Abstract

Background

Tigecycline has in vitro bacteriostatic activity against a broad spectrum of bacteria, including carbapenem-resistant Gram-negative bacteria (CR-GNB). However, the role of tigecycline in treatment of nosocomial pneumonia caused by CR-GNB remains controversial and clinical evidences are limited. We aimed to investigate the clinical benefits of tigecycline as part of the combination treatment of nosocomial CR-GNB pneumonia in intensive care unit (ICU).

Methods

This multi-centre cohort study retrospectively enrolled ICU-admitted patients with nosocomial pneumonia caused by CR-GNB. Patients were categorized based on whether add-on tigecycline was used in combination with at least one anti-CR-GNB antibiotic. Clinical outcomes and all-cause mortality between patients with and without tigecycline were compared in the original and propensity score (PS)-matched cohorts. A subgroup analysis was also performed to explore the differences of clinical efficacies of add-on tigecycline treatment when combined with various anti-CR-GNB agents.

Results

We analysed 395 patients with CR-GNB nosocomial pneumonia, of whom 148 received tigecycline and 247 did not. More than 80% of the enrolled patients were infected by CR-Acinetobacter baumannii (CRAB). A trend of lower all-cause mortality on day 28 was noted in tigecycline group in the original cohort (27.7% vs. 36.0%, p = 0.088). In PS-matched cohort (102 patient pairs), patients with tigecycline had significantly lower clinical failure (46.1% vs. 62.7%, p = 0.017) and mortality rates (28.4% vs. 52.9%, p < 0.001) on day 28. In multivariate analysis, tigecycline treatment was a protective factor against clinical failure (PS-matched cohort: aOR 0.52, 95% CI 0.28–0.95) and all-cause mortality (original cohort: aHR 0.69, 95% CI 0.47–0.99; PS-matched cohort: aHR 0.47, 95% CI 0.30–0.74) at 28 days. Kaplan–Meier survival analysis in subgroups of patients suggested significant clinical benefits of tigecycline when added to a colistin-included (log rank p value 0.005) and carbapenem-included (log rank p value 0.007) combination regimen.

Conclusions

In this retrospective observational study that included ICU-admitted patients with nosocomial pneumonia caused by tigecycline-susceptible CR-GNB, mostly CRAB, tigecycline as part of a combination treatment regimen was associated with lower clinical failure and all-cause mortality rates.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Nosocomial pneumonia, including hospital-acquired pneumonia (HAP) and ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP), are the leading cause of morbidity and mortality in the intensive care unit (ICU) [1, 2]. Among the various pathogens that cause nosocomial pneumonia, a focus on carbapenem-resistant Gram-negative bacteria (CR-GNB), especially CR-Acinetobacter baumannii complex (CRAB), CR-Enterobacteriaceae (CRE), and CR-Pseudomonas aeruginosa (CRPA), is motivated by the limited number of treatment choices available and poor treatment outcomes [3, 4]. According to the latest guidelines regarding multidrug-resistant organisms (MDRO), novel β-lactam/β-lactamase inhibitors, especially ceftazidime–avibactam, are currently the treatment of choices for CRE and CRPA [5,6,7]. However, clinical isolates with resistance to novel β-lactam/β-lactamase inhibitors are emerging [8]. For CRE with resistance to novel agents and for CRAB, combination therapy of old drugs, including polymyxin, tigecycline, minocycline, and aminoglycoside, should be considered, especially in those with moderate-to-high disease severity [5,6,7]. However, the optimal combination regimen of antibiotics remains uncertain.

Tigecycline has in vitro bacteriostatic activity against a broad spectrum of drug-resistant bacteria [9, 10]. However, tigecycline has a sub-optimal concentration in epithelial lining fluid, blood, and urine [11]. Previous randomized controlled trials failed to prove the efficacy of tigecycline in the treatment of nosocomial pneumonia [12]. Although recent HAP/VAP guidelines recommended against the use of tigecycline in nosocomial caused by CR-GNB [4], tigecycline is frequently used off-label due to the limited antibiotic choices for nosocomial pneumonia caused by CR-GNB. The latest MDRO guidelines recommended including high-dose tigecycline in combination regimen against CRE and CRAB [5,6,7]. Several previous observational studies demonstrated the potential of tigecycline to improve clinical response and decrease mortality in patients with nosocomial pneumonia. However, most of them are limited by a small sample size and significant heterogeneity in treatment strategies used [13,14,15,16].

Nosocomial pneumonia caused by CR-GNB is an emerging problem with limited antibiotic treatment options. Tigecycline has in vitro bacteriostatic activity against CR-GNB, but the clinical benefits of add-on tigecycline as part of a combination regimen CR-GNB-related nosocomial pneumonia remains uncertain. In the present study, we compared the clinical response rate and mortality rate between patients with HAP/VAP caused by CR-GNB who received add-on tigecycline treatment and those who did not. We hypothesized that add-on tigecycline as part of the combination regimen would provide clinical benefits. A subgroup analysis was also performed in order to determine whether the proposed synergistic benefits of add-on tigecycline treatment are dependent on other antibiotics used to treat nosocomial pneumonia caused by CR-GNB.

Methods

Patients and study setting

This was a multi-centre retrospective cohort study conducted at five referral medical centres in Taiwan between January 2016 and December 2016. The major aim of this study was to investigate the impact of antibiotics regimens on treatment outcomes of patients with HAP and VAP caused by CR-GNB. The study design and relevant prior analyses have been described [14, 17]. The eligibility criteria for inclusion in this study were as follows: (1) ICU-admitted patients diagnosed with HAP/VAP, which developed more than 48 h after admission; (2) positive cultures for CR-GNB, which is resistant to at least one of the carbapenems, were identified from respiratory specimens; and (3) received at least one key parenteral antibiotic considered for the treatment of pneumonia caused by CR-GNB, including colistin, sulbactam (ampicillin–sulbactam or cefoperazone–sulbactam), aminoglycoside, and carbapenem. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) age < 20 years old; (2) diagnosis of community-acquired pneumonia, healthcare associated pneumonia (HCAP), or concomitant lung cancer with obstructive pneumonitis; (3) CR-GNB showed resistance to tigecycline; (4) positive culture of Pseudomonas aeruginosa; (5) intravenous tigecycline with duration < 2 days and/or daily dosage < 100 mg.

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of all the participating hospitals (2018-03-001CC, 1-107-05-054, CE18100A, CMUH107-REC3-052, and KMUHIRB-E(I)-20180141). The need for informed consents was waived.

Data collection and disease severities definitions

Demographic characteristics and underlying comorbidities were retrospectively collected from complete electronic patient files from participating hospitals. Disease severity was evaluated by Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II score on ICU-admission day; Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) scores on ICU-admission day and the pneumonia index date; and presence of organ dysfunction [including septic shock (vasopressor use), renal failure (under dialysis), and respiratory failure (with mechanical ventilator and PF ratio < 200)] upon pneumonia diagnosis.

Pneumonia definitions

HAP refers to pneumonia occurring ≥ 48 h after hospital admission, and VAP refers to pneumonia developing ≥ 48 h after endotracheal intubation with an invasive mechanical ventilator. Causative organisms were defined as CR-GNB that were isolated from respiratory specimens, including sputum, endotracheal aspirates, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid with a concentration of ≥ 104 colony-forming units (CFU)/mL, and protected specimen brush with a concentration of ≥ 103 CFU/mL. For sputum and endotracheal aspirate, moderate-to-heavy growth by semi-quantitative method was considered to have HAP/VAP. The index culture study collection date was defined as the pneumonia index date. Definition of HCAP is provided in materials and methods of Additional file 1.

Microbiological tests and resistance determination

The results of susceptibility tests to carbapenems were determined according to the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) recommendations, 30th edition [18]. Carbapenem resistance was defined as resistance to imipenem or meropenem (imipenem or meropenem MIC ≥ 4 mg/L for Enterobacterales and MIC ≥ 8 mg/L for Acinetobacter spp.) Susceptibilities of tigecycline were determined according to the FDA standard (MIC ≤ 2 mg/L, sensitive; MIC = 4 mg/L, intermediate; MIC ≥ 8 mg/L, resistant) [19].

Treatment regimens and outcomes evaluation

Intravenous antibiotics that were used during the treatment course of nosocomial pneumonia with a duration ≥ 2 days were recorded. The daily dosage and treatment duration of intravenous tigecycline with a duration ≥ 2 days were recorded specifically for further analysis. Novel β-lactam/β-lactamase inhibitors, such as ceftazidime–avibactam and ceftolozane–tazobactam, were not available in Taiwan during the study period.

All the patients were followed until discharge or death. Treatment outcomes were compared between patients with and without add-on tigecycline in an antibiotic regimen. The outcomes evaluated in the present study included the clinical response rate, assessed on days 7, 14, and 28, and the all-cause mortality rate, assessed on days 14, 28, and upon discharge. Clinical responses were classified as “success” (resolution or substantial improvement of symptoms/signs of pneumonia, improvement or lack of progression of chest radiographic abnormalities, and no additional antibacterial therapy was required or was antibiotics free) and “failure” (no apparent response to therapy, persistent or worsening of symptoms/signs of pneumonia, persistent or progression of radiographic abnormalities that required additional antibiotic therapy, or death). Other outcomes of interest included ventilator weaning, new-onset dialysis, ICU stays, and hospital stays. All patients were followed up until death or hospital discharge. Details of clinical outcomes evaluation are provided in materials and methods of Additional file 1.

Time-window bias adjustment and propensity score matching

In considering the time-window bias related to delayed initiation of tigecycline, and possible differences in demographic characteristics and disease severity between patients with and without add-on tigecycline [20], we created a second cohort after time-window bias adjustment and propensity score (PS) matching. For time-window bias adjustment, patients who died within 3 days of the onset of pneumonia, or who were started on tigecycline more than 3 days of the pneumonia index date, were excluded. After time-window bias adjustment, a PS-matched cohort was built with a propensity score (PS) approach with 1:1 matching and calliper width of 0.2 applied to both patients with and without tigecycline treatment [21]. Propensity scores were created through a logistic regression as a function of age, sex, smoking, pathogens, pneumonia types, comorbidities, APACHE II scores (ICU admission), SOFA scores (pneumonia index date), albumin levels (pneumonia index date), presence of organs failure, and the key intravenous antibiotic used against CR-GNB.

Subgroup analysis of tigecycline-containing regimen

A subgroup analysis was performed to explore the differences of clinical efficacies of add-on tigecycline treatment when combined with various anti-CR-GNB agents, including colistin, carbapenem, and sulbactam. Patients were categorized as colistin group if intravenous colistin were included in the regimen, irrespective of the usage of other antibiotics. Patients were categorized as carbapenem groups or sulbactam group following the same rule. The treatment outcomes between patients with and without add-on tigecycline were compared in each subgroup of patients.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS version 25.0 software (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The clinical outcomes and mortality rates of patients with and without tigecycline add-on treatment were compared, using the Mann–Whitney U test for continuous numerical data, and the Pearson’s Chi-squared or Fisher’s exact tests for categorical data, respectively. Multiple imputation was used to compensate for with mean values was used for missing data. In a subgroup analysis, we further compared patients stratified according to the specific anti-CR-GNB antibiotic used. Kaplan–Meier survival curves were constructed to evaluate differences in all-cause mortality between the two groups. A stepwise Cox proportional hazard regression analysis was performed to identify the independent variables associated with mortality at day 28. Binary logistic regression analysis with forward stepwise selection was performed to determine the independent variables associated with clinical failure at day 28. All variables with a p-value < 0.1 at the univariate level were included in the multivariate model. All tests were two-tailed and a p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Patient characteristics

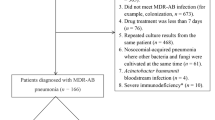

The present sample was selected from a group of 737 patients with nosocomial pneumonia caused by CR-GNB who were admitted to the ICU between January 2016 and December 2016. A flow diagram showing the numbers of cases and reasons for exclusion is shown in Fig. 1. In total, 395 cases fulfilled the inclusion criteria of whom 148 received add-on tigecycline treatment and 247 did not. As summarized in Table 1, nosocomial pneumonia was primarily caused by CRAB (81.3%), and 71.1% of cases were admitted to the medical ICU. The median APACHE II score upon ICU admission was 23 (18–27) and the median SOFA score on nosocomial pneumonia onset was 8 (5–10).

Patients who received add-on tigecycline treatment were less likely to receive sulbactam, had higher SOFA scores upon ICU admission, and had lower serum albumin levels on pneumonia index date. Patients with add-on tigecycline also showed a trend towards a higher proportion of nosocomial pneumonia caused by CRAB, and a trend towards more patients having received invasive ventilator support when nosocomial pneumonia occurred. A majority of the patients received tigecycline with daily dosage of 100 mg and the median duration of tigecycline treatment was 7 days (6–14 days). The age, sex, and underlying diseases were comparable between patients with and without add-on tigecycline.

PS-matched cohort after time-window bias adjustment

After time-window bias adjustment and PS matching (Fig. 1), we built a PS-matched cohort that included 102 patient pairs. As shown in Table 2, there were no significant differences in demographic characteristics, underlying comorbidities, disease severity, antibiotics used, or laboratory results between patients stratified according to add-on tigecycline treatment in the PS-matched cohort.

Add-on tigecycline was associated with better treatment outcomes

Treatment outcomes of patients with nosocomial pneumonia with and without tigecycline add-on treatment are shown in Table 3. In the original cohort, patients who received add-on tigecycline treatment had a trend towards a lower mortality rate on day 28 (27.7% vs. 36%, p = 0.088), and a lower clinical failure rate on day 14 (39.2% vs. 47.8%, p = 0.097) compared to patients without add-on tigecycline. The clinical failure rate on days 7 and 28, hospital mortality rate, and 28-day ventilator weaning rate were comparable between the two groups.

In the PS-matched cohort, patients who received add-on tigecycline treatment had significantly lower clinical failure rates on day 7 (37.3% vs. 52.0%, p = 0.035), 14 (39.2% vs. 57.8%, p = 0.008), and day 28 (46.1% vs. 62.7%, p = 0.017), and lower mortality rates on day 28 (28.4% vs. 52.9%, p < 0.001), and a lower hospital mortality rate (52.9% vs. 68.6%, p = 0.022).

Kaplan–Meier analyses of all-cause mortalities in the original cohort and PS-matched cohort are shown in Fig. 2. In the original cohort, there was no significant difference in 28-day mortality between patients who received add-on tigecycline treatment and those who did not (Fig. 2A). In the PS-matched cohort, patients who received add-on tigecycline treatment had a lower 28-day mortality risk compared to patients without add-on tigecycline (Fig. 2B). The curves separated early after pneumonia onset.

Independent factors associated with treatment outcomes

Univariate and multivariate analyses were performed to identify independent clinical factors associated with all-cause mortality and clinical failure rates at day 28. In the original cohort, independent factors associated with all-cause mortality on day 28 included body mass index (BMI) (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR] 0.94, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.90–0.98), SOFA scores on the pneumonia index date (aHR 1.17, 95% CI 1.11–1.24), and tigecycline treatment (aHR 0.69, 95% CI 0.47–0.99) (Table 4). Independent factors associated with clinical failure on day 28 included BMI (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 0.92, 95% CI 0.88–0.97), pneumonia caused by CRAB (aOR 2.21, 95% CI 1.27–3.87), and SOFA scores on the pneumonia index date (aOR 1.20, 95% CI 1.11–1.29). In the PS-matched cohort, independent factors associated with all-cause mortality on day 28 included BMI (aHR 0.93, 95% CI 0.88–0.99), SOFA scores on the pneumonia index date (aHR 1.12, 95% CI 1.06–1.19), and tigecycline treatment (aHR 0.47, 95% CI 0.30–0.74) (Table 5). Independent factors associated with clinical failure on day 28 included BMI (aHR 0.90, 95% CI 0.83–0.97), SOFA scores on the pneumonia index date (aOR 1.19, 95% CI 1.09–1.31), and tigecycline treatment (aOR 0.52, 95% CI 0.28–0.95).

Subgroup analysis

We performed a subgroup analysis to identify the clinical effects of add-on tigecycline treatment when combined with colistin, carbapenem, and sulbactam, respectively. As shown in Fig. 3A, add-on tigecycline treatment was significantly associated with a lower clinical failure rate on day 28 in patients treated with colistin, but not in patients treated with carbapenem and sulbactam. In a Kaplan–Meier survival curve analysis, patients who received add-on tigecycline treatment had a lower mortality rate in the subgroup treated with colistin (log rank p value 0.005) or carbapenem (log rank p value 0.007), but not with sulbactam (Fig. 3B).

Considering that a major portion of the enrolled patients had HAP/VAP caused by CRAB, we made a subgroup analysis in patients infected by CRAB. As shown in Additional file 1: Table S1, in original cohort, patients with add-on tigecycline had lower day 14 clinical failure rate and a trend of lower day 28 mortality rate. After time-window bias adjustment and PS matching, lower clinical failure rate on day 14, day 28, and lower mortality on day 28 were noted in patients with add-on tigecycline.

Discussion

Nosocomial pneumonia caused by CR-GNB, particularly CRAB, CRE, and CR-pseudomonas, continues to be a growing concern, especially in critically ill patients with ICU admission. When compared with non-CR-GNB pathogens, CR-GNB can significantly increase the risk of mortality in patients with nosocomial infection. Novel β-lactam/β-lactamase inhibitors are the treatment of choice for infection caused by CRE [6, 7], and monotherapy is generally recommended. When novel agents are not available or when CRE isolates are resistant to novel agents, combination of old drugs is suggested [6]. CRAB isolates are generally resistant to novel β-lactam/β-lactamase inhibitors. For moderate to severe infection caused by CRAB, combination of old antibiotics, including sulbactam, polymyxin, tigecycline, minocycline, and aminoglycoside, should be used [5, 6]. When tigecycline is included in a combination regimen against CRE or CRAB, high-dose tigecycline (daily dose 200 mg) is recommended, although the evidence level is low [5,6,7, 22, 23]

Although tigecycline is recommended as an antibiotic against CRE and CRAB, most evidences came from patients with intra-abdominal infection [24, 25]. The role of tigecycline in nosocomial pneumonia remains controversial. The latest HAP/VAP guideline actually recommended against the use of tigecycline in the treatment of HAP/VAP [4]. Potential complications related to tigecycline, including coagulopathy and pancreatitis, also limited its usage in critically ill patients [26, 27]. A phase III randomized controlled trial reported that tigecycline monotherapy was associated with a higher mortality rate compared with imipenem/cilastatin in patients with HAP [12]. On the other hand, a prospective observational study reported a significantly lower mortality rate for tigecycline/imipenem combination therapy in patients with VAP caused by CRAB, when compared to sulbactam/imipenem combination therapy [28]. Several retrospective observational studies or meta-analyses reported improved responses of tigecycline-containing regimens in patients with nosocomial pneumonia [13, 15, 16, 29], while some studies reported worse outcomes [30, 31]. Some differences in the patient sample between our sample and prior ones bears mentioning. In the present study, all the patients had HAP/VAP that occurred during ICU admission, with a median APACHE II score of 23 and a median SOFA score of 8, which represent a population with a high disease severity. The patients in this study had HAP/VAP caused by tigecycline-susceptible pathogens, and received at least one key anti-CR-GNB agent. Considering the differences in demographic characteristics and disease severities between patients with and without tigecycline, and confounding for survival time bias, we built a PS-matched cohort with survival time bias adjustment. We found that patients with tigecycline in a combination regimen had lower clinical failure rate and all-cause mortality rate on day 28 in PS-matched cohort. In multivariate analysis of PS-matched cohort, we also identified add-on tigecycline as an independent factor associated with lower clinical failure and mortality on day 28. Our findings suggest that add-on tigecycline to a regimen that contains a key anti-CR-GNB antibiotic can further improve the clinical outcomes of critically ill patients with HAP/VAP caused by tigecycline-susceptible CR-GNB.

Our subgroup analysis showed that the clinical benefits of add-on tigecycline were most significant when tigecycline was included as part of a colistin-based regimen, although non-significant trends in favour of a synergistic effect were also evident for carbapenem-based or sulbactam-based regimens. Tigecycline has synergistic effects with colistin, since colistin-induced disruption of the bacterial membrane may facilitate the uptake of tigecycline into the cytoplasm [32]. In vitro synergistic effects between tigecycline and sulbactam or carbapenem have also been reported [33, 34]. The superior treatment responses of tigecycline when used in a colistin-based regimen deserve further validation.

This study had several limitations. First, significant differences in disease severity existed between patients who received add-on tigecycline treatment and those who did not. To address this issue, we performed time-window bias adjustment and PS-matched analysis, and confirmed the clinical benefits of add-on tigecycline in the PS-matched cohort. Second, novel β-lactam/β-lactamase inhibitors were not available during the study period. The synergism between tigecycline and novel agents was therefore not explored. Third, only few of the included patients received high-dose tigecycline. Therefore, the dosage issue of tigecycline could not be further investigated. The benefits of add-on tigecycline in the present study may also be underestimated. Information regarding the adverse events related to tigecycline was not collected and was not reported in the present study. Finally, more than 80% of the enrolled patients had nosocomial pneumonia caused by CRAB. Therefore, the implication of our findings relevant to CRE should be interpreted with caution.

Conclusions

In this retrospective observational study that included ICU-admitted patients with nosocomial pneumonia caused by CR-GNB, mostly CRAB, tigecycline as part of a combination treatment regimen was associated with lower clinical failure and all-cause mortality rates. Considering the worse treatment outcomes in patients with nosocomial pneumonia, and limited antibiotic choices against CR-GNB, tigecycline could be included as part of a combination antibiotics regimen if microbiological susceptibility is demonstrated. Further prospective controlled trials are warranted to verify our findings and clarify the optimal combination regimen with tigecycline to improve outcomes in eligible patients.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Vo-Pham-Minh T, Duong-Thi-Thanh V, Nguyen T, Phan-Tran-Xuan Q, Phan-Thi H, Bui-Anh T, et al. The impact of risk factors on treatment outcomes of nosocomial pneumonia due to Gram-negative bacteria in the intensive care unit. Pulm Ther. 2021;7(2):563–74.

Kalanuria AA, Ziai W, Mirski M. Ventilator-associated pneumonia in the ICU. Crit Care. 2014;18(2):208.

Watkins RR, Van Duin D. Current trends in the treatment of pneumonia due to multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacteria. F1000Res. 2019. https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.16517.2.

Kalil AC, Metersky ML, Klompas M, Muscedere J, Sweeney DA, Palmer LB, et al. Management of adults with hospital-acquired and ventilator-associated pneumonia: 2016 clinical practice guidelines by the infectious diseases society of America and the American Thoracic Society. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63(5):e61–111.

Tamma PD, Aitken SL, Bonomo RA, Mathers AJ, van Duin D, Clancy CJ. Infectious Diseases Society of America guidance on the treatment of AmpC beta-lactamase-producing Enterobacterales, carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii, and Stenotrophomonas maltophilia infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2022;74(12):2089–114.

Paul M, Carrara E, Retamar P, Tangden T, Bitterman R, Bonomo RA, et al. European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (ESCMID) guidelines for the treatment of infections caused by multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacilli (endorsed by European society of intensive care medicine). Clin Microbiol Infect. 2022;28(4):521–47.

Tamma PD, Aitken SL, Bonomo RA, Mathers AJ, van Duin D, Clancy CJ. Infectious Diseases Society of America guidance on the treatment of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase producing Enterobacterales (ESBL-E), carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales (CRE), and Pseudomonas aeruginosa with difficult-to-treat resistance (DTR-P. aeruginosa). Clin Infect Dis. 2021;72(7):e169–83.

Wilson WR, Kline EG, Jones CE, Morder KT, Mettus RT, Doi Y, et al. Effects of KPC variant and porin genotype on the in vitro activity of meropenem-vaborbactam against carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2019;63(3):e02048-18.

Zhanel GG, Karlowsky JA, Rubinstein E, Hoban DJ. Tigecycline: a novel glycylcycline antibiotic. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2006;4(1):9–25.

Kehl SC, Dowzicky MJ. Global assessment of antimicrobial susceptibility among Gram-negative organisms collected from pediatric patients between 2004 and 2012: results from the tigecycline evaluation and surveillance trial. J Clin Microbiol. 2015;53(4):1286–93.

Cooper TW, Pass SE, Brouse SD, Hall RG 2nd. Can pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic principles be applied to the treatment of multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter? Ann Pharmacother. 2011;45(2):229–40.

Freire AT, Melnyk V, Kim MJ, Datsenko O, Dzyublik O, Glumcher F, et al. Comparison of tigecycline with imipenem/cilastatin for the treatment of hospital-acquired pneumonia. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2010;68(2):140–51.

Park JM, Yang KS, Chung YS, Lee KB, Kim JY, Kim SB, et al. Clinical outcomes and safety of meropenem-colistin versus meropenem-tigecycline in patients with carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii pneumonia. Antibiotics. 2021;10(8):903.

Wang SH, Yang KY, Sheu CC, Chen WC, Chan MC, Feng JY, et al. Efficacies of colistin-carbapenem versus colistin-tigecycline in critically ill patients with CR-GNB-associated pneumonia: a multicenter observational study. Antibiotics. 2021;10(9):1081.

Liu B, Li S, Li HT, Wang X, Tan HY, Liu S, et al. Outcomes and prognostic factors of tigecycline treatment for hospital-acquired pneumonia involving multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. J Int Med Res. 2020;48(4):300060520910917.

Jean SS, Hsieh TC, Lee WS, Hsueh PR, Hsu CW, Lam C. Treatment outcomes of patients with non-bacteremic pneumonia caused by extensively drug-resistant Acinetobacter calcoaceticus–Acinetobacter baumannii complex isolates: is there any benefit of adding tigecycline to aerosolized colistimethate sodium? Medicine. 2018;97(39): e12278.

Feng JY, Peng CK, Sheu CC, Lin YC, Chan MC, Wang SH, et al. Efficacy of adjunctive nebulized colistin in critically ill patients with nosocomial carbapenem-resistant Gram-negative bacterial pneumonia: a multi-centre observational study. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2021;27(10):1465–73.

Weistein MP, Lewis II JS, Bobechik AM, Campeau S, Cullen SK, Fallas MF, Gold H, Humphries RM, Kirn TJ. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing: twenty-ninth informational supplement, 30th edition. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 2020. https://clsi.org/media/3481/m100ed30_samplepdf.

Sader HS, Farrell DJ, Jones RN. Tigecycline activity tested against multidrug-resistant Enterobacteriaceae and Acinetobacter spp. isolated in US medical centers (2005–2009). Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2011;69(2):223–7.

Suissa S, Dell’aniello S, Vahey S, Renoux C. Time-window bias in case-control studies: statins and lung cancer. Epidemiology. 2011;22(2):228–31.

Austin PC. Optimal caliper widths for propensity-score matching when estimating differences in means and differences in proportions in observational studies. Pharm Stat. 2011;10(2):150–61.

De Pascale G, Montini L, Pennisi M, Bernini V, Maviglia R, Bello G, et al. High dose tigecycline in critically ill patients with severe infections due to multidrug-resistant bacteria. Crit Care. 2014;18(3):R90.

De Pascale G, Lisi L, Ciotti GMP, Vallecoccia MS, Cutuli SL, Cascarano L, et al. Pharmacokinetics of high-dose tigecycline in critically ill patients with severe infections. Ann Intensive Care. 2020;10(1):94.

Eckmann C, Montravers P, Bassetti M, Bodmann KF, Heizmann WR, Sanchez Garcia M, et al. Efficacy of tigecycline for the treatment of complicated intra-abdominal infections in real-life clinical practice from five European observational studies. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2013;68(Suppl 2):ii25–35.

Babinchak T, Ellis-Grosse E, Dartois N, Rose GM, Loh E, Tigecycline 301 Study G, et al. The efficacy and safety of tigecycline for the treatment of complicated intra-abdominal infections: analysis of pooled clinical trial data. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41(Suppl 5):S354–67.

Guo M, Liang J, Li D, Zhao Y, Xu W, Wang L, et al. Coagulation dysfunction events associated with tigecycline: a real-world study from FDA adverse event reporting system (FAERS) database. Thromb J. 2022;20(1):12.

Davido B, Shourick J, Makhloufi S, Dinh A, Salomon J. True incidence of tigecycline-induced pancreatitis: how many cases are we missing? J Antimicrob Chemother. 2016;71(10):2994–5.

Jean SS, Hsieh TC, Hsu CW, Lee WS, Bai KJ, Lam C. Comparison of the clinical efficacy between tigecycline plus extended-infusion imipenem and sulbactam plus imipenem against ventilator-associated pneumonia with pneumonic extensively drug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii bacteremia, and correlation of clinical efficacy with in vitro synergy tests. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2016;49(6):924–33.

Mei H, Yang T, Wang J, Wang R, Cai Y. Efficacy and safety of tigecycline in treatment of pneumonia caused by MDR Acinetobacter baumannii: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2019;74(12):3423–31.

Liang CA, Lin YC, Lu PL, Chen HC, Chang HL, Sheu CC. Antibiotic strategies and clinical outcomes in critically ill patients with pneumonia caused by carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2018;24(8):908-e1-908-e7.

Ni W, Han Y, Zhao J, Wei C, Cui J, Wang R, et al. Tigecycline treatment experience against multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii infections: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2016;47(2):107–16.

Abdul-Mutakabbir JC, Yim J, Nguyen L, Maassen PT, Stamper K, Shiekh Z, et al. In vitro synergy of colistin in combination with meropenem or tigecycline against carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Antibiotics. 2021;10(7):880.

Bae S, Kim MC, Park SJ, Kim HS, Sung H, Kim MN, et al. In vitro synergistic activity of antimicrobial agents in combination against clinical isolates of colistin-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2016;60(11):6774–9.

Temocin F, Erdinc FS, Tulek N, Demirelli M, Ertem G, Kinikli S, et al. Synergistic effects of sulbactam in multi-drug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Braz J Microbiol. 2015;46(4):1119–24.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported, in part, by research grants from Ministry of Science and Technology (Taiwan) (MOST 109-2314-B-010-051-MY3, 111-2314-B-075-058), Taipei Veterans General Hospital (V112C-068, V112C-181). Additionally, this work was financially supported by the “Cancer Progression Research Center, National Yang Ming Chiao Tung University” from The Featured Areas Research Center Program within the framework of the Higher Education Sprout Project by the Ministry of Education (MOE) in Taiwan (111W31101, 111W31206).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

Conceptualization: J-YF, C-KP, C-CS, Y-CL, M-CC, K-YY. Data curation: J-YF, S-HW, C-MC, Y-CS, Z-RZ. Formal analysis: J-YF, K-YY. Methodology: J-YF, C-KP, C-CS, Y-CL, M-CC, K-YY, Y-TL. Project administration: C-KP, C-CS, Y-CL, M-CC, K-YY. Supervision: C-KP, C-CS, Y-CL, M-CC, K-YY. Validation: C-KP, C-CS, Y-CL, M-CC, K-YY. Writing—original draft: J-YF, K-YY. Writing—review and editing: J-YF, C-KP, S-HW, C-CS, C-MC, Y-CL, Y-CS, M-CC, Z-RZ, K-YY. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of all the participating hospitals (2018-03-001CC, 1-107-05-054, CE18100A, CMUH107-REC3-052, and KMUHIRB-E(I)-20180141). Individual patient consent was not required for a study of this type.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declared that no competing interests exist.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

Materials andmethods. Table S1. Treatment outcomes of Propensity Score-matched ICU patients with nosocomial pneumonia caused by CRAB treated with and without add-on tigecycline in combination regimena.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, KY., Peng, CK., Sheu, CC. et al. Clinical effectiveness of tigecycline in combination therapy against nosocomial pneumonia caused by CR-GNB in intensive care units: a retrospective multi-centre observational study. j intensive care 11, 1 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40560-022-00647-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40560-022-00647-y