factors influencing instructional practices (Andrews et al., 2016; Lane et al., 2019, 2020; McConnell et al., 2019), our study sought to understand what brings faculty together (opportunities to share), what they discuss (nature of knowledge), and how their conversations might impact their courses. Since we previously reported on motivation to share knowledge within the population participating in this study (Lane et al., 2020), we did not explore this aspect of the framework here. By characterizing the conversations faculty have with close and far discussion partners, we sought to capture the complex interactions that influence knowledge sharing as well as identify potential ways that departments can cultivate social interactions that support the implementation of learner centered practices.

Our data indicate that close discussion partners had greater perceived impacts on their peers’ teaching. There were organizational structures that helped promote these close relationships by providing more frequent opportunities to share. Teaching courses with some relation (e.g., co-teaching or coordinated teaching) and having offices close to each other were cited as offering ample opportunity for conversations to occur. The interviewed faculty received validation from their close discussion partners, which encouraged the faculty to continue using learner-centered practices or try new instructional practices in their courses. Finally, when interviewees did seek out help, they were more likely to go to their close discussion partners for assistance, although sometimes interviewees would only seek out their close discussion partners for help with specific issues.

As described, far discussion partners had less reported impact on interviewees, which may be due to several factors. The most obvious factor limiting the impact of far discussion partners is that teaching conversations between them and interviewees were less frequent thereby providing fewer opportunities to share. Moreover, interviewees often interacted with their far discussion partners in a formal context, such as being on committees together or during required meetings to check in with departmental leadership. During these interactions, the nature of knowledge discussed varied and tended to focus slightly more on departmental topics, such as student course evaluations, among other topics. In the future, these formal structures in departments could be leveraged to influence departmental culture in a manner that promotes further knowledge sharing. In addition, interviewees were less likely to go to their far discussion partners when they had a teaching-related problem even though they may have discussed evaluations that should aim to be diagnostic of teaching. Overall, the dearth of perceived impacts of conversations with far discussion partners on interviewees’ teaching suggests that departmental structures and cultures could evolve to enable committee work and other formal interactions to translate directly into changes that support transformative teaching practices. For example, annual review meetings could include conversations about peer review of teaching, student evaluations, or other collected metrics. These conversations could carve out time to reflect on this information and brainstorm practical and specific course improvements.

Our data also revealed similarities in the types of information shared with close and far partners. Faculty met with close and far partners under similar circumstances including both impromptu and arranged meetings and workshops, though the frequency of meetings differed between close and far partners. Conversations around teaching frequently focused on course delivery, where faculty focused on the structure and logistics of courses, or department-level matters, all of which have sufficient commonalities to be relatable between faculty who teach similar or different courses. However, there are some types of teaching related knowledge that were notably absent from interviewees’ descriptions despite being relevant for teaching improvement, such as sharing education research publications and data on student learning. The knowledge sharing framework suggests that different types of knowledge may be shared through different practices or methods (Ipe, 2003). It is possible that research publications and student data are either not shared among faculty at a noticeable frequency or, when they are shared, the process occurs outside of teaching-related conversations possibly through communications from campus units or in conversations about research rather than teaching. Another contributing factor might be that faculty place greater value on their personal teaching experiences than on student data and education research (Andrews & Lemons, 2015; Hora et al., 2014). Additional investigation is needed to describe how student data and education research knowledge is shared among faculty and throughout an institution and why that may not occur regularly during teaching-related conversations between immediate colleagues.

Ultimately, the goal of spreading teaching knowledge is to improve faculty practices and impact student learning and experiences. Student-focused impacts that interviewees mentioned included student engagement, expectations, or management rather than learning outcomes (Fig. 5). This lack of described impact on student learning outcomes may be because faculty think of classroom improvements as having a downstream impact on improving learning outcomes and, as such, describing learning outcomes was not salient to the interviewees. No matter the reason, faculty did not seem to directly discuss how teaching conversations impacted student learning (Fig. 5). As a result, more work needs to be done to investigate how these conversations about teaching relate to student learning.

The lack of focus on student learning in teaching-related conversations limits the broader impact of these conversations. Departments and faculty need to focus on obtaining and reflecting on student learning data/evidence as a primary objective. Existing structures, such as student course evaluations and annual review meetings, offer opportunities to share but the focus is on a type of knowledge that does not directly address student learning. Indeed, student evaluations provide insight about students’ satisfaction with their course and instructor rather than the learning they experienced. Adding evidence of learning to promotion and tenure documents as well as annual peer reviews and faculty meeting agendas would enable faculty to reflect on and more readily share practices that support student learning. One critical consideration is who will lead these changes in departments and ultimately serve as change agents. Some scholars have suggested that department chairs and deans are uniquely positioned to serve as change agents, meaning that institutions need to hire, promote, and train department chairs and deans to engage in this kind of work (Dennin et al., 2017).

Hypotheses to promote knowledge sharing

Based on findings from our faculty interviews, we describe two hypotheses rooted in Ipe’s knowledge sharing framework and social network theory. Each hypothesis proposes how science departments could increase knowledge sharing about teaching through facilitating formal and informal conversations between faculty about teaching and establishing new departmental norms and culture.

Hypothesis 1: Nurturing new teaching relationships promotes knowledge sharing by providing opportunities and motivation to share.

Our results show that close teaching relationships often stem from teaching the same course or having some type of formalized relationship, and it is these close teaching relationships, where teaching knowledge is most likely to be shared. Increasing the number of close teaching relationships through formal organizational structures, such as co-teaching, teaching teams, faculty learning communities, or assigning teaching mentors to new faculty, could increase the number of close relationships in the department (faculty learning communities: Cox, 2004). Through these relationships, faculty may not only build trust, which can increase motivation to share, but also provide ample opportunities to share knowledge. Previous work hypothesizes that co-teaching could be an effective faculty development method to promote use of teaching innovations (Cordie et al., 2020; Henderson & Dancy, 2009; Lane et al., 2020). Co-teaching takes many forms and more research is needed to determine which co-teaching models build closer relationships. We recognize that co-teaching can be a resource-intensive endeavor and expand upon this prior work by suggesting that other forms of teaching relationships can potentially be utilized to have the same effect, such as teaching as a team across sections or other models of peer teaching mentorship. Any formal methods that provide dedicated space and incentive to discuss teaching could have a positive impact.

However, our data suggests that structured relationships can, but do not always, result in building close relationships around teaching. Therefore, intentional training on creating opportunities to share teaching experience and student outcomes is needed to cultivate discussions that generate impacts through close teaching relationships. Faculty Learning Communities that bring together new faculty or focus on similar or shared courses (e.g., a lab course) could generate conversations that lead to sharing of resources and ideas and create an environment in which faculty receive validation around teaching. Research is needed to examine what formal systems can best provide these opportunities and build close relationships in different departmental contexts. It is possible that not all formal co-teaching or mentoring assignments result in close relationships, but research may conclude that formalizing these relationships at least increases the odds of a close relationship forming.

Hypothesis 2: Departments that are successful in advancing instruction have structures that enable sharing of teaching expertise.

Prior work suggests that university teaching is often treated as a solitary endeavor (e.g., Gizir & Simsek, 2005; Handal, 1999; Roxå & Mårtensson, 2009). We found that while many interviewees reported that they would seek help from discussion partners about teaching, the majority qualified these responses by saying they would seek help only if they knew that a peer had relevant knowledge. This qualification limits the amount of help-seeking that faculty can engage in, because it requires faculty to know about each other’s teaching before seeking each other out for assistance. If faculty only seek assistance when they know a peer has knowledge to share, then the benefits of brainstorming and exchanging ideas casually may be devalued. Faculty may feel vulnerable sharing their struggles due to the constant state of evaluation that is often part of the departmental and institutional culture. Departments should seek to foster environments and cultures, where improving student learning is a primary desired outcome and where faculty work together to achieve this outcome. An intermediate step that departments could take is to hold meetings, where faculty are encouraged to share what teaching approaches they are using or observe each other’s classes so that they are more aware of each other’s experiences and expertise thereby reducing a barrier for help-seeking by making peers more aware of each other’s skill sets.

Other considerations and future directions

In addition to the research needed to confirm or refute the aforementioned hypotheses, questions remain about how research on knowledge sharing in organizations may or may not apply to higher education, to science departments, and to knowledge specifically about teaching. Our investigation focused on experiences and knowledge sharing between faculty who regularly use EBIPs and their discussion partners. Future work could include a wider range of faculty to examine their role in knowledge sharing and potentially identify barriers to knowledge sharing. Moreover, our study did not probe directly the role of departmental culture and the different drivers of motivation to share knowledge that could be influential, such as the role of trust, power, reciprocity, and rewards (Ipe, 2003). These aspects of the framework should be explored further.

Furthermore, future work should be done to investigate knowledge sharing in other higher education science departments as there may be nuances or factors that we did not uncover that depend on local culture and structures related to sharing teaching knowledge. For example, researchers may want to interview department leadership and other faculty about the role that leadership has in motivating sharing, specifically how the actions of leadership contribute to trust and rewards within the department. In general, this knowledge sharing framework may manifest differently depending on the departmental culture and the university type and further work is needed to refine the framework for a higher education setting. Finally, studies examining departmental social networks and their impact on EBIP use and practice could consider combining social network data with in-depth interviews to gain a more complete picture of the department.

Conclusions

We have used a knowledge sharing framework to investigate the extent to which social interactions result in the dissemination of teaching and EBIP knowledge in science departments. Our research examined one aspect of social networks, ego or personal networks, and revealed that, when compared to far discussion partners, close discussion partners have a greater perceived impact on faculty through conversations on practical aspects of teaching as well as by providing validation of teaching approaches or struggles. By characterizing these social interactions, we were able to better understand the opportunities to share and the nature of knowledge shared between discussion partners, thereby providing detail and nuance to how interpersonal relationships enable teaching related information to flow through a department. We hypothesized mechanisms based on the framework that may contribute to more regular knowledge sharing within departments. Specifically, we hypothesize that (1) nurturing new teaching relationships promotes knowledge sharing by providing opportunities and motivation to share and (2) departments that are successful in advancing instruction have structures that enable sharing of teaching expertise. We further propose that social network theories and other examinations of faculty behavior can be useful approaches for future research into understanding the mechanisms that facilitate teaching reform.

Availability of data and materials

The data sets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available to protect the identities of participants but some de-identified data may be available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- DBER:

-

Discipline-based education research

- EBIP:

-

Evidence-based instructional practice

References

AACU. (2014). Achieving systemic change: A sourcebook for advancing and funding undergraduate STEM education.

Al-Kurdi, O., El-Haddadeh, R., & Eldabi, T. (2018). Knowledge sharing in higher education institutions: A systematic review. Journal of Enterprise Information Management, 31(2), 226–246. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEIM-09-2017-0129

Andrews, K. M., & Delahaye, B. L. (2000). Influences on knowledge processes in organizational learning: The psychosocial filter. Journal of Management Studies, 37(6), 797–810. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6486.00204

Andrews, T. C., Conaway, E. P., Zhao, J., & Dolan, E. L. (2016). Colleagues as change agents: How department networks and opinion leaders influence teaching at a single research university. CBE-Life Sciences Education, 15(2), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.15-08-0170

Andrews, T. C., & Lemons, P. P. (2015). It’s personal: Biology instructors prioritize personal evidence over empirical evidence in teaching decisions. CBE-Life Sciences Education, 14(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.14-05-0084

Armbrecht, J., Chapas, R. B., Chappelow, C. C., Farris, G. F., Friga, P. N., Hartz, C. A., McIlvaine, M. E., Postle, S. R., & Whitwell, G. E. (2001). Knowledge management in research and development. Research Technology Management, 44(4), 28–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/08956308.2001.11671438

Austin, A. E. (2011). Promoting evidence-based change in undergraduate science education. Fourth Committee Meeting on Status, Contributions, and Future Directions of Discipline-Based Education Research, 1–25.

Bartol, K. M., & Srivastava, A. (2002). Encouraging knowledge sharing: The role of organizational reward systems. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 9(1), 64–76. https://doi.org/10.1177/107179190200900105

Borgatti, S. P., Mehra, A., Brass, D. J., & Labianca, G. (2009). Network analysis in the social sciences. Science, 323(5916), 892–895. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1165821

Borrego, M., Froyd, J. E., & Hall, T. S. (2010). Diffusion of engineering education innovations: A survey of awareness and adoption rates in U.S. engineering departments. Journal of Engineering Education, 99(3), 185–207. https://doi.org/10.1002/J.2168-9830.2010.TB01056.X

Brownell, S. E., & Tanner, K. D. (2012). Barriers to faculty pedagogical change: Lack of training, time, incentives, and tensions with professional identity? CBE Life Sciences Education, 11(4), 339–346. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.12-09-0163

Charmaz, K. (2006). Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis. Sage.

Chedid, M., Caldeira, A., Alvelos, H., & Teixeira, L. (2020). Knowledge-sharing and collaborative behaviour: An empirical study on a Portuguese higher education institution. Journal of Information Science, 46(5), 630–647. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165551519860464

Corbo, J. C., Reinholz, D. L., Dancy, M. H., Deetz, S., & Finkelstein, N. (2016). Framework for transforming departmental culture to support educational innovation. Physical Review Physics Education Research, 12(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevPhysEducRes.12.010113

Cordie, L. A., Lin, X., Brecke, T., & Wooten, M. C. (2020). Co-teaching in higher education: Mentoring as faculty development. International Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education, 32(1), 149–158.

Crossley, N., Bellotti, E., Edwards, G., Everett, M. G., Koskinen, J., & Tranmer, M. (2015). Social network analysis for ego-nets: Social network analysis for actor-centered networks. Sage.

Daempfle, P. A. (2006). The effects of instructional approaches on the improvement of reasoning in introductory college biology: A quantitative review of research. Bioscene Journal of College Biology Teaching, 32(4), 22–31.

De Long, D. W., & Fahey, L. (2000). Diagnosing cultural barriers to knowledge management. Academy of Management Executive, 14(4), 113–127. https://doi.org/10.5465/ame.2000.3979820

Dennin, M., Schultz, Z. D., Feig, A., Finkelstein, N., Greenhoot, A. F., Hildreth, M., Leibovich, A. K., Martin, J. D., Moldwin, M. B., O’Dowd, D. K., Posey, L. A., Smith, T. L., & Miller, E. R. (2017). Aligning practice to policies: Changing the culture to recognize and reward teaching at research universities. CBE-Life Sciences Education, 16(4), es5.

Durham, M. F., Knight, J. K., & Couch, B. A. (2017). Measurement instrument for scientific teaching (Mist): A tool to measure the frequencies of research-based teaching practices in undergraduate science courses. CBE-Life Sciences Education, 16(4), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.17-02-0033

Elrod, S., & Kezar, A. (2015). Increasing student success in STEM: a guide to systemic institutional change. A Keck/PKAL Project at the Association of American Colleges & Universities.

Freeman, S., Eddy, S. L., McDonough, M., Smith, M. K., Okoroafor, N., Jordt, H., & Wenderoth, M. P. (2014). Active learning increases student performance in science, engineering, and mathematics. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111(23), 8410–8415. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1319030111

Gess-Newsome, J., Southerland, S. A., Johnston, A., & Woodbury, S. (2003). Educational reform, personal practical theories, and dissatisfaction: The anatomy of change in college science teaching. American Educational Research Journal, 40(3), 731–767. https://doi.org/10.3102/00028312040003731

Gizir, S., & Simsek, H. (2005). Communication in an academic context. Higher Education, 50(2), 197–221. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-004-6349-x

Handal, G. (1999). Consultation using critical friends. New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 79, 59–70.

Handelsman, J., Ebert-May, D., Beichner, R., Bruns, P., Chang, A., DeHaan, R., Gentile, J., Lauffer, S., Stewart, J., & Tilghman, S. M. (2004). Scientific teaching. Science, 304(5670), 521–522.

Handelsman, J., Miller, S., & Pfund, C. (2007). Scientific Teaching. MacMillan.

Hansen, M. T. (1999). The search-transfer problem: The role of weak ties in sharing knowledge across organization subunits. Administrative Science Quarterly, 44(1), 82–111. https://doi.org/10.2307/2667032

Haythornthwaite, C. (2002). Strong, weak, and latent ties and the impact of new media. Information Society, 18(5), 385–401. https://doi.org/10.1080/01972240290108195

Henderson, C., Beach, A., & Finkelstein, N. (2011). Facilitating change in undergraduate STEM instructional practices: An analytic review of the literature. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 48(8), 952–984. https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.20439

Henderson, C., & Dancy, M. H. (2007). Barriers to the use of research-based instructional strategies: The influence of both individual and situational characteristics. Physical Review Special Topics Physics Education Research, 3(2), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevSTPER.3.020102

Henderson, C., & Dancy, M. H. (2009). Impact of physics education research on the teaching of introductory quantitative physics in the United States. Physical Review Special Topics Physics Education Research, 5(2), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevstper.5.020107

Henderson, C., Rasmussen, C., Knaub, A., Apkarian, N., Daly, A. J., & Fisher, K. Q. (Eds.). (2019). Researching and enacting change in postsecondary education: Leveraging instructors’ social networks. Routledge.

Hora, M. T., Bouwma-Gearhart, J., & Park, H. J. (2014). Exploring data-driven decision-making in the field: How faculty use data and other forms of information to guide instructional decision-making. WCER Working Paper No. 2014-3. Wisconsin Center for Education Research.

Hora, M. T., & Hunter, A. B. (2014). Exploring the dynamics of organizational learning: Identifying the decision chains science and math faculty use to plan and teach undergraduate courses. International Journal of STEM Education, 1(1), 1–21.

Ipe, M. (2003). Knowledge sharing in organizations: A conceptual framework. Human Resource Development Review, 2(4), 337–359. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534484303257985

Kezar, A. (2014). Higher education change and social networks: A review of research. Journal of Higher Education, 85(1), 91–125. https://doi.org/10.1353/jhe.2014.0003

Lane, A. K., McAlpin, J. D., Earl, B., Feola, S., Lewis, J. E., Mertens, K., Shadle, S. E., Skvoretz, J., Ziker, J. P., Couch, B. A., Prevost, L. B., & Stains, M. (2020). Innovative teaching knowledge stays with users. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 117(37), 22665–22667. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2012372117

Lane, A. K., Skvoretz, J., Ziker, J. P., Couch, B. A., Earl, B., Lewis, J. E., McAlpin, J. D., Prevost, L. B., Shadle, S. E., & Stains, M. (2019). Investigating how faculty social networks and peer influence relate to knowledge and use of evidence-based teaching practices. International Journal of STEM Education, 6(1), 28. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40594-019-0182-3

Lund, T. J., & Stains, M. (2015). The importance of context: An exploration of factors influencing the adoption of student-centered teaching among chemistry, biology, and physics faculty. International Journal of STEM Education. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40594-015-0026-8

McConnell, M., Montplaisir, L., & Offerdahl, E. (2019). Meeting the conditions for diffusion of teaching innovations in a university STEM department. Journal for STEM Education Research. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41979-019-00023-w

Milliken, F. J., Morrison, E. W., & Hewlin, P. F. (2003). An exploratory study of employee silence: Issues that employees don’t communicate upward and why. Journal of Management Studies, 40(6), 1453.

Milton, D. C. (2004). Introduction to faculty learning communities. New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 97, 5–23. https://doi.org/10.1002/tl.129/abstract

Musante, S. (2013). PULSE: Implementing change within and among life science departments. BioScience, 63(4), 254. https://doi.org/10.1525/bio.2013.63.4.4

Nidumolu, S. R., Subramani, M., & Aldrich, A. (2001). Situated learning and the situated knowledge web: Exploring the ground beneath knowledge management. Journal of Management Information Systems, 18(1), 115–150. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421222.2001.11045675

Petróczi, A., Nepusz, T., & Bazsó, F. (2007). Measuring tie-strength in virtual social networks. Connections, 27(2), 39–52.

Quan, G. M., Corbo, J. C., Finkelstein, N. D., Pawlak, A., Falkenberg, K., Geanious, C., Ngai, C., Smith, C., Wise, S., Pilgrim, M. E., & Reinholz, D. L. (2019). Designing for institutional transformation: Six principles for department-level interventions. Physical Review Physics Education Research, 15(1), 10141. https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevphyseducres.15.010141

Quardokus, K., & Henderson, C. (2015). Promoting instructional change: Using social network analysis to understand the informal structure of academic departments. Higher Education, 70(3), 315–335. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-014-9831-0

Ramayah, T., Yeap, J. A. L., & Ignatius, J. (2013). An empirical inquiry on knowledge sharing among academicians in higher learning institutions. Minerva, 51(2), 131–154. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11024-013-9229-7

Reagans, R., & McEvily, B. (2003). Network structure and knowledge transfer: The effects of cohesion and range. Administrative Science Quarterly, 48, 240–267.

Reinholz, D. L., & Apkarian, N. (2018). Four frames for systemic change in STEM departments. International Journal of STEM Education. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40594-018-0103-x

Reinholz, D. L., Corbo, J. C., Dancy, M., & Finkelstein, N. (2017). Departmental action teams: Supporting faculty learning through departmental change. Learning Communi-Ties Journal, 9, 5–32.

Reinholz, D. L., Matz, R. L., Cole, R., & Apkarian, N. (2019a). STEM is not a monolith: A preliminary analysis of variations in STEM disciplinary cultures and implications for change. CBE-Life Sciences Education, 18(4), mr4. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.19-02-0038

Reinholz, D. L., Pilgrim, M. E., Corbo, J. C., & Finkelstein, N. (2019b). Transforming undergraduate education from the middle out with departmental action teams. Change the Magazine of Higher Learning, 51(5), 64–70. https://doi.org/10.1080/00091383.2019.1652078

Roxå, T., & Mårtensson, K. (2009). Significant conversations and significant networks-exploring the backstage of the teaching arena. Studies in Higher Education, 34(5), 547–559. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070802597200

Saldaña, J. (2016). The coding manual for qualitative researchers (3rd ed.). SAGE Publications.

Schroeder, C. M., Scott, T. P., Toison, H., Huang, T. Y., & Lee, Y. H. (2007). A meta-analysis of national research: Effects of teaching strategies on student achievement in science in the United States. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 44(10), 1436–1460. https://doi.org/10.1002/TEA.20212

Seonghee, K., & Boryung, J. (2008). An analysis of faculty perceptions: Attitudes toward knowledge sharing and collaboration in an academic institution. Library and Information Science Research, 30(4), 282–290. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lisr.2008.04.003

Shadle, S. E., Marker, A., & Earl, B. (2017). Faculty drivers and barriers: Laying the groundwork for undergraduate STEM education reform in academic departments. International Journal of STEM Education. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40594-017-0062-7

Tabatabaei, M., Afrazeh, A., & Seifi, A. (2019). A game theoretic analysis of knowledge sharing behavior of academics: Bi-level programming application. Computers & Industrial Engineering, 131, 13–27.

Tenkasi, R. V., & Chesmore, M. C. (2003). Social networks and planned organizational change: The impact of strong network ties on effective change implementation and use. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 39(3), 281–300. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021886303258338

Uzzi, B. (1997). Social structure and competition in interfirm networks: The paradox of embeddedness. Administrative Science Quarterly. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429494338

Van Waes, S., Moolenaar, N. M., Daly, A. J., Heldens, H. H. P. F., Donche, V., Van Petegem, P., & Van den Bossche, P. (2016). The networked instructor: The quality of networks in different stages of professional development. Teaching and Teacher Education, 59, 295–308. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2016.05.022

Van Waes, S., & Van den Bossche, P. (2019). Around and around: The concentric circles method as a powerful tool to collect mixed method network data. In D. E. Froehlich, M. Rehm, & B. C. Rienties (Eds.), Mixed Methods Social Network Analysis (pp. 159–174). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429056826-15

Wieman, C. (2017). Improving how universities teach science. Harvard University Press.

Wieman, C., Perkins, K., & Gilbert, S. (2010). Transforming science education at large research universities: A case study in progress. Change the Magazine of Higher Learning, 42(2), 6–14.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was funded by the National Science Foundation (NSF) Division of Undergraduate Education (DUE) Grants to Boise State University (1726503), University of Nebraska-Lincoln (1726409), and University of South Florida (1726330). This material is based upon work supported by the NSF Graduate Research Fellowship Program under Grant 1746051. This material is based upon work supported by the NSF under Grant 1849473. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the NSF.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AKL, BAC, LBP, and MS were major contributors in writing and editing the manuscript, performing analysis, and working on experimental design. All other authors contributed to designing the study and editing the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

Guttman scale survey question, interview questions and directions, codebooks, and supplemental tables and figures.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lane, A.K., Earl, B., Feola, S. et al. Context and content of teaching conversations: exploring how to promote sharing of innovative teaching knowledge between science faculty. IJ STEM Ed 9, 53 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40594-022-00369-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40594-022-00369-5